Chapter 5

Packaging Ideas

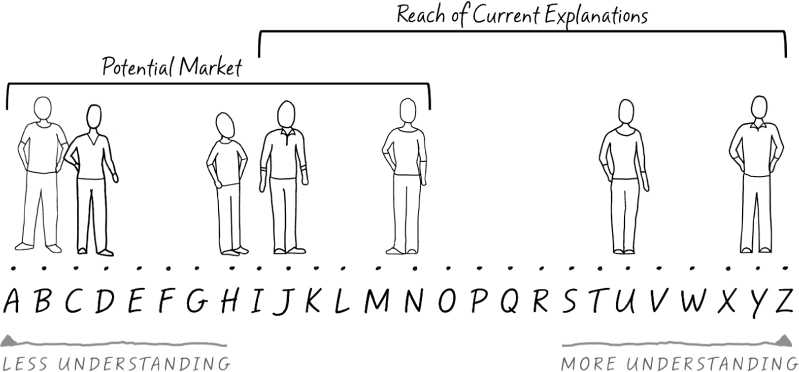

You have learned so far that explanation problems prevent people from understanding one another's ideas. Using the explanation scale, you learned to picture people who lack understanding on the “A” end of the scale. You know you need ways to move them closer to the “Z” end with confidence.

The second part of this book is dedicated to packaging ideas into explanations that can help you move people across the scale with ease. Many of these tactics were identified through making Common Craft videos, which we see as 3-minute packages of ideas. In creating more than 100 video explanations for companies and educators, we have analyzed and refined the main factors that make ideas easy to understand.

The idea of packaging works because packages have limits. Only so many things can fit into a package, and this is true with explanations as well. By packaging ideas into explanations, we define the package's contents by what we include or exclude. This gives our explanation form, shape, and limits. The idea is to identify an explanation problem and build a package that will solve it through explanation.

Below is the explanation scale that Andre's team used to visualize the reach of their current explanations. It highlighted a large group of potential customers on the “A” end of the scale who were left out because the curse of knowledge prevented Andre's team from accounting for their needs.

Stepping Outside the Bubble

Andre and his team have realized they need to package ideas into easy-to-understand explanations that start on the “A” end of the scale. But he has some concerns. He is a smart guy who works with smart people. As such, he prefers expressing his ideas in the industry's vernacular when he speaks, demonstrating his knowledge and intelligence. He believes it is an important skill for the leader of a company to exhibit.

When he thinks about explaining his product for someone at the “A” end of the scale, he worries that his message will be “dumbed down.” Andre has received little reward in simplifying his language and ideas for most of his life; in contrast, his professors and bosses encouraged him to flex his intellectual muscles. This context taught him to see dumbing down as a weakness—one that wasted time and could offend the experts whose respect you need.

This phenomenon is very common in both academia and business. You only need to read an academic paper or listen to the acronyms used in a business meeting to experience it. It does have value: industry experts need to communicate in their own language to relate specific and detailed information. For example, the medical terms used in an emergency department must be direct and specific to be effective. The same is true on an oil rig or in the kitchen of a restaurant. What often appears as complex communication is just deeply specific and meant for a narrow audience. And this kind of communication is understandable inside the bubble of expertise.

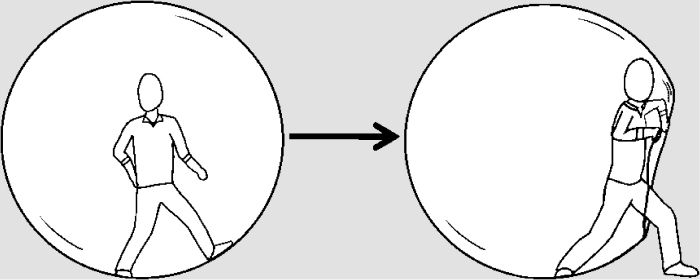

Andre notices his team developing an intimate language inside a bubble of their own as they're building the product. Their words, shortcuts, and acronyms have become common throughout their offices and cubicles. This intimacy of language has played a valuable role in interacting with each other efficiently. Because every team member is at “X,” “Y,” or “Z” on the explanation scale, there is no need to repeat the big ideas; everyone already understands them. This would be redundant and wasteful inside the bubble. But now that the product is almost ready for its mainstream audience, this communication style becomes a liability instead of an asset.

Andre imagines his team inside the product bubble, talking in the language they've developed. He then imagines his future users outside the bubble—people at the “A” end of the scale. This image helps him see that a big part of his success will depend on transforming ideas, concepts, and features from inside the bubble into a form that will make sense to these outside users. The membrane of the bubble is an important barrier for Andre and the team because they're likely to confuse people if they cross it without thinking. But if they can prepare for crossing it, they'll be able to step out into the real world using communications that help potential users feel confident and smart.

Andre realized for the first time that the bubble changes the fundamental way he and his team think about communication. Inside it, the team needs specificity, acronyms, and details; people are rewarded for using their communication to flex their intellectual muscles. This inward orientation rewards looking smart.

But everything changes outside the bubble. They have to rein in the need to look smart and they must think differently. To succeed here, they must focus on helping others feel smart. This idea was a revelation, especially to Andre.

The question becomes: how will they do this? Andre's team comprises mostly programmers and developers. They all see the potential, but aren't sure where to start when it comes to making their ideas easier and clearer for other people.

The answer for Andre's team—and for all people who want to make their ideas easier for others to understand—is packaging. They need to consider the potential to take a big idea or set of ideas and exhibit them in a form that solves an explanation problem for people outside the bubble.

What Goes into the Packaging?

Packaging ideas is a simple process that requires the person presenting ideas to account for the audience's needs. And because every audience and idea is different, there are innumerable ways to package ideas. However, they all focus on a few important elements:

Agreement—Agreement builds confidence from the very first sentence. It is accomplished through big-picture statements that most people will recognize. These are ideas about which you can say something like, “We can all agree that gas prices are rising.”

Context—Context moves the points we have agreed upon into a specific place. It gives the audience a foundation for the explanation and lets them know why it should matter to them. For instance, you could say, “More of your hard earned income is going to pay for transportation.”

Story—Story applies the big ideas to a narrative that shows a person who experiences a change in perspective and the emotions that accompany that change. “Meet Sally; she's tired of paying so much for gas and needs alternatives. Here's what she found.”

Connections—Connections often accompany a story and are analogies and metaphors that connect new ideas to something people already understand. “Sally could see that taking the bus was like multitasking because she could work and commute at the same time.”

Descriptions—Descriptions are direct communications that are more focused on how versus why. “Sally found that she could save more than $20 a week by taking the bus three times weekly.”

Conclusion—Conclusion wraps up the package with a summary of what was learned and provides a next step with a focus on the audience. “The next time gas prices get you down, remember…”

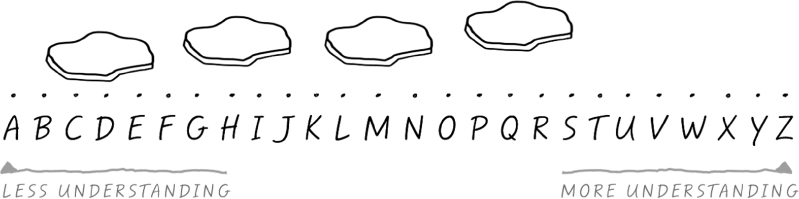

The examples above are high-level guidelines we'll explore more fully in following chapters. For now, it's important to think about these elements as stepping-stones in an explanation, with each step moving the audience from “A” to “Z” with confidence.