FOREWORD

The life of Theodore Roosevelt (1858–1919) coincided with the most colorful period of American journalism. Between the Gilded Age of illustrated magazines and the advent of the hard-boiled city rooms of The Front Page was the era of colored political-cartoon magazines, yellow journalism, and the muckrakers. The cartoons in BULLY! are collected from those vibrant but now scarce and nearly forgotten pages. Cartoonists and reporters had no better subject during those years than Theodore Roosevelt—not even frontier expansion, wars, and innovations such as railroads, telephones, motion pictures, automobiles, and flying machines would compete.

America came of age during this era, with a growing leisure class that was able to indulge an appetite for politics, current affairs, and the arts in periodicals. Technology freed cartoonists from old-fashioned chalk-plates and wood-engravings, allowing them to reproduce pen drawings with all the glorious detail they could invest. Cartoonists captured the issues of the day—war and peace, economic crises, the growing divide between rich and poor—bringing them more poignantly to the attention of readers to whom the editorial cartoon was truly worth a thousand words.

Theodore Roosevelt was the perfect subject for the cartoonists’ art. One is tempted to say that if TR, in all his distinctive glory, had not come along, American culture would have had to invent him. Presidents were boring before Theodore Roosevelt, and boring after him; life, as many said after he died, seemed emptier without him.

Cartoonists did not create Theodore Roosevelt, however—not by any means. His life was a series of memorable phases: writing dozens of books and hundreds of magazine articles; living the life of a cowboy; fighting heroically on the battlefield; devoting himself to innumerable interests and physical pastimes; enjoying a vaunted circle of friends. All of this would make up TR's biography, even without the cartoonists.

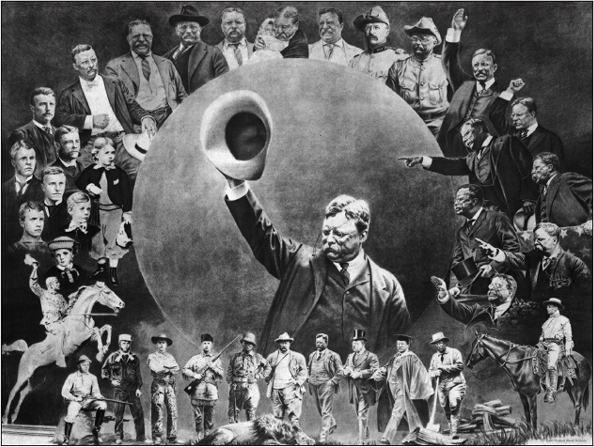

Still, cartoonists of his day best conveyed his traits, keeping them alive for posterity. Press photography was still coming into its own during the period in which cartoonists drew the likenesses we know today. Movies and newsreels were new, but cartoonists told us how Roosevelt walked and ran and rode and gestured and laughed.

Theodore Roosevelt was perhaps the most caricatured president—if not the most caricatured American—in history. Here is the raw material cartoonists had to work with: TR was of average height, between 5'8" and 5'10". People noticed that he had rather small ears. He had sandy hair and was often “brown as a nut” from outdoor activities. An obsessive exerciser, Roosevelt was barrel-chested with a thick, muscular neck. He was comfortable, as a patrician, in silk vests, top hats, and pince-nez spectacles with a cord. But he fit just as well into riding clothes, boots, and wire-rimmed glasses. It is probable that he frequently displayed an assortment of cuts, blisters, and bruises; such was the occupational hazard of an inveterate hunter, hiker, sportsman, boxer, not to mention someone who romped crazily with his children for an hour every afternoon.

He spoke with great animation, chopping off his words as if each were a separate bite of meat. He clicked his teeth between words or sentences and elongated his “s” sounds. He spoke in a rich baritone flavored with an East Coast aristocrat's affected “Harvard accent.” But when emphasizing a point, or aiming for humor, he lapsed into a comical falsetto. TR laughed frequently, and likely had the best sense of humor of any president other than Lincoln. His military aide, Major Archie Butt, once confided in a letter to a relative that at a pompous funeral, he could scarcely keep a straight face through Roosevelt's whispered stream of sarcasms and humorous commentary. TR also relished humor at his own expense, one of many refutations against those who say he possessed a large ego.

He did not dislike many people, but he surely disliked things some people did, or things they stood for. When he was someone's opponent, they knew it. He could be withering in print to such folks, and no less to their faces.

He was a proponent of many “new” things in a new age; but in terms of morality, manners, and traditions, he was a Victorian—almost a prude, and blue-nosed. He favored women's suffrage before most politicians (and before his wife did), but maintained, as a traditionalist, that “equality of rights should not be confused with equality of function” in society. He hated to be called “Teddy,” and said that anyone who used the nickname did not know him and did not respect his wishes. We respect his wishes in this biography.

For other descriptions of the physical Roosevelt—more of what the cartoonists had to work with—I present some passages from William Bayard Hale's series of articles for The New York Times in 1908. For “A Week in the White House,” the writer was allowed an unfettered presence in all meetings and activities, and his observations provide a thorough description of the man.

Imagine [him] at the desk sometimes, on the divan sometimes, sometimes in a chair in the farthest corner of the Cabinet room, more often on his feet—it may be anywhere within the four walls—the muscular, massive figure of Mr. Roosevelt. You know his features—the close-clipped brachycephalous head, close-clipped mustache, pince-nez, square and terribly rigid jaw.

Hair and moustache indeterminate in color; eyes a clear blue; cheeks and neck ruddy. He is in a frock-coat, a low collar with a four-in-hand, a light waistcoat, and grey striped trousers—not that you would ever notice all that unless you pulled yourself away from his face and looked with deliberate purpose. Remember that he is almost constantly in action, speaking earnestly and with great animation; that he gestures freely, and that his whole face is always in play. For he talks with his whole being—mouth, eyes, forehead, cheeks, and neck all taking their mobile parts.

The President is in the pink of condition today…. Look at him as he stands and you will see that he is rigid as a soldier on parade. His chin is in, his chest out. The line from the back of his head falls straight as a plumb-line to his heels. Never for a moment, while he is on his feet, does that line so much as waver, that neck unbend. It is a pillar of steel. Remember that steel pillar. Remember it when he laughs, as he will do a hundred times a day—heartily, freely, like an irresponsible school-boy on a lark, his face flushing ruddier, his eyes nearly closed, his utterance choked with mirth, and speech abandoned or become a weird falsetto. For the President is a joker, and (what many jokers are not) a humorist. He is always looking for fun—and always finding it. He likes it rather more than he does a fight—but that's fun too. You have to remember, then, two things to see the picture: a room filled with constant good humor, breaking literally every five minutes into a roar of laughter—and a neck of steel.

Not that the President always stands at attention. He doubles up when he laughs, sometimes. Sometimes—though only when a visitor whom he knows well is alone with him—he puts his foot on a chair. When he sits, however, he is very much at ease—half the time with one leg curled up on the divan or maybe on the Cabinet table top. And, curiously, when the President sits on one foot, his visitor is likely to do the same, even if, like Mr. Justice Harlan or Mr. J. J. Hill, he has to take hold of the foot and pull it up.…

Remember that Mr. Roosevelt never speaks a word in the ordinary conversational tone…. His face energized from the base of the neck to the roots of the hair, his arms usually gesticulating, his words bursting forth like projectiles, his whole being radiating force. He does not speak fast, always pausing before an emphatic word, and letting it out with the spring of accumulated energy behind it. The President doesn't allow his witticisms to pass without enjoying them. He always stops—indeed, he has to stop till the convulsion of merriment is over and he can regain his voice.

The President enters into a subject which arouses him. He bursts out against his detractors. His arms begin to pump. His finger rises in the air. He beats one palm with the other fist. “They have no conception of what I'm driving at, absolutely None. It Passes Belief—the capacity of the human mind to resist intelligence. Some people Won't learn, Won't think, Won't know. The amount of—stupid Perversity that lingers in the heads of some men is a miracle.”

The President's good-humor and candor have not been sufficiently appreciated. It is good to have a President with a laugh like Mr. Roosevelt's. That laugh is working a good deal too; hardly does half an hour, seldom do five minutes go by without a joyful cachinnation from the Presidential throat…. The fun engulfs his whole face; his eyes close, and speech expires in a silent gasp of joy.

He is, first of all, a physical marvel. He radiates energy as the sun radiates light and heat…. It is not merely remarkable, it is a simple miracle, that this man can keep up day after day—it is a sufficient miracle that he can exhibit for one day—the power which emanates from him like energy from a dynamo…. He radiates from morning until night, and he is nevertheless always radiant.

Never does the President appear to meet a personality than which he is not the stronger; an idea to which he is a stranger; a situation which disconcerts him. He is always master. He takes what he pleases, gives what he likes, and does his will upon all alike. Mr. Roosevelt never tires; the flow of his power does not fluctuate. There is never weariness on his brow nor, apparently, languor in his heart…. The President ends the day as fresh as he began it. He is a man of really phenomenal physical power, a fountain of perennial energy, a dynamic marvel.

The President is able to concentrate his entire attention on the subject in hand, whether it be for an hour or for thirty seconds, and then instantly to transfer it, still entirely concentrated, to another subject…. He flies from an affair of state to a hunting reminiscence; from that to an abstract ethical question; then to a literary or a historical subject; he settles a point in an army reorganization plan; the next second he is talking earnestly to a visitor on the Lake Superior whitefish, the taste of its flesh and the articulation of its skeleton as compared with the shad; in another second or two he is urging the necessity of arming for the preservation of peace, and quoting Erasmus; then he takes up the case of a suspected violation of the Sherman law, and is at the heart of it in a minute; then he listens to the tale of a Southern politician and gives him rapid instruction; turns to the intricacies of the Venezuela imbroglio, with the mass of details of a long story which everybody else has forgotten at his finger tips; stops a moment to tell a naval aide the depth and capacity of the harbor of Auckland; is instantly intent on the matter of his great and good friend of the Caribbean; takes up a few candidacies for appointments, one by one; recalls with great gusto the story of an adventure on horseback; greets a delegation; discusses with a Cabinet secretary a recommendation he is thinking of sending to Congress. All this within half an hour. Each subject gets full attention when it is up; there is never any hurrying away from it, but there is no loitering over it.

These assessments came, by the way, from someone who was not a hero-worshiper. Hale was a Democrat, writing for a Democrat newspaper; he confessed to be out of sympathy with Roosevelt's policies, and within four years he would be writing Woodrow Wilson's campaign biography.

You will see in this book that countless cartoonists tried to capture the coruscating nature of this man Roosevelt. As cartoonists with multiple panels to fill, they perhaps had an easier job than Hale. In any event, it was more fun. “Slow news days” were solved in the city rooms of American newspapers: cartoonists could draw what TR did, or would do, or might do. He was the cartoonists' best friend.

Cartoons and comic strips—not just editorial and political cartoons—tell us about more than public affairs of the day. They describe manners and morals, fads and fancies. Cartoons tell us how people dressed, what they liked or avoided, what angered them, and what made them laugh. They truly are snapshots in a beloved American family album.

You will meet here the great cartoonists: from Nast and the Kepplers (father and son) and the Gillam brothers, in the magazines; to Opper and Davenport and McCutcheon, in the newspapers; from forgotten geniuses like Charles Green Bush and Joseph Donahey, to Winsor McCay of Little Nemo fame, and Pulitzer Prize-winners like Ding Darling. The cartoons herein were culled from famous magazines Puck, Judge, and Life, and from major newspapers of the turn of the last century, including New York's Journal, World, and Herald. Printed in the millions, they are almost impossible to find today. You will discover forgotten cartoonists from obscure publications…and, I hope, you will revel as I have in the discovery of prescient commentary cleverly drawn and presented in great numbers and variety. With such a rich lode to mine (for I have been fortunate to assemble what is arguably the nation's largest archive of such source-material), I endeavor in BULLY! to bring out the work of more obscure artists over the familiar. Thus, if textbooks have given us a Keppler or a Davenport on a certain topic, and if a “forgotten” cartoonist has made an equally trenchant observation on the same event, I introduce that cartoonist to posterity.

Through the cartoons reproduced in this book, you will experience what America was like 100 years ago. Mostly, though, I want you to meet Theodore Roosevelt in a new way. These illustrations are not just cartoons—they unveil for us the caricatured Roosevelt, revealing an aspect of the man's character that has been little explored. There has not yet been a biography of TR's entire life relying on colorful cartoons as guides. In so crafting BULLY!, I have aimed for a comprehensive but not exhaustive biography. The greatest value to all readers, whether you are a devotee of American history in general, or a member of the large, loyal, and increasing corps of TR fans specifically, will be the wealth of pictorial commentary and satire herein. Cartoonists had their own “bully pulpits,” right at their ink-stained drawing tables, and we are all the richer from their legacy.