Chapter 3

Why Explanations Fail

Blank stares: you've seen them before. Usually after you've spent the previous 10 minutes trying to make your audience, however small or large, as excited as you are about your idea. But it's clear from the looks on their faces that they did not get it. And when this happens, there's no way to move forward without leaving people behind.

I've been there. When I was a consultant, I prided myself on being able to explain technology, but I failed a number of times. My passion and interest caused me to speak quickly and skip important points. I sometimes assumed people were following along until I saw on their faces that they did not get the point.

Every day, many companies, homes, and schools are filled with blank stares and discouraged explainers. We all struggle to find the best way to communicate our ideas and we sometimes fail. We can solve this problem, but first, we need to identify the root causes so we can build a foundation for solving them later.

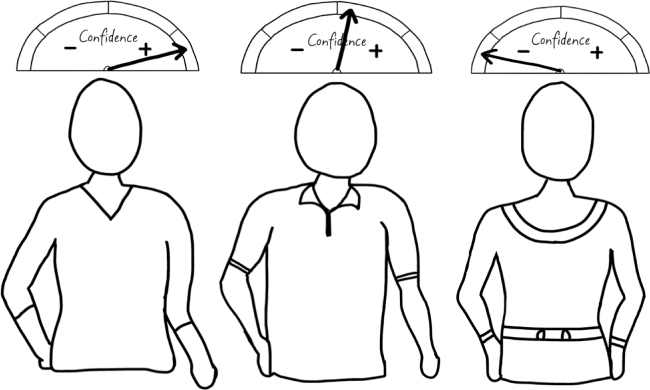

Those blank stares you see are a symptom of an underlying issue at the heart of why explanations fail. This issue is confidence, or the lack thereof. Blank stares often arise when someone has lost confidence that they can grasp—or should even care about—the idea you are communicating. And once confidence erodes, it is difficult to regain in that session. The audience essentially throws up their hands and focuses solely on “getting through” the explanation rather than fully understanding it. It can be a frustrating situation for all, and one that happens more than you think.

It can be easy to discern when an explanation is failing with a one-person audience. However, it can be more difficult to determine in a group meeting or classroom setting. For one thing, there are too many people present to gauge each one's engagement in your explanation. The real problem, however, is that you have no way of knowing each person's level of confidence in the material. For example, if your job is to explain type 2 diabetes to a large audience, it's nearly impossible to if they have never heard of the disorder before. What is basic to one person might be completely new information to another.

When you're faced with this, you must make assumptions about the confidence of the overall group, and inevitably, your assumptions will not match reality. This mismatch is common and probably the biggest reason explanations fail.

Of course, if we had a easy way to gauge every person's level of confidence in every subject, we might not need this book. For now, however, we have to make assumptions about the knowledge of people whom we may not know. And as we will see, we are generally not very skillful at doing so; therefore, we try to make up for it in other ways.

Why do we make such poor assumptions? To understand our problems in making assumptions, we can look at our decisions through the lens of the curse of knowledge, which is described in a book called Made to Stick by Chip and Dan Heath. The idea behind the curse of knowledge is that when we know a subject very well, we have a difficult time imagining what it is like not to know it. As we discussed previously, this is a matter of empathy. Our level of knowledge interferes with our ability to see the world from another person's perspective and gauge their confidence level accurately. We are cursed by what we already know. Here is an excerpt of an article by the authors from the Harvard Business Review:

In 1990, a Stanford University graduate student in psychology named Elizabeth Newton illustrated the curse of knowledge by studying a simple game in which she assigned people to one of two roles: “tapper” or “listener.” Each tapper was asked to pick a well-known song, such as “Happy Birthday,” and tap out the rhythm on a table. The listener's job was to guess the song.

Over the course of Newton's experiment, 120 songs were tapped out. Listeners guessed only three of the songs correctly: a success ratio of 2.5 percent. But before they guessed, Newton asked the tappers to predict the probability that listeners would guess correctly. They predicted 50 percent. The tappers got their message across one time in 40, but they thought they would get it across one time in two. Why?

When a tapper taps, it is impossible for her to avoid hearing the tune playing along to her taps. Meanwhile, all the listener can hear is a kind of bizarre Morse code. Yet the tappers were flabbergasted by how hard the listeners had to work to pick up the tune.

The problem is that once we know something—say, the melody of a song—we find it hard to imagine not knowing it. Our knowledge has “cursed” us. We have difficulty sharing it with others, because we can't readily re-create their state of mind.

In the business world, managers and employees, marketers and customers, corporate headquarters and the front line, all rely on ongoing communication but suffer from enormous information imbalances, just like the tappers and listeners.

—Source: http://hbr.org/2006/12/the-curse-of-knowledge/ar/1

For example, this scenario is common when new employees enter a company. They may have stellar resumes and related experience, but this cannot prepare them for the organization's communication culture. In meeting after meeting, they encounter successful businesspeople who seem to speak another language while assuming they are being clear. Acronyms, product names, and processes flow from them without hesitation. They are assuming the tune is clear, but all the new employees hear is tap-tap-tap.

So when you are doing your best to explain an idea and see blank stares, it could be the curse of knowledge at work. You are tapping along to a tune you know well and assuming the other people can hear the same tune. But in reality, they're losing confidence—and your explanation is starting to fail.

As we will see in the following and throughout the book, the curse of knowledge is an underlying cause of numerous problems in explanations, something that cripples our ability to make accurate assumptions about our audience. Thankfully there are antidotes for the curse that can help us create explanations that account for it and build confidence.

The curse of knowledge takes many forms. Consider, for example, the words you use every day in your job. Every profession, from medicine to woodworking, has its own language, and for good reason. We need this kind of specificity when we're at work; it gives us the ability to communicate with coworkers and peers without having to adjust for their confidence level. We can make accurate assumptions about the words they already understand because we work with them every day. Let's say that you work in the financial services field. You may use terms such as amortization, depreciation, and vesting so often you assume that everyone knows what they mean because pretty much everyone you work with does. The shared language becomes part of the workplace culture, and makes it more important and productive. However, it can also become a curse.

The more we live in a culture and use its own language, the more the curse of knowledge grows. Certain words and phrases become so common that we start to lose touch with how they sound to people who live outside of that culture. We may become prone to using a word like transmogrify or quotidian during a meeting or presentation and then wonder why there are blank stares when we use these same terms over dinner with our families.

A single word can make your explanation fail because it lowers confidence. One word has the power to move someone from interest to disinterest.

Think about it this way: you decide to get dinner at a new restaurant rumored to serve mouth-watering dishes. You open the menu and start to browse. If you are like most people, you're looking for dishes you either already like or would like to try. The menu's job is to be your guide, to serve as a resource that helps you make a decision with confidence. You narrow the choices to three dishes, and ponder the elements of each:

Although they all sound delicious, the third option feels like a risk. You have never seen the word rémoulade before, so you are not sure if you would like it. Therefore, you decide against ordering the entire dish because this one word made your confidence wane. You know that you love crab cakes and mushrooms, but the third part—rémoulade—moved you from interest to disinterest. It is an unknown element that represented a reason, in your mind, to move it to the bottom of the list.

This might seem like a tragedy to the rémoulade lovers out there, but it serves as an example for explanations: the words we use matter. In reality, rémoulade is a lot like tartar sauce, but sounds much more appealing and sophisticated on a menu. However, for the uninformed, it represents a reason to disregard an entire dish.

Explanations fail when we are unable to translate the language of our work to the language of a possibly uninformed audience. The curse of knowledge changes our perceptions and makes it difficult to make accurate assumptions about what others may know.

The curse of knowledge can be a privilege for some because it assumes that a person knows too much. But what about the other side of the coin? Knowing too little is an obvious problem when it comes to explanation. As Einstein once said, “If you can't explain it simply, you don't understand it well enough.” (BrainyQuote, 2012.) Being in the explanation business, I've learned that approaching an explanation without sufficient understanding is a quick way to dig yourself into a hole. The key to avoiding this situation is to set expectations.

For example, say you saw a news story about a new cancer drug that's coming onto the market. You're no scientist, but from the news story you get a pretty good understanding of the basics of the new drug. Because you're excited, you want to share the information. There is no harm in sharing—we all do it at times without fully understanding an idea. The problem arises when you position yourself as a knowledgeable person or use the word explain, as in, “I can explain it to you.” This gives your audience a signal that you have the information they need. Without realizing it, you've become an authority, which comes with a responsibility to make things clear and accurate. However, the news story gave you some surface-level information, but didn't provide enough to truly understand the drug. Of course, this will become abundantly clear once you've shared the facts you know and are asked for more information. At this point you're forced to admit you don't know the answers, or, even worse, you make things up to appear smart.

The key here is realizing that explanation means something to an audience and the word should be used with care. If you understand a subject and are prepared to answer questions, you are set up for success. But if you lack the understanding needed to converse about the subject and frame your ideas as an explanation, your lack of knowledge can easily be discovered and cause your explanation to fail.

There are experts in almost any profession—people who are known as leaders in a specific field. They write groundbreaking scientific papers, their art is respected by critics, and their companies flourish. We admire them and feel inspired by them. Although we may not know them personally, they are in the backs of our minds, constantly looking over our shoulders. We imagine what they would think of our work and would love a chance to earn their approval.

These individuals' impressive achievements motivate a number of professionals, which is a productive part of life. However, the need to appeal to experts also has the potential to make our explanations fail.

As Dipika learned, this is a poor trade-off in most situations. At heart, her presentation had potential; however, it was ineffective because its goal was to make her look smart, instead of helping others feel smart. This became the real lesson, and in the future, Dipika concentrated on impressing experts by her ability to help everyone in the room feel smarter.

Most people take explanation for granted. Because it's something we do every day in one form or another, we rarely take a step back and think about how we present an idea. When someone asks us, “How does that work?” or “Why does that happen?” we tend to answer the question directly if we know the answer. After all, it is efficient. Another person asks a question; we provide the answer to their question. It is usually a win-win.

The problem with this is that the direct approach can have an unintended consequence: the loss of confidence. Although their question wanted for an explanation, what they received was a statement of fact. Why does oil float on top of water in a glass? Relative density. What causes climate change? Increased CO2 in the atmosphere. Why does the ocean have tides? The moon.

Giving direct, accurate, and factual answers may seem to solve the problem from the perspective of the answerer. But in reality, it can shut the asker down. A statement of fact with no other context puts the onus on the asker to take the next step. If the asker isn't familiar with relative density or CO2, they are likely to move on rather than ask a follow-up question or probe for related ideas. Any hope of becoming a customer of that idea is lost.

This is a failure in the form of a lost opportunity. Although direct answers are often needed and well-placed, they do not work universally. A skilled explainer learns to see the intent behind the question and formulate an answer that focuses on understanding instead of efficiency. They answer questions like “What is this?” as if the question was, “Why should I care about this?” You can see this in play in the following example.

Sadly, the CEO probably did not have any idea what happened. From his perspective, he provided the most accurate and succinct answer possible. His priority was efficiency and he likely assumed it was effective. But it was not helpful at all from the engineer's perspective. In fact, it made him feel less confident that RSS was something he was capable of understanding.

Again, this is a lost opportunity. The CEO did not recognize that the engineer needed an explanation or that the direct answer he gave could actually cause more problems. He assumed that the direct approach would be the best way to answer and let him get back to his presentation. Had he heard “What is RSS” and answered a slightly different question, such as “Why should I care about RSS?” he could have helped the engineer feel confident. In this scenario, he could have replied “RSS makes it easy to subscribe to websites so that new content comes directly to you.”

This scenario unfolds every day in almost every company. We all answer questions; our challenge is to answer in the form that will help the person who's asking the most. Unfortunately, thanks to the curse of knowledge, we assume too often that the audience will be able to make sense of direct answers, when in reality, they usually need an explanation.

At heart, explanations are about affecting confidence. Good ones build it, and poor ones diminish or even eliminate it—and there is no shortage of ways to lose confidence. So what do we do? How do we address these problems and learn to build confidence through our explanations? The answer is simple: we start planning.