SCIENCE CARRIED AUTHORITY IN THE ENGLISH-speaking world at the time Discovery sailed, and Discovery’s sponsors claimed the mantle of science for their work. Yet Victorians contested the meaning of science by ascribing it all manner of means and ends. In late-nineteenth-century Britain, virtually anything might be called scientific by someone interested in touting its virtues.

Although there was some common ground over what constituted good science in the context of Antarctic exploration, as drafted by its sponsors, the Discovery expedition’s instructions gave equal emphasis to two forms of research from different scientific traditions. The Royal Society, which increasingly was composed of professional scientists committed to experimental research and the systemization of knowledge in physics, biology and the other natural sciences, called for an Antarctic magnetic survey. The instruction “to determine, as far as possible, the nature, condition, and extent . . . of the south polar lands,” on the other hand, articulated the aims of the Royal Geographical Society, an association of amateurs devoted to continuing a tradition of mapping, fact gathering, and specimen collecting by explorers and naturalists in the service of empire. Clements Markham and other RGS leaders viewed their society’s activities as scientific even though some in the Royal Society might dismiss them as craft or even hobby. At the RGS’s urging, the expedition’s instructions authorized “geographical discovery and scientific exploration by sea and land” in the Antarctic quadrants surrounding the Ross Sea, which at Markham’s request were assigned to Britain by the 1899 International Geographical Congress.1

Neither the Royal Society nor the RGS wanted a record-chasing dash to the pole or mere adventure travel. Both demanded a thoroughly scientific enterprise, though they had diverging ideas of what that might mean. For the Royal Society, it typically meant the collection of data in the form of numerical tables or graphs for analysis by experts in Britain. In contrast, the meaning the RGS placed on such terms as “geographical discovery” and “scientific exploration” grew out of its seventy-year history during Britain’s century of empire. A maker of maps, the society took an approach toward Antarctica that was largely shaped by its experience with Africa—an experience that, by 1900, had made geographical explorers into British national heroes.

Founded in 1830 as little more than a social club, lecture hall, and map room for English gentlemen interested in world travel, in the 1850s the RGS began to take a central role in shaping Britain’s conceptions of geography when it welcomed David Livingstone back from his missionary travels and researches in southern Africa. The RGS had neither dispatched nor trained Livingstone for geographical work, but the society’s able and ambitious president, the gentleman geologist Roderick Impey Murchison, recognized the restless Scottish missionary’s extraordinary gift for African fieldwork and helped mold him into the living exemplar of a scientific British explorer for a Christian imperial age. In an era when Britons wanted heroes, both men loomed large. The collaboration of Murchison and Livingstone in opening central Africa to Europe set the pattern that Markham and Scott would follow in Antarctica a generation later.

Before Livingstone, the RGS had served the interests of maritime travelers more than those of empire builders. Following the loss of the American colonies in 1783 and a long war with Napoleonic France ending in 1815, many Britons had little stomach for acquiring a global land-based empire. But Britain’s navy ruled the seas, and its far-flung commercial interests included trading posts and whaling stations around the world. Beginning with James Cook’s first voyage in 1768, the Admiralty launched expeditions to survey coasts, harbors, and seas for military and commercial purposes. Young naturalists destined for greatness, like Joseph Banks, Charles Darwin, Joseph Hooker, and T. H. Huxley, might accompany these voyages, but their fieldwork was limited by sailing schedules. Yet the international reach of British commerce facilitated the spread of British travelers, especially following the introduction of ocean-going steamships during the second quarter of the nineteenth century. Soon the world was teeming with Britons chasing remote destinations.

For most of its first two decades, the RGS remained an elite dining club where wealthy English adventurers, diplomats, and military officers swapped travel stories over exotic dishes. During the mid-1830s, under the leadership of Admiralty Second Secretary John Barrow—who showed greater interest in dispatching navy expeditions to the Arctic than in nurturing land exploration—the society settled into its roles as an association of well-heeled geography enthusiasts and a repository of maps, information, and instruments for explorers, travelers, and the military. Membership and financial resources dwindled throughout the 1840s until Murchison took charge in 1851 and quickly made the RGS into a command post for land exploration and global empire. Public lectures by returning explorers became its main drawing card, with priority access for members.

A field geologist who did important work in tracing the rock formations of Europe, Murchison presided at various times over the Geological Society of London, Britain’s Geological Survey, and the British Association for the Advancement of Science as well as the RGS. Geography for him was closely allied with geology in the scientific study of the earth, its features, and its peoples. Geological surveys looked below the surface to map the distribution and composition of mountain ranges and rock strata, with a practical eye for coal seams and beds of mineral-bearing rock. Physical geography focused on the surface by mapping topography, describing features, and plotting places by their longitude, latitude, and altitude. Human geography added the mapping and description of peoples and cultures. Murchison believed that both geological and geographical information could guide British colonial expansion and, when engagingly presented by intrepid explorers, also entertain domestic audiences. “His sophisticated manipulation of publicity techniques,” wrote Murchison’s biographer, Robert A. Stafford, “transformed the ailing Society into a theatre of national suspense, a company of talented adventurers purveying high drama in exotic settings.”2

Still largely unmapped by Europeans beyond its coasts and of grave concern to British Christians opposed to the slave trade, Africa took center stage in the RGS theater. As early as 1852, Murchison speculated that an elevated central basin, filled with lakes and rivers, lay beyond the continent’s forbidding rim of malarial coasts, barren deserts, and rugged mountains. The rivers running from the interior to the coast, particularly the Nile, which would connect these highlands to the Mediterranean, excited his interest as possible routes for British commerce and colonization.

“Wherever the sources of the Nile may ultimately be fixed and defined, we are now pretty well assured they lie in lofty mountains at no great distance from the east coast,” Murchison declared in his 1852 RGS presidential address. “The adventurous travelers who shall first lay down the true position of these equatorial snowy mountains . . . and who shall satisfy us that they not only throw off the waters of the White Nile to the north, but some to the east, and will further answer the query, whether they may not also shed off some streams to a great lacustrine and sandy interior of this continent, will be justly considered among the greatest benefactors of this age to geographical science!”3 While the RGS also backed expeditions to Asia, Australia, and other far-off regions during Murchison’s sixteen-year tenure as president, which included all but five years from 1851 to 1871, Africa received its most sustained attention, and lectures on African Nights typically drew the largest crowds. Membership doubled and then doubled again.

Before turning to Livingstone, Murchison tapped the intrepid but irascible Richard Francis Burton and his sometime companion John Hanning Speke to seek the Nile’s source in an area of east-central Africa unknown to Europeans but rumored to contain great lakes, high mountains, and a substantial native population exploited by Arab slave traders. This region especially interested Murchison and other British Christians opposed to slavery. While the Royal Navy had largely suppressed the Atlantic slave trade from West Africa, trafficking in humans continued in East Africa. Abolitionists hoped that British incursions into the region might disrupt the practice by promoting alternative forms of commerce.

A master linguist, Burton gained fame as a Victorian adventurer in 1853 when, disguised as an Arab pilgrim, he gained entry into the Islamic holy cities of Medina and Mecca, which were forbidden to non-Muslims under pain of death. Shadowed by accusations that he killed an Arab boy who had uncovered his ruse, Burton lived to tell the tale in a sensational travel narrative. This triumph led Murchison to invite him to organize an RGS expedition with Speke to find the Nile’s source in the great lakes of central Africa. Their first attempt ended with an attack by Somalis that left one companion dead, a javelin piercing though Burton’s two cheeks, and Speke escaping capture with over a dozen stab wounds. On their second attempt, Burton reached Lake Tanganyika in 1858 too sick to continue. Partly deaf after cutting a burrowing beetle from his ear and temporarily blinded by disease, Speke pushed on to find and rename Lake Victoria. He and Burton were the first Europeans to reach either lake, but the loss of their instruments prevented a complete survey. They split over whether Lake Victoria fed the Nile and returned without finding its outlet.

Drawing large audiences to their separate RGS lectures, Burton and Speke became celebrities in Britain. Neither represented the Victorian ideal. Some listeners were disturbed by Burton’s crude depictions of alleged African depravity, others by his romantic embrace of Arab culture. His graphic portrayal of native sexual practices made some shocked Victorians suspect he had participated in them. And his persistence in challenging Speke’s claim to have found the Nile’s source in Lake Victoria diminished the stature of both men. A follow-up RGS expedition by Speke—who seemed to make enemies easily—failed to settle the matter. “Poor Speke,” Livingstone wrote, “has turned his back on the real sources of the Nile.”4 The embattled explorer died from a self-inflicted gunshot wound in 1864 while hunting on the eve of a scheduled debate with Burton at the BAAS’s annual meeting, before an expected audience of thousands. The way was left open for David Livingstone.

Livingstone was made to order for Victorian tastes and soon became Murchison’s most-favored explorer. He had been born in poverty, the son of a peddler, near Glasgow in 1813 and taught himself languages and science while working twelve-hour shifts as a child laborer in a cotton mill. Beaten by his pious Protestant father for reading travel and science books rather than solely religious ones, Livingstone grew to accept the Bible and science as complementary paths toward truth, and chose missionary travel as his way to serve both God and humanity. “Religion and science are not hostile,” he affirmed in his first book about African travel, “but friendly to each other, fully proved and enforced.”5 Like many British evangelicals of the day, Livingstone hated the African slave trade and longed to carry civilized Christian ways to what he perceived as heathen lands. Never an effective preacher, he earned a medical degree to make himself useful on the mission field and accepted a call to the South African outback in 1840.

From his base at a mission on the northern edge of Britain’s Cape Colony, Livingstone was drawn north toward people and places unknown to Europeans. Evangelizing as he went, he relied heavily on local porters and guides, with whom he often established strong bonds. Europeans avoided the interior of sub-Saharan Africa out of fear of disease and a common misperception that the region was barren desert. Livingstone had an iron constitution that seemed able to endure all manner of illness and a sustaining faith that he could find in central Africa a fertile highland, free of tropical diseases, where European trade and missions could flourish. Never lacking in ambition, he saw commerce, Christianity, and civilization as conjoined means to stop the slave trade and redeem Africa.

In 1850, reports of Livingstone’s travels began filtering back to the RGS through his letters to the London Missionary Society. “Our journey across the desert was one of great labour and suffering,” he wrote in one letter about a six-hundred-mile trek with two British hunters across the Kalahari Desert to the river Botetle and Lake Ngami, in present-day Botswana. Neither body of water had been seen by Europeans. The letter, read to the RGS in 1850, contained latitude readings for various points taken with a borrowed sextant and altitude estimates based on the boiling point of water. It described a land of “gigantic trees, some of them bearing fruit quite new to us,” lakes and rivers swarming with “large shoals of fish,” and a race of people with a “frank and manly bearing.”6 This account differed sharply from the portrait of African desolation and savagery painted by Burton and other early explorers. It was what Murchison and many empire-minded British Christians wanted to hear.

For “discovering” Lake Ngami, the RGS awarded Livingstone a twenty-five-guinea prize, which he used to buy his own sextant and surveying equipment. “The fact that the Zouga is connected with other large rivers flowing into the lake from the North,” Livingstone wrote in his letter, “opens the prospect of a highway capable of being easily traversed by boats to an entirely unexplored, but, as we were told, populous region. The hopes which that prospect inspires in behalf of the benighted inhabitants might subject me to the charge of enthusiasm—a charge, by the way, I wish I deserved—for nothing good or great has ever been accomplished in the world without it.”7 Buoyed by hopes of reaching unsaved souls and unknown lands, he ventured out again in 1852.

Livingstone’s fame grew out of this 1852–56 expedition, which became the subject of his best-selling 1857 book, Missionary Travels and Researches in South Africa, and transformed him into a near-mythic hero in Britain. On a journey chock-full of hair-raising adventures, he inscribed a T-shaped track across a vast expanse of southern Africa well known to African and Arab traders but never before visited by Europeans. First he trekked north to the Zambezi River, in what would become Britain’s rich Rhodesian colonies. Then he turned east to reach the Portuguese colony of Angola on the Atlantic Coast, from where he dispatched letters detailing his discoveries to the RGS, which rewarded him with its highest award, the Queen’s Gold Medal. When presenting this award, Murchison reportedly said of the still absent Livingstone, “There was more sound geography in the last sheet of foolscap which contained the results of your observation than in many imposing volumes of high pretentions.”8

Rather than return by sea from Angola, after recovering from a near-fatal illness, Livingstone retraced his steps to the Zambezi and then followed this river west to the Portuguese colony of Mozambique on the Indian Ocean, where a British warship waited to carry him home. On this final leg of his inland travels, Livingstone became the first European to see the magnificent falls of the Zambezi, which he named Victoria in honor of his queen. “No one can image the beauty of the view from anything witnessed in England,” he wrote of these falls. “It had never been seen before by European eyes; but scenes so lovely must have been gazed upon by angels in their flight.”9

Livingstone’s four-year trek took on epic proportions in the annals of European travel. Although presumably accomplished by Africans and perhaps by Arabs, no record exists of anyone crossing Africa before Livingstone: he did it one and a half times. Further, he kept detailed geographical records along the way, including regular calculations of longitude by lunar occultation, latitude by sextant, and altitude by the temperature of boiling water. “I never knew a man who, knowing scarcely anything of the method of making geographical observations, or laying down positions, became so soon as adept that he could take the complete lunar observation, and altitudes for time, within fifteen minutes,” the Astronomer Royal and RGS medalist Thomas Maclear commented in 1856. “His observations of the course of the Zambezi, from Stesheke to its confluence with the Lonta, are the finest specimens of geographical observation I ever met with.” These were the data demanded by mid-nineteenth-century scientific geographers and sought by the RGS. “To no one in modern times have this country and the world been more indebted for geographical knowledge and researches,” an RGS report declared even before his great journey ended.10 Livingstone’s findings led to the first serviceable map of the region and filled a large blank space on the European globe.

By the time he reached Mozambique in 1856, Livingstone was sending his reports directly to Murchison, who saw them as confirmation of his theory that Africa had an elevated central basin. “I thank you most heartily for having made me your correspondent,” he responded. “I shall indeed have the liveliest pleasure in talking over your verification of my theoretical speculations on the ancient and modern outline of Africa.” In a further reply, Murchison hailed Livingstone’s work as “the greatest triumph in geographical research which has been effected in our times.”11

Best of all for Murchison, Livingstone reported finding disease-free, fertile highlands near Victoria Falls that might provide a regional base for British trade and missions. The two men shared the dream that such a colony could undermine the local slave trade, which Livingstone grimly documented in his letters. As if to claim the place for British pastoral pursuits, he planted a hundred peach and apricot pits and left them in the care of a native farmer, noting that “I have great hopes of Mosioatunya’s abilities as a nurseryman.”12 Cotton, he added, could become a staple crop that would reduce British dependence on the product from the slave-owning American South. From Victoria Falls, Livingstone followed the Zambezi for most of its course to the ocean. It offered, he claimed, a navigable route from the sea to this potential British outpost. This assertion was Livingstone’s greatest boast, a boon to empire and a coup for the RGS. It was also his greatest geographical blunder.

Livingstone received a hero’s reception in Britain. Humble in tone yet with a flair for publicity—he wore his simple black coat and explorer’s cap even for his audience with the queen—he told a story combining British aspirations for science, religion, adventure, and empire. His rise from poverty, Scottish roots, and missionary service appealed to Britons across class, ethnic, and religious lines. Even before he reached London, “in consideration of the probable interest of your work,” Britain’s leading publisher of science and exploration, John Murray, offered him an extraordinary contract for an account of his travels: two-thirds of the profits, a higher rate than Murray would pay Charles Darwin for On the Origin of Species three years later.13 Missionary Travels and Researches, which Livingstone dedicated to Murchison, sold phenomenally well. The account even won over Charles Dickens, who had long satirized Victorian evangelicals as ignoring real domestic needs in favor of abstract foreign ones. In a rave review, Dickens praised the book as “a narrative of great dangers and trials, encountered in a good cause, by as honest and as courageous a man as ever lived.”14 Throughout Livingstone’s stay in Britain from 1857 to 1862, throngs cheered Livingston’s every public appearance and flocked to his lectures.

For his much-anticipated first public address in Britain, Livingstone passed over the London Missionary Society, which had initially sponsored his travels for religion, for the RGS, which had commandeered them for science. “The society’s rooms were crowded to excess,” the Times of London reported of Livingstone’s reception at the RGS by a “distinguished assembly” of aristocrats, government officials, military officers, and explorers that cheered virtually his every remark.15

Murchison, chairing the session, introduced Livingston “as the pioneer of sound knowledge, who, by his astronomical observations, had determined the site of numerous places, hills, rivers, and lakes, nearly all hitherto unknown, while he had seized upon every opportunity of describing the physical features, climatology, and even the geological structure of the countries he had explored, and pointed out many new sources of commerce.” In reply, Livingstone declared, “May I hope that the path which I have lately opened into the interior will never be shut, and that, in addition to the repression of the slave trade, there will be fresh efforts made for the development of the internal resources of the country.” In such expressions, Murchison’s and Livingstone’s minds met and their purposes merged; they became lifelong friends and collaborators. “Both men were Scots, both were dedicated Christians, dedicated patriots and dedicated geographers,” RGS historian Ian Cameron wrote, “and for the rest of his career Livingstone—like Scott a couple of generations later—became the chosen child of the Society.”16 As a self-sacrificing explorer who took extreme risks for geographical science, Livingstone became Scott’s model.

Livingstone’s later travels were anticlimactic. From 1858 to 1865 he led a large-scale, government-funded expedition to ascend the Zambezi by steamboat toward his proposed highlands colony. Unfortunately, on his earlier descent, Livingstone had bypassed a critical stretch of the river that included impassable rapids. His return journey foundered on these rocks. The Times, which had once celebrated Livingstone, now demanded his head. “We were promised trade, and there is no trade,” the news voice of the empire complained in 1863. “We were promised converts to the Gospel, and not one has been made.” The government ultimately recalled the expedition, but not before Livingstone’s wife died of fever and the expedition’s artist and ship captain both resigned. “Dr. Livingstone is unquestionably a traveler of talent,” the Times concluded, but “it is now plain enough that his zeal and imagination much surpass his judgment.”17

Murchison did not abandon his friend. In 1866, the RGS sent Livingstone to Africa to find the source of the Nile. Accompanied by African guides and porters, he became increasingly isolated in the Great Lakes region of central Africa. After rumors of his death reached London in 1871, the RGS dispatched a relief party. A Welsh-born journalist sent by the New York Herald to cover the story, Henry Morton Stanley, reached Livingstone first. Sick and out of supplies, the beleaguered explorer had sought refuge in the slave-trading town of Ujiji near Lake Tanganyika. “Dr. Livingstone, I presume?” the journalist asked in an affected British understatement. “Yes, that is my name,” was the reply.18 With supplies from Stanley, Livingstone continued his ever more desultory wanderings. He died in 1873, afflicted by multiple tropical diseases. Devoted attendants buried his heart where he died and carried his sun-dried corpse a thousand miles to the coast for transport to London, where he lay in state in the RGS map room before being buried among England’s heroes in Westminster Abbey, the only explorer so honored.

Other European explorers extended the reach of Western geography during the late 1800s, but until Scott, none became such a popular hero as Livingstone. By the time of Scott’s Discovery expedition, an explosion of imperial expansion had carried European explorers deep into every continent except Antarctica, and their sponsoring nations had colonized Africa and much of Asia. Respected but not beloved, Stanley—who returned to Africa in the service of European imperialists, confirmed Speke’s claim that the Nile flowed out of Lake Victoria, and traced the Congo River from its source to the sea—pushed empire as much as discovery. “Geography,” he asserted in 1884, is “a science which points with commonest inductions to . . . the paths which commerce ought to follow” and “has been and is intimately connected with the growth of the British Empire.” His African work done, the RGS greeted the return of Stanley to Britain in 1890 with a grand ceremony at London’s cavernous Royal Albert Hall. The society’s librarian depicted the event as a celebrating “the completion of the task [the RGS] had laboured upon in setting the great features of African hydrography and orography.”19 Society members had reason to cheer. Save for Antarctica, Europeans had mapped the world.

The large blank space at the bottom of European globes had not stood out in 1850. At that time, the only distinct lines on Antarctic maps traced Ross’s route along the Victoria Land coast and the Great Ice Barrier, outlined the whaling grounds of the Antarctic Peninsula and Weddell Sea, and marked a few isolated shores and islands supposedly spotted by sailors. These lines delineated less than one-tenth of the actual coast and none of the interior. But there were other gaps on European globes. The Arctic coast remained largely uncharted even though most of it was nominally under European rule. Virtually the entire interior of Africa, much of central Asia, and parts of the Americas appeared on European-drawn maps either as blank spaces or filled in with imagined features such as Ptolemy’s fabled Mountains of the Moon in central Africa.

By 1900 much had changed. Late in life, the great novelist of empire Joseph Conrad recalled the profound experience of “entering laboriously in pencil the outline of [Lake] Tanganyika on my beloved old atlas, which, having been published in 1852, knew nothing, of course, of the Great Lakes. The heart of its Africa was white and big.” Not only did lakes, rivers, and towns replace trackless desert on European maps of Africa, the entire continent except tiny Liberia and ancient Abyssinia became a jigsaw puzzle of European colonies, most of them British or French. Similarly, Russians pushing south from Siberia and Britons pushing north from India had filled in European maps of central Asia. The story repeated itself elsewhere. Empire drove geography and geography drove empire. As early as 1864, Prime Minister William Gladstone cautioned RGS members, “Gentlemen, you have done so much that you are like Alexander, you have no more worlds to conquer.” Gladstone overlooked Antarctica. RGS historian Robert Stafford more precisely commented, “Except for the poles, the explorers had nearly worked themselves out of a job by the late 1880s.”20 For Clements Markham, this distinction made a considerable difference.

In the period after Murchison’s death in 1871, Markham probably had greater practical familiarity with geography than any other Briton. He had lived it. Following in the wake of empire, by 1890, the widely traveled Markham had participated in British expeditions to the Arctic, South America, Asia, and Africa. He had also served under Murchison and others as RGS secretary from 1863 to 1888. Invited to contribute the entry on “The Progress of Geographical Discovery” to the classic 1875–89 edition of Encyclopaedia Britannica, Markham concluded his synopsis by declaring that along with surveying the deep-sea floor and the remote interiors of Asia, Africa, South America, and New Guinea, “The great geographical work of the present century must be the extension of discovery in the Arctic and Antarctic regions.”21

Having been a nineteen-year-old midshipman on the Franklin searches in 1850, Markham turned first to promoting British Arctic exploration, which had faltered in the 1850s with the failure to find Franklin’s lost party. The initiative passed to other nations during the 1860s and 1870s, with Norwegians first circumnavigating Spitsbergen, Austrians discovering Franz Josef Land, and Swedes first sailing the Northeast Passage. Starting in 1865, Markham led a group of self-styled RGS Arctic Associates who lobbied the government to resume exploration in the far north. “A mere quest for the Pole was not an aim which would secure influential or intelligent support,” he said of this effort. “The objects of Arctic exploration, in these days, must be to obtain valuable scientific results.” A cousin who joined the resulting expedition later recalled that Markham had “persistently pleaded” the cause for ten years before achieving “complete success.” The approach worked. Explaining the decision to send an expedition north, Prime Minister Benjamin Disraeli specifically cited “the scientific advantages to be derived from it.”22 The pattern repeated itself three decades later for Antarctica, with Markham again pushing scientific justifications to the fore.

When the British Arctic expedition sailed in 1875, its leader, George Nares, invited Markham to join it as far as Greenland and assigned his cousin to lead its winter sledge journey toward the pole. “The Arctic Expedition achieved all that [the RGS] Council desired,” Markham later claimed. “It succeeded in crossing the threshold of the unknown region, its ships attained a higher latitude than any other vessel has ever reached, they wintered further north than any human being has ever been known to have wintered before, and Captain [Albert] Markham planted the Union Jack on the most northerly point ever reached by man.” Clements Markham clearly cared about these firsts and lauded the experience they afforded for naval officers, but he also hailed what he saw as the expedition’s scientific results. In his list, they included “the discovery of 300 miles of new coastline,” magnetic and meteorological observations at two stations, studies of tides and ice flows at high latitude, geological and biological collections, and “the discovery of a fossil forest in 82° North latitude.”23 He was putting the best possible face on an otherwise disappointing effort.

Markham gained a further chance to promote polar exploration in 1893, when he unexpectedly became the RGS president. His ascension followed a bitter row over the admission of women members that split the society. Aligned with tradition but taking no part in the dispute due to his absence on an overseas trip, Markham unknowingly emerged as a compromise candidate. He held the post for twelve years, during which time no women joined the club. In a manner recalling both the African expeditions launched by Murchison and his own Arctic endeavors, Markham focused the society’s attention on the large blank space at the bottom of world maps. With no one living there and scant prospect of anyone doing so, exploring Antarctica would serve little commercial, colonial, or evangelical religious purpose, but for him geography had a higher calling. “Four main causes have led to geographical discovery and exploration,” he wrote in his Encyclopaedia Britannica article, “namely, commercial intercourse between different countries, the operations of war, pilgrimages and missionary zeal, and in later times the pursuit of knowledge for its own sake, which is the highest of all motives.”24 The RGS’s Antarctic researches fell squarely in the fourth category, with Markham having his own view of what constituted knowledge for its own sake.

In the 1890s, Markham envisioned a new Antarctic expedition yielding the same sorts of scientific results as the 1875 Arctic expedition, only more and better. Geographical mapping and surveying unexplored territory came first for him, and then magnetic, meteorological, oceanographic, geological, and biological observations. Nares had balanced all of these pursuits in his 1875–76 Arctic expedition, and Markham went so far as to call the new expedition’s ship Discovery after Nares’s main vessel. The name captured Markham’s vision. He wanted to discover the earth’s last uncharted large landmass and bring it under the domain of geographical science.

By the time of Scott’s 1901–4 expedition, the RGS had refined its concept of geographical discovery and encapsulated it in a guidebook, Hints to Travellers. “The advance of geographical exploration and discovery during the last fifty years has been so rapid and continuous that there remain at the present time few parts of the Earth’s surface that are entirely unknown,” the 1906 edition began. “A man who only makes a hurried journey through some imperfectly known district, without proper instruments or previous training, and who is able, consequently, only to bring back with him a rough prismatic compass sketch of the route he has taken, unchecked by astronomically determined or triangulated positions, will, at the present time, find that he has not rendered any great service to geography.” The book’s 1901 edition declared, “The intending traveller who proposes to undertake the survey of an unexplored country should . . . have a knowledge of plane trigonometry, and those computations of practical astronomy which are necessary to enable him to fix his position in latitude and longitude.”25 Loaded with mathematical tables, equations, and instructions, Hints to Travellers accompanied every British Antarctic expedition. Scott carried the 1901 edition on the Discovery; Shackleton and Scott took the 1906 edition on their later expeditions.

Although widely used by explorers and originally coauthored in 1854 by Charles Darwin’s captain on the Beagle expedition, Robert Fitzroy, Hints to Travellers took its inspiration from the growing number of Victorian tourists who wanted to join in the enterprise of geography. “One of the results of the rapid multiplication of lines of ocean steamers and of railways in distant seas and far-off countries has been to make it easy for men of comparatively brief leisure to undertake a share in exploration in the course of a vacation tour,” the 1893 edition explained. “India has become commonplace, and Members of Parliament spend their holidays in Siberia, Brazil, Korea, or the Antipodes. The vacation travellers, or tourists, who are tempted by modern facilities into imperfectly-known regions are numerous, and their opportunities for collecting valuable information are great.”26

In the British scientific tradition of amateur fact-gathering, the RGS envisioned trained travelers supplementing the findings of professional explorers in the grand mission of mapping the globe. Accordingly, in addition to updating and republishing its guidebook for nearly a century, the RGS offered classes for travelers in geographical fieldwork. The core course, a required prerequisite for all the others, was titled “Surveying and Mapping, including the fixing of positions by Astronomical Observations.”27 Preparing for their expedition, Scott and his officers took customized versions of these courses. The RGS expected the explorers to lay down accurate maps of the territory they covered even if no one was ever likely to use them for commerce, conquest, or converting the nonexistent natives.

By this time, the compulsion to map had overtaken the commercial, colonial, or evangelical purposes that mapping once served. In his Encyclopaedia Britannica article, Markham may have called it “the pursuit of knowledge for its own sake,” but it was also for the sake of people like Markham. They wanted to know the precise location and altitude of Antarctic mountains, glaciers, and capes that they would never see and have them named for themselves and their kind. Scott and his men became their agents in this task. Of course, the Discovery expedition had other scientific goals, such as the magnetic survey that brought the Royal Society aboard and justified its government funding, but for Markham and the RGS, mapping was central to the mission.

The RGS equipped the Discovery expedition with the full range of tools then used to make topographical maps. These included sextants, theodolites, aneroids, telescopes, chronometers, compasses, plane tables, and various measuring devices—all in portable sizes for sledging. Hints to Travellers gave information for their use, causing Scott to panic when he lost his copy on the long Western Sledge Journey to the Polar Plateau. “The gravity of this loss,” he wrote, “can scarcely be exaggerated. . . . We expected to be, as indeed were, for some weeks out of sight of landmarks. In such a case as this the sledge traveler is in precisely the same position as a ship or boat at sea: he can only obtain a knowledge of his whereabouts by observations of the sun or stars, and with the help of these observations find his latitude and longitude. To find the latitude from an observation of a heavenly body, however, it is necessary to know the declination of that body, and to find the longitude one must have not only the declination, but certain logarithmic tables. . . . Now, all these necessary data are supplied in an excellent little publication issued by the Royal Geographical Society and called ‘Hints to Travellers.’ “Scott was forced to rely on dead reckoning to make it out and back, but returned without a reliable record of his route.28

The Discovery expedition’s two Western Sledge Journeys, the first led by Armitage in 1902 and the second by Scott in 1903, addressed one of the three principal geographical aims left over from Ross’s 1839–43 expedition. Ross had sailed into the Ross Sea from the north. “He had found a high, mountainous country to the west and an ice wall to the south,” Scott explained in laying out his expedition’s geographical goals. “Ross was in a sailing ship and only saw things dimly and at a distance. Beyond this nothing was known. The geographical problem was, therefore, in brief, to find out what lay to the east, to the west and to the south of what Ross had seen.”29

To the west on their Western Sledge Journeys of 1902 and 1903, the explorers found an ice sheet or Polar Plateau extending beyond the Victoria Land mountains. Scott had hoped to determine its extent by sending a party across it to the sea but fell far short of this utterly unrealistic goal. Armitage’s 1902 party struggled simply to reach the plateau, and Scott’s 1903 party covered only two hundred miles of its surface before turning back. “All we have done is to show the immensity of this vast plain,” Scott wrote on the final day of his party’s outward march. “Greenland, I remembered, would have been crossed in many places by such a track as we have made.” Antarctic’s ice sheet was much larger than anything in the north, he concluded. Gauging the altitude, Armitage reported it as “9,244 feet by theodolite angles, 8,727 feet by aneroids, the mean height by the two methods being 8,985 feet.”30 Scott found it 8,900 feet above sea level by aneroids, with virtually no change as he traversed it.

Assuring his expedition’s geographical significance at the outset, Scott looked beyond Ross to the east before establishing winter quarters at McMurdo Sound, which both men initially described as a bay. Ross had discovered that navigable inlet between Ross Island and the Victoria Land coast, sailed deep into it, reported seeing mountains on the southern horizon, and then headed east along the Ice Barrier until he sighted land in the distance. With this, he claimed to have charted the three sides of the Ross Sea. Staying well back from the barrier in his sailing ships, Ross described it as a “solid-looking mass of ice” without “any rent or fissure” rising 150 to 200 feet from the sea. He did not know if it floated or was mostly grounded; or whether it was composed largely of compressed sea ice or glacial outflow. To him it constituted one of the world’s geographical wonders, and geographers had wondered about it ever since. “Perhaps of all the problems which lay before us,” Scott wrote, “we were most keenly interested in solving the mysteries of this great ice-mass.”31

Sailing further south than Ross in McMurdo Sound in January 1902, Scott resolved that the mountains Ross reported seeing in the southern horizon were optical illusions and did not supply a backdrop for the Ice Barrier. Then he turned his attention on the barrier itself by sailing east along it. “In order that nothing important should be missed, it was arranged that the ship should continue to skirt close to the ice-cliff; that the officers of watch should repeatedly observe and record its height, and that thrice in the twenty-four hours the ship should be stopped and a sounding taken,” Scott wrote.32 They found that the Ice Barrier’s sea edge extended for 490 miles.

Little now seemed as Ross had reported. “On steaming along the barrier, we soon found that Ross had exaggerated not only its height, but its uniformity,” Scott noted. Discovery observers calculated that the height of the Ice Barrier’s sea edge varied from 30 to 280 feet. “Soundings both over and under 400 fathoms. Barrier sometimes very broken and rugged in outline,” Scott jotted in his diary. No one could see land at Ross’s farthest east, which scotched another of his findings. The Discovery sailed on to where the barrier visibly terminated on solid ground, which Scott named King Edward VII Land for his monarch. Sizing up this newfound land from aboard ship, Scott noted, “With a sextant and the distance given by four-point bearing, we were able to calculate the altitude as between 2,000 and 3,000 feet.”33 Accumulating sea ice and deteriorating weather kept the explorers from landing.

Discovery instead tied up at a blight in the Ice Barrier roughly eighty miles west of Edward VII Land. Armitage took a six-person sledge party south for an overnight outing that covered about seven miles while the ship’s crew inflated a tethered surveillance balloon. “The honour of being the first aëronaut to make an ascent in the Antarctic Regions, perhaps somewhat selfishly, I chose for myself,” Scott confessed, “and as I swayed about in what appeared a very inadequate basket and gazed down on the rapidly diminishing figures below, I felt some doubt as to whether I had been wise in my choice.” Rising eight hundred feet, Scott saw an undulating expanse of ice extending as far as he could make out with binoculars. The ice waves ran parallel to the barrier’s sea edge at roughly two-mile intervals and, according to Armitage, rose and fell sharply. “Rather than crossing a series of undulations, the party had appeared to be travelling on a plain intersected by broad valleys, the general depth of which as measured by aneroid was 120 feet,” he reported.34 Although clearly an ice shelf or sheet, the explorers persisted in using the term “Ice Barrier” for the entire frozen mass. Shackleton also went up in the balloon, followed by three others before a leak ended the experiment for good. With winter coming on, Discovery returned to McMurdo Sound.

Sailing along the Great Ice Barrier’s front could not reveal its true extent. The explorers’ most revealing glimpse of this came from Scott’s record-smashing Southern Sledge Journey of 1902–3. It generated the expedition’s most memorable geographical findings and, more than any other event during the Discovery expedition, made Scott famous. It was for him what the Zambezi trip had been for Livingstone: the first public display of his mettle.

While the British scientists and scientific societies promoting the renewal of Antarctic research asserted that the Discovery expedition would be all about science and geography rather than a record-chasing dash to the South Pole, Markham and Scott surely had that feat in mind from the outset, even if they did not admit it. Markham later conceded that “all mention of the south pole was carefully avoided” in the official expedition instructions that he negotiated with the Royal Society. Reaching the pole could not happen at the expense of science. But the instructions did authorize Scott to determine “the nature, condition, and extent of that portion of the south polar lands” within the two Antarctic quadrants encompassing the Great Ice Barrier, and those quadrants extended to the pole. Further, Markham’s initial draft instructions, which he maintained were “practically” the same as the final ones, authorized “a complete examination of the ice mass which ends in the cliffs discovered by Sir James Ross.”35

At the time, some geographers thought the barrier ice shelf might extend to the South Pole. If it did, then (within the scope of the expedition’s mandate) a small, fast-moving sledge party conceivably could get there and back in three months by racing across the Ice Barrier either on skis, the way Nansen had crossed Greenland, or by using dogs as Peary was doing in the Arctic. At least the party could set a new Farthest South record while extending the boundaries of geographical knowledge. Scott must have discussed both options when asking the expedition’s junior physician and artist, Edward Wilson, to join his Southern Sledge Party, which would depart in early November 1902. “It must consist of either two or three men in all and every dog we possessed,” Wilson reported Scott saying. “Our object is to get as far south in a straight line on the Barrier ice as we can, reach the Pole if possible, or find some new land, anyhow do all we can in the time and get back to the ship by the end of January.”36 Scott and Wilson settled on Shackleton as the third man.

With these mixed goals in mind, the Southern Party left the expedition’s Hut Point base on November 2 with five sledges, nineteen sled dogs, and nearly a ton of supplies, food, and instruments. A twelve-man support team left the base three days earlier to stock depots but turned back in mid-November. All were together on the thirteenth, however, when Scott’s readings showed they had nearly reached the Seventy-ninth Parallel and therefore passed Borchgrevink’s old Farthest South. “The announcement of that fact caused great jubilation,” Scott noted in his diary. This marked about a one-degree (or seventy-mile) advance from Hut Point’s latitude at 77° 47′ south. After the support team left two days later, he added, “We are already beyond the utmost limit to which man has attained: each footstep will be a fresh conquest of the great unknown. Confident in ourselves, confident in our equipment, and confident in our dog team, we can but feel elated with the prospect that is before us.”37

Having virtually no experience on skis, driving sled dogs, or crossing an ice shelf, Scott should have felt less confidence. Almost immediately, the dogs began to fail because of tainted food and poor handling. Soon the men were doing much of the hauling, in a relay system that involved moving half of the load at a time and returning for the other half—three miles covered for each mile gained. As each dog failed, Wilson killed it and fed the carcass to the others until none of them were left. Scott gave the orders but could not bear to watch. Having packed light for quick travel, the men ran so low on food that they could think of little else. “Conversation runs constantly on food. We are all so hungry,” Wilson noted while yet on the outbound journey. It grew much worse. Scurvy stalked them by the end, especially Shackleton, who ultimately could not help haul the sledges. Wilson suffered extreme snow blindness. “I never had such pain in the eye before,” he noted in his diary for the day after Christmas. “It was all I could do to lie still in my sleeping bag, dropping in cocaine from time to time.”38 Throughout the ordeal, when awake in their small tent after supper or during blizzards, they often read aloud from Darwin’s Origin of Species, the book they carried along for comfort: survival of the fittest indeed.

“If there were trials and tribulations in our daily life at this time,” Scott observed, “there were also compensating circumstances whose import we fully realized. Day by day, as we journeyed on, we knew we were penetrating farther and farther into the unknown; . . . while ever before our eyes was the line which we were now drawing on the white space of the Antarctic chart.” They drew this line with care—Scott mapping and measuring, Wilson sketching landscape, and Shackleton taking photographs—never forgetting their duty as agents of the RGS. As Wilson acknowledged in his diary, “Of course we must map out and sketch this new land.”39

The party’s route traced the Great Ice Barrier’s western edge, where it abutted the southern Victoria Land shore. No one had seen this coastline before. With magnificent mountains, inlets, and capes, it resembled the seacoast farther north—only here it was encased in ice and devoid of life. “We are now about ten miles from the land,” Scott noted on December 19. “The lower country which we see strongly resembles the coastal land far to the north; it is a fine scene of a lofty snow-cap, whose smooth rounded outline is broken by the sharper bared peaks, or by the steep disturbing fall of some valley.”40 Twice the men tried to reach the nearby shore to collect geological specimens, but the broken juncture between frozen land and slow-moving ice shelf left a twisted, icy ravine that they could not cross in their weakened condition.

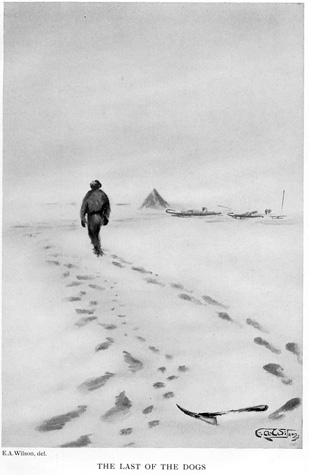

Edward Wilson’s evocative sketch of the aftermath of killing the last dog on the Discovery expedition’s Southern Sledge Journey, January 15, 1902, from Apsley Cherry-Garrard’s Worst Journey in the World (New York, 1922).

They settled for surveying the scene and documenting their observations. Scott gauged the altitude of mountains with a theodolite and named the highest peak for Markham. He also took the angle of prominent points along the way and triangulated their relative positions. “Just about 300 miles of new coast line we have got now,” Wilson noted near their Farthest South. He had captured the passing scene in detailed sketches that he later made into color paintings. “His sketches are most astonishingly accurate,” Scott declared on the spot. “I have tested his proportions by actual angular measurements and found them correct.”41 From these findings, geographers learned that Victoria Land’s coastal range continued south and potentially bisected the continent as part of what would become known as the Transantarctic Mountains. With the Southern Sledge Journey extending the known length of this range and the Western Sledge Journeys revealing what lay behind it, the Discovery expedition gave substance to the astounding idea of a vast East Antarctic Polar Plateau blanketed by a massive ice sheet of unfathomable depth.

Scott could not tell where the Ice Barrier ended in the south or how far the mountains extended because, due to insufficient food, the loss of the dogs, and the sickness of all three men, his party advanced only slightly more than 300 miles south, or about a third of the way from their ship to the pole. This mark left Scott dissatisfied. He measured the distance by sledge odometers and checked the latitude often when the sun shone through the blowing snow. “Before starting to-day I took a meridian altitude, and to my delight found the latitude to be 80°1′,” Scott wrote on November 25. “All our charts of the Antarctic Regions show a plain white circle beyond the eightieth parallel. . . . It has always been our ambition to get inside that white space, and now we are there the space can no longer be a blank.” But another month of sledging took the men only two more degrees south. They reached their limit on the last day of 1902. “Observations give it as between 82.16 S. and 82.17 S.,” Scott noted. “If this compares poorly with our hopes and expectations on leaving the ship, it is a more favorable result than we anticipated when those hopes were first blighted by the failure of the ‘dog team.’ “42 Then it was a race to the base on dwindling rations. Out and back, including relays, the party covered a total of 960 miles in three months.

Scott made the most of the record upon his return to Britain. “If we had not achieved such great results as at one time we had hoped for, we knew at least that we had striven and endured with all our might,” he wrote in his account of the Southern Sledge Journey. A similar line punctuated his public lectures, which he tellingly titled “Farthest South.” These lectures and his popular book, The Voyage of the “Discovery,” described the expedition’s other exploits as well, but Scott found the public wanting records most of all. The Southern Sledge Journey supplied them in the context of an Edwardian tale of resolve in the face of adversity. The Times hailed it as the expedition’s “most notable achievement.” Markham called it “a story of heroic perseverance to obtain great results.”43 Telling it in detail took up two long chapters of Scott’s twenty-chapter book. The tainted dog food from Norway provided a convenient villain. Owing to his “constitutional” weakness, as Scott termed it, Shackleton also shouldered a disproportionate part of the blame for the party’s turning back. “Our invalid,” Scott called him in his book.44 Shackleton never forgot the slight and complained bitterly when Scott sent him home on the relief ship after one year while the expedition remained for two.

As news of the expedition reached Europe, geographical discovery led most accounts of its significance. “The expedition commanded by Commander Scott has been one of the most successful ever to venture into Polar regions,” the Times declared. “He has added definitely to the map a long and continuous stretch of the coast of the supposed Antarctic continent. His sledge expeditions, south and west and east, have given us a substantial idea of the character of the interior.” Although some in the Royal Society complained about the expedition remaining in place for another winter after the prescribed term of coordinated magnetic observations concluded, with one critic grumbling that “Scott’s further work will be purely geographical and will not make any addition to other scientific knowledge,” Markham had only praise for the venture. “Never has any polar expedition returned with so great a harvest,” he stated. “The [geographical] discoveries alone were remarkable.” Even before the explorers returned to Britain, the RGS gave Scott its 1904 Patron’s Medal for his Southern Sledge Journey—leaving out the expedition’s other accomplishments. “There was a meeting of the Royal Geographical Society and again lots of congratulations of your having changed the maps,” Scott’s mother wrote to her son. “I am reveling in the sunshine of your success.”45

Shackleton, determined to redeem his honor, knew from Scott’s experience that geographical discovery and record sledge journeys in adverse conditions generated fame and funds. He secured financing for his 1907 Nimrod venture from Scottish industrialist William Beardmore on the promise of a push to the pole in the context of a second scientific expedition to the Ross Sea basin. “I do not intend to sacrifice the scientific utility of the expedition to a mere record-breaking journey, but say frankly, all the same, that one of my great efforts will be to reach the southern geographical pole,” Shackleton explained in a plea for supplemental support from the RGS.46 Devoted to Scott, Markham opposed helping Shackleton, but under its new president, George Goldie, the RGS endorsed the venture and lent it scientific instruments. After failing to find a suitable base near King Edward VII Land, where his party could explore less familiar territory, Shackleton wintered at Ross Island’s Cape Royds, just twenty-four miles north of Hut Point.

Setting out the following spring with three other men, four loaded sledges weighing about six hundred pounds each, and four Manchurian ponies, Shackleton’s Polar Party passed Hut Point on November 3, 1908, and followed roughly the route that Scott had blazed six years earlier. With the ponies pulling well at first, the party traveled faster than Scott’s team. But the deep snow and steady strain wore the ponies down. Collapsing one by one, they became food for the men who more and more assumed the burden of hauling the sledges. With three ponies still in harness, the party reached Scott’s southern mark on November 26, more than a month quicker than their predecessors. “We celebrated the breaking of the ‘farthest South’ record with a four-ounce bottle of Curaçoa,” Shackleton reported in his diary. “After this had been shared out into two tablespoons full each, we had a smoke and a talk before turning in. One wonders what the next month will bring forth. We ought by that time to be near our goal, all being well.”47

The terrain from this point was new, and the Polar Party began mapping it in earnest using a theodolite and compass. “The land now appears more to the east, bearing south-east by south, and some very high mountains a long way off,” Shackleton observed on November 28. The pole clearly lay due south behind those ramparts. Expedition cartographer and physician Eric Marshall “is making a careful survey of all the principal heights,” Shackleton added. “He does this regularly.”48

To their relief, the explorers soon discovered an extraordinarily broad glacial slope—the widest yet seen—ascending through the mountains toward the south. Named Beardmore Glacier for the expedition’s patron, it became the party’s route to the plateau. “The pass through which we have come,” Shackleton wrote, “is flanked by great granite pillars at least 2000 ft. in height and making a magnificent entrance to the ‘Highway to the South.’ It is all so interesting and everything is on such a vast scale that one cannot describe it well. We four are seeing these great designs and the play of nature in her grandest moods for the first time.” Large patches of sheer ice and deep crevasses complicated their ascent, with one snow-covered chasm claiming their last surviving pony, Socks. The long-suffering animal was near collapse anyway, but its abrupt disappearance into what Shackleton called “a black bottomless pit” deprived the men of needed food. Soon they faced the same problem of dwindling rations that had hindered Scott’s Southern Sledge Journey. By December 22, Shackleton prayed, “Immediately behind us lies a broken sea of pressure ice. Please God, ahead of us there is a clear road to the Pole.”49 There wasn’t.

After twenty-four days of mostly man-hauling sledges up the glacier, the Polar Party finally reached the plateau. “It is a wonderful thing to be over 10,000 ft. up at the end of the world almost,” Shackleton noted on December 28, but soon added, “Physical effort is always trying at a high altitude.” Heading south on the Polar Plateau, the party fought a constant headwind and severe altitude sickness. “The sensation is as though the nerves were being twisted up with a corkscrew and then pulled out,” Shackleton complained. “The Pole is hard to get.” Reaching it on the food available would require the party to average eighteen miles per day across the plateau, but even by reducing their load with regular depots, they never approached that mark. “The main thing against us,” Shackleton wrote on January 4, “is the altitude of 11,200 ft. and the biting wind. Our faces are cut, and our feet and hands are always on the verge of frostbite.”50 He later explained, “We had weakened from the combined effect of short food, low temperature, high altitude and heavy work.”51

Two days of hurricane-force winds and temperatures down to −40°F in early January confined them to their tent and sealed their fate. They halted on January 9 at 88° 23′ south—112 statute miles from the pole—having covered over 1,000 miles (including relays) in ten weeks and beaten Scott’s record by 430 miles. As precise as their final latitude sounds, Shackleton calculated it by dead reckoning. By this point, the party had left its theodolite behind and lost its sledgemeter. All four men swore by it, however, and few besides an embittered Markham openly doubted their word. “While the Union Jack blew out stiffly in the icy gale that cut us to the bone, we looked south with our powerful glasses, but could see nothing but the dead white snow plain. There was no break in the plateau as it extended towards the Pole, and we feel sure that the goal we have failed to reach lies on this plain,” Shackleton declared. “Whatever regrets may be, we have done our best.” He later said to his wife, “A live donkey is better than a dead lion, isn’t it?” She replied, “Yes, darling, as far as I am concerned.”52

Racing from depot to depot with no margin for error, the Polar Party made the seven hundred miles back to base in seven weeks with a story of perseverance in adversity that matched the tale of Scott’s Farthest South. “And no man told a story better,” one editor said of Shackleton, who had advance contracts for his narrative with newspaper, magazine, and book publishers.53 Largely written on the voyage home with the aid of a New Zealand journalist and featuring a balance of geographical discovery and daring adventure, wired accounts from Shackleton began appearing even before the explorer reached London. Press reports proclaimed him the “lion” of the season despite his failure to reach the pole.54 He was knighted by the king and, like only Stanley, Nansen, and Scott before him, was received by the RGS at the Royal Albert Hall, where for the first time motion pictures taken on an expedition illustrated the lecture. To mark the occasion, the society issued a new Antarctic map incorporating the expedition’s geographical survey and showing landmarks that Shackleton named for such RGS officials as Goldie, Mill, Keltie, and Leonard Darwin. Even if no one had yet reached the pole, the Polar Party had resolved its geography. The RGS map showed that there were no fixed features on the vast East Antarctic ice sheet—only a spot yet to be reached.

While in the Antarctic, the Nimrod expedition completed two more notable bits of geographical research. During the Northern Sledge Journey across the Ross Sea ice from Cape Royds toward the South Magnetic Pole, Douglas Mawson used triangulation and traverses to survey the Victoria Land coast and mountains with a precision not previously matched from ships. His findings appeared on the new RGS map. Finally, on leaving the Ross Sea, Nimrod steamed west along the Antarctica coast to a point somewhat farther than earlier expeditions. “On the morning of March 8,” Shackleton noted, “we saw, beyond Cape North, a new coast-line extending first to the southwards and then to the west for a distance of over forty-five miles. We took angles and bearings. . . . We would all have been glad of an opportunity to explore the coast thoroughly, but it was out of the question; the ice was getting thicker all the time, and it was becoming imperative that we should escape to clear water without further delay.”55 Faulty sightings by an 1838–42 American navy expedition commanded by Charles Wilkes suggested that this shoreline turned sharply northwest. Reports from the Nimrod all but erased the old Wilkes Land coast from new charts. Further evidence on this and other points of Antarctic geography would have to wait for Scott’s return.

In the society’s 1874 obituary for David Livingstone, which credited the explorer with opening “nearly one million square miles of new country, equal to one-fourth the area of Europe,” RGS President Bartle Frere commented, “It will be long ere any one man will be able to open so large an extent of unknown land.”56 Of course, that land was fully inhabited, and Livingstone opened it to Western geography with local help. As Markham and others had by then begun to stress, two much vaster areas remained virtually unknown to all humans: the deep-sea floor and Antarctica. By tracking the Transantarctic Mountains and crossing to the Polar Plateau, Discovery’s Western Sledge Journeys and Nimrod’s thrusts toward the magnetic and geographical poles opened over three million square miles of East Antarctica. Yet the deep sea had come first. In an epic 1872–76 voyage that served as a model for the Discovery expedition, naturalists aboard HMS Challenger opened the oceans to scientific study. By revealing the impact of the Antarctic on marine biology and the global climate, the Challenger naturalists helped to launch the heroic age of Antarctic science.

Map tracing the first ascent of Mount Erebus (1908), from Ernest Shackleton’s Heart of the Antarctic (Philadelphia, 1909).