Recently I saw a patient who had been diagnosed in 1983 with a malignant tumor in her right breast. For reasons of her own, she had refused any form of conventional treatment, including radiation, chemotherapy, and hormones. She told me that the tumor was quite large but had not spread to any lymph nodes under her arm.

“I think I’d better examine it,” I said, and she hesitated.

“I should warn you,” she said, “that most doctors are very frightened when they see this, because of its size. I generally don’t even let a doctor touch me, because the fear in their eyes makes me scared. On my own I’m not scared. You may not believe this, but I have never felt that I was in any danger. I can be shaken, though, when I see a doctor’s fear. They even say things like, ‘How dare you be so cruel to your husband by not having surgery.’

“I thought that maybe a woman doctor would be more understanding, but when I went to one, she was more horrified than the rest. She asked me, ‘Why did you come to see me if you aren’t going to let me remove that thing?’ And I said, ‘Because I just want you to monitor it—it has grown slightly in the past five years, and I want it followed. Almost shaking, she stood up and told me, ‘Don’t come back to see me unless you want that thing removed. I can’t stand the sight of it.’ ”

I had no idea what my reaction would be. About half of the women diagnosed with breast cancer have localized tumors confined to the breast. The standard treatment has been either to remove the breast or to remove the lump and radiate the site to kill any remaining cancer cells. In both cases, when there is no further follow-up treatment, 70 percent of patients do not have a recurrence in the next three years. With some sort of chemotherapy, ranging from mild to quite heavy, the proportion of long-term survivors can be raised to 90 percent. This woman had decided to defy odds that were very much in the patient’s favor—and yet she would not be the first to ignore doctors and survive.

When she lay on the examining table and I saw the tumor, I understood why her previous doctors had been shocked—it distended a large portion of her breast. I controlled my automatic reaction, and I hope no fear showed in my eyes. I sat down and held her hand, thinking. “Look,” I said softly, “I don’t believe you are in danger here. You have said that you don’t feel any danger, and that is good enough for me. But this tumor is a nuisance. You are denying yourself a more beautiful life by having to look after this. Why not go to a surgeon and have the nuisance removed?”

Apparently this struck her as an entirely new angle. She readily agreed that there was no advantage to keeping the tumor, and I referred her to a sympathetic surgeon.

One of her parting comments stays with me. “I don’t identify myself with this tumor,” she said serenely, “I know I am much more than it. It will come and go like the rest of me, but inside, I am not really touched by it.” When she left the office, she looked extremely happy.

I felt that this woman had reason on her side. The fear in a doctor’s eyes is a terrible stroke of condemnation, and in her position I would not have believed much in my chances of recovery. The impulses from my brain would not be saying, “I’m definitely going to recover.” Instead, they would be saying, “They tell me I’ll probably recover,” which is quite a different thing.

When a doctor looks at a patient and says, “You have breast cancer, but you’re going to get well,” what is he really saying? The answer is by no means certain. At one extreme, his reassuring words, if they are believable, may be enough to make the difference in the patient’s case. At the other extreme, if he actually thinks the patient is doomed, something in his voice will give that message, and from it a destructive confusion may set in.

Recently the term placebo was inverted into a new term, nocebo, to describe the negative effects of a doctor’s opinion. With placebo, you give a dummy drug and the patient responds because the doctor has told him that the drug will work. With nocebo, you give a viable drug, but the patient doesn’t respond, because the doctor has signaled that the drug isn’t going to work.

If you take a completely materialistic view, there seems no difference between the surgery this woman refused before and the one she agreed to now. Yet, now she identifies surgery with healing, whereas before it was violence. If a patient regards any treatment as violence, then his body will be flooded with negative emotions and the chemicals associated with them. It is well documented that in a climate of negativity, the ability to heal is greatly reduced—depressed people not only lower their immune response, for example, but even weaken their DNA’s ability to repair itself. So my patient had reasonable cause, I think, to wait until her emotions told her to go ahead.

This case reminds me that there are always two centers of action within people, the head and the heart. Medical statistics appeal to the head, but the heart keeps its own counsel. In recent years, alternative medicine has won much of its appeal on the basis of bringing back the heart, using love and caring to heal. Without these ingredients, the nocebo effect can run wild, for the surroundings of modern hospitals inject a powerful dose of it. The psychotic episodes that sometimes strike out of the blue in intensive care units show how unhealthy it is to hold people in sterile, confined spaces. (As a young child, my son showed an almost equal fascination with hospitals and prisons, which I trace to a fear he could not express. If he saw either institution from the car, he would invariably ask, “Daddy, are people dying in there?”)

The great drawback of proclaiming that we need to bring the heart back into medicine is that it punishes people for their emotional weaknesses. The heart can be very frail; it can be hardened by suffering, or just by life. Books on holistic healing like to say that sick people “need” their sickness. Mainstream psychiatry points its own finger when it says that chronic diseases can stand symbolically for self-punishment, revenge, or a deep feeling of worthlessness. I will not argue these insights, except to suggest that they may be harmful to the healing process rather than helpful. It is hard enough for any of us to face up to our emotional fallibility even at the best of times. Can we really be expected to reform when we are ill?

The deeper issue is that anything can function as a nocebo, just as anything can function as a placebo. It is not the dummy drug, the doctor’s bedside manner, or the antiseptic smell of a hospital that does harm or good; it is the patient’s interpretation of it. Therefore, the real war is not between the head and the heart. Something deeper, in the realm of silence, creates our view of reality.

The basic understanding most of us have about ourselves comes from thinking and feeling, which seems only natural. But we know very little about the field of silence and how it exercises control over us. The head and the heart, it seems, are not the whole person. The stream of consciousness, which is constantly full of thoughts, acts as a screen to keep silence hidden. The solid appearance of the physical body is another kind of screen, since we cannot see the molecules that are being constantly shuffled around inside us, much less their blueprint, which is what we would like to change.

The blueprint of reality is an important concept. Every impulse of intelligence gives rise to a thought or a molecule, which spends a certain time in the relative world—the world of the senses—before the next impulse follows. In that sense, every thought is like a piece of the future when it is created, a piece of the present when it is experienced, and a piece of the past after it has gone. As long as each impulse is healthy, the future is not unknown—it will flow naturally from the present, moment by moment. (This accounts for why people who make the most of every day tend to retain their mental faculties intact into old age; the stream of intelligence is never allowed to dry up.)

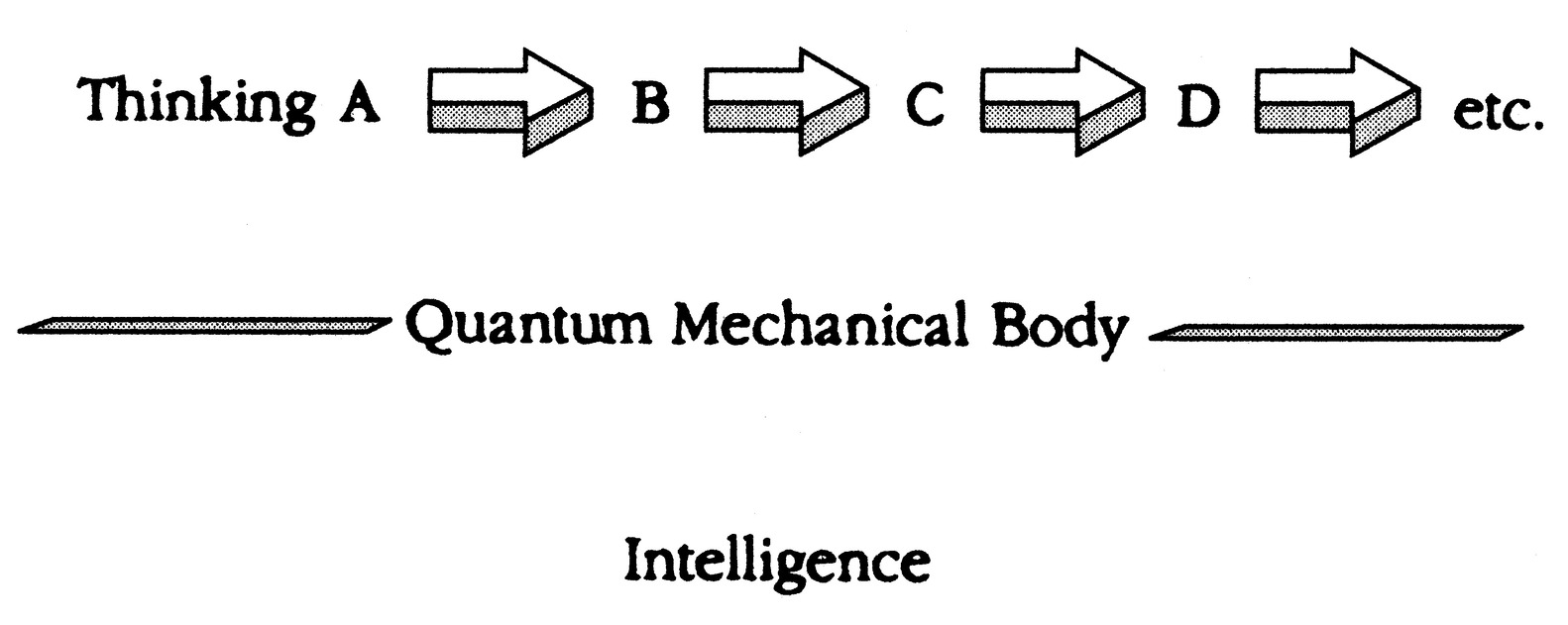

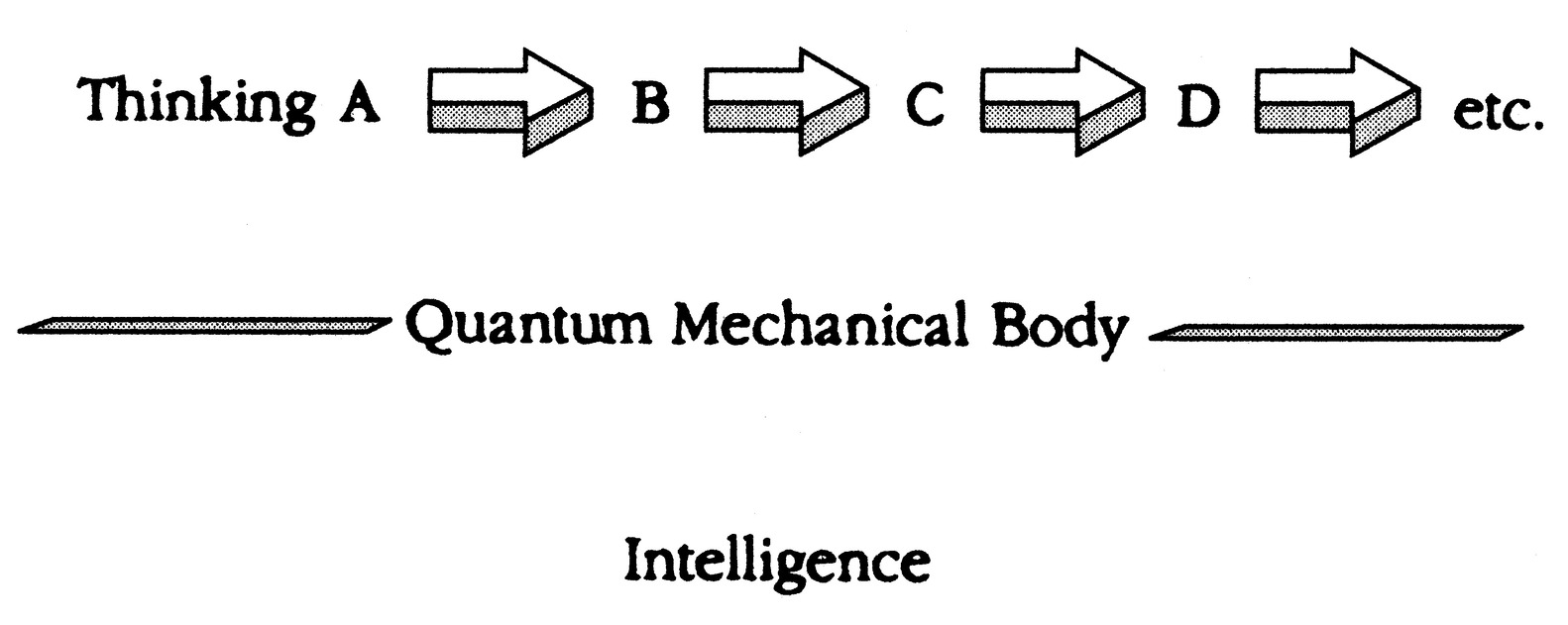

Above the line is a flow of thoughts that never ends, at least while we are awake. Thought is linked to thought without end. Our normal experience keeps within this range of ongoing events, which may be infinite on the horizontal axis yet quite shallow on the vertical. It is possible to spend a lifetime listening to the inventory of the mind without ever dipping into its source. Yet, touching the source is how the mind creates its patterns of intelligence. These patterns are at first only blueprints, but whatever they inscribe will hold—they will form our ideas and beliefs about reality.

The field of intelligence is extremely sensitive to change, however, both for good and ill. Two years ago I saw a woman in her thirties who came to Lancaster to be treated for breast cancer. Her condition was extremely serious, since the malignancy had metastasized to the bone marrow everywhere in her body. She suffered from constant pain in her bones as a result. After receiving the normal, and quite drastic, courses of radiation and chemotherapy from her doctor at home in Denver, she came to Boston for Ayurvedic treatments. She responded very well. After spending a week as an inpatient, her bone pain disappeared. She was not offered any promises about her cancer, but she went home in a state of renewed hope and optimism. Unfortunately, when she reported to her doctor that she had improved, he told her that it was all in her head—she had received no orthodox therapy that could have relieved her symptoms. Within a day her bone pain returned. She called me, feeling panicky, and I asked if she could return to Boston immediately. She did, and fortunately after another week her bone pain again receded.

Without intending to harm his patient—I am sure he wanted to be realistic in his appraisal—this woman’s doctor made a cruel mistake. He assumed that what is “in your head” is not real, or at least very inferior to the reality of cancer. Being trained in scientific methods, he knew the predictable outcomes of various kinds of malignancy, and when he saw an unexpected result, he tried to push it back into the range of the predictable. Doctors push patients into predictable results all the time, because medical-school training is focused entirely on the horizontal axis.

Making the links of cause and effect tighter and tighter is the whole motivation behind medical research. Our great-grandfathers vaguely knew that germs existed; we can anatomize thousands of specific viruses and bacteria, down to the tiniest amino-acid groups and beyond. Unfortunately, this leaves very little opening for any journey along the vertical axis, which might take one to a deeper reality.

A recent patient listed on his medical questionnaire that he “once had a brain tumor.” I asked him what that meant, and he told me this story: About five years ago, while living in Michigan, he began to have sudden dizzy spells. These quickly grew worse, and in a few weeks he was vomiting and had double vision, with increasing loss of balance and motor coordination. He went to a hospital, where a CAT scan was taken of his brain. The doctors informed him that the test had disclosed a shadowy mass in his forebrain larger than a lemon; in their opinion, he had a brain tumor. A tissue sample taken from the tumor revealed that indeed it was a deadly, rapidly growing cancer.

Because the tumor was so large and delicately placed, it was considered inoperable. The doctors recommended high doses of radiation and chemotherapy, without which the man would be dead in six months. The therapy would have severe side effects, nearly as bad as his present symptoms. Certain of these, such as nausea, headaches, and skin irritation, would be uncomfortable; others, such as the weakening of his immune system, could be deadly, since he would become prone to contracting other types of cancer in the future. There was also the definite possibility that he would be prey to anxiety and depression, which could be lasting. Even with maximum treatment to shrink the tumor, the prognosis for full recovery was not good, but it was better than nothing.

The patient could not accept this reasoning (although it is statistically quite sound). He moved to California and joined a meditation group; he practiced a whole series of diets, mental techniques, exercises, and visualizations. He encouraged in himself a totally positive attitude toward his condition. Thousands of cancer patients, as a rule from the best-educated groups, turn to such measures, which conventional medicine looks on as trying to buy false hope. In this case, however, the man began to feel better, and within six months his symptoms were almost completely gone. Hopeful but also anxious, he returned to Michigan and underwent another CAT scan. This one showed no traces of cancer and no sign that any had ever been present.

In response to this, his doctors informed him that he had not recovered from cancer, because they had never heard of such a recovery. In fact, they said, the original CAT scan was not his but another patient’s. They were sorry for the mistake, but from that moment on, they disavowed any involvement with his case. The patient was immensely relieved that his symptoms were gone, and he believes in the original CAT scan, which has his name and Social Security number on it. When I contacted the hospital to ask for his records, I was informed that he had never been treated there for cancer but had been mixed up with another brain-tumor patient.

All I can assume is that even with X rays and a biopsy, these doctors could not accept that a remission had occurred, for the simple reason that their experience told them it was impossible. One should never underestimate the power of indoctrination. Medical training is highly technical, specialized, and rigorous, but it came about just like any other human activity—by people collecting experiences and using those experiences to form explanations and patterns. These patterns in turn serve to indoctrinate the pattern makers, and within a very short period of time the indoctrination becomes law.

It is fascinating that a major study of four hundred spontaneous remissions of cancer, later interpreted by Elmer and Alyce Green of the Menninger Clinic, found that all the patients had only one thing in common—every person had changed his attitudes before the remission occurred, finding some way to become hopeful, courageous, and positive. In other words, they broke down their indoctrination (even if the doctors did not break down theirs). The mystery that clouds this otherwise clear finding has to do with causation. Did the remissions occur because of the new attitudes or parallel to them? Perhaps causation is too delicate to pinpoint in this case, being replaced by a general, holistic process of getting well in mind and body at the same time. The mind-body system, about to throw off the cancer, should know that the process is under way and may begin to generate much more positive thoughts simultaneously.

However it works, the key seems to be spontaneity. Channeling positive attitudes into oneself as a planned therapy has proved only haphazardly successful as a means of fighting disease. The positive input does not tend to go very deep. Consciousness is more pervasive than medicine gives it credit for. Even when it is ignored, however, the silent field of intelligence knows what is happening. It is, after all, intelligent. Its knowledge reaches beyond buffers and screens, going farther than we expect.

To illustrate: for decades, surgeons safely assumed that an anesthetized patient was unconscious and therefore not influenced by what happened in the operating room. Then it was discovered (by hypnotizing postoperative patients) that in fact the “unconscious” mind heard every word that was uttered during the procedure. When the surgeons said aloud that a condition was more serious than they had thought or had little chance of cure, the patients tended to play out those gloomy predictions by not recovering. As a result of these findings, which validate the idea of nocebo, it is now standard practice not to make negative remarks during surgery. The more positive the surgeon’s expressed opinions, in fact, the more positive the outcome for the patient.

It would be even better to use this highly sensitive, extremely powerful intelligence for the patient’s cure. The point of diving into the region of the quantum body is to change the blueprint itself, rather than to wait for symptoms on the surface, which will then have to be manipulated using medicine. The case of the woman with bone pain is a reminder that the buffer that keeps us so securely above the line, away from our deeper selves, is always made by us. It is therefore subject to revision at any time. We constantly build patterns of intelligence and look through them to tell us what is real. If we see pain, there is pain, but if we don’t, the pain will be gone.

Nature did not make us ignorant of our deeper selves. Anesthetized patients have known what was going on all along, presumably since the beginnings of modern surgery in the 1850s. The silent field of intelligence is out of reach by our choice, reinforced through generations of cultural bias. Sometimes a new reality forces itself to be recognized, and then things can shift. New patterns of intelligence arise; a deep transformation can then take place, but it is not essentially different from the mind-body transformations we have already been talking about.

Normal reality is like a spell—a very necessary one, since we must live by habits, routines, and codes that we take for granted. The problem arises when you can make the spell but not break it. If you could dive, this very minute, below your everyday reality to its source, you would certainly have a remarkable experience. The psychologist Abraham Maslow, who was a pioneer in studying the positive aspects of the human personality, gave a classic description of the experience of the deep self: “These moments were of pure, positive happiness, when all doubts, all fears, all inhibitions, all tensions, all weaknesses, were left behind. Now self-consciousness was lost. All separateness and distance from the world disappeared….”

Although such experiences are rare—Maslow termed them “peak experiences” for that reason—they have a curative power that goes far beyond their brief duration, which may be a few days or just a few hours. Maslow records that two of his patients, one a long-term depressive who had often considered suicide, the other a person who suffered from severe anxiety attacks, were both immediately and permanently cured after spontaneously falling into such experiences (for each it happened only once).

Maslow also talks about the reconciliation with life that people have realized through these moments: “They felt one with the world, fused with it, really belonging to it instead of being outside looking in. (One subject said, for instance, ‘I felt like a member of a family, not like an orphan.’)”

Any sudden revelation of a deeper reality carries enormous power with it—one taste alone can make life undeniably worthwhile. Maslow’s patients recognized this inner power as something quite outside the ordinary. It is not energy or strength, genius or insight, but it underlies all of these. It is life power in its purest form. Maslow’s understanding stopped short at the critical moment—he was never able actually to give anyone a peak experience—yet he was fascinated by these events that transcend normal life. In 1961, after several decades of writing and thinking about the subject, he concluded that it was indeed normal life and not the mystical that he had been observing:

“The little that I had ever read about mystic experiences tied them in with religion, with visions of the supernatural. And, like most scientists, I had sniffed at them in disbelief and considered it all nonsense, maybe hallucinations, maybe hysteria—almost surely pathological. But the people telling me about these experiences were not such people—they were the healthiest people!”

Because he detected these experiences in fewer than 1 percent of the population, Maslow viewed them as accidents or as moments of grace. I believe that they were glimpses into a field that underlies everyone’s life, but which has remained elusive. The implication is that we should dive very deep if we want to transcend normal reality. We are in search of an experience that will reshape the world.

Finding the silent gap that flashes in between our thoughts seems relatively easy, but because it flashes by, a tiny gap is not a doorway. The quantum body is not separate from us—it is us—yet we are not experiencing it right now. Sitting here, we are thinking, reading, talking, breathing, digesting, and so on, all of which happens above the line.

Here is an analogy that brings the quantum mechanical body into focus: Take a bar magnet and place a piece of paper over it. Next, sprinkle iron filings on the paper and jostle it slightly. What will emerge is a pattern of curving lines, one inside the other, that arch from the magnet’s north to south pole and back again. The overall design you have made represents a map of the magnetic lines of force that otherwise would be invisible, except that the iron particles automatically align themselves to bring out the image.

In this analogy, we see all mind-body activity above the paper and the hidden field of intelligence below. The iron filings moving around are mind-body activity, automatically aligning with the magnetic field, which is intelligence. The field is completely invisible and unknowable until it shows its hand by moving some bits of matter around. And the piece of paper? It is the quantum mechanical body, a thin screen that shows exactly what patterns of intelligence are being manifested at the moment.

There is more to this simple comparison than you might at first suppose. Without the paper to separate the two, the magnet and the iron could not interact in any orderly way. Try bringing a magnet close to some iron filings. Instead of forming regularly spaced lines, the filings simply clump shapelessly onto the magnet’s surface. With the paper in place, not only do you have an image of the magnetic field, but if you rotate the magnet you can watch the iron filings move to mirror the new field that has been created. If you didn’t know that there was a magnet, you would swear that the iron was alive, because it seems to move by itself. But it is really the hidden field that is generating these lifelike appearances.

There you have a true picture of how the bodymind actually relates to the field of intelligence. The two remain separated, but the division is invisible and has no thickness whatever. It is just a gap. The only way one knows that the quantum level even exists is that images and patterns keep cropping up everywhere in the body. Mysterious furrows run across the surface of the brain; beautiful swirls, exactly like the center of a sunflower, show up in molecules of DNA; the inside of the femur contains marvelous webs of bone tissue, like the intricate supports of a cantilever bridge.

Wherever you look, there is no chaos, and that is the strongest proof of all that there really is a hidden physiology. Intelligence turns chaos into patterns. There is incredible chaos implied in the idea of having to process billions of chemical messages every minute, yet in reality, the complexity of the mind-body system is misleading: what emerges from our brains are coherent images, just as a coherent newspaper photograph emerges from thousands of scattered dots. The matter in our bodies never disintegrates into a shapeless, mindless pile—until the moment of death. In answer to the obvious question, “Where is this quantum mechanical body, anyway?” one can now confidently answer that it lies in a gap that unfortunately is rather difficult to picture, since it is silent, has no thickness, and exists everywhere.

To dive into the field of intelligence appears easy now: it requires only a trip across a gap. But even though the gap has no thickness, it forms a barrier no steel door could possibly match. We can simplify our diagram to show what has happened to make the journey so difficult:

The whole story is contained in the difference between active and silent intelligence. We have confirmed that this difference is very real. DNA can be active or silent; our thoughts can be expressed or stored away in drawers of silence; we can be awake or asleep. All these changes require a journey across the gap, but not a conscious journey. To see what sleep is like, you would have to stay awake, which is impossible. If you want to see the difference between active and dormant DNA, you cannot find it in any chemical bond, since the two DNAs are physically identical. And so on and on for all the transformations of mind and body.

The same difficulty holds true in physics—a photon is a form of light, as is a light wave, but both arise from a hidden field. On the surface of reality we see either photons or light waves, but the reason why both can exist in one reality is that they preexist as mere possibilities in the quantum field. Who has ever photographed a possibility? Yet, that is all the quantum world is made of. If you say a word or make a molecule, you have chosen to act. A little wave laps up from the ocean’s surface, becoming an incident in the space-time world. The whole ocean remains behind, a vast, silent reservoir of possibilities, of waves that have yet to be born.

As they dance around on the paper, the iron filings might look at one another and say, “Well, this is life, let’s look into its mysteries.” Deciding to do that, they can begin a thought-adventure of the kind we call science. No matter how adventurous their thoughts become, they will never cross the gap. The gap is a one-way door, as far as thinking goes, and that is its true mystery.

From a certain perspective, the whole idea that we are outcroppings from an invisible, infinite field seems ridiculous. A man’s body is a packet of flesh and bones occupying a few cubic feet of space; his mind is an amazingly intricate but finite mechanism filled with a set number of conceptions; his society is a grossly imperfect organization bound to a history of ignorance and conflict.

These obvious facts have never settled the issue, strangely enough. We trust our finite everyday experiences, which are good enough for driving a car, earning a living, and going to the beach, but they are not quite convincing enough compared to the overwhelming experience of the infinite. That experience, repeated throughout the centuries, causes some people to suspect that reality is very different, and far vaster, than what the mind, the body, and society generally accept.

Einstein himself experienced this reality. He has testified to moments when “one feels free from one’s own identification with human limitation”:

“At such moments one imagines that one stands on some spot of a small planet gazing in amazement at the cold and yet profoundly moving beauty of the eternal, the unfathomable. Life and death flow into one, and there is neither evolution nor destiny, only Being.”

Although this sounds like a spiritual insight (and Einstein considered himself deeply spiritual), it is really a glimpse into a level of our own consciousness that can be mapped and explored. Without having any control over their awareness or any cogent explanation for what is happening, people sense that the state of rapt silence is not simply emptiness. The great traditions of wisdom have largely been founded by one or a few individuals who realized the universe through themselves. To solve the mystery of the gap, we need to consult the ones who have been there; if they have found a real world, then there will be new Einsteins to follow, and they will be Einsteins of consciousness.

EXPANDING THE TOPIC

The wisdom of the body comes from two places—active intelligence and silent intelligence. Self-care is an example of active intelligence. You listen to your body. You heed its signals of pain and discomfort. You take steps to maintain a state of wellbeing. Active intelligence stretches no one’s imagination. Silent intelligence is different, because being invisible, it can only be located in the gap. Yet of the two kinds of intelligence, the kind that works in silence is infinitely wiser.

When Quantum Healing first appeared, it was almost impossible to get mainstream doctors even to entertain such a notion as “the wisdom of the body.” I found refuge in the mystical poets, who became almost constant companions. They knew about the hidden dimensions of existence. Here is a verse from Rumi, the illuminated Persian poet:

What do I long for?

Something that is felt in the night

But not seen in the day.

In a rational age, poetic intimations aren’t enough. Yet poets can think, too, as when Rabindranath Tagore, the great Bengali poet, contemplates how a full-blown rose opens from a bud. He sees at work the same silent intelligence I was describing in the human body.

He who can open a bud does it simply

One glance, and the sap must stir,

One breath, and a flower flutters in the wind,

Colors flash out like longings of the heart,

And perfume betrays sweet secrets.

He who can open a bud does it simply.

Who could put it more beautifully? Instead of saying “He who can open a bud,” why not “She who can bring a child into the world”? Silent intelligence is simple, spontaneous, and a part of us.

As it turned out, I was lucky to be writing when I was. Hard research was just uncovering the receptor sites on the cell membrane, the “plug-ins” for messages from the brain. One found exactly the same receptor sites everywhere. The immune system therefore became known as a floating brain, and science had an explanation for gut instincts—tissues remote from the brain were thinking, too, in a chemical language.

Yet the lifestyle advice that looks so promising for healing the mind-body connection doesn’t really penetrate into the quantum domain. It remains in the domain of active intelligence. We have to be a bit careful here. If you change your diet, new messages will be sent to the cells of the digestive tract, and from there the messaging throughout the body is altered (which is why, for example, you fall asleep after eating too much at Thanksgiving). Because all messages are produced in the gap, there is a quantum dimension to every process in the body.

What’s lacking is a direct telephone line, so that you can speak to your own silent intelligence and hear what it says in return. A direct line is opened through “second attention.” With first attention you live your life in the world—working, eating, sleeping, relating. With second attention you peer into the invisible domain that creates, governs, and regulates the flow of life. Let’s call silent intelligence X, because it cannot be labeled or named. Labels belong to things, not to processes. What is X doing from its invisible station behind the scene? Its range of activity is quite astonishing:

It takes each tiny event and weaves it into the tapestry of life.

It gives meaning and purpose to everything you experience.

It guides every action to its highest and best use.

It breathes love into being.

It favors evolution and progress.

It promotes those outcomes that are the most life supporting.

If this sounds like a mystical laundry list, consider the beating of a single heart cell. It meshes with every other heart cell in perfect sync. It registers love, pain, hope, fear, and every other emotion. It tells you without a doubt that you are in love. It settles into wise contentment as you mature. It looks out for the health of the entire body. I’ve used slightly metaphorical language, but a cell biologist could identify the receptor sites and messaging paths that connect brain and heart so completely that every function I’ve mentioned has a physiological basis.

The deeper point, however, is that every cell, all five trillion or so, depends upon silent intelligence to keep itself—and you—together. Intelligence is what prevents the living structures in the body from flying apart into a cloud of atoms. Such intelligence is far from incidental. As in the piano metaphor I find myself returning to, a piano doesn’t make the music that comes out of it; a mind does. When a cell communicates with other cells, there is no message in the chemicals that carry the message until the mind puts one inside.

Second attention opens the lines of communication so that any impulse—love, compassion, empathy, appreciation, insight, intuition, imagination—is evolutionary and life supporting. Here we must look beyond science, because to a cell biologist, chemicals are chemicals. They are value neutral. An impulse of hatred can be encoded as easily as an impulse of love. But if you stand back and examine your life from the perspective of second attention, you can see value everywhere in the body. Cells cooperate with one another. They understand that the good of the whole body is paramount. They live in the present moment and base their lives on trusting that nourishment will always come to them. They know how to self-heal.

Second attention promotes these values, not by analyzing the activity of cells but by going to the source, from which life is sustained. Since writing Quantum Healing, I’ve become even more convinced that consciousness holds the key to the flow of life whether you define life scientifically, mystically, or through any other label. While we argue over labels, we are missing the opportunity to promote the silent intelligence that is crucial to everything.

A practical-minded reader will say, “Fine, but what do I do?” Beyond making the positive lifestyle changes that have become well-known, there are more subtle actions to perform. These are mental actions, but they aren’t the same as positive thinking, therapy, or even self-awareness. They focus instead on attention and intention. When you have an intention to move your hand, there are no steps to go through. The instant you want to move your hand, it moves. But what about the intention to heal yourself or the intention to promote peace in your surroundings?

Science finds itself skeptical and largely baffled when such questions come up—they are barely considered legitimate. Yet on the fringes of respectability there are mounting research studies on the power of prayer to help the sick. Since Quantum Healing appeared, other studies have gone even deeper into the effectiveness of intention. Especially intriguing is a pioneering study of native Hawaiian healers led by the late Dr. Jeanne Achterberg, a physiologist of the mind-body connection who was fascinated by anecdotes that native healers often did their work from a distance. Here’s how the Achterberg study worked, as described in Super Brain, which I wrote with Rudolph E. Tanzi.

In 2005, after a two-year search, she and her colleagues gathered eleven Hawaiian healers. Each had pursued their native healing tradition for an average of 23 years. The healers were asked to select a person with whom they had successfully worked in the past and with whom they felt an empathic connection. This person would be the recipient of healing in a controlled setting. The healers described their methods in a variety of ways—as prayer, sending energy, good intentions, or simply thinking and wishing the highest good for their subjects. Achterberg simply called these efforts distant intentionality (DI).

Each recipient was isolated from the healer while undergoing an fMRI of their brain activity. The healers were asked to randomly send DI at two-minute intervals; the recipients could not have anticipated when the DI was being sent. Yet their brains did. Significant differences were found between the experimental (send) periods and control (no-send) periods in ten out of eleven cases. For the send periods, specific areas within the subjects’ brains “lit up” on the fMRI scan, indicating increased metabolic activity. This did not occur during the no-send periods.

Skeptics dismiss such studies without actually trying to duplicate them or to understand the hidden mechanics of intention. However, in the Vedic tradition, there has been a sophisticated description of the mechanics of intention going back centuries. It was divided into three parts. First, an effective intention must arise in a deep level of the mind, below the stream of constant activity. The very deepest state of awareness, which is calm, still, unmoved, and all-wise, is known in Sanskrit as samadhi.

What Helps Samadhi

• Meditation

• Calm, peaceful surroundings

• Lack of mental agitation

• Absence of stress

• Minimal distractions

• Self-acceptance

• Self-awareness

What Hurts Samadhi

The opposite of the above: anything that jangles the mind, making it restless, overactive, stressed, and outward gazing

The second part of the mechanics of intention is to have the intention be as clear and focused as possible. This gives awareness a specific direction. The term for this in Sanskrit is dharana.

What Helps Dharana

• Clear thinking

• Acting purposefully

• Not losing sight of the goal

• Confidence

• The ability to stick with a mental task

• Follow-through

• Diligence

What Hurts Dharana

• Multitasking

• Mental confusion

• Conflicted desires

• Lack of self-knowledge

• Fantasy and daydreaming

• Short attention span

• A craving to escape the self

The third part of the mechanics of intention is a state of flexibility where your mind is steady and active at the same time. You can see this state when a child is totally engrossed in playing with a toy. His attention is on nothing else, and yet inside the play, he does all kinds of things (pushing a toy truck, throwing finger paint on the walls). When you have an intention, your focus is sharp, but then you let go and allow silent intelligence to take care of the outcome. This isn’t the same as passive indifference. You are open and alert, because there can be any response at all. The term in Sanskrit for this is dhyana.

What Helps Dhyana

• Being relaxed and easy

• Mindfulness

• Acceptance of things as they are

• Putting a value on being

• Trust

• Believing in the wisdom of uncertainty

• Allegiance to a higher level of intelligence that organizes reality

What Hurts Dhyana

• Tension

• Anticipation

• Controlling yourself and others

• Rigidity

• Insistence on rules and routines

• Obsession

• Compulsive behavior

• Inability to believe that the universe supports you

I’ve gone into detail here because at the time of Quantum Healing, there were few action steps that pertained to silent intelligence other than meditation, which remains the most powerful and direct means to connect with the mind’s deeper levels. But meditation too often lacks a purposeful component. The toolbox is opened and the tools just lie there. That’s why it’s important to master the mechanics of intention. The paradox is that there’s nothing really to do and yet everything to do. There’s nothing to do as far as first attention is concerned. You live your life, dealing with its challenges as best you can.

At the level of second attention, however, there’s everything to do, because you are calling upon the universe, to use a popular phrase, and activating hidden forces unknown to the outward-looking mind. A now-obscure Scottish writer and mountaineer, W. H. Murray, hit upon the mechanics of intention with uncanny precision, intuiting the same things that the Vedic sages described.

There is one elementary truth, the ignorance of which kills countless ideas and splendid plans; that the moment one definitely commits oneself, then providence moves too.

Having discovered the connection between what happens “in here” (intention) and what happens “out there” (the forces that an intention can move), Murray saw that these awakened forces exist to support human aspirations.

All sorts of things occur to help one that would never otherwise have occurred. A whole stream of events issues from the decision raising in one’s favor all manner of unforeseen events, meetings and material assistance which no one could have dreamed would have come their way.

For quantum healing to be completely viable, the power of intention must be harnessed, calling not upon “providence,” which many people don’t accept, but upon the inner intelligence that more and more scientific evidence supports. That the mind can move molecules is just as wondrous as faith moving mountains.