On Friday, 1 February 2009, Tulio Lizcano, a Colombian congressman, escaped from FARC (Revolutionary Armed Forces of Colombia) guerrillas after eight years of captivity somewhere in the jungles of Colombia. During those eight years he talked to only seventeen people. He saw the sun only twice. And he engaged in an activity that saved his life. As he explains to the Mexican newspaper Reforma:

I found a strategy to defeat loneliness. I cut several sticks, buried them in the ground, cut little pieces of paper, and wrote some names on them of students I used to teach in the university. I placed one name on every single stick. In the morning I would prepare class with the notebook and a pencil they had given me. During the evening, just as I had done my whole life, I taught in that imaginary classroom. I asked them questions and answered in their names. That exercise, as crazy as it sounds, kept me alive.1

Lizcano constructed an imaginary relationship with students and managed to address and be addressed by them. Loneliness, strict surveillance, and confinement were tamed by the creation of intimacy in a simulated atmosphere. Lizcano was whole and sane when he reached home.

This chapter focuses on pedagogical activities that foster intimacy (that is, attachment, communication, intersubjectivity) in imprisoned spaces. I focus in particular on the creation of a mural inside Santa Marta Acatitla, the most important women’s prison in Mexico City. What I examine is a project that introduced color and textuality inside a prison through the design of a mural on the surface of the spiral stairs used only by visitors or by women prisoners in the process of their liberation. Two central questions emerge in relation to this project: What kind of “text” can emerge under intense surveillance? And how do captive spaces enable or resist signification?

THE BEGINNING

In October 2008 I was invited to join a project related to designing and painting the prison mural. Santa Martha Acatitla is a relatively new prison, opened in 2003. It is located in the eastern section of Mexico City, an unstable social and geographical space near one of the city’s biggest garbage dumps. It is a site of relatively innovative programming, a place where prison directors are proud to offer a range of educational, recreational, and artistic activities. At the same time, Santa Martha Acatitla is far from a model institution: the rooms are small and overcrowded, the food quality is very poor, and it is dirty and punitive. Inmates there have experienced a steady erosion of both health and educational conditions. Many of the internees allude, as well, to the very conservative gender roles implicit in many of the scheduled activities—for instance, knitting, cleaning, and maquila (sweatshop) work. It is as if prison rehabilitation involves their “rehabilitation” to a diminished idea of women.

Vision within this detention center is tightly controlled. The prison panopticon (watch tower) allows full visibility only for the gatekeepers. Internees cannot see freely: there are walls and bars everywhere. Some of the more progressive cultural programming nonetheless has proven disruptive, and after a workshop on photography, a group of imprisoned women were unwilling to give up the privilege of vision. They wanted to continue with the experience of creating portraits, images, and thresholds of visibility inside the prison.2 The inmates themselves came up with a new idea involving vision and unexpected frames of narration. It was a very surprising one: “We want to paint a mural in the spiral stairs.”3

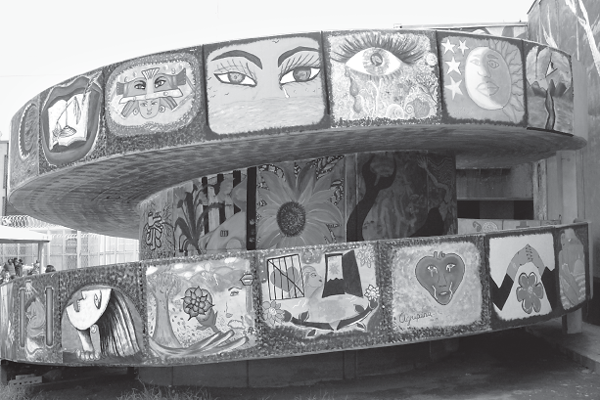

The staircase they selected was located at the southern limit of the big patio. This patio is one of the few cherished spaces inside the prison, where incarcerated women can rest and wait for their visitors, family, friends, and lovers (figure 12.1). The staircase itself contains the most anticipated or feared moment: the visit.4 It is a prohibited space for the internees, since it connects with the outside world; they can access it only when they are in the process of being released from prison.

12.1 Staircase (caracol)

Spirals are defined by their circling curving motion around a vacuum, a motion of ascent and descent. Two very important movements happen in the space of this particular spiral: family, friends, and loved ones descend to visit them, and the prisoners ascend the stairs to be released. The spiral represents the space of freedom, the connection with happiness and love to be found outside, but also pain and worry. What sort of educational enterprise were we facing when the women spoke of their desire to paint these stairs?

I was invited to work with a group of seventy inmates on a collective visual story that would ascend and descend on the spiral of these stairs. As Lauren Berlant states:

Rethinking intimacy calls out not only for redescription but transformation of analysis of the rhetorical and material conditions that enable hegemonic fantasies to thrive in the minds and the bodies of subjects while, at the same time, attachments are developing that might redirect the different routes taken by history and biography. To rethink intimacy is to appraise how we have been and how we live and how we might imagine lives that make more sense than the ones so many are living.5

Finding routes to imagine “life that makes more sense” could be a definition of what we searched for through the spiral and its curvy walls.

We planned a series of mural workshops inside a very stark classroom, with the goal of constructing a “monumental portrait,” a narration that could signify, like a portable album, a walking memory that captured women’s experience inside the prison:6 their vision and voice inside the prison. This unusual construction could flesh out eccentric and silenced impressions and intervene in the creation of a collective visual story of captivity. Our aim was not only to spell out and articulate the remains and fragments of selves that lay inside, but to magnify them, to paint them on a wall, to turn them into a monumental story of women’s lives inside prison.

Several questions soon became apparent. How could we construct a collective and monumental visual story that could represent the women’s most fragile and minuscule zones of memory and intimacy? What kinds of transitions could take us from the “inside” to the outside regarding their stories and ideas of justice? Reading and writing inside prison are intensively regulated practices. Books in the library are scarce or unavailable, and documents like the national constitution or the manual on principles and laws that regulate the prison are prohibited.7 It is very difficult to get notebooks, and paper is expensive and scarce. In this context of silencing, anything that women read and write is meaningful, especially when it is related to their intimacy or to justice.8

MURALISM: TO LOOK WITH ONE’S LEGS

Muralism in Mexico can be seen more generally as the monumental narration of hegemonic stories that signify heroism and patriotic love for the new postrevolutionary country. Made popular by Diego Rivera, José Clemente Orozco, and David Alfaro Siqueiros, among others, muralism multiplied after the Mexican revolution (1910–1921). In the United States there are also many important murals in schools, hospitals, and public buildings, painted by these and other artists as a means to revitalize American culture during the Great Depression. More recently, Chicano artists have appropriated muralism to depict their own history in their own way, to make sense of the nation, oppression, and meaning of being a Chicano/Chicana inside the United States.9 This expansive use of murals reflects the fact that they are one of the best forms of both art and education for the masses. And although the contexts and meanings of murals vary, two functions endure: educating and giving pleasure.

When the great muralist Siqueiros was asked about the way in which one should look at murals, with what knowledge and with what gaze, he answered: “Murals need to be looked at with one’s legs.”10 If we understand murals as a journey in signification, as ambulant meaning, or as stories “in transit,” what kind of possibilities does this “motion” offer to represent intimacy within the context of the prison, where there exist so many prohibitions? The process that translated inner images, thoughts, and ideas around justice took us “inside” in two different ways: inside the prison and inside women’s experiences and emotions.11

THE PEDAGOGY OF THE SPIRAL: INTERRELATION OF THEORIES, CONCEPTS, AND POLITICS

When deciding which feminist concepts and methods would travel effectively inside the prison and into women’s intimate stories, to enable them to recount and narrate from their bodies and spaces and to visually reflect on their stories inside and “outside” the prison, three articles came quickly to mind: Gail Rubin’s “Thinking Sex,” Gloria Anzaldúa’s “La Prieta,” and Joan Scott’s “Gender: A Useful Category for Historical Analysis.”12 I introduced some of the main ideas from these articles to the women in the workshop organized to figure out how “to attack the wall.”13

This triangle of essays disrupts hegemonic notions of sexual identity and es-sentialist notions of seeing and knowing, as well as assumptions about experience as transparent and unquestioned. The essays convey particular notions of social justice, explore the instability of subjectivity, and provide strong critiques of heteronormativity, whiteness as the paradigmatic authority, and the essentialization of experience. “La Prieta” can be read as a diary, as a testimony of the importance of articulating sexuality and race, and of exposing the dynamics of exclusion and the obstacles for sharing what is happening inside oneself. Intimacy may be read as a path to consciousness, to the articulation of memories, to experiencing a sense of self that is necessarily fragmented and contradictory. The articles provided a three-way axis of critique against heteronormativity, whiteness, and experience as transparent; this axis was vital to creating a frame of intelligibility in which the women in prison could unravel their stories. Most of them are prietas (women of color), as Gloria Anzaldúa would say. Many of them identify themselves as “queer”14; although they do not label themselves sexually, their stories point to the practice of an unstable and undefined form of love, which indirectly points to a feminist retheorization of control and coercion in the construction of a heterosexual body.15

These articles and their visions helped us to identify the queerness of the wall we were about to paint. We wanted to emphasize that the construction of meaning is always inserted in some sort of captivity, that any intimate content, in order to be expressed, demands the twisting, the contortion, the curling, and rolling of language to be immersed in the grammar of signification. A wall twisted and enrolled like a spiral is the best paper, the best material to imprint and entwine dislocated and eccentric visual stories emerging from inside. The staircase as a material object curves and bends, creating the contortions needed for expression in captivity. In such a way the staircase constituted a kind of Moebius band, in which inside and outside meet and collide. Such a border allows for representation of what may emerge only at the limit of speech, signification, and language. The spiral as an oblique form and as a nonlinear process of ascent and descent, a twisted and contorted wall, could be an image of a “queer” space. The classroom we created thus offered a queer pedagogy. Its queerness may be an effect of the particular space we wanted to “attack” with form and color, and the notions we had to develop to create a nonlinear narrative to match both the spiral and the profound and oblique memories inside. The curved nature of our project, of our “twisted” classroom, called for a methodology that resembled the oblique lines and curved contours of the spiral as an inaccessible space. We, the working group, had to come up with arguments to convince authorities to allow women to occupy that space while painting it.

We also needed to look beyond these three American and/or Chicana theorists, because in the Mexican context the problematization of the concept of women has emanated from beyond queer academia or Western feminism, or lesbian theorization. Equally important for any kind of liberation are Latin-American rebellions and social movements, especially the ones enacted by the prietos (that is, nonwhites, the same color as the women imprisoned, who are mostly brown). These movements are very critical of the Mexican State, and especially of its relation to the democratic notion of “justice for all.”

These social movements were particularly apt for our purposes because a number have incorporated murals as a pedagogical and political tool. One of the most visible uses of murals to narrate and spread out their “enclosed” history occurs within the Zapatistas movement. They have organized a rebellion that is still educating the rest of the nation, and they are using muralism as a pedagogic and political surface to illustrate what is going on in their autonomous territories, besieged by the military, in Chiapas. In symbolic synchronicity with their enclosed territories, we have named our mural Caracoles (“Spirals”), the same name the Zapatistas gave to their territories in August 2003.

To further grasp the political dimension of Santa Marta Acatitla’s mural, it is necessary to understand the term “spirals” (caracoles), inspired by the Zapatista and Mayan aesthetic and political worlds. The spiral has a deep meaning in indigenous culture, especially in the Mayan one. Spirals for Mayan culture represent the reordering of the world. Through centripetal and centrifugal movements, the motion of the universe functions in ascending and descending patterns.16 The ancient Mayan spiral and its property of condensing and producing new orders of signification have been resignified by the Zapatistas.17 In 2003 they transformed their territory into five autonomous regions that they renamed as caracoles. Inside them they govern themselves through the Juntas de Buen Gobierno (“Councils for Good Governance”).18 These regions are besieged and constantly harassed by paramilitary, military, and other indigenous and mestizo groups acting in compliance with the local government. In a sense, los caracoles resemble an imprisoned space, due to the high surveillance and constricted movement experienced in those territories.

These five autonomous regions, these “spirals,” are saturated with murals—today more than eight thousand murals.19 These murals preserve the traditional functions of educating and providing pleasure, but one of their other aspects is really revolutionary: the place that women occupy inside this visual narration. Very soon after the uprising, on 1 January 1994, the Zapatistas had to recognize the powerful role of women inside their movement. They began to represent their leaders on the walls in their autonomous regions, and since murals are visual artifacts that provide stories that teach the relevance of historical moments or heroic personalities, they introduced women within them. In Oventik, one of the five autonomous territories constructed by the Zapatistas, there is a strong gender perspective in the design of murals: Comandante Ramona appears on the wall beside Che Guevara and one of the most important revolutionary heroes, Emiliano Zapata. Comandante Ramona was one of the female top military officers and educators who not only won a strategic battle against the forces of the state during the 1994 uprising but provided gender leadership inside and outside the Zapatista movement.20

The contribution of Zapatista rhetoric and discourse has reconfigured the memory, subjectivity, and intimacy of the excluded (for example, Indians, women, groups in poverty) in Mexico. The Zapatistas have created a revolution in the ways of “seeing” these others that is strongly attached to their pedagogic and artistic work on murals. Since their rebellion erupted in January 199421 (just when the NAFTA accords were inaugurated), the Zapatistas’ re-narration of the nation in the surface of murals has been deep and unforgettable. Diverse evidence of their rebellion has been written on walls everywhere inside the Zapatistas territory, and also globally.

One event related to murals is especially important to grasp in order to understand the incorporation of the Zapatistas’ narratives inside the prison. In 1997 a collective mural was painted in Taniperlas, a town located within the Lacandona jungle in the Zapatistas territory of Chiapas. The day after its inauguration, the military destroyed the mural in two different ways. First, in order to silence it, they threw white paint onto the wall. Immediately after this blanking of memory, they shot it, in order to “kill” it. Hundreds of bullets penetrated the wall. After this “massacre” of colors and stories, the Zapatistas in surrounding communities gathered together and decided to reproduce the mural of Taniperlas on multiple walls. They created “walking walls,” as ambulant murals, as “stories in transit,” that would tell the story of Taniperlas all over the world. The mural of Taniperlas began to be painted at sites where oppression was increasing and where political organization and commitment to the principles defended by the Zapatista movement (equality, justice, education for all, and democracy) could be found. Their story was not only to be looked at with one’s legs, as Siqueiros would advise; it also had some legs of its own. The Taniperlas mural traveled to walls of those interested in reading one of the Zapatistas stories; they “attacked” the surfaces of schools, maquiladoras (sweatshops), and walls, not only in Mexico and the United States (such as in Tijuana and San Diego) but also in Israel and Palestine.

A special place was included in the itinerary of the traveling wall: prisons. Several prisons and detention centers on the northern and southern borders of Mexico were reached by this ambulant wall (as El Amate in Chiapas). Many migrants and political prisoners were held captive in prison at the southern and northern borders of Mexico. The borders of the Mexican nation are saturated with prisoners whose only crime is crossing them. Prisons were understood through this rebellious strategy of mural painting (as Angela Davis puts it in her book Abolition Democracy) as universities of revolutionaries.22 Revolutionaries could read their history on the prison walls and look at it with their legs, in a contained space, but within incommensurable significance.

And so, along with the consideration of the notions of experience, history, and subjectivity articulated by Rubin, Anzaldúa, and Scott, we considered the ways the Zapatistas movement has changed the way we think of alterity in Mexico, especially how Zapatista indigenous women rearticulate a discussion of nation, narration, and history in highly creative, critical, and provocative ways. The Zapatistas rebellion has been exemplary for us, especially in the use of murals as nonlinear and alternative ways to narrate the other (for example, Indian, women, the poor). The Zapatistas make clear that in order to make sense you have always to move below, to descend to make known, and to narrate portions of the national history that have been buried.23

Needing expertise in mural design and drawing direct inspiration from the Zapatistas’ spirals and murals, we contacted muralist and popular educator Gustavo Chávez Pavón (known as Guchepe), who has participated and coordinated the work on most of the murals in the Caracoles. He agreed to lend his expertise.

WORDS ON THE WALL

In order to create the mural, we needed to reflect on some of the foundations of women’s memories: their past, their present, the words and images that could transmit their emotions and their experience. To this end, we organized several workshops around three notions that would represent the depth and content of their intimate stories. The first was the notion of border as the limit that separates inside and outside, freedom and captivity, below and above, surface and interior; the second idea represented justice as the failure of a promise; the third idea was the concept of emancipation as a process of liberation constructed from inside. The conceptual tool that linked all the workshops was the notion of visual autobiography.24

During Guchepe’s (Gustavo Chávez Pavón’s) first contact with the women in Santa Martha he addressed the “intimate” face of walls. He said:

We want to transform these ugly walls for life and freedom. Art is like therapy, a way of creating intimacy between strangers, even enemies, with whom you can share your emotions. If you can’t express them, your anger grows and you end up depressed. If we can transform the walls, we can transform reality. With mural painting we develop collective consciousness through personal expression of intimate thoughts and images. Murals happen like this: I come to the wall and it tells me what to paint. If you can transform a wall, you can transform your time in jail.

When asked if it was necessary to know how to paint, Guchepe answered that the idea of not knowing how to paint is a stereotype: “Of course we need a balance in the design and sometimes help to figure out an idea in visual terms, but anybody can paint. We are composers of our own emotions, and we want designs to be real, as real as the murals painted in the Zapatistas’ captive zones.” The goal was to leave traces of what it meant to cross the border from the exterior to the interior and the reverse, to be failed by justice, and to try to free ourselves from injustice and mental captivity by painting.

One of the most radical interventions came when we were negotiating with the director of the detention center to get official permission for women to step into this inaccessible space—the stairs—in order to paint. The spiral stairs were accessible only to women prisoners in the process of liberation or to visitors from the outside. The director established on our first approach that women could only paint “one by one.” This meant that the stair could not be “appropriated” by the collectivity of women, and the process would resemble more a single silent intervention instead of a collective and scandalous one. The director granted the group access to the spiral only when we convinced her that painting a mural in collectivity in such a repressed space would convey a message of concern and interest, not only in women who were being kept locked up, but in finding and expressing artistically what women have “inside.”

Gustavo Pavón explained the kind of method that would be necessary to allow the emergence of the collective visual story that could ascend and descend in spirals:

We cannot paint one by one since our pedagogy is one of contagion. We paint with the other, within a collectivity who share thoughts, designs and colors. The only way to bring out what these women have inside is through a party, an explosion of contact and joy by the presence of colors, emotions and images. Our design, our mural, may only emerge from inside a collectivity.

The pedagogy of the spiral, the possibility of signifying enclosed experiences, can be constructed only by contagion, by silence immersed in scandalous scenarios, by infection of intimacy. Murals help us to coincide and reconcile. As our muralist said: “We may pump up balloons and free them with our thoughts written on them, like tiny surfaces that elevate and free our thoughts.”

I was deeply touched and “elevated” by his words, but I rapidly landed again in our constrained reality when one of the most articulate and smart women in the workshop said: “Yes, of course, the only thing is that balloons are prohibited inside.” Comments like that made me realize constantly the sort of walls we were painting on and within, and the importance of both defying such barriers and descending into the world of women.

Gustavo Chávez drew inspiration from and has himself painted murals around the world. In Palestine, for example, inside the wall that defines the occupied territories, he and his colleagues painted very quickly. As he put it, the will to stay alive made them work rapidly. They wore a mask in Palestine as a symbol of resistance and rebellion. Guchepe spoke of taking the Zapatistas’ mask to Palestine as a symbol of liberation, of a process of constructing autonomy based on the pure spirit of rebellion and of acting without permission. There they painted hummingbirds and upside-down eagles (the eagle is the symbol of the Mexican nation) as signs of freedom and as symbols of being in a nation upside-down. There is always a way to leave traces.

DESCENT

After our workshop, as we were about to begin to paint, I condensed one of the most transversal and common origins of the inmates’ presence as women in prison: men. During the search for the construction of the visual narrative, I heard many stories, narrations, and accounts of a triangle of betrayals: men, justice, and family. Men were the principal actors in the crimes that the female inmates had committed. Some of the women were in jail without being directly related to the crime at all; others were indirectly involved, mainly in minor acts of drug trafficking. Others did commit a crime but not the one they were charged with, and most were simply waiting to be sentenced.

Female inmates are much less visited than men; family members do not want to face the reality and the “shame” of women in prison. If the inmates have children, family members tend not to bring them to visit their mothers. The state’s provision of “justice” is the biggest wound, the deepest failure, the greatest betrayer. Women’s narratives had a common point of juncture or departure: the way in which men and justice exercised power over them, and the way women submitted. The mural was a space where they could rework and act upon this set of contradictions, where they could examine deeper motivations for their conduct.

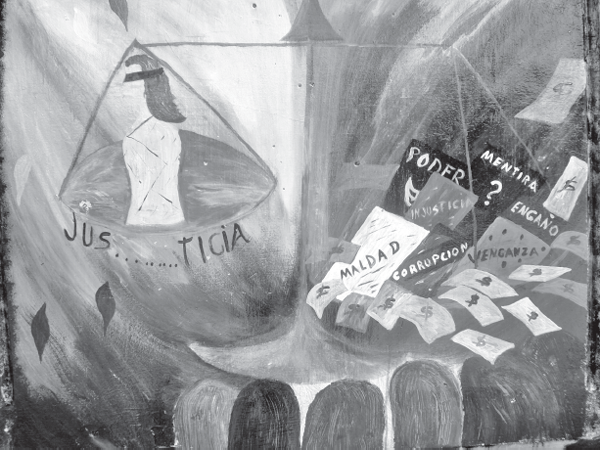

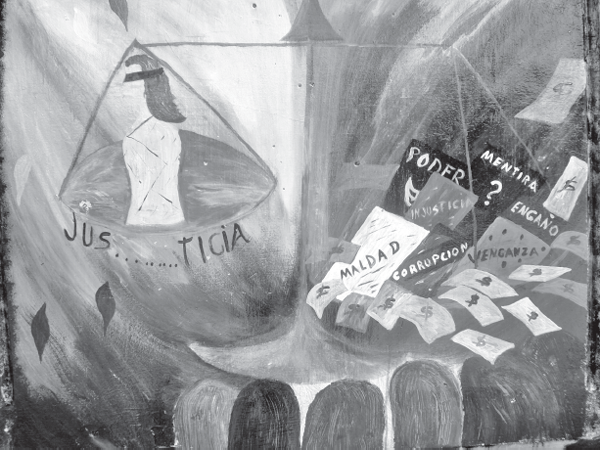

The set of workshops was organized around the notions of ascent and descent, interior and exterior, of the spiral. We worked for ten sessions. Through our work on the images and the text, I began to gather information about portions of the history of the women. I learned, for example, that Cristal was reported to the police by her husband (she was a drug addict and used to have phone sex with strangers). She is a very beautiful woman, extremely smart, provocative, and rich. “I am not a saint. I took a lot of drugs, had sex phone, and risked my life many times, but I did not commit the crime they are accusing me of. My husband told the police I participated in a kidnapping. There is no evidence at all.” Cristal developed an image in her section of the mural that concentrates on her desire for sexual arousal, her resistance to authority, and her anger and desire for men. She worked on a figure that represents the dimension of justice in her experience (figure 12.2). She came up with the idea of revisiting Greek mythology and composing Justice as a beautifully classic woman, lost, blind, and overtaken by the powers of money, sex, and seduction. Her design is similar to the one Orozco painted in the building of our Supreme Court in the center of Mexico City.

12.2 Justice

CENTRIPETAL AND CENTRIFUGAL MOVEMENTS: CONSTRUCTING THE MURAL

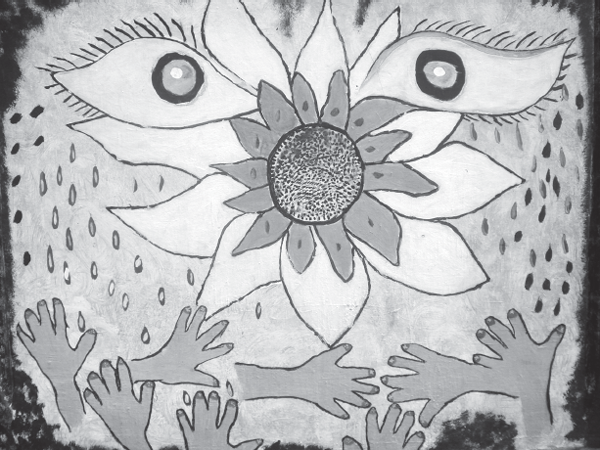

Our spiral stair is composed of 115 square cement portions of one square meter each. Between 120 and 140 inmates participated in the mural design. Women in Santa Martha organized around the painting of the stairs and “took over” portions of its surface. Sometimes more than one woman gathered to negotiate an image within a cement square. One of the first examples of collective painting was the section done by indigenous women. Indian women are mostly in jail due to failed juridical processes. Most of the so-called legal process is illegal because of the state’s failure to provide translation services.25 Three indigenous women gathered to paint their “take” on justice. One of them, Lupita, has been sentenced to sixty years for a crime committed by her brother, who was visiting her family when the police captured him.26 The women painted a flower, a sunflower, but with eyes that cried sixty tears, one for every year of Lupita’s sentence, sixty ways to see the world as a flower, a sunflower. Doña Lupita added hands to the frame to represent the support she has been given inside prison by her inmate friends (figure 12.3).

The spiral stairs had several surfaces: the exterior one; the interior one; the base, shaped as the log of a wide tree (a tropical Mayan tree called the ceiba); and the summit, a huge circle facing the sky. The interior section of the spiral functioned as a Moebius band along the surface of which two very interesting images were painted. The first one was a dark fluid that streamed down the stairs to the level of the ground, a thin river of darkness, which mixed dirt and sorrow, as if the pain of the images painted above had melted inside.

12.3 Sunflowers (girasoles)

12.4 River of darkness

The second image emphasized the notion of time inside space. As one begins to ascend through the spiral, it is possible to see on the walls pre-Hispanic symbols representing time periods in the Nahuatl cosmovision (figure 12.4). Time measured in years ascends inside the stairs.

ASCENSION: JUSTICE

Emancipation through the oblique work on the limit of the inside and the outside has taken diverse and multiplying forms. More than ten women involved in the spiral have “walked free”; two women have begun to study law; one sent her design to a contest and won second place; others have limited family pressures and demands.27

We finished the mural in September 2009. Today we are expanding the spiral to other sections of the center. The news is spreading inside the prison that women who paint “walk free.” Some walk free to the outside; others engage in a journey to the center of their very being, a walk inward.

The tendency of the spiral to reorder signification seems to grow and incorporate other spaces inside and outside prison. Today we are preparing another mural inside Santa Martha. I want to conclude with one image that proves the outreaching power of the spiral.

One of the most intense discussions inside our workshop was about borders. We came to the conclusion that a story can be developed only by making visible the trespassing of limits and borders: a crossing.28 The mural text, our visual narration, performs an effect of crossing. The mural had to address a number of borders, of limits, trespassed by women: from being single to getting married, from textual to visual, the border of maternity, the line crossed when you commit a crime, from intimacy to monumentality, or when you allow yourself passively to be a victim. But the border that created the most emotion was the one that separates the United States from Mexico. Many women had family members in the United States or had lived there themselves. One of the women had a brother in the U.S. Army in Iraq, based in Samarra, and she told us that a similar spiral was created there hundreds of years ago. It is a minaret constructed during the ninth century, a huge ascending construction created to call for prayers, a spiral that needs to be looked at with one’s legs. The same women told us, “When you go to the United States, let them know that we are painting this spiral of liberty.”29 We also discussed what was happening in Abu Ghraib prison and considered the power of mural painting as a way to gain consciousness.30

The act of gathering photos to document our work made me understand the logic of images inside prison. Women in prison are very cautious about being photographed. During the workshops the fear and distrust of being photographed was displaced, and instead they gave in to the visual urgency to depict what hurts: to kneel down before the borders we have to cross, to represent pain and hope, to construct a visual notion of justice.31 I was eager to move them to recognize what happens when you witness your own experience transformed into visual terms. The Abu Ghraib photographic recording of atrocities constituted an extraordinary pedagogical moment to help them “see” what images “do”: help to perceive the event, the experience, as really happening.

Reactions to the Abu Ghraib photographs change when viewed from within a prison. There is some understanding of the one who took some of the photographs that anatomize shame inside the prison. To look inside Sabrina Harman’s emotions, to recognize her need to visually register what was happening in order to believe it, reveals the role of intimacy as a window and opportunity to develop another story.

The knowledge of a deeper and more complex story behind the images became visible when we learned about the testimony of the female soldier who recorded acts of violence. Sabrina Harman received a court notice to open her letters to the public, letters in which she stated to her girlfriend what was going on in Abu Ghraib. The letters showed that recording was a way for her to believe what she was seeing. To look through the lens and produce a photograph helped in this case, not to misrepresent through the allure of photography, but to make it real.

What sort of visual stories could the internees in Abu Ghraib or in other American prisons such as Guantanamo narrate, if we were to provide an oblique classroom and some walls? Watching the documentary Standard Operating Procedure, we could hear soldiers, generals, and officers, but not the prisoners.32 The walls of Abu Ghraib remain gray and empty. They have to be painted and filled with the stories that need to be told to initiate the ascendant and descendent move of the spiral, which creates the foundations of a new narration of what America is or may become.33

I have written about the experiences of women and their spirals in one prison in Mexico City to let you know about their intimate emotions, desires, and concerns about justice as women, as rebels, as the weakest link of men, but also as partial owners of their stories and their lives. Women’s spirals from Santa Martha reach out in curving motions to Samarra, or to any other end of the world where there is silence that could speak, as long as anybody could imagine an impossible pedagogical scene, be it a workshop where imprisoned women can access the inaccessible and represent the unrepresentable or a jungle where an imprisoned man keeps sane by imaging a classroom—anywhere we may twist walls and create spiral streams of color in ascending and descending patterns (figure 12.5), motions of intimacy that may save our lives.

12.5 Mural

NOTES

I thank Claudia de Anda and Antonio Cintora for the invitation to paint a mural inside Santa Marta Acatitla, a female prison in Mexico City. Without them this project would not have been possible. I especially thank Gerardo Mejía for his collaboration, not only during the project but later in capturing and organizing images and preparing the text. Special thanks also to Arelhí Galicia, who managed to organize access and obtain permissions inside the center, both unimaginable activities when we witnessed the surveillance inside the prison. Irais García and Mariana Gómez organized access and tools as well as the interviews we conducted with the internees after we completed the mural. Though I was the coordinator for the event, most of the decisions around the project were taken as a group. When I use “we” I mean the participation of this group.

1. See Reforma, 15 February 2009 (author’s translation).

2. To learn more about women in Santa Martha, see Humberto Padgett, Historias Mexicanas de mujeres asesinas.

3. Translator’s note: Escalera de caracol may be translated as “spiral stairs” or “spiral staircase.”

4. Women in prison are abandoned by their spouses, lovers, and family in a much higher percentage than are men. Thus the visit may be an extraordinary and very much anticipated event.

5. Laurent Berlant, Intimacy, 6.

6. A section of the methodology to create the mural, the one related to gender pedagogy, has been developed by Patricia Piñones, a professor of Women Studies at UNAM (National Autonomous University of Mexico) working at the Women Studies Program that I chair.

7. One of the interns asked us for a constitution. She was studying her rights and readdressing her case. To provide this, we stuck an image of a comic book (Bird Women) on the cover and turned the national constitution into a comic book. With such a cover, the constitution could pass into the prison and the hands of this woman.

8. More than 70 percent of the female interns are imprisoned for insignificant crimes involving thefts of less than $100 U.S. This is due to a juridical reform made in Mexico City in 2002 that increased the price of bail and made it impossible for critically poor women to make bail, even for a petty crime such as stealing a fish in a market. Only a small percentage of inmates are imprisoned because of a real crime. More than half of the crimes processed are related to a man in the family (spouse, boyfriend, father, uncle, brother, brother-in-law). The women imprisoned by the crimes of their men are called pagadoras (payers). This means they are doing time instead or because of their men, since they are regularly involved with marginal or minor sections of the crime they are accused of committing. See Elena Azaola, “De mal en peor.”

9. See Heather Becker, Art for the People.

11. We found, though, that in the process of developing the mural, authorities were either lazy about interpreting our criticism of the wall or they allowed portions of truth to be obliquely written. Nobody controlled what we painted on the wall.

12. Gayle Rubin, “Thinking Sex”; Gloria Anzaldúa, “La prieta”; Joan Scott, “Gender.” The essays are quite theoretical, with the exception of Anzaldua’s “La prieta,” (which is easy reading and could be used as an example of autobiography). On “Thinking Sex,” I encouraged the women to think of what it meant to be sexually controlled by the state (their sexuality is obsessively surveilled). Scott’s essay enabled them to focus on their intimate history located at the border of reality and fiction. In other words, it offered the possibility to conceive the “truth” of their visual designs as an effect of narration and fiction, not necessarily of “real” factors. These essays also address race, sexuality, and gender as key for transformation; women in prison are also enclosed within these axes of identity.

13. “Attack” was the verb used by one of the internees, since walls are the objects that keep them away from the outside; to paint them was to rebel strongly against their function of containment.

14. In Mexico the notion of “queerness” or “queer” has traveled unevenly. Intellectuals like Norma Mogrovejo have worked with it, critiquing its dubious use for politics. (See Mogrovejo, Un amor que se atrevió a decir su nombre.) We use it here, as Butler and others point out, considering the oblique possibilities related to desire, writing, and subjectivity. What I want to stress here is the necessary “twist,” the nonlinear methodology of such a notion, the spiral effect when we deal with sexuality in any space, but especially inside prison.

15. Sex between women in prison is common, since the normativity for sexual intimacy with men is very strict and frankly misogynist. Women in prison frequently are abandoned by their families. To be able to enjoy an intimate visit, they have to prove that they are in a stable relationship with a visitor. This is very hard to demonstrate since they do not have the possibility—while imprisoned—to engage in new relations. In short, what we face is the manufacture of celibacy and the proliferation, in some cases forced, of queer and lesbian sexual relations inside prison. Notwithstanding this qualification, some women report that the best sex and the most profound love they have experienced has been with women in prison. See Marisa Belausteguigoitia, “Mujeres en espiral.”

16. See Miguel León-Portilla, Los antiguos Mexicanos a través de sus crónicas y cantares.

17. The Zapatistas rebellion erupted on 1 January 1994. From 1994 to 1996, the rebels negotiated with the government precise changes in the constitution in order to be granted cultural and political autonomy. In 2001 Congress voted against this “contract.” Today the Zapatistas do not accept economic support from the government and govern their regions autonomously with strong surveillance and intervention by the military, paramilitary, and disguised government actors, hidden behind NGOs like OPDDIC (Organización para la Defensa de los Derechos Indígenas y Campesinos A.C./Organization for the Defense of Indigenous and Peasants’ Rights).

18. The five designated regions known as caracoles (spirals) are: La Realidad, Oventic, La Garrucha, Roberto Barrios, and Morelia. Today they are particularly harassed; Morelia has been attacked by official organizations such as OPDDIC.

19. For more on muralitos zapatistas, see Luis Adrian Vargas, El muralismo Zapatista en Oventic.

20. See Márgara Millán, “Las Zapatistas del fin del milenio.”

21. In Mexico, for decades murals have been a paradigmatic resource to narrate monumental episodes of our national history. The Zapatista movement has constantly reappropriated segments of the nation’s history through the construction of alternative narrations that have made visible the unrecorded experiences of Indians and, today, of women. To see more on the uses of murals inside Mexican history, see Vargas, El muralismo.

22. See Angela Davis, Abolition Democracy, 7.

23. At the beginning of the rebellion, Subcomandante Marcos communicated with a distinctive strategy. He attached postscripts to his communiqués in order to insert different levels of communication from below. Soon the postscripts began to multiply to the point of creating a wide list in one communiqué. For more on these strategies of descent, see Marisa Belausteguigoitia, “Máscaras y postdatas.”

24. For more on the notion of visual autobiography, see Anna Marie Guasch, Autobiografías visuales.

25. In Mexico we find more than 60 ethnic languages; more than 50 percent of indigenous women do not speak Spanish.

26. Commenting on the types of offenses committed by indigenous women is very complex. Access to their cases is very difficult and granted only to their lawyers. We rely on the stories the prisoners have told us. Their own accounts, complemented by the literature around the perverse justice system in Mexico, establish that most offenses were related to men dealing with drugs. Women are the “weakest link,” often simply wrongly accused of crimes due to failed translations; most Indian women do not speak Spanish fluently, and although translation is legally required it frequently is not provided by the state (see Azaola, “De mal en peor”).

27. We have not yet done the necessary research to know the reason for this number of women “walking free.” Of course, painting is not one of them, but the image of them ascending to freedom was a very powerful one for the conception of the phrase “the one who paints walks out.”

28. According to Ricardo Piglia, a story is the result of the crossing of a special border, the one that lies between a secret and its unveiling: Ricardo Piglia, Formas breves.

29. Gloria Anzaldúa gives an account of the complexity of stories emanating from the border between the United States and Mexico, where an enormous wall is being both erected and appropriated by painting: Gloria Anzaldúa, Borderlands/La Frontera).

30. Mark Padilla et al. warn us, however, that local accounts of intimacy should not be blind to the ways in which globalization permeates these affective and social relations: Mark Padilla et al., Love and Globalization.

31. Virginia Woolf, in Three Guineas, and later Susan Sontag, in Regarding the Pain of Others, explore the powerful effect that images may have on the cause “to end the war.” Both writers analyze the power of photographs—of images—to reveal and mislead.

32. Standard Operating Procedure is a 2008 documentary film, directed by Errol Morris, that explores the meaning of the photographs taken by the police and army at the Abu Ghraib prison.

33. In Madrid, popular educators conducted a project whose goal was to paint the walls of Carabanchel, a prison for Spanish Republicans (leftists) during the Spanish Civil War and afterward. One night in November 2007, police came with bulldozers and destroyed Carabanchel. The practice of painting the walls of prisons is becoming more and more popular. See http://salvemoscarabanchel.blogspot.com/.

BIBLIOGRAPHY

Anzaldúa, Gloria. “La prieta.” In Cherríe Moraga and Ana Castillo, eds., This Bridge Called My Back. San Francisco: ISM Press Books, 1988.

——. Borderlands/La Frontera. The New Mestiza. San Francisco: Aunt Lute Books, 1999.

Azaola, Elena. “De mal en peor: Las condiciones de vida en las cárceles Mexicanas.” Nueva Sociedad. Mexico: CIESAS, Plaza y Valdés, 2006.

Becker, Heather. Art for the People: The Rediscovery and Preservation of Progressive- and WPA-Era Murals in the Chicago Public Schools, 1904–1943. San Francisco: Chronicle Books, 2002.

Belausteguigoitia, Marisa. “Máscaras y postdatas: Estrategias femeninas en la rebelión indígena de Chiapas.” Debate Feminista, año 6, vol. 12. Mexico, 1995.

——. “Mujeres en Espiral: Justicia y cultura en espacios de reclusión.” In Experiencias en territorio: Género y gestión cultural. Mexico: PUEG, UNIFEM (forthcoming).

Berlant, Lauren. Intimacy. Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 2000.

Butler, Judith, and Joan Scott. Feminists Theorize the Political. New York: Routledge, 1992.

Davis, Angela. Abolition Democracy: Beyond Prison, Torture, and Empire. New York: Seven Stories Press, 2005.

El libro de los libros del Chilam Balam. Mexico: Fondo de Cultura Económica, 2004.

EZLN. Documentos y Comunicados. Mexico: ERA, 1994.

Guasch, Anna Maria. Autobiografías visuales. Mexico: Siruela, 2009.

León-Portilla, Miguel. Los antiguos Mexicanos a través de sus crónicas y cantares. Mexico: Fondo de Cultura Económica, 2005.

Millán, Márgara. “Las Zapatistas del fin del milenio. Hacia políticas de autorepresentación de las mujeres indígenas.” In Belausteguigoitia Marisa and Leñero Martha, eds., Fronteras y cruces: Cartografía de escenarios culturales Latinoamericanos. Mexico: PUEG/UNAM, 2005.

Mogrovejo, Norma. Un amor que se atrevió a decir su nombre: La lucha de las lesbianas y sus relaciones con los movimientos homosexuales y feminista en América Latina. Mexico: Centro de Documentación y Archivo Histórico Lésbico (CDAHL), 2000.

Padgett, Humberto. Historias Mexicanas de mujeres asesinas. Mexico: Planeta, 2008.

Padilla, Mark, Jennifer Hirsch, Miguel Muñoz-Laboy, Robert Sember, and Richard Parquer. Love and Globalization: Transformations of Intimacy in the Contemporary World. Nashville: Vanderbilt University Press, 2007.

Piglia, Ricardo. Formas breves. Buenos Aires: Temas, 1999.

Rubin, Gayle. “Thinking Sex: Notes for a Radical Theory of the Politics of Sexuality.” In Carole Vance, ed., Pleasure and Danger. London: Pandora, 1989.

Scott, Joan. “Gender: A Useful Category for Historical Analysis.” American Historical Review 91, no. 5 (December 1986): 1053–75. For the article in Spanish, see Joan Scott, “El Género como una categoría útil para el análisis histórico.” In Marta Lamas, ed., La construcción de la categoría de género. México: PUEG/UNAM, 1996.

Sontag, Susan. Regarding the Pain of Others. New York: Picador, 2004.

Vargas, Luis Adrian. El muralismo Zapatista en Oventic, Chiapas. Mexico: UNAM, 2007.

Woolf, Virginia. Three Guineas. San Diego: Harcourt Brace Jovanovich, 1966.