Chapter 4

Planning Your Explanations

A few years ago, my wife Sachi and I renovated our house. We saw an opportunity to transform it into a home and office. One of the first steps in this process was to spend time with an architect who gave us a sense of what was possible. This focus on planning meant that we could:

- Create and analyze the house's look and function

- Anticipate and account for potential problems

- Visually understand the big picture

This planning process helped the completed house become much more tangible to us. What was formerly a set of ideas with direction now had a form. We could begin the process of diving a little deeper into the details. Once we knew where the walls, windows, and doorways would be, we could think about lighting and electrical.

The need to have plans in construction is obvious: they save time and money. But what about in communication? How often do we sit down and focus on how we will explain an idea? What if planning our explanations could give form to our communications and yield better results, similar to those we enjoy when planning a home renovation?

This chapter will discuss the role of planning in building better explanations, and will introduce a model that will become one of our most valuable tools. We'll start by taking a look at the process of identifying problems because that is what plans do—help solve them.

Identifying Explanation Problems

Sachi and I came up with the idea of renovating our house after living there and seeing where design and function could be better. For example, the house's design of narrow hallways and small intimate rooms inhibited our ability to work together in the same room. We knew we could address that problem—and several others—through renovation.

Our lives as professionals are filled with potential problems as well. Some may be political: we can't move forward on a project without a boss's approval. Some may be financial: the company can't afford to do everything. Some may be technical: we don't have the tools or know-how to complete a particular project. Perhaps the biggest problem is time: there are not enough hours in the day.

Although most of us recognize the solutions for these common situations, there is another kind of problem that is perhaps more pervasive than any of those listed previously. It is so common that we do not realize it is there. It is the explanation problem.

An explanation problem is related to how we choose to communicate ideas. What makes an explanation problem so insidious is that it has the power to ruin the best, most productive, life changing ideas in just a few sentences.

A great idea, poorly explained, ceases to appear great, and the cost is tremendous. Let us consider the cost to the technology industry in the following example.

Meet Andre. He graduated from Stanford University a few years ago with a degree in computer science and is now focused on the company he started that he hopes will change the world. He and a handful of employees have been working on a product for more than a year now, and it is finally coming to life. Technically, it's an amazing product with the potential to positively impact millions of people—and Andre is finally ready to share it with the world.

Andre knows every detail of his product. He's prepared to answer any question and to speak about it with passion. After all, he's been able to overcome every challenge so far. His team of engineers solved the technical problems, his designers made it easy to use, and his investors, including a couple of angel investors, helped him overcome the financial limitations. If he can get a good start by word of mouth, the product is likely to spread virally from one person to another.

Andre's company finally arrived at launch day and the team was psyched. They were about to publish the website and announce the product to the world. All their work had come to this moment, and it seemed to go off perfectly. The first 48 hours were amazing. People were signing up rapidly and there was significant buzz online. It looked like things were going well.

But after the first month, new sign-ups leveled off and started to drop. Andre and the team were concerned; they started to analyze the data to determine why this was happening. The website hadn't changed, and the features were the same. What could it be?

The team decided to talk to some of the product's early users to see if they could offer additional insight. These users were a part of the product's tech-savvy market segment, and they were obviously excited about it. In fact, it seemed their excitement was contagious—just what Andre wanted. However, one thing became clear when interviewing these users: although they understood the product and its value well, they couldn't explain it in a way that encouraged others who were less tech-savvy to be interested. The excitement about the product's features was not translating to the people who could benefit from it. It was obvious that users weren't adopting the product because it was difficult to explain. Andre and the team could see that they had an explanation problem.

They had spent so much time and money developing the product and solving the financial and technical problems that they hadn't considered how to package the big idea of the product in a way that would help it spread from person-to-person. They assumed that it would be self-explanatory, with early users communicating its value to the rest of the market. However, the deeper they dug, the more they saw that the decline in sign-ups was because the product had only reached the initial adopters. Once that core group of users signed up, adoption stopped.

In some ways, this was a relief for Andre and the team because it provided them with evidence that the product was well-designed and the features worked. They didn't need to rethink the product; however, they did need to craft their communication strategy. How could their product make it from the inner circle of early adopters out to the mainstream?

At first it seemed like a marketing problem. Perhaps they needed to rebrand the product or change the copy on the website. They wondered if the tagline or the logo wasn't working. However, after considering those elements, it still didn't feel right. After all, early adopters were not going to change their communication style based on marketing terminology. The team needed to provide an explanation that accounted for everyone—not just the early adopters. In fact, it needed to be one that early adopters could use to help get others interested.

No one on the team had ever considered solving this important problem. How do you create an explanation that makes people care? They needed a plan.

Andre's situation is not unique to technology or to startup businesses. We all have ideas, products, and services that are often of high quality on their own merit. The problem we face is not one of features, design, or intellect, but one of explanation: how we relate the ideas to others. Without a way to explain something effectively, we limit its ability to spread.

Fortunately, we can all use the following simple model, called the “explanation scale,” to develop a plan for solving explanation problems. This model provides a way to visualize the audience, account for their needs, and move them from misunderstanding to understanding via a carefully crafted explanation. So let's take a look.

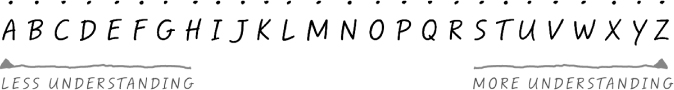

The simple A-to-Z continuum will be our guide to planning explanations. It is a simple way to think about moving your audience from one point to another. We will use this scale throughout the rest of the book to think about the transition from less understanding to more understanding of a concept. Therefore, it is important that we start with the big, basic ideas.

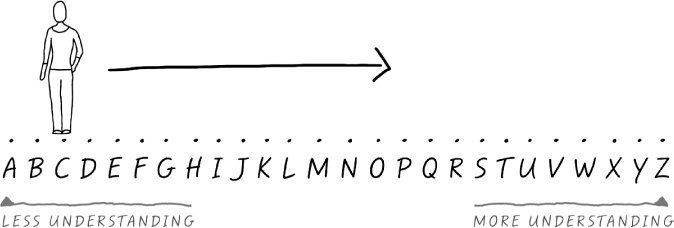

For example, the figure in the following is currently at “C” on the less understanding end of the scale. The arrow shows that our goal is to move her from left to right on the scale, representing her path to understanding an idea.

This scale is a part of the core of this book and is the instrument we use to map an explanation. We'll plot most of the ideas we discuss from this point forward on it, thereby creating a simple, memorable and visual tool for thinking about and planning explanations.

Back to Andre's explanation problem.

Andre's team has now identified that they have an explanation problem: their product's adoption is being limited by how it is being explained.

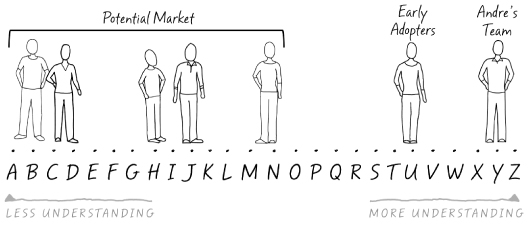

Therefore, the team decides to start with themselves. As the developers, they understand the product completely, so they plot themselves at the far right of the scale, around the “Y” mark. They've learned from talking to the early adopters that they also understand the product very well, and are far down on the scale as well—around the “U” mark. The scale looks like this:

It is clear that those who will be doing the explaining are very informed. They understand the product and feel confident about their knowledge. Of course, as discussed in Chapter 3, experience is not always an asset when it comes to explanation. It is likely that both Andre's team and the early adopters are suffering from the curse of knowledge: they know the product so well that it is difficult for them to imagine what it must be like not to understand it. The curse gets stronger the further you move towards “Z” on the scale, which can cause multiple problems.

First, the team is more likely to make incorrect assumptions about what people already understand. Second, early adopters are more likely to use technical language to describe features and benefits without adjusting for those with less experience. These factors may be the source of the adoption problem Andre is experiencing: the explainers are not accounting for those at the other end of the scale.

It starts to become clear for Andre: the people who understand and believe in the product are all the way at the right end of the scale—and everyone there has the curse of knowledge. At the same time, the market for the product is very broad; Andre sees that most of his potential users are all over the scale, from “A” to at least “N.”

Andre is able to use the scale to see the wide gulf between the people who understand the product and those who do not. He has to make assumptions about his target market. Because the product is meant to be mainstream, he must assume that the people in his target market fall everywhere on the scale of understanding.

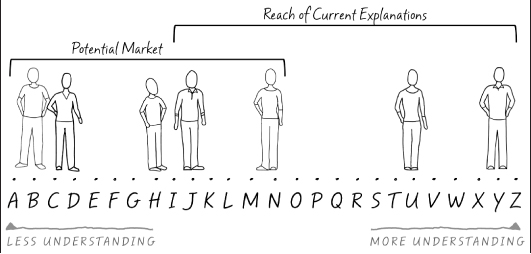

Andre must then consider the assumptions he and the early adopters have been making about people's existing knowledge of the product. Through discussions and interviews with current users, his team is able to get a feel for how the product is currently being explained. They use this information to decide that the current explanations assume that people have at least an understanding of level “L.”

From here, it is obvious what is happening. Thanks to the curse of knowledge, Andre's team and the early adopters are making assumptions—incorrect ones—about what people already understand. Their explanations appeal to the most informed of the target market, but leave the majority of potential users behind. As the following scale illustrates, the mainstream is not being reached by the current explanations.

Once he sees his market mapped along this scale, Andre understands that explanations were limiting his product's potential. He and his team had been working on it for so long they lost touch with the market and could not explain the product in a way that made potential customers feel confident that they could use it.

Now that Andre is aware of the explanation problem, his mind turns immediately to solutions—and some big questions come to mind:

- How do you know where to start an explanation?

- How do you account for people at every point on the scale?

- What ideas and tactics make explanations work?

- How do you get people down the scale?

In this context, I invite you to think about your own situation. Although Andre happens to be an entrepreneur, this scale serves as a way to think about almost any explanation problem that people encounter. Ask yourself the following:

- Where are you on the scale regarding a specific idea?

- Where is your audience?

- What assumptions are you making about their level of understanding?

- Are your current explanations accounting for everyone on the scale?

- Should they?

These questions are important because they frame perhaps the biggest problem in communication: we make poor assumptions about what people already know, and these assumptions limit the potential of our explanations. By using the explanation scale, we have a simple way to think about, talk through, and plan our explanations.

Next we'll look at how we can package our ideas into explanations that help us answer the previous questions and see how to think about building confidence via stepping stones that move the audience down the scale with confidence.

Explanations at Work: Albert Ni and 25 Million Views on Dropbox.com

In 2009, we were connected with a startup called Dropbox, which was looking for a video that would explain their product. The company was growing at an incredible rate and saw the potential for a short explanation to encourage more people to try the product. After using Dropbox and talking with the founders, we came to a couple of conclusions:

1. Dropbox is an amazingly simple tool that solves a real problem

2. It's very hard to explain. You don't realize you need it until you use it.

For us, this was a great challenge. We agreed to work with founders Drew Houston and Arash Ferdowsi on the video, not knowing how it would be used. In the fall of 2009, the Dropbox homepage was redesigned and featured our video as the main content. At the time of writing, 2.5 years later, the company has over 200 million users and the video is still on the Dropbox home page. According to Albert Ni, the former analytics lead at Dropbox, the video has been viewed about 25 million times. That's a lot of explaining!

Recently I spoke with Ni (who now manages multiple teams) about the video and what role it plays on the front page:

This is explanation at work. The Dropbox team realized that people coming to their website needed a way to understand Dropbox and get a “sense of how it could be useful.” I'm biased, but I think almost every technology website needs a video explanation doing this.