1939—1945

THE DEADLIEST CONFLICT IN HUMAN HISTORY WAS FOUGHT BY SOLDIERS FROM EVERY PART OF THE WORLD IN THE SERVICE OF THE ALLIED OR AXIS POWERS AND ENDED WITH THE RISE OF TWO GREAT POSTWAR SUPERPOWERS, THE UNITED STATES AND THE SOVIET UNION.

After the end of World War I, many millions of Germans were left in a state of smoldering resentment by the harsh terms of the Treaty of Versailles. The Great Depression of the 1930s was exacerbated in Germany by the billions of dollars of war reparations owed, as well as by the fact that large portions of its territory had been taken away. Germany, with a population of 65 million, was also forbidden to have a large standing army, but during the Weimar Republic that governed Germany immediately after the war, secret armed paramilitary groups had arisen. When Adolf Hitler took power in 1933, these powerful groups (the Sturmabetilung, or SA, and the Schutzstaffel, or SS) became the nucleus of the new German army.

Hitler led the German National Socialist, or Nazi, Party, which is to say he was a fascist. Essentially, he preached the message that Germany needed to push its boundaries outward to accommodate its expanding population, and thus wars for territory needed to be fought. Further, a demographic restructuring of Germany along racial lines was essential—all those races, in particular the Jews, which were deemed “impure” or “undesirable” would be (it was soon clear) liquidated, particularly if they lived in territory that Germans desired to possess.

To this end, Hitler stepped up German rearmament throughout the 1930s, ignoring the ineffectual protests of the governments of countries such as France and Great Britain, which were themselves mired in economic difficulties because of the Great Depression. These countries (and the equally ineffectual League of Nations, which was the precursor to the United Nations) did nothing when Hitler sent an army into the Rhineland (a zone along the French-German border demilitarized after World War I) in 1936, and in 1938 annexed Austria, and took control of the Sudetenland, a Czechoslovakian region of German-speaking people.

In the latter case, British Prime Minister Neville Chamberlain acquiesced to Hitler’s demands, in return for an agreement that he would not move into the rest of Czechoslovakia. Chamberlain came back home to Great Britain announcing “peace in our time,” but within six months Hitler had annexed the rest of Czechoslovakia. Within a year, on September 1, 1939, the date traditionally given as the beginning of World War II, Hitler had begun his invasion of Poland. (Hitler intended to invade the Soviet Union, but he had for the time being signed a nonaggression pact with Soviet leader Joseph Stalin, agreeing to divide up Poland.)

Hitler’s rapid assault on Poland—with Stuka dive bombers, tanks, and infantry—was the very first blitzkrieg, or “lightning war.” France and Germany were bound by treaty to help Poland and thus declared war against Germany on September 3, 1939. The following April, Hitler’s mechanized legions invaded Norway, and in May they attacked Holland, Belgium, and France. The French army was utterly defeated, and a British expeditionary force sent to help was driven back to the English Channel coast, where it was evacuated at Dunkirk.

In the meantime, in the Far East, the Japanese were pursuing a policy of expansion as well. They had invaded and seized Manchuria from the Chinese in 1937, and they were engaged in a continuing war with China. Border skirmishes with the Red Army in western Manchuria proved the Russians a tougher nut to crack than they were during the Russo-Japanese War.

The Japanese turned their attentions south, planning an invasion of oil-rich Southeast Asia. The United States—owned Philippines stood in their way, and Japanese war planners knew that they would sooner or later have to attack the United States. Seeing the string of German victories, the Japanese reached a mutual defense agreement with Germany and Italy, which was ruled by Benito Mussolini. This Tripartite Pact established the Berlin—Rome—Tokyo Axis, and Germany, Italy, and Japan became known as the Axis Powers.

Beginning in August 1940, Hermann Göring, the head of Germany’s powerful Luftwaffe, launched a massive bombing campaign against England, beginning with Royal Air Force bases (RAF), to soften up England prior to a German invasion. The RAF suffered horrendous losses, but it held out. (During one two-week period, one in four English pilots was killed.) The Germans then switched tactics, bombing British cities in terror bombings. but the British, led by their resolute prime minister, Winston Churchill, refused to give up. German victories in Greece and the Balkans made 1940 a victorious year for the Axis.

By the spring of 1941, however, as Great Britain suffered devastating bombing as well as a German submarine naval blockade, the country’s situation was dire. But in March of that year, the United States, officially neutral, passed Lend-Lease legislation that allowed it to send war material to countries whose security affected its own. Massive supplies were sent in convoys to Great Britain through the perilous North Atlantic seas, which were infested with German U-Boats.

Great Britain’s situation became somewhat better when Hitler made the huge blunder of attacking the Soviet Union in June 1941 with a force of a 1.5 million soldiers. Caught at first by surprise, the Soviets reeled back, losing some 3 million soldiers—dead, wounded, and captured—before the Soviet line stabilized and the Russian winter set the Germans back.

On December 7, 1941, Japan launched a surprise aerial attack on the U.S. naval base of Pearl Harbor, Hawaii. Devastating though it was, the attack—devised by Admiral Isoruku Yamamoto—missed the United States’ aircraft carriers, which were out at sea, and thus was only a limited tactical success. The United States quickly declared war against the Axis Powers.

In the Far East, the Japanese attacked and captured the Philippines, Burma, Malaya, the Dutch East Indies, and Singapore by April 1942 and occupied numerous South Pacific islands. But an attempt to capture Port Moresby, New Guinea, and thus cut off communications between the United States and Australia failed when the Americans turned back and destroyed the Japanese invasion force at the Battle of the Coral Sea in May 1942. A month later, an attempt to destroy the U.S. fleet was thwarted at the Battle of Midway when the carrier-based airplanes of the U.S. Navy sank four Japanese aircraft carriers, and the Americans began to turn the tide against the Japanese in the Pacific.

In May 1942, an offensive by the famed German Afrika Korps, under General Erwin Rommel had driven the defending British forces in Libya nearly back to Cairo, but then British resistance stiffened and they stopped the Germans in two battles at El Alamein, in July and October 1942. A month later, British and U.S. troops (commanded by General Dwight D. Eisenhower) landed in Morocco at the rear of the Germans and caught them in a pincer. German troops in Africa were forced to surrender in May 1943. With their southern flanks secure, the allies invaded Sicily in July and Italy in September.

Another blow to the Germans came with their stalled attack on the Russian city of Stalingrad. The German offensive had picked up steam since the winter of 1941—42, and they attacked Stalingrad in August 1942. But unexpectedly tough resistance from the Russians turned the battle for the city into an epic bloodbath in which 400,000 Germans would lose their lives and an entire German army would surrender within four months’ time, forever blunting Hitler’s invasion.

In the meantime, in the Pacific, U.S. war planners had decided upon a two-prong offensive against the Japanese. One arm of the offensive, based in Australia, would attack up the New Guinea coast, through the Solomon Islands, and on to the Philippines and Tokyo, bypassing and cutting off numerous Japanese-held islands along the way. The other offensive arm would thrust along some of the smaller islands of the Central Pacific, to the Marianas, the Philippines, and the Chinese coast, and from there to the Japanese home islands. This latter strategy made it crucial to keep the Nationalist Chinese government in the war, to protect the United States’ left flank. Masses of arms and material were sent to Chiang Kai-shek’s armies, which even so barely held their own against the Japanese.

The U.S. “island-hopping” began with an attack on the Japanese-held Solomon Island of Guadalcanal in August 1942, where a hard-fought six-month battle ended in U.S. victory in February 1943. In the meantime, U.S. Marines fought battles at coral atolls such as Tarawa, Peleliu, and Bougainville, building bomber bases as they went. By November 1944, B-29 bombers operating out of airfields in the northern Marianas and China were able to reach targets in Japan.

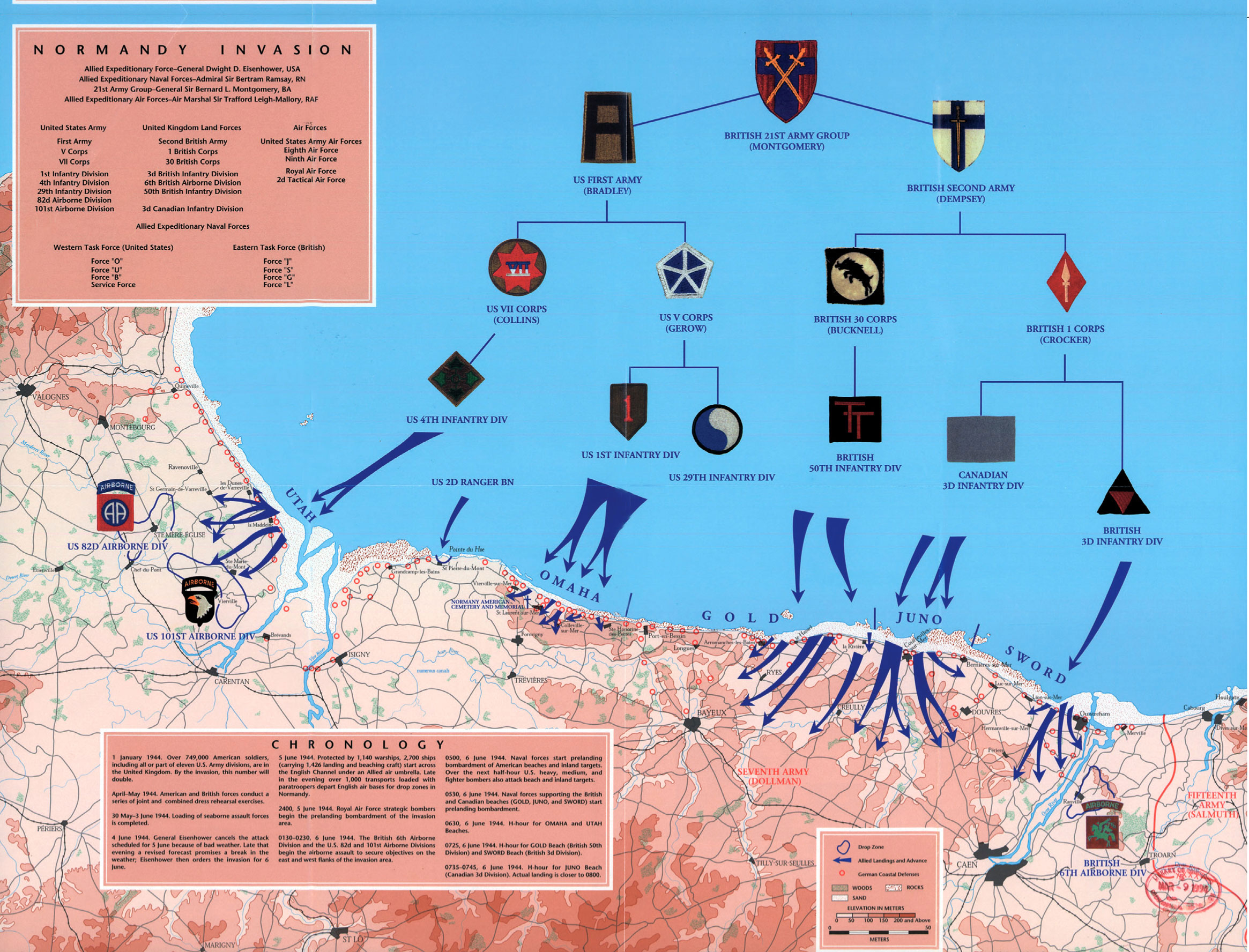

After much debate, the allies finally decided to invade France along the Normandy coast on June 6, 1944. With an armada of 6,000 ships containing an attacking force of 175,000 British, Canadian, and U.S. troops, the allies won a hard-fought toe-hold in France. After bloody fighting during the summer months, the allies were able to drive the Germans into full-blown retreat that August.

THE GERMAN OFFENSIVE ATTACKED STALINGRAD IN AUGUST 1942. BUT UNEXPECTEDLY TOUGH RESISTANCE FROM THE RUSSIANS TURNED THE BATTLE FOR THE CITY INTO AN EPIC BLOODBATH IN WHICH 400,000 GERMANS WOULD LOSE THEIR LIVES.

However, the Germans were far from down yet. In December 1944, secretly assembling some 250,000 troops and 1,000 tanks, they launched the Battle of the Bulge in the Ardennes Forest in Belgium, very nearly breaking through U.S. and British lines. Despite a fierce struggle, they were thrown back, and the allies continued their march toward Berlin, using powerful bombers to destroy German cities, factories, and troops. All the while, the victorious Soviet Army pushed the Germans back from the east. After Hitler committed suicide in his Berlin bunker, Germany surrendered on May 7, 1945.

This left the allies free to concentrate all their might on the Japanese. U.S. air raids over Japan increased in intensity, targeting civilian populations. U.S. Marines island-hopped right to Japan’s Bonin (Iwo Jima) and Ryukyus (Okinawa) islands by April 1945, but Japanese resistance had become even more ferocious as their homeland was invaded, especially with the introduction of the kamikaze, or suicide, pilot.

Fearful of the casualties that would ensue if the Americans and British invaded Japan as planned that November, the new U.S. President Harry S. Truman opted to drop the newly developed atomic bomb on Japan. The first bomb was dropped on Hiroshima on August 6, 1945. Three days later, another bomb was dropped on Nagasaki. With 200,000 dead from these two bombs alone, the Japanese capitulated. On September 2, 1945, aboard the U.S. battleship USS Missouri, the Japanese signed the surrender agreement that ended World War II.

After the war, the United Nations was formed in the hopes of keeping peace, but no one was able to say with equanimity that the war to end all wars had been fought. World War II, with its millions of dead, had simply been too awful. The immediate result of the war was the elevation of the United States and the Soviet Union to superpower status, where they almost immediately squared off in the Cold War, each threatening the other with potential nuclear annihilation.

The colonial world order was now gone forever, with countries vying for self-determination. The discovery that Hitler had perpetuated the Holocaust in which more than 6 million Jews were killed in concentration camps changed how people everywhere viewed the notion of evil. It also helped hurry the state of Israel into existence.

D-Day: June 6, 1944

As the huge flotilla crossed the dark, choppy waters of the English Channel, the roar of protecting planes overhead, reporters in the holds of ships with the troops of the different Allied countries—the Americans, British, and Canadians—noticed an interesting phenomenon take shape. Most of the U.S. soldiers were green recruits who had never seen combat before. Normally one might expect these to be the most nervous, but in fact these young GIs appeared to be the coolest, almost glad to be taking part in history. They were, after all, about to make the first assault on Fortress Europa, Hitler’s territory since 1940, and strike right at the heart of the German empire.

The GIs laughed, cleaned their rifles, and sharpened their bayonets. They knew there was a tough task ahead and that some of them would die, but they all thought that someone would be someone else.

It was a different picture with the British and Canadian battalions that had seen three years or more of warfare. In their case, as one observer wrote, “Everybody who was any good had been promoted or become a casualty.” These men had faced Hitler’s Wehrmacht, his proud and combative infantry, and they knew how fiercely they could fight, especially now, defending their own territory. As the sky lightened—but did not clear—on this overcast early morning of June 6, 1944, these men knew just what was in store for them. They did not kid themselves that they, personally, would be the targets of a hailstorm of death and destruction.

THE JUNE 6, 1944, LANDING OF THE ALLIES ON THE BEACHES OF NORMANDY IS SHOWN IN THIS U.S. ARMY CENTER OF MILITARY HISTORY MAP. THE BEACHES INVADED WERE SWORD, JUNO, GOLD, OMAHA, AND UTAH, WITH THE FIRST THREE ATTACKED BY CANADIAN AND BRITISH FORCES AND THE LAST TWO BY THE AMERICANS. ALL TOTAL, ABOUT 10,000 MEN OUT OF 155,000 WERE KILLED OR WOUNDED DURING THE INVASION.

Green recruit or veteran, the hopes of the allies rested on these 150,000 men who were approaching 60 miles (97 km) of French coastline in some 6,500 ships. Despite the fact that the might of the world was stacked against Hitler, he was proving remarkably difficult to finally beat. In Italy, Allied forces were pushing up through the peninsula, but at a glacial pace over rugged terrain. Meanwhile, in Russia, the Soviets were also winning victories, but the German troops were giving way slowly. Nightly, Allied forces pounded German cities and industry, and yet the Germans kept on fighting.

Everyone, Germans or allies, knew that there would be a major invasion somewhere along the channel coast. The Germans defenses stretched all the way from Scandinavia to Spain, but they could not possibly fortify all areas equally. Their war planners had come to the conclusion that the Allies would attack across the Straits of Dover, heading for the Pas de Calais, the area of France closest to England. Calais had a natural harbor that the Allies could use. It made so much sense to the Germans that they stationed their main reserve—the Fifteenth Army, containing about 100,000 men—there.

It was not that the rest of the Atlantic Wall, as the Germans called it, was poorly fortified. Field Marshal Erwin Rommel—the famed Desert Fox—had been given charge of building up the defenses and was determined not to let the Allies get a foothold in France. He was certain that they would exploit any foothold with their massive advantage in armor and bombers.

Allied war planners—knowing from their top secret Ultra intercepts that the Germans were massing around Pas de Calais—had no intention of attacking there. The allies did stage a massive and elaborate deception to make the Germans think that an attack on Calais was imminent. However, the real target of Allied leaders, such as General Dwight D. Eisenhower, commander of Supreme Headquarters Allied Expeditionary Force, and General Bernard Law Montgomery, head of Allied ground forces, was Normandy, France. Here, specifically at the Cotentin Peninsula, on five beaches designed Juno, Gold, Sword, Utah, and Omaha, the beginning of the end of World War II would begin in an attack aptly named Operation Overlord.

As the Allied troops fought off seasickness and climbed down into their landing boats, bobbing up and down in the heavy chop of the English Channel, they watched a preparatory bombardment of the enemy positions. It was an awesome sight. Thousands of planes flew overhead, dropping bombs that turned the coastline into a curtain of smoke. Heavy booming thuds echoed back across the water, the footsteps of a thousand giants. The Allied air force had full ownership of the sky, with barely 200 Luftwaffe planes to oppose them.

Unbeknownst to those soldiers on the boats, the land battle for Normandy had begun the night before, when 20,000 men of the U.S. 82nd and 101st Airborne Divisions and the British Sixth Airborne had been dropped by parachute behind enemy lines. Their goal was to block off approaches to the Normandy beaches to keep the Germans from reinforcing them. But most of the jumpers went astray in the inevitable confusion of a combat parachute drop in darkness, and only one in twenty-five paratroopers landed in his assigned drop zone. Nevertheless, the chaos served its purpose, keeping the Germans guessing about what was coming. Many German commanders dismissed the disorganized paratrooper attacks as just another commando raid, even after one German general was ambushed and killed by 101st Airborne troopers who happened upon his staff car.

But there was a moment, as the sky brightened but just before the Allied bombers swept in, that the German gunners in their pillboxes on the shore could see exactly what was happening. Spread out on the waters before them was the largest flotilla the world had ever known. Then the bombers came, and the gunners put their heads down.

When the gunners manned their machine guns again, troops in landing craft were nearing the shore.

The beaches being invaded were, from east to west, Sword, Juno, Gold, Omaha, and Utah. The first three were attacked by Canadian and British forces, and the last two were attacked by Americans. On Sword Beach, the British, although confronted with minefields and beach obstacles, managed to land 28,000 troops with only 600 casualties and push to within a few miles of their objective, the town of Caen.

What happened on Juno Beach depended on what part of the beach you landed on and when you landed on it. In the first wave on Juno, Canadian casualties were nearly 50 percent, but in other areas of the beach where resistance was not so stiff, the allies made it ashore almost unopposed.

On Gold Beach, however, the British took extremely heavy casualties. Their landing craft lowered their ramps in 6 feet (1.8 m) of water, and numerous soldiers, weighed down by heavy equipment, drowned. Other soldiers got to the beach, only to face withering fire and an unreal scene of chaos. As one soldier remembered: “The beach was strewn with wreckage, a blazing tank, bundles of blanket and kit, bodies and bits of bodies. One bloke near me was blown in half by a shell, and his lower half collapsed in a bloody heap on the sand.”

On Utah Beach, mass confusion reigned. Stiff currents had carried the U.S. Fourth Division almost 2 miles (3 km) from where it was supposed to be, and the troops had no idea where they were. However, this turned out to be a stroke of luck, because they had landed in an area that was not quite so heavily defended. They managed to quickly break through the seawall and link up with paratroopers from the 101st Airborne.

It was on Omaha Beach that the slaughter truly reached epic proportions. Because the beach there was the only stretch of open sand in either direction for some miles, the German planners knew that the Allies would have to make use of it.

Omaha Beach is only 6 miles (9 km) long and about 400 yards (365 m) deep at low tide, which it was when the invasion was taking place. Much of the beach was shingle or shale, and there were high bluffs facing it in the front and on either side, making it a kind of natural amphitheater. German defenses here were formidable. Every inch of the beach was pre-sighted by machine guns, mortars, artillery, and underground ammunition chambers and pillboxes at the top of the cliffs, which were connected by a series of well-dug trenches. Five small ravines led up the cliffs, but at the top of each was an 88, the ubiquitous, and deadly, German light artillery gun of choice.

The minute U.S. soldiers landed here at about 6:40 a.m., the German defenders opened fire. The Germans were amazed at the Americans’ audacity. “They must be crazy,” one of them said to one of his comrades. “Are they going to swim ashore right under our muzzles?” The first landing craft on the beach simply disappeared in a hail of fire. Other GIs crawled up the beach, hiding in long snaking lines behind beach obstacles, while the machine guns raked up and down, like deadly garden hoses. (One German gunner would fire 12,000 rounds that day.) Finally, the Americans, urged on by brave noncoms and officers, realized that if they stayed where they were, they would die. And so they began to move forward, singly, in ones and twos, until they reached the comparative shelter of a seawall near the base of the cliff. By afternoon, a few men had made it up the draws, and more followed.

Ultimately, 40,000 men would land at Omaha Beach during the course of the day and spread out for about a mile from the top of the cliffs, where they dug in—as forces were digging in all up and down the 60-mile (97-km) stretch of Normandy beaches—waiting for the inevitable German counterattack.

The counterattack might have been inevitable, but it never came. German commanders thought that the real objective of the Allied attack was still the Pas de Calais, and that Normandy was just a diversion. It would take German commanders weeks to figure out otherwise, and by that time the allies had secured a firm beachhead 120 miles (193 km) long and 10 miles (16 km) deep, while more men and material poured into the man-made harbors that the Allies created in Normandy.

All told, about 10,000 men were killed or wounded out of a total of about 155,000 on D-Day, but this high price meant the final destruction of Hitler’s Germany. A lot of hard fighting still lay ahead, but the first major step had been taken.

The three men were in all their power and glory—Winston Churchill, cigar in hand, Franklin Delano Roosevelt, cape thrown over his shoulders, and Joseph Stalin, in military uniform—when they met in February 1945, at Yalta, in the Crimea to decide the fate of the postwar world.

Each had been instrumental in helping bring the defeat of the Axis Powers closer and closer to reality. Churchill was prime minister of Great Britain, replacing Neville Chamberlain, who had appeased Hitler and his Nazis and thus lost all credibility with the people of Great Britain. Churchill knew that he needed to provide inspiration for Great Britain to continue against the odds. His speeches during the dark days of the summer and fall of 1940 resounded with powerful inspiring language, as in his “finest hour” speech to the British parliament, where he declared that the Battle for Britain had begun. He said: “If the British Empire and its Commonwealth last for a thousand years, men will say, ‘This was their finest hour.’”

President Franklin Delano Roosevelt, who had ably led his country through the Great Depression, also began to subtly steer the United States toward war, despite numerous isolationists who thought that the United States should not interfere in what was going on in Europe. But Roosevelt, through Lend-Lease legislation, was able to provide aid to Great Britain. Then, when the Japanese attacked Pearl Harbor, Roosevelt declared war with the ringing words: “December 7, 1941…was a day which will live in infamy.” He, like Churchill, presided over a country that saw defeats in the early days of the war but that found its war footing very quickly and accepted rationing and other forms of privation on the civilian front so that the military might make greater strides against Germany, Italy, and Japan.

PICTURED: THE BIG THREE AT THE YALTA CONFERENCE IN THE CRIMEA REPRESENTED THE THREE MAJOR WORLD POWERS AT THE WAR’S CONCLUSION.

Getty Images

Premier Joseph Stalin was a different case. He was the totalitarian dictator of a country whose citizens he had ruthlessly purged (or starved because of his agricultural collectivization) by the millions. And he had been fooled into thinking that Hitler was his ally early in the war. Nevertheless, as Russians reeled back under the initial onslaught of Operation Barbarossa, Hitler’s massive attack on Russia, Stalin, too, provided the backbone that kept his country from capitulating.

At Yalta, these three leaders came together to decide what would happen after Germany and Japan had been defeated. It had already been decided that Germany would be divided into zones overseen by Russia, Great Britain, and the United States. But at Yalta, Stalin agreed to allow France to rule a zone—as along as it came from English or U.S. territory.

Foremost on Stalin’s agenda was Poland. He wanted the country in the Soviet Union, claiming that it had traditionally been “the corridor through which the enemy passed into Russia.” Roosevelt agreed to this, although it constituted selling out Poland to Russia. This was much to Churchill’s dismay, because Great Britain had already recognized that Poland should become a free state after the war. But Roosevelt wanted something in return—Stalin’s promise to attack Japan, with which it had a nonaggression pact, within ninety days after Germany’s defeat.

Roosevelt has been heavily criticized for this decision, but at the time he did not know whether the atomic bomb would be developed in time to use against Japan, and he knew that any invasion of the Japanese home islands would be a bloodbath. He hoped that the creation of the United Nations—which Stalin agreed to join at Yalta—would help ameliorate Poland’s plight. Roosevelt would die of a cerebral hemorrhage in just over two months after Yalta. At the war’s end, Stalin did attack Japan, but mainly as a power grab in Manchuria. And Poland was unfortunately sucked back behind what Churchill would later name the “Iron Curtain.”

The Land War: Panzer Attack—The Mechanized Cavalry That Changed the Land War

While tanks and armored vehicles were just being introduced in the First World War, they were to become a decisive factor in the Second World War. In between the wars, military planners at first thought that tanks should merely be used as support tools for infantry.

However, numerous forward-thinking war planners—including Englishmen J.F.C. Fuller and Basil H. Liddell Hart and German general Heinz Guderian—believed in the use of all-mechanized armored divisions. The Germans in particular pioneered the idea of panzer (armored) divisions, creating the first ones in the mid-1930s. Infantry accompanied these divisions, in armored half-tracks, and there was mobile artillery as well, but the real killing force was two regiments of tanks that could be used to punch holes through enemy lines in advance of regular infantry. The Germans put this to good effect in Poland and France and during the initial stages of their rapid advance into Russia.

THE TIGER I, DEVELOPED BY THE GERMANS, SEEMED THE ULTIMATE OFFENSIVE MACHINE, BUT IT TOOK SO LONG TO PRODUCE THAT AMERICAN SHERMANS AND RUSSIAN T-34S QUICKLY OUTNUMBERED IT.

Prints & Photographs Division, Library of Congress, LC-USZC4-4415

The primary German tank of the war was the Tiger I, which was put into battle in early 1941. It was heavily armored, so much so that it had a problem crossing most bridges. It carried (along with two machine guns) the powerful German 88 gun, along with an extremely effective Zeiss optical aiming sight, so that the Tiger could knock out enemy tanks at a range of 1,600 yards (1.5 km).

This spelled trouble for U.S. Shermans and Russian T-34s, which had to close to 500 yards (457 m) or so before they could hope to penetrate the Tiger’s armor. But a major drawback of the Tiger was how long it took to produce. In the same amount of time that German factories could turn out 1,300 Tigers, 40,000 Shermans and 60,000 T-34s could be built. Ultimately, even with its overwhelming firepower, this doomed the Tiger.

Just as the tank was the symbol of land warfare in World War II, the aircraft carrier represented the sea. After World War I, many naval commanders continued to pin their strategic dreams on the huge dreadnought-class battleships, and these certainly played a crucial part in the naval war.

But aircraft carriers were pivotal. At the end of World War I, certain ships in the U.S. and British navies had been converted so that biplanes might take off from their decks, but the first purpose-built aircraft carrier was the HMS Hermes, built in 1918. This and other carriers built by the British, Japanese, and Americans in the interwar years carried ever larger planes whose function changed from mere scouting ahead of a task force of ships to bombing and torpedoing enemy vessels.

The first real blow from aircraft carriers came when British carrier ships destroyed half the Italian fleet at anchor at Taranto, Italy. The Japanese planes that devastated Pearl Harbor came from aircraft carriers. In return, aviator Billy Mitchell shocked the Japanese by bombing Tokyo only a few months after Pearl Harbor with sixteen B-25s secretly launched from a U.S. aircraft carrier.

In the most famous naval battle of the war, the Battle of Midway, fought mainly with naval aircraft, the Americans destroyed four carriers belonging to the Japanese and changed the course of the war in the Pacific.

World War II’s most destructive power, bar none, came from the sky, with the advent of the heavy bomber and its ability to drop tons of high explosive and incendiary bombs on both military and civilian targets. While the iconic image of World War I is long trenches snaking off through a barren wasteland, the one that most fully symbolizes World War II are the haunting ruins of a city, piles of rubble with a few scattered walls standing upright.

The British used the Wellington or the Lancaster; the Americans flew the B-25, B-17 Fortress, or B-29 Super Fortress; and the Germans employed the Junkel 88 or the Heinkel III, or even a jet bomber developed in late 1944, which was almost impossible to intercept because of its speed but came too late to affect the course of the war. The Japanese bomber was the fast but thinly armored Betty.

All of these airplanes were used against military targets, and all were used against civilian ones, as well. Deliberate terror bombing of civilian targets in an attempt to break enemy morale was a chief weapon of World War II, used most extensively after 1943 by the allies. In total, the United States and Great Britain dropped 2 million tons (1.8 billion kg) of bombs on Europe, killing 600,000 German civilians, 60 percent of them women and children. (About 60,000 British civilians died from German bombing.)

In the war in the Pacific, Americans wreaked havoc on the Japanese civilian population. In the low-level night bombing perfected by U.S. General Curtis LeMay, U.S. Superfortresses dropped incendiary bombs of jellied gasoline on the enemy, burning the wooden cities to the ground and creating huge firestorms. (Japan no longer had the air defenses to fight off the bombers, thus it could fly closer to its targets.) Two hundred thousand Japanese were killed, and another 13 million were made homeless. However, until the atomic bomb was dropped on Hiroshima, killing 80,000 people within a few hours, Japan refused to surrender.

In general, since the war’s end, it has been recognized that strategic bombing of military targets is highly effective in helping defeat an enemy. However, bombing population centers, far from bringing about a loss of morale, actually stiffens one’s opponents’ resistance.

IN A STILL-CONTROVERSIAL DECISION, PRESIDENT HARRY TRUMAN DROPPED THE ATOMIC BOMB ON JAPAN; THE MUSHROOM CLOUD OVER NAGASAKI IS SEEN HERE. IT TOOK THE TWO ATOMIC BOMBS AND THEIR COMBINED KILLING OF 200,000 BEFORE THE JAPANESE SURRENDERED.

Prints & Photographs Division, Library of Congress, LC-USZ62-39852

In August 1939, Albert Einstein wrote several letters to President Franklin Delano Roosevelt, informing him that nuclear fission—fragmenting a uranium atom’s nucleus by bombarding it with neutrons—might result in “an extremely powerful bomb of a new type.” Einstein also told Roosevelt something even more alarming: The Germans had forbidden the export of uranium and were already working on this experimental weapon. He urged Roosevelt to help set up a program to develop an atomic bomb ahead of the Germans.

At Roosevelt’s request, scientists who had already been working on nuclear fission—including Enrico Fermi, Edward Teller, and J. Robert Oppenheimer—came together with numerous others in the early 1940s. Fermi, at the University of Chicago, built the first successful nuclear reactor, which showed that controlled nuclear fission could work. This was a huge step in the development of the atomic bomb, whose complex mystery was solved step by step by the top secret Manhattan Project, headed by Oppenheimer, with locations in New York and all over the country, including the Los Alamos Laboratories in New Mexico.

On July 16, 1945, the first atomic bomb, its core the more stable and powerful plutonium rather than uranium, was exploded atop a tower near Alamogordo, New Mexico. Fermi wrote that the explosion resulted in “a huge pillar of smoke with an expanded head like a gigantic mushroom.” The blast, more powerful than even the scientists thought, brought on temperatures so hot (7,000°F [3,871°C]) that the nearby sand was fused together.

President Roosevelt had died earlier that year, but President Harry S. Truman made the decision to drop the atom bomb on Japan only a month after this first test. It was a decision that ended World War II, and helped begin the Cold War.

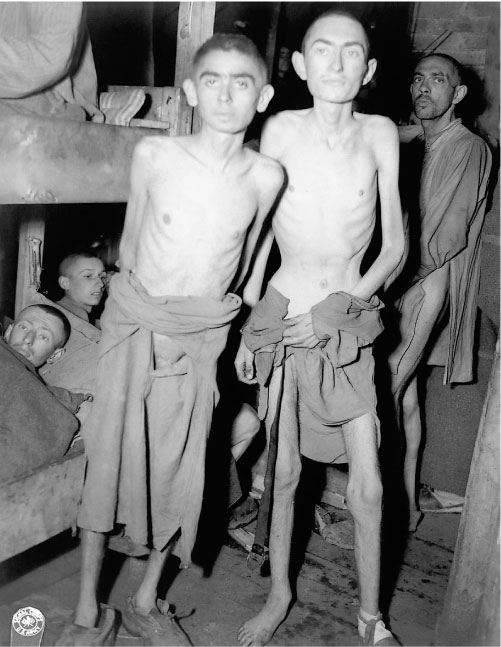

As historian John Keegan has pointed out, one of the things that makes Hitler’s killing of more than 6 million Jews (as well as other “undesirables,” such as Gypsies, the mentally challenged, Polish and French resistance fighters, and clergy) even more shocking is that, while hundreds of thousands, even millions, were killed in campaigns by the likes of the Romans, Mongols, and Spanish, “massacre had effectively been outlawed from warfare in Europe since the seventeenth century.” With Hitler, massacre on an unimaginable scale was back.

After the Nazis took power in the 1930s, Jews in Germany suffered under a series of restrictive legal measures that culminated in the Nuremberg Laws of 1935, in which Jews were deprived of German citizenship. There were about a half a million Jews in Germany at the time and while a fifth of this population attempted to migrate, many of them went to nearby countries that were soon subsumed in the Nazi onslaught. Heinrich Himmler, head of the German SS, devised four task groups divided into Sonderkommandos, or Special Commandos, which killed roughly 1,000,000 Jews in the newly conquered areas of Poland and Russia. But these deaths were mainly by shooting, which Himmler considered unproductive and slow.

In 1942, he proposed what he called the Endlosung, or Final Solution, at the behest of Hitler. The Endlosung took Jews from the ghettos in major cities to where they had been confined and brought them to concentration camps. Some of these were work camps, where inmates were literally worked to death. Others, like Treblinka and Sobidor, were simply extermination camps where Jews were herded into gas chambers as soon as they arrived.

SEEN HERE ARE TWO INMATES OF THE AMPHING CONCENTRATION CAMP IN GERMANY JUST AFTER BEING LIBERATED BY U.S. TROOPS.

Prints & Photographs Division, Library of Congress, LC-USZ62-128310

By the spring of 1944, there were twenty concentration camps and some 160 smaller labor camps, and some 6 million Jews—40 percent of the world’s Jewish population—had been killed. The fact that a supposedly civilized people in the middle of the twentieth century could massacre so many is one the world has struggled with ever since. However, the wave of sympathy for the plight of the Jews immediately after World War II was in part what helped them gain their own homeland and statehood.