Economics can be defined as the system that produces and distributes the goods and services we need. We have never, in human history, had so many economists as we have now, we have never subjected economics to so much research and study, and yet we can’t get it right. Many of these people are probably concerned, decent human beings, but the ethos of our practised economics is suffused with greed. Instead of relating to the words ‘distribution of goods’ economics today has to do with ‘concentration of wealth’. Let’s look at some statistics.

According to The Guardian Weekly, in 2013 the world had 1,426 US$ billionaires, a rise of 210 since 2012. The total assets of these 1,426 people were US$5.4 trillion, up from US$4.6 trillion the year before. The richest person was Carlos Slim, worth US$73 billion, followed by Bill Gates with US$67 billion.

In the 1970s the average American chief executive made about 42 times as much as the average worker. Today that figure has climbed to 380 times as much! (Guardian Weekly, November 2012.)

According to Oxfam in January 2014 the richest 85 individuals owned the same as the poorest half of all the planet’s people, 3 billion of them. Forbes magazine updated this a few months later to 69 of the richest individuals owning the same as the poorest half. In the USA the richest 10% have captured over 90 % of the economic growth since the recession.

During the last few hundred years we have developed a view of the world which sees the progress of civilisation as a linear progression from a savage and brutish Stone Age existence to an ever more civilised future. This is not a paradigm that is common to all humanity. Many cultures have looked back to a golden age in the past, and see history either in terms of waves, with golden ages coming and going, or as a gradual descent into chaos and evil.

In the late 1960s and early 1970s Marshal Sahlins, professor of anthropology at the University of Chicago, researched economics in societies that practised a Stone Age technology, hunting and gathering, largely nomadic, and with a very low material culture. He researched in both archaeology and in contemporary cultures that were similar. His book, Stone Age Economics, revealed a picture diametrically opposed to our prevailing paradigm. People in Stone Age cultures worked from two to five hours a day to satisfy their material needs of shelter, clothing, food and tools. They generally slept for a while during the day. They knew their environment and generally did not store food over long periods, trusting that nature would supply them with what they needed out of its own abundance. Of course there were conflicts, occasional natural disasters, droughts and floods that would lead to starvation and catastrophes, but these were generally occasional, isolated events. Comparing that world to the world of the 1960s, Sahlins estimated that 30–50% of modern humanity went to bed hungry every evening, and remarked that in our time, with all our technical, social and economic progress, we have made starvation an institution: ‘… hunger increases relatively and absolutely with the evolution of culture.’

Economics is a social science that started with Adam Smith (1732–1790) who studied the connection between buyers and sellers, and discovered what is known as the ‘invisible hand of the market place’. Since his time economics has become an established study, and we can define three main developments.

Basic economic activity. A street trader in India.

Classical economics is the foundation of economic thinking, describing how the prices of goods are defined by the relationship between supply and demand. However, this type of early economic thinking did not create tools that national governments needed to intervene and reduce the impact of the busts and booms that nations and regions were experiencing. Neither did it address the fact that the real economy does not function like a machine. Players make decisions and react to the market in a variety of ways that are difficult to predict, and cumulatively produce results that often come as a surprise. Sometimes economics ends up in financial crises. It sees labour, raw materials and energy as just ‘raw materials’ and not living entities with rights and qualities of their own. For example, the scarcity of a raw material is not only a cost factor, but will affect future generations negatively. If we use up all the oil in the world, our grandchildren won’t have any. Similarly, labour is not just a cost analysis commodity, but real human beings with needs and desires. In a similar way little account was taken of pollution and its long term effects by these early economists.

John Maynard Keynes (1883–1946) developed a number of tools, embedded in solid economic theory, which national governments could use to ameliorate the negative effects of busts and booms. These were based on controlling national interest rates and using public spending to get through hard times. Keynesian economics built up the western world after the destruction of the Second World War, and was the basic foundation that created the affluence of Western Europe and North America up to the 1970s.

Monetarism replaced Keynesian economics in the 1970s. The US dollar was taken off the Gold Standard in 1971, and the planet was gradually encircled with trade agreements between rich nations, the World Bank, and other global institutions. Monetarism is associated with a right-wing type of thinking that considers survival of the fittest as best suited to the economic side of life. It has a tendency to favour the rich over the poor, and this can be seen in many countries today as the wealthy become relatively fewer and fewer while becoming richer and richer, while the rest of the population become relatively poorer.

In monetarist economics there is no real consideration of morals or values. It has its own ethics, but these are hidden behind a screen of arguments that ‘this is what the real world is like’.

The system that has produced these results is also referred to as neoliberalism, a deliberate attempt by rich people to introduce structures that make them richer at the expense of everyone else. By clever manipulation, they have managed to deceive the majority of us that hard work and frugal living is all that is needed to give everyone the opportunity to become rich and wealthy. They have managed to convince many sensible people, especially in the USA, that cooperation is a kind of Soviet style communism that, if allowed, would turn the country into a Russian satellite state. Potent myths have been spun, and despite statistical evidence to the contrary, have become accepted as the truth. So we now believe that the Greeks and Spanish brought their economic downfall upon themselves by sitting in the shade and drinking wine. However, in The Guardian Weekly, February 2013, it was reported that in 2011 the average Greek worked 2,032 hours, while the average German worked only 1,413 hours, and in the Netherlands the average Dutchman worked just 1,379 hours.

Greece and Spain experienced disastrous economic collapse in 2008, and the solution that standard economics is offering them is large-scale unemployment. In the real world, when disasters happen, people clearly need to be busy clearing up the damage and rebuilding what has been destroyed. In the economic system we have today, we are told that we will become wealthy again if we make large numbers of people, especially younger people between twenty and forty, unemployed.

Insanity can be defined as having lost contact with the real world. According to this definition, monetarist and neoliberal economists are insane.

Economics and accounting can be used to measure performance. I often say to Permaculture students that if we can’t pay the bills, it isn’t Permaculture. Looking through last year’s accounts should give a picture of how an enterprise fared during the year, information that can be used to plan future activities. But it will only work if the picture is a true one that takes all the factors into account. One of the problems with many corporate accounts today are that some expenses are externalised, which means they are passed on to others outside the enterprise. The best example must be nuclear energy, which is often advocated by its supporters as cheap. In fact, the costs of decommissioning power stations and dealing with the nuclear waste are not factored into the cost of the electricity, but paid for out of taxes. Factoring these costs into the price of nuclear electricity would make it ridiculously expensive. We actually have no idea how much it would cost to keep some of the nuclear wastes safe for tens of thousands of years. Had these subsidies been diverted to research and development of renewables, we would be experiencing an enormous surge of new, cheap and more efficient sources of energy.

Similarly, the cost of destroying natural resources is rarely taken into the account sheet. What is the value of a rainforest compared to the electricity generated by a large dam? It’s only recently that this has started to be explored. Pavan Sukhdev, former Head of Global Markets in India for Deutsche Bank, led a UN study, ‘The Economics of Ecosystems and Biodiversity (TEEB)’, in 2010. They concluded that the value of ecosystem services lost to the world’s economy just from deforestation was somewhere between US$1.4 and US4.5 trillion every year.

A study by Trucost in 2012 concluded that the natural capital impact of the world’s largest companies amounted to about US$7.3 trillion per year. If this were included in their annual accounts, most of these companies would be bankrupt.

A number of initiatives were reported in Resurgence and Ecologist magazine in the autumn of 2013. These approaches are now studying how to incorporate nature into the balance sheet:

• The World Bank’s WAVES (Wealth Accounting and Valuation of Ecosystem Services)

• The Economics of Ecosystems

• Biodiversity for Business Coalition

• Natural Capital Declaration

• Natural or Ecological Economics are now being taught at some universities.

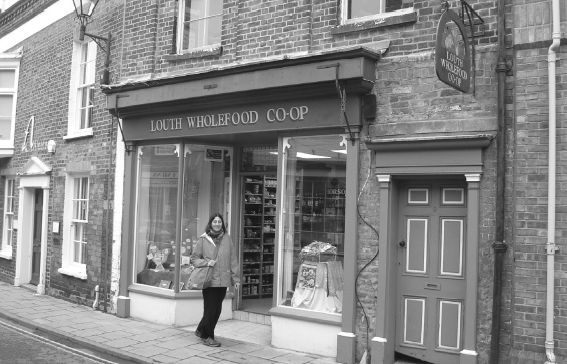

A cooperative keeps capital and wealth in the local economy.

One measure of economic welfare used to be based on counting up the total value of goods and services produced in a country. This would then give you the Gross National Product (GNP). When the government can get the GNP to go up this is seen as a positive development.

However, it doesn’t really tell you how well people are doing. If a company is busy producing something and paying lots of wages to their employees, it will register as a plus in the GNP. If one of the results of their activities is lots of pollution, that doesn’t show. But as soon as health personnel get employed trying to cure those who get ill from the pollution, and government-financed clean-up operations get underway, that also counts as a rise in GNP, as everyone gets paid. Economists who use this can be accused of not discovering subtraction. Simon Kuznets, who invented this way of measuring economic activity, never intended it to be an overall indicator of human wellbeing. However, it has become the indicator that most nations now use, and is unquestioningly accepted as our way of measuring economic performance. As long as the GNP is going up, all is well.

A reaction to this arose in the 1960s and 70s with the development of a whole new range of economic indicators, such as: the ‘Measure of Economic Welfare’ (MEW) by James Tobin and William Nordhaus, or Japan’s ‘Net National Welfare’ (NNW). The Society for International Development created the ‘Physical Quality of Life Indicator’ (PQLI), and the United Nations Environment Program developed the ‘Basic Human Needs indicator’ (BHN). What these had in common is a focus on wider phenomena than just money transactions. They didn’t just see everything as an asset, but deducted unwanted or negative effects such as pollution, crime and war.

When we plot these over time we see that both standard GNP and these new economic indicators continued to rise in a similar way until the 1970s. Since then the alternative indicators have tended to fall, while the GNP has continued rising. The 1970s were a kind of watershed. From the austerity of the years during and following the Second World War, different forms of social democracy had led to a rising standard of living for many people in the West. By the 1980s right wing governments in Britain and the United States had relaxed financial controls, freed major currencies from the Gold Standard, and the stage was set for multinational corporations to grow, and for a ‘revolving door’ relationship between them and governments. Monetarism or neoliberalism had set in.

Another way of measuring progress is reported from Bhutan, where the government has developed the ‘Gross National Happiness’ to measure prosperity. The UN has set up a panel to consider ways of replicating this idea in other countries.

It has become clear to many that while mainstream banking and finance practices state that they are value-free, they actually have values such as greed built into them. As a response to this, there has been a vigorous growth of ethical and sustainable banks. In New View magazine, winter 2012/2013, it was reported that these banks now show higher growth rates than conventional banks. They engage with the real economy by financing social and environmental projects rather than financial speculation, and they take a prudent approach by relating lending to their capital assets. Research comparing 22 ethical banks with 28 conventional banks, conducted over a ten year period between 2002 and 2011 showed this very clearly.

In the autumn of 2008, at the height of the finance crisis, I shared an office at Cultura Bank, the ethical bank in Norway inspired by anthroposophy. Lars Hektoen, the bank’s manager, told me over coffee that not only was Cultura Bank unaffected by the crisis, it was actually gaining new customers faster than ever. Because the bank only invested in sustainable projects with solid backing, and because the bank did not speculate, it was truly a sustainable bank. It had become clear to many that it was safer to put their money into Cultura rather than conventional banks.

Domestic vegetable garden ready for spring planting. Natural capital.

In our western tradition we have very different ideas about economics rooted in the Bible. In Leviticus 25, God reveals a system of economics that places the individual and the family as the focus, rather than some abstract notion of ‘free market forces’. This ancient Jewish tradition is concerned first and foremost with how the economy impacts on the welfare of individuals, not with how individuals impact on the welfare of the economy. Seen by God we are passers-by, visitors or strangers in the flow of time.

The land must not be sold beyond reclaim, for the land is Mine. You are but strangers and residents with Me. If your kinsman is in straits and has to sell part of his holding, his nearest redeemer shall come and redeem what his kinsman has sold. (Lev. 25, 23–25)

The cycles of Shmita (every seventh year) and Joval (every fiftieth year, the origin of the word Jubilee) are calculated to both preserve the economic quality of competition, which results in gaps between rich and poor, while balancing the excesses of that quality by creating new opportunities for people to break out of the cycle of poverty. Thus, loans were remitted, slaves and indentured workers redeemed and land was returned to its original owner.

The land is a gift from God, and this gift is meant to make each of us a ‘giver’ in return. Every person must seek actively to cooperate with others so that the present is shared justly. These rules balance any tendency towards greed, and cultivate a sense of justice and compassion. (See article by Michael Graetz, Jerusalem Report, May 26, 2008.)

In Islam, money has positive connotations; wealth is a reflection of God’s favour. Money is mentioned twenty-five times in The Qur’an as God’s grace and blessing, twelve times as mercy, and twelve times as a good deed. The verb ‘to trade’ is used positively throughout The Qur’an. The fact that the Prophet himself, the first Caliphs, great Muslim theologians and authors were well-to-do merchants conferred positive value on trade.

Wealth and family pleasures are God’s grace to mankind but they disguise God’s test of true faith. To turn to God when one is needy, lonely, or sick is not a sufficient sign of true faith. Rather would one still remember God once one is wealthy, healthy, and surrounded by loved ones? To have money is a lure behind which lurks the ultimate test of true faith: would the joys and goods of the earth distract a person from remembering God? (Adapted from an email from Dr Ali Qleibo, lecturer on ancient classical civilisations at al-Quds University, Jerusalem.)

In October 2009 The Guardian Weekly reported that Islamic finance was one of the fastest growing sectors of the global banking industry, expanding between 15% and 20% per year. Islamic finance emerged strongly during the 1970s and is based on Sharia law, prohibiting investment involving interest, gambling and pornography. Both investor and those receiving investment must share the risks, and investments have to be backed by tangible assets. One professor of economics, Stefan Szymanski, commented that Islamic finance has much in common with ethical investment.

I have found it useful to think of money having three distinct and progressive qualities:

• Consumption money can cover daily use. Here there is a dynamic between thrift and profligacy.

• Thrift will create a surplus that will become savings. Here we think in a longer time scale than we do when we consume, when we are really concerned with gratifying needs such as hunger, thirst and shelter. Maybe we can invest in long-term projects. A loan might be necessary to develop a concrete idea. The loan must be paid back when the enterprise gets going, when it enters the consumption economy.

• If we have even more surplus money maybe we can create gift money. Banks and foundations can manage these sums. How far are we willing to give this money full freedom? Can we give it away as a grant? A new idea might need gift money to be developed. This we call risk capital. Completely free money is necessary for development, both for human beings and for enterprises.

The idea of ‘threefolding’ was presented by Rudolf Steiner as part of his lectures on anthroposophy during the last part of the First World War and the years that followed. He based his thoughts on his study of the development of European society over the preceding centuries. In England, he saw the industrial revolution as the modernisation of economic life, leading to demands for fraternity, the development of trade unionism and labour party politics. In France under the French Revolution he saw a change in the legal life leading to demands for equality, and in Middle Europe (later unified to become Germany) changes in the spiritual life leading to demands for liberty. I like to think of this threefolding as the social application of anthroposophy.

Steiner traced how these three great ideals, of Fraternity, Equality and Liberty had been corrupted by the rise of nationalism and the development of the centralised nation state. The three-folded analysis was presented by Steiner as a way of rebuilding Europe after the disaster of the First World War, but his ideas did not gain credence, and the ideas were largely dormant until taken up by other anthroposophists.

In a lecture I attended a few years ago by the leading Israeli anthroposophist, Yishiyahu Ben Aharon, I first heard of threefolding being applied to peacework. Just as a healthy society needs a clear balance between equality in politics, fellowship in economics and freedom in culture, so does a successful peace process need to include dialogue and cooperation in all three aspects. Yishiyahu showed me how the Oslo peace process of the 1990s didn’t succeed because it was only a political process, and not enough progress was made on economic and cultural co-existence.

I found an example of economics being used as a way of bringing conflicting people together in the Jerusalem Report, August 2011, where Shlomo Maital reports from a project at Babson College in Boston, USA. A programme called ‘Bridging the Cultural Gap through Entrepreneurship’ consists of bringing groups of Israeli and Palestinian students together to study business for several weeks, then returning to the Middle East to launch cooperative business ventures.

LETS stands for Local Exchange Trading System, or Local Energy Transfer System. Sometimes known as Green Dollar Systems, they are generally attributed to a scheme started by Michael Linton in Canada in 1983.

There are a wide variety of social purposes with such systems: from resolving local unemployment to elderly care, from mentoring kids to dealing with environmental problems. What they all have in common is to be able to operate in parallel with the conventional money system, and in being able to match otherwise unmet needs with unused resources. How can we encourage this type of economic development? Here are some questions that can serve as starting points:

• What types of products and services can be supplied?

• What is the optimum size for a pioneer enterprise?

• Do we need new business regulations?

• Do we need pioneer business zones?

• Can we organise a Pioneer Enterprise Festival to stimulate ideas and innovations?

• A Pioneer Enterprise Council might link local government, entrepreneurs, and local business people.

According to Rob Hopkins, writing in Permaculture magazine 77, autumn 2013, Transition Town initiatives have developed complementary currencies in several places. In Brixton they launched a ‘Pay By Text’ system and they allow businesses to pay their business rates in the local currency and Council staff can also have their salaries paid in the currency. In Bristol, George Ferguson became the first Mayor to have his salary paid in Bristol Pounds in November 2012.

‘Ecos’ in use at Findhorn.

Another example of a local economy was developed in Rosenheim in Southern Germany by Christian Gelleri, a teacher at a local school. They called it the ‘Chiemgauer’ and after eight years it turned into one of the world’s most successful alternative currencies, according to a report in The Guardian in October 2011. About 2,500 people use it regularly, it is accepted by over six hundred local businesses and has earned over €100,000 for local non-profit organisations.

Not surprisingly, in Spain, where the economy has more or less run out of Euros, local, alternative currencies have been booming. In September 2012 The Guardian reported over 325 local currencies involving tens of thousands of Spaniards. According to the article, similar projects have been developing in Greece, Portugal and other economically-troubled European countries.

In the Dauphin district in Canada there was a pilot scheme from 1974 to 1978 guaranteeing a minimum income (Mincome) for every resident. After it was over, documentation was stored in 1,800 cardboard boxes that were opened only in 2009 by a medical doctor, Evelyn Forget. Surprisingly, she found an 8.5% reduction in hospitalisation over the whole population, including those who did not receive the Mincome. Also documented were fewer work-related accidents, less violence, fewer traffic accidents and fewer psychiatric disorders.

Similar projects have been launched in Namibia, in the village of Otjivero, and in India in the Madyar Pradesh district. They show similar results, a general improvement in the quality of life, in initiatives, and a decline in social problems.

When I was growing up the word ‘capitalism’ had all sorts of negative connotations amongst the radical teenage circles that I was in. I like to think we have moved on since then, and have a more nuanced view of money and capital. Ethan Roland’s clear analysis, based squarely on the Permaculture principles of different kinds of assets, has been very helpful in balancing monetary and other kinds of capital and currency. I have been pleasantly surprised how well this idea has been received in the Permaculture Design Courses that I teach. The following is based on an article in ‘Eight Forms of Capital’ by Ethan C. Roland of Appleseed Permaculture, USA (Permaculture magazine 68, summer 2011.)

Ethan’s starting point is a definition of capital as ‘wealth in the form of money or other assets’, which opens up a whole new spectrum of ideas under ‘other assets’. He sketches out the following:

• Financial capital has as its currency money, leading to financial assets and securities.

• Social capital has as its currency connections, leading to relationships and influence.

• Material capital has as its currency materials and natural resources, leading to tools, buildings and infrastructure.

• Living capital has as its currency carbon, nitrogen and water, leading to soil, living organisms and ecosystems.

• Intellectual capital has as its currency ideas and knowledge, leading to words, images and ‘intellectual property’.

• Experiential capital has as its currency action, leading to embodied experience and wisdom.

• Cultural capital has as its currency song, story and ritual, leading to community.

• Spiritual capital has as its currency prayer, intention and faith, leading to spiritual attainment.

Using these ideas as starting points, we can explore the relationships between paid work, volunteer work and activities that are done for pleasure, combining productive end results with positive social experiences. At the end of the article Ethan warns us that there might be a danger that we commodify ecosystem services, spirituality and culture, and that ‘Time and Labour’ are not clearly factored in. As with so many things in Permaculture, the analysis is a starting point for future exploration rather than a given set of ‘truths’. In an Ecovillage setting these eight forms of capital could be the basis of a study-group working to further develop indicators to show how the Ecovillage is developing.

The amphitheatre at Damanhur, filled with the International Communal Studies Association 2007 conference.

Damanhur is a Federation of Spiritual Communities located in northern Italy between Turin and Aosta, an area named Valchiusella. Damanhur was founded in 1975 under the inspiration of Oberto Airaudi (1950–2013), known as Falco (Hawk), and now comprises about six hundred residents.

Every year thousands of people visit Damanhur to try out the social model, study the philosophy and to meditate in the Temples of Humankind, that great underground construction excavated by hand by the citizens of Damanhur and which many have called the ‘Eighth Wonder of the World’. The Temple Halls are an underground work of art, a subterranean cathedral created entirely by hand and dedicated to the divine nature of humanity. It is a great three-dimensional book that recounts the history of humankind through all the art forms, a path of re-awakening to the Divine inside and outside of ourselves.

Supermarket at Damanhur selling vitalised ‘selfic’ food.

The Damanhurian complementary monetary system has been created to give back to money its original meaning: to be a means to facilitate change based upon an agreement between the parties. For this reason it is called Credito, to remind us that money is only a tool through which one gives trust. Thanks to this monetary system, the Damanhurians want to raise the quality of money, by not considering it an end in itself but as a functional tool for exchange between people who share values.

The use of the Credito allows people to see themselves as part of the cultural, social, economic and ethical values linked to the sustainability of the planet. It encourages respect for human beings and for all living creatures.

A wide network of local producers and consumers, including a hundred businesses and over two thousand people, have chosen to use the Credito through a system of agreements. In this way, the Credito encourages an economic and social revitalisation of Valchiusella because it facilitates keeping capital inside the area so that it can be re-invested for the benefit of the local economy.

Linked to the project of the Credito and as a complement to it, there is DES, a system of social loans that accepts deposits and issues financing. DES arose from the idea of a finance service to start up development projects with ethical and social aims. It is possible to participate in these projects by opening a savings account, available to members, with advantageous rates of interest.

In purely technical terms, the Credito is a unit of a working account, used within a predetermined and predefined circulation. Today the Credito has the same value as the Euro.

For more information, see: http://www.damanhur.org

Buying things at Damanhur with the local currency ‘Creditos’ gives a discount.

One of my great tools is the ‘Post It Note’. Just coloured pieces of paper with a strip of glue on one side. You can paste them up on walls or windows or any surface. They come in varying sizes and colours.

This exercise entails asking each participant to think of two to four things that they can offer others, and two to four things they need. These can be products or services. A gardener can offer boxes of vegetables, a bike mechanic can offer to fix bikes, a masseur can offer a massage, a cook can offer a meal. Things that they need can be written on red notes, and things they offer on green ones. Ask them to keep it simple and realistic. Remember to ask them to put their names, and if it’s a new group, their telephone numbers on each note.

It’s good to give them ten to fifteen minutes, but no longer; keep it short and simple. Once they have written, ask them to paste their notes up on the wall, keeping red and green separate.

Once everyone has written, it’s time for a break, and you can ask two volunteers to start matching up the notes, red and green. Anyone can watch and help. Once everyone has a cup of whatever, tea or coffee, get the group together and explain that you have now created the basis for a trading system. All they have to do is agree on a common currency, it could be time (ecohours) or an agreed payment of something symbolic (ecobeads). This is the beginning of real economics, and a break to give them time to trade would be appropriate at this point. If the seminar stretches over several days, it would be good to give the group additional time to develop this trading system.

Creating an alternative currency. From a Permaculture Design Course in Norway, 2013.

Ritual and celebration helps to weld a group together.