“WHEREAS IT HAS BEEN REPRESENTED TO US that the science of magnetism may be essentially improved by an extensive series of observations made in high southern latitudes,” the lords commissioners of the Admiralty, the Second Earl of Minto and the Third Baronet of Paglesham, wrote in 1839 to Captain James Clark Ross, “you will proceed direct to the southward, in order to determine the position of the magnetic pole, and even to attain it if possible, which it is hoped will be one of the remarkable and creditable results of the expedition.”1 The commissioners’ orders went on to specify the parameters of Ross’s four-year voyage of Antarctic research, which opened the way and set the standard for Scott. They made no mention of colonial acquisition and said little about geographical discovery. Further, despite beliefs that navigable seas might lie beyond the floating pack ice known to surround both polar regions, the orders spoke only of seeking the South Magnetic Pole, not the geographic one.

Improving the science of magnetism was the essential goal. “In the event of England being involved in hostilities with any other powers during your absence, you are clearly to understand that you are not to commit any hostile act whatsoever,” Ross was ordered, “the expedition under your command being fitted out for the sole purpose of scientific discovery.” If successful, the Admiralty lords assured him, the voyage “will engross the attention of the scientific men of all Europe.” The British Antarctic Expedition of 1839–43 aboard HMS Erebus and Terror became one of the great voyages of discovery in British history—finding the Ross Sea, Victoria Land, and the Great Ice Barrier—but that was never its primary purpose. Terrestrial magnetism had become a fascination of the British and wider European scientific communities. This sent Ross south.

Perhaps coined as a sardonic allusion to the evangelical movements then bestirring England, the term Magnetic Crusade became associated during the 1830s with the orchestrated effort to chart the earth’s magnetic field throughout the world. If it was a crusade, then the British Association for the Advancement of Science, or BAAS, was its church and Antarctica the Holy Land it sought to secure for science. In many ways, the crusade fit well with the scientific goals and imperial resources of early Victorian Britain.

Founded in 1831 as a semiprofessional, semipatrician organization of British cultivators of science, the BAAS embraced the utilitarian, fact-gathering ideal of Baconian research. By 1837, Charles Dickens was satirizing it as “the Mudfog Society for the Advancement of Everything” due to its unfocused and often uncritical attention to virtually any topic in science. To many of the BAAS’s early leaders, terrestrial magnetism appeared to offer an ideal subject for their consideration: at once practical, theoretical, and in need of more observed facts from multiple sources. “The trophies of Newton, won at the end of the seventeenth century, made it impossible for the physical philosophers of the eighteenth not to attempt new victories in the application of mechanical principles to the phenomena of the material world,” the Cambridge polymath William Whewell stated in his 1835 report to the association.2 As Whewell saw it, Newton had used seemingly erratic observed planetary locations to produce a mathematical law of gravity that accounted not only for them but also for the movements of falling and orbiting bodies generally. Whewell, the Anglo-Irish geophysicist Edward Sabine, and other BAAS leaders viewed terrestrial magnetism as being on the cusp of a Newtonian moment.

European navigators had used magnetic compasses since the Middle Ages, and as early as 1600, the British natural philosopher William Gilbert had shown that a compass needle points north because the earth itself is a magnet. Compass needles do not point due north, however, but instead swing horizontally toward (though not always directly at) a North Magnetic Pole. Long-distance navigation by compass required knowing the precise variation (or declination) between the geographic north and the magnetic north. This declination varied by place and over time with no known laws explaining the changes. Further, as it approaches a magnetic pole, a magnetized needle dips (or inclines) vertically toward the pole.

If science could discover a regular law of declination and inclination, the great English astronomer Edmond Halley recognized in the late 1600s, navigators could use it to determine latitude and longitude at sea. Latitude was easily calculated from the sun’s altitude at noon, but a compass method could help in cloudy weather. Determining longitude at sea proved an intractable puzzle until the English horologist John Harrison developed a reliable marine chronometer in the late 1700s, but even then an alternative compass method offered many advantages. The navigational value of knowing longitude and latitude appeared so great that, in 1699, the Admiralty gave Halley, a civilian, command of a navy vessel to measure magnetic variation and dip throughout the Atlantic Ocean to the high southern latitudes. It was the first purely scientific voyage by a British navy ship, and it ultimately reached past 50° south.

Charts of observed magnetic declination and inclination, with their gracefully curved isogonic and isoclinic lines, had limited lasting value because these factors change over time. As some sailors discovered through shipwreck, magnetic lines move—and straying off course by even a few minutes of arc could prove fatal. The earth’s magnetic field also changes in intensity over time and place, which further confused its use in navigation. For over a generation after Halley’s pioneering work, leading researchers virtually abandoned the field as hopelessly complex.

By the early 1800s, some physicists and naturalists had returned to the topic in the hope that, with sufficient data collected over an extended time from across the globe, they could discover regular laws of short-term (or diurnal) and long-term (or secular) change in terrestrial magnetic variation, dip, and intensity. In an era of expanding international trade, knowing these laws could improve the accuracy of navigation, particularly in the increasingly important sea lanes of the high southern latitudes—the so-called Roaring Forties and Furious Fifties—where magnetic readings were highly unreliable. The independent discovery during the early 1800s of relationships between magnetism, electricity, and mechanical motion gave reason to believe that any basic findings about the earth’s magnetic field might also have practical value for communications and industry. Finding the fundamental laws of terrestrial magnetism became the object of the BAAS’s Magnetic Crusade, which inspired Ross’s expedition to Antarctica.

Despite its early prominence in the field, by 1830 Britain had fallen far behind its Continental rivals in magnetic research. Working mostly in Paris from 1804 to 1827, the charismatic German naturalist Alexander von Humboldt developed and popularized his theory that various dynamic cosmic and terrestrial forces continually affect the earth’s magnetic field, causing it to change over time and place. Beginning in the 1820s, based on his theory that terrestrial magnetism emanated from stable features in or on the earth, the renowned German mathematician Carl Friedrich Gauss attempted to deduce regular periodic cycles of long-and short-term magnetic change from historical records. Both Humboldt and Gauss pleaded for more data, leading to the founding of magnetic observatories in France, Germany, and, under the direction of Adolf Kupffer, across the vast Russian Empire. Before 1830, some independent British researchers joined the cause, and taking magnetic readings became an ancillary activity on British Arctic expeditions. The highlight of this early effort came in 1831, when the dashing young navy commander James Clark Ross—widely regarded as the best-looking officer in the fleet—reached the North Magnetic Pole, where he triumphantly recorded a virtual 90° needle dip. This well-publicized episode helped stir popular support for magnetic research in Britain.

At its first annual meeting, held in 1831, the BAAS called for “a series of observations upon the Intensity of Terrestrial Magnetism in various parts of England.” A year later, the association’s second annual report added the lament, “When Baron Humboldt boasted to the French Academy of the wide distribution of his ‘maisons magnetiques,’ or magnetic observatories, from Paris, the center of civilization, to the wilds of Siberia, . . . it is a humiliating fact that he could not with truth have mentioned Britain as possessing a solitary establishment of this description.” In its fifth year, the association voted to ask the government to erect magnetic observatories throughout the empire and to dispatch “an expedition into the Antarctic regions . . . with a view to determine precisely the place of the Southern Magnetic Pole or Poles, and the direction and inclination of the magnetic force in those regions.” The idea of multiple poles derived from a hypothesis advanced by Halley and still favored by Sabine that two magnetic poles, plus a magnetically significant midpoint between them, existed in each hemisphere. They thought that the interplay of these points might explain the variability in the earth’s magnetic field.3

Forewarned that the government was not yet ready to respond favorably, the association did not formally advance its plea for publicly funded magnetic research in 1835. Instead, to boost its case, it secured an endorsement for the proposal from Britain’s senior science organization, the Royal Society, as well as a letter of support from Humboldt and the active involvement of the well-connected astronomer John Herschel.

In 1838, the association renewed its call for a network of government-funded magnetic stations in Britain and its colonies. The observatories would join with European facilities to make coordinated and, on certain “term days,” simultaneous readings of magnetic “horizontal direction, dip, and intensity, or their theoretical equivalents” around the globe over a period of years. The new resolution again urged the navy to send an expedition to explore high southern latitudes, with a focus on the regions southeast of Australia where, according to Gauss, the South Magnetic Pole should lie. “The magnetism of the earth cannot be counted less than one of the most important branches of the physical history of the planet we inhabit,” the gentleman geologist Roderick Impey Murchison noted in his 1838 presidential address to the association, “and we may feel quite assured, that the completion of our knowledge of its distribution on the surface of the earth would be regarded by our contemporaries and by posterity as a fitting enterprise of a maritime people.” Ross, he said, should lead the Antarctic expedition.4

Herschel, already famous for his catalogue of stars in the Southern Hemisphere, stepped forward to offer the resolution on magnetic research at the association’s 1838 annual meeting. Individual researchers could make magnetic observations in many places, he argued, but only a navy expedition could reach the Antarctic. “The seas, which must be the scene of inquiry,” Herschel noted, “are visited by no commercial enterprise, and traversed by no casual vessels belonging to the British or any other navy. Nevertheless, it is vain to hope for a complete magnetic theory till this desideratum be supplied. The unsymmetrical form of the magnetic curves will baffle every attempt to reduce them under general laws, and will remain, as at present, an object of idle wonder, until these points, which may be looked upon as the keys to the enigma they offer, shall have been ascertained.”5

Association annual meetings having become major public events in Britain, Herschel took the opportunity to address the sensitive issues of taxpayer cost and government priorities. Should anyone question spending public funds for “merely theoretical research,” Herschel answered that “it is true [that the voyage] is to perfect a theory, but it is a theory, pregnant, as we see, with practical applications of the utmost importance.” Declaring terrestrial magnetism the branch of science that “at the present moment, stands nearest to the verge of exact theory,” he asserted that “great physical theories, with their trains of practical consequences, are preeminently national objects, whether for glory or for utility.”6

Herschel also chaired the Royal Society committee charged with reviewing the proposal. “The changes in the position assumed by the [compass] needle at any particular point on the Earth’s surface might be conceived as resulting from regular laws of periodicity,” Herschel wrote in his committee’s report. These periodicities could be determined by the coordinated collection of global data on lines of magnetic variation, dip, and intensity, “especially in the antarctic seas.” Concluding “that a correct knowledge of the courses of these lines, especially where they approach their respective poles, is to be regarded as a first and, indeed, indispensable preliminary step to the construction of a rigorous and complete theory of terrestrial magnetism,” the committee recommended, and the Royal Society resolved, that the British government should send a navy expedition to the Antarctic. The British scientific community stood united behind the Magnetic Crusade.7

Herschel turned his attention to lobbying the government. “Dined today with the Queen at Windsor Castle where had much conversation with Lord Melbourne [the prime minister], about the projected South Polar Expedition,” he jotted in his diary for October 15, 1838. Herschel also joined Sabine and Ross in lobbying the Admiralty. Science won the day. On September 30, 1839, Erebus and Terror departed from Britain with equipment for new magnetic observatories at the island of Saint Helena, the Cape of Good Hope, and Tasmania plus instructions to chart terrestrial magnetism in the “antarctic seas” from the Kerguelen Islands in the west to the Falklands in the east and south to the Magnetic Pole.8

Incoming BAAS President W. Vernon Harcourt, an aristocratic Anglican cleric with a passion for science, met with Ross shortly before the expedition set sail. “We sat down, Gentlemen, before his chart of the Southern Sea, and the unapproached pole of the earth,” Harcourt reported at the association’s 1839 annual meeting. “He put his finger upon the spot which theory assigns for the magnetic pole of verticity, corresponding to that which he had himself discovered in the opposite hemisphere. . . . I must confess, Gentlemen, it felt as one of the white and bright moments of life: such a conversation, at such a moment, with [such] a man.” Harcourt called it “the most important and the best-appointed scientific expedition which ever sailed from the ports of England.” Considering the expedition as part of a global Magnetic Crusade, Whewell expressed the feelings of many of its champions when he wrote, “The manner in which the business of magnetic observation has been taken up by the governments of our time makes this by far the greatest scientific undertaking which the world has ever seen.”9

Ross’s Antarctic expedition far exceeded any realistic expectations placed on it, and did so mostly in its first Antarctic summer. After establishing fixed magnetic observatories at Saint Helena, the South African cape, and Tasmania and taking its own regular magnetic readings in the Southern Hemisphere for over a year, the expedition broke through the ice pack south of New Zealand on a compass line for the South Magnetic Pole. No ship had ever penetrated this dense mass of broken sea ice. “After about an hour’s hard thumping,” as Ross described it, on January 5, 1841, the expedition found open sea beyond the pack and continued south. “We now shaped our course directly for the Magnetic Pole,” which at this point meant sailing in a southwesterly direction. “Our hopes and expectations of attaining that interesting point were now raised to the highest pitch, too soon, however, to suffer as severe a disappointment.”10

Six days later, the expedition encountered an unexpected obstacle in its path to the west: a vast expanse of land. “Although this circumstance was viewed at the time with considerable regret, as being likely to defeat one of the more important objects of the expedition, yet it restored to England the honour of the discovery of the southernmost known land,” Ross noted in his report to the Admiralty. “It rose in lofty mountain peaks of from 9,000 to 12,000 feet in height, perfectly covered with eternal snow; the glaciers that descended from near the mountain summits projected many miles into the ocean.”11 Fittingly, Ross named many of the highest peaks for leaders of Britain’s Magnetic Crusade: Sabine, Herschel, Whewell, Murchison, Harcourt, and more.

Blocked by the projecting ice from reaching the mainland, Ross claimed possession of it for Britain by briefly planting the nation’s flag on an offshore islet. “The island on which we landed is composed wholly of igneous rocks, numerous specimens of which, with other imbedded minerals, were procured,” Ross reported to the Admiralty. “Inconceivable myriads of penguins completely and densely covered the whole surface of the island,” he added in his published account, “attacking us vigourously as we waded through their ranks, and pecking at us with their sharp beaks, disputing possession.” In a flourish of unbridled imperial Victorian optimism, Ross named the place Possession Island and speculated that its deep beds of penguin guano “may at some period be valuable to the agriculturalist of our Australasian colonies.” He called the newfound region Victoria Land.12

Thinking the sighted land might be merely a large island blocking his western advance, Ross attempted to reach the magnetic pole by sailing south along its coast. Regularly recording needle dips in excess of 88° at various points—which Ross estimated to put Erebus and Terror within 160 nautical miles of the magnetic pole—the expedition gradually worked its way south of its goal and far beyond the previous Farthest South attained by any vessel. It became apparent that, if Ross’s estimates proved correct, the magnetic pole lay on land and either in or beyond the rugged range of coastal peaks. Much to his frustration, the ships were sailing past the magnetic pole without getting closer to it. By this time, the expedition was somewhere between the magnetic and geographic poles, and the ships’ compasses showed it heading north rather than south.

“Still steering to the southward,” Ross reported to the Admiralty, “a mountain of 12,000 feet above the level of the sea was seen emitting flame and smoke in splendid profusion.” He named this volcano Mount Erebus for his flagship. Ross later commented, “The discovery of an active volcano in so high a southern latitude cannot but be esteemed a circumstance of high geological importance and interest, and contribute to throw some further light on the physical construction of the globe.”13 Erebus would become a prime objective for later researchers, including geologists on Shackleton’s Nimrod expedition. Ross named a nearby dormant volcano Mount Terror for his other ship.

Not long after sighting Mount Erebus, Ross encountered a second obstacle: a massive wall of ice that blocked any further progress south and dashed his hope of finding a southern route around Victoria Land. “This extraordinary barrier presented a perpendicular face of at least 150 feet,” Ross wrote, “completely concealing from our view every thing beyond it, except only the tops of a range of very lofty mountains in the S.S.E. direction.”14 After sailing east along the Great Ice Barrier for more than three hundred nautical miles, the explorers returned to the Victoria Land coast and, with winter bearing down, retreated to Tasmania, where the island’s colonial governor, the former Arctic explorer John Franklin, greeted them warmly. He materially aided the expedition’s efforts to construct the Rossbank magnetic and meteorological observatory in Hobart.

On the return voyage to Tasmania, Ross made a point of investigating the spot where Gauss’s mathematical theory placed the Magnetic South Pole. “Having obtained all the observations that were necessary to prove the inaccuracy of that supposition,” Ross reported, “we devoted some days to the investigation of the lines of no variation” before sailing on to Tasmania.15 Throughout the expedition, Erebus and Terror served as floating observatories that systematically recorded magnetic variation, dip, and intensity in coordination with the international network of fixed stations. The sheer quantity of its magnetic readings was stunning, and their quality was better than anything previously taken at sea.

Although conducting magnetic observations was the expedition’s principal objective and geographical discovery became its greatest legacy, the Royal Society also had sent detailed instructions for research in other fields. Little of the other work had immediate or lasting significance. Indeed, Ross only reprinted that part the instruction manual dealing with terrestrial magnetism in his account of the voyage. Except for Joseph Dalton Hooker, Erebus’s young assistant surgeon who signed on specifically to collect plants, and perhaps Ross, who had mastered magnetism and would became a student of marine invertebrates, none of the ships’ officers and surgeons were trained scientists. Hooker published an important book on plants collected during the expedition that included pioneering observations on marine diatoms. The expedition launched his remarkable career in botany, but otherwise its scientific significance rested on its findings in magnetism and geography.

Erebus and Terror returned south for two more Antarctic summers before heading back to England. These years contributed little to the expedition’s findings. During the second summer, a potentially disastrous collision between the two ships as they sought to elude an iceberg led to a prolonged layover for repairs in the Falklands, where research went on at a relaxed pace. “I never met with such devotees of science,” one Falkland Islander noted. “You would be delighted to see Captain Ross’s little hammock swinging close to his darling [geophysics] pendulum, and a large hole in the thin partition so that he may see it at any moment.” Irony aside, systematic magnetic observations continued. On the ships’ return, the Times of London gushed, “The acquisitions to natural history, geology, geography, but above all towards the elucidation of the great mystery of terrestrial magnetism, raise this voyage to a pre-eminent rank among the greatest achievements of British courage, intelligence, and enterprise.”16

Despite their quantity and quality, the expedition’s magnetic observations did not resolve the basic enigma. Sabine used them and supplementary ones amassed from the southern Indian Ocean by the 1845 voyage of HMS Pagoda and at observatories near Cape Town and Hobart to prepare the first complete map of magnetic lines for the Southern Hemisphere. But the collected data did not guide him to any predictive laws of magnetic change. “All attempts,” he wrote, “that have hitherto been made to connect the secular magnetic change with any other physical phenomena, either terrestrial or cosmical, have signally failed.”17

Five decades after Ross’s voyage, researchers again began agitating for fresh magnetic readings from high southern latitudes, leading directly to Scott’s Discovery expedition. Its scientists would join forces with those from other lands in a second outburst of Antarctica research. For a season, however, interest turned back to the North Polar Regions. In 1845, after Ross declined a commission to take Erebus and Terror to the Canadian Arctic for magnetic research and a possible transit of the Northwest Passage, the Admiralty recalled Franklin for the task. Both ships became icebound on his ill-fated journey, and no one returned. After leading an unsuccessful search effort, Ross retired to study the marine invertebrates collected on his grand Antarctic voyage.

The gracefully curved lines of the isogonic and isoclinic charts so laboriously produced by the Magnetic Crusade during the 1840s gradually became outdated. There was still no theory to predict changes in the earth’s magnetic field. While the surviving network of fixed magnetic observatories supplied sufficient readings to adjust the charts for the middle latitudes, and an ongoing series of Arctic expeditions added enough data for researchers to track changes in the far north, magnetic lines in the far south again became a mystery. No observatories existed to monitor fluctuations in magnetic variation, dip, and intensity for the deep southern sea lanes, despite their steadily increasing use as Britain’s colonies in Australia, New Zealand, and South Africa grew during the late 1800s. Further, with more ships being built of iron and steel, which distort magnetic readings, fewer of them could supply reliable magnetic observations.

Readings taken in the 1870s during the worldwide voyage of the British oceanographic research ship HMS Challenger, which briefly sailed south of the Antarctic Circle below the Indian Ocean, suggested that magnetic lines in the Antarctic region had changed dramatically since Ross’s day. The South Magnetic Pole, which researchers had come to see as an area of land rather than a geographic point, appeared to have migrated northward. Navigators could not rely on old charts. In some areas around Cape Horn, readings suggested that the secular change in declination exceeded ten minutes of arc per year. Challenger naturalist John Murray came back from the voyage calling for renewed magnetic observations from Antarctica, ideally by land-based physicists over an extended period. Soon after, Admiralty Hydrographer Fredrick J. Evans reported to the Royal Geographical Society, “Which ever way we look at the subject of the earth’s magnetism and its secular change, we find marvelous complexity and mystery.” Commenting on Evans’s report in its official journal that “there was therefore a wide field for future research in a primary geographical subject,” the RGS soon emerged as the chief champion of a new British expedition to Antarctica.18

By the 1880s, Britain had a new geopolitical rival. The disparate German states humiliated France in the Franco-Prussian War in 1871 and then unified into a single empire to become Europe’s preeminent Continental power. The Reich then began to build a deep-water navy to challenge British dominance on the high seas, and to assemble colonies in Africa and the South Seas. Germans had long played a leading role in magnetic research, and following the deaths of Gauss and Humboldt, the mantle fell on Georg von Neumayer. Just as Humboldt and Gauss had inspired the founding of an international network of magnetic observatories during the 1820s, in the 1880s Neumayer began advocating a German national expedition to make extended magnetic observations in the Antarctic. Some Britons, threatened by rising German nationalism, wanted to reassert their nation’s claim to the Ross Sea region. “Certainly fifty years is a long time for us to have totally neglected so vast and so important a field,” Clements Markham said in his 1893 inaugural address as RGS president.19 Britannia, which still ruled the southern waves, sought better navigational charts to extend its reign.

Lobbying for a British expedition began in 1885, when retired Admiral Erasmus Ommanney, knighted for his Arctic service during the Franklin searches, lectured the BAAS on the need for new Antarctic research. Citing Neumayer’s work, Ommanney argued that “another magnetic survey is most desirable in order to determine what secular change has been made in the elements of terrestrial magnetism after the interval of forty years.” A naval expedition should winter in the Antarctic much as his ships wintered in the Arctic, he asserted, and investigate all fields of polar science. “No man has ever wintered in the antarctic zone,” Ommanney noted. “The great desideratum now before us requires that an expedition should pass a winter there, in order to compare the conditions and phenomena with our arctic knowledge.” Steamships made it practical, he said.20 Invoking his Challenger credentials, Murray seconded Ommanney’s call, which led the association to name a star-studded Antarctic Committee that included Ommanney, Murray, Hooker, Markham, T. H. Huxley, William Thomson (Lord Kelvin), and two old Arctic hands, Leopold McClintock and George Nares. “If this country spent as much on the exploration of the South Pole as some of our little wars cost,” Murray declared, “they could thoroughly explore the Antarctic region.”21

By this time, Neumayer had orchestrated the formation—without British participation—of the International Polar Commission, or IPC, with representatives from nine continental European nations. Its founding followed the beginning of coordinated international magnetic research in the Subantarctic by German, French, British, and American expeditions during both the 1874 Transit of Venus and, eight years later, the first International Polar Year. Under the IPC’s auspices, during the early 1880s, Germany established a magnetic station on the island of South Georgia, France opened one in Tierra del Fuego, and navy vessels from several nations began systemically collecting magnetic readings in the high southern latitudes. Britain maintained observatories near Cape Town and Melbourne but watched its lead in Antarctic magnetic research diminish.

Despite three years of campaigning by the BAAS and the support of various Admiralty officials and Australian colonies, the tight-fisted ruling Conservative government refused to back a costly new Antarctic expedition. This was decisive because, based on their personal experiences on prior polar voyages, promoters of a renewed effort believed that only the British navy could successfully mount a sustained scientific expedition in Antarctica.

Of all these early promoters, Markham proved the most dogged. He had served as a midshipman in the Franklin searches, where he enjoyed the camaraderie of man-hauled sledging, but subsequently lost interest in navy service though not in naval officers or polar exploration, which he supported throughout his life. Leaving the navy as a young lieutenant in 1851, he worked in colonial administration and participated in public and private expeditions to such diverse places as Peru, India, Ethiopia, and Greenland. By the time he joined the BAAS’s Antarctica Committee in 1885, Markham had served as RGS secretary for over two decades and had established himself as a force within the elite circle that dominated British geographical exploration during the late Victorian era. He was determined that Britain would lead the way in Antarctic discovery, and as Scott later observed, “Sir Clements was favorably placed for carrying out his determination.”22

Although his public pleas for Antarctic exploration followed the party line in stressing the value of South Polar magnetic readings for science, Markham had other interests in mind. Privately, he described the expedition’s main goal as “the encouragement of maritime enterprise” by young naval officers and observed that “the same object would lead to geographical exploration and discovery.” He went on to dismiss the expedition’s stated scientific goals as window-dressing designed to gain support or, as he put it, “springs to catch woodcocks.”23

Even after the BAAS’s initial push for a national expedition faltered, Markham kept an eye out for naval officers to lead it. Among his many activities, he served on a board for training marine officers and often entertained cadets in London. By his own account Markham first spotted Robert Falcon Scott in 1887, when the young midshipman won a hard-fought cutter race in the British West Indies. “He was then 18, and I was much struck by his intelligence, information, and the charm of his manner,” Markham later wrote. At a similar training race five years later, Markham picked out cadet Charles Royds, whom he described as resembling “my beau ideal of a good polar officer,” and in 1894 he met Albert Armitage, a former cadet then serving as navigator on an Arctic expedition. When the Discovery finally sailed, these men were its three principal officers. “He liked boys,” British writer Francis Spufford observed about Markham, “but if he acted on the homosexuality he kept buried beneath a respectable marriage and an array of academic honors, he did so far away from home. Certainly far away from the midshipmen of good family, the bright-eyed merchant marine cadets, whom he began to make his companions in his middle age.”24

Elevation to the RGS presidency in 1893 gave Markham a position to advance his Antarctic agenda. “Articles in magazines had to be published, lectures to be delivered, circulars to be sent out,” he later recalled of his labors in the post on behalf of a south polar expedition.25 Among his first acts as president, Markham invited Murray to address the RGS on the need for Antarctic research, appointed an RGS Antarctic Committee and solicited support for the expedition from the Royal Society, which promptly endorsed its scientific aims but never warmed to Markham’s idea of making the expedition mainly a naval exercise with geographical ends.

Despite his personal preoccupation with geographical discovery, the need for magnetic research featured prominently in Markham’s public pleas for an Antarctic expedition. “The science of terrestrial magnetism is at a standstill for want of recent observations from the far south,” he warned in one of several articles on the topic, “and it is from this point of view that an Antarctic expedition can be shown to be necessary.” Navigators urgently needed this information. “With regard to the probable results of an expedition, the most important would be the benefit to the science of terrestrial magnetism.”26 Commenting on grand aims of coordinated magnetic research, Markham explained that “the object is to achieve a series of synoptic charts which will allow of the variations in the magnetic condition of the whole earth being traced in detail during a definite period, and so to provide the necessary basis from which alone the fundamental problems of terrestrial magnetism can be more clearly approached.”27

As orchestrated by Markham, Murray delivered his 1894 RGS address on the need for Antarctic research to an upper-crust audience of British scientists, explorers, and navy officers, who cheered his remarks. In his speech, Murray set the parameters for what became the Discovery expedition: a three-year, land-based, government-sponsored mission to an unknown continent. Although it might be possible to sledge quickly across the Great Ice Barrier to the pole, he noted, “A dash to the South Pole is not, however, what I now advocate, nor do I believe that it is what British science, at the present time, desires. It demands rather a steady, continuous, laborious, and systematic exploration of the whole southern region with all the appliances of the modern investigator.”28

Although Murray envisioned a complete scientific survey of the region, he also paid homage to the importance of magnetic research. To justify the expedition, for example, he quoted Neumayer: “Without an examination and a survey of the magnetic properties of the Antarctic regions, it is utterly hopeless to strive, with prospects of success, at the advancement of the theory of the Earth’s magnetism.” He added Ross’s lament that, if the 1839–43 expedition had found safe harbor in a Victoria Land bay, the coveted magnetic pole “might easily have been reached by travelling-parties in the following spring.”29 As the enthusiastic response to Murray’s address underscored, the magnetic pole and its properties, not the geographic one, remained the aim of British Antarctic exploration. “It was a great meeting,” Markham crowed, “and Sir John Murray’s address was eloquent and convincing.”30

Markham chaired the London meetings of the 1895 International Geographical Congress as president of the host society. With Neumayer in the hall and terrestrial magnetism front and center, Markham used the occasion to focus international attention on the need for an Antarctic expedition. “It is our duty,” he told the delegates in his opening address, “to show how absolutely necessary some portions of the work of such an expedition have become—for example, the execution of a magnetic survey in the deep south—and to arouse public opinion in favour of an expedition.” Neumayer then made his own case to the assembled delegates. “With fervid words and earnest manner he pleaded the cause of Antarctic research, gaining the sympathy and applause of his entire audience,” one popular magazine reported. Hooker and Murray followed Neumayer to the dais and warmly endorsed his remarks. By a unanimous vote, the congress resolved that “a scientific exploration” of Antarctica was “the greatest piece of geographical exploration still to be undertaken.”31

The congress also heard from Carsten Borchgrevink, an ambitious, scientifically interested Norwegian who had sailed before the mast on a commercial whaling ship to the Antarctic. Earlier in 1895, he erroneously laid claim to being the first person to set foot on the Antarctic mainland when his ship put a small party ashore for less than an hour on Cape Adare at the Ross Sea’s western mouth. “His appearance before the congress was in the nature of surprise, and a hum of appreciative expectation filled the great Institute hall when his presence was announced,” a journalist commented. Knowing of the delegates’ interest in an Antarctic land expedition, Borchgrevink assured them, “I made a thorough investigation of the landing-place because I believe it to be a place where a future scientific expedition might safely stop even during the winter months.” Adding the mistaken claim that from Cape Adare “a gentle slope leads on to the great plateau of the South Victoria continent,” he offered to return with a proper scientific expedition and take a sledge party up the plateau to the South Magnetic Pole.32

Borchgrevink’s offer attracted the attention of British publishing magnate George Newnes, who thought that an Antarctic expedition might make good copy for his mass-market magazines. In return for first publication rights, Newnes underwrote the cost for a modest expedition that left London in 1899 aboard a converted whaler renamed Southern Cross.

Southern Cross deposited Borchgrevink, nine other men, their supplies, sledges, dogs, scientific instruments, and two small prefabricated huts at Cape Adare in February 1899. It retrieved the nine survivors eleven months later. As his magnetic and meteorological observers, Borchgrevink chose British navigator William Colbeck, who had taken a quick course in terrestrial magnetism at Britain’s Kew Observatory, and the young Australian physicist Louis Bernacchi from the Melbourne Observatory, who served a similar role in the Discovery expedition. Despite its exposed location on an isolated peninsula and the death of its able zoologist, Nikolai Hanson, the expedition was the first to winter on land in Antarctica, and it returned with some valuable natural-history specimens and scientific observations. The mountains and water surrounding Cape Adare, however, frustrated every attempt to push into the interior toward the magnetic pole. Further, the expedition lost the distinction of being the first to winter below the Antarctic Circle because a Belgian research vessel carrying Roald Amundsen as first mate had become trapped in the late-summer ice on the other side of Antarctica a year earlier and remained there until the following summer. Both expeditions kept regular magnetic and meteorological records—the first made over an Antarctic winter.

Imperial British science could be fickle. Borchgrevink received more acclaim in 1895 for his unsubstantiated boast of being the first person to step on Antarctica, when that chance occurrence served to show that landing a party there was possible, than he did four years later for actually being the first to winter on the Antarctic mainland, when doing so prevented Scott and his men from claiming that honor. Markham, who had once hailed Borchgrevink as an Antarctic pioneer, later snubbed him in public and cursed him in private for diverting funds and attention from the Discovery expedition. Geography was a cut-throat enterprise in late Victorian Britain. Following his return, Borchgrevink was criticized for allegedly mishandling Hanson’s notes and specimens and for not pushing with sufficient vigor into the interior toward the magnetic pole. Both of these supposed failings of his groundbreaking endeavor conveniently left more for Scott’s all-British team to achieve.

By the time Borchgrevink returned to England in 1900, the British government had finally succumbed to prodigious lobbying by Markham and much of the nation’s scientific establishment and had appropriated public funds for an Antarctic expedition. Even then, the government agreed only to match privately raised funds, most of which came from the British industrialist Llewellyn W. Longstaff, who responded to Markham’s nationalistic pleas for British science with a large enough donation to ensure that the project would proceed. “I only hope that my action may result in important gains to science,” Longstaff wrote to Markham, quoting back Markham’s own motto about the effort. “I felt that ‘It should be done and that England should (help to) do it.’ “33 Crucially for Markham’s vision of the venture, the Admiralty also agreed to release a limited number of junior officers and crewmen for the expedition, which assumed a naval bearing even though Discovery sailed as a private yacht. But Ernest Shackleton, the expedition’s charismatic third lieutenant, came from the merchant marine on Longstaff’s recommendation. Chafing under naval discipline, he would become the only officer to threaten Scott’s authority.

The expedition was costly because its organizers opted to commission a new ship designed for scientific research rather than use a converted Arctic whaler. Adding to the cost, an oversight committee composed of RGS and Royal Society members insisted on a wooden hull in age of iron ships to permit the taking of accurate magnetic readings at sea. “As the Discovery will have to do important magnetic work, a special magnetic observatory will be constructed and fitted on the upper deck,” the Times of London reported. “Special care will be taken that no ironwork shall be used for any purpose within a distance of 30 feet of this observatory. Where metal must be used, it will consist of rolled naval brass.”34 The ship’s auxiliary steam engine was placed as far as possible from the observatory. Discovery was a purpose-built ship and its purpose was magnetic research on open water, in pack ice, and when frozen in place. It cost over twice as much as a whaler, rolled excessively in heavy seas, and leaked badly.

The final nudge for the British government to support Antarctic research came in 1899, when the German Reichstag yielded to Neumayer’s pleas by voting to fund an Antarctic expedition commanded by a scientist-explorer, Erich von Drygalski. It, too, sailed in a purpose-built wooden ship designed for magnetic research, the aptly named Gauss. Ultimately, Britain would not abandon this field to its rising rival. “The Nation’s credit is at stake,” Markham warned even as he urged that the two empires collaborate on a comprehensive Antarctic magnetic survey. “Shall we let strangers do England’s work?” At the time, Britain and Germany were still probing their new relationship as potentially coequal European powers. “It must rejoice the hearts of all geographers,” Markham proclaimed, “that the countrymen of Humboldt . . . should combine with the countrymen . . . of Sabine to achieve a grand scientific work which will redound to the honor of both nations.”35 At the 1899 International Geographical Congress in Berlin, delegates agreed that Britain would focus its efforts on two quadrants of the Antarctic south of Australia and the Pacific Ocean, which included the Ross Sea, while Germany would explore the little-known quadrant under the Indian Ocean. The final quadrant went to Sweden, which sent an expedition that contributed a coordinated set of magnetic observations despite having its ship crushed in the sea ice off the Antarctic Peninsula.

After establishing a base magnetic station far south in the Indian Ocean on the deserted Kerguelen Islands in 1901, the Gauss expedition sailed toward Antarctica. But the ship became locked in sea ice more than fifty miles from the coast, and its scientists spent the winter taking magnetic readings and conducting such other research as their location allowed before the ship broke free and returned north in 1903. Drygalski was forced to abandon his earlier plan of attempting to reach the magnetic pole from the west and made only sporadic trips over the sea ice to the mainland.

During the same period, privately funded expeditions from Scotland and France explored the Antarctic Peninsula and Weddell Sea. Although they also took magnetic readings, these expeditions were not invited to participate in the coordinated magnetic survey built around the voyages of the British, German, and Swedish ships. When the Scottish expedition’s proven leader, William Speirs Bruce, offered his ship’s service for the survey, Markham—already furious with him for diverting private Scottish funds from the official British expedition—refused on the doubtful grounds that Bruce’s vessel was unsuited for magnetic work. “If not specially built for magnetic observations,” he wrote to Bruce, “your ship cannot co-operate with the British or German Expeditions in that way, which is the main point; so that there can be no cooperation on your part. The National Expedition is in serious want of more funds, and your proceedings are exceedingly harmful to it, by diverting all chance of help, so far as you can succeed in doing so, from Scotland.”36 The Scots placed their observatory on the South Orkney Islands, where it still operates.

A deeply divided joint committee of the RGS and Royal Society sent official instructions to the Discovery expedition that gave equal primacy to magnetic research and geographical discovery. “The objects of the expedition are (a) to determine, as far as possible, the nature, condition, and extent of that portion of the south polar lands which is included in the scope of your expedition; and (b) to make a magnetic survey in the southern regions to the south of the 40th parallel.” With the RGS caring most about geography and the Royal Society primarily interested in magnetism, the instructions stressed that “neither of these objects is to be sacrificed to the other.” As Markham later noted, “All mention of the [geographic] south pole as an objective was carefully avoided.” Regarding the magnetic survey, the committee counseled Scott, “The greatest importance is attached to the series of magnetic observations to be taken under your superintendence, and we desire that you will spare no pains to insure their accuracy and continuity.” In particular, the expedition was to take regular magnetic readings both as it sailed in the South Pacific or Ross Sea and on sledge journeys from an Antarctic base station after it landed. Armitage supervised magnetic research at sea; Bernacchi took charge on land.37

The Antarctic magnetic station consisted of two small asbestos-walled huts erected at Ross Island behind the expedition’s main building upon a rocky peninsula that became known as Hut Point. By the shore of McMurdo Sound across from Victoria Land, this site served as the explorers’ winter quarters. Official instructions called for a party to winter in Antarctica, with Scott free either to keep Discovery “in the ice” or to sail it north for the winter.38 He opted to winter his ship at Hut Point. It remained frozen in place for twenty-four months before the sea ice broke out. The expedition’s extended stay at Hut Point permitted the systematic collection of magnetic readings over a two-year period.

During their first year at Hut Point, in addition to making regular observations of variation, dip, and intensity, Discovery’s researchers coordinated with those on Gauss and at other deep-southern stations in taking simultaneous observations of declination, vertical force, and horizontal force every hour on twice-monthly term days and every twenty seconds for one hour on each of those days. Bernacchi, whom Scott privately characterized as “full of grand conceits and foibles but full also of puck and a hard worker,” coordinated and largely conducted the effort. “For the ordinary routine work,” Bernacchi noted, “there were self-recording instruments which required to be visited once or twice a day, but on the 1st and 15th of every month, the international term days, I had to visit the magnetic huts every two hours of the twenty-four, to change the photographic recording sheets.” Because the unheated huts became buried in snow, which helped to keep conditions constant for the instruments, the inside temperature hovered around −30°F. Bernacchi’s work resulted in a three-hundred-page book of magnetic readings published by the Royal Society in 1909 and used by physicists for a generation. “In general,” Scott wrote to a Royal Society official on Discovery’s return to Britain, “I am ready to plead ignorance of the value of our Scientific work but when it comes to magnetic results I make bold to say that our light ought not to be dimmed by anything that other expeditions can produce.”39

Locating the South Magnetic Pole remained a stated objective of the Antarctic survey. Unaware that Drygalski had abandoned his quest for it, the British expedition made its assault on the magnetic pole during its first full Antarctic summer. Already drawn to the idea of reaching the geographic pole, during the first summer Scott headed south across the Ice Barrier, with Shackleton and Discovery physician, artist, and budding zoologist Edward A. Wilson. But knowing the importance Markham placed on claiming the magnetic pole for Britain, on November 29, 1902, Scott dispatched a large team west under Armitage with the unrealistic goal of reaching it. At least, he reasoned, this Western Sledge Party might discover whether an ice sheet or coastline lay beyond the Victoria Land mountains. This in turn might resolve the geographical question, was Antarctica a continent or an archipelago of islands?

Because it remained icebound at Hut Point, far to the south and west of the magnetic pole, Discovery could not ferry Armitage and his men to a point on the same parallel with the pole. Yet the sea ice farther north looked too unstable for sledging. So the party crossed the stable ice near Hut Point and from there ascended a glacier between the mountains in the hope of finding a route north on the far side. “In all twenty-one souls went forth to try to surmount that grim-looking barrier to the west,” Scott observed. In deference to Markham’s armchair conception of this venture, which drew heavily on his nostalgic memories of the Franklin searches, they pulled their sledges without the aid of dogs. “The distance of Ross’s magnetic pole from McMurdo bay and back could very easily be covered in three months,” Markham had told fellow geographers in 1899, “without the cruelty of killing a team of dogs by overwork and starvation.”40

Nothing in the sixty-year history of man-hauling sledges in the Arctic could have prepared Armitage and his men for the ordeal of pulling ten heavy sledges, loaded with two tons of supplies, equipment, and scientific instruments, across the mountains of Victoria Land. Armitage initially hoped to run the sledges on a glacier that cut through the range but, on inspection, that route looked impassably steep and icy. “It would be madness to attempt it,” one officer advised him. Instead the party tried to pick a route between the peaks by relaying loads and using improvised block-and-tackle techniques to get the sledges up steep pitches and over outcroppings. Each false summit simply led to another until the party reached a dead end after gaining some six thousand feet in altitude. “To our intense disappointment, there was no route for sledges,” Armitage wrote. “All our toil had been for nothing.”41

Rather than give up, they went back down to try the glacial route, which proved almost as difficult as it looked. Every man showed signs of scurvy, and some were left behind. One suffered a near-fatal heart attack. Armitage once fell through a snow bridge and hung by his harness until rescued. Blizzards kept the party confined for days; ice falls, crevasses, and moraines blocked the way. “The worst feature of a pioneer journey inland is that, not knowing where the road leads to, it is impossible to proceed in thick weather,” Armitage noted. After thirty-seven days, he finally summited with five men at about nine thousand feet and looked out over the Polar Plateau. “How far the ice-cap extended it was impossible to say,” Armitage added, “we had to rest content with being the first men to have actually found it.” Utterly beat, they turned back without further thought of the magnetic pole. Collecting their colleagues along the way, they reached Hut Point without losing anyone. “It was a piece of excellent pioneer work,” Markham later declared. “The journey,” Scott commented in his first-year’s report to the Royal Society, “reflected great credit on Mr. Armitage.” William Bruce hailed the effort as “almost superhuman.”42

The Western Sledge Party showed a way through the coastal range and suggested what lay beyond. Its magnetic readings helped researchers compute the magnetic pole’s location, which had migrated significantly since Ross’s day. Further, with the expedition extended for a second summer, Scott used Armitage’s route to reach the plateau but then, instead of turning north toward the magnetic pole, pushed west in a vain effort to cross Victoria Land. This left a second grand objective for Shackleton when he returned to Ross Island aboard Nimrod in 1908 with his own privately funded expedition.

Shackleton’s Nimrod expedition was all about Firsts and Farthests. “I never saw anyone enjoy success with such gusto as Shackleton,” RGS Librarian Hugh Robert Mill observed. “His whole life was to him a romantic poem, hardening with stoical endurance in adversity, rising to rhapsody when he found his place in the sun.”43 Although he had his eyes fixed on being first to the geographic pole, or at least getting farther south than he had with Scott in 1902, Shackleton recognized the long-standing scientific interest in reaching the magnetic pole and made that “first” a part of his expedition’s mission. For the so-called Northern Sledge Party, whose journey to the magnetic pole would coincide with his own run south, Shackleton chose the expedition’s fifty-year-old geologist, noted University of Sydney professor T. W. Edgeworth David; David’s former student Douglas Mawson, who taught mineralogy at the University of Adelaide but joined the expedition as its physicist; and the expedition’s Scottish physician A. Forbes Mackay.

Placing David in overall command, Shackleton directed the party “to take magnetic observations at every suitable point with a view of determining the dip and the position of the Magnetic Pole. If time permits, and your equipment and supplies are sufficient, you will try and reach the Magnetic Pole.” Reaching the magnetic pole was a highly ambitious goal for a three-person, two-sledge team pulling up to twelve hundred pounds over an unknown route in subzero temperature. The party would leave the expedition’s winter quarters at Cape Royds, nearly twenty miles north of Scott’s base at Hut Point, early enough in October to sledge over the sea ice to Victoria Land and then proceed north along the frozen coast to Terra Nova Bay. Including relay work, the outbound Ross Sea portion of the trip totaled 260 miles. Then the party would need to climb up to and cross a portion of the seven-thousand-foot-high Polar Plateau—a 520-mile-long round trip. They roughly knew these distances in advance from data gathered by the Discovery expedition. Shackleton also directed the party “to work at the geology of the Western Mountains” and “to prospect for minerals of economic value” in the snow-free “Dry Valley” discovered there by Scott in 1903. Curiously, it was the young physicist Mawson who favored geologizing in the nearby Dry Valley, while the older geologist David seemed hell-bent on reaching the magnetic pole.44

The Northern Sledge Journey was a forced march of foreseeable brutality. Early on, David suggested traveling on half-rations to lighten the load. “I cannot see how it is possible for us to reach the Magnetic Pole in one season under such conditions,” Mawson complained in his journal. Instead, he reported telling the others near the outset, “(1) We must give up all else this summer, (2) preserve about a full ration of sledge food for 480 m journey inland, (3) in order to make this possible we must live on seal flesh and local food . . . as much as possible.” The trip would take over three months, he calculated. With the sea ice gone by the time they returned to the coast, they would have to hope that Nimrod came to retrieve them. Mawson wanted to give up the pole and concentrate on geology, but David refused. “I cannot do anything but agree and I give my whole power toward it,” Mawson asserted in a private journal entry.45

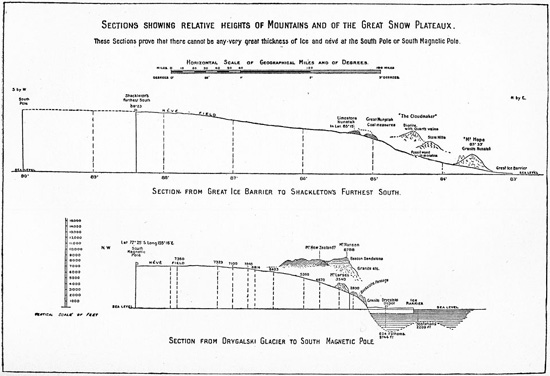

Sketch showing the elevation of mountains and the polar plateau crossed by the Nimrod expedition’s Northern and Southern Sledge Journeys (1908–9), from Ernest Shackleton’s Heart of the Antarctic (Philadelphia, 1909).

Hunger stalked them. “About 18 days out I had a food dream,” Mawson wrote. “Dreamt that we came upon a depot containing all sorts of choice delicacies.” Instead, their overland sledging rations consisted mostly of pemmican and biscuits from which they made hoosh stew. While on the sea ice, they lived mainly on seals and penguins. “Young bull seal is always good—steak from loins, liver and blubber,” Mawson noted. “The tongue we found good but kidney rubbery and useless. Cow seal in breeding season is to be avoided. . . . Have found the penguin liver the best of all yet.” Still, the food was never enough and sometimes made them sick. “When feeding on seal meat,” Mawson reported, “we opened out every hour at least.” They planned future feasts while sledging. “We dote on what sprees we shall have on return—mostly run to sweet foods and farinaceous compounds. We don’t intend to let a meal pass in after life without more fully appreciating it.”46

After two months on the sea ice, the party began ascending a glacial incline toward the plateau. Blizzards became common, and the men regularly fell into crevasses. They set themselves a goal of covering at least ten miles per day, which could mean more than twelve hours of heavy pulling. They got little sleep. “A three-man sleeping-bag, where you are wedged in more or less tightly against your mates, where all snore and shin one another and each feels on waking that he is more sinned against than shinning, is not conducive to real rest,” David commented in his journal. “The Prof is dreadfully slow,” Mawson complained about the middle-aged David on New Year’s Eve. “Food very little now as original supply has undergone two reductions.” Worst of all, Mawson added, “Dip reading very little less than previous and very discouraging.”47 Frostbite, snow blindness, and bleeding lips plagued them; David stumbled often. On January 12, when they had reached the place where they thought Bernacchi’s data placed the pole, they found that it had migrated northwest and they needed to go forty more miles. “This was extremely disquieting news, for all of us as we had come almost to the limit of our provisions,” David wrote. “We decided to go on for another four days.”48

On the fourth day, January 16, 1909, they reached the magnetic pole—or at least the vicinity of where Mawson estimated that the pole’s mean position should lie. “The determination of the exact centre of the magnetic polar area could not be made on the spot, as it would involve a large number of readings taken at positions surrounding the Pole,” he explained. As it was, he barely had time to rig the camera for a group photo. “Meanwhile, Mackay and I fixed up the flagpole,” David wrote. “We then bared our heads and hoisted the Union Jack at 3:30 p.m. with the words uttered by myself, in conformity with Lieutenant Shackleton’s instructions, ‘I hereby take possession of this area now containing the Magnetic Pole for the British Empire.’ At the same time I fired the trigger of the camera.” They gave three cheers for the king and left. “It was an intense satisfaction,” David observed, “to fulfill the wish of Sir James Clarke [sic] Ross that the South Magnetic Pole should be actually reached, as he had already in 1831 reached the North Magnetic Pole.”49

Seventy years after Ross first set sail for it, British polar explorers had finally claimed this Antarctic goal, but scientifically it did not mean much. Magnetic poles hover in an area rather than reside at a point, and members of the exhausted party made no dip readings at the claimed site. They had left their magnetic instruments at the final outbound camp and, on the last day, simply sprinted toward their best guess as to the pole’s position. Their compass’s horizontal element had ceased working several days earlier, and the recorded dip never quite reached 90°.

David, Mawson, and Mackay then faced an agonizing 260-mile dash for the coast in an increasingly desperate attempt to catch Nimrod before it sailed north. They made it to the coast in less than three weeks despite frequent falls due to the steep ice and soft late-summer snow. Apparently brutalized by the effort, Mackay began kicking David to speed his pace and called him “a bloody fool” for falling. By the end, David was so disorientated that he relinquished command to Mawson. “He says himself that had he known the magnitude [of the task] he would not have undertaken it,” Mawson wrote in his journal four days before the Nimrod rescued them.50 Years later, both David and Mawson concluded that they had probably never quite reached the pole.

For the expedition, however, their journey was seen as a towering achievement. Bernacchi hailed it as “most valuable and important.” When Shackleton fell short of reaching the geographic pole, the Northern Sledge Party’s feat became nearly coequal with his own Farthest South. “I congratulate you and your comrades,” King Edward VII telegraphed to Shackleton on the Nimrod’s return to New Zealand, “on your having succeeded in hoisting the Union Jack . . . within a hundred miles of the South Pole, and the Union Jack at the South Magnetic Pole.” In the RGS’s official journal, Mill depicted David’s north as “no less interesting” than Shackleton’s south.51 In his widely popular book and lectures about the expedition, Shackleton, always a savvy promoter, gave almost as much attention to the Northern Sledge Journey as to his own southern one. Some muddled press accounts made it appeared that Shackleton had made both treks. Britain’s long Magnetic Crusade, begun in the first years of Victoria’s long reign and wrapped in popular notions of science and empire, finally reached its Jerusalem with three cheers for the king somewhere near the South Magnetic Pole.

Discovery expedition sledging routes, south, west, and east (1901–4), from Robert Scott’s Voyage of the “Discovery” (New York, 1905).