Chapter 15

Right Medium for the Message

Have you ever wondered about the lack of cooking shows on the radio? They exist, but are few for a very simple reason: this medium is not the best fit for the message. Radio is an auditory medium and cooking is best when it's visual, or even better, live. This mismatch highlights a crucial idea: medium matters.

One of the keys to getting the most out of an explanation is being deliberate about the media in which you choose to present it. It's easy to fall back on sending an e-mail or creating a PowerPoint presentation with bullet points—and who knows, it might be effective. But looking at all of our media options allows us to move beyond something that simply works and instead formulate explanations that are remarkable and sharable.

Explanations, by definition, are meant for sharing. In isolation, they wither and die. This chapter is devoted to giving your explanations an opportunity to flourish and potentially, live forever.

As we discussed earlier, explanations often enter the world in the form of text. After planning and packaging ideas, we write an explanation to capture the major points. These written explanations are much like a screenplay for a movie or the Common Craft video scripts we've included in previous chapters. The written word is a simple and accessible way for us to explain an idea and communicate it to others. But text is just one of many options for conveying our message to others.

You have multiple options at your disposable for how you can present explanations; so many, in fact, that it can seem daunting. Do you use images, text, audio, or video? Do you put those media into presentation software? An infographic? Webinar? How about recording and sharing it? Can you capture the presentation in a way that makes it useful anytime, anywhere?

These are very important considerations, because—as we addressed at the chapter opening—the medium is likely to help shape the message. The choices we make will influence how the audience will perceive and use our explanation, and even the best-written explanation can fail if we choose poorly.

Before diving in, I think it's important to set the stage because the world of media can be very complex. Media are often combined across platforms and contexts, creating infinite combinations and opportunities. For example, a simple video may include text, visuals, and audio or combinations of each.

As much as I would love to provide a method for matching the perfect media with every situation, it's just not realistic—or possible—to do so. Media decisions aren't and shouldn't be prescriptive. Your audience and access to tools are unique to you and the explanation you're crafting. Therefore, the best path forward is to share a range of options and show you how to approach the process in a way that aids your decision-making.

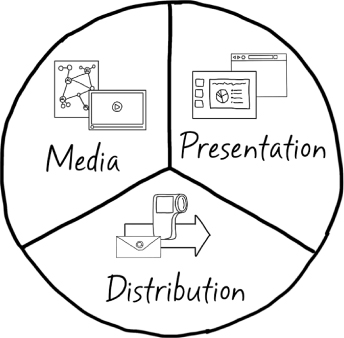

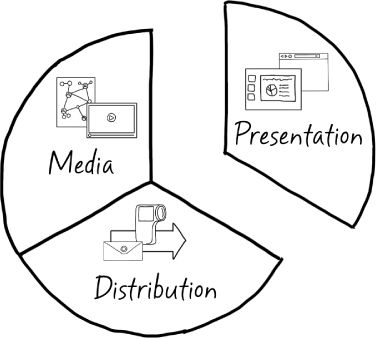

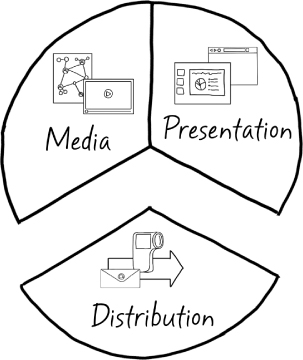

To help us think through these options, let's group them into three big buckets.

As you can see in the following chart, these three options work together and can be used as a process.

In the following I've provided a succinct look at the popular media that can be useful in presenting explanations, as well as the pros and cons of each. For now, our focus is the form of the communication. What form of media or combination thereof can we use to explain?

From McCombs, 2012.

It is likely that your explanation will exist as a combination of the media above. Now that we've covered the basics of each type, it's time to look at our presentation mode options. The question now becomes—where will we put those media? In what container or platform will the media reside?

So far, we've discussed two of the three big considerations: media and mode. This accounts for the variety of media that we can use to display or represent our explanations (media) along with their presentation to the audience (mode). This gives us a solid foundation for thinking about the potential. For example,

The examples are endless. Before getting into how we make these decisions, let's discuss the third consideration: recording and distribution.

To frame this idea, consider an explanation presented orally in a face-to-face meeting. Once the presentation ends, the explanation disappears, only living on in the attendees' minds. Although this may be great in some situations, it limits the potential of the explanation to reach and impact more people. Thanks to new technologies, we now have better options for capturing or recording explanations that we can then distribute and share, increasing the potential audience and making them more useful and powerful. Recording an explanation gives it the chance to spread and flourish into the future.

The explanation from our previous example could be recorded with a basic video camera on a tripod. This would capture it in a form in which others could share and view it in the future. It's this simple idea that turns a meeting, webinar, slideshow, and so on into a video that can reach many more people.

Another example involves slideshow software such as PowerPoint or Keynote. Although you could record a live presentation with a camera, you could also create the same presentation using the voice-over and animation options that come standard with most presentation software. Again, this approach would create an experience that can be easily captured and spread. As you consider how to present your explanations, don't forget the potential to record it so it can be more widely shared.

Before getting into the short stories that bring these ideas together, let's review.

It's a lot to absorb and I realize that it may seem overwhelming. However, as you'll see in the following, we have ways to distill all this information and apply it to the realities of our professional lives.

As constraints have shown us previously, abundance can be paralyzing. Therefore, we need ways to understand the options before us and determine which ones make the most sense for our situation.

Instead of defining the perfect tool for every situation, I think it's more powerful to think at a higher level about the basic options we have and learn to use constraints to help us decide what will work best. Two types of constraints that we'll use are:

For a simple and rather extreme case, let's meet Ivan.

Although these constraints might initially seem limiting, they actually provide a service to him because he can quickly hone in on the best options by considering the constraints on his audience and media options.

For most readers, this decision likely will be more complex because Internet communication is usually a viable option. Here are a few examples of people who chose to present their explanations by considering media, presentation, and distribution in the context of their personal media and audience constraints.

Jackie has been selling software for a decade, and now that she's taken another look at the potential of explanation, she's ready to try something new. A few weeks ago she wrote an explanation telling the story of a person using her software. She knows that the explanation works, but she also knows that text isn't the best option.

To start, she considers what likely will make the most sense for her audience—busy executives who move from meeting to meeting and are tired of long, boring presentations. They don't read anything longer than a few sentences; rather, they need a quick and remarkable way to see how her software will change the world.

This tells Jackie that her text explanation probably won't work well, and audio shouldn't be considered. They won't take the time to attend a webinar. But a short video, a graphic, a live demonstration, or an interactive website are all potential options.

Jackie also thinks about the media to which she has access. She can knock out bullet-point PowerPoint presentations all day long, but they may not make an impact. Her company has a media team, but they don't have the bandwidth or tools to make a video. The web team is already behind on their assignments and probably can't build something for her quickly. However, they do have graphic designers available.

These constraints bring more focus. Video is out. An interactive website isn't likely. This leaves two options that will fit within the constraints of audience and media:

In the end, Jackie is able to work with a graphic designer to create an infographic that transforms the story in her explanation into a visual that captures the big points in an easy-to-consume and remarkable format. It quickly becomes her go-to resource for grabbing the attention of the busy executives she targets. Now that she has proven it works, she distributes it to her whole team, who make it a part of every pitch.

Akira's technology startup company is going to be a big deal someday, but he's currently having a difficult time explaining it to investors and customers. His team has poured everything into development and now he needs a way to get people to care about it. He wrote an explanation that builds context, tells a quick story, and connects his product to ideas his audience already understands to help with this. But he knows his customers don't read much anymore, so he needs a way to make his explanation remarkable.

When he thinks about his audience, he thinks about money. His explanation needs to help him get funding from investors and eventually, revenue from customers. Soon he sees they all have something in common: they are all tech-savvy and spend a lot of time online. They're overwhelmed by all the new ideas and products on the market. They're looking for something remarkable and, above all, easy to understand.

In terms of media, Akira has many options. Although the company is self-funded right now, the team is gadget-oriented, informed about media, and has some very creative members. His media constraints aren't about access so much as effectiveness. Akira knows that investors will expect a slide presentation, and although he plans to create one later, right now he just needs something to get his foot in the door, and that's a tall order. Text, audio, and live demonstrations are all off the table, and a webinar wouldn't make sense. He sees video and graphics as potential media options, along with an interactive website. Akira works with his team to create a strategy for turning his explanation into something that will be useful and remarkable.

A team member has been experimenting with animated video and has the required tools. These videos are all digital—what is known as motion graphics. The team decides that Akira could present his written explanation in the form of an animated video. It would be around two minutes long and would combine voice-overs and visuals to tell the story.

After a few weeks the video is complete and looks amazing. Suddenly, it's possible for anyone to see the big idea with a small investment of time. The team then recognizes all kinds of sharing opportunities. They upload it to YouTube, put it on the front page of their website and send links to friends and investors with the promise that it will make their product easier to understand.

Although their video explanation wasn't a viral hit, it did turn people onto their company, and even compelled a few investors to pitch in. That was just the beginning, however. The video became an essential part of every presentation because it was something they could show at the beginning to set the stage. They also used it on the website to invite people to test the product. A call-to-action appeared at the end of the video, inviting viewers to take the next step. Plus, because it was shared on YouTube, anyone could embed it on their website and distribute the message to even more people.

Monica has spent most of her life in front of an audience of learners, first as a teacher and then as a corporate trainer. Now that she's working at a large company, she spends a lot of time on the road training users of her company's product. She's always been a firm believer in the power of standup training, in which everyone is in the same room. Being able to ask questions and share a common view of the product is a huge benefit from her perspective.

Monica was therefore very excited when her manager asked her to lead the training on a new product. She loves the process of instructional design and recently has been working to include explanations as part of her training. But her manager explained that things have changed. Travel expenses are too high and she will not be able to train users face-to-face. Now it's up to her to figure out how to make it work.

It's clear to Monica that the audience has specific needs. They must learn about the new product in a situation similar to a meeting, and they must be able to ask questions and see how Monica uses the product. Her users all work in medium to large companies and always have a computer and Internet connection. Furthermore, they have never had problems making time for training, and most have a good understanding of the big idea behind the product already.

Normally, she wouldn't have to think much about media. Most of her presentations simply display the product on the screen as she steps through the process of using it. But she now has to consider what's workable for this situation. She could e-mail an instruction manual with text and visuals to them, but that wouldn't be remarkable. She needs a medium like a live demonstration—something that happens in real time. This will allow her to present her product explanation and have discussions that account for any questions.

It soon becomes clear that a webinar is Monica's best option. She can do almost exactly what she did in-person using the Internet instead. Users would call into a conference line and join an online meeting to see a shared screen. Although this made her a bit anxious at first, she learned to love how effective webinars made her presentations. They reduced her need for travel, thereby allowing her to spend more time with her family.

After using webinar software for a few weeks, Monica noticed a feature she had never used that allowed her to record a webinar. It captured the screen and all the discussion. After trying it, a whole new world opened up. Now she could capture the training sessions and make them available on the company website. This way, anyone who needed a refresher could just watch the recording of their session.

Monica continued to have live meetings, but the ability to capture and distribute them easily meant that she could always point former students to recordings and use her limited time more effectively.

As you can see from these and other examples, your explanation's success is not based on a single factor. A great written explanation can only go so far. To be truly effective, you'll need to consider how to transform your explanation into forms that fit with your audience and their needs. Thankfully, we have more choices than ever before in how we accomplish this. Although the variety of media at our disposal can seem overwhelming, it's not insurmountable. You can't use a simple formula to find the right combination of media for every situation; however, we can use constraints to help give our explanation a form. By thinking in terms of audience and media constraints, we can narrow the choices to a manageable few that fit our needs.

Next, we'll dive into a chapter that focuses on the use of visuals in our explanations and see how visual thinking can be used to represent ideas and solve problems.