Eastern Europe and much of central and western Europe offered vast spaces for breeding and raising livestock. During the Early Modern era demographic pressures were not yet intense enough to force the conversion of grazing lands into wheat fields or reduce the extent of pasturelands below the threshold of productivity. We must remember that a decrease in the area intended for pasture is not directly proportional to a reduction in the number of animals raised. If less than an appropriate given area is devoted to pasture, raising livestock commercially is no longer economically sustainable (except for domestic husbandry, which is hardly the same thing).

In Italy, where the plains were dotted with myriad towns from which issued a strong demand for grain, farmers drove their herds to graze on summer pastureland high in the mountains (transhumance). This alternative seasonal possibility of feeding flocks of sheep and herds of cows meant that meat, especially beef, was available nearby in all of Europe and as far east as the Ottoman Empire.

As for beef itself, we need to take into account the strong demand for leather driven by the Florentine market: with leather one produced shoes, boots, saddles and harnesses for horses and mules, suits, belts, purses, and an endless array of objects that today would be made of plastic, rubber, and so forth. Halfway through the fifteenth century the Venetian Giacomo Badoer shipped thousands of preserved ox hides from Constantinople to Venice. In the middle of the seventeenth century Baccio Durazzo, originally from Genoa, bought and shipped thousands of skins from Smyrna. These two examples should suffice as illustration. All these beef cattle, whose skins were bought and sold, were neither buried nor burned; instead they provided meat to the entire Anatolian peninsula, either as fresh meat or as dried meat meant to supply the army. In this example the demand for leather was the dominant demand, as exemplified by the ample importation of leather from America and later by the settlement and creation of the huge ranches of Argentina. Export and import of meat itself had to await the launching of refrigerated ships.

Along the Danube as far as Pannonia and Germany there arose numerous livestock farms intended to feed central Europe. It was precisely there that a huge distribution center was created from which Venice and Genoa but especially Austria, Hungary, and Poland drew supplies. From Germany, pickled beef tongues came into Italy, where it seems they were much appreciated. Of course, Germany is the homeland of beef conserved in the form of cooked sausages (Würstel). At a time when false teeth were not yet available, ground, flavored meat had a practical as well as gastronomic appeal.

Raising livestock was also important in Italy. Differences in price allowed one to distinguish those areas where the product was superior (Moncalvo d’Asti, for example, was the market favored by the Genoese). It would seem that we are dealing here with a kind of biotechnology intended to develop quality meat products while also ensuring that the towns had a steady supply for the shoemakers as well.

In addition to importing cattle herds from the East, Germany, France, England, and Denmark autonomously produced excellent meats. And of course cattle breeding and raising livestock were important on the Iberian Peninsula and in the rest of Europe.

I mentioned leather at the beginning of this chapter to make the point that from a cow or an ox one derived more than meat and that this fact allowed the distribution or spread of costs and especially of revenue. At times leather might be more in demand than meat, so one slaughtered a cow more for its skin than for anything else. Cattle purchased at the breeding site were brought for slaughter to various towns. Except for the wages of the cowherds there were no other transportation costs: meat travels on its own legs. Livestock was therefore less expensive to market than other products that had to be transported via inaccessible roads on muleback.

Near the large cattle herds were found the peasants’ modest livestock: two or three cows to give milk, produce calves, and help in tilling the fields. There were also calves raised with special care on private property, that is, by the owners of the land, in order to obtain the most desirable meat. In the Piedmont, one said that this home-raised veal was à la façon du particulier (today we would say “customized”). The veal calves were sold to the city butchers and then added to the yearly list of provisions inventoried by the authorities of the Annone. Often the butchers negotiated partnership contracts with the small farmer in order to have veal calves at their disposal even when the larger cattle markets were in difficulty. Nor was there a shortage of rural entrepreneurs who hoarded cows on the farms and estates near the town.

Oxen were used to work in the fields and to pull carts. When the last labors of fall had been completed (harrowing, for example), the aging animal was shut in its pen and fed on cereals, hay, and other grasses—in short, fattened for sale and ultimately for slaughter. At Christmas, it yielded a big boiled meat dish and the broth for cooking pasta, usually thick macaroni. This was not a tradition but rather a habit born from the desire to use the ox for fieldwork up to the very last.

Meat from the ox, the cow, and the steer was rather tough and chewy, if tastier. Veal was the preferred meat, a food, however, for the more prosperous classes, costing about twice the price of steer.

Jean-Louis Flandrin writes that until the end of the Middle Ages the French aristocracy scorned beef and preferred other meats, such as poultry and above all game. In the Early Modern era, however, consumption of butchered meat became valued once again. In the Mediterranean, veal maintained its rank and, along with beef, was purchased throughout the sixteenth, seventeenth, and eighteenth centuries. Veal was meant for the master’s table, beef for the servants.

Servants enjoyed beef five days a week, and a pound of beef per person was served thrice weekly in hospitals. In Genoa a pound of beef cost two soldi in the sixteenth century and little more in succeeding centuries. In the same city the lowest salary, that of a boy helper or a cleaning woman, was six soldi a day, whereas an adult male could earn from ten to fifteen soldi daily, according to his occupation. A cook earned from two to four lire per day, and a cook’s assistant or sous-chef one or two lire (a lira was worth twenty soldi). To sum up, with the minimum salary one could purchase three pounds of boneless beef, a quantity of protein sufficient for a whole week. Orazio Cancila confirms the same price range and general availability of butchered meat in Palermo.

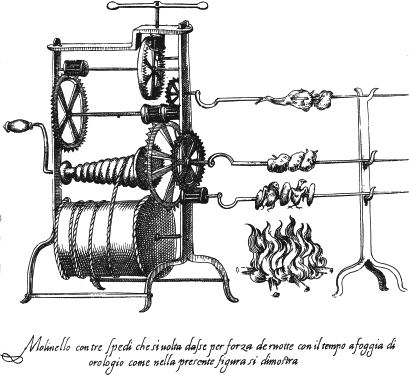

FIGURE 17

Meats on a spit, engraving from Bartolomeo Scappi, Opera dell’arte del cucinare (Works from the art of cooking) (Venice, 1570).

Beef was therefore not a luxury product but one of the most accessible foods, consumed in quantities that today would seem excessive. Given that meat cost relatively little, butchers thought up pricing it on a sliding scale according to the cut; thus the custom arose of making fillets more expensive than haunches and saving the tripe for the less wealthy. Documents from eighteenth-century Paris confirm this. The ancient pride of the Germanic peoples had become a daily ration with little prestige, so the nobles had to turn their attention to game, fish, and other meats more expensive than beef.

England and Spain nourished within their respective confines countless sheep from which they derived wool, rams’ skins, and parchment. The tails of Persian and Turkish sheep yielded a fat that replaced lard (forbidden by Islam). From the fat tails of English sheep there came a delicacy still appreciated today. Thomas More wrote that in the British Isles sheep devoured men, meaning that land was above all devoted to pasture. Whether in England or Spain, however, men certainly fed on mutton and lamb, not to mention the sheep themselves, which, when slaughtered, ended up cooked in various ways (boiled, for example). Flocks were so numerous it would not astonish me if the basic food of these countries were above all mutton, a meat both more tender and more flavorful than beef. Especially tasty was lamb, the prescribed meat for Hebrews as well as for Christians and Muslims in celebrating Easter or spring festivals. Since lamb was an ordinary food, the English lords preferred beef. The guard of the Tower of London is called a Beefeater, and enormous roast beefs tower over their banquets.

In European cities lamb cost the same as other meats and sometimes a bit less. Shoulder of lamb was sold on the bone, and the yield in edible matter was therefore quite a bit less than that of a slice of beef. The same is true for the haunch, not to mention the rest of the cow. Lamb and goat were never alternative meats to beef if by alternative one means greater convenience. These meats were tenderer, tastier, and sometimes more expensive, especially in northern Italy and in France, at least in Paris, where urban crowds and cultivation had expropriated large areas of grazing land from big herds. Recall too that ever since the Middle Ages Italy was a big importer of lamb’s wool and early on replaced parchment with paper.

The greater part of my documentation derives from the archives of cities where herds and flocks were brought for slaughter and meat distributed through a network of butchers and slaughter shops. There was a great variety of production sites where one could obtain a modest amount of meat at a low retail price or else butcher an injured or aged animal, using all its parts thanks to the shrewdness that thrifty kitchens always know how to manifest. The breeder had available the meat, which he preferred to sell, and the dairy products, which he willingly sold but from which he also fed himself, hoping to save the animals for sale and for breeding. Finally he sold the skin, which often was more profitable than the meat.

From goatskins he crafted gloves, leather for binding books, pouches (wineskins) to transport wine and oil, and so forth. The pouch was a skin turned inside out, with the skin on the inside stitched so that the contents would not leak. I hardly dare think what might be the taste and bouquet of oil and wine stored in such wineskins, but they were convenient containers for transportation, especially on muleback.

In the regions of greatest olive oil production—western Liguria, for example—goats were raised to furnish skins. Since the pouches were produced by the hundreds, hundreds of goats were needed. The meat and milk (transformed into cheese) were secondary products offered for popular consumption. Goat meat was available in great quantities in the valleys of production and became inexpensive daily fare. Shoemakers and tanners, with the help of contracts drafted by notaries, appropriated all the skins a slaughterer might produce in a year. The butcher considered the skin and the horns the “fifth quarter” of the ox (this locution is found even today in the traditions and special jargon collected by chambers of commerce).

I shall discuss pork later when I deal with sausage products, rich with added commercial value. Salami, pork belly, and hams are far more profitable than fresh meat, although in some European regions and later in America open-range breeding of hundreds of animals offered the possibility of adding fresh pork to the popular diet.

The raising of farm pigs involves labor costs, and feed had to be obtained by the breeder. Wild or semiwild pig farming costs less and offers a quality product with respect to the yield in meat. Germany and France, with their great forests, put large quantities of pork on the market at prices accessible to many. The Italian Apennine farmers raised pigs, as did to an even greater extent those in the southern Apennines, where one could purchase an entire herd of pigs to drive to the cities of the peninsula. Iberian pig farmers are still renowned for the products of their sierra.

To complete this review of meat resources available to the lower classes (and not always disdained by the ruling classes), I must note that horses, donkeys, and mules made a more than negligible contribution to the food chain and therefore to the production of leather and hides as well.

The cavalries of Charles V, François I, and Suleiman the Magnificent wore out thousands of saddles and harnesses (not to mention the leather used for the halyards of sailing ships and other leather products). The horses were slaughtered when wounded, and their meat was, and is, appealing and edible. Donkeys yielded very good meat, and mules, which by the thousands tracked along mountain trails, provided meat intended for sausage (blended with pork and pork fat).

Muslim enclaves, later absorbed into Christian society, left a legacy of consumption of salt-preserved donkey, horse, and mule. Mandrogne, in the Piedmont, kept up this custom at least until the 1950s. If this custom were ascribed to small Islamic enclaves, we would not be astonished, but I prefer to put forth an explanation confirmed for me by the fact that evidence for the consumption of horse, donkey, and mule flesh is found above all along the roads that lead from Genoa to Milan and from Genoa, via Cremona, to Venice, roads frequented by thousands of mules, donkeys, and horses.

As for meats produced by salt-curing horsemeat, these were not preserved to prevent spoilage nor to add commercial value (if there were any it would be slight) but rather to make edible a product that would otherwise be too tough to chew.