chapter 5

Strategies of Integration in an Autocracy

Muscovite rulers were faced with the same problems of governance that confronted medieval and early modern rulers in Western Europe. They had limited resources in manpower and finances and limited means of communication (even after printing was accepted, literacy was required to make it a tool of governance). Population was widely dispersed and heterogenous in dialect, confession, social status, and privileges. In such circumstances, rulers were hard pressed to integrate their realms, and in fact strove for nowhere near the degree of social and political cohesion that states seek today. To achieve stability through societal acceptance of their rule, premodern leaders adopted strategies from coercive to co-optative—fulfilling the traditional mandate of providing justice was one. Concepts and institutions of honor can be seen, from the state’s point of view, as a strategy of governance, one that provided a discourse and a cultural praxis uniting the tsar’s territory around a common set of social values. Honor contributed to Muscovy’s social and political integration in tandem with a broad array of other strategies. Those strategies constituted the political practice of the realm. This chapter, then, explores the issue of social cohesion in premodern conditions and in so doing confronts the meaning of autocracy in action for Muscovites.

Theoretical Discourses about Cohesion

We might define social cohesion or integration as societal acceptance of the governing authorities that is sufficient to create stability and to allow those governing bodies to pursue their goals. F. G. Bailey remarked how even the seemingly strongest of regimes fall apart when societal consensus evaporates: “To a surprisingly large extent people can be ruled only in so far as they are willing to accept orders…. Consent, of course, means more than merely willingness to accept a particular command. It means accepting the pattern of statuses which divide people into high and low.”1 Social cohesion involves both command and acceptance, ideology and practice. Perceptions of how cohesion is achieved and actual practice dialectically influence each other: A society’s formal discourse about how it is unified may create conditions for greater or lesser cooperation with strategies of building cohesion, and vice versa. In this section, I look theoretically at how cohesion might be achieved and contrast to those ideas the ways in which Russians have described cohesion in their state over time.

How to create social cohesion is a problem that has troubled rulers and philosophers since the time of Aristotle and Plato. Great social theorists have carved out two approaches to the problem, points of view implicit in the pairings of those two ancient philosophers and of others who followed—Hobbes and Rousseau, Hegel and Kant, Marx and Weber.2 One approach focuses on coercion, based on an assumption of natural competition and conflict in the human condition. Variations on this theme are myriad, but a most influential modern version of this Hobbesian view has been the Marxian one, wherein each age is permeated by a dialectical tension between the dominant class’s efforts to maintain its control and the struggle of subordinate classes to overthrow it.3 The other common paradigm emphasizes consensus, based on an assumption that integrated harmony can be achieved in human societies. Again, many variations have been articulated. Often this image of society is linked to an evolutionary perspective, as in Ferdinand Tonnies’s contrast between “traditional” societies (Gemeinschaft)—founded on personal interaction, affinitive relationships, and ascribed status—and modern societies (Gesellschaft)—characterized by individualism, territorial association, and contractual relations.4 A most influential exponent of this vision was Emile Durkheim, who saw at the heart of social stability normative consensus—that is, the internalization and acting out by individuals of moral values conducive to social cooperation and the maintenance of the social system.5

Much twentieth-century social theory has tried to reconcile these approaches. Max Weber balanced the coercive force of the state with systems of legitimation and status as building blocks of social cohesion.6 The revisionist Marxist Antonio Gramsci argued that modern societies are stabilized by the “cultural hegemony” of the ideology of the dominant class.7 Modern social anthropology stresses both the restorative power of ritual and ideology and the possibility of dynamic interaction between rulers and ruled in such ceremonial moments or discourses: Max Gluckman finds “the peace in the feud”; Victor Turner sees rites of passage as transformative and reconciling; and Clifford Geertz argues that ideology as expressed in cultural praxis creates moments of interactive communication.8 Current theory in sociology and anthropology, as well as postmodernist critiques,9 balance the coercion-consensus tension by reference to human agency. They thus look to “praxis”—that is, the willful (in Anthony Giddens’s term, “knowledgeable”) interaction of individuals with the institutions and ideas that shape their experience. Sherry Ortner summarizes: “Society is a system…the system is powerfully constraining, and yet…the system can be made and unmade through human action and interaction.”10

Anthony Giddens and Michael Mann, among others, are of particular interest here because they focus on premodern societies.11 Following Foucault and others, they see power as diffused throughout society; accordingly, they hold that social integration cannot be fully controlled by the center. The claims of premodern governments are broad but their ability to exercise such claims shallow. Thus, when Mann and Giddens turn to strategies of central control, they identify a variety of means that are coercive and consensus-building. Giddens speaks of military power, or the threat thereof; bureaucratic control over those social resources deemed important to the dominant classes; and inculcation of generally personalized theories of legitimation, for the elites in particular. Underdevelopment of transport and communication as well as of literacy, education, and media means that neither economic control nor normative consensus alone can create and sustain societal integration.

Keenly aware of the limited resources in premodern conditions, these sociologists also argue that states focus cohesion-building strategies mainly on the elite because its support is most crucial to administrative control and because it is the most accessible by the limited means of communication in premodern conditions. What they describe, in sum, is not top-down social control but something more interactive. The family and household turn the social values of religious and secular ethics into personal goals; locally based office holders amass power by enforcing laws and moral expectations; factions within communities assemble power bases using central bureaucratic offices; and individuals and institutions that enforce social values or policy in turn benefit from rewards in the form of land, status, access, and so on. The permeation of social structures and cultural practices with a discourse that both encourages conformity and allows the possibility of negotiation and gratification creates loosely bound community and dynamic stability.12 Thus theoretical considerations of social cohesion now see it as a process of interaction between, on the one hand, received discourses and limits imposed by institutions and culture and, on the other hand, individuals appropriating and manipulating those institutions. My discussion of how individuals and communities used honor for local concerns takes this approach, stressing individuals’ “knowledgeable” manipulation of dominant discourses.

Russians writing on cohesion in their society have run the same theoretical gamut from coercion to consensus to an appreciation of the interdependence of the two. It is important to recall, however, that most of what has been written on this topic is didactic, whether emanating from the pen of a sixteenth-century chronicler bent on impressing Orthodox hierarchs, or of a nineteenth-century “Westernizer” convinced of the “enlightenment” of Peter I’s reforms of “backward, stagnant” Muscovy. But it is useful to survey this literature as evidence of trends in ideology and as a theoretical ideal to juxtapose against practice, which I turn to in the second half of this chapter.

No explicit theoretical discourse about society was present in Muscovite times, but one can glean different visions of societal unity from numerous texts. The coercion and the consensus models coexisted in contemporary Muscovite portrayals of Muscovite society and politics, but it is fair to say that the image of premodern Russia as bound together by coercive central control has enjoyed a dominance in most modern interpretation. The reasons can be found in Muscovite texts. The coercion model made a late but dramatic impact on Muscovite texts starting in the late fifteenth and sixteenth century, when the theme of the Muscovite ruler as “autocrat” emerged. It was a trend propelled by a conjunction of events: the fall of Constantinople in 1453, the demise of the Golden Horde, Moscow’s phenomenal territorial expansion. Starting in the early sixteenth century, learned writers brought the stern dictum of the sixth-century Byzantine scholar, Agapetus, to their aid:

Though an emperor in body be like all other, yet in power of his office he is like God, Master of all men. For in earth, he has no peer.13

In the compilative projects he directed at midsixteenth century, Metropolitan Makarii constructed an image of Muscovy as heir to Byzantium and its ruler as Godlike in his power.14 In his Great Menology (Velikie minei chetii), compiled in 1552, Makarii included historical and hagiographic texts that portrayed Muscovy as “the center of God’s world” and assigned its ruler responsibility for defending the realm and the faith against all heathens—domestic heretics, Catholics, and Muslims.15 The Book of Degrees (Stepennaia kniga), compiled in the early 1560s under Makarii’s direction, included a eulogy to Vasilii III depicting his “autocratic” rule thusly:

His imperial heart and mind are always on guard and deliberating wisely, guarding all men from danger with just laws and sternly repelling the streams of lawlessness so that the ship of his great realm would not sink in waves of injustice…. For truly you are called tsar…who are crowned with the crown of chastity and draped in the purple robe of justice.16

Although the most immediate audience for these views was other churchmen and any literate members of the secular elite (of whom few were literate before the seventeenth century), this representation of power and omnipotence was portrayed in court rituals from the late fifteenth century. Their import was not lost on outsiders such as foreign diplomats, many of whom were already predisposed by classical training to see Muscovy in categorical terms. Sigismund von Herberstein, an early sixteenth-century Habsburg envoy, said about the Muscovite grand prince: “In the sway which he holds over his people, he surpasses all the monarchs of the whole world.” Several decades later, the Englishman Giles Fletcher likened Muscovite government to Turkish despotism: “The manner of their government is much after the Turkish fashion…plain tyrannical, as applying all to the behoof of the prince.” Aristotle’s concept of tyranny was invoked by the German traveler Adam Olearius in the midseventeenth century: “The Tsar…alone rules the whole country…he treats [his people] as the master of the house does his servants.”17 Their constructions of early modem Russia as “a dominating and despotic monarchy” became a powerful trope in the hands of seventeenth- and eighteenth-century European political theorists, as Marshall Poe has persuasively demonstrated.18 From their works, this idea migrated back to Russia.

Peter I’s adoption of a European rhetoric of absolutism at the turn of the eighteenth century and the vigorous cult of Peter that ensued guaranteed that this theme of omnipotent autocracy and slavish society endured through the eighteenth century.19 Not surprisingly, reinforced by Western images of Russia as exotic,20 this patrimonial vision dominated the debates about Russia in nineteenth-century social thought. The statist school, for example, gave primacy to the state and dismissed society as inert (S. M. Solov’ev, Boris Chicherin). Similarly, with the spread of Marxist historiography in Russia from the late nineteenth century, the coercion paradigm became the canon. However much modified by Stalinism and Russian nationalism, Soviet historical theory maintained that societies are unified by a specific form of political control arising from the dominant mode of production in a given era. Soviet Marxist scholarship saw pre-Petrine Russia, as well as much of Imperial Russia, as ordered and stabilized by the economic and political institutions of the state acting in the interests of the feudal class.21 In response, in this century a variety of anti-Marxist versions of the same model were developed that posited the primacy of politi-cal—rather than social and economic—forces in coercion. Such a trend, not coincidentally paralleling the rise of the totalitarian interpretation of the Soviet state, depicts early Russia variously as an “Oriental despotism” or a “patrimonial” or “hypertrophic” state, or otherwise emphasizes instruments of political control and coercion.22 These ideas are now enjoying vogue in post-Soviet Russia, where historians have been embracing Herbert Spencer, Arnold Toynbee, Richard Pipes, the Eurasianists, and the “totalitarian” model.23

But the primacy of this interpretation has by and large been driven by outside factors, among them clergy anxious to elevate Muscovy in the Orthodox world, intelligents swayed by the cult of Peter and the West, and Cold War tensions. It does not correspond well to countervailing ideas in writings of Muscovite times, nor to Muscovite practice. Muscovite texts and their Kievan predecessors overwhelmingly argue for a “consensus” vision of autocracy. From Kievan times to the seventeenth century, chronicles, other historical writings, and some documentary texts consistently depict the body politic as a harmonious, Christian community united under a tsar who was legitimized by God and limited by “law” and tradition.24 Chronicles and tales stemming back to Kievan times (generally composed by monastic authors) asserted that politics was based on love and friendship between the ruler and his elite. A chronicler quoted Grand Prince Vladimir I (ca. 980–1015) and commented:

“With silver and gold I cannot win a retinue, but with a retinue I can win silver and gold, just as my grandfather and my father won silver and gold with their retinues.” For Vladimir loved his retinue and consulted them about the administration of his land, about wars and about the law of the land.25

Muscovite texts perpetuated this trope. An early sixteenth-century chronicler put these words into Grand Prince Dmitrii Donskoi’s mouth as a deathbed peroration to his men:

You know my customs and my ways, for I was born and grew up before your eyes, and with you I ruled, and held my patrimony…. I had for you deep honor and love, and under you I held cities and great power; I loved your children, and against none of you did I do evil, neither did I take by force, nor did I offend you, nor subjugate you nor rob you, nor dishonor you. But I honored you and loved you and held you in deep honor. I shared your joy and your anguish, for you are not called my boyars, but the princes of my land.26

Secular documents also iterated these pieties. In his will of 1353, Grand Prince Semen Ivanovich instructed his heirs: “And you should not heed evil men, and if anyone tries to breed discord among you, you should heed our father, Bishop Aleksii, as well as the old boyars who wished our father and us well.”27 Several fifteenth-century wills also contained the warm sentiment addressed in Dmitrii Donskoi’s second testament (1389): “My sons, those of my boyars who take to serving my princess, care for those boyars as one man.”28 The 1550 law code states that boyars should be involved in the creation of new legislation; this was no constitutional guarantee but a statement of their traditional role of advising the tsar and sharing in his judgments.29 The implication of these sources is that the ruler should be open to all well-intentioned advisors, symbolizing his openness to all society. Exclusivity in power was condemned; full access to the ruler and harmony in the community was the goal.

Narrative literary texts also broadened the themes to create an ideal image of society as a godly community united in its responsibility to God and tsar. Texts that chronicled the Time of Troubles, as Daniel Rowland has shown, confronted directly the responsibility of ruler, boyars, and people. They depicted the realm as governed by pious advice and unanimous agreement, and they attributed the Time of Troubles to the breakdown of righteous communication—the rulers heeded evil counselors and thus fell into corruption, and the cowardly people failed to admonish and guide the ruler back to righteousness:

And because of the foolish silence of all the world when they did not dare to tell the tsar about the truth, about the destruction of the innocent, the Lord darkened the sky with clouds.30

Unanimity of ruler and people—through the mediation of spiritual and secular leaders—should prevail. This theme is constantly stressed in the Protocols of the 1551 church council. In a speech attributed to Ivan IV, he beseeches the church hierarchs:

Do not hesitate to speak in unanimity words of piety concerning our Orthodox Christian faith, concerning the well-being of God’s holy churches, concerning our pious tsardom, and concerning the ordering of all Orthodox Christian dominions…assist me, all of you together and in unanimity.31

In sum, rulers were expected to rule by God’s justice; to patronize the church; to be fair and devoted to the poor and to their men; to heed good advice from the church, the counselors, and the people; and to lead their subjects to salvation by pious example. A ruler is God’s ordained mediator between sacred and secular; in Daniel Rowland’s terms, social relations were “God-dependent,” with earthly mortals merely acting out their parts in the Christian drama of salvation. Social cohesion, in other words, was the product of Christian commitment.

In this context, the midsixteenth-century Agapetan elevation of the tsar’s image was a dramatic exception, even going beyond Agapetus’s intention. The conclusion of Agapetus’s Chapter 21 quoted above, for example, which praises the ruler as “like God, Master of all men,” makes clear the author’s distrust of exalting a ruler to excess:

Therefore as God, be he never chafed or angry; as man, be he never proud. For though he be like God in face, yet for all that he is but dust which thing teaches him to be equal to every man.32

This idea found resonance in sixteenth-century Muscovite texts as well: Metropolitan Filipp (d. 1569) used a full reading of Agapetus’s text to chastise Ivan IV, culminating with this challenge: “Or have you forgotten that you are also of this earth and also need the forgiveness of your sins?”33 A “God-dependent” vision of social cohesion and social relations was the dominant one in Muscovite sources.

The Muscovite consensus model of social integration appeared in nineteenth-century social thought, prompted by European organicist and Romantic visions of the premodern past. Whether with opprobrium or with approval, scholars and intellectuals as disparate as Petr Chaadaev, the Slavophiles, and “Western-izer” Hegelian-influenced historians such as Johann Ewers and S. M. Solov’ev presented pre-Petrine Russia as integrated and harmoniously unified.34 Proposals for a cohering central principle ranged from the social—Solov’ev’s kinship principle, rodovoe nachalo35—to the ideal—the Slavophiles’ celebration of Christian communalism (sobornost’) or Chaadaev’s condemnation of Orthodoxy as turgid and Muscovy as stagnant.36 But these were generally static visions of society. The social emphasis of late nineteenth-century historiography, in authors such as V. O. Kliuchevskii, S. F. Platonov, and A. E. Presniakov, addressed that weakness to some extent by examining the interaction of material and social forces in shaping the exercise of power. But a trend toward a social interpretation of autocratic power was cut short by the cacophony of competing visions of premodern “despotism” in the twentieth century. Only since the 1970s has some Western, generally American, scholarship been questioning the image of “autocracy” as total power and looking at the interdependencies implicit in premodern power structures.37 Here, I contribute to that discussion by examining the strategies the Muscovite government used to foster social cohesion. I find, paralleling the trend of theory, that those strategies used both coercion and consensus, and that cohesion can best be comprehended as a result of the reception and engagement in prescribed norms and institutions.

Coercive Strategies of Integration

In the Introduction, I stressed the minimalism of the state’s goals and activities and the fragility of its direct instruments of power. The diffusion of power discussed there—the conscious policy of tolerating regional and other pockets of authority and difference—was a strategy of social cohesion itself inasmuch as it reduced tension between state and society and conserved central resources for the exercise of power where it mattered most. Muscovy’s rulers—the tsar and his inner circle of boyars—chose their battles wisely, setting as their primary task the exploitation of the human and material resources of the realm. To increase those resources, they preferred extensive means (territorial expansion) to intensive (e.g., mining, patronage of improved agriculture and industrial production). In turn, they were forced to busy themselves with essential tasks, such as the cultivation of the elite, the expansion and modernization of the army, and the creation of networks of fiscal and political governance. Very traditionally, Moscow’s rulers also asserted judicial authority over the highest crimes, particularly those such as murder and theft, crimes which were seen as depriving the ruler of his just resources. As they undertook to unify their realm, tsars and boyars used strategies identified in modern theoretical literature: the considered use of violence; the inculcation of cultural hegemony through ritual and symbolism; and the provision of cultural practices, such as honor, that were open-ended enough to allow individuals to manipulate that discursive area for their own gain as well. In the next sections, let us examine these in turn, moving along the continuum from coercion to reward to ideology.

Quite rightly, recent social theory gives due emphasis—some scholars even give primary emphasis—to the underpinning importance of violence in maintaining social cohesion. There is no question that the Muscovite state used harsh violence systematically to attain its objectives when other means failed. The oft-quoted ravages of the Oprichnina represent an excess inasmuch as the sacking of Novgorod, the executions of boyars, and the rampages in the countryside accomplished no apparent goal and are universally condemned even by historians who venture to see some purpose in the Oprichnina as a whole.38 Plenty of examples of brute force, however, are to be found. Moscow, for example, invaded the city-state of Novgorod in 1478, arrested and deported much of the local elite, executed leaders of the anti-Muscovite opposition, and instituted direct rule by governors chosen from the cream of the Moscow boyars. The conquest of Tver’ in 1485 was equally violent, and that of Kazan’ and Siberia no less bloody; colonial authorities did not hesitate to use military force to put down the periodic uprisings in the Middle Volga and Siberia.

It should be noted, however, that Moscow also accomplished territorial expansion without resorting to extreme destructive force. Rostov Velikii and Riazan’ were added by marriage and inheritance, for example. Cowed by the conquest of Novgorod, Pskov capitulated with far fewer punitive consequences in 1510; even in Novgorod, the military annexation was preceded by repeated Muscovite attempts to secure Novgorodian loyalty without the use of force.39 The selective use of force acted prophylactically, exerting a threat that functioned as social control. The threat of violence was also embodied in the establishment of Muscovite garrisons at all key strategic points, even the most far-flung outposts of empire.

The political elite and rulers of Moscow also readily wielded violence against those of their number who threatened the political status quo. Tensions over succession to the throne came to civil war in the 1440s–50s. Thereafter, the rulers and boyars kept their potential rivals—grand-princely brothers, nephews, in-laws—under control by imprisonment and execution, as well as by more benign policies, such as forcible tonsure or the forbidding of marriages, thereby occasionally ending clan lines (the Mstislavskii clan, which died out in 1622, is the most eminent example). Boyars themselves resorted to violence when rulers were weak, as in the minority of the 1530s–40s and very likely in the Oprichnina, but such occasions were dangerous aberrations. As a rule, violence within the ruling elite was used in limited, specific formats.40 Tsars frequently put members of the elite in “disgrace” (opala), banishing them from the sight of their “bright eyes,” but the sanction was usually only for a day or two. Similarly, imprisonment for members of the elite because of precedence suits was brief (one to three days), an action more to inspire fear than to punish.

Muscovite rulers also used corporal sanctions to enforce the law in criminal cases. The death penalty was prescribed in the sixteenth century for recidivist offenders. In the 1649 Conciliar Law Code, a range of punishments from incarceration to beatings to execution was prescribed for criminal and civil offenses. In Chapter 1, we saw how prescriptions of corporal sanctions for insult to honor privileged social superiors over subordinates. Similarly, the threat of arbitrary confiscation of property was real for merchants and the landed elite, although relatively rarely invoked.41 Other examples of coercive measures to enforce social control include the state’s increasing involvement in the seventeenth century in enforcing enserfment by pursuing runaway peasants and its willingness to prosecute Old Believers—not for doctrinal errors, but for their perceived disobedience to the tsar’s authority (i.e., defying the tsar and avoiding taxes and military service). Again, however, one must add that once the precedent of the use of violence in the law was established, actual violence need not have been systematically meted out for the desired effect of social control. As we have seen in Chapters 3 and 4, sentences of corporal punishment for the elite were often rescinded, and sanctions for recalcitrant servitors often took the form of exemplary punishments—rituals of humiliation or brief imprisonment.

Given the great emphasis that has been accorded to the brutality of Muscovite government—stemming probably first from lurid descriptions of the Oprichnina in the contemporary European press42—the degree of violence in this state should not be exaggerated. Muscovy, like other premodern societies, chose strategies that were appropriate to the difficulties they faced (small elite, minimal bureaucracy, huge imperial territory, diversity of populace). These strategies included systematic and sporadic violence by officials; the threat of violence represented by administrators and garrisoned troops; the exercise of law and judicial institutions; and bureaucratic control, taxation, recruitment, and other means of resource exploitation. Muscovy used violence selectively and prophylactically as an example for the populace.43

Bureaucratic measures of social control were, after all, also coercive. They fall into Giddens’s “surveillance” category—that is, the systematic identification and registration of productive resources by the state. With the conquest of Novgorod, Moscow began cadastral surveys of populated lands in order to distribute land in conditional tenure; cadastres continued in newly conquered territories and in the aftermath of crises such as the Oprichnina, the Livonian War, and the Time of Troubles. Quite rightly, scholars have seen the registration of peasants in cadastres and subsequent prohibitions against moving from one’s registered community as a key step toward enserfment.44 At the same time, a central bureaucratic (prikaz) system was evolving that involved itself primarily in the registration of military servitors (the Razriad), foreign relations (Posol’skie dela), the provisioning of the cavalry (Pomestnyi prikaz), and the collection of revenues (the Prikaz bol’shogo dvortsa and its successors that collected taxes and customs revenues to support administrative and noncavalry forces). All these strategies integrated the realm by forcible subordination to the political power of the center.

Cultivating the Elite with Material Reward

Side by side with coercive measures that functioned negatively to prevent deviance, the state worked positively to attract the loyalty of its subjects. Material reward for the targeted elite was a particularly effective way to enhance cohesion; recall Giddens’s and Mann’s point that it was essential for premodern states to cultivate elites because elite power was essential for exerting local control and for enforcing central policy. The elite enjoyed a wide array of rewards, continuing traditions of governance by largesse, which I. Ia. Froianov—in an argument reminiscent of Georges Duby’s description of early medieval European kingdoms as based on gift-giving—has described as paramount in Kiev Rus’.45 So also in Muscovy. At ceremonial moments, such as the conquest of Kazan’ in 1552, the resolution of the Time of Troubles in 1613, and even the failed Crimean campaign in the 1680s, rulers lavished “fur coats, great French goblets and gold beakers,” “horses and weaponry,” “money and clothing,” and, of course, land on their loyal followers.46 More systematically, Ivan III (ruled 1462–1505) and his successors established the principle that the cavalry would be supported by grants of land in conditional tenure (pomest’e), to be supplemented with sufficient cash to purchase horses, weapons, and armor. A lesser level of privilege and reward was accorded noncavalry forces, such as artillery, musketeers, and new model infantry, as they were developed, in the form of tax privileges and access to communally owned land. At the same time, the principle was enforced that only cavalry members could own landed property—either in conditional or hereditary (votchina) tenure—with a few exceptions (the highest merchant and bureaucratic ranks and the church as an institution). The ultimate reward for the landed cavalry was enserfment of the peasantry, which provided the landed elite a steady means of support, even while its service obligations were being reduced and thus its raison d’etre was fading. Not coincidentally, enserfment was paralleled by a process of transforming de facto—and by the early eighteenth century, de jure—conditional land tenure into hereditary47

Government policy in the sixteenth century, and to a lesser extent the seventeenth, consolidated the landed cavalry elite territorially, as discussed in the Introduction. Janet Martin has argued persuasively that the mass resettlement of servitors to the Center from conquered areas (e.g., Novgorod, Viaz’ma, Pskov) and from the Center to the western frontier over the sixteenth century broke down regional loyalties and created the basis for reconstructed local communities with stronger loyalties to the tsar.48 Legislation on the devolution of patrimonial property had the apparent intent of creating and bolstering regional “corporations” of landed gentry by forbidding land to be sold outside of the members of a given region or extended clan. The creation of gentry control over local criminal affairs (the guba system) from the 1530s on similarly forged bonds of local association and connections with the center. In the seventeenth century, regional loyalties were further intensified as service requirements were decreased and local elites became adept at consolidating their patrimonial and service tenure lands in their home regions and monopolizing local offices.49

In the juridical realm, the practice of precedence (mestnichestvo) and the genealogical and service record keeping it entailed defined the privileged elite and worked to keep it circumscribed. The elite’s privileged status is also demonstrated by the law’s tendency to abjure corporal punishment for high-ranking persons and to diminish corporal sanctions for them when prescribed. Granted, these juridical tendencies did not constitute legal enfranchisement; no charter of privileges guaranteed their status. Winning a Magna Carta, however, is a high standard to set in defining an enduring elite; by other measures—access to political office, economic privilege, endogamy, and to some extent lifestyle—Muscovy’s landed servitors have the characteristics of other corporate, cohesive aristocracies.50

Institutional formats for integrating more and more individuals and families into the highest echelons of government also developed over the sixteenth and seventeenth centuries, thus expanding the benefit of the very generous amounts of land and cash awarded to the Moscow-based ranks. At the tip of the elite, one can cite the time-honored (going back to the fourteenth century) practice of grand princes marrying women from Moscow boyar families rather than from foreign dynasties. Even when, as was the rule in the seventeenth century, tsarist brides were chosen from relatively insignificant families, these brides’ clans were connected by clientage and marriage to more powerful cliques.51 A similar practice of building elite loyalty was the willingness of the boyar elite to absorb newcomers, provided they converted to Orthodoxy and intermarried with the boyar clans. Not only princes from the Grand Duchy of Lithuania (the Glinskie, Bel’skie, and Mstislavskie, for example), but also Tatar princes from Kazan’ (Tsarevich Peter in the first half of the sixteenth century), the North Caucasus (the Cherkasskie), and Siberia joined the Muscovite elite in the sixteenth and seventeenth centuries.

Access to the highest ranks of decision making, status, and reward—that is, the conciliar or dumnye ranks—expanded in these centuries as well, paralleling a general expansion of ranks and offices. From a handful of roles in a fundamentally patrimonial household administration, the court grew by the late seventeenth century to a clutter of largely honorific titles such as stol’nik, striapchii, and zhilets, each held by up to hundreds of men at a time; their main function seems to have been to spread the distribution of rewards all the more broadly.52 Until the mid-sixteenth century, there were fewer than twenty boyars or okol’nichie at the court. Growth was steady in the next century, with about twenty-five to thirty-five men in four conciliar ranks until midcentury, but by 1690, there were 153 men in the four ranks (fifty-two boyars, fifty-four okol’nichie, thirty-eight dumnye dvoriane, and nine dumnye d’iaki).53 Parallel growth in lesser ranks was even greater.54 These strategies served dual purposes. To some extent, they were a response to the increased need for administrative personnel in an expanding empire. But they also created a privileged Moscow-based elite that served as a magnet for lesser elites and as a broad basis of political support for autocracy.

Ideology Enacted Symbolically in Honor

Having moved down the spectrum from coercive mechanisms to the use of reward, we come to the realm of ideas and cultural practices that encouraged identification and cooperation with the community as a whole. These practices were based on the prevailing image of Muscovy as a “God-dependent” community; the idiom of expression was Christian. The Orthodox Church provided a cultural package of theocratic values, visual symbols, and rituals that provided a potentially cohering common belief system. One can debate the degree to which Orthodoxy was internalized in sixteenth- and seventeenth-century Russia—as in pre-Reformation Europe, practicing Christians in early Russia combined Christianity with an eclectic set of values and cultural practices and resisted attempts to reform the faith.55 Nor did it include non-Orthodox subjects. Nevertheless, the theocratic image of society as a community of believers and the ruler as God-ordained constituted one systematic code widely available for expressing political and social relations.

Another inclusive code that embraced non-Orthodox subjects was the protection of honor. Simultaneously, it promoted a discourse that encouraged behavior supportive of the status quo and provided practical opportunity for individuals to pursue personal needs or resolve local conflicts. Chapters 2, 3, and 4 demonstrated how individuals used litigation over honor to exacerbate long-standing conflicts or to catalyze tension into a cathartic resolution. The interactive “praxis” of honor gave honor dynamic power as a force of social cohesion. The theory of honor itself, however, also played such a role by focusing attention on the tsar as centerpiece of the whole society defined by honor. Reflecting on contemporary Muscovite ideas about honor, detailed in Chapter 1, we can see that honor encapsulated the ideal tenets of social behavior, at least from the ruler’s point of view.

To be honorable was to obey the laws, to respect one’s social status, to serve the tsar loyally, to revere God, and to live modestly and with sexual propriety. As I’ve suggested in Chapter 1, honor accrued to all subjects of the tsar, Orthodox and non-Orthodox, East Slavic and not. The only individuals who had no honor were those whose criminal behavior had in effect excommunicated them from the social whole: “thieves, criminals, arsonists and known evil men.”56 But the discourse of honor did not stop at enveloping individuals in the symbolic community of do-gooders. Honor had a concrete, physical dimension, which demarcated the parameters of the honorable community and located its center in the tsar himself. The spatial symbolism of honor in Muscovy transformed the concept of honor into a figurative glue binding all of society.

Far from being distinct from the social order, the tsar himself was its apex and its most honorable member. He claimed extensive protection of his own honor and bequeathed it to state institutions that patrimonially represented him. The tsar’s representatives and representations, although inanimate objects, could become subjects of litigation over honor. Documents, seals, and money became the objects of increased protections in the Conciliar Law Code of 1649 in its Chapters 2, 3, 4, and 5; this helps explain why a man was awarded compensation for insult to honor when he was called a minter (denezhnyi master, implying counterfeiter) and why officials were punished for inaccuracies or omissions in the tsar’s title.57 The tsar’s palace itself was deemed to have honor. For insults and assaults occurring in the tsar’s presence or palace, a twofold dishonor fine was levied, one for the insult to the individual and one for the insult to the tsar himself or to his physical representation, the palace (but the whole payment went to the aggrieved party). Similarly, churches were equally hallowed, enjoying increased fines for affronts on their premises.58 This is reminiscent of the honor attributed to physical location elsewhere: Thomas Cohen has argued, for example, that early modern Italian cities identified sites, such as certain palaces, as symbols of their municipal dignity and took affront when rivals mocked and desecrated pictures of that special edifice.59

The tsar’s honor radiated down to his representatives. Officials claimed dishonor when they were not obeyed in service or were treated disrespectfully. The Conciliar Law Code of 1649 made specific provisions to protect the honor of judges before whom litigants behaved impolitely. Judges frequently complained that they had been falsely accused of favoritism in the making of judgments.60 Dishonor suits arose when private quarrels broke out in front of judges and officials in Moscow chanceries or their provincial equivalents (s’ezzhie and prikaznye izby) or when litigants or subordinates directly insulted presiding officials.61 Similarly, as we saw in Chapter 3, officials sued when insulted in performing their duty in the army, as fire wardens (ob’ezzhie), or in local administration.

Because officials represented the tsar’s honor, their abuses of power were harshly punished, and individuals had the right to claim that abuse of power was dishonoring.62 Men complained of beatings or imprisonment by a corrupt governor or state secretary and of having been coerced for bribes.63 They were insulted when documents were falsified against them or when defendants or witnesses testified falsely against them; they found insult in an official’s favoring the other party in a suit because of enmity, corruption, or personal affiliation (svoistvo) or in an official’s improperly and maliciously enrolling a plaintiff in service in a regiment below his dignity.64 Most symbolically, the tsars jealously guarded the dignity of the Kremlin.

The Kremlin was a sacred space, its grounds and palaces marked as more and more hallowed the closer one approached the person of the tsar. Legislation from the midseventeenth century on defined with increasing hierarchy the physical limits of access to the Kremlin grounds enjoyed by various ranks. Only the highest ranks could ride into the Kremlin (others had to approach on foot), and even boyars had to dismount at some distance from the portico leading into the tsar’s palace. The courtyard closest to the tsar’s rooms was closed to all but specially authorized guards and confidants.65

The closer to the tsar one came, the more honored the space and the more privileged the individuals admitted to it. The tsar’s presence and quarters were therefore charged sites, where individuals felt all the more keenly any affronts to their dignity, particularly because they were surrounded by witnesses from equally exalted ranks. From Cathedral Square, privileged servitors climbed the stairway next to the Palace of Facets or Faceted Chamber (Granovitaia palata) to the Red (or Beautiful) Portico (Krasnoe kryl’tso). This was a narrow walkway off which were anterooms and a small Golden Palace (or Golden Chamber), with the Cathedral of the Annunciation (Blagoveshchenskii sobor) at one end and the Palace of Facets at the other. At the rear of the Palace of Facets was the Postel’noe kryl’tso (Tsar’s Palace Portico or Boyars’ Mezzanine), which was the largest staging area for courtiers in attendance. It contained the stairway by which the most privileged ranks could enter the rooms of the tsar.66 Courtiers were assigned to attend the tsar in the palace around the clock; incidents typically broke out at various staging points where courtiers gathered.

The Postel’noe kryl’tso and the anterooms of the tsar’s chambers were the frequent scene of hot words. In 1639, for example, Prince Ivan Araslanov syn Cherkasskii alleged that Prince Ivan Lykov assaulted him in the anterooms and insulted his whole family, while Lykov countered that Cherkasskii had insulted him and his family, calling them “insignificant princelings” “before the stol’niki, striapchie, and dvoriane” gathered there. Another case speaks of insult “before many eminent people” in a Kremlin courtyard.67 The publicity value that rivals got from the populated setting may account for the colorfulness of the slanders heard. In a case of 1643, a zhilets complained that another zhilets and his uncles had called him and his family “thieves, traitors, field hands” and had “chased my sons around the Beautiful Portico.” Witnesses reported that the plaintiff had responded by calling the defendants “sons of bitches” or “grandsons of bitches” and “little field hands” (stradnichonki).68 In 1646, a Prince Myshetskii alleged that at the Postel’noe kryl’tso, two servitors had called him and his family “slaves of boyars,” “sons of grooms,” “thieves, forgers,” while witnesses testified that the two servitors had called him “Prince Scribe” and his son “Prince Undersecretary.” Some complained of being called “drunkard” or “Prince Drunkard,” while others complained of their social status being denigrated.69

As seriously as servitors took affronts in the hallowed halls of the Kremlin, equally seriously did the tsar regard such incidents in his home. They were immediately investigated and punished harshly.70 The 1649 Conciliar Law Code decreed that for incidents in the tsar’s palace, a guilty party should be imprisoned for two weeks for verbal insult and for a month or more for physical assault, and should be executed for fatal blows.71 Cases bear out the principle of strict sanctions. In 1642, for example, a stol’nik was ordered “beaten with bastinadoes mercilessly” for insulting another stol’nik’s wife at the Postel’noe kryl’tso “as the tsar was walking from the Annunciation Cathedral beyond the gateway on the Feast of the Holy Trinity.” Perhaps because of the nearby presence of the tsar, the harshness of this sanction exceeded the later 1649 standards, which would have mandated imprisonment.72 In several cases, the letter of the law was followed: prison “for the honor of the palace” and a cash dishonor fee for the winning party.73 In others, norms were exceeded: In 1674, a striapchii was severely punished for hitting another striapchii in the head with a stone “at the sovereign’s palace in front of him, the Great Sovereign.” He was sentenced to be beaten with bastinadoes “instead of the knout” and to pay a fourfold dishonor fee, when the 1649 Law Code would have demanded long imprisonment and a twofold dishonor fee for such an offense.74

Such incidents also offered the tsar scope for bestowing his mercy, which he often did to spare a high-ranking servitor the humiliation of imprisonment, while maintaining the cash compensation to the victim, thus gratifying both sides. Such was the outcome, for example, of the 1692 case cited in Chapter 3 in which a family of the Golitsyn princes forgave a thousand-ruble dishonor fee. In this case, the tsar had already canceled the order to imprison the two Dolgorukii princes “for the honor of the palace” (they had insulted the Golitsyny in the tsar’s very chambers).75 In one case, the tsar reduced from beating to imprisonment a sentence for hitting a man with a brick in the Golden Palace or Chamber (Zolotaia palata), and in another, a man was ordered “beaten with bastinadoes mercilessly” and demoted to provincial service for resisting imprisonment, to which he had been ordered for saying “impolite words” in the tsar’s palace. “Not even in simple homes is it appropriate to say such things,” he had been told at sentencing. The beating was rescinded, but not the demotion.76

Insults in the tsar’s sacred space illustrate sharply the utility rulers and subjects made of the discourse of honor. Individuals chose that space to get the most effect out of their antagonisms; plaintiffs rushed to defend their honor before others; rulers exalted their dignity by punishing insults in their home with some of the harshest sanctions available, and they co-opted servitors with mitigating acts of mercy. The flexibility and manipulability of the discourse of honor for all its participants is dramatically demonstrated here.

Ritual and Ceremony

Symbolic communication and ritual were also wielded deftly to promote cohesion. Without making too sharp a distinction, one might distinguish ceremony from ritual by ritual’s more transformative power: While ceremony demonstrated political or social relations, ritual could catalyze and transform them. It had “an element of magic.”77 Both, however, constitute a language perceptible to members of the given society, and they serve as particularly important means of communication in societies in which orality rather than literacy predominated, as in Muscovy. Most court ceremony simultaneously communicated the image of the grandeur of the tsar and his intimacy with his boyars. Grand princes always appeared surrounded by advisors. Diplomatic receptions consistently described the ruler receiving envoys with the secular and sometimes the church hierarchy present78; in 1488, Ivan III is recorded as refusing to negotiate with a Habsburg envoy without his boyars present.79 Robert Crummey has argued that visual depictions of rulers and boyars—found in chronicle illustrations, scenes in biographical saints’ icons, and similar sources—depicted comradely, not distant and lordly, relations between them.80 Sixteenth-century Kremlin fresco cycles depicted the realm allegorically as a heavenly army, an image sure to appeal to the boyar elite.81

Receptions, banquets, and rituals at court seem to have become more frequent and lavish over the sixteenth and seventeenth centuries,82 most likely in response to the strains imposed by rapid political expansion in the elite and the empire. Karl Leyser argues, for example, that the tenth-century Ottonian court heightened its use of ritual as a response to perceived social crisis and in response to a decrease in the use of literacy at court.83 A similar strategy was at work in Muscovy: The challenges of building and administering an empire and managing its growing elite called forth, as we have seen, new strategies of governance, new institutions of social control, and new practices of social hierarchy such as precedence. Not surprisingly, new rituals were also devised in the sixteenth century to demonstrate power relations and integrate elite and people. Elaborate wedding rituals, with assigned roles for members of the highest elite, began to be recorded and replicated in Ivan Ill’s time; the ceremony of coronation was tried out in a moment of political crisis in 1498 and became a regular ritual from 1547.84 Over the course of the sixteenth and seventeenth centuries, grandiose liturgical rituals that brought the ruler and his elite outside the Kremlin gained currency; at Epiphany and Palm Sunday, the tsar, church hierarchy, and court elite processed in symbolic dramas that simultaneously acted out theological mysteries and demonstrated the political order.85

In addition to demonstrating political relations, court ritual experiences also engaged members of the elite and, quite pragmatically, gave more and more of them opportunity to participate at court. New honorific roles were created to enhance their participation, such as the custom (new in the sixteenth century) of stationing four men, drawn from the highest boyar families, around the tsar’s throne at audiences. Called ryndy, they wore white caftans and tall hats and carried ceremonial axes. Ritual displays of the elite certainly had the intent of impressing foreign visitors, who duly noted their awe at the splendor and size of the tsar’s retinues at court or lining the streets when they first rode into Moscow.86 But these displays also recreated the community in a cathartic way for its participants and potentially exerted a cohesive force.

Grand princes also regularly used ritual to engage the populace beyond the confines of the Kremlin elite. In processions of the cross, pilgrimages, and military campaigns, tsars acted out the hierarchies and bonds of a “God-dependent” community. In traversing their lands in a ritual manner, rulers “take symbolic possession of their realm,” demonstrating its “symbolic center”—that is, its leading ideas and institutions, to use Clifford Geertz’s formulation.87 Muscovite rulers were peripatetic. Their frequent pilgrimages took them to favored monasteries in circuits around the Muscovite heartland, sometimes extending as far north as Beloozero; hunting expeditions took them to summer residences in Kolomenskoe and elsewhere in the Moscow environs.88 During such outings, they distributed alms to the poor, offered amnesties to prisoners, dined with local dignitaries, and worshipped at local monasteries and shrines, thereby tangibly changing the communities they visited. The effect on beholders of such rituals and images is not recorded, and it undoubtedly varied among individuals. Some perhaps took it as imposed ideology, others might have been transported to greater heights of adulation and political loyalty. In any case, ritual was, in Edmund Leach’s phrase, “communicative,”89 and the message these rituals communicated was that the realm was united from tsar to peasant by Christian piety and humility.

A description of Ivan IV’s triumphant entrance in 1562 into Polotsk provides a particularly good example of symbolic communication through ritual. Polotsk had been ruled by the Grand Duchy of Lithuania since the fourteenth century, but it was once part of Kiev Rus’ and was now claimed by Moscow as ancient “patrimony.” The fact that the chronicle description may well embellish what actually occurred is less important to us than its idealized imagery of sanctification and community. Setting off on the Polotsk campaign in November 1561, the tsar began by establishing his links with legitimizing figures of the Muscovite past: He venerated icons and tombs sacred to the royal family housed in Kremlin cathedrals. Among the sites venerated were the ancient and revered icon of the Vladimir Mother of God (brought to Muscovy from Vladimir, but originally from Kiev) and the tombs of St. Peter and St. Iona (saint-metropolitans closely associated with the grand-princely family) in the Dormition Cathedral. He then visited the tombs of his ancestors in the Archangel Michael Cathedral across Cathedral Square. Then, with his male kin, the church hierarchy, and the court elite, he joined a procession of the cross on foot to the Church of SS. Boris and Gleb (saintly princes, patrons of the Riurikide dynasty since Kievan days) outside the Kremlin in order to venerate icons associated with his ancestor Dmitrii Donskoi’s victory over the Tatars in 1380. In doing so, he left the closed environs of the Kremlin for the domain of the people and thus broadened the social impact of his procession.

Ivan IV then took with him on campaign several revered icons, including a bejeweled gold cross said to have been housed originally in Polotsk. In January, in the recently conquered Velikie Luki on the way to Polotsk, on the eve of joining battle, the tsar took part in prayers and processions of the cross around the perimeter of the town. Going on foot to demonstrate his humility, he worshipped and dined in a monastery while the perfidious Grand Duchy forces fired on his party from across the Western Dvina River. When the city had been taken in February, the tsar entered on foot in a procession of the cross, repeatedly falling on his knees at the sight of icons and of cross processions sent to greet him, and heard the liturgy in the city’s main Orthodox cathedral. In the evening, the tsar feasted with his kinsmen and generals as well as with church hierarchs and military leaders from the conquered city, whom he favored with gifts in a gesture of reconciliation.

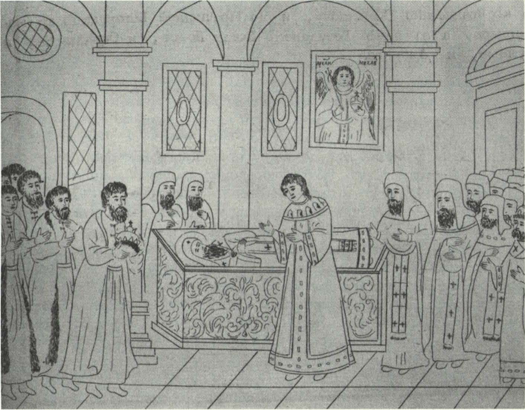

On the eve of his wedding, Tsar Mikhail Fedorovich is described as processing among Kremlin monasteries and cathedrals to pray at revered shrines. Here, in the Cathedral of the Archangel Michael, he venerated graves of his ancestors. (Illustration: P. P. Beketov, Opisanie v litsakh torzhestva, proiskhodivshogo v 1626 goda…[Moscow, 1810]. Courtesy Rare Book and Manuscript Library, Columbia University.)

Then the tsar sent word back to Moscow that he had regained his “patrimony” “with God’s help” and with that of SS. Peter, Aleksii, Iona (sainted metropolitans, especially patronized by the grand-princely family), and a list of more than twenty named saints associated with many regions of his realm (e.g., Novgorod, Rostov, Beloozero), thereby demonstrating Polotsk’s integration into the tsar’s dominions.90 He ordered bells rung in celebration in Moscow and services sung in thanksgiving and, in a show of largesse, sent gifts to the leading Moscow boyars and the metropolitan of the church. In a spirit of reconciliation, the tsar bestowed fur coats on more than five hundred Polotsk city leaders, giving them freedom to join his service or to leave to serve in the Grand Duchy. As the tsar returned home in March, he was welcomed by emissaries from Moscow at various points, where he stopped to worship or to banquet with his men and relations. Arriving in Moscow, he was met with a procession of the cross led by Metropolitan Makarii at the same Church of SS. Boris and Gleb from whence the tsar had departed. Here the tsar worshipped, gave thanks, and then entered Moscow on foot humbly with the procession. Throughout the account, Ivan is presented as God’s humble servant, as generous comrade to his men, as judicious protector of Russia’s heritage, and as benevolent ruler and reconciler. The symbolism of his activities stressed the (somewhat fictive) “organic” unity of Polotsk with Muscovy, drawing the new region into Muscovy by a combination of coercion, largesse, and historical symbolism.91

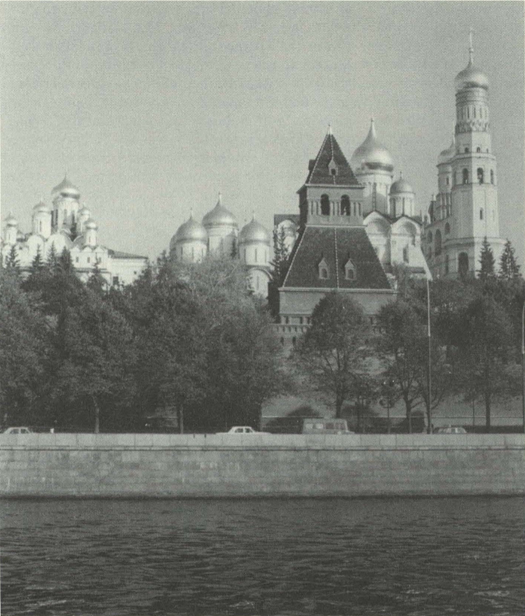

Muscovite rulers also defined the “symbolic center” of their realm with aggressive building projects. Ivan III (ruled 1462–1505) and Vasilii III (ruled 1505–33) transformed the Kremlin from an ensemble of mostly wooden structures to an exquisite stone ensemble, glittering with gold leaf and onion domes and magnificent in the magnitude and variety of its edifices. The new buildings demonstrated Moscow’s imperial conquests by including elements of Novgorod and Pskov architecture; they proclaimed Moscow’s cosmopolitan status with the Renaissance details on the Italian-built Archangel Michael Cathedral.92 And the centerpiece of it all, the Cathedral of the Dormition or Uspenskii sobor (1479), became a ubiquitous symbol of the legitimacy of Muscovite rule, not only because it was explicitly copied from the Vladimir Dormition Cathedral and thus symbolized historical continuity, but also because it became the canonical style in which grand-princely-patronized churches were thereafter constructed throughout the realm. Cathedrals copying the massive Kremlin model were built in Iaroslavl’ (1506–16), in Moscow at the Novodevichii Convent (1524), in Rostov (early sixteenth century), in Pereslavl’-Zalesskii (1557), in Vologda (1568–70), at the Trinity-St. Sergii Monastery outside Moscow (1559–85), and elsewhere. Grand princes also left visual images of their authority in the form of new churches and monasteries built to commemorate military victories (Sviazhsk, 1551; Kazan’, 1552; Narva, 1558) or to establish new centers of grand-princely patronage (Mozhaisk, 1563; Pereslavl’-Zalesskii, 1564). In this, Muscovite rulers were not alone: Sixteenth-century European rulers also assiduously disseminated their particular imperial style in architecture, iconography, and ritual to announce their power in their realms.93

The Kremlin ensemble established Moscow’s symbolic center. Its architecture symbolically co-opted the political legitimacy of the Grand Principality of Vladimir, demonstrated Moscow’s conquests of neighboring areas, and displayed Muscovy’s foreign contacts with its Italianate flourishes. The central Cathedral of the Dormition set an architectural pattern that was then disseminated throughout the tsar’s realm. (Photograph: Jack Kollmann.)

These ritual moments promoted both political legitimacy and social cohesion by “inventing tradition,” to invoke Eric Hobsbawm and Terence Ranger. They argued that nation-states build community by constructing myths and festivities based on history—accurate or generously interpreted.94 Here we have seen Muscovite rulers and ideologues, for example, consciously evoking or inventing tradition by calling on a pantheon of previous grand princes and by celebration of cults of saints particularly associated with the grand-princely family.95 Similar strategies, aimed at promoting territorial unity of the tsar’s lands, included the promotion of cults of miracle-working icons from the provincial hinterlands. These venerated objects were transported with special ceremony to Moscow, where they were copied and returned with equal fanfare to their hometowns. By such co-optation, such venerations created a sacral link between center and periphery.96 The church’s recognition of numerous local saints’ cults from the midsixteenth century similarly co-opted regional energies into the central community of faith.97 The process was also going on in narrative texts—a prime example is Metropolitan Makarii’s historical compilations, the Book of Degrees (Stepennaia kniga) and Great Menology (Velikie minei chetii), which situated Muscovy in the chronology of universal Christendom.98 Similarly, the proliferation of genealogical tales in the fifteenth century, of both the dynasty and boyar clans, mixed historical fact with “invented” traditions in the form of mythic ancestries dating back to ancient Rome. Celebrating a common past, even if a fictive one, gave a theory of community to a disparate realm.

Political Practices of Cohesion

Beyond the realm of ideas, Muscovite rulers supported a number of cultural practices that involved individuals directly in a dialogue with the established powers. One such practice was petitioning, the expectation that individuals could directly address the ruler with requests and grievances and that the ruler personally was the font of largesse and justice. The petition was the documentary form of all official bureaucratic requests for action. In their formulaic salutations and conclusions, petitions describe the personal relationship of individuals to the ruler: “To the Tsar, the Sovereign and Grand Prince of all Rus’ Aleksei Mikhailovich, your slave, the kinless, helpless Ivashko Pronskoi petitions…. Tsar! Favor me, kinless and defenseless! Do not order me to be in dishonor from such lowly people.”99 Through most of Muscovite history, individuals had the right to petition the sovereign directly, analogous to the “petitionary order” that Geoffrey Koziol describes at the heart of early medieval French politics.100 Only beginning in 1649 were Muscovites enjoined from giving petitions to the tsar, and the frequent repetition of this directive suggests how ingrained was the expectation of direct, physical access to the ruler.101 By the very act of transcribing one’s concerns in the form of a personal request for favor, individuals bolstered the pillars of autocratic legitimacy and also initiated processes that often satisfied their grievances.

Another social practice that emanated from the hegemonic discourse was consultation and collective judgment. As previously noted, in theory, Muscovite sovereigns were expected to consult the people, and the people had a moral obligation to advise the tsar. And in practice, rulers did defer to this expectation. In doing so, they paralleled consultative activities practiced by European rulers from medieval kings to absolute French monarchs; the practice, in other words, did not necessarily limit monarchical power.102 Usually this process of consultation was confined to the Kremlin: Tsars consulted their boyars or a smaller “inner circle” on day-to-day affairs; at ritual events, they were attended by the patriarch, other church hierarchs, and the assembled boyars in a symbolic demonstration of collective judgment. But it could be expanded to involve society: Tsars could instruct governors to assemble the populace and solicit complaints and petitions, which were then to be acted on locally by the governor or sent to Moscow for action. Or it could be done in more ritualized venues, as when the tsar formally summoned all his boyars and hierarchs to discuss such issues as his decision to be married (1547) or church reform (1551).

The logical extension of this mandate was the tsar’s summoning of a much broader social representation when the policy to be considered had a wider impact. Such large assemblies met sporadically from the midsixteenth to the midseventeenth century. They generally considered only one issue posed by the ruler, such as the settlement of war and peace, tax increases, or legal reform. Deliberation was collective, and consensus was the goal; these gatherings offered advice to the ruler, not a decision per se. Some assemblies were summoned with ample advance warning and called forth elected representatives from all social groups save the enserfed peasants; others were cobbled together from those servitors who happened to be in Moscow for muster. Surviving sources reflect the informality of this practice: Few such assemblies are documented by formal charters or records of deliberations, and some are known only from passing references in chronicles.103

Contemporary sources described only the process of assembling and consulting and did not label these activities with any collective noun, as later historians did (calling them zemskie sobory, or “councils of the land”104). These were not parliamentary institutions, as scholars, especially in the Soviet era, have construed them.105 True parliamentary institutions exhibited several key characteristics: fixed regularity of meetings; representative, not mass membership; multicameral structure; and real authority over legislation and/or the fisc.106 Lacking these traits, Muscovite assemblies nevertheless filled an important niche in the political structure.

Consultative assemblies like these offered arenas for political activity on many levels. Following Durkheim, they can be seen as cathartic rituals of communication, giving physical embodiment to the theoretical godly community of the realm and inspiring participants to identify with it. More tangibly, they provided channels of communication of central policy to the provinces and venues of acceptable challenge to government policy. Hans-Joachim Torke, for example, has chronicled how the government responded to some of the collective grievances advanced by gentry and merchants in the seventeenth century; Valerie Kivelson accounts how provincial gentry internalized the tenets of this political code and conducted political protest accordingly; Richard Hellie chronicled the role of the 1648 council in the compilation of the 1649 Conciliar Law Code.107 These assemblies were not merely top-down avenues of imposed ideology or empty ceremony. They were spheres in which significant contestation and negotiation could occur within the symbolic framework of consultative autocracy.

Many strategies, including the willingness not to interfere, worked together to create social stability in Muscovy. I should not exaggerate the degree of social stability that Muscovy achieved; like many premodern societies, it was a violent place. Most of the time, individuals related to the state in the unwelcome venues of taxation and recruitment or not at all. It was not a very admirable system, as few premodern systems would be to modern eyes. The state’s ability to control territory, people, and resources came at great cost—enserfment and the diversion of resources from high culture, education, and social welfare to the needs of war and the support of a privileged elite. This was a calculus with which most premodern rulers were comfortable, however. Accepting these ground rules, one can conclude that Muscovite society achieved enough cohesion to allow the state to accomplish its essential tasks. Cohesion came from a combination of factors: coercive control; tolerance of local autonomies; distribution of rewards; effective dissemination of unifying ideas in laws, texts, and ritual; and the ability of individuals to interpret and manipulate the dominant ideas and institutions to their own ends within bounds acceptable to the state.

Honor and its praxis provided a particularly potent means for individuals to pursue their self-interest within the framework of state-affirming institutions. By combining values that ratified the social totality and institutions sanctioned by the tsar with individual initiative, litigations on honor gave society an arena in which people and government both benefited. This connection should not be romanticized; individuals need not have liked the state to manipulate its values and institutions.108 But in so engaging with those values and institutions, they reinforced the dominant culture to some degree. Precisely because institutions of honor fostered a dynamic relationship between daily life and the normative consensus asserted by the dominant culture, they were one source of stability for Muscovy’s far-flung, multinational empire. They are emblematic of the flexibility that made autocracy viable in Muscovy: Autocracy worked not by isolating the ruler and his men in their power, but by involving society in the exercise of that power.

1F. G. Bailey, “Gifts and Poison,” in his Gifts and Poison: The Politics of Reputation (New York, 1971), pp. 15–16.

2Peter Burke provides a helpful overview of trends in social theory: History and Social Theory (Ithaca, N.Y., 1992), esp. chap. 3.

3Marx’s dialectical and materialist vision has continued to be advanced: Nicholas Abercrombie, Stephen Hill, and Bryan S. Turner, The Dominant Ideology Thesis (London, 1980).

4Horace M. Miner, “Community-Society Continua,” International Encyclopedia of the Social Sciences 3 (1968):174–80. See Anthony P. Cohen’s excellent critique of this concept: The Symbolic Construction of Community (London and New York, 1985), pp. 21–38.

5Emile Durkheim, The Division of Labor in Society, trans. George Simpson (New York, 1933); idem, The Elementary Forms of the Religious Life, trans. Joseph Ward Swain (London, 1915), esp. pp. 257–58. On Durkheim, see Anthony Giddens, Capitalism and Modern Social Theory: An Analysis of the Writings of Marx, Durkheim and Max Weber (Cambridge, England, 1971), pt. 2, pp. 65–118. A major exponent of consensus theory was Talcott Parsons: The Social System (Glencoe, Ill., 1951); idem, The Evolution of Societies, ed. and intro. by Jackson Toby (Englewood Cliffs, N.J., 1977); idem, “Social Systems,” in International Encyclopedia of the Social Sciences 15 (1968):458–73. See Ralf Dahrendorf’s critique of Parsons’s stress on consensus: Class and Class Conflict in Industrial Society (Stanford, 1959), p. 163. Parsons’s approach is explored in Lewis A. Coser, “Conflict: Social Aspects,” and Laura Nader, “Conflict: Anthropological Aspects,” in International Encyclopedia of the Social Sciences 3 (1968):232–42.

6Anthony Giddens, Capitalism and Modern Social Theory, chap. 11.

7David Forgacs, ed., An Antonio Gramsci Reader: Selected Writings, 1916–1935 (New York, 1988), chap. 6; Geoff Eley, “Reading Gramsci in English: Observations on the Reception of Antonio Gramsci in the English-Speaking World, 1957–82,” European History Quarterly 14, no. 4 (1984):441–77; idem, “Nations, Publics and Political Cultures: Placing Habermas in the Nineteenth Century,” unpubl. manuscript, 1990. Raymond Williams makes the same point in Marxism and Literature (Oxford and New York, 1977), p. 110.

8Max Gluckman, “The Peace in the Feud,” in Custom and Conflict in Africa (Glencoe, Ill., 1959), pp. 1–26, and his Politics, Law and Ritual in Tribal Society (Oxford, 1965). Victor Turner, The Forest of Symbols (Ithaca, N.Y., 1967); idem, The Ritual Process (Chicago, 1969); idem, The Drums of Affliction (Ithaca, N.Y., 1968); idem, Dramas, Fields and Metaphors: Symbolic Action in Human Society (Ithaca, N.Y., 1974). On these concepts, see Edmund R. Leach, “Ritual,” International Encyclopedia of the Social Sciences 13 (1968):520–26. Clifford Geertz, “Religion as a Cultural System,” in his The Interpretation of Cultures: Selected Essays (New York, 1973), pp. 87–125. See also “Deep Play: Notes on the Balinese Cockfight,” in his The Interpretation of Cultures, pp. 412–54. Anthony P. Cohen provides numerous illustrations of symbolic behavior maintaining community: Symbolic Construction.

9Foucault and Habermas are also keenly interested in cultural hegemony and the problem of power, but primarily concerning modern society: Michel Foucault, “Truth and Power,” in Paul Rabinow, ed., The Foucault Reader (New York, 1984), p. 61; Jürgen Habermas, “The Public Sphere: An Encyclopedia Article (1964),” New German Critique 3 (1974):49–55; idem, Communication and the Evolution of Society, trans. and intro. by Thomas McCarthy (Boston, 1979), chaps. 3–4. On Habermas, see Robert Wuthnow, “The Critical Theory of Jürgen Habermas,” in Robert Wuthnow, James Davison Hunter, Albert Bergesen, and Edith Kurzweil, Cultural Analysis: The Work of Peter L. Berger, Mary Douglas, Michel Foucault and Jurgen Habermas (London and New York, 1984), pp. 179–239.

10Sherry B. Ortner, “Theory in Anthropology since the Sixties,” Comparative Studies in Society and History 26 (1984):159.

11Michael Mann, The Sources of Social Power, Vol. 1: A History of Power from the Beginning to AD 1760 (Cambridge, England, 1986); Anthony Giddens, A Contemporary Critique of Historical Materialism, Vol. 1: Power, Property and the State (Berkeley, 1981), and his The Nation State and Violence: Volume Two of A Contemporary Critique of Historical Materialism (Berkeley, 1987). See also Charles Tilly’s Coercion, Capital and European States, AD 900–1992 (Cambridge, Mass., and Oxford, 1992).

12See a discussion of stability in early modern England in this vein: A. J. Fletcher and J. Stevenson, “Introduction,” in idem, eds., Order and Disorder in Early Modern England (Cambridge, England, 1985), esp. pp. 31–40.

13Agapetus, chap. 21, quoted in Ihor Ševčenko, “A Neglected Byzantine Source of Muscovite Political Ideology,” Harvard Slavic Studies 2 (1954), p. 147.

14David B. Miller, “The Velikie Minei Chetii and the Stepennaia Kniga of Metropolitan Makarii and the Origins of Russian National Consciousness,” Forschungen 26 (1979), p. 279; Ševčenko, “A Neglected Byzantine Source,” pp. 156–59.

15See Douglas Joseph Bennet, Jr., “The Idea of Kingship in 17th Century Russia,” Ph.D. dissertation, Harvard University, 1967, pp. 3–5; Ševčenko, “A Neglected Byzantine Source,” pp. 163–64; Miller, “Velikie Minei Chetii,” p. 279; on the Great Menology, see ibid., chap. 1.

16PSRL 21, pt. 2 (1913):610–11. All translations mine unless otherwise indicated. On this source, see also Ševčenko, “A Neglected Byzantine Source,” pp. 159–63; Michael Cherniavsky, Tsar and People: Studies in Russian Myths (New Haven, Conn., and London, 1961), pp. 46–49; Miller, “Velikie Minei Chetii,” pp. 336–37; M. D’iakonov, Vlast’ moskovskikh gosudarei (St. Petersburg, 1889), pp. 168–71. On the Book of Degrees, see Miller, “Velikie Minei Chetii,” chap. 2.

17Sigismund von Herberstein, Notes upon Russia, trans. and ed. R. H. Major, 2 vols. (London, 1851–52), 1:30; Giles Fletcher, “Of the Russe Commonwealth,” in Lloyd E. Berry and Robert O. Crummey, eds., Rude and Barbarous Kingdom: Russia in the Accounts of Sixteenth-Century English Voyagers (Madison, Wis., 1968), p. 132; Adam Olearius, The Travels of Olearius in Seventeenth-Century Russia, trans. and ed. Samuel H. Baron (Stanford, 1967), p. 173. For similar comments, see also Antonio Possevino, S. J., The Moscovia, trans. Hugh F. Graham (Pittsburgh, 1977), p. 9, and Jacques Margeret, The Russian Empire and the Grand Duchy of Muscovy: A 17th-Century French Account, trans. and ed. Chester S. L. Dunning (Pittsburgh, 1983), p. 28.

18The phrase is Olearius’s: Baron, ed., The Travels, p. 173. Marshall T. Poe, “‘Russian Despotism’: The Origins and Dissemination of an Early Modem Commonplace,” Ph.D. dissertation, University of California, Berkeley, 1993.

19For immediate predecessors to Petrine political thought, see Bennet, “The Idea of Kingship,” chap. 4, reprinted in Nancy Shields Kollmann, ed., Major Problems in Early Modern Russian History (New York, 1992), pp. 385–420. On political thought in Peter’s time, see Sumner Benson, “The Role of Western Political Thought in Petrine Russia,” Canadian-American Slavic Studies 8, no. 2 (1974): 254–73; A. Lappo-Danilevskii, “Ideia gosudarstva i glavneishie momenty eia razvitiia v Rossii so vremeni smuty i do epokhi preobrazovanii,” Golos minuvshogo 2, no. 12 (1914):24–31; Marc Raeff, The Well-Ordered Police State (New Haven, Conn., 1983); Cherniavsky, Tsar and People, chap. 3; Marc Raeff, “The Enlightenment in Russia and Russian Thought in the Enlightenment,” in J. G. Garrard, ed., The Eighteenth Century in Russia (Oxford, 1973), pp. 25–47; James Cracraft, “Empire Versus Nation: Russian Political Theory under Peter I,” Harvard Ukrainian Studies 10, nos. 3/4 (1986):524–41.

20See Larry Wolff’s discussion of eighteenth-century constructions of “Eastern Europe,” which includes Russia in the analysis: Inventing Eastern Europe: The Map of Civilization on the Mind of the Enlightenment (Stanford, 1994).

21A stellar example is the collectively written official history of the Soviet Union published by the Academy of Sciences in the late Stalinist years: Ocherki istorii SSSR, 8 vols. (Moscow, 1953–58). For discussions of Soviet revisionism within this canon, see James P. Scanlan, Marxism in the USSR: A Critical Survey of Current Soviet Thought (Ithaca, N.Y., 1985), chap. 5, and also his essay, “From Historical Materialism to Historical Interactionism: A Philosophical Examination of Some Recent Developments,” in Samuel H. Baron and Nancy W. Heer, eds., Windows on the Russian Past: Essays on Soviet Historiography since Stalin (Columbus, Ohio, 1977), pp. 3–23. Also relevant is Samuel H. Baron, “Feudalism or the Asiatic Mode of Production: Alternative Interpretations of Russian History,” in Baron and Heer, eds., Windows on the Russian Past, pp. 24–41.