Chapter 13

Bringing an Explanation Together

Meet Emma, a human resources manager of a large clothing retailer. Her company is in the middle of a big change: they're transitioning every employee to a new benefits system with a high deductible health plan. Emma is heading up the team that's been charged with communicating this change to employees.

Although Emma has a great relationship with her colleagues, she's also nervous about this new program. She knows the details of the transition and can see it will be a positive change for almost everyone, but she's not sure how to ease this transition for the employees. Her goal, as outlined by the CEO, is to have 50% of all employees sign up for the new plan within six months.

After dozens of meetings with her team, they are finally ready for the rollout. They've crafted a set of e-mails that will serve as an introduction and invitation to join the new plan. The team agrees that the employees will want to know how it works, so they provide a couple of short paragraphs to explain the plan.

Dear Valued Employee,

Our company has a new health plan that will help us manage our health-care expenses and may lower your monthly health-care expenses. It's called the high deductible health plan. Here's how it works:

Your monthly premiums are likely to decrease and your deductible will increase from $500 to $1,000 when the new plan is implemented. This may help decrease your overall health-care expenses because deductibles are only paid when health-care services are used. If you and your family don't use health-care services, you won't pay deductibles at all, which means your overall expense is likely to decrease.

Emma gritted her teeth and clicked send on the e-mail designed to make the new plan easy to understand. And then…crickets.

She wasn't sure what to do. There were no questions or comments for the first few days, and to make matters worse, no one signed up for the new plan. Feeling puzzled, she assembled her team to assess the situation. Some members had done some reconnaissance work and discovered some useful but disappointing information: people didn't understand the change and didn't care about learning more. Some didn't know what a deductible was or why it mattered.

Despite her best efforts, she felt like a failure. Emma knew she needed a new path forward. What could she do?

When her team gathered the next week, one member named Carlos introduced an idea. He had been learning about explanation and informed the team they had a classic explanation problem. The new plan was beneficial, but people were not adopting it because of how it was being communicated. Carlos told them that it's a common problem and there are ways to plan and execute better explanations.

This idea took Emma by surprise. She had never thought about the new program as an explanation, much less considered how to improve it. She asked Carlos to come to the next meeting with a communication plan.

Carlos took the challenge and arrived at the next meeting with a few big ideas to set the stage. His goal was to help them see the potential of explanation as a communication strategy that could solve their problem.

To start, he asked the team about the last time they explained an idea, any idea, and used that to point out that we all take explanation for granted. As he said, “We do it all the time without giving it a thought. But what if we did think about it? What if we could improve our explanation skills? Do you think it would have a positive impact?” The team was intrigued; this had never occurred to them. Carlos could see the lightbulbs turning on and relished the proud smile from Emma. Everyone agreed: it was time to think differently about explanation, with Carlos as their guide. He and Emma hatched a plan for him to research and present his idea in a few days.

Soon Carlos realized a funny thing about teaching people about explanation—he had to walk the talk. He needed to explain explanation. Thankfully, he had started correctly by helping people come to an agreement on the potential of explanation. Everyone was on the same page; he just needed to take it a step further and ensure everyone understood exactly what an explanation is. This would help him build the team's confidence.

When the day finally arrived, Carlos began his presentation by making some factual statements. He stood at the whiteboard and wrote a few, including:

Everyone agreed that these statements were accurate and noncontroversial. In fact, they were the messages that every employee saw in the recent e-mail. Carlos then used these facts to distill the essence of explanation. He said, “The key idea about explanation is that it describes facts. These statements on the whiteboard are facts, and our goal is to describe them in a way that makes them more useful and easier for our colleagues to understand. And we'll do that by taking a step back and thinking about how to package them in a way that appeals to our audience.”

Carlos continued, “If we do it well, our communications will make people care about this new plan, and that's part of our goal. If we can make people care, they will become more motivated to pay attention and look more closely at the details. They will become customers of the ideas we're communicating.”

At this point Emma jumped in. “That makes sense, but it's a very tall order. Can we really expect people to care about a health-care plan policy change?” Carlos agreed it was a challenge, but he asked her to reserve judgment for a bit.

He had one other important point to make about explanation before moving on: “At the core of nearly every explanation is a simple question: why? Explanations may also cover who, what, where, when, and how, but the core question to answer is: why does this idea make sense?” Carlos then went to the board and added a simple word to each fact to set the stage:

These questions will help them frame their explanation.

“Now,” he continued, “it's time to think about the audience and identify the problems that keep our current communications from being effective.” Carlos then introduced two ideas for this:

He started with a quick discussion about explanation problems and used technology as an example. He asked the team if they used a couple of popular online services. Most didn't, but they were familiar enough with the services to understand where he was headed.

He then asked them, “How could these services enhance interest in using them? Through better engineering, better design, or a lower price?” These didn't really matter. “What about usefulness? Would it help if they were more useful to you?” Maybe, the group mused, but it would depend on purpose because they didn't know how to use the products in the first place.

“Exactly! These products have an explanation problem. Their adoption is limited by how they are being communicated. Being well-designed, potentially useful, and free is great; but unless the product can be explained, it's difficult for people to care about it enough to try it.”

He quickly connected this idea to the project at hand. “Our new health-care plan has an explanation problem, too. Despite being a good policy and a positive change for employees, adoption will be limited unless we can explain it better.”

The pieces were starting to come together. The team could see that something had to change and that the idea of better explanations made sense. But how? What could they do to improve their explanations?

Carlos proposed the first step to better explanations is to understand what makes them such a challenge, and for this, he introduced the curse of knowledge. Instead of diving in, however, he took a step back by asking the group: “Have you ever talked to someone who was very informed in a particular field—someone like a doctor, stockbroker, or mechanic—and felt like they were talking to you using another language? Did it seem like you needed a translator to understand?” Groans were heard around the room. Everyone knew the feeling.

“That's the curse of knowledge at work. These people are so steeped in their knowledge—they know so much about that particular field, be it medicine or finances or cars—that they've lost the ability to imagine what it's like not to know. Their language sounds natural to them and their peers, so they assume everyone else understands, but unfortunately, they don't. The curse prevents them from altering their language to account for different audiences. And we all suffer from the curse in some way. Everyone sitting in this meeting has the curse of knowledge for HR subjects. Therefore, to give better explanations for those outside of our department, we will have to keep our language in-check.”

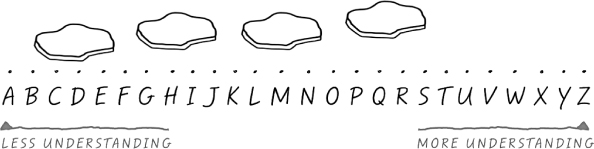

To make his point, Carlos headed to the whiteboard and drew a simple scale from “A” to “Z.” He wrote “Less Understanding” on the “A” side and “More Understanding” on the “Z” side.

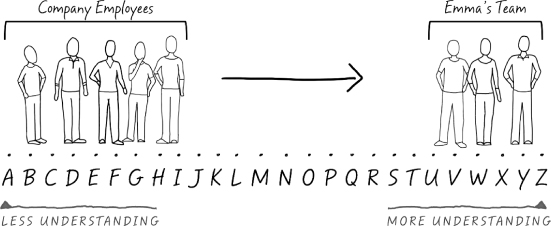

Carlos said, “This is the Explanation Scale, which we can use to help us think about our explanations. Right now, this team is at the ‘Z’ end of the scale. We know the new plan very well. The company's employees are at the ‘A’ end of the scale. They don't have a strong understanding of the new plan.

“Our goal is to create explanations that move them to the right—toward the ‘Z’ end of the scale.”

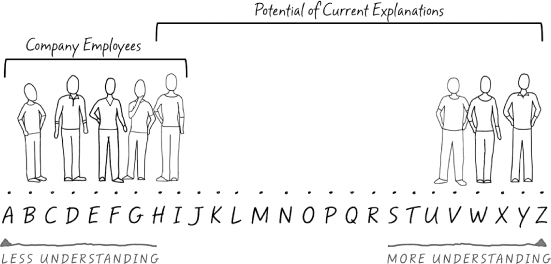

“One reason it's not working well now is because we're all so far on the right end of the scale. It's hard for us to imagine what it's like not to know about the new plan. We're forced to make assumptions about their existing knowledge, which influences how we communicate. It could be that we assume we're reaching everyone, when our communications are only reaching to those at the ‘G’ level—leaving most employees in the dark.”

This affected Emma, who couldn't stop thinking about the e-mail she sent weeks before. What assumptions was she making about the employees, and where would that message appear on the scale? Could the curse have caused her to miss the mark in her communications?

The goal became clear for the team: to create an explanation that accounted for everyone on the scale and to use explanations to move them to the right. But the big question still remained: how? How could they create an explanation that did just that?

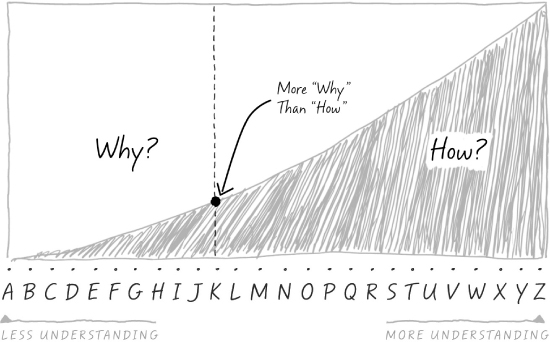

Fortunately, Carlos was ready to answer that question. He referred back to the explanation scale to make a quick point. “Here's one way to think about the needs of people at different points on the scale.” He drew a simple dividing line and added two words—why and how, like this:

He described how he could plot the team's approach to explanation on this curve, with the idea that explanations need a combination of both why and how. For example, someone at “C” needs more information about why the new plan makes sense. Someone at “R” is probably informed enough to understand why, however, and needs more specific information on how it works.

Carlos connected this idea to the statements he wrote on the board at the beginning of the meeting by saying, “Imagine someone at the ‘A’ end of the scale and think about the facts we discussed previously. This person needs to see the why before the how. And just like we discussed, it's a simple matter of describing the facts by asking the question: why does it make sense that it works this way?”

After everyone reconvened after lunch, Carlos drew the following simple picture on the explanation scale and asked the team to think about the new policy from this person's perspective:

He explained how the new policy appeared from an average employee's perspective: “Think about how this change looks to an employee. It's big and unwieldy. It takes time to understand, and our colleagues have more pressing things to do during a busy day. The cost of figuring out the new plan is high for them; and since they can't afford the investment, they tune out.” The team nodded in agreement.

He then turned to the problem's solution and said, “That's why we have to offer them an invitation to learn that helps them feel confident and provides stepping stones to learning more. What if we could present the new plan so that instead of seeming monolithic, it seemed more like this?”

Suddenly, the path forward became clear. Their explanation would be organized by steps, leading the person from the “A” side of the scale to the “Z” side.

Emma wasn't completely convinced, however, and had a question. “I think this makes sense, especially for people who know very little. However, a good percentage of our employees are actually toward the middle of the scale. Aren't they going to be turned off by all the introductory information?” It was a good point: this approach did appear to focus only on the beginners.

But Carlos was prepared and able to help her see it differently. “It's true that this approach does account for people at ‘A’ who have very little understanding; but we must start there to capture every employee. And yes, this means that those in the middle of the scale will hear about information they already know. But the question becomes: would you trade one for another? Does it make sense to orient the start of the explanation at ‘L,’ knowing a group of beginners will be left behind, or start at ‘A,’ knowing people in the middle will find it a review?” Emma thought about that for a minute.

Carlos put the question in a different context. “Think about it in terms of cost. What costs more, leaving beginners behind, or reminding the informed?” That made sense to Emma. An explanation that starts at “A” will simply validate the ideas of those who already know the subject and give them a bit more confidence in it. But the cost of starting beginners at “L” is very high because those at the left end of the scale are cut out completely. Only by starting at “A” could they help everyone feel confident.

The group felt satisfied and ready to move on. They understood the underlying concept: they needed to account for people at “A” on the scale and to provide stepping stones to move them to the right. But what were these stones?

Carlos could feel his excitement building as he went on. “This is where an explanation really comes together and where we have to think creatively. There are many ideas we can provide as stepping stones, and the right combination is different for every situation. There is no specific formula; it's more of an art.

“And thankfully,” he continued, “getting started is easy. Our goal is to invite those at the ‘A’ end of the scale to feel confident, which requires us to build context. This will help them see the big picture, and then the details will make more sense to them. We want them to understand the forest first and then the trees.

“Let's say we pick an important part of the new plan, such as coverage for family members. You could say this is a tree. It's important and helps the person understand a single idea. But that tree becomes much more valuable if we take time to talk about the forest first. It's part of a bigger picture and so allows the person to see the tree in the context of all the other ideas—the forest.”

Emma recalled the e-mail about the plan she had sent and concluded that it was essentially a set of trees—ideas that existed without context or foundation.

“We can start to build context by making a few statements that are factual and not controversial. We want everyone to be able to feel confident. We could even frame this as we-can-all-agree statements.” Carlos provided some examples.

We can all agree that…

“As you can see, these statements accomplish a few things. First, they create an easy initial step that can be understood with confidence without complex terminology. Second, they frame the direction of the explanation: it's about health-care plan costs, something that impacts everyone. Third, it creates a foundation for future ideas and/or goals. We're starting to build the forest.”

The team was excited about piecing together this communication puzzle.

“Next we'll focus a bit more and present a big idea. For now, let's say it's something like: To help ensure everyone's health-care expenses are manageable in the future, we're switching to a new plan called the high deductible health plan—and this message will help you understand what that means.”

He continued, “As you can see, here we've focused on the big idea and assured our colleagues that our intent is to make it easy to understand. We've given more context and therefore more confidence. Note that we're still at the ‘A’ end of the scale, with the priority focused on the question why; we'll get to how later. The question we need to keep in mind is ‘why does this make sense?’ ”

Carlos then challenged the team to brainstorm the answers to this question. Why does it make sense that the new plan will help employees manage health-care expenses in the future?

After some discussion, a few big ideas emerged. The best one came from a mid-level manager who described the situation as follows: “With the old plan, people were paying for health-care whether they used it or not. This new plan means they can save money because cost is connected to use. Your costs can go down if your family is healthy, and that couldn't happen before.”

This claim elicited some emotional reactions. The health-care plan manager immediately shot back “That's an oversimplification; it's true for some, but not for everyone. There are a number of important exceptions and I'm not sure we want to set that expectation.” Everyone could see that she had a point, including Carlos. But he was prepared for this argument.

“I think you make a valid point. However, it's crucial for us to make the overall concept absolutely clear. We're still talking about the forest and we want people to feel confident. We'll talk about the exceptions and details in a bit; but our goal for now is to be certain that the big idea is clear for people. Otherwise, the details won't make sense.”

They decided to stick with a very similar statement: Up to this point, your monthly health-care expense was constant, whether you saw a doctor or not. This new plan means that your health-care expense may change based on your family's use of health-care services. When you and your family are healthy, your monthly expense can potentially decrease.

From Carlos' perspective, the explanation was on the right track. The group was able to recognize that the big hairy idea of the new plan was too overwhelming to discuss at first. They had to get to its core and make the value easily visible. Although some team members had valid concerns, they were slowly becoming oriented to this approach.

As a reminder, Carlos went back to the whiteboard and illustrated the progress so far. He estimated that they were at about “J” already.

The forest was in place and it was now time to introduce some of the trees and make some choices about what stones to use. Carlos pointed to the scale.

“So far so good. We've accounted for those who had no understanding and now they can see the big picture of what we're communicating and why. We're now at about ‘J,’ and our next step is to head toward specificity. But first, we need to make some choices about the next stepping stones. There are a number of options we could consider at this point; we could even combine a few of them.”

He continued, “The two most common options are to tell a story or make a connection—and we can do both. Connections are often analogies that connect a new idea to something the person already understands. Stories follow a person's experience in learning about and trying a product or service.”

“From my experience, connections are a great starting point if the big idea still isn't clear.” Emma was pleased.

Carlos encouraged everyone to come up with ideas that were not related to health care but that operated like the new plan. They had to be common concepts with which everyone was likely to be familiar. “The idea here is to say ‘you know how this works, right? Well this plan is very similar to it.’ ”

A team member tried to clarify. “So we're saying that the old plan was a subscription with a constant price and new plan is also a subscription, but costs less when it's not used, right? Maybe we can think about things that come with subscriptions or memberships? Maybe newspapers and magazines? What about health club memberships?”

When the team got too concerned with details, Carlos reminded the group that the connection has to make sense; however, it can operate with an unrealistic assumption to make a point.

“For example,” he pointed out, “the magazine concept could work. Let's say that you have a magazine subscription that you paid for every month whether you read it or not. But now the magazine publisher offers a new plan where you pay less if you don't read very much of it.” Carlos recognized that it was a clumsy example. “I understand it's not realistic, and would never happen. But does that matter? If it makes our point and helps people feel confident, I think it should be considered. The question is, does this connection help people see the big idea of the new plan in a clear and accurate way?”

The team was split. They decided to go ahead and draft the idea with the recognition that it may be edited or removed.

Here's one way to think about the new plan. Let's imagine that you subscribe to a magazine. Some issues you read from cover-to-cover; others go straight to the recycling bin. Under this system, you're paying for issues that you don't use. Now let's consider a new plan in which the magazine's price is based on usage. You still pay a subscription fee, but that fee decreases in months when you don't read it. This way, you can save money when you don't use it. Our new plan is similar. It's built around the idea that your expenses should decrease when your family is healthy. It just makes sense.

Carlos then suggested that they use a story. The team looked skeptical and Carlos smiled. He had seen this coming because he had the same reaction when he first heard about stories in explanations. To help get everyone oriented, he explained that stories take many forms. Some are very developed and complex, but others, like the kind the group will use, are much simpler and become a way of relating facts in a form that makes them more meaningful.

Carlos said, “By simply adding a person's experience to a set of facts, we can create an experience that appeals to people and informs them without an extraneous backstory. Think of it this way: instead of fact telling, we'll be storytelling.” The team still wasn't convinced, so he provided an example.

Carlos walked across the room, grabbed a stapler and said, “Let's talk about the facts of this stapler. It's made of metal. When pressed, it produces a staple. Staples can be used to connect pieces of paper. Staplers are common office supplies.” He continued, “This is fact telling; I'm sharing some useful facts about staplers.”

“Now let's talk about storytelling, which takes the facts and packages them into a different form. For example…meet Marvin, an office worker. His job fills his desk with papers that he often misplaces. But now that he has a common office stapler, he can organize the papers by stapling them together with one easy press. This simple metal device helps him be more efficient and impress his boss.”

The team got it. They didn't need to know Marvin's backstory or career goals, or follow him through a set of challenges. All they needed was to see the stapler through Marvin's experience.

Before diving into the story, the team talked about what it should cover and decided that it could be powerful to show how two different people may experience the new plan. This would allow them to provide a little more detail. They decided to describe a family who is healthy and saves on health-care expenses, compared with another family who needs to see doctors more often. With Carlos as their guide, these stories took shape…

To see how the new plan may impact your family, meet the Smiths and Johnsons. These two families have a few things in common. Both have two children and a parent employed by our company. They even live in the same neighborhood. Both families need health insurance, and, like everyone else, have seen costs rise over the years.

The Smith family has been very lucky. The children rarely fall ill and only visit the doctor for annual physicals. Mrs. Smith has had her insurance premiums go up over the years and felt that, although insurance was necessary, it was a little unbalanced because her family didn't use much health care.

The Johnsons were not as lucky. One family member has a chronic illness and they rely on health insurance to make care affordable. They hate to see premiums rise, but it's better than paying out-of-pocket because this would cause them to go into major debt.

Now that the company has a new health plan, both families want to understand what it will mean for them. Apparently, monthly premiums will decrease and deductibles will increase. They can both see that it's a balance—that savings on a monthly basis may go to deductibles if they see a doctor.

Mrs. Smith feels good about the plan because if her family's good health continues, her premiums will reflect less usage. Although the cost may be higher when they do see a doctor, they can put away the savings in premiums each month and possibly have this extra money by the end of the year.

Mr. Jones is also happy to see lower monthly premiums. The deductible may be higher, but he realizes that his family needs more care than most. And because the coverage isn't changing, he can continue to depend on the insurance.

As you can see, the change in health-care expenses with the new plan will depend on each employee's health-care needs. The result is a new balance of higher deductibles and lower premiums, one that creates a money-saving opportunity for many families. And, it helps ensure that the company can also afford to offer a plan that makes sense for all employees.

The team was excited as they finished this exercise. They'd managed to bring the new plan's boring policies to life through a story. They couldn't imagine trying to use fact telling to communicate with employees when this approach made so much more sense.

The pieces were starting to fit together. Not only was the team thinking differently about explanation; they now had a solid start on an explanation strategy. They had a way to make a connection to an idea everyone knows well and a story that makes the facts more understandable and usable.

As a final exercise, the team needed to think about how these ideas would be presented. Could it be accomplished through e-mail? What about a presentation? Could they make a simple video or visual of some sort?

Carlos asked Emma for a few days to get prepared to answer these questions.