The Tratado, the Jesuits, and the governance of souls

Introduction

Nobody seems to want to go to prison and yet it has provided a surprising number of people with the opportunity and some might say inspiration for some of the most moving literature that the world has ever known. Consider the Travels of Marco Polo, which was committed to paper in 1298, while Polo was in a Genoese prison. The Travels encouraged generations of Europeans to dream of far-away lands abounding in fabulous riches that were strange and exotic—where men might have long tails and heads like dogs.1 Although Polo wrote at considerable length of China (Cathay), what particularly fired the imaginations of Europeans were his brief comments about an island to the east of China called Cipangu. According to Polo it was inhabited by a good-looking people with fair complexions and good manners who were awash in gold, fine pearls, and precious stones.2

Little more was heard of Cipangu until 1549, when Francis Xavier initiated a sustained Jesuit commentary on what was now referred to as Japão.3 The Japan that Portuguese sailors and Jesuits “discovered” in the 1540s was a society in the throes of profound changes, including a rapidly expanding and highly mobile population, increased urbanism and trade, and political instability, evidenced by frequent wars between aspiring members of a feudal warrior class, the bushi or samurai. In Japan, as in Europe, a religious elite wielded considerable power, including fielding armies of Buddhist monks who sought to protect and expand the interests of particular temples and sects.4

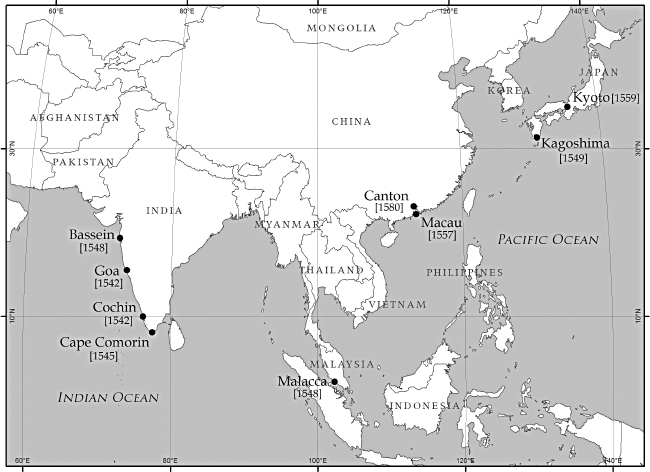

Map 1. Jesuit Missionary Activity in Asia to 1585

When Portuguese traders and the Jesuits happened on the south coast of Japan,5 both were embraced by a small number of Japanese lords or daimyo who sought to use Christianity and Western goods, including firearms, to advance their political interests. Between 1549 and 1585, a relatively small number of Jesuit missionaries,6 beginning with Francis Xavier, used this window of opportunity to establish some 200 churches with upwards of 150,000 Japanese converts, principally on the southern-most island of Kyûshû.7

In 1585, at the very height of Jesuit success, a twenty-year veteran of the Jesuit mission to Japan, Luis Frois (1532–1597), drafted the earliest systematic comparison of Western and Asian cultures.8 Frois’ comparative study apparently was not conceived as a book to be published. The manuscript, which is thirty-three folios, with text front and back, was written in Portuguese and has no title per se. Just below “Jesus [and] Mary”—a dedication at the top of the first page—the first line of the manuscript reads tratado em que se contem muito susinta e abreviadamente algumas contradisões e diferenças de custumes antre a gente de Europa e esta provincia de Japaõ (see Figure 1). The same line in English reads: treatise containing in very succinct and abbreviated form some contrasts and differences in the customs of the people of Europe and this province of Japan. The bottom half of the title page and page two of the Tratado list fourteen chapters on subjects as varied as gender, child rearing, religion, medicine, eating, horses, writing, ships and seafaring, architecture, and music and drama. Interestingly, whereas most Jesuit missionary texts from the period are dramatic narratives (i.e. epistles/letters, histories, dialogues) intended for the public as well as a Jesuit audience, the Tratado is a catalogue of over 600 numbered distichs or brief couplets, again divided among fourteen chapters. The following distich is from Chapter 9 (Figure 2), which is titled “Physicians, Medicines and Mode of Healing:”

11. Among us, abscesses are treated using intense heat; the Japanese would rather die than use our harsh surgical methods.

Here Frois sought to convey to fellow Europeans (implied by “us” and “our”) how the Japanese perceived Western medical practices as harsh or invasive. Similarly, in the following distich from Chapter 2, which is entitled “Women, Their Persons and Dress,” Frois rather dispassionately described the Japanese attitude toward female chastity:

1. In Europe a young woman’s supreme honor and treasure is her chastity and the inviolate cloister of her purity; women in Japan pay no mind to virginal purity, nor does a loss of virginity deprive them of honor or matrimony.

As detailed below, we believe Frois and his Jesuit superior, Alessandro Valignano, drafted the Tratado as a pedagogical tool to explain Japanese customs to European Jesuits recently arrived in Japan. Quite unlike Marco Polo or other would-be ethnologists (e.g. Mandeville, Isidore of Seville, Pliny, Herodotus), including contemporary and fellow Jesuit, José de Acosta,9 Frois based his comparative study almost entirely on first-hand observation. Moreover, rather that relegate Japanese difference, excepting perhaps Buddhism, to Homo monstrum or the work of the devil, Frois attributed it to rationally-based choice.10 As suggested, this understanding that civilized and European were not necessarily the same thing undoubtedly sprang in significant part from Frois’ many years studying the Japanese language and his more than twenty years residence in Japan.11 Paradoxically, Frois’ generosity—the many instances where he states or implies that Japanese customs were on a par or even superior to European practices—remains problematic, inasmuch as it is Frois, the European (not the Japanese), who judges, makes distinctions, categorizes, and pronounces.12 Moreover, for all his respect, neither Frois nor his fellow Jesuits recanted their “mission from god,” even when it led—as it often did—to the razing and burning of temples and the upending of many thousands of Japanese lives.13

Figure 1. Photocopy of Title Page of Tratado

Figure 2. Photocopy of First Page of Chapter 9 of the Tratado

Luis Frois: jesuit missionary and author

The Tratado was discovered after World War II by Josef Franz Schütte, S.J., in the Real Academia de la Historia, in Madrid, Spain.14 In 1955, Sophia University published a German-language edition of the manuscript, edited and translated by Schütte.15 The edition also contains a transcription of the original Portuguese, which has been used by scholars to generate editions in Japanese, Chinese, French, Spanish, and modern Portuguese. Somewhat surprisingly, this is the first critical, English-language edition of the Tratado.

Although the Tratado is not signed and lacks other direct evidence of authorship, scholars universally have followed Schütte in attributing the manuscript to Luis Frois.16 There are striking, substantive similarities between the Tratado and a table of contents for an otherwise missing Part I of Frois’ Historia de Japam,17 which was written around the same time as the Tratado. Moreover, Frois was perhaps the only Jesuit who had the knowledge of Japanese language and culture that is evident in the Tratado.18 This knowledge, and Frois’ substantial respect for Japanese customs, is apparent in the letters Frois wrote during the years preceding the drafting of the Tratado.19

Frois was born in Lisbon in 1532 and was given the name Polycarp at birth. Not much is known about Frois, although it is apparent that he was born into a mercantile or otherwise affluent family that could provide him with a quality education. In practical terms this meant learning to read and write in Portuguese and Latin.20 This education made possible at age thirteen Frois’ employment as an apprentice scribe in the Royal Secretariat in Lisbon. Although by 1545 rag paper and the printing press had ushered in a communication revolution, the functioning of government and society, more generally, still hinged on scribes who drew up all manner of decrees, contracts, legal decisions, exams, licenses, etc. Scribes essentially operationalized the wishes of the rich and powerful; they were accordingly respected and well paid.

During Frois’ childhood, his city of birth, Lisbon, was the hub of Portugal’s far-flung empire—an empire secured financially in 1498 when Vasco de Gama stunned the Western world by reaching India and establishing a sea route to Far Eastern markets.21 For the next sixty years or so Portugal enjoyed a near-monopoly on the importation of pepper and other expensive spices.22 Frois as a child would have watched ships from Asia, Africa and America arrive in Lisbon harbor—unloading slaves, precious spices, gold, and all manner of exotic plants and animals.23 (In 1515, King Manuel I staged a fight between an elephant and a rhinoceros for the amusement of the queen!)24 And then there were the parades of new found peoples from places such as Africa, Brazil, and India.

In 1540, King John III of Portugal invited a new religious order, the Society of Jesus, to Lisbon. The Jesuits (Francis Xavier and Simon Rodriguez) began a mission at All-Saints Hospital and quickly won popular acclaim for their work with the city’s poor and infirm.25 The young Polycarp apparently was among those impressed by the black robes, for Frois rather suddenly—at age sixteen—abandoned his career as a scribe and entered the Society of Jesus, taking as his new first name, Luis. Within a month, during the spring of 1548, Frois left home forever, sailing from Lisbon down the west coast of Africa, around the horn of Africa, and then on to India.26

Frois undertook a two-year novitiate in Goa at the recently-founded Jesuit College of Saint Paul. Goa already had a reputation as a colonial paradise, seemingly celebrated by Camões in his 1572 epic poem Os Luisadas.27 Frois, however, was destined for the priesthood and followed his novitiate with a “tertiary” year, during which he essentially demonstrated he had internalized a Jesuit identity. The heart and soul of this identity is the “Spiritual Exercises” of Ignatius of Loyola. The Exercises involve a stepwise progression of prayer and reflection, during which the Jesuit engages God in a “devout conversation”—a conversation that ideally endures with regular infusions of grace, helping the individual Jesuit realize and perfect his vocation.28 In 1551, the main vocation of the Jesuits was missionary work—attending to the corporal and spiritual needs of European Catholics and the innumerable gentiles lately “discovered” in Goa and other parts of Asia.29

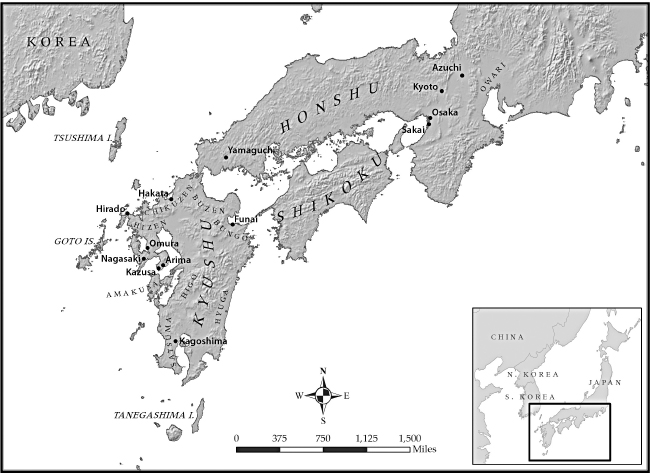

Map 2. Jesuits in Japan, 1585

Having completed his novitiate and tertiary year, Frois left Goa in 1554 and travelled to Malacca. Here he worked for three years before returning to Goa in 1557 to complete his studies as a scholastic.30 Because of his talents as a writer,31 Frois was tapped to serve as assistant to the Jesuit Provincial of India, who entrusted Frois with the annual report for India and other correspondence with the Church and the Society of Jesus in Portugal and Rome.32 During these early years—in 1553, to be precise—Frois had the opportunity to meet Francis Xavier, the Basque Jesuit who landed at Kagoshima in August, 1549, initiating the Jesuit mission to Japan. While the Jesuits took satisfaction in winning souls from among the poor, dark-skinned peoples of Goa, the Japanese and Chinese had white skin and were as civilized as Europeans!33 Or so Francis Xavier wrote in his stirring letters, which Frois undoubtedly read before they were bundled with other letters from Asia and shipped from Goa to Europe.

Frois was ordained a priest in 1561 and apparently petitioned to be sent to Japan,34 for late in 1562, at age thirty, he left Goa and sailed first to Macao and then on to the southern-most Japanese island of Kyûshû. Here during the previous decade, the Jesuits and Portuguese traders—with their access to guns and silk—had been embraced by the powerful daimyo of Bungo, Õtomo Yoshishige. With the daimyo’s blessing, Fathers Torre and Vilela and several Jesuit brothers followed up on Francis Xavier’s initial success and baptized perhaps a thousand or so Japanese, mostly in and around the town of Funai. Several hundred additional converts were made during brief visits to various parts of the island such as Satsuma, Yokoseura, Hakata, and Hirado.35 Jesuit success in Funai among Õtomo’s subjects was enhanced in 1557 when a former merchant and surgeon turned Jesuit, Luis de Almeida, used his personal fortune to open a hospital and foundling home for needy Japanese.36

Frois spent his first two years in Kyûshû (1563–1564) in Takashima and the port town of Hirado, where he continued his study of Japanese and attended to a small Japanese-Christian community as well as Portuguese merchants and sailors who visited the port on a regular basis.37 Once his proficiency in Japanese was established, late in 1564 Frois was sent to the main island of Honshu and the capital city of Kyoto, to work with Father Gaspar Vilela. Earlier the Jesuits had used their friendship with the daimyo of Bungo, Õtomo, to secure an audience with the shogun, who allowed Vilela in 1560 to begin missionary work in and around the capital city. By the time Frois arrived in Kyoto, Vilela and a remarkable Japanese assistant named Lourenço had won over a number of prominent daimyo and their samurai supporters. However, no sooner did Frois arrive in the capital, during the summer of 1565, when the shogun was assassinated and fighting raged between competing daimyo, which forced Frois and Vilela to flee Kyoto. Frois moved to Sakai where he worked for the next four years, devoting part of his time to preparing Japanese-language editions of the catechism, lives of the saints, sermons, and other texts for mission converts.

In 1568, the ever-changing political landscape of Japan witnessed the political maturation of Oda Nobunaga (1534–1582). Nobunaga was a minor warlord from Owari Province who spent a decade out-smarting and out-muscling fellow clansman and neighboring warlords. In the fall of 1568, Nobunaga triumphantly marched into Kyoto, where he installed a new shogun, who was in turn embraced by the emperor. Both the shogun and emperor were beholding to Nobunaga, but not so the Buddhist monks of the powerful Tendai sect who resided near Kyoto on Mt. Hiei. In part to counter the monks’ influence,38 Nobunaga allowed the Jesuits to return to Kyoto. The following year (1569), Frois was the first Jesuit to take up residence in the city, which had a population of close to 100,000.39 Like Lisbon, Kyoto was home to the Imperial court. For centuries, it had been Japan’s economic, political, and cultural center.

It had been seven years since Frois arrived in Japan and clearly he had mastered Japanese. Nobunaga was a difficult man to impress but apparently got on well with Frois,40 whom he granted permission to proselytize within his domain. Frois and a handful of fellow Jesuits, notably Organtino Gneechi-Soldo, enjoyed considerable success in the region about Kyoto over the next eight years or until 1577, when civil strife, coincident with a challenge to Nobunaga’s rule, once again forced Frois and his Jesuit colleagues to flee central Japan and take refuge to the south, in the province of Bungo. It was while serving as the local superior of the Bungo mission that Frois received word that the Jesuit “father visitor,” Alessandro Valignano, had arrived in Japan to conduct an inspection of the mission. As visitor, Valignano enjoyed the authority of the Father General of the Society, meaning that he could make whatever changes he felt necessary, regardless of the views of the local Jesuit superior, Francisco Cabral.

Valignano knew or soon learned of Frois’ impressive grasp of the Japanese language and culture and made Frois his assistant and translator. For the next three years (1579–1582) Frois travelled to various parts of Japan, helping Valignano assess Jesuit operations. At the end of Valignano’s inspection in 1583, at age fifty-one, Frois was entrusted by Jesuit superiors to write a history of the Jesuit mission enterprise. Much of Frois’ subsequent career as a Jesuit (Frois died in 1597) was spent writing this multi-volume work, which covered the entire history of the Jesuit experience in Japan until 1593.41 As noted, an extant prologue and table of contents for Frois’ Historia is strikingly similar to the Tratado.42 The title page of the Tratado bears a date of June, 1585, indicating that it was written at roughly the same time as Part I of Frois’ Historia.

The cultural-historical context of the Tratado: A Jesuit mission in peril

While it seems certain that Frois wrote the Tratado, apparently basing it on Part I of his history (or vice versa), nowhere does he make explicit why he drafted the text and for whom it was intended. Because most distichs in the Tratado reference Europe in terms of “we,” “us,” and “ours,” the text obviously was written for a European, rather than a Japanese audience. Because the Tratado contains Japanese terms that are not translated, it would further seem that the text was intended for European Jesuits, presumably those recently arrived in Japan who were expected to learn Japanese. Along these lines, the title page of the Tratado indicates that it was drafted in Canzusa (Kazusa), which was in the province of Arima on the southern end of the Shimabara peninsula. Kazusa was home to a Jesuit college for novices and scholastics and was also where Frois resided while serving as socius or assistant to the Jesuit vice-provincial Gaspar Coelho.43

The Tratado’s central focus—Japanese customs, particularly among elites, and how they differed from European behaviors and beliefs—was a major preoccupation of Frois’ immediate superior and the highest ranking Jesuit in Asia, the father visitor Alessandro Valignano.44 When Valignano arrived in Japan in 1579, having spent the previous five years in India and Macao, he quickly realized that the reports he had been receiving from Japan exaggerated Jesuit success.45 Although the Jesuits could boast upwards of 150,000 Japanese baptisms, a good number of daimyo had embraced Christianity to gain access to Chinese as well as European trade goods, including guns. Prior to the 1540s and the arrival of the Portuguese, Japanese pirates46 had plundered settlements along the coast of China, prompting the Chinese to forbid all trade with Japan—this despite Chinese interest in Japanese silver and the latter’s desire for Chinese silk.47 Portuguese merchants, who traveled in state-of-the-art ships (see chapter 12) and essentially were required by the Portuguese Crown to facilitate the work of the Jesuits, seized the opportunity to act as middle-men in a reinvigorated trade between Japan and China and all of Asia and beyond.48 Japanese elites quickly realized that befriending a Jesuit could open doors to Chinese silk and weap ons. Indeed, to fund their mission enterprise in Japan, the Jesuits invested large sums of their own money in Chinese silk, which was delivered to Japanese ports by Portuguese merchants.49

Valignano became rightly suspicious of the motives of not only the daimyo, but of Japanese commoners, who were in the habit of following the example of their rulers. Arguably, neither daimyo nor commoners had sufficient knowledge of Christianity, which had been explained by fellow Japanese trained in the basics by the Jesuits.50 Both segments of Japanese society were likely to abandon Christianity (and the Jesuits) at the first sign of significant opposition. And there was ample trouble in the form of Buddhist monks who at first tolerated, but subsequently opposed the Jesuits.51 Unlike the New World, where the Jesuits followed in the wake of introduced diseases that undermined native religions,52 Japan suffered no demographic and cultural collapse coincident with the arrival of Europeans.53 Buddhism and Shinto remained alive and well in Japan, even if the abbots of some Buddhist temples alienated their followers by embroiling themselves in power struggles with Japanese nobles.54 In this regard, powerful daimyo such as Nobunaga and Hideyoshi, both of whom embraced or tolerated the Jesuits, never rejected or opposed Buddhism per se. Their problem was with particular Buddhists (i.e. Tendai of Mount Hiei, Shingon of Negoro, monks of Osaka) who fielded armies and otherwise opposed Nobunaga’s and Hideyoshi’s hegemony.55

Valignano worried about not only the Japanese, but his fellow Jesuits, many of whom looked down on the Japanese, who everyone acknowledged, beginning with Francis Xavier, were an incredibly proud people.56 Contrary to Valignano’s own orders, which had been conveyed over the years from India and Macao, Jesuit superiors, particularly Francisco Cabral, the resident superior of the Japan mission, had made little effort to train European Jesuits in the Japanese language. Still more disturbing, Valignano discovered that Cabral and his assistants had systematically discriminated against those Japanese who had aspired to the priesthood or who had sought admission to the Jesuit order; the Japanese were relegated to a class of assistants or dojuku, rather than receiving training as scholastics.57

In point of fact, the Jesuit mission enterprise in Japan was a proverbial “house of cards” that might collapse at any moment. Valignano astutely realized58 that if the Jesuits and Christianity were to have a future in Japan, it was imperative that the Jesuits embrace Japanese customs as well as the Japanese language, and in the process learn to compete with Buddhist monks, who often were masters of both old and new traditions such as calligraphy, poetry, and chanoyu or the “way of tea.”59 Importantly, Valignano realized that his fellow Jesuits would have to embrace not only Japanese language and culture, but his soon-to-be-revealed plan to train Japanese converts for the priesthood. No European power, including Habsburg Spain, had the men and resources to invade Japan and introduce European juridical authority and institutions (e.g. audiencia, inquisition, universities, cathedrals), which would greatly facilitate the conversion of the Japanese to Christianity. This was of course what happened in colonial Mexico and Peru. It was further apparent, particularly given the challenge of the Reformation back in Europe, that there would never be enough European priests to convert, never mind staff a Catholic Church in Japan. Confronted with these realities, Valignano concluded that the only hope for Japan was a Church staffed by the Japanese themselves. In one of his characteristically blunt letters to superiors, Valignano wrote:

Japan is not a place which can be controlled by foreigners, for the Japanese are neither so weak nor so stupid a race as to permit this, and the King of Spain neither had nor ever could have any power or jurisdiction here. Therefore, there is no alternative to relying on training the natives in the way they should go and subsequently leaving them to manage the churches themselves.”60

A Catholic Church staffed by non-Europeans was unheard of at the time, owing to the long-held belief that only Europeans could be entrusted with the mysteries and sacraments of the Roman Catholic Church. Although Jesuit correspondence published in Europe cast the Japanese as civilized, the Jesuits also reported that the Japanese had traditions of infanticide, suicide, and pederasty. In part, to assuage any European doubts about the wholesomeness of the Japanese, Valignano sent four Jesuit-educated Japanese teenagers to Europe as envoys to Rome in 1582. The teenagers arrived in Lisbon in 1584 and over the course of twenty months visited some seventy towns and cities where they were received by Catholic elites, including the regent of Portugal, the King of Spain, the doges of Venice and Genoa, and two popes (Pope Gregory died and was replaced by Sixtus during the legates long stay in Rome).

The four young Japanese converts were ostensibly actors in a conversion drama orchestrated by the Jesuits to impress Europe’s Catholic elite and to secure their support of the Jesuit enterprise in Japan.61 The drama as such featured a Japanese “other” who was paradoxically civilized yet antipodean (a central theme of the Tratado), who was rendered fully civilized or un-problematically so as a result of conversion to Christianity. This drama was staged by repeatedly having the Japanese appear in native dress and by having the Japanese perform their “curious” Japanese customs (e.g. tea ceremony) alongside what were understood as more advanced, European behaviors. For example, the Jesuits had the Japanese dress in kimonos and give public demonstrations of eating with chopsticks. Often on the same day the Japanese would attend Mass, and while in Rome, the opera, appropriately attired in European clothing and dutifully exhibiting the appropriate respect for and understanding of European ritual (e.g. removing hats, genuflecting).62

The Tratado and the education of European Jesuits

The visit to Europe by the Japanese teenagers was still two years in the future when Valignano, in 1580, convened a momentous meeting of the Jesuit order in Bungo, Japan. At the meeting the father visitor unveiled his new programs to train Japanese converts for the priesthood and to train European Jesuits to behave in accordance with Japanese language and culture.63 We believe Frois drafted the Tratado at the behest of Valignano as a teaching tool, to clarify for European Jesuits fundamental differences in Western and Japanese cultures. Again, what is significant is Frois’ explicit recognition that one need not think and behave as a European to be civilized. Thus in the title page of the Tratado, he essentially warns his reader not to be surprised that “…one can find such stark contrasts in customs among [us and] people who are so civilized, have such lively genius, and are as naturally intelligent as these [Japanese].”

Certainly the substance of the Tratado is consistent with Valignano’s plan to train European Jesuits to behave as Japanese. As noted, Frois drafted over six hundred distichs that deal with a wide variety of customs, ranging from sleeping to gift giving. The Tratado at the same time reveals a particular concern with behaviors and beliefs that were critical to Jesuit success in Japan. Chapters one through three, for instance, focus on gender and child-rearing practices. Several generations before the Jesuits arrived in Japan, the nation’s unity, which had been maintained by the Emperor and his military commander, the shogun, was shattered when hundreds of once-cooperative nobles and “knights” (samurai) as well as militant abbots began putting their own interests above those of the Emperor and the handful of clans that had ruled Japan for centuries. The very lives of European Jesuits—never mind whether they could proselytize—depended on the Jesuits comprehending the complex gender roles of the nobility and the samurai class, and how these roles were inculcated in Japanese children.

Because the samurai, nobility, and Buddhist elite enjoyed particular privileges (e.g. distinctive clothing, weapons, riding a horse) and often were supporters of the “arts,” Frois also has chapters on subjects as different as horses, letters and writing, and drama and music. A chapter with seemingly less obvious import, chapter six, focuses on Japanese customs with regard to eating and drinking, including chanoyu or the “way of tea.” The eating habits of Europeans (e.g. use of hands, emphasis on meat) deeply offended the Japanese and early on became a serious stumbling block in terms of Japanese respect for Europeans and by extension, Christianity. The Japanese, in fact, considered Europeans “slobs” (sucios).64 One of Valignano’s first mandates was that European Jesuits eat in the manner of the Japanese (e.g. chopsticks, small bite-size portions, rice instead of bread, less meat). Valignano also mandated that Jesuit residences—built in the Japanese fashion (thus Frois’ Chapter 11 on architecture)—include a reception room where guests would be served tea by a chanoyusha, that is, somebody trained in tea etiquette.65 During the sixteenth century rather distinct Japanese traditions of consuming tea—one followed by Zen monks and the other by literati and nobles who shared poetry and their collections of Chinese art objects—merged to form chanoyu. The “way of tea” as defined by Sen Rikyu (1522–1591), which was embraced by Japanese warlords, combined the ritualized, contemplative sharing of tea with an engagement with art. Now, however, the art objects, particularly the tea service, were valued not because they were necessarily Chinese or expensive, but because they conveyed in their simplicity and rusticity transcendent truths (e.g. “chill,” “withered,” “lean”) that long had been celebrated by renga poets and appreciated by reclusive hermits and wandering monks. As Hirota has pointed out, chanoyu was all about the “…dissolution of the habitual, mundane frames of reference within which the things of the world are identified and gauged.”66

Frois’ literary model, relativism, and comparisons

At the time Frois wrote, the term “tratado” or treatise was used to refer to a work that was explicitly pedagogical and didactic rather than argumentative in the Scholastic or modern sense of the term (i.e. a work that poses a question and then pursues it systematically, realizing a conclusion).67 As noted, the Tratado is not an argument per se about whether, for example, the Japanese were civilized. At the very outset of the Tratado (i.e. title page), Frois asserts this as a “fact.” Working with this given, the Tratado describes some of the differences between European and Japanese customs. The Tratado as such, particularly Frois’ use of the distich, was entirely consistent with Valignano’s plan to engender a Jesuit understanding of Japanese customs or “frames of reference.” In this regard, Frois presumably drafted the Tratado with the idea that his couplets would serve as a point of departure for more nuanced discussion of Japanese behaviors and beliefs. This presumption seems warranted in light of Frois’ use of qualifiers such as “generally” or “for the most part.” Moreover, Frois devoted much of the prologue to his Historia to a discussion of how comparing customs was potentially misleading. Consider, for example, Frois’ discussion of the handkerchief and Japanese use of what today we call tissues or Kleenex:

Told that the Japanese blow their nose but once per handkerchief, the European reader will find it odd if not ludicrous. It is like being told that the kings of Malabar eat just once from the same plate. They eat on banana leaves, so when the meal is over they throw them away. Thus, when it is said that once a handkerchief has been spit in or blown upon, the Japanese throw it away without washing it, the following must be explained: the Japanese go about with many thin, handkerchief-like, folded papers in their pocket [bosom], instead of a handkerchief. As this paper is very cheap, for a very small outlay [of money], they can use as much as they please.68

The use of the distich as a point of departure was entirely consistent with the scholastic method, which often entailed posing a question to which there were discordant answers, supported by strong evidence. Contrasts that entailed contradiction69 functioned as a “hermeneutic irritant,” engendering insight, including the realization that two different things can be true at the same time (e.g. two societies with very different customs can both be civilized).70

One of the most influential examples of the pedagogical use of distichs is The Distichs of Cato, which was the most popular textbook on Latin and ethics during the Middle Ages.71 Cato was still prized during the sixteenth century (Erasmus, among others, published an edition) and very likely figured in Frois’ education and that of fellow Jesuits.72 The Disticha Catonis ordinarily was read to students by school masters who used the couplets as the starting point for a discussion of Latin grammar as well as matters of virtue and morality. In the prose introduction to the Disticha Catonis, “Cato” outlined his purpose, which paralleled Valignano’s and Frois’ concern with making sure that young Jesuits from Europe behaved properly in Japan:

When I noticed how very many men go seriously astray on the path of morals, I decided that their judgment should be aided and advised, especially so that they might live gloriously and attain honor. Now, Dearest Son, I shall teach you how to form good morals for your mind….73

Whatever Frois’ literary model, or models, his distichs generally are neutral or explicitly respectful of Japanese customs. For instance, most of Frois’ contrasts in Chapter 2, which focuses on women, steer clear of value judgments:

56. When wearing a head covering, women in Europe cover their faces all the more when speaking with someone; Japanese women must remove their scarf, for it is discourteous to speak with it on.

Of course, Frois was a product of his times, and not unlike modern ethnographers and ethnologists,74 he at times fashioned contrasts that implied that Japanese customs were less than rational. In chapter 2, for instance, Frois implicitly belittled Japanese names:

47. Among us, women’s names are taken from the saints; the names of Japanese women are: kettle, crane, turtle, sandal, tea, bamboo.75

Worse yet—from the perspective of cultural relativism—are Frois’ chapters on Buddhism and Buddhist monks (Chapters 4 and 5). Frois casts Buddhist monks as charlatans or money-grubbing pedophiles, ignoring the widespread abuses of his own Catholic Church, which was torn apart during Frois’ own lifetime. It should be noted that Frois’ “sins” in these two chapters cannot be attributed to ignorance, as Frois spent considerable time conversing with Buddhist monks. Indeed, Frois and fellow Jesuit Organtino Gnecchi-Soldo were tutored for a year by a former Buddhist monk.76 Because he was a Jesuit “on a mission from God,” Frois apparently was unwilling to entertain the possibility that Buddhism represented a reasonable alternative to Christianity.77 Moreover, if, as suggested, Frois wrote for a young, European-Jesuit audience—an audience that would face ample challenges as missionaries in Japan—then one can well imagine Frois and Valignano not wanting to further try their faith by inviting meaningful comparisons between religions.78

While the Tratado does not always reflect the ideals of modern ethnology (i.e. cultural relativism; systematic, “objective” comparison) it comes surprisingly close, shedding valuable light on sixteenth century Europe and Japan. The reader will note in this regard that Frois chose to contrast Japanese with European, rather than Portuguese customs.79 Reading the Tratado, it becomes apparent from Frois’ distichs on subjects such as food, architecture, drama, and religion that “Europe” for Frois meant Mediterranean Europe, namely Portugal, Spain, southern France, and Italy. This thoroughly Catholic part of Europe80 supplied the vast majority of Jesuits sent to Japan, particularly after 1570. For instance, the largest contingent of Jesuits sent to Japan was recruited by Valignano and sailed from Lisbon in 1574. Valignano brought with him seven Italians and over thirty conversos (!) that he had recruited from Jesuit colleges and houses in Spain.81

Frois probably also spoke of European, as opposed to Portuguese customs because in 1548, when he left Europe, the idea of national identities was just emerging.82 The nation states we know today (e.g. Portugal, Spain, France, Italy) were in their infancy. People often were distinguished by regional dialects and customs, which coalesced in Europe’s larger cities.83 Lisbon, in particular, was as cosmopolitan as any city in Europe and home to large numbers of merchants, craftsmen, artists, and adventurers84 from northern as well as southern Europe. Bankers from Italy and Germany, for instance, flocked to Lisbon, where they invested heavily in Portuguese ships that set sail for Africa, the Far East, and Brazil.85 Portuguese scholars as well as the sons of Portuguese nobility often studied outside Portugal, in France, Italy, and Spain.86 The Portuguese art scene likewise was crowded with Flemish painters, some of whom settled in Lisbon and adopted Portuguese names (e.g. Francisco Henriques). The dominant influence on Portuguese literature in 1550 emanated from “Italy,”87 and correspondingly, printing houses in Venice supplied most of the books read in Portugal (and Spain).88 The Portuguese queen invariably was Castilian, and Castilians were prominent among Portugal’s elite, so much so that Gil Vicente wrote close to half his theatrical works in Castilian.

Thus, while the notion of Europe or European remain to this day contested, it is understandable that Frois spoke of European rather than Portuguese customs.

The Tratado and the governance of souls

The Tratado and Valignano’s twin initiatives of embracing Japanese customs and creating a Japanese clergy can be seen as significant departures from European colonialism in as much as they seem to imply a respect for and even the empowerment of a Japanese other.89 In this regard, scholars long have acknowledged the impressive ethnographic and linguistic literature produced by Jesuit missionaries during the sixteenth and seventeenth centuries. Jesuit grammars and artes of non-Western languages such as Japanese, Guaraní, or Cahita continue to be valued by linguists.90 Similarly, anthropologists, literary scholars, and historians have marveled at the “proto-ethnographies” of non-Western peoples compiled by the likes of Blas Valera, Pérez de Ribas, Paul LeJeune, or Mateo Ricci.91 Significantly, the Jesuits “walked the talk” of cultural relativism, for instance, supplying their Guaraní neophytes in Paraguay with firearms so they could resist Luso-Brazilian slave raiders (“Paulistas”).92 In northern Mexico, the black robes often blocked Spanish miners from exploiting Indian labor. And in Japan, as we have seen, the Jesuits led by Valignano made plans to create a Catholic Church that was staffed from the top down (bishops, clerics, and religious) by the Japanese themselves.93

The Jesuits’ “progressive” missions and texts often have been explained in terms of the Jesuit embrace of Renaissance Humanism and Thomism, which predisposed the Jesuits to see potentially virtuous pagans where others saw irredeemable savages.94 Jesuits were indeed thoroughly convinced (it was at the heart of their own religious election) that God’s grace was ubiquitous. Jesuits disembarking in Japan, China, or the Americas expected to find societies with serious flaws because these societies never had benefited from revealed truth (i.e. Gospels) and the sacraments. But the same Jesuits understood that God never would have abandoned his creation. Through the simple application of reason to the majesty of creation (as per Thomas Aquinas), many Indians or Asians were likely to arrive at some knowledge of and reverence for the one, true God.95 Jesuits, in fact, were open to the possibility that pagans got quite a few things right, so to speak.96

While it is true that the Society of Jesus was nourished by a revival of Thomism and the flowering of humanism, the half-century prior to 1540 also was an age of discovery that provided unprecedented European access to distant worlds that abounded in fabulous riches. The riches were difficult to secure, however, in the absence of European juridical control. As Valignano himself pointed out, neither Spain nor Portugal ever were in a position to successfully invade Japan and China and overpower the indigenous elite, installing European institutions and authority. It was much easier to transplant European juridical control (e.g. the audiencia, the presidio, bishoprics) in the New World, where the arrival of Europeans was coincident with epidemics that devastated the Indian population, killing countless elders and thus undermining indigenous authority.97 As noted, the arrival of Europeans in China and Japan did not precipitate a population collapse resulting from the introduction of infectious diseases.98

In Asia as well as frontier areas of Latin America, the inextricable Christian imperatives of commodity and spiritual conversion99 required an “indirect” means of gaining access to and control of the indigenous population. Arguably, the Jesuit mission met this requirement by operationalizing what Foucault has referred to as “governmentality.” In a series of lectures toward the end of his life, Foucault observed that, beginning in the sixteenth century, the exercise of power in Europe increasingly came to be based on disciplinary rather than juridical authority.100 Whereas polities during the Middle Ages were maintained by threat of force,101 increasingly during the early modern period they came to rely on a complex arrangement of various “technologies of the self,” which simultaneously championed freedom, all the while “free” human beings were busy disciplining themselves in accordance with socially-constructed truths about their identities. The sixteenth century witnessed the publication of books that mapped out in great detail “appropriate” beliefs, practice, and identities: The Perfect Wife (1585), The Book of the Courtier (c. 1521), The Education of a Christian Woman (1523), The Prince (1505), On Civility in Boys (1530). What Greenblatt102 has termed “Renaissance self-fashioning” was effected through a host of new and old disciplines (e.g. the theater) that provided Europeans from all walks of life with the opportunity to model their social performance after the roles delimited in texts, sermons, on stage, or in the visual arts.103

Interestingly, it is around the middle of the sixteenth century, when Foucault notes there is a huge outpouring of reflection and publication on the government of oneself, of one’s soul, of children, and of the state,104 that the Society of Jesus was founded by Ignatius Loyola. The new religious order alientated many contemporaries (i.e. Mendicants, secular clergy) precisely because it broke with the juridical or cenobitic model of religious life105 and flaunted what was a new technology of the self that balanced religious freedom with Christian zeal. The Jesuits ignored “purity of blood,” admitting conversos; they wore no distinctive garb; they were not permanently assigned to religious houses; they did not recite the divine office as a community; Jesuit superiors were obeyed, but not in defiance of one’s conscience. All this “freedom” was held in check by what Foucault termed techniques of disciplinary power such as yearly performance of the Spiritual Exercises (a well-defined religious retreat involving a general confession), regular letter writing between Jesuits, and the circulation and consumption106 of a public discourse (e.g. the anuas or “Jesuit Relations”) that celebrated the Jesuit “way of proceeding.”

Although the Jesuits frightened many traditional Catholics (not to mention contemporary “heretics” or Protestants), the order very quickly gained the favor of the Portuguese and Spanish Crowns and the Papacy, particularly because of its successful mission enterprises in Asia and subsequently America. As Bernard Cohn,107 among others, has pointed out, successful colonial ventures presuppose “cultural technologies of rule” that classify and naturalize indigenous subjects. In this regard, the Jesuits mastered indigenous languages and drafted impressive “proto-ethnographies” of indigenous peoples not because they were intent on celebrating difference or desired reciprocal understanding, but because systematically mapping difference facilitated the Jesuits’ unidirectional program for directed culture change.108 Knowledge of indigenous languages and customs was a prerequisite of operating within societies where the Jesuits were juridically powerless.109

Significantly, with knowledge of otherness the Jesuits proceeded to develop seminaries, boarding schools, and confraternities to transform (using, for example, Japanese and Latin editions of Western/Christian texts110) “good pagans” into true Christians. To quote one of Valignano’s assistants, Duarte de Sande, “…it is necessary to enter with theirs to come out with ours.”111 Writing to Valignano from China in 1583, Mateo Ricci reported “…we have become Chinese so that we may gain the Chinese for Christ.”112

The Jesuit mission to Japan, including Valignano’s liberal re-structuring of the enterprise appears entirely consistent with Foucault’s characterization of “governmentality.113 In Japan, as elsewhere, the Jesuits produced detailed studies of the Japanese language as well as an extensive “ethnographic” literature, including Frois’ systematic comparison of European and Japanese customs. As suggested, the Tratado apparently was drafted to help explain Japanese customs to European Jesuits, with the further idea that this understanding would make it easier to embrace certain customs. Note, however, that neither Frois nor Valignano (nor anybody else at the time) anticipated the modern anthropological understanding of culture as an integrated system of behaviors and beliefs—this despite the Tratado’s systematic survey of customs (e.g., chapters on gender, architecture, plays, writing, warfare, etc.). Like Montaigne, Valignano and Frois may have suspected or intuited that customs were interrelated114—that a society’s cuisine or architecture might be integrally related to its religious beliefs and practices. Nevertheless, neither Valignano nor Frois seemed concerned that European Jesuits who “lived like the Japanese” (i.e. following many of their customs) might become “destabilized,” assimilating if not valuing, for instance, Buddhist and Shinto values and beliefs.115 In keeping with Jesuit first principles as articulated by Loyola,116 Valignano and Frois believed that European as well as Japanese Jesuits were “formed” and steeled in a significant way (an essential identity) by the operation of the Holy Spirit and the embrace of a fundamental set of Christian/Jesuit beliefs and practices.117 This understanding was entirely in keeping with the Jesuit “way of proceeding,” which assumed that a Jesuit who remained connected to god and fellow Jesuits was free to follow their conscience and be adaptable with respect to externals (e.g., wear whatever is appropriate; pray when possible; help the poor or befriend a king).

Although the Jesuits principally were concerned with re-making their converts, they nevertheless went further than many of their European contemporaries in understanding and respecting difference. As Foucault pointed out, “governmentality”—regimes of diffuse power where people essentially discipline themselves—nevertheless entails a freedom to explore and embrace alternative behaviors and beliefs. Arguably, European Jesuits such as Frois, Organtino, and Rodrigues, who may have initially “performed” Japanese customs to access potential converts, discovered that the “performances” were satisfying and rewarding. In Japan and the Americas, the Jesuits did, in fact, accommodate indigenous traditions.118 However, it must be kept in mind that the Jesuits never questioned their “mission from God,” which was fundamentally about altering Japanese identity—even when it meant destroying Japanese lives119 If Valignano wanted fellow Jesuits to embrace Japanese customs, it was because he perceived this embrace of certain customs as largely inconsequential from the perspective of one’s fundamental identity and “soul.”120 Correspondingly, Valignano was willing to create a Catholic Church staffed by the Japanese, but only on the condition that the Japanese, beginning in childhood, were “formed” with an essentially Western/Christian worldview, imparted by the study of Latin and the consumption of a select (e.g. no Erasmus or Lucretius), Humanist canon that came to include works as diverse as the lives of the saints, Aesop, and Cinderella, all of which were edited and translated into Japanese.121 Again, these expressions of governmentality held the promise of rebellion—“there is no power without potential refusal or revolt”122—as Japanese trained by the Jesuits could, upon assuming positions of power as priests, “fall back” on whatever Japanese traditions they may have secretly cherished or rediscovered in later life. An excellent example of such rebellion is Fukan Fabian (1565–1621). Fabian was a Japanese convert to Christianity who received training as a Jesuit “scholastic” and was destined for ordination as a priest. Rather late in his life (1608), Fabian apostatized, subsequently authoring Ha Daiusu (1620), a sophisticated theological critique of Christianity as the one true faith.123

In the case of Japan, we can only speculate about what might have been, had Valignano’s plans for a Catholic Church been fully realized. Two years after Frois drafted the Tratado the Jesuit enterprise in Japan started to unravel. Japanese daimyo, particularly the most powerful of these elites, seemingly became frightened by the Jesuits or what they represented. For reasons that are still debated by scholars,124 Japan’s most powerful daimyo, Toyotomi Hideyoshi, became convinced in 1587 that the Jesuits posed a threat to his power and authority. Hideyoshi issued an order of expulsion, which while largely symbolic (only three Jesuits actually left Japan), marked the beginning of a tense decade that culminated in 1597 in the very public persecution of twenty Japanese Christians and six Franciscan friars. (The Franciscan order had come to Japan in 1593, over Jesuit objections.125) Bickering and competition between the Catholic orders contributed further to fears among Japanese elites and led in 1614 to a new round of persecutions, expulsions, and the widespread destruction of Christian churches. Those Christians who survived went into hiding until 1637–38, when they joined a peasant uprising (the Shimbara rebellion) that was promptly crushed. Henceforth the Tokugawa regime effectively closed Japan to Christian missionaries and what remained of the Catholic Church went underground.126 As an aside, today less than 1 percent of all Japanese consider themselves Christian; the overwhelming majority identify with Shinto and Buddhism127

Preparation of an English-Language edition of the Tratado

It was in recognition of the importance of the Tratado, both as a primary source for early modern Europe and Japan and an encounter text—reflecting the many forces that governed European perceptions and representations of others—that we undertook the preparation of an English-language edition of the Tratado. In preparing an English translation we have relied on Schütte’s transcription as well as a microfilm copy of the Portuguese original obtained from the Real Academia in Madrid. We have indicated in footnotes instances where we disagree with Schütte’s rendering of the Portuguese original, which is not altogether legible in places, owing to minor damage the manuscript sustained during the centuries prior to its discovery.128 Because the Tratado is in the form of over six-hundred brief couplets, rather than a narrative,129 our biggest challenge with respect to translation has been insuring lexical accuracy. Special attention has been given to the translation of Portuguese and Japanese terms whose meanings have changed significantly over the past four-hundred years. We generally have left un-translated Portuguese or Japanese terms with meanings specific to the sixteenth century. These cultural or temporally-bound terms are italicized and are discussed in footnotes. The reader will note that we especially have relied on Houaiss’ encyclopedic dictionary of the Portuguese language.130

It is perhaps the human condition to live out our lives unsure of the changes taking place all around us. Today, for example, we speak of “globalization,” but are at a loss to define adequately what may be a new historical epoch. Frois offered no reflection on how the societies and customs he compared might have been in flux (except perhaps when he used qualifiers such as “for the most part” or “generally”). And yet, it is difficult to imagine a period in the history of either Japan or Europe that was as dynamic as Frois’ lifetime (1532–1597). In Japan, the demise of the Muromachi shogunate in the late 1400s ushered in a century of warfare that intensified with the arrival of the Jesuits and Portuguese traders. Indeed, during what scholars have designated the Azuchi (ca. 1568–82) and Momoyama periods (ca. 1582–1600), which coincided with the “reigns” of Oda Nobunaga and Toyotomi Hideyoshi, respectively, the scale of violence seemingly reached unprecedented heights.131 And yet paradoxically, the Azuchi and Momoyama periods were a time of cultural fluorescence, as seen in the elaboration of the tea ceremony, the appearance of Kabuki, or the stunning perfection of various “material” arts (e.g. ceramics, lacquer, screen painting, castle architecture).132 As Masahide133 has pointed out, Japan during the Azuchi-Momoyama period also experienced a religious reformation of sorts, as it is during this period that the Pure Land tradition of Buddhism, earlier elaborated by Shinran (1173–1263), spread rapidly. The appeal of Shin Buddhism stemmed not only from its concern with the salvation of all people (rather than a select, mostly aristocratic few), but its doctrine that salvation required no esoteric or scholarly knowledge or practices, but a “simple” faith in Amida Buddha.134

Only in recent decades have we fully appreciated that all cultures are dynamic and contested. We should not be surprised that Frois spoke of customs as if they were static and invariable. Although one would think that Frois had a much better understanding of his own European culture, it might not have been apparent in 1548, when Frois left Europe for good, that Erasmus and Luther irrevocably had shaken the foundations of Christendom. During Frois’ lifetime Europe also was changed forever by the discovery of whole new worlds on the other side of the planet. The sixteenth century likewise witnessed a communication revolution in the forms of the printed book and broadside. Today we also look back and recognize the nation state, polyphonic music, opera, the rise of the bourgeoisie, and a host of other new societal forms and expressions.135

As noted, the Tratado consists of over six-hundred distichs, divided by Frois into fourteen chapters. Our translation of each of Frois’ distichs is followed by a brief commentary in which we clarify—with the benefit of hindsight—the contingencies (e.g., literary, theological, political, historical, cultural) that seemingly governed Frois’ representation of Japanese and European customs. Often in our commentaries we point out how Frois’ distichs are partial truths that actually pertained to a particular segment of European or Japanese society (i.e. elites), or to a particular time (e.g. summer, new year’s) or place (e.g. a shrine or tea house). Our work of contextualization was helped significantly by Akio Okada’s enormously popular Japanese-language edition of the Tratado.136 Similarly, we often turned to Marques’ Daily life in Portugal in the Late Middle Ages for an understanding of the European customs referenced by Frois.

Although the sixteenth century in Japan and Europe witnessed unprecedented change, Japanese and European cuisine, architecture, drama, and aesthetics—to name but a few arenas—are still to this day governed by distinct and enduring principles. Accordingly, we have drawn on the comments of perceptive Europeans who wrote about Japan subsequent to Frois, particularly Engelbert Kaempher (1690), Sir Rutherford Alcock (1863), Isabella Bird (1880), Edward Morse (1886), Alice Bacon (1893), Eliza Scidmore (1897), and Basil Chamberlin (1902). Like Frois, these Europeans spent many months or years in Japan and sometimes offered “thick” descriptions of Japanese customs.137 Along these lines, readers of our edition may be surprised (pleasantly, we hope) that our edition incorporates observations about present-day Japanese customs. Because most readers of our edition are likely to be Westerners, they will know that Europeans (for the most part) no longer beat their wives, eat with their hands, or attend hangings for entertainment. These same readers are not likely to know that the Japanese (for the most part) no longer eat dog, carry their children on their backs, or commit ritual suicide. We thought it important to reflect on present-day Japan, if only to preclude stereotypes of a timeless or tradition-bound Japan.

In general, our goal has been to convey the cultural-historical context of the Tratado and the dynamic and contested reality of Japanese and European cultures. The Tratado is a fascinating text because it reflects how humans know and constitute themselves both in relation to and distinct from others. We have tried to draw the reader’s attention to how this comparative “project,” which is an essential part of the human condition, can entail a narrow or ethnocentric logic. The Tratado suggests that cultures are amenable to formulaic statements. Arguably this type of thinking, which once heralded the birth of anthropology as a discipline, survives today in popular stereotypes of the Japanese, or in the case of the Japanese, of Westerners. In translating and commenting on Frois’ text, we have sought to emphasize how identities are sometimes rooted in empirical generalizations (e.g. Europeans do tend to be physically larger than the Japanese) but more often in contested social constructions. Being a man or woman, or modes of expressing or feeling pain, are, in fact, quite variable.

The very breadth of Frois’ Tratado, which encompasses topics as diverse as architecture, gender, shipbuilding, and childrearing, poses a challenge in terms of providing appropriate contextual information to appreciate Frois’ individual comparisons. To meet this challenge, the project has engaged an interdisciplinary group of scholars. Although each of us has handled multiple tasks, we each brought particular skills and knowledge to the text. Richard Danford was ultimately responsible for our translation from Portuguese into English; Robin D. Gill, who, like Frois, lived in Japan for over twenty years, supplied commentary and insight into the Japanese language, culture, and history; and Daniel Reff provided insight into the Jesuits and early modern Europe.

1 Syed Manzurul Islam, The Ethics of Travel, From Marco Polo to Kafka (Manchester: Manchester University Press, 1996), 120, 143; Geraldine Heng, Empire of Magic (New York: Columbia University Press, 2003).

2 The Travels of Marco Polo (New York: The Orion Press, 1958), 281, 262–266.

3 Two of Xavier’s letters from 1549 can be found in a two-volume compendium of Jesuit correspondence first published in 1598 and recently re-published in a facsimile edition by José Manuel Garcia, Cartas que os Padres e Irmãos da Companhia de Iesus Escreuerão dos Reynos de Iapão & China aos da Mesma Companhia da India & Europa, des do Anno de 1549 Até o de 1580. 2 Vols. (Maia: Castoliva Editora, 1997), I, 7–16; Donald F. Lach, Asia in the Making of Europe, Volume I, Book 2 (University of Chicago Press, 1965), 651–729.

4 Neil McMulin, Buddhism and the State in Sixteenth-Century Japan (Princeton: Princeton University Press, 1984); William W. Farris, Japan’s Medieval Population: Famine, Fertility, and Warfare in a Transformative Age (Honolulu: University of Hawai’i Press, 2006).

5 Japanese sources indicate the first Europeans to reach Japan were Portuguese merchants who were “cast ashore” in 1541. Shin’ichi Tani, “East Asia and Europe.” In Namban Art, A Loan Exhibition from Japanese Collections. International Exhibitions Foundation., eds. Shin’ichi Tania and Sugase Tadashi 13–18 (New York: International Exhibitions Foundation, 1973), 13.

6 As late as 1577 there were only eighteen Jesuits in all of Japan. The number jumped to fifty-five in 1579, and eighty-two in 1583. Cartas … de Iapáo & China, I, 432, II, 89.

7 See Ross, A Vision Betrayed; J.F. Moran, The Japanese and the Jesuits (London: Routledge, 1993); Donald F. Lach, Asia in the Making of Europe, Volume I, Book 2 (University of Chicago Press, 1965), 651–706. C.R. Boxer, The Christian Century in Japan 1549–1650 (Berkeley: University of California Press, 1951); George Elison, Deus Destroyed: The Image of Christianity in Early Modern Japan (Cambridge: Harvard University Press, 1973); Josef F. Schütte, Valignano’s Mission Principles for Japan, 1573–1582, Parts I and II (St. Louis: The Institute of Jesuit Sources, 1980, 1985); Jacques Proust, Europe Through the Prism of Japan (Notre Dame: Notre Dame Press, 2002); Dauril Alden, The Making of an Enterprise, The Society of Jesus in Portugal, Its Empire, and Beyond 1540–1750 (Stanford: Stanford University Press, 1996); Samuel H. Moffett, A History of Christianity In Asia, Volume II, 1500–1900 (Maryknoll, N.Y.: Orbis Books, 2005), 68–105; Ana Fernandes Pinto, “Bibliography of Luso-Japanese Studies.” Bulletin of Portuguese/Japanese Studies 3(2001):129–152.

8 For a discussion of early commentators on Japan see See Rui Manuel Loureiro, “Jesuit Textual Strategies in Japan Between 1549 and 1582.” Bulletin of Portuguese/Japanese Studies (2004) 8:39–631; Lach, Asia in the Making, I, Bk 2, 651–689.

9 Acosta’s Natural and Moral History of the Indies (1590) was based largely on what others had observed and reported, and quite unlike Frois, Acosta emphasized satanic deception as much as reason or free will when reflecting on the customs of Amerindians such as the Mexica or Inca.

10 For the medieval traditions of travel writing and the earliest forms of ethnology, see Margaret Hogden, Early Anthropology in the Sixteenth and Seventeenth Centuries (Philadelphia: University of Pennsylvania Press, 1964); Islam, The Ethics of Travel; Heng, Empire of Magic; Stephen Greenblatt, Marvelous Possessions The Wonder of the New World (Chicago: University Of Chicago Press, 1991).

11 Thus Frois’ rhetoric amounted to more than a “theoretical curiosity.” Greenblatt, Marvelous Possessions, 45–46.

12 Heng, Empire of Magic, 250–51. For a discussion of the contingencies that governed Jesuit missionary perceptions and representations of “others” see Daniel T. Reff, “Critical Introduction.” In History of the Triumphs of Our Holy Faith Amongst the Most Fierce and Barbarous Peoples of the New World, by Andrès Pérez de Ribas, 11–46, eds. D.T. Reff, M. Ahern, and R. Danford (Tucson: University of Arizona Press, 1999).

13 To give but one example, the anua for the year 1582 recounts how the Jesuits’ long-time friend and recent convert, the daimyo Õtomo Yoshishige, invaded nearby Chikuzen, destroying Buddhist temples and the homes of three thousand Buddhist monks. Cartas … de Iapáo & China, II, 25.

14 Real Académia de la História (Jesuitas 11–10–3/21), Madrid, Spain.

15 Josef Franz Schütte, S.J., Kulturgensäte Europa-Japan (1585) (Tokyo: Sophia University, 1955).

16 Englebert Jorißsen, “Exotic and ‘Strange’ Images of Japan in European Texts of the Early 17th Century.” Bulletin of Portuguese Japanese Studies 4 (2002): 37–61; Das Japanbild im “Traktat” (1585) des Luis Frois (Munchen: Aschendorffsche Verlagsbuchhandlung Gmbh & Co., 1998).

17 Frois’ history was not published until the twentieth century, and by then, Part I of the monumental work had been lost. The extant table of contents for the missing volume has chapter titles that are very similar to those in the Tratado. See Luís, Fróis, S.J. Historia de Japam, ed. Jose Wicki, S.J. 5 vols. (Lisbon: Biblioteca Nacional de Lisboa, 1976[1597]), 11–12.

18 Were it not for the fact that João Rodrigues only had been in Japan a relatively short time, one might suspect him to be the author of the Tratado. Rodrigues “the interpreter” would go on to demonstrate a marvelous knack for languages and a profound understanding of Japanese culture. He authored Arte da Lingoa de Japam (1604) and a later (1620) abridged edition (Arte Breve da Lingoa Iapoa). He was no doubt also the chief contributor to the anonymous (“compiled by some fathers and brothers…”) Vocabulario da Lingoa de Iapam (1603). Toward the end of his life, Rodrigues authored a history of the Church in Japan. See Michael Cooper, ed. and trans., This Island of Japon. Tokyo: Kodansha International Limited.

19 Several dozen of Frois’ letters can be found in Cartas … de Iapão & China. See also Joseph Wicki, S.J., ed., Documenta Indica IV (1557–1560) (Rome: Monumenta Historica Soc. Iesu., 1956), 269–305, 643–694; For a list of Frois’ letters see Cartas … de Iapão & China, I, 30–31; G. Schurhammer and E.A. Voretzsch, Die Geschichte Japans (1549–1578) von P. Luis Frois, S.J. (Leipzig: Verlag der Asia Major, 1926), xxviii–xxiii. For an English-language example of one of Frois’ letters from 1565, see Peter C. Mancall, ed., Travel Narratives from the Age of Discovery, An Anthology (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2006), 156–165.

20 While Latin remained the official language of the Church, during the thirteenth century the Portuguese crown made Portuguese the exclusive language of secular government. A.R. Disney, A History of Portugal and the Portuguese Empire (Cambridge” Cambridge University Press, 2009), 95.

21 Luís Adáo de Fonseca. Vasco de Gama; o homem, a viagem, a Epoca (Lisbon: Comissáo de Coordenacáo da Regiáo Alentejo, 1997); Damiáo de. Góis, Lisbon in the Renaissance [Urbis Olisiponis Descriptio], trans. Jeffrey S. Ruth (Ithaca, N.Y.: Ithaca Press, 1996[1554]).

22 Vitorino M. Godinho, Os Descobrimentos E A Economia Mundial. 2 Vols. (Lisbon: Editora Arcádia, 1965), 173–262.

23 José Sebastião da Silva Dias, Os descobrimentos e a problematica cultural do século XVI (Coimbra: University of Coimbra, 1973), 6.

24 After the fight, which never really materialized as the elephant fled, King Manuel sent the rhinoceros to Rome as a gift for Pope Leo X; the rhino died en route but descriptions of it found their way to Dürer, who turned them into his perhaps most famous engraving. Felipe Veiera de Castro, The Pepper Wreck (College Station: Texas A&M Press, 2005), 11; David Johnston, trans., The Boat Plays by Gil Vicente (1997), 8.

25 See Damião de Góis, Lisbon in the Renaissance, 265–26; Nigel Griffin, “Italy, Portugal, and the Early Years of the Society of Jesus.” In Portuguese, Brazilian, and African Studies, eds. T.F. Earle and Nigel Griffin, pp. 133–149 (Warminster, England: Aris & Phillips, 1995).

26 The trials and tribulations of the long voyage to India are powerfully conveyed by Georg Schurhammer, S. J., Francis Xavier, His Life and Times, 4 Vols. (Rome: Jesuit Historical Institute, 1977), II, and Jonathan Spence, The Memory Palace of Matteo Ricci (New York: Viking Penguin, 1984), 76–80.

27 Van Linschoten, the Dutch accountant for the archbishop of Goa, Fonseca, noted that many merchants and colonists in Goa had up to thirty slaves who attended to every need of their mostly Portuguese masters. Arun Saldanha, “The Itineraries of Geography: Jan Huygen van Linschoten’s Itinerario and Dutch Expeditions to the Indian Ocean, 1594–1602.” Annals of the Association of American Geographers:101(2011):149–178, 163. For another contemporary account of Goa, see Guido Gualtieri, Relationi della venuta de gli ambasciatori Giaponesi a Roma, sino alla partita di Lisbona (Venetia: Appresso I Gioliti, 1586), 16–20; Antonio da Silva Rego, História das Missoes do Padroado português do Oriente, vol. 1, India, 1500–1542 (Lisbon: Agencia Geral das Colonias divisao de Publicacoes e Biblioteca, 1949).

28 John W. O’Malley, The First Jesuits (Cambridge: Harvard University Press, 1993), 37–50.

29 By the time Frois wrote the Tratado, the Jesuit order was essentially redefining itself as a teaching rather than missionary order.

30 When individuals enter the Jesuit order they undergo training for either the priesthood (spiritual coadjutors) or as “brothers” (temporal coadjutors). Scholastics are those pursuing the first “track,” which can lead to yet more academic training and the highest rank of the Jesuit order, the “professed.” See O’Malley, The First Jesuits, 345–347.

31 A catalogue drawn up in 1559 by Frois’ Jesuit superior, P. G. da Siveira, describes Frois as “of slight build, humane spirit, well-intentioned, and naturally discreet. In time he will benefit by becoming a coadjutor having taken three vows.” Joseph Wicki, S.J., Documenta Indica IV (1557–1560) (Rome: Monumenta Historica Soc. Iesu, 1956), 472.

32 See, for example, Frois’ lengthy letters for 1559 and 1560 in Wicki, Documenta Indica IV, 269–305, 643–694.

33 Cartas … de Iapão & China, I, 22. The Jesuits’ racist attitude toward people of color, who were cast as inherently inferior to whites and thus suitable as slaves, is made explicit in colloquy #5 of De Missione Legatorum Iaponensium ad Romanam Curia (Macao, 1590), which was largely authored by Valignano. See also Schütte, Valignano’s Mission Principles, I, PI, 130–131; Alonso de Sandoval, Treatise on Slavery, Selections from De instauranda Aethiopum salute, ed. and trans. Nicole von Germeten (Indianapolis: Hackett Publishing, 2008).

34 The Goa mission was plagued by poor leadership and declining morale during the decade Frois spent in the city. Apparently many Jesuits besides Frois wanted out of Goa, as the Jesuit Father General, Lainez, found it necessary in 1560 to require that they remain at their posts. Donald F. Lach, Asia in the Making of Europe, Volume I, Book 1 (University of Chicago Press, 1965), 252–253.

35 Jurgis Elisonas, “Christianity and the Daimyo,” In The Cambridge History of Japan, Volume 4, Early Modern Japan, ed. John W. Hall, 301–372 (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1991), 318–320.

36 In the anua of 1579 it was noted that there were scarcely 2,000 Christians in all of Bungo and the vast majority were the poor and sick who came to be cured at de Almeida’s hospital. Cartas … de Iapão & China I, 436,

37 Ibid., 145–151.

38 In 1571 Nobunaga’s patience seemingly ran out and he laid siege to Mt. Hiei, attacking and destroying the monastery of Enryaku-ji and killing several thousand men, women and children.

39 Elisonas, “Christianity and the Daimyo,” 63, 75–76.

40 In letters reproduced in a Jesuit volume from 1575, Frois mentions long conversations he had with Nobunaga and how the Japanese ruler personally escorted him around Gifu and Azuchi castles. Cartas que los padres y hermanos de la Compañia de Iesus que andan en los Reynos de Iapon escriuieron alos dela misma Compañia (Alcala: En casa de Iuan Iñiguez de Lequerica, 1575), 287–294.

41 Frois was assigned this task after Claudio Acquaviva, the fifth father general of the Jesuit order (1581–1615), instructed Jesuit provinces around the world to select a member to compile letters and other documents and write a history of each Jesuit province. Frois’ primary responsibility of writing his Historia was interrupted on occasion by stints as socius or secretary/assistant to the Jesuit vice provincial in Japan as well as the father visitor, Valignano. Also, from 1592–1595 Frois was in Macao as Valignano’s assistant.

42 Not only does the table of contents for the lost book parallel the chapters of the Tratado, but the latter begins with a dedication to “Jesus [&] Mary,” which is how Frois also began at least some of his letters. See, for instance, Cartas … de Iapáo & China, I, 416.

43 Schütte, Kulturgegensätze, 94–95; Lach, Asia in the Making, I, 2, 686–687; J.F.Moran, The Japanese and the Jesuits, Alessandro Valignano in Sixteenth-Century Japan (London and New York: Routledge, 1993), 153.

44 In his Summary of Japan, written in 1582–83, Valignano repeats many of the contrasts that show up in the Tratado. Sumario de Las Cosas de Japon (1583), Adiciones del Sumario de Japon (1592), ed. José Luis Alvarez-Taladriz (Tokyo: Sophia University, 1954). See also Valignano’s Historia del Principio y Progresso de la Compañia de Jesus en las Indias Orientales, ed. Josef Wicki, S.J. (Rome: Jesuit Historical Institute, 1944), 136–162. One can well imagine that the contrasts were suggested or elaborated on by Frois while serving as Valignano’s “guide.” This possibility is further suggested by the first paragraph from the title page of the Tratado, which rhetorically, at least, speaks of more than one author (i.e. “In order to avoid confusing certain matters with others, we [emphasis ours] divide this work…”). See also Schutte, Valignano’s Mission Principles, I, Pt. I, 285–289.

45 See Valignano’s letter to Father General in Rome, in Moran, Japanese and the Jesuits, 35. See also Schütte, Valignano’s Mission Principles, I, Pt. I, 270–271; M. Antoni Ücerler, S.J., “Alessandro Valignano: man, missionary, and writer.” In Asian Travel in the Renaissance, ed. Daniel Carey (London: Blackwell Publishing, 2004), 12–42.

46 As Elisonas points out, while the Japanese were blamed for this piracy, most of the pirates were actually Chinese. Jurgis Elisonas, “The inseparable trinity: Japan’s relations with China and Korea,” In The Cambridge History of Japan, Volume 4, Early Modern Japan, ed. John W. Hall, 235–301 (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1991), 250.

47 Before China prohibited trade with Japan, Chinese fleets with upwards of two hundred ships put into Japanese ports each May, trading silk for silver. Yoshitomo Okamoto, The Namban Art of Japan (New York: Weatherhill, 1972), 12.

48 L.M. Cullen, A History of Japan, 1582–1914 (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2003), 18–62.

49 This mercantile involvement was in clear violation of Church rules, but it was defended by Valignano on the grounds that there was simply no other source of revenue to support the Japan mission.

50 Prior to circa 1574, there were relatively few Jesuits in Japan and only a few such as Frois and Vilela knew Japanese. The Jesuits on the whole relied heavily on Japanese assistants called irmao and dojuku, who often lived in or near Jesuit residences and did much of the actual preaching and work of converting fellow Japanese. See Ross, Vision Betrayed, 49–51.

51 Arguably the monks’ opposition to the Jesuits was precipitated by the violent destruction of Buddhist temples by prominent daimyo (e.g. Omura Sumitada in Bungo in 1563) who converted to Christianity.

52 Daniel T. Reff, Disease, Depopulation, and Culture Change in Northwestern New Spain, 1518–1764 (Salt Lake City: University of Utah Press); Plagues, Priests, and Demons (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2005).

53 The Japanese had a long history of exposure to Old World diseases (and thus acquired resistance to) maladies that devastated Amerindians. Ann Bowman Janetta, The Vaccinators, Smallpox, Medical Knowledge, and the “Opening” of Japan (Stanford: Stanford University Press, 2007). See also Linda Newson, Conquest and Pestilence in the Early Spanish Philippines (Honolulu: University of Hawai’i Press, 2009), 17–18.

54 McMulin, Buddhism and the State in Sixteenth-Century Japan.

55 Ibid. See also Moran, The Japanese and the Jesuits, 70; Murdoch, History of Japan, II, P.I, 164.

56 Michael Cooper, They Came to Japan, An Anthology of European Reports on Japan, 1543–1640 (Ann Arbor: University of Michigan Press, 1999[1965]), 42.

57 Schütte, Valignano’s Mission Principles, I, Pt 1, 251–260; Ross, A Vision Betrayed.

58 Ross, Vision Betrayed, 59, points out that this realization arose after Valignano visited the Honshu missions founded by Vilela and Frois and run by Organtino, all of whom had acquired an intimate knowledge of Japanese language and culture.

59 The “way of tea” took definitive shape in the sixteenth century. Dennis Hirota, Wind in the Pines, Classic Writings of the Way of Tea as a Buddhist Path (Fremont, California: Asian Humanities Press, 1995).

60 Ross, A Vision Betrayed, 72. See also J.M. Kitagawa, Religion in Japanese History (New York: Columbia University Press, 1966).

61 Because the Japanese considered Europeans barbarians, Valignano also wanted to impress the four young Japanese with the wealth, power, and grandeur of the Catholic Church and Europe’s ruling families. Cartas … de Iapáo & China, II, 89.

62 Frois devoted a whole section of his Historia to a detailed account of the ambassadors’ trip to Europe. See J.A. Abranches Pinto, Yoshitomo Okamoto, and Henri Bernard, S.J., eds. La Premiere Ambassade du Japon en Europe. Monumenta Nipponica Monographs 6. (Tokyo: Sophia University, 1942). See also: Guido Gualtieri, Relationi della venuta de gli ambasciatori Giaponesi a Roma; Luis de Guzman, Historia de las Misiones de la Compañía de Jesus en La India Oriental, en la China y Japon desde 1540 hasta 1600 (Bilbao: El Mensajero del Corazon de Jesus, 1891[1601]), 422–458; Judith C. Brown, “Courtiers and Christians: The First Japanese Emissaries to Europe.” Renaissance Quarterly 47 (1994): 872–906; Michael Cooper, The Japanese Mission to Europe, 1582–1590 (Kent UK: Global Oriental, 2005), 169–170; Christina H. Lee, “The Perception of the Japanese in Early Modern Spain: Not Quite ‘The Best People Yet Discovered,” eHumanista 11(2008):345–381. One or more of the Japanese teenagers purportedly kept diaries of their trip to Europe, which Valignano re-worked into the thirty-four dialogues that make up De Missione Legatorum Iaponen, trans. Duarte de Sande (Macao 1590).

63 Schütte, Valignano’s Mission Principles, I, Pt. II.

64 Valignano, Sumario de Las Cosas de Japon, 242; see also Schütte, Valignano’s Mission Principles, 1 Pt. II, 242–243.

65 This offering of tea to a guest in a receiving room is different from the more formal “tea ceremony,” which usually entailed several men sharing tea (“ritually” prepared and served by the host) in a room or primitively-styled hut, set in a garden. The earliest definitive study of chanoyu remains Juan Rodriguez’s Arte del Cha, ed. J.L. Alvarez-Taladriz. Monumenta Nipponica Monographs 14 (Tokyo: Sophia University, [1620]1954).

66 Wind in the Pines, 44.

67 Antônio Houaiss, Mauro de Salles Villar, and Francisco Manoel de Mello Franco, eds., Dicionário Houaiss da língua portuguesa (Rio de Janiero: Objetiva, 2001), 2756–7.

68 Historia de Japam, Vol. I.

69 The thought-provoking use of contradiction is also characteristic of popular texts such as the Libro de buen amor (1330) and Chaucer’s The Canterbury Tales (1380) (e.g. “The Wife of Bath” tale that articulates but then demolishes the case for gender equality).

70 Constance Brittain Bouchard, Every Valley Shall Be Exalted, The Discourse of Opposites in Twelfth-Century Opposites (Ithaca: Cornell University Press, 2003); Catherine Brown, Contrary Things, Exegesis, Dialectic, and the Poetics of Didacticism (Stanford: Stanford University Press, 1998).

71 Ronald E. Pepin, An English Translation of Auctores Octo, a Medieval Reader (Lewiston, N.Y.: Edwin Mellen Press, 1999); “The Distichs of Cato, A Famous Medieval Textbook,” trans. Wayland Johnson Chase. The University of Wisconsin Studies in the Social Sciences and History, Number 7 (1922).