chapter 3

The Praxis of Honor

Muscovites of all social ranks litigated energetically to defend their honor. The courts served them because it was a traditional responsibility of a good tsar to provide justice. The community played a role in honor disputes, because insult to honor disturbed community stability and because community involvement was integral to the legal process in Muscovy, as it was in many other premodern judicial systems. Thus, the ways in which people litigated over insult are expressions of the broader legal culture. Trials over dishonor can serve as a case study of the Muscovite legal system and as a window into how communities and individuals pursued and resolved disputes. This chapter, then, explores several aspects of Muscovite legal culture by examining how honor fit into individuals’ and communities’ strategies of dispute resolution.

Discovering why people litigate in premodern societies, particularly over something as intangible as insult and reputation, is not as straightforward as it might seem. Because their goals in litigating rarely involved “a disinterested love for the law”1 or a desire to enforce objective norms, disputants litigated in ways that we might not expect. Litigants very frequently, for example, did not pursue cases to conclusion, or they accepted the judgment of God in coming to resolution. They frequently settled even seemingly rock-solid cases out of court. They often invoked the authority of the community in the form of witnesses, sureties, or character references in pursuing their suits. They accepted and made use of the social, theatrical, and ritual aspects that are embedded in trial processes. Such attitudes and practices made for a legal culture of remarkable flexibility and responsiveness in early modern Russia.

Circumstances of Insult and Violence

Litigation is the culmination of stress between individuals or groups, often against the backdrop of broader community tensions. Litigations over insult in particular silhouette people at a moment of crisis and show in stark relief the social system within which people live and the means they use to pursue and resolve disputes. Such litigations also highlight violence and its containment and raise the question of the level of violence in Muscovy. Most insults arose between people who were acquainted with each other. Horace W. Dewey, working with a small sample of litigations, argued that most dishonor litigations occurred between individuals of the same social rank.2 The database used here confirms his conclusion. In 566 cases in which the social situation of litigants can be ascertained, almost two-thirds (382 cases) occurred among social equals. Less often did social superiors sue inferiors (115 instances in 566 cases), and only infrequently did social inferiors sue superiors (69 of 566 cases).3 These statistics indicate that insults were a common byproduct of community interrelations and, further, as I shall argue in this chapter, that litigation over insult itself constituted a means of social interaction in communities. It could promote social stability or it could further disrupt it, and whether the goal was restorative or disruptive, in either case it was accomplished by willful execution of a shared discourse of community norms.

Least often in this collection of cases did insult arise among strangers encountering each other in public places. This did occur, however. Marketplaces seem to have been rife with idle insult, seemingly unprovoked, among strangers. For example, a priest of the Kholmogory diocese complained in 1579 of being insulted and assaulted by a man attempting to steal his money at market. Eleven years later, the same priest sued again for assault and dishonor on the road outside a tavern.4 In 1687, a servant of the Siberian tsarevich Vasilii Alekseevich complained of being insulted without provocation in the marketplace by strangers.5

Insults often punctuated the pursuit of official duties. Military men were known to denigrate their superior officers. In 1594, for example, a Cossack commander complained that his hundredman had disobeyed him, shot and assaulted people while drunk, and insulted the commander when he began an investigation into the man’s misbehavior.6 Townsmen sometimes refused the orders of the public safety and fire warden (ob’ezzhii). A warden in 1671 reprimanded a resident of Moscow for keeping his fire burning at night and in return suffered a hail of insults about himself, his father, and his mother.7 Civil and military officials sometimes quarreled over jurisdiction and authority. In the 1520s, for example, a military commander accused his colleague of insubordination and insult in a dispute over lines of command. In 1636, two military commanders in Krapivna on the southern frontier accused each other of insult and insubordination. In 1687, disputants came to blows and insults when a judge accused the state secretary assigned to his court of improperly registering documents at his home, not in the chancery as required. They settled the dispute after the plaintiff won a judgment based on witness testimony.8

Governors and elected local officials were often insulted in the line of duty. In 1626, for example, an elected judicial official in the far northern Kholmogory region served notice on a local peasant that he should divide his land based on a recent sale. Instead, the peasant seized the deed from him, insulted and assaulted him, and stole his bag with other official documents in it. In 1644, a locally selected criminal officer (gubnoi starosta) repeatedly refused requests by the governor of Voronezh to help in investigations, once insulting him by calling him a “penny farthing little governor” (grivnenyi voevodishka).9 Conversely, others sued for excess brutality and insult at the hands of officials, as in 1627, when a peasant in Ustiug Velikii sued the local customs and alcohol chief for assault and insult relating to a dispute over a shipment of rye. And in 1633, the archbishop of Astrakhan’ and the Terek region sued the governor of nearby Chernoiarsk for theft, assault, dereliction of duty, and insult to his various officials.10

As common as these complaints were, the vast majority of dishonor cases occurred between private individuals in day-to-day, unofficial interaction. As we saw in Chapter 2, kinsmen frequently accused each other of insult. Parents accused children of disrespect, fathers-in-law sued daughters-in-law and vice versa for disobedience and abuse, in-laws came to insults over disputed in heritances. Even more commonly in the records, neighbors fell into disputes. Banquets and weddings were classic occasions for insults to flare: Tongues were loosened by drink, and the gathering often brought together individuals who would not otherwise associate. Not surprisingly, early Rus’ and Muscovite law codes defined specific punishments for affronts to guests at ceremonial occasions.11 Examples of brawls at these occasions abound in the cases in the database. Two gentrymen, for example, fell to brawling at a wedding in Lebedian’ (south of Moscow, on the upper Don River) in 1629; two Europeans (Anthony Thomson and J. Edward Rowland) at a Christmas party in 1646 fell to blows and insult in a long-simmering dispute over a debt; and in 1649, two monastic servitors who had been at a banquet got into a quarrel on the way home.12

Whereas insults at festive occasions seem to have arisen spontaneously, many others arose among neighbors in the context of property disputes or neighborhood tensions. In dishonor litigations, one can glimpse the petty quarrels that punctuated life in small communities, be they villages, military regiments, or the exclusive elite that assembled daily in Kremlin anterooms. Numerous litigants describe being harassed and insulted by their neighbors until they were driven from their villages. In 1635, for example, a family in Shuia in the Vladimir area allegedly so harassed its neighbors with insults, threats of assault, and stone-throwing that the neighbors filed a notice against them. In a similar case of 1619, also in Shuia, a man complained of his neighbors: “We cannot walk past their house, they sic their dogs on us, and when we try to defend ourselves they try to cut us with a knife, and they brag that they will murder us. Because of all this threat and attacks by dogs and humiliation and insult from him and his sons, I, my mother, and wife are unable to live.”13 In a rural setting in the North in 1605, a family left the village because of a neighbor’s persistent sexual slander of its women. Similarly, a peasant complained in 1606 that his neighbor harassed him, telling him “You cannot flee from us, we’ll have your head, you won’t be able to live in this village with us.”14

Close quarters among strangers also bred strife. A townsman on the southern frontier complained in 1696 of seven Don Cossacks who had been billeted in a cottage at his home. From their window they had shot the plaintiff’s dog and then assaulted the plaintiff when he complained. A nun complained of abuse intended to drive her from the convent.15 Muscovites complained frequently of large-scale assaults on their homes by neighbors, assaults that often included sexual slander and affront to the women of the targeted household. For example, a gentryman of Kashira complained in 1641 that his neighbor with his men rode up to him and his wife while they were working in the fields and set their dogs on them, attacked them, and ordered the wife to bow down in subservience to them.16

It often took some time before individuals went to court; repeated incidents and escalating quarrels might erupt in a final insult or assault that generated a suit. Countless plaintiffs sued over assaults—on their homes, their hayfields, or their property—that were accompanied by abusive language; they often explicitly linked those affronts to long-term disputes over the property in question. For example, two peasants in the Kholmogory area in 1627 disputed a hay meadow and fell to quarreling and insulting each other. The plaintiff alleged, “and in the past they have bragged of all manner of evil things against me and my son and my cattle, of murder and of expelling me from my home.” The defendant responded in kind, saying that the plaintiff had illegally claimed the land for seven years and had repeatedly insulted and threatened him; the defendant even implied that the plaintiff was working witchcraft against him and his family. In another case, an infantryman on the southern frontier complained in 1692 that he was insulted when the men of a local landholder attacked and ransacked his home, accusing him of being a serf and thus ineligible to own property. His soldier status was affirmed by investigation in record books, thus confirming his right to own property.17

A good example of how neighborly relations could boil over into litigation after repeated incidents comes from 1649, when a gentryman on the southern frontier in Userda accused a neighbor of beating and insulting him, his wife, and daughters at his home. In response, the neighbor, also a gentryman, accused the plaintiff of refusing to repay money he had borrowed from the defendant’s mother, accused the plaintiff’s wife of not repaying grain she had borrowed from the defendant’s nephew, and accused the plaintiff of refusing to pay for a sword that he had borrowed and for reneging on other debts. The plaintiff responded by suing the defendant’s widowed mother for not returning dyes she had borrowed from him or the dyed cloth. When the defendant at the trial denied all on his mother’s behalf, the plaintiff accused him of trampling on his grainfields. Faced with taking an oath to the truth of these various allegations, the two acrimonious neighbors settled and split the court fees.18

Verbal insults often served as the last straw in a bitter rivalry. In 1641, for example, two brothers, gentrymen from Kozlov on the steppe frontier, sued a fellow gentryman for dishonor and cited a pattern of harassment by him and his colleagues: “He hates us because of our income and service land grant (pomest’e), wanting to take them forcibly from us.” A groom in the tsar’s stables alleged in 1636 that an artisan in Moscow had approached him and insulted him and his mother because he was angry at a suit the plaintiff had filed against him.19 Some defendants even charged that they had been insulted as part of enduring vendettas. In 1633, for example, a gentryman sued another for assaulting (with his kinsmen) him, his mother, and his wife at a wedding in order to avenge a long enmity with the plaintiff’s son-in-law. In 1653, two gentrymen of Lebedian’ on the southern frontier fell into a sword fight on the road because of a three-year-old quarrel over rights to a meadow and use of common herd land. In 1653, two gentrymen of Efremov sued each other for assault and insult, one calling the other a slave. At trial, one gentryman explained that they had had a dispute about trampled grain for three years and complained that the other had assaulted his lands repeatedly.20

Litigations also reveal the broader networks that structured communities, such as cliques, clans, and patronage networks.21 In a petition of 1628, a peasant sued another peasant, calling him a “powerful (sil’nyi) man,” who with his men had broken into the plaintiff’s home, assaulted him, his wife, and his children and had torn clothing and jewelry off of his wife and daughter. He also allegedly stole a keg of beer that the plaintiff had prepared for his son’s wedding. “In the past they bragged of assaulting and stealing from me, of making false accusations against me and libel and all manner of evil things,” complained the plaintiff. In another case, a peasant petitioned in 1634 against a neighbor who had tried to kidnap one of his servants. Alleging that “He has previously bragged of doing evil things to me such as attacking my home and falsely accusing me and libel and murder,” the plaintiff underscored his lack of powerful allies by calling himself “a solitary little man alone in the world (chelovechenko odinashno), I farm this little plot (pashnishko) alone.” This image of patronage networks is vividly expressed in a 1618 suit in which the Shuia governor requested that a suit over assault and insult among factions of Shuia townspeople be judged in Moscow, not locally, because the faction leaders cannot be sued fairly in the local courts because “they are powerful (oni sil’ny).”22

Local community groups do not figure only negatively in honor disputes; they often act as potential or active allies. A man in 1688 defended himself by saying that if he had really quarreled with the plaintiff as alleged, she would have reported it to the neighbors. In 1689, a woman of Ustiug Velikii accused a priest’s son of raping her niece; he responded by naming his neighbors as character witnesses, saying “My neighbors know that I have never gone out for such knavery (plutovstvo).”23 Neighbors and friends frequently leaped to the rescue of victims of assault and insult, often getting embroiled in the dispute themselves. In a 1638 case, neighbors saved a servant girl from assault. In another case, a man and his servants escaped assault by a gang in the streets of Moscow in 1668 by dashing into the home of a Cossack commander. A neighbor and his men then ran over to protect them, but one of the servants nevertheless was “beaten half-dead.” And in 1695, a monastic servant sued his neighbor because his family was being drawn into the neighbor’s abuse of his wife. She had fled her husband’s beatings to the monastic servant’s home, and now the defendant was allegedly threatening them as well.24

This evidence brings us to a level of lived experience that is rare in Muscovite documents. We hear the firsthand testimony of litigants and witnesses; we see neighbors quarreling and communities leaping into the fray. Neither the personal acquaintanceships nor the violence at the heart of these disputes should be surprising. Neighbors quarreled and litigated because it is precisely among acquaintances that tensions develop in day-to-day interaction and that reputation is most socially important. Sociologists have theorized this; for example, F. G. Bailey writes, “Those nearest are also those with whom you interact most frequently and therefore those with whom you are most likely to have a cause for contention…competition takes place mainly between those who are in the same league.”25 Historians have observed it. Martin Ingram notes that 80% of defamation cases he examined in sixteenth- and seventeenth-century Wiltshire involved people from the same parish: “Slander actions…were characteristically the product of tensions between neighbours of medium substance living cheek by jowl in the small scale communities which made up the fabric of early modern English society.”26 More was at stake than simply erasing slander from the public memory; individuals litigated to advance their social esteem as well. David Garrioch writes, regarding eighteenth-century Paris, that “Many disputes were ultimately struggles for recognition and respect from other members of the local community.”27 These considerations clearly came to bear in Muscovite society, where urban and rural communities organized collectively for administrative and some judicial purposes, where agrarian practice demanded collective cooperation, and where lineage and heritage structured hierarchy in the elite. Valerie Kivelson, for example, analyzed the frequency with which witchcraft accusations sprang up within families at points of tension (e.g., disputes over inheritance, in-law tensions).28 In such settings, tensions easily could compound at the same time that social pressure to maintain a respectable status in the community was constant.

The brawling and disorder exhibited in these cases looks less startling when placed in a comparative context. Faced with similar data, historians of medieval and early modern Europe have been confronting the problem of violence. Admitting the high level of violence that premodern European societies countenanced, they historicize it by exploring its social meaning. Wendy Davies and Paul Fouracre, for example, see violence as social strategy in medieval Europe. It was tempered by societal pressure for restoring peace, but they caution that “We must not idealize the notion of peace. Disputes were in themselves sufficiently common to constitute in themselves part of normal social interaction; ‘peace,’ that is to say, was already pretty contentious.”29 A similar debate about social stability in early modern England postulates a long-term decline in public violence from medieval to early modern times.30

Philippa Maddern extends the concept of violence as social praxis by examining the use of officially sanctioned violence in fifteenth-century England. She argues that violence could be socially stabilizing, because contemporaries distinguished between just and unjust violence. Inappropriate violence transgressed community standards: police brutality, women beating men, riots by the poor against the rich, or wanton rampaging by an unbridled gentry. Violence that was just—drawing legitimacy from analogy to God’s just punishment of sinners—included men’s chastisement of women and servants, the king’s execution of criminals, and a knight’s crusade against the infidel. Maddern argues that violence was not necessarily “reprehensible chaos, but the normal upholder of secure, lawful, hierarchical, godly order…Violence, in short, was a language of social order.”31

Violence involving insult and assault in Muscovy can be similarly contextualized. The violence of the state’s legal sanctions was “just,” and that observed among neighbors and co-workers was a normal result of the stress of life in small communities. Such violence was not a measure of barbarism. Even contemporary European travelers, who reveled in relating the crudity of Muscovite manners, did not report excessive levels of popular violence. The Englishman Giles Fletcher in the late sixteenth century emphasized not violence but the people’s oppressed and servile state, attributing it to abuses by officials and heavy taxation. Jacques Margeret in the early seventeenth century similarly noted that men did not carry weapons except when at war, that dueling and private vengeance were harshly punished, and that people used the courts for recourse from insult. Adam Olearius, traveling in the midseventeenth century, remarked that Muscovites love swearing and quarreling but “very rarely come to blows.” Augustin von Mayerberg in the late seventeenth century attributed violence by slaves to poverty and hunger.32 In modern scholarship, Richard Hellie attributes Muscovite violence to various physiological and social causes.33 The violence we see in dishonor litigations should not be condemned as a Russian moral failing but rather analyzed for what it reveals about social tensions and social interaction.

The Setting of Litigation: Ritual and Community

Individuals and communities devise many ways to resolve conflict. Third-party judicial institutions are not essential; conflict resolution can be structured by personal motivations such as “moral obligations and the persuasion of peers,” in Georges Duby’s phrase. It could be pursued with strategies ranging from bilateral negotiation to the intercession of mediators to feud or ordeal.34 Current scholarship avoids a strict delineation between “stateless societies” that depend on such informal means and bureaucratically organized judicial systems, seeing instead private mechanisms of dispute resolution permeating formalized judicial processes—as we indeed see in Muscovy. Nevertheless, the structuring organization for dispute resolution in Muscovy was a “triadic” judicial institution overseen by the grand prince and his judges. Those structures developed for much the same time-honored reasons that justified the extension of princely or ecclesiastical power over private disputes in premodern Europe.

The Muscovite state provided access to litigation over personal honor not only because it proved lucrative in court fees and asserted central control over political rivals. Perhaps most important, grand princes, like European kings, played the role of judge because it was one of the oldest and most traditional expectations of rulers in the Christian tradition. In Muscovite panegyrics to good rulers, the duty of rendering justice and the restraining power of “law” on the tsar’s power are central themes. By “law,” authors meant more than written codes, including Christian ethics and tradition as well. Learned authors saw justice as key to social stability and urged rulers to establish a worldly administration that was just and fair. Good rulers were expected to supervise their officials to avoid corruption and abuse of the people. A fourteenth-century source linked good justice with a ruler’s piety:

Having been gods, you will die as men and will be sent to a dog’s place, to hell…. And you in your place appoint as governors and lieutenants men who are not fighters for God, pagans, perfidious, who do not understand judging and do not consider justice, who adjudicate while drunk, who hasten the proceedings…. People cry to you, O prince, and you do not avenge them…. Under an unrighteous tsar, all the servants under him are lawless.35

Similar thoughts were expressed in the early sixteenth century by a secular author, the diplomat Fedor Karpov. Reflecting not theocratic ideas of God-given authority, but rather citing Aristotle, Karpov argued that societies require firm government based on justice and laws: “Social order in cities and states will perish from soulful long enduring; long-suffering in people without justice and law destroys the welfare of society and social order is debased completely; evil morals arise in states and people become disobedient to rulers because of their depraved condition.”36 Maksim Grek, a Greek transplanted to Russia, declared in the early sixteenth century that the good ruler was guided by God’s law, whereas the tyrant despises the word of God, the teachings of the church, and the advice of good men.37 The quasi-literary depiction of Ivan IV at the 1551 church council, included in the protocols of the council known as the “Stoglav,” again links justice with piety:

Having filled yourselves with the spiritual profits of Holy Scripture, instruct me, your son; enlighten me in every sort of piety. For it is good for the tsar to be pious, for all the laws of the tsar to be just and for him [to live] completely in the true belief and in purity.38

As well, the theme of the law is paramount in writings attributed to Ivan Peresvetov, a publicist of the midsixteenth century: “[God aids him] who calls on God for help and who loves justice and maintains a just court: justice is the heartfelt joy of God and the great wisdom of the tsar.”39

Historical tales written in the first one-third or so of the seventeenth century about the national catastrophe known as the “Smuta” or “Time of Troubles” affirmed the responsibility of the good ruler to heed God’s rules.40 The tales’ conservatism was echoed in the church schism that erupted in the 1660s; Archpriest Avvakum advised Tsar Aleksei Mikhailovich that “The honor of the tsardom is to love justice.”41 These ideas, didactic as they were, identified the crucial significance of a well-run judicial system: Justice for the people enhanced social stability because people had peaceable means to resolve conflict. These ideals represent the loftiest goals and perceptions of Moscow’s judicial enterprise.

Few judicial systems, however, meet such high expectations, and Muscovy’s was no exception. Other sources suggest a necessary corrective. Horace Dewey argued forcefully that the most pressing reason that the state issued the 1497 and 1550 law codes and charters of local government was to curb corruption by governors and judges.42 The introduction of local administrative reforms in the 1530s is similarly linked to corrupt, ineffective local government.43 Valerie Kivelson and others have chronicled the avalanche of seventeenth-century gentrymen’s complaints against local power networks (sil’nye liudi), particularly as they corrupted the judicial process.44 The first generation of recorded secular tales, in the late seventeenth and early eighteenth century, included satires on the corruption of the court system. The Tale of Ersh Ershovich, for example, is a dead-on parody of a trial transcript, complete with formulaic language and proper procedure, except that the judges and litigants are all fish! Shemiaka’s Judgment depicts judges as infinitely corruptible, litigants as cunning and devious, and the process as flawed. And Muscovy’s most famous “rogue,” Frol Skobeev, one should remember, was said to be a solicitor of litigations.45 Certainly the corruption and red tape of the courts in Imperial Russia was infamous: John LeDonne described the “nightmare” of eighteenth-century litigation, with increasing and overlapping layers of courts of appeal and unclear norms of procedure, and Denis Fonvizin’s satirical plays lampooned corrupt judges. Irina Reyfman argued that by the turn of the nineteenth century, noblemen turned to dueling out of complete disaffection with the judicial process.46

It is important, however, not to read the malaise of the modern Russian bureaucracy back into the pre-Petrine period or to take either idealized extreme at face value. The Muscovite court system had its share of corruption; the central government was aware of it and could react quickly to explicit complaints of judges’ conflicts of interest.47 The minimalism of the Center’s local control, however, typically left communities at the mercy of their officials. Even so, recent scholarship has problematized the issue of judicial corruption, arguing that bribery was a reciprocal relationship and that patronage and favoritism were traditional means of governance. What moderns condemn as corruption was not viewed so pejoratively in Muscovy until it reached extremes.48 Potential litigants had a touching, if naive, faith in the potential of the system to serve them. Kivelson presents seventeenth-century gentrymen as committed to the perfectibility of the system even in the face of abuse: “You [Sovereign] should…order all dishonest judges to be rooted out…and in their place to be chosen just people, who would be able to answer for their judgments and for their service before God and before your tsarist majesty.”49 Clearly provincial gentrymen in their petitions hoped that the system could work. The evidence of dishonor litigations, as well as of other monographic studies of seventeenth-century legal culture,50 shows a populace unwilling to disengage, as Reyfman’s alienated noblemen did. People seemingly regarded the judicial system as worth the risks of litigation.

Going to court over honor and reputation, after all, posed risks. It advertised the details of an insult, for example, perhaps setting them in the community memory; it risked the plaintiff’s being further insulted in the course of the trial or losing the trial; it gave the insulter an arena in which potentially to win public opinion over to his side; it took the disputants away from field, service, or trade; and, perhaps most of all, it was costly.51 Court fees in Muscovy in the midseventeenth century, for example, could amount to about one-third of a ruble per ruble value of the suit. Even though some social groups (musketeers, hetmans) were excused from some of these fees,52 the burden could be considerable. In 1640, for example, a gentryman settled a case, agreeing to pay court fees of more than eight rubles, a significant proportion of his forty-ruble annual cash grant. Another gentryman lost a suit in 1641 and found himself liable for forty-seven rubles in dishonor fines plus five rubles in court fees, when his annual cash grant was probably only in the fifteen- to twenty-ruble range.53 In 1685, a townsman of Kolomna, whose own dishonor value was no greater than seven rubles, was to pay between three and four rubles in court fees plus a twenty-eight-ruble fine.54 In the seventeenth century—to cite representative values—prices remained relatively stable. For horses, prices ranged from one to five rubles; annual rent for peasants ranged from one-twentieth of a ruble to two-and-a-half rubles a year. Skilled craftsmen may have earned twenty rubles a year.55 By these standards, fines and court fees could be burdensome.

Yet people did litigate: In my database, individuals as diverse as great boyars, Siberian Cossacks, and indentured servants went to court. That they did so suggests that plaintiffs and defendants believed that the judicial process could satisfy their goals. Some went to court because a privately pursued vendetta was not a viable option; taking the law into one’s hands was harshly punished in Muscovy. But most had more pragmatic goals. They understood that honor was a tangible possession that should be protected, lest the insult lower their public standing, imperil their marriage chances, or cost them in material terms. A tradesman accused of dishonesty, for example, would justly fear loss of business. Although some plaintiffs might sue solely to harass and publicly humiliate their rivals, most wanted speedy settlement and material compensation.

When litigants approached the court, they found a well-articulated judicial system. It is difficult to make comparisons to other systems. It is likely that Muscovy’s court system was less bureaucratically developed than, for example, contemporary English courts. Muscovy’s obsession with preserving every scrap of paper associated with a suit is testimony to a less sophisticated bureaucracy. There was no formal code of judicial procedure, even by the eighteenth century, as John LeDonne remarked.56 There was, however, a simple hierarchy for appeals, a fairly straightforward process, effective centralization of procedures, and wide dissemination to local chancery offices of manuals of procedure (ukaznye knigi), culminating in the 1649 Conciliar Law Code, which devoted its longest chapter (chapter 10) to that topic. By early modern standards, this was a functioning, if not fully rational, judicial system.

Suits for dishonor were initiated by the aggrieved party, and the litigants had broad leeway in deciding how far and in what ways the trial progressed.57 Litigation began with the filing of a petition, generally in written form, but sometimes delivered orally and followed by a written petition.58 Petitions were filed with the relevant judicial body: in the Center and frontier, with the governors (voevody); in Moscow, for landed military servitors, with the various judicial chanceries (Moskovskii and Vladimirskii sudnye prikazy); for taxed citizens in Moscow, with the Zemskii prikaz; for workers in various chanceries, with the chancery (prikaz) itself (the Armory, for example); for foreigners, with various chanceries for foreigners; and in the North, with local communal officers, governors, or even cathedrals or monasteries, depending on local circumstances. Muscovy made no firm distinction between civil and criminal suits, and it used two kinds of legal procedure—the accusatory (sud) and the investigatory (sysk, rozysk) processes—sometimes interchangeably. The accusatory procedure was initiated by litigants and could be settled before judgment. In it, the judge functions as a mediator between sides, who present their own arguments and witnesses. Investigatory suits, by contrast, can be initiated by either litigants or state authorities and cannot be settled before judgment. In these suits, the judge plays the role of active investigator, aggressively seeking out evidence, initially by deposition of the accused and then by various types of inquiry, including the community inquest (poval’nyi obysk), which was a survey of a large body of witnesses in the community where the crime occurred. Over time, accusatory suits absorbed some of the procedures of investigatory suits.59 Suits over insult illustrate both types of procedure, particularly the investigatory.

The efficacy of a litigation depended on more than the execution of bureaucratic procedure. Judicial processes were able to bring angry individuals to closure on a dispute in part because of intangibles: They provided a ritual moment, a space conducive to changing individuals’ behavior, and community endorsement of the process. As Davies and Fouracre note regarding medieval Europe, the ritualized character of judicial proceedings “was the only way for legal institutions to make an impact on societies perpetually riven with antagonism and oppression. Ritual was the most effective way to channel off resentments in the direction of the idea of renewed peace.”60 Ritual was essential in largely oral societies such as Muscovy; even in this setting, where written records were scrupulously kept, the general orality of the society meant that ritual communication retained impact.61

Muscovite law codes protected the space of the judicial arena by explicitly forbidding disruptive behavior before judges. As the 1649 code said: “Both the plaintiff and the defendant, having appeared before the judges, are to sue and answer for themselves politely, and humbly, and without noise, and they should say no impolite words whatsoever before the judges and should not argue with each other.” The 1649 code went on to levy harsh fines for litigants insulting each other or striking or wounding anyone in the presence of the judge; such behavior was considered a dishonor to the judge.62 Legislation from the beginning of formalized Muscovite codes in 1497 also worked to elevate the dignity of the courtroom by inflicting punishments on corrupt judges and judicial officials and standardizing judicial fees.63

The ritual atmosphere of a judicial process in Muscovy was invoked from its very inception by the form of the petitions with which plaintiffs first addressed the court. Here the circumstances and specifics of an insult were spelled out and a request for resolution was made in florid, emotional, formulaic rhetoric: “Merciful sovereign, Tsar and Grand Prince Aleksei Mikhailovich, autocrat (samoderzhets) of all Great and Little and White Russia, favor us, your orphans. Grant, O sovereign, your sovereign trial and judgment against him Vasilii and against Peter for their robbery. Tsar Sovereign! Have mercy on us! Grant us your favor!”64 It was heightened by the formulae with which scribes drafted petitions for litigants. Petitioners called themselves “slaves,” “orphans” or “beseechers of God,” symbolizing their elite, taxpaying, or clerical status, respectively. They used diminutives for their names or for their homes (dvor becomes dvorishko, dom becomes domishko) or to describe their plight (“humble little dishonor”—beschestishko).65 They beseeched the tsar’s personal favor, often with heartrending details that approached tropes: “For our many services, and for the blood and deaths of our kinsmen, and for our many wounds, and for our mutilation and our time in captivity….”66 Adding to the ritual quality of a trial was the formal taking of testimony and the ritual of oath-taking, discussed in the next section. One litigation even speaks of sealing an amicable settlement with a kiss.67 The formality of the proceedings and the respect accorded officers of the court provided litigants a space in which to transcend their animosities, to speak the truth, and to defer gracefully to the weight of evidence, to the spirit of reconciliation, or to the judgment of the court.

In Muscovy, trials had an important social component. The community was present in the courtroom, not only in the form of judicial officials (many recruited locally), but sometimes in the form of representatives of the community. By fifteenth- and sixteenth-century law codes, judges—who were military servitors sent from Moscow—were required to render their verdicts in the presence of and with the participation of representatives of the community, called “men of the court” or “good men” (sudnye muzhi; liutshchie or dobrye liudi).68 Such leading citizens were given significant say in the administration of criminal justice. They were usually the more propertied residents or the longtime settlers of a rural community, and they could be communally elected officials. They paralleled the “good men” (boni homines, scabini) ubiquitous in medieval European adjudication, whom Susan Reynolds regards as representative of a reservoir of “legal procedures and norms” common to European lands from England to northern Italy before 1100.69 The responsibility of local “good men” in trials was not only to curb central officials’ excesses, but—equally importantly—to exert community pressure on all parties to conform to the court’s decisions. The “good men” also carried significant weight in assessing the character of fellow community members: Accused criminals considered by a community’s leading members as notorious (vedomye likhie liudi), carrying the connotation of recidivists, were punished far more harshly than those of whom community leaders approved.70

This principle of community involvement in the law was also embodied in the devolution of significant administrative and judicial authority to local “elders.” In the first half of the sixteenth century, local criminal affairs were given over to boards of local gentry (criminal or gubnye officers and their staffs), and by midcentury, fiscal administration was also given to “elders” (starosty) elected from the taxpayers.71 These institutions endured into the seventeenth century in the North and only gradually faded in the Center and frontiers, remaining most active in criminal affairs.72 Thus petitions from the North were typically addressed to a large collective judicial apparatus, such as “the church elder, the leading citizens, and all peasants” of the commune, cited in a petition of 1634 in Ustiug Velikii.73 Similarly, in 1640 in Vologda, monastic peasants were judged by a court that included two monastic elders, an elder of the peasant commune, and elected peasants. Even in the Center, where the governor’s central administration absorbed much community participation in the seventeenth century, elected officials could still play significant roles. In 1667, for example, the tsar ordered a local criminal official (gubnoi starosta) to execute a punishment because the local governor was a friend of the guilty party.74

Even as community representatives lost independent judicial influence, community interests were never absent from adjudication. The typical staffing of judicial offices with men from the community ensured that familiar faces would surround litigants at court. Many provincial governors (who were simultaneously judges) in the seventeenth century were local figures, although in principle, governors were not supposed to be appointed to their local communities. Valerie Kivelson has found that in practice, in seventeenth-century Vladimir-Suzdal’, one-fourth to one-third of the governors “appear to have had longterm, multi-generational ties to the towns they governed.”75 As men of local stature, they might be expected to exert more influence on litigants than a stranger would, and they might be more adept at forging settlements or suiting punishment to the crime when members of their own community were at issue. Kivelson argues that when gentrymen petitioned in the seventeenth century for locally elected judges and local courts, they were seeking “more intimate local justice”: “Judges would know the community and the character of its members and would be able to take into account the reputation, social standing and family status of litigants.”76 Lesser judicial figures—for example, the staffs of brigandage elders, court bailiffs and scribes—were also recruited from the local populace. Community inquests involved even more local people in the affair, giving them a stake in making the resolution stick. Muscovite adjudication took place in a community-aware environment. One is reminded of Susan Reynolds’s comment that medieval trials were more like informal assemblies than courts.77

The presence of “good men,” community “elders,” locals as judges and bailiffs, and local witnesses and sureties enhanced the flexibility and power of the judicial process. As Davies and Fouracre point out in regard to medieval Europe, the efficacy of adjudication “hung, not on any abstract institutional structure, but on the local community, its social attitudes and its private personal relationships.” They further argue that public approbation of the court system was a principal incentive for medieval people to litigate: “The key advantage of going to court was the width of support potentially available to a party there.” Litigants would “construct” the support not only of witnesses but of kin, neighbors, clients, and dependents, who would more readily step forward because of the catalytic quality of a trial. “By and large the support one received at court was available on the assumption that a lasting end to the dispute could be obtained thereby…. Courts were the most public, that is definitive, arena available to people…decisions and agreements made there were more binding than any fait accompli established outside them.”78 Such observations apply to Muscovy as well. Participation by members of the community as officers of the court, popular representatives, witnesses, sureties, or even spectators could advance litigants’ goals, as well as shape the process to suit the community’s perception of the offense and the offender. As we shall see, Muscovite litigations drew amply on community participation.

Strategies of Litigation

Once the plaintiff decided to sue, he and all the other participants in the trial made choices about the course of a trial based on political and economic calculations, on the expected results of different courses of action, and on social norms.79 As Laura Nader and Harry F. Todd, Jr., write, “Disputes are social processes embedded in social relations.”80 In premodern settings, the purpose of litigation was rarely to test a disputed behavior against an objective legal standard or to punish deviation, as it is—at least in theory—in modern litigation.81 Rather, as Philippa Maddern argues, the function of litigation “was less to punish criminals than to achieve certain stages in the legal process which would bring pressure to bear on defendants.”82 Litigants, in short, used the judicial process to serve their various objectives.

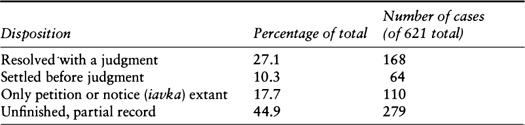

Disposition of Cases Studied

For many litigants, the process apparently stopped with the initial petition, judging by the high number of unresolved cases in the database. Of 621 adjudicated cases, only 168, or just over one-fourth, were resolved with a judgment and sentence (see the table).83 This finding is paralleled by studies of litigations in many settings. Philippa Maddern found criminal verdicts in fifteenth-century England to be “very rare,” amounting to approximately 11% of cases she surveyed in East Anglia; Elizabeth Cohen observed that many suits over insult initiated in Renaissance Rome “seem to have been dropped or settled in other ways,” as did Martin Ingram regarding defamation suits in sixteenth- and seventeenth-century Wiltshire.84 In many cases, of course, loss of documents explains a suit’s incompleteness. But the large incidence of unresolved cases suggests that document loss is insufficient explanation; I survey possible explanations here.

As with the principle of the notice (iavka) discussed in Chapter 2, the public declaration of an accusation often seems to have satisfied the plaintiff, perhaps because it had a deterrent effect on misbehavers or perhaps because it satisfied community expectations that one would defend one’s honor.85 Alternatively, some plaintiffs might have been deterred from pursuit by the cost and bother of litigation; as Ingram puts it in regard to early modern England, “rancour evaporated or the money ran out.”86 Landed servitors, who were expected to litigate in Moscow, had the greatest difficulty. Numerous petitions testify to their difficulties in meeting court dates when their military obligations took them to far frontiers of the realm. It is no wonder that in the seventeenth century, provincial gentry petitioned the government repeatedly for a local judicial system to avoid the hardships—corruption, red tape, and expense—of litigation in the capital.

Many litigations at some point in the process yielded to the pressure to settle, amicably or not. Motivations to settle were powerful, perhaps because they stemmed from so many sources. At the individual psychological level, Erving Goffman argues that people acting in society conduct themselves in a primarily “accommodative” manner so that all can maintain their socially constructed identity, or “face.” Individuals will often ignore or forgive an insult rather than exacerbate a tense situation.87 On the social level, such accommodation maintains or restores stability. Community interests favored face-saving settlement, because unresolved quarrels in small communities could escalate into a headache for the whole village. Settlement generally accomplished that goal better than bringing a case to verdict. As Davies and Fouracre point out regarding a range of early medieval European cases, “In all the societies we have looked at here, no matter how violent, it was recognized that it was better for disputes to end.” Thus, “The purpose of much dispute settlement was not in any strict sense justice, but the restoration of peace.”88 In many premodern European societies, litigation was frowned on as an antisocial step until reconciliation had been attempted, and settlements were often regarded as more just and more binding than pursuing the letter of the law, because both parties emerged with dignity and satisfaction.89 In Robert Shoemaker’s study of misdemeanor prosecution in seventeenth- and eighteenth-century England, for example, a significant percentage of litigants who were personally acquainted settled informally: In the cases of two judges whose notebooks survive, 82% of litigants settled informally with one, and 66% with the other.90

In Muscovite suits over insult, sixty-four cases (10%) were resolved by written reconciliation (the documents were termed mirovye or “peace-making” acts). The number may seem small, but it is significant, inasmuch as it amounts to about one-third of the number of suits that were resolved by court verdict (168, or 27%). The circumstances and terms of settlements varied. Some litigants accepted the intercession of a mediator, whose role was so valued that if litigants refused to accept his decision, they were required to pay his dishonor fine and to forfeit a surety bond they had put up as earnest money.91 But by and large, litigants reconciled on their own, before or during a trial. For example, two gentrymen settled in 1639 the day after one had insulted the other “with a mother oath before all the town,” presumably before a trial had started.92 Two townsmen in Tikhvin settled in 1684 two days after a quarrel, with the defendant paying fees and agreeing not to sue again on this issue on penalty of ten rubles.93 On July 12, 1686, a widow sued two men for assault, theft, and rape, and on July 16, at the trial, one witness only partially supported her version of the events. That day the three settled during the trial, with the defendants paying fees calculated according to the woman’s dishonor fine, perhaps giving her thus a symbolic as well as material victory.94

Community pressure could no doubt come to bear in this process, inasmuch as the questioning of many witnesses made the litigation a public experience. In a 1640 case, for example, twenty witnesses testified that they had not heard the insulting words alleged in the suit of one Vladimir gentryman with another, other than that each had called the other a shirker from service (nesluga). The judges ruled that the reciprocal insults canceled each other out; both litigants immediately paid the court fees and did not protest the resolution. In an analogous case of the same year, a plaintiff (a foreigner in a new model regiment) lost his suit when nineteen witnesses could not confirm his allegations that another foreigner in his regiment had insulted him and his wife.95 A zhilets and a post driver in Tula settled in 1640 after an inquest of the community split: forty-one supported the plaintiff, and thirty-one denied all knowledge of the alleged insult and quarrel. In another case of 1640, more than forty community members were involved as witnesses or character witnesses; although the plaintiff won the case, the two men settled after the verdict. Perhaps the plaintiff agreed to forego the fine in the interest of restoring local amity, possibly pushed by community sentiment in the presence of so many neighbors.96

Other juridical processes also promoted the cause of reconciliation. Routinely, defendants and even plaintiffs were put on recognizance (poruka), a surety bond that promised that the principal would appear at the trial or else forfeit a sum put up by his guarantors. Not only did such bonds provide a “cooling off” period in which settlement or abandonment of a suit could occur, they also brought to bear the additional pressure of the guarantors, who not only stood to lose their bond but also were denied the legal right to sue the sponsored man for dishonor in case he defaulted.97 Robert Shoemaker argues that recognizances “often successfully resolved a dispute without further legal action; not much more than a fifth of the defendants bound over were subsequently indicted” in his large sample of misdemeanor suits.98 Many Muscovite cases were settled after one or both of the litigants were put on recognizance. In 1625, for example, a musketeer of Briansk sued a local cleric for insulting his daughter and son-in-law. The litigants were ordered placed “on sturdy recognizance” (krepkaia poruka) and brought to Moscow. In the face of that expensive proposition, they promptly settled the case. Similarly, on July 24, 1672, in Voronezh, an infantryman sued his brother over a quarrel that had taken place the previous day; they each gathered sureties and named witnesses. On August 18, they settled out of court before witness testimony was taken; the brother agreed to pay court fees.99

Suits that were not settled early on proceeded to the collection of evidence. Plaintiffs presented their side of the story to the judge, naming witnesses or presenting relevant evidence, such as marks of injury or documents. The judge questioned the defendant, who sometimes also then sued the plaintiff for false accusation or for the “dishonor” of the present suit. Defendants had the right to exclude witnesses based on enmity or kinship; if both disputants could find a common witness (obshchaia pravda) or witnesses whose testimony they agreed to, that testimony would decide the case. Sometimes litigants requested, or judges ordered, a general inquest (poval’nyi obysk) of the community to gather evidence. According to long-standing tradition, such inquests sought character references as well as firsthand eyewitness evidence. Law codes throughout the Muscovite period fought this trend, advising that witnesses “should not testify if they have not witnessed, and having witnessed should testify truthfully.”100 But character references and hearsay continued to play a large role in inquest testimony, leading to the abolition of general inquests in 1688, a reflection of increasing judicial preference for more objective evidence (documents and individual eyewitness).101

Many cases show the importance of witness testimony in advancing or resolving a dispute. In 1640, for example, a group of nineteen men, identified as “common witnesses,” failed to support the plaintiff’s claim that a fellow foreigner in Muscovite service had insulted him and his wife. He lost the case. In 1641, a gentryman sued another for insulting him in the governor’s office; a common witness testified in favor of the plaintiff, and he won the suit. Similarly, in 1676, a peasant sued a priest in the Sukhona River area in the North for insult by a mother-oath; two common witnesses—a priest and a peasant—supported the plaintiff. The priest lost the suit. In 1680, a musketeer in Rylsk lost a suit over assault on his daughters by the daughter of an artilleryman because a “common witness” of seven men failed to support him.102

In the absence of conclusive witness or written testimony, litigants agreed to let the judgment of God resolve their dispute through some sort of ordeal, again highlighting the ritual character of court proceedings. Although judicial duels were still countenanced into the seventeenth century,103 in the materials covered by the database only the ordeal of oath-taking by kissing the cross is attested. The procedure was executed by a priest accompanied by representatives of the local officialdom and populace as witnesses. Both litigants attended. The one who had agreed to an oath was called to the cross three times, and on the third he was asked to swear. If he failed to appear or refused to take the oath, his opponent won the suit. If both the litigants agreed to take an oath, they threw lots to determine who would swear first.104

The efficacy of oath-taking as a means of resolving disputes was, judging by these cases, apparently great. Not one of the many called to take an oath actually went through the full ritual and kissed the cross; they backed out along the way. In many cases, both litigants stated their willingness to take an oath, but did not act on it; they resolved the case on the basis of witness evidence or amicable settlement instead.105 When they did move toward the actual oath-taking ritual, litigants either abandoned the litigation along the way or settled. In most cases, litigants settled once an oath had been ordered, before the ritual had begun, or at the first of the three summons.106 Some cases simply stopped once an oath was mentioned.107 Some litigants facing an oath sued for delay and then never showed up to one or another of the three summons.108 Some cases offer interesting details. In 1641, for example, two gentrymen of Elets (south of Moscow) litigated over dishonor incurred in a property dispute. The plaintiff reported that he stood to the cross kissing three times, and at the third time, the defendant intervened and agreed to settle the case and pay the court fees. The defendant then proceeded to drag his feet on paying the fees, until it was reopened three years later and the fees were collected from the defendant’s sureties. In 1642, a defendant halted the ritual at the second summons to the cross, offering to come to agreement with the plaintiff, because he “did not want to commit sin” (presumably by falsely swearing). More magnanimously, in 1690, a defendant stopped the plaintiff from kissing the cross at the last summons and agreed to pay all court fees.109

Sanctions and Mercy

The ways in which litigants pursued cases display their essential confidence in the judicial system at the same time that they demonstrate individuals’ subjective manipulation of the process. They pursued suits or settled as the spirit moved; they yielded to public pressure; they cowed in the face of eternal damnation with cross in hand. Until the case went to the judge, the judicial process allowed flexibility and gave wide range to achieve maximum satisfaction for all sides. When judges took the stage to decide verdicts, their ability to enforce compliance with their judgments depended in part on litigants’ faith in the judge’s impartiality and in the system as a whole. Judges’ efficacy was also enhanced by the latitude with which they could respond to the specific circumstances of a suit.110

When judges resolved a suit over insult, what was particularly at issue was not the truth of an allegation, but whether in fact the insulting words had been uttered. There were some exceptions. Law codes, for example, specified that an allegation of illegitimacy was dishonoring if proven false, and indeed in one case a man’s parentage was investigated to establish his legitimacy.111 Case law also suggested that it was not dishonoring to label a man a “traitor” or “deserter” (beglets) if the accused had indeed fled the scene of battle; the insult was otherwise very serious.112 Accordingly, individuals took great pains to refute allegations of dereliction of military service, pointing out their own and their families’ long years of faithful service.113 False accusation of criminal activity was in theory treated harshly: A decree of 1582 mandated execution for false accusation of thievery (a frequent insult in the suits in the database), whereas the 1589 law code declared false accusation dishonoring to the victim.114 Defendants sometimes argued therefore that they called a plaintiff a “thief” justly because he had been convicted of theft.115 In practice, however, most insults were too generic to be disproved one way or the other (“son of a bitch,” for example), and most slurs hurled in dishonor disputes tended not to be taken literally. Judges did not investigate criminal records when a man was called a thief (vor); ascertaining that the insult was uttered, they convicted the defendant.116

Muscovy’s contemporaries followed the same principle. English law declared “It matters not whether the libel be true, or whether the party against whom it is made be of good or bad fame.” French law paralleled this attitude.117 The issue at stake was more the socially destabilizing effects of hot words and reputation-ruining slanders than literal truth. Muscovite law codes did not expressly state the principle that was at the root of European canon and civil law against defaming language, but the practice of such litigation shows similar concern: the principle that slanderous language was a breach of the common peace, an act that might engender further violence, tension, and fissures in the community.118 Clearly the court’s interest in establishing the fact of an utterance rather than its validity expresses this same view: Individuals could not be allowed to inflame passions, defame neighbors, and rile up kindred and community. Judicial processes provided a forum for restoring an individual’s social position when threatened, for forcing apologies and reconciliation when possible, or for administering penalties when insulters refused to back down.

In imposing sentences, judges tended to follow the guidelines established by the 1550, 1589, and 1649 law codes. In the few cases before 1649 for which we know the resolution, the 1550 law code’s guidelines for monetary compensation seem to have been followed. We find a boyar receiving a large cash payment in 1571 for dishonor and a diplomat paying for insulting a gentryman’s wife in 1594.119 In some cases, however, judges were harsher than the law prescribed. In 1626, for example, a landless peasant was beaten for insulting a priest, when corporal punishment was not at all recommended in the 1550 law code. Also excessively harsh was a 1635 ruling in which a gentryman was sent to a ritual of humiliation for insulting his sister-in-law. Perhaps here the severity stemmed from the familial relationship involved.120 Similarly, in 1642, a stol’nik was corporally punished for insult to another stol’nik’s widow, when a cash fine should have been the sentence.121

After the 1649 law code was issued, the range of sentences for dishonor expanded to include incarceration and corporal punishment as well as cash fines. As detailed in Chapter 1, the type and severity of punishment varied according to the social status of the insulter and insulted parties. As a rule, after 1649, judges followed these guidelines, aided by the wide distribution of printed copies of the Conciliar Law Code (many of the suits I cite include verbatim excerpts from the code). We see in 1675 a boyar paying a stol’nik his cash salary for insulting him, a gentryman paying a cash fine to a peer in 1683, an infantryman paying cash to a peer in 1684, and a peasant paying a cash fine to another peasant in 1697.122 When judges strayed from the guidelines, they did not stray far, sometimes slightly mitigating punishment. In 1666, for example, a land elder (zemskii starosta) was sentenced to beating by bastinadoes and a week in prison for insulting a governor, when the law required beating by knout and two weeks in prison.123 In 1667, when a son was beaten for insult to his mother, the sentence was mitigated by his being beaten with bastinadoes, not the mandated and harsher knout.124

Judges could intensify sentences because of the severity of the insult. In 1650, an undersecretary was sentenced to exile in Siberia for insulting a man of the Moscow ranks by submitting false evidence in a trial against him. For dishonor in this case, the punishment would normally be a cash fine. Harsher punishments also came when the insult was accompanied by the failure to obey orders in a military or administrative setting, as in 1660 when a governor was ordered to pay a cash fine and spend three days in prison for not handing over troops to the local musketeer regiment as ordered. Normally, dishonor to musketeers by a governor would merit a cash fine alone. In a case from July 1649, the eminence of the victim, the tsar’s close advisor Bogdan Khitrovo, probably accounts for the intensified punishment: A servitor was ordered beaten with a knout for insulting the okol’nichii Khitrovo, when by the 1649 law code, the penalty should have been a cash fine.125

Judges enhanced their ability to enforce judgments by the strategy of publicity. In announcing or carrying out sentences, they mandated the presence of witnesses. This practice was particularly valuable in dishonor litigations when the aggrieved party wanted to ensure that the community be made aware of his or her vindication. Corporal punishment was generally to be carried out in public view, for deterrent effect as well as to enlist community approbation. In 1640, for example, a high-ranking Muscovite servitor was found guilty of insulting a judge and was ordered imprisoned; the order was announced “at the Military Service Chancery before many people.” In 1677, the military governor of Briansk was ordered imprisoned for a day and an undersecretary was ordered beaten “mercilessly” with bastinadoes instead of the knout for having submitted a document with an improper form of the diminutive for the governor’s name. The presiding officer was instructed to read the judgment against the two men out loud “in the local administrative office (s’ezzhaia izba) before many people.” And in 1687, a commander in a new model cavalry unit was ordered “beaten with a knout before the whole regiment” for dishonor and disobedience to his colonel and for drunkenness.126 For the highest social level, public rituals of humiliation were prescribed (see Chapter 4), whereas sometimes a particular form of beating with the knout was prescribed, which involved beating the victim while he was led through town (the so-called “marketplace punish-ment”).127 The public nature of some sanctions attests to the utility of social pressure in adjudication: Public knowledge of unacceptable behavior shaped community opinion about an individual, enlisting, as it were, the involved community to supervise the subsequent behavior of the punished individual.

Another aspect of the system of punishments worked in a different way to pursue stability: the provision of mercy in sentencing. Again, this is not unusual in the premodern European context. In England, for example, judges often found reason to mitigate sentences, doing so, for example, in about two-thirds of the criminal convictions that Cynthia Herrup analyzed, and exerting considerable flexibility in fining for convictions in Robert Shoemaker’s study of Middlesex county misdemeanors.128 In Muscovy, mercy was proffered in the name of the tsar and construed as his personal “favor”; it was reserved for members of the privileged elite. In 1657/58, two men of a boyar clan were ordered beaten and fined for dishonoring another boyar clan in the Kremlin; the tsar remitted the beating (but maintained the fine of 1,590 rubles). In February 1683, a zhilets was ordered beaten for dishonoring the tsar’s palace and fined for dishonoring another zhilets; the tsar lessened the beating to a prison term and then released the defendant from prison when he petitioned for further mercy on the basis of his old age and ill health. Similarly, in the 1687 rape case discussed at length in Chapter 2, a military servitor was sentenced to exile to the Solovetskii Monastery in addition to paying a hefty fine in lieu of the shamed woman’s dowry. The tsars rescinded the exile, but not the fine. And in a remarkable case, in the summer of 1684, Tsars Ioann and Petr Alekseevichi and regent Sofiia Alekseevna ordered a gentryman executed for insolence because he had approached them with a request to reconsider a suit that they had already personally resolved. Then they bestowed mercy, levying a fine instead. But on September 16, he again appealed, “forgetting the fear of God and despising their copious and surpassing mercy,” prompting the tsars again to order him executed to deter others “in the future.” On October 3, 1684, they again bestowed mercy “in honor of the tsar’s many-yeared health,” announcing the reprieve to the unfortunate man at the last minute “in Red Square at the execution place.”129 Thus mitigation of a verdict, in addition to minimizing hardships, worked to uphold the privilege and dignity of the elite ranks and the image of a benevolent as well as just tsar.

Mercy could also emanate from the plaintiffs themselves. An element of mercy is to be found, for example, in plaintiffs being willing to forego compensation even after they had won a suit. In 1641, for example, a zhilets won a suit against a post driver in Tula for insult to him and assault on his man. Then they settled the suit, with the defendant paying the court fees. On May 20, 1685, a townsman of Kolomna won a suit against a peer for insult to him, his wife, and his two sons; the defendant proved unable to pay the dishonor fine of twenty-eight rubles plus court fees, and on July 18 they settled, with the plaintiff forgiving part of the debt and receiving a deed for land for the rest. In a 1687 case, two highly ranked Moscow servitors sued for insult: The more senior of the two, a dumnyi dvorianin named Izvolskii, alleged that the defendant, a state secretary (d’iak) by the name of Poplavskii, had insulted him and refused to work under him in a chancery. The defendant countersued, saying that Izvolskii had said to him, “Your worth, you farm laborer, is a penny. I’ll throw you out of the chancery tomorrow,” and had additionally insulted him at his home. Even though Izvolskii won the suit, for which his 365-ruble annual salary was levied on the state secretary as a fine, he agreed to settle the suit because “He [Poplavskii] has apologized to me.”130

Even more magnanimously, winning plaintiffs occasionally petitioned for punishment to be revoked or mitigated. In 1683, for example, a gentryman, B. I. Kalachov, was ordered beaten with a knout “on the stand” (na kozle)131 for insult to Boyar Prince Mikhail Andreevich Golitsyn. On November 8, this order was read to Kalachov in front of the Military Service Chancery, but, as his clothing was being removed, Prince Golitsyn’s man intervened, conveying the boyar’s petition for mercy, asking that Kalachov not be beaten for the sake of Golitsyn’s honor. And so he was reprieved. The Golitsyns were a compassionate lot, it would seem. In March 1692, Prince Boris Alekseevich Golitsyn won a suit for insult to him and his father in the tsar’s quarters against two men of the Dolgorukii princely clan. The two were ordered imprisoned for insulting the dignity of the tsar’s residence and were fined more than 1,500 rubles for the younger Golitsyn and an equally large amount for the father. The tsar in his mercy pardoned them the prison sentence, but not the fine. The two Dolgorukii princes protested the imprisonment and the huge fine, saying “We had a simple and common disagreement, the type that often occurs among servitors who have an enmity,” citing the Conciliar Law Code of 1649 to suggest that the punishment was excessive and declaring that the Golitsyny were out to destroy them and their clan. In July 1692 and March 1693, they petitioned the court, claiming to be unable to pay such a sum. Three years later, in May 1695, they won a reprieve from the Golitsyn family patriarch, who sent word from his deathbed that he in the name of the family forgave them the dishonor and the fine.132

Why would litigants make such benevolent gestures? Perhaps it had to do with individuals’ sense of their own honor. Recall Julian Pitt-Rivers’s remarks on honor discussed in the Introduction. He argues that in many societies, the concept of honor has “two registers”—one the adamant defense of one’s honor and the other the magnanimous forgiveness of a rival once one’s honor has been defended.133 This spirit of honor, plus the fact that most Muscovites embraced Christian values of charity to one’s neighbors, contributed to the spirit of magnanimity. Particularly when it came to insult, as I have discussed in this and earlier chapters, the restoration of stable social relations by rehabilitating reputation was important to communities and individuals.

Emphasizing only the stabilizing effects of litigation creates a misleading impression. First, it would be premature to do so. One would need to examine a larger selection of different kinds of disputes in a geographically limited setting and test how different groups—men, women, the poor, the privileged—experienced the law. Historians have argued that significant social groups were excluded or disadvantaged in premodern adjudication; in particular, women and the poor suffered harsher penalties or more limited access to the courts than did propertied litigants and thus did not so readily experience the law as a stabilizing or mediating social instrument.134 The same might have been true in Muscovy. Second, as I have suggested, Muscovites complained of judicial corruption and abuse. Finally, litigants could use courts to antagonize their rivals.135 In suit after suit, we find litigants complaining that a party in a suit fails to cooperate, will not pursue an initiated case,136 has left town in the midst of a suit,137 refuses to pay a fine or fulfill the terms of a settlement,138 harasses them with litigation, and the like. In the seventeenth-century petitions against local factions cited above, gentrymen described the depredations of these sil’nye liudi: “And we, your slaves, suffer great injury and losses from them in their great slanderous suits; they serve on us, your slaves, and on our slaves and peasants, summonses to court, counting on the fact that they do not pay judicial fees and they cheat. us, your slaves, and our slaves and peasants deliberately.” They go on to explain how wealthy landholders manipulated the court system to prevent lesser gentry from recovering runaway serfs from them. A dishonor suit from 1690 echoes these sentiments. Two Novgorodian gentry-men expressed their helplessness in suing a neighbor for his twenty-two-year pattern of false accusations and harassment of them: “And we cannot sue him for dishonor; he is too wealthy.”139

Insult and dishonor suits could be a spiteful strategy of negotiating local tensions. A long-simmering dispute between a gentryman of Zemliansk by the name of Plotnikov and a local undersecretary named Okulov, for example, apparently boiled over in April 1682 when the two fought and exchanged insults at Plotnikov’s home. Okulov said Plotnikov and his family had long been harassing people in the village, and Plotnikov called Okulov a thief and murderer and charged him with assaulting and insulting his sister and her property. The transcript dryly records that “The trial could not be concluded because all the parties were quarreling among themselves.” When the case was referred to Moscow, Okulov was ordered to cease his work in Zemliansk until the charges were investigated. The case dragged on at least three more years, with new charges and countercharges. As far as extant documentation shows, it was never settled.140 The tsar’s courts imposed penalties, collected bond from recalcitrant individuals’ sureties, or confiscated property, but nonetheless, many such litigants managed to obstruct justice. In several cases, losing defendants, for example, dragged cases on without paying the fines for a year and a half—or three, eight, fifteen, seventeen, even eighteen years.141 They requested overly harsh sentences or continued insults and threats after losing a case.142 All in all, litigation could be an avenue for exacerbating personal and local stresses.

Muscovy’s was not a perfectly equitable judicial system, but social institutions can always be manipulated in these ways. The relevant question is the degree of satisfaction individuals found in these processes. I have argued here that as a rule, individuals were more interested in winning public acknowledgment of their honor and a speedy resolution to a dispute than they were in harassing rivals. For most litigants, the judicial process seems to have worked well enough. Plaintiffs felt they would receive satisfaction, and defendants participated in the system because those who flouted it risked punishment. For all concerned, failing to appeal to justice posed even greater losses. Without recourse to the court, communities could be rife with feuds, vendettas, and unresolved tensions that affected daily life for many. Going to court offered sufficient flexibility that could meet the needs of individuals, communities, and the state.

Trials concerning insult to honor are particularly illustrative of the legal process at work for two reasons. First, insult to honor created moments when community relations were crystallized. Insult was often the culminating point in a simmering dispute: To really get at one’s rival, one publicly shamed him or her. Second, honor litigations necessarily mobilized communities. Because honor is as public as it is private—an insult without witnesses has no ramifications on the accused’s social standing—resolution of the affront needed a public forum. The more witnesses who could be called forth to reject the slander and the more public the process, the more secure the individual and the community emerged in the protection of their common norms. If the state had not lent courts, laws, and legal procedure to regulate this process, communities would have invented their own rituals, forums, or acts of violence to accomplish the task.143 The state was involved, however, fulfilling the traditional duty of medieval rulers as judges. Individuals took advantage of a system that was as a rule “legal”: predictable, limited, and publicly defined. In the process, the state gained some symbolic and some real benefits as well.

1Phrase from Wendy Davies and Paul Fouracre, eds., The Settlement of Disputes in Early Medieval Europe (Cambridge, England, 1986), p. 234.

2H. W. Dewey, “Old Muscovite Concepts of Injured Honor (Beschestie),” Slavic Review 27 (1968):598.

3The more specific breakdowns are as follows: social equals suing each other within the Moscow-based elite (93); gentrymen (105); taxed groups, including contract servitors (158); clergy (21); and foreigners (5). Social superiors suing inferiors: Moscow-based servitors suing gentry (24), taxed people (39); gentry suing taxed people (34); and clergy suing taxed people (18). Social inferiors suing superiors: gentry suing Moscow-based servitors (9); taxed suing privileged ranks (48); and monks and parish clergy suing the military elite (12).

41579: RIB 14 (1894), no. 62, cols. 117–18. 1590: RIB 14, no. 69, cols. 130–31.

5RGADA, f. 210, Prikaznyi stol, stb. 1061, ll. 50–51. This descendant of the Siberian Tatar ruling family, which was under Moscow’s suzerainty, served in Moscow.

6G. A. Anpilogov, ed., Novye dokumenty o Rossiikontsa XVI–nachala XVII v. (Moscow, 1967), pp. 375–77.

7Moskovskaia delovaia i bytovaia pis’mennost’ XVII veka (Moscow, 1968), pt. 2, no. 76, p. 83. Other incidents with ob’ezzhie: RGADA, f. 210, Prikaznyi stol, stb. 1203, ll. 10–14, 20–26, 59–60, 163–66 (all 1690).

81520s: S. Bogoiavlenskii, ed., “Bran’ kniazia Vasiliia Mikulinskogo…,” Chteniia, 1910, bk. 3, Miscellany, pp. 18–20. 1687: RGADA, f. 210, Prikaznyi stol, stb. 1063, ll. 82–104. Other complaints against corrupt officials: AMG 1, no. 241, pp. 259–61 (1629); no. 277, pp. 309–10 (1630).

91626: RIB 14, no. 301, cols. 673–74. 1644: RGADA, f. 210, Belgorod stol, stb. 174, ll. 312–15.

101627: RIB 25 (1908), no. 44, cols. 46–47. 1633: RIB 2 (1875), no. 152 (2), cols. 522–25.