5 Discourse

- act structure

- adjacency pair

- back channels

- coherence

- cohesion

- cohesive ties

- discourse

- Discourse

- discourse markers

- exchange structure

- fragmentation

- genre

- idea structure

- information state

- integration

- narrative

- participation framework

- recipient design

- referent

- register

- repair

- schema

- speech act

- speech event

- speech situation

- tone units

- transcription

- turn at talk

- turn continuers

- turn transition place

- utterance

Chapter preview

Discourse is the use of language above and beyond the sentence: how people use language in texts and contexts. Discourse analysts focus on peoples’ actual utterances and try to figure out what processes make those utterances appear the way they do. Through discourse, people

- represent the world

- convey communicative intentions

- organize thoughts into communicative actions

- arrange information so it is accessible to others

- engage in actions and interactions with one another

- convey their identities and relationships

This chapter provides an overview of central concepts and methods through in-depth discussion and analyses of spoken discourse and written discourse. Models of function and coherence in spoken discourse are also presented.

Goals

The goals of this chapter are to:

- define discourse and demonstrate how to analyze spoken and written discourse

- explain the relationship between structure and function in discourse

- demonstrate how repair in discourse works

- describe the effects of recipient design

- explicate the relationship between text and context

- describe the planes of discourse and their relationships

Language use above and beyond the sentence

Almost everything that we do in our everyday lives depends on language. In fact, it is hard to even imagine what our world would be like without language. So much of what keeps people and societies together depends crucially on language. We need language to make and enforce laws; get and distribute valued resources; create and maintain personal and public relationships; teach children our ways of “being,” “thinking,” and “doing”; engage in scholarly inquiry; preserve our past and plan our future. Language allows us to make friends (and enemies), joke and argue with each other, celebrate happy occasions and mourn sad ones.

But what is there about language that lets us engage in so wide a range of activities? Certainly sounds, morphemes, lexical items, and sentences are part of the story. Sounds produce acoustic signals that combine to convey propositions that are systematically arranged into grammatical strings. But what happens then? A sound, morpheme, word, sentence, or proposition almost never occurs on its own. They are put together in discourse.

In this chapter, we learn about discourse analysis, the branch of linguistics that focuses on language use above and beyond the sentence. The terms “above” and “beyond” may sound like we’re embarking on an interstellar expedition of some kind, but they capture different features of the “discourse” mission. For most of its long scholarly tradition, linguistics perceived the sentence as the limit of the language system. Linguists focused mainly on the forms of language (sounds, morphemes, word, and sentences); how language was used in context was not explored. Speakers, hearers, and situations were outside the realm of analysis. It is by examining units larger than sentences, then, that discourse analysts go “above” the sentence. And it is by examining aspects of the world in which language is used that discourse analysts go “beyond” the sentence. At the same time, it is important to remember that real people, using language in the real world (and in the rush of real time) are analyzing discourse as well – drawing inferences about meaning from features of the discourse.

Because of its broad reach into the psychological, social, and cultural worlds, discourse analysis draws from many different disciplines and from a variety of traditions within linguistics. The construction of discourse involves several simultaneous processes. Some are the linguistic processes of arranging sentences and conveying meanings. Beyond these linguistic processes are cognitive processes that underlie the organization of thoughts into verbal form. The organization of information is influenced by discourse processes that draw on interactional roles (who is speaking? who is listening?) as well as more stable social relationships among people (for example, one’s role in a family or one’s socioeconomic status). Still other discourse processes draw upon implicit cultural models – displayed by our elders and our peers – of what we should do, how we should act, and what kinds of people we should be.

A discourse differs from a random sequence of sentences because it has coherence – it conveys meaning that is greater than the sum of its parts. It is not unusual to think of something as having its own identity beyond the identities of the smaller parts within that entity. For example, culture is more than what we do: it is a way of thinking about the world and a way of locating ourselves in that world that guides the way we act. Likewise, society is more than the sum total of the individuals who live in it. Cultures and societies are not simply the coincidental result of human instincts, individual drives and personalities. So, too, discourse is more than the addition of separate sentences to each other. Rather, there are structured relationships among the parts that result in something new and different.

Discourse is a unit of language above and beyond a mere accumulation of sounds, morphemes, words, clauses, and sentences. It is easy to think of a written discourse this way. A novel, short story, essay or poem has an identity that develops through patterned relationships among sentences, among ideas or characters, through repetition or variation of rhythm and rhyme. In the same way, when we construct and co-construct spoken discourse by talking to each other, underlying processes of speaking, thinking, acting, and interacting come together to produce an overall sense of “what is going on.”

The analysis of linguistic performance – and the social and cultural inferences it allows – raises important questions about the relation of language to other human systems. Does language form a separate system of rules, different in kind and function from other rules of human thought and behavior? If not, then to what other systems could it be related? Is language related to cognition? Is it embedded within social norms and cultural prisms? The degree to which knowledge of language is part of a more inclusive body of knowledge through which we live our daily lives is an ongoing topic of discussion in the field of linguistics. The linguistic anthropologist Dell Hymes (1974: 79) suggests that the structural (i.e. formalist) and functional approaches to analyzing language differ in a number of ways.

Most linguists who analyze discourse adopt, at least partially, a functional approach to language. This is not surprising: observing and analyzing what people do with language leads naturally to an interest in the “work” that language can do – the functions it enables people to perform.

Data: language use in everyday life

Analysis of discourse is always analysis of language use. This means that linguists studying discourse usually do not ask native speakers of a language for their intuitions about grammaticality or engage in thought experiments about meaning. Rather, discourse analysts examine actual samples of people interacting with each other (by either speaking or writing) in everyday situations. They believe that the structure of discourse can be discovered not from peoples’ intuitions about what they might, could, or would say, but primarily from analyses of what people do say. Discourse analysis focuses on the patterns in which sentences (and other units such as acts and turns) appear in the texts that are constructed as people interact with one another in social contexts.

Like other linguists, discourse analysts believe that the form of language is governed by abstract linguistic rules that are part of speakers’ competence. But added to linguistic rules are principles that guide performance, the use of language. Knowledge about discourse is part of what Hymes (1974) has called communicative competence – our tacit cultural knowledge about how to use language in different speech situations, how to interact with different people engaged together in different speech events, and how to use language to perform different acts.

We can see how our knowledge about language intersects with our knowledge about social and cultural life by taking a look at the discourse examples below, drawn from a collection of routine speech events:

| (1) |

|

We can infer a great deal about what is going on in this brief exchange from features of the interchange. Gail and Debby seem to be talking on the phone; hello with rising intonation (represented by the ?) is typical of the way Americans answer the phone. Notice that Debby doesn’t ask for Gail (for example, Hi, is Gail there?), nor does she identify herself (Hi, this is Debby). What Debby doesn’t say, then, allows us to infer that Debby and Gail know each other pretty well; Debby recognizes Gail’s voice and seems to assume that Gail will recognize hers. We can also infer (from the exclamation oh) that Gail’s presence is surprising to Debby. And the statement you’re home already, shows that Debby knows something about Gail’s intended schedule.

Snippets of discourse from our daily lives show us how much we – as “after-the-fact” analysts and as real-time language users – can infer about “what is going on” from routine uses of language. Likewise, gathering examples of routine speech acts (such as requests, compliments, apologies) and speech events (such as face-to-face greetings or telephone openings) can reveal both their similarities and their differences. However, although collecting examples of discourse from our own everyday lives is valuable, it has several limitations. First, when we hear an interesting bit of discourse and then jot it down, we usually cannot capture stretches of discourse that are longer than a few sentences or turns at talk. (A turn at talk is the period of time in which someone is granted and/or takes the opportunity to speak.) Second, it is difficult to reconstruct the nuances of speech, particularly when several people are interacting with each other. These nuances are especially helpful when we try to figure out how it is that interlocutors (people talking to one another) interpret what is going on; crucial information can reside in a pause, a sigh, a downward intonation, a simple oh or well, or the arrangement of words in a sentence (for example, I want the cake versus The cake is what I want). It is impossible to recall all of the speech that appears throughout the course of a speech event (the type of interaction that participants assume is going on) or the speech situation (the type of occasion or encounter). And because our memories are fallible, we usually fill in details based on our prior knowledge of what typically happens.

Dell Hymes (a linguistic anthropologist) developed a subfield of linguistics and anthropology called “ethnography of communication.” He persuaded linguists and anthropologists to analyze the social, cultural, and linguistic properties of three units embedded in one another:

Discourse analysts correct for the limitations of relying only upon what they hear in their everyday lives in several ways. The way that they do so depends partially upon the topic they are studying and partially upon their interest in generalizing their findings. For example, discourse analysts who are interested in how groups of people use discourse to communicate at work often do fieldwork in a workplace. There they observe activities (e.g. meetings, chats at the water cooler) and interview people who perform different tasks (e.g. managers, secretaries). They can then propose generalizations about that workplace and perhaps about other workplaces with similar characteristics.

Other discourse analysts may be interested in a particular aspect of discourse: how do people apologize to one another? When, where, and why do people use the word like (as in I’m like, “Oh no!” or It was like a crazy thing, like weird)? Then they may rely upon tape-recorded speech from a wide variety of settings and occasions, paying less attention to obtaining a sample that represents a subset of people and their activities in a particular social setting, and more attention to getting enough examples of the discourse phenomena in which they are interested. Still other discourse analysts might be interested not in the discourse of a particular setting, or one aspect of discourse, but in every aspect of only one discourse. They might delve into all the details of several minutes of a single conversation, aiming to understand how it is that two people use many different facets of language to construct a discourse that makes sense to them at that time.

Regardless of their type of inquiry, most discourse analysts rely upon audio or video-recordings of interactions between people in which speech is the main medium of communication. Once speech has been recorded, analysts have to then produce a transcript – a written version of what was said that captures numerous aspects of language use, ranging from features of speech (such as intonation, volume, and nonfluencies) to aspects of interaction (such as overlaps between turns at talk) and, if possible, aspects of nonvocal behavior (such as gaze and gesture). Transcriptions of spoken discourse look quite different than other scripts with which we might be familiar. For example, unlike most scripts for dramatic productions, linguists’ transcripts try to indicate features of speech production and interaction, often using notations like those in Box 5.2 on transcription conventions.

I always keep a tablet of paper nearby to jot down observations, questions, and ideas about what I am transcribing. Those who transcribe right on the computer can keep two files open at the same time, or just insert comments (in a different font or type size) alongside the material in the transcription file.

Transcribing a conversation is an invaluable analytic tool. It freezes moments in time and allows the discourse analyst to focus on particular aspects of the conversation. But it is important to remember that transcribing speech is, unavoidably, a selective and interpretive representation of a subset of what goes on in a conversation. For example, Elinor Ochs (1979) found that the traditional convention of ordering turns at talk one under the other misrepresented the collaborative nature of caregiver–child interactions; putting adult and child utterances in separate side-by-side columns allows the viewer to see their very different roles – e.g. how caregivers accommodate to the limitations of young children’s developing linguistic and communicative competence.

When you transcribe, you make lots of choices, depending on what questions you are asking about the data. For example, how do you want to “chunk” the stream of talk into lines of transcript? By speaker? By speaker and “T-units” (an independent clause and its dependencies) or smaller intonation units? How do you want to represent pronunciation of words (giving, givin’, [gIvIn])? How carefully do you want to time pauses? Which prosodic features (like amplitude and pitch) do you want to capture?

Discourse analysts use a variety of symbols to represent aspects of speech, including the following:

- .

-

sentence-final falling intonation

- ‘

-

clause-final intonation (“more to come”)

- !

-

exclamatory intonation

- ?

-

final rise, as in a yes/no question

- …

-

pause of 1/2 second or more

- ′

-

primary stress

- CAPS

-

emphatic stress

- [

-

overlapping speech.

- ]

-

no perceptible inter-turn pause

- :

-

elongated vowel sound

- -

-

glottal stop: sound abruptly cut off

- “ “

-

dialogue, quoted words

- ( )

-

“parenthetical” intonation: lower amplitude and pitch plus flattened intonation contour

- hhh

-

laughter (h = one second)

- =

-

at right of line indicates segment to be continued after another’s turn; at left of line indicates continuation of prior segment after another’s turn

- /?/

-

inaudible utterance

- { }

-

transcriber comment on what is said

You can see many of these symbols in the excerpts of discourse throughout this chapter.

Transcribing spoken discourse is challenging and often frustrating, not to mention time-consuming: some linguists spend close to ten hours transcribing just one hour of speech. But fortunately, what results is a transcript that they can analyze from different angles years after the original speech. The process of transcribing is also very instructive! By listening – again and again – and trying to fine tune one’s written record of what is said, linguists often end up doing preliminary analyses.

Spoken and written discourse: a first look

We create discourse by speaking or writing. These two processes rely upon language, of course, but they do so in strikingly different ways. And not surprisingly, their products achieve coherence through very different means. We can see this briefly by comparing the following excerpts from a story that Gina tells her friend Sue (in 2a) and writes (in 2b). In both excerpts, Gina introduces a story about how her love for magnolia blossoms got her into trouble when she tried to smell a blossom that then snapped off in her hand.

| (2) |

|

In both versions, Gina describes the scent of a particular flower, a magnolia blossom. In the spoken version (2a), Gina involves Sue in her description; they both use short tone units to take short turns at talk. (Tone units are segments of speech production that are bounded by changes in timing, intonation, and pitch.) Gina first asks Sue if she has ever smelled such a blossom (a sensory experience referred to by a verb). After Sue acknowledges that she has (Mmhmm), Gina presents her own assessment of their scent (Absolutely gorgeous). Because Sue agrees (Yeah), and then adds her own description (they’re great), both women have become jointly involved in the remembered pleasure of magnolia blossoms.

In Gina’s written version (2b), the intensity of the magnolia scent is not unpacked, piece by piece, across turns and short units. Rather, the fragrance is integrated into a complex sentence in which a great deal of other information is packed. Gina introduces the flower by recalling the process through which she encountered it. The fragrance appears at a specific time (On one particular morning this summer). The existence (there was) of a certain fragrance (referred to as a static thing by a noun) allows Gina to recognize the presence of a glorious magnolia. Although some of the same basic material is presented in both segments, Gina phrases and organizes the information differently.

In the following sections, we will learn more about the properties of spoken and written discourse and how to analyze both of these ways of creating discourse. We compare two transcripts to describe several different aspects of spoken discourse and explain some basic concepts and tools of analysis. We then broaden our understanding of discourse processes and structures by briefly comparing spoken discourse with samples of written discourse.

Spoken discourse

In spoken discourse, different kinds of processes – and different configurations of language – work rapidly together to produce coherence. When we speak to each other, we try to achieve several goals, sometimes all at the same time. For example, we verbalize thoughts, introduce new information, repair errors in what we say, take turns at talk, think of others, and perform acts. We achieve these goals by using and connecting a range of different units – speech acts, idea units, turns at talk, as well as sentences. Speakers anticipate what their recipients need (e.g. how much information do they need?) and want (e.g. how polite do they expect me to be?). Speakers design what they say in relation to “educated” guesses about their hearers. These guesses are based on both past experience and the current interaction.

To exemplify these points we will discuss two segments of spoken discourse from the same speech situation – a sociolinguistic research interview – in which one speaker seeks information from another about a specific topic of interest. Together the two segments will illustrate a variety of processes and structures, including question/answer sequences, lengthy repairs of unclear meanings, exchanges of short turns at talk, and maintenance of a long turn at talk in which a story is told. Also illustrated is how people jointly ease new information into a discourse and collaboratively develop topics of talk.

We begin with an excerpt from an interview that took place while Anne (a linguistics student) was driving Ceil (a local resident of Philadelphia) around the city in order to learn more about its neighborhoods. The exchange begins as Ceil and Anne enter a part of Philadelphia with an Italian market. Both Ceil and Anne like shopping at the market and Ceil describes how she and her cousin used to use public transportation (the trolley car) to go to the market.

Read the excerpt closely several times, not just to understand the content, but also to get a feeling for the rhythm of the interaction (e.g. who speaks when) and to “hear it” in your own head. You will then be more ready for the “guided readings” that a discourse analysis can provide.

Sequential and distributional analyses

Two kinds of “readings” typically are combined in discourse analyses. One “reading” focuses on the sequence of what happens: who says what and when? What is its significance at that particular point in the discourse; how is it related to what came before and what will come after? The other “reading” focuses on the distribution of specific features or qualities of language in the discourse; what forms, or ways of speaking, occur where? Do some features of language occur together more than others? If so, what could account for this co-occurrence?

Imagine that you’re interested in learning about classroom discourse. You hear a student answer a teacher’s question by prefacing it with well and you’re curious about the use of well in the classroom. How do you start your analysis? A sequential analysis focuses on the details of the specific question/answer speech event – its setting, the participants, the informational content of the question and its answer, and so on. What you would learn about well would be its specific contribution to the meanings that are emerging at that moment in the classroom. A distributional analysis would start by finding all the uses of well in the classroom and then identifying their different contexts of use, including (but not limited to) question/answer speech events. What you would learn about well would be its relationship with other features of the discourse, e.g. its use with different participants, contents of questions and answers, and so on. The two analyses together enrich our understanding of individual moments in a particular interaction and of more general discourse features and processes.

Repair and recipient design

As we noted above, Anne and Ceil are driving around Philadelphia. In (a) to (c), Ceil identifies (and praises) the section of the city that they have just entered. Anne labels the section (e), Ceil agrees with the label (f) and assesses it again. As Anne is agreeing Oh, I do, too (i), Ceil begins to explain why she likes the market in Oh:, I’d love to have one up there because- (j). Ceil and Anne continue to praise the market (in (k) through (o)), and then, as indicated by the discourse markers I mean and like, Ceil begins to explain her fondness for the market through an example. (Discourse markers are small words and phrases that indicate how what someone is about to say (often at the beginning of a spoken utterance) fits into what has already been said and into what they are about to say next.)

Repair sequences are routines in discourse which allow interlocutors to negotiate the face-threatening situation which arises when one speaker makes a mistake. Repair sequences have two components, initiation and repair, each of which can be handled by the speaker who made the mistake (self) or another participant (other). Initiation identifies the trouble source and repair fixes it. Each repair sequence communicates a different message. For example, the speaker who made the mistake can “self-initiate/self-repair,” like Nan in the example below, sending the face-saving message “I know I made a mistake but I caught it and I can fix it.”

NAN: She was givin me a:ll the people that were go:ne this yea:r I mean this quarter y’knowJAN: Yeah

If the speaker doesn’t recognize the trouble source, the other can initiate a repair but allow the speaker to make the actual repair (and prove his competence):

KEN: Is Al here today?DAN: Yeah. (2.0)ROGER: He IS? hh eh hehDAN: Well he was.

Notice that Roger waits 2 seconds before initiating the repair and then points Dan toward the trouble source (He IS?).

What is the message sent by Al’s other-initiated other-repair (below)?

KEN: He likes that waitress over there.AL: You mean waiter, don’t you? That’s a man.

Notice, however, what happens as Ceil begins to refer to those who used to accompany her to the market. Ceil self-initiates a repair by interrupting her own utterance in (s) And bring the – marking something about that utterance as a trouble source. The article the usually precedes a noun whose referent (the thing being spoken about) is definite (that is, relatively familiar or identifiable to the listener). Ceil is about to refer to some referent as if Anne knows who she’s talking about, but apparently realizes that Anne won’t know who she’s talking about without more information. Her next several utterances provide the necessary information. In (t) Ceil begins to clarify who they used to bring (like we only had-) and then realizes that she must back up even further to explain who we refers to (like Ann and I, we- my cousin, Ann?). In (v), she begins to return to her story but detours again to further identify the initial referents: We- like she had Jesse and I had my Kenny. In (x), when Ceil completes her self-repair (and the utterance started in (q)) – and we used to bring them two down on the trolley car – the repetition of the trolley cars (q) and bring (s) from the repair self-initiation helps us (and Anne) infer that them two (x) – which refers to Jesse and Kenny in the previous sentence – also supplies the missing referent in the interrupted noun phrase the- in (q).

Both the wealth of detail provided in the repair, and the cohesive ties between its self-initiation and self-completion, show recipient design – the process whereby a speaker takes the listener into account when presenting information. The information that Ceil added about Ann (my cousin, Ann?), for example, showed that she had gauged Anne’s lack of familiarity with members of her extended family. Likewise, Ceil’s repetition of trolley car from the repair self-initiation to its self-completion attended to Anne’s need to place the referent back into the description that had been interrupted.

What else can we notice about spoken discourse from the transcript in (3)? What about the ways in which each person contributes to the discourse? If we look at the sheer amount of talk from each person, it looks like Ceil was the main speaker. And although Ceil and Anne both took turns at talk, what they said in those turns was quite different. Anne asked Ceil a question (That’s- that’s the Italian market, huh? (e)) that drew upon Ceil’s knowledge of the city. Anne also agreed with points that Ceil had made: Yeh (h) and Oh, I do, too (i). And while Ceil was adding information to help Anne recognize the referent, Anne used back channels to signal Ceil that it is okay for her to continue talking. (Back channels are brief utterances like mmhmm that speakers use to signal they are paying attention, but don’t want to talk just yet.)

Comparing transcripts

Although close analysis of a single transcript can help us learn about discourse, gathering together different transcripts and comparing them is also essential. The tools that people use when they are talking to one another are often the same at some level (e.g. turn-taking recurs in almost all discourse) but different at other levels (e.g. the ways that turns are exchanged may differ). Capturing what is the same, and identifying what is different, is an important part of discourse analysis. We all engage in many different kinds of discourse throughout our daily lives and don’t improvise or construct new rules each and every time we speak. Rather, much of our communicative competence consists of general principles about how to speak and ways of modifying those principles to specific circumstances. If we want to build up generalizations about discourse, then, a good way to do it is to gather together examples of discourse that are the same in some ways (e.g. all from sociolinguistic interviews) but different in other ways (e.g. from different people). Likewise, it is useful to compare the discourse of different kinds of speech situations and speech events in order to see how the social features of those situations and events are related to the way we use language.

The transcript in (4) below is also from a sociolinguistic interview, but the speech events and speech acts that occur are quite different. In (4), Jack, his wife Freda, and their nephew Rob have been talking with me about different facets of life in Philadelphia, the city whose speech I have been studying. Jack has been boasting about his childhood friendship with Joey Gottlieb, who became a well-known comedian known as Joey Bishop. The section below begins when Freda mentions that Jack and Joey shared their Bar Mitzvah (a rite of passage for Jewish boys when they turn thirteen).

The interchange among Jack, Freda, Rob, and me (Debby) changes shape during the course of talk. From lines (a) to (ll), for example, several people are active speakers, sometimes speaking at the same time. Jack and Freda overlap, for example, in lines (p) to (s) after Jack has mentioned his high school teacher, in (k) and (l). Then two different conversations develop: Freda asks me about my mother (who used to be a teacher) while Jack continues to talk about his own high school teacher (in lines (t) to (aa)). Jack eventually dominates the floor when he tells a story in lines (gg) to (eee).

Adjacency pairs

The conversations in (4) and (3) are both initiated by interviewers’ questions. Semantically, questions are incomplete propositions; they are missing the “who,” “what,” when,” “where,” “why,” or “how” of a proposition, or their polarity (positive or negative) is unknown (did something happen or not? is a description accurate?). The propositional incompleteness of questions is part of their discourse function. They perform speech acts (requests for information or action) that have interactional consequences; questions open up a “slot” in which whatever is heard next will be assessed as an answer (“completing” the question). This kind of relationship between two utterances in discourse is called an adjacency pair – a two-part sequence in which the first part sets up a strong expectation that a particular second part will be provided. This expectation is so strong that the first part constrains the interpretation of the second part. For example, even a silence after a question will be interpreted as a kind of answer – if only a reluctance or inability to provide an answer.

The two parts of an adjacency pair help people organize their conversations because they set up expectations for what will happen next. These expectations help both speakers and hearers. If I thank you for doing me a favor, for example, that gives you clues about what I’m thinking and what you should do next, making it easier for you to know what to say. I also simplify my own job since I know what to listen for. Indeed, a missing “second part” of an adjacency pair can be disconcerting; we typically listen for closure of the adjacency pair (e.g. why didn’t he say You’re welcome?), even those that come much later than the first part.

Participation frameworks

We saw in example (3) how Ceil made a lengthy self-repair so that Anne would know who she was talking about. Jack also introduces a new referent into his discourse, but he uses a question to do so, in (k):

The information that Jack provides about the teacher is enough for Freda to recognize the “teacher” referent (Yes I do (m)). Because Jack’s description does not include the teacher’s name, Rob interprets it as a self-initiation of a repair sequence and offers an other-repair – a repair of a problematic item in another speaker’s utterance. Rob provides the name of Jack’s referent (Lamberton? (n)). Rob and Freda speak at the same time and overlap with Jack’s continuing description of the teacher (l-o). Jack’s description of the teacher in (l) could have ended where Freda and Rob started talking, and they anticipated this turn-transition place – a place often marked by syntactic closure, intonational boundary, and/or propositional completion where another may begin a turn at talk.

Rob and Freda’s differing responses in (m) and (n) show that listeners may react to different aspects of what another person has said. The ways that people interacting with one another take responsibility for speaking, listening, and acting are part of the participation framework. Sometimes participation frameworks change when people adopt different roles and/or split off into separate interactions, perhaps to pursue divergent topics or establish a different relationship. For example, when Freda brings up my mother (who had been a teacher) in (t), (v), and (x), and then asks How m- long has your mother been teaching? (bb), she invites me to take a different, more active role in the conversation.

Freda’s attempt to create a new participation framework overlaps with Jack’s continuing talk about his music teacher, in (u) and (w). Jack opens a new participant framework when he tells a story (from lines (aa) to (ccc)) in which he holds the floor pretty much on his own. But he had to signal the shift to this turn-taking and storytelling status in (y), (aa), and (gg) with the repetition of the phrase one day.

Once Jack gains the floor in (gg), he tells a narrative, a recounting of an experience in which past events are told in the order in which they occurred. Jack’s narrative is about a recital in which he and Joey were supposed to play an elegy, a formal (often mournful) musical composition. Joey, however, jazzes it up by playing a cartoon jingle (“Shave and a haircut, two bits!”) instead of the expected chords.

Narratives

Narratives contrast with other genres and speech events in a number of ways. Narratives organize information differently than other genres, such as descriptions, explanations, and lists. For example, narratives present events in temporal order of occurrence, but lists need not, as we can see in Jack’s list of habitual activities with Joey ((c) through (g)). Narratives have a different participation framework; storytellers tend to hold the floor alone. And finally, the content of a fully formed oral narrative of personal experience (in American English) has a relatively fixed structure, consisting of the following parts (usually in this order):

- Abstract: a summary of the experience or its point

- Orientation: background description (who, where, when, why, how)

- Complicating action: “what happened,” a series of temporally ordered events (often called “narrative” clauses) that have beginning and end points

- Evaluation: syntactic, prosodic, textual alterations of the narrative norm that highlight important parts of the story and/or help convey why the story is being told (i.e. the point of the story)

- Coda: closure that brings the “past” of the narrative to the “present” of the interaction in which it was told

Whereas it is relatively easy to identify the abstract, complicating action, and coda in Jack’s narrative, it may be more difficult to identify the orientation and evaluation. Many orientations describe the background scene – who is present, where, and when. Jack had already introduced his friend Joey and the teacher prior to the narrative, but Jack does spend a fair amount of time, in lines (ll) to (oo), familiarizing his listeners with what typically happens in a recital. This is crucial for the point of the story; if the audience doesn’t have a schema (a set of structured expectations of what is supposed to happen), then they can’t recognize a deviation from expectation. Yet the break in expectation is what underlies the humor in Jack’s story and is crucial for its point.

But what actually is the point of the story? Here we need to turn to the evaluation. One way in which people telling stories often indicate evaluation is by using the historical present tense – the use of the present tense to convey past events. The historical present is buried within the language of the narrative clauses, as in So, everything is set fine (pp) through and in a chord, he goes DAA da da da da, da DAAA! (tt). Also highlighting the humor of the story is Jack’s singing of the tune; breaking into melody is clearly noticeable through its contrast with the rest of the story. And clearly the humor of Joey’s musical prank works; the audience laughs (Well the whole: audience broke up! (uu)), as does the teacher in Even this teacher, this one that-she laughed (ccc).

Summary: spoken discourse

In this section, we have illustrated how different configurations of language work together to produce coherence in spoken discourse. We have highlighted some of the ways that speakers try to achieve several goals, sometimes simultaneously:

- introducing new information in relation to the anticipated needs of their hearers

- linking information through cohesive ties

- repairing errors

- initiating adjacency pairs with actions that have sequential consequences for listeners’ next actions

Together, interlocutors distribute turns at talk and develop different frameworks in which to interact. Discourse consists of a variety of different units (for example, clauses, sentences, turns, and speech acts) that tie together different strands of talk. As we will see in the next section, not all of these processes appear in written discourse. Those that do, work somewhat differently because of the complex differences between spoken and written discourse.

Language variation according to the situation in which it is used is called register variation, and varieties of a language that are typical of a particular situation of use are called registers. Each situation makes its own communicative demands – informational, social, referential, expressive – and people use the features of their language which meet the communicative demands of the situation. The set of language features – phonological, lexical, syntactic, and pragmatic – which is normally used to meet the demands of a particular communicative situation is the register of that situation.

Sociolinguist Dell Hymes proposed the acronym SPEAKING as a mnemonic (or memory aid) for remembering the components of most speech situations. Think of the SPEAKING mnemonic as a grid; each element is a variable, a range of possible values which may describe the situation. Filling in the value of each variable in the SPEAKING grid goes a long way toward describing a given communicative situation.

- Setting

-

Physical location and social significance

- Participants

-

Respective social status, local roles in interaction

- Ends

-

Purpose of the event, respective goals of the participants

- Act sequences

-

Speech acts that are functionally or conventionally appropriate to the situation

- Key

-

Tone or mood (e.g. serious, ironic)

- Instrumentalities

-

Mode of communication (e.g. spoken, written, via telephone)

- Norms

-

Expectations of behavior and their interpretation

- Genres

-

Type of event (e.g. conversation, lecture, sermon)

To show how the SPEAKING grid helps describe a speech situation – and how the situation demands particular uses of language – imagine a cooking class:

- The setting is a kitchen being used as a classroom, so tables have been arranged to allow students to see and practice the techniques the teacher is demonstrating. The shared physical setting allows use of definite articles (“Put the butter in the saucepan”) and deictic pronouns (“Now add this to that”), as well as first- and second-person pronouns and temporal references (“Now I want you to stir briskly for two minutes”). Food and cooking vocabulary are also frequent.

- The participants are the chef/teacher and the students/clients. Their physical placement in the kitchen reflects their respective roles, as does their use of language. For example, many of the teacher’s verbs are imperatives, while the students use the auxiliary do frequently to ask questions (e.g. “How do I…?” and “Does this look right?”).

- The ends of the speech event are several. Teacher and students have a shared goal of transferring knowledge about cooking, but have different relations to that goal. The students’ goal is to learn new cooking techniques and recipes – and probably to enjoy the process, as well. The teacher shares these goals but mainly as a means toward the broader goal of keeping clients satisfied and generating new business.

- The cooking class includes a number of routinized act sequences. At the beginning of the class, the teacher greets the students, then introduces the topic of that day’s class. The teacher then demonstrates and explains cooking techniques, offering definitions of technical terms and verbal explanations of physical actions (like chopping, slicing, etc.). The students attempt to imitate the teacher’s actions, ask questions, seek clarification, and request confirmation that they are performing the actions correctly. These acts are sequenced in conventionalized routines; for example, the teacher gives a directive (“Stir briskly for two minutes”), a student asks for clarification (“Like this?”), and the teacher offers confirmation (“Yes, good”) or further instruction (“A little slower”).

- The key of the class varies, from serious (instructions and warnings) to entertaining (anecdotes about fallen soufflés and burned sauces). Instructions are characterized by (present-tense) imperative verbs and reference to objects in the classroom (“Take the pan of onions off the flame”), while anecdotes are characterized by past-tense verbs and third-person reference to nonpresent people and objects (“The customer began fanning his mouth and drank three glasses of water”).

- The main instrumentality of the class is spoken discourse, but students may refer to written recipes or take notes. Recipes share some of the features of the teacher’s instructions (directive verbs, definite articles) but do not include the teacher’s definitions and explanations. Students use abbreviations and delete articles to save time and space in their notes (“Add 1 Tsp sug to sauce”).

- The norms of interaction include, for example, recognition that suggestions from the teacher (“You might want to turn down the flame”) are usually directives, and that requests by students for clarification (“Am I doing this right?”) are often requests for the teacher’s approval (“Yes, good job”).

- The genre of the event is “class.” This helps teacher and students to recognize the range of language use that is conventionally appropriate to the situation.

All of the linguistic and discourse features mentioned above co-occur frequently in cooking classes and therefore are part of the register of a cooking class.

Following the work of Douglas Biber, linguists have identified the sets of linguistic features that tend to co-occur across many speech (and writing) situations. The main communicative functions that those sets of features serve include interpersonal involvement, presentation of information, narration, description, and persuasion. With our varying emphases on these basic communicative tools, we mark and construct each speech situation.

Written discourse

Learning to speak seems to occur without much effort; it is woven seamlessly into our early childhood socialization. But learning to write is often a formal and explicit process that includes instruction in graphic conventions (printing letters as well as connecting them together in script), technology (how to use a keyboard and manage computer files), punctuation (e.g. when to use commas, semi-colons, and colons) and rules of “correct” grammar (e.g. “No prepositions at the ends of sentences”). Why can’t we just write the way we speak? One reason is that written texts have longevity, a “shelf life”; they can be read and reread and examined more closely than transitory speech. Sometimes written texts also become part of a cultural canon; they serve as official bearers of wisdom, insight, and institutional knowledge that can be passed down over time and generation. And this means that ideologies about what language should be – the standard variety with the power of social institutions behind it (see Chapter 11) – often have a strong impact on the way we write.

Of course, not all written discourse is held up to such high standards. In addition to literature, chapters in academic textbooks, legal briefs, and minutes of corporate meetings, we find comic books, self-help manuals, grocery lists, and diaries. Clearly, the latter genres of written discourse are not subject to the same standards of correctness as the former. Yet, despite the wide-ranging differences among written genres, they all differ from spoken discourse in several crucial ways.

Fragmentation and integration

One major difference is that speaking is faster than writing. This difference has an impact on the final product. When speaking, we can move more rapidly from one idea or thought to another, resulting in what Chafe (1982) calls fragmentation, the segmentation of information into small, syntactically simple chunks of language that present roughly one idea at a time. When writing, we have time to mold a group of ideas into a complex whole in which various types and levels of information are integrated into sentences. Integration is thus the arrangement of information into long, syntactically complex chunks of language that present more than one idea at a time.

We can see the difference between fragmentation and integration by looking at the introduction of new referents into discourse – people, places, or things that have not yet been mentioned. Recall, for example, Ceil’s introduction of the boys accompanying her and Ann on the trolley car in (3): like we only had- like Ann and I, we-my cousin, Ann? We- like she had Jesse and I had my Kenny; and we used to bring them two down on the trolley car. However, if Ceil were writing a memory book about the Italian market, she might use a complex sentence such as the following: Before our other children were born, my cousin Ann and I used to take our two boys, Jesse and Kenny, on the trolley car to the Italian market. Notice that the referring expression itself (our two boys, Jesse and Kenny) would be buried within a complex of other information about time, activity, and other referents, and followed by a description of where they were going and how they got there – all in one sentence! The crucial information about the referent, then, would be integrated with other information in one complex syntactic unit, rather than fragmented into different tone units (segments of speech production that are bounded by changes in timing, intonation, and pitch) and turns at talk.

Writing to be read

Another crucial difference between spoken and written discourse is the role of the recipient. In spoken genres, the recipient is a co-participant in the evolving discourse in two ways: (a) the recipient provides feedback through back channels or by asking for clarification; (b) the recipient gets a chance to become a speaker. These differences boil down to differences in participation framework. In spoken discourse, participants are more likely to face similar opportunities (and challenges) as they alternate between the roles of “speaker” and “listener.” How participants manage these shifts can have profound impacts on the overall flow of discourse. Recall, for example, how Jack had to maneuver around the alternate conversations that developed between Freda and Debby before he could begin his story. Even then, he could pursue his story only after he had secured Freda’s attention by bringing up a recently shared experience.

Producers and recipients of written discourse interact in very different participation frameworks than those engaged in spoken discourse. Writers have to anticipate the informational needs of their intended recipients, as well as what will maintain readers’ interest, without the benefit of immediate feedback. Writers try to be clear and to create involvement with their material and with their intended readers. Here they can draw upon structures that are easy for readers to process (like short and simple sentences), as well as dramatic devices (like metaphor and visual imagery) to make it exciting and engrossing. And just as speakers orient what they say to their listeners’ needs and interests, so too writers try to anticipate a particular type of reader.

Depending on how writers construct their “ideal” readers, they use different aspects of language to maintain readers’ interest and to make the text relevant to their readers’ needs and goals. This means that writers – like speakers – also design their discourse for their projected recipients. A good way to see this is to compare different written genres with one another. Like the comparison of spoken genres that occur during different speech events and speech situations, scholars sometimes call this a comparison between registers, ways of using language that reflect different facets of its context (e.g. participants, goals, and setting).

The written texts in (5a) and (5b) share some general register features, but they also differ in various ways. (5a) is from a newspaper column in which young adults seek advice about their personal relationships. (5b) is from the back of a bottle of hair conditioner.

Let’s look first at the content of these texts and how they are constructed: what is being conveyed and how? Both texts are about a problem and a solution. The problem in each is how to manage something – commitment in a relationship, unruly hair – whose solution may require the reader to be assertive, either verbally (Should I ask …) or physically (to control styles). Each solution requires a transformation of some sort from an initial state. Asking about commitment requires being reconditioned from the way one was raised. So too, gaining body and lustre in one’s hair is the result of a conditioner.

Both texts rely upon the integration of more than one idea in each sentence to present their respective problems and solutions. For example, the last sentence of C’s advice (5a) integrates two pieces of information about asking to be exclusive: it is honest; it is a compliment. The last sentence in the HEADRESS description (5b) also integrates two solutions – time released Antioxidants and UVA and UVB Protectors – to guard against the problem of harsh environmental elements.

These sentences don’t just present solutions to problems; they also positively evaluate those solutions. The Dear Carolyn text calls the solution (asking to be exclusive) such a compliment that it would be a shame to withhold it; the alternative (not asking to be exclusive) is negatively evaluated (a shame). In the HEADRESS text, the product’s ingredients provide protection so hair continuously shines with radiant health, evoking glowing, positive images, reminiscent of the sun. So although neither text comes right out and says “this is the right solution for you!,” this message is clearly implied through the texts.

These problem/solution texts also construct and reflect their participation frameworks – the roles and identities of the writer and the reader. The topic of each text is likely to be relevant to a limited set of readers – young women – simply because the problems concern a boyfriend (5a) and hair (5b). Despite this broad similarity, the two texts set up different relationships and identities. Although we don’t know anything about the identity of the person asking for advice in (5a), the identity of the person giving advice appears several times, encouraging reader involvement with the writer as a real person. In contrast, in the HEADRESS text the only information about the source of the text is the name of a company and how to contact it.

The language of the two texts also creates different types of involvement between writer and reader, which in turn help to construct their respective social identities. Dear Carolyn uses casual terms like a guy and stuff like that, typical of a young adult chatting with a friend on the phone. The HEADRESS description is filled with referring expressions that are not part of our everyday vocabulary – e.g. thermal appliance instead of ‘hairdryer’ – or that we may not even know (Panthenol? Vegetable Ceramides?). This unfamiliarity lends the text an air of scientific legitimacy. Whereas the advice column resembles a chat between friends, the HEADRESS text mimics a consultation with an expert professional.

Differences in what is being conveyed (and how), and identities (and relationship) of writer and reader, come together in the way each text proposes a solution to the problem. In the advice column, C’s response establishes camaraderie (I was raised that way, too). In HEADRESS, on the other hand, the DIRECTIONS are a list of imperative sentences: there are no subject pronouns, just verbs (apply, rub, distribute, comb) that instruct and command, conveying a sense of routine procedure, not personal concern.

Dividing discourse by how it is created – by writing or speaking – overlooks the many different genres and registers within each type. But there are still some overall differences. Spoken discourse is more fragmented and written discourse is more integrated. Although people are certainly judged by the way they speak, the longevity of many written texts subjects them to further and more intense scrutiny and to higher standards. All language users, however, orient their discourse to whoever will hear (or read) what they say (or write). Whereas speakers have the chance to continuously adjust what they say – sometimes with the help of their listeners – writers have the luxury of more time. Yet both end up honing their messages, shaping and reshaping them to structure information in ways that set up nuanced and complex relationships with their recipients.

Language functions

All approaches to discourse analysis address the functions of language, the structures of texts, and the relationship between text and context. A main function of language is referential: we use language to convey information about entities (e.g. people, objects), as well as their attributes, actions, and relationships. But language also has social and expressive functions that allow us to do things – like thanking, boasting, insulting, and apologizing – that convey to others how we feel about them and other things. We also use language to persuade others of our convictions and urge them toward action by crafting texts that demonstrate the logic and appeal of those convictions.

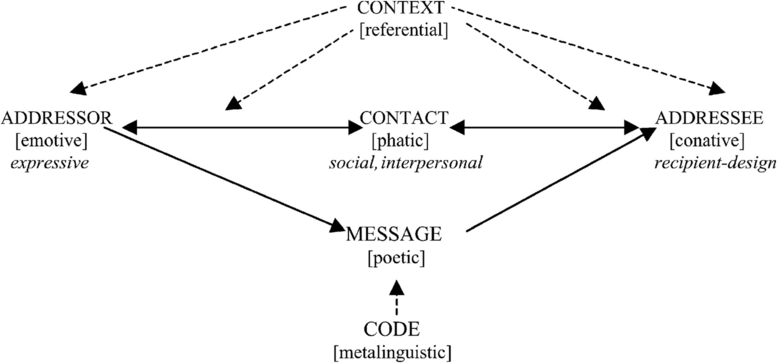

Figure 5.1 (adapted and modified from Jakobson 1960) presents six functions of language – six jobs that people accomplish by using language. Jakobson’s model of language functions represents the speech situation as a multidimensional set of relationships, a bit like a multifaceted diamond.

Figure 5.1 Speech situation and functions. Each facet of the situation is in upper case; the language function is in brackets. Terms that have been used interchangeably with Jakobson’s terms are in italics.

When we view the speech situation from different angles, we see different facets, different connections between the components of the speech situation, the features of language used, and the communicative function performed by that language. Each language function is related to a different facet of the speech situation. The arrows in Figure 5.1 indicate the relationship between speech situation and function, and suggest how different aspects of the speech situation – and different functions – are related to one another. The unbroken arrows indicate paths by which ADDRESSOR and ADDRESSEE are connected – back and forth through CONTACT or unidirectionally through a MESSAGE. The arrows in dashes indicate that CONTEXT pervades the way ADDRESSOR and ADDRESSEE speak, as well as the circumstances of their CONTACT. The dotted arrow from CODE to MESSAGE highlights the contribution of language to the MESSAGE.

- Referential function: sentences focusing on aspects of the speech situation mainly serve a referential function. For example, a sentence like The coffee is hot relates a proposition about some aspect of the participants’ shared context to their respective roles in the interaction and the circumstances of their contact (some reason for remarking on the temperature of the coffee). However, CONTEXT influences the ADDRESSOR’S and ADDRESSEE’S identities and the kind of CONTACT between them. For example, if your close friend works part time in a coffee shop, when you go in to buy coffee, the context of your contact will (at least partially) include a waiter/customer relationship.

- Phatic function: sentences focusing on the relationship (CONTACT) between participants mainly serve a phatic function. For example, Hi! Good to see you! provides little information about the surrounding context, but as a first part of a greeting sequence, it initiates an interaction and a renegotiation of the status of the participants’ relationship.

- Poetic function: sentences that focus on the MESSAGE itself serve mainly a poetic function. For example, Carl Sandburg’s line, The fog comes in on little cat feet, manipulates the CODE to convey the silent approach of the fog through metaphor.

- Emotive function: sentences that express the impact of some facet of the external world (context) or internal world (feelings, sensations) on the ADDRESSOR mainly serve the emotive function. For example, I am hungry states an internal condition of the ADDRESSOR. But because it may be interpreted as a request that the ADDRESSEE make dinner it may also have a conative function.

- Conative function: sentences that focus on the relation of the ADDRESSEE to the context or the interaction mainly serve the conative function. For example, Are you hungry? can be interpreted as either a request for information from the addressee or as an invitation to join the addressor for dinner.

- Metalinguistic function: sentences focusing on the relation between code and situation serve mainly a metalinguistic function. For example, asking Did you just say “Don” or “Dawn” was coming? focuses on the pronunciation and reference of some prior word.

Sentences typically serve more than one function at a time. Although a sentence may have a primary function, it is likely to be multifunctional. Suppose, for example, someone says What time is it? The sentence’s primary function is conative: it is a question that requests something of the addressee. But it may also have a phatic function if it opens contact. And it certainly has an emotive function (it conveys a need of the addressor) and a referential function (it makes reference to the world outside language).

Planes of discourse

Jakobson’s model of language functions stresses the context “beyond the sentence,” but it ignores the text – the unit of language “above the sentence.” What we say or write never occurs in a vacuum: it is always surrounded by other information in other utterances. The accumulation of information through successive chunks of language complicates the view of multifunctionality presented in Jakobson’s model. Since functions pile up with each successive sentence, how do we manage to sort out which functions we should pay attention to and which we may safely ignore? How are sentences with multiple functions strung together to create coherent texts?

To answer this question, we must shift our attention from the “sentence” to the utterance, a contextualized sentence. Whereas a sentence is a string of words put together by the grammatical rules of a language, an utterance is the realization of a sentence in a textual and social context – including both the utterances which surround it and the situation in which it is uttered. An utterance is the intersection of many planes of context, and as we speak and listen, we rely on these intersecting planes of context to convey and interpret the meaning of each utterance. An utterance thus expresses far more meaning than the sentence it contains.

The examples in (6) can help disentangle the difference between sentence and utterance.

| (6) |

|

Although the sentences are the same, the three occurrences of Discourse analysis is fun in (6) are three different utterances, because they are produced in different contexts. Although (6a) and (6b) appear in the same social context (as examples presented in a textbook), there is a difference in their textual contexts: (6a) is the first appearance of the sentence, and (6b) is the second appearance (a repetition) of the sentence. (6a) and (6b) both differ from (6c), as well. Although (6c) is an illustration in a textbook, it is also part of an interaction between two interlocutors, so it has a different social context than (6a) and (6b).

Focusing on utterances allows us to see how several planes of context are related to, and expressed through, the language used in an utterance. Like the facets of a diamond, an utterance simultaneously has meaning as:

- a reflection of a social relationship (who are you? who am I?)

- part of a social exchange (who will talk now?)

- a speech act (what are you doing through your words?)

- shared knowledge (what can I assume you already know?)

- a proposition (what are you saying about the world?)

Each utterance is simultaneously part of – and has meaning in – a participation framework, an exchange structure, an act structure, an information state, and an idea structure. Each utterance is connected to other utterances and to the context on each of these planes of discourse; part of each utterance’s meaning is these connections. Speakers indicate which aspects of meaning of a prior utterance they are emphasizing by the construction and focus of their own “next” utterances in a discourse.

Participation framework

The participation framework is the way that people organize and maintain an interaction by adopting and adapting roles, identities, and ways of acting and interacting. Included are all aspects of the relationship between a speaker and hearer that become relevant whenever they are interacting with one another, either in the “real time” of spoken discourse or the “displaced time” of written texts. We continuously align with others through what we say. For example, we frequently depend upon what is being said (and how it is being said) to assess the status of our relationship with another speaker: is he trying to convince me to take his point of view? Does she seem distant? Have I hurt her feelings? Why does he now seem skeptical about our plan to go out tonight? What we say and how we say it are thus critical to the formation, management, and negotiation of our interpersonal relationships.

Exchange structure

The exchange structure concerns the way people take turns in talk: how do we know when to start talking? Do we ever overlap, and if so, where, when, how and why? What does such overlap mean to the person already talking? How is exchange in multiparty talk managed? Because participation in spoken discourse typically requires alternating between the roles of speaker and hearer, the exchange structure is connected to the participation framework. Thus we might find that turn-taking would differ along with participation framework. During a job interview, for example, we might wait for a potential employer to finish his/her question before we start the answer. When gossiping or joking around with an old friend, however, we might end up talking at the same time, viewing our overlapping turns as welcome signs of enthusiasm and solidarity.

Act structures

Act structures are ordered sequences of actions performed through speech. For example, the first parts of adjacency pairs like questions, greetings, and compliments constrain the interpretation of the following utterance (and the role of its speaker). An accusation presents the accused with the act choices of confession, denial, or counter-accusation. An accepted bet will eventually recast one participant as the winner and the other as the loser (and maybe debtor). Speech acts have still other consequences for participants and their relationship. Almost all speech acts – commands, questions, requests, hints, compliments, warnings, promises, denials – allow people to exert different degrees of responsibility and control that create feelings of distance or solidarity, power or equality between speaker and hearer.

Information state

The information state is the distribution of knowledge among people interacting with one another. Speakers take into account their listeners’ informational needs as they construct their utterances: what common knowledge can the speaker assume? How does he/she present brand new information?

Often we can see changes in the information state by looking at the nuts and bolts of repairs, like Ceil’s repairs in example (3) that filled in information that Anne didn’t have. But we can also find speakers accommodating to their hearers’ knowledge by looking at the choice of words, and their arrangement, in sentences that don’t undergo repair. For example, speakers in conversation mix together old information (which they believe their addressees know or can figure out) with new information (which they believe their addressees don’t know and can’t figure out). The utterances in (7a–c) all introduce new referents into a conversation:

| (7) |

|

Syntactic subjects – the italicized forms at the beginning of the sentences in (7) – rarely introduce new referents to a conversation. The minimal information conveyed by simple and uninformative initial clauses (like there is, they have, and y’know) puts the focus on the new information at the end of the sentence.

Idea structure

Idea structure concerns the organization of information within a sentence and the organization of propositions in a text: how bits of information are linked together within, and across, sentences. Different genres typically have different idea structures. Recall the problem-solution organization of the advice column and hair conditioner label. Recall also Jack’s narrative in example (4). Once Jack got started on his story, each clause presented an event in the order in which it was presumed to have occurred. A narrative has an idea structure with a linear organization based on temporal progression. The email entries below show two other genres – a list (8) and an explanation (9).

| (8) |

Okay, here’s the grocery list. Don’t forget the fruit – we need apples, pears, if they’re ripe enough, bananas. And we also need some milk and eggs. And if you can find something good for dessert, like some chocolate chip cookies or small pastries, that would be great! |

| (9) |

I don’t really think we should go out tonight. For one thing, it’s supposed to snow. And I’m really tired. I just finished work and would rather just watch a movie on TV or something. So is that okay with you? |

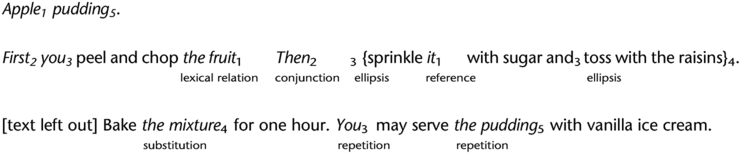

Repetition is one of six language devices that help to join information together as a text by providing cohesive ties (Halliday and Hasan 1976) among different sentences. Other cohesive devices are reference (e.g. through pronouns), substitution (using paraphrases), ellipsis (deleting material that is easily recoverable from the sentence or text), conjunction (words like and or but that connect sentences), and lexical relations (e.g. words whose meanings are semantically related, e.g. fruit and pear). The following short excerpt from a recipe illustrates the different kinds of cohesive ties.

Italicized words and phrases sharing the same subscript number are connected by a cohesive tie (labeled underneath each tie). So, for example, Apple is tied to the fruit by the cohesive device of lexical relation, and First and Then are tied by conjunction. The first reference to the reader (you) is tied to the elided subject pronouns of the following verb phrases and repeated you in the last sentence, and the mixture is a substitution for the product of those two verb phrases, indicated by curly brackets {}. Finally, the repetition of pudding, in the title and the last sentence, bookends the whole text.

Out of 36 words in the excerpt (counting the elided subject pronouns), more than half are linked in cohesive ties which help the reader understand the meaning of not just each sentence, but the entire text.

The idea structure of the list in (8) reflects semantic relationships among the items to be bought at the food store. Fruit is a superordinate set that includes apples, pears, and bananas. Milk and eggs are items that both require refrigeration in the dairy section of stores. And dessert includes cookies and pastries. The idea structure of the explanation in (9), however, is based on the relationship between a conclusion (not to go out) and the events (or states) that justify that conclusion (weather, physical state, time, alternative activity).

Linking together planes of discourse

Although we have been discussing each plane of discourse separately, we need to remember that every utterance is simultaneously part of – and has meaning on – different planes of discourse. We can get a clearer picture of these relationships by taking a look at the discourse in (10), an excerpt from an interaction between a librarian and a patron at the reference desk of a public library.

| (10) |

|

Part of the librarian’s job is to help patrons find material in the library. After opening this speech situation (e.g. with eye contact or excuse me), patrons typically use the speech act “request” to get help. Although the patron doesn’t say anything like “Can you give me…” or “Do you have…,” her utterance still performs the speech act of a request. We know this (as do librarians and library patrons) because the participation framework (the identities and roles of librarians and patrons) helps us recognize that an utterance that sounds as if it is asserting the existence of a report (There used to be a monthly report (a)) is also performing a request.

Notice that the utterance about the existence of the monthly report appears as a long and complex sentence spread over four lines in the transcript ((a), (b), (d), and (e)). These lines reflect different tone units, segments of speech production that are bounded by changes in timing, intonation, and pitch. Because the sentence is spread out over multiple tone units, it ends up bypassing turn-transition places (locations at which the listener is given the option of taking a turn) and allows the patron to complete the speech act (a request) that is pivotal to the speech event and speech situation.

The division of the patron’s long sentence into four tone units also reflects the information state and the recipient design of the utterance for the librarian. The patron pauses after providing two pieces of information about the item she’s looking for: its frequency (a monthly report) and source (that comes from S-Securities Exchange Commission). This pause is an opportunity for the librarian to display her recognition of the requested item and to comply with the request. When that doesn’t happen, the patron continues her description of the report, in (b), (d), and (e), pausing after each new piece of potential identifying information to give the librarian another chance to respond. The pauses at the turn-transition places after (a), (b), (d), and (e) make it easier for the librarian to complete the adjacency pair and respond to the patron’s request at the earliest possible point. The act structure, the participation structure, the exchange structure, the information state, and the idea structure thus reinforce each other to make the production and the interpretation of the request (and its response) clear and efficient.

Chapter summary

Discourse is made up of patterned arrangements of smaller units, such as propositions, speech acts, and conversational turns. But discourse becomes more than the sum of its smaller parts. It becomes a coherent unit through both “bottom-up” and “top-down” processes. We construct coherence bottom-up in real time by building upon our own, and each others’, prior utterances and their various facets of meaning. At the same time, however, our sense of the larger activity in which we are participating – the speech event, speech situation, and genre that we perceive ourselves to be constructing – provides an overall top-down frame for organizing those smaller units of the discourse. For example, turns at talk are negotiated as participants speak, but participants also are aware of larger expectations about how to share the “floor” that are imposed by the speech event (e.g. a discussion) in a speech situation (e.g. a classroom). Thus the very same turn-taking pattern may take on very different meanings depending on whether it is taking place in a classroom, in a courtroom, or during a first date.

The bottom-up and top-down organizations of discourse work in synchrony. The overall frame helps us figure out how to interpret what is being said and done. It also helps us figure out where to place the smaller units in relation to one another. Yet choices that we make about the smaller units – should I take a turn now? should I issue a direct order or make a more subtle hint? – can also alter the general definition of what is “going on” in a situation. The combination and coordination of all the different facets of discourse – the structures that they create and the frames that they reflect – are what gives discourse its coherence, our overall sense of what is going on.

The multifaceted nature of discourse also arises because we try to achieve several goals when we speak to each other, often all at the same time. We verbalize thoughts, introduce new information, repair errors in what we say, take turns at talk, think of others, perform acts, display identities and relationships. We are continuously anticipating what our recipients need (e.g. how much information do they need?) and want (e.g. how polite do they expect me to be?). We achieve these multiple goals when we are speaking by using a range of different units, including sentences, tone units, utterances, and speech acts, whose functional links to one another help tie together different planes of discourse.

Discourse analyses – peering into the small details of moment-by-moment talk – can be very detailed. And such details are in keeping with the assumption that knowledge and meaning are developed, and displayed, through social actions and recurrent practices, both of which depend upon language. Yet for some scholars the scope of discourse stretches beyond language and its immediate context of use to include what Gee (1999: 17) has called “Discourse” (with a capital D): “socially accepted associations among ways of using language, of thinking, valuing, acting and interacting, in the ‘right’ places and at the ‘right’ times with the ‘right’ objects.” This conception of Discourse reaches way above the sentence and even further beyond the contexts of speech act, speech event, and speech situations. It makes explicit that our communicative competence – our knowledge of how to use language in everyday life – is an integral part of our culture.

Exercises

What inferences would you draw from the two conversational excerpts below? What is the social relationship? The setting? And what features of “what is said” (e.g. what specific words and phrases?) allow you to make these inferences?

| (i) |

|

| (ii) |

|

Differences in the ways we use language to act and interact often arise through differences in their “context.” Collect ten to fifteen examples of phone openings, and ten to fifteen examples of face-to-face greetings. What differences between them can you identify in who talks when, and the use of words (e.g. hello, hi) and questions. What about differences within each context? Does the way you (or your interlocutors) talk seem to be related to how well you know each other, or when you’ve spoken to them last?

Try to change the discourse markers you use in your everyday conversations. For example, answer each question that someone asks you with well. Completely stop using like or y’know. Add and to every sentence or utterance. Keep a log of your own ability to make these changes. What changes were the hardest to make? What do the changes tell you about these discourse markers?

Identify question/answer adjacency pairs in the transcribed excerpts in this chapter. Analyze those adjacency pairs, as well as questions that you hear in classes and conversations, to answer the following:

Reread Jack’s story in example (4) in this chapter and answer the following questions: