Ballad on Seeing a Pupil of the Lady Kung-Sun Dance The Sword Mime

On the 19th day of the Tenth Month of Year II of Ta-li (15 November 767), I saw the Lady Li, Twelfth, of Lin-ying dance the Mime of the Sword at the Residence of Lieutenant-Governor Yüan Ch’i of K’uei Chou Prefecture; and both the subtlety of her interpretation and her virtuosity on points so impressed me that I asked of her, who had been her Teacher? She replied: ‘I was a Pupil of the great Lady Kung-sun!’

In Year V of K’ai-yüan (A.D. 717), when I was no more than a tiny boy, I remember being taken in Yü-yen City to see Kung-sun dance both this Mime and ‘The Astrakhan Hat’.

For her combination of flowing rhythms with vigorous attack, Kung-sun had stood alone even in an outstanding epoch. No member at all of the corps de ballet, of any rank whatever, either of the Sweet Springtime Garden or of the Pear Garden Schools, could interpret such dances as she could; throughout the reign of His Late Majesty, Saintly in Peace and Godlike in War! But where now is that jadelike face, where are those brocade costumes? And I whiteheaded! And her Pupil here, too, no longer young!

Having learned of this Lady’s background, I came to realize that she had, in fact, been reproducing faithfully all the movements, all the little gestures, of her Teacher; and I was so stirred by that memory, that I decided to make a Ballad of the Mime of the Sword.

There was a time when the great calligrapher, Chang Hsü of Wu, famous for his wild running hand, had several opportunities of watching the Lady Kung-sun dance this Sword Mime (as it is danced in Turkestan); and he discovered, to his immense delight, that doing so had resulted in marked improvement in his own calligraphic art! From that, know the Lady Kung-sun!

A Great Dancer there was,

the Lady Kung-sun,

And her ‘Mime of the Sword’

made the World marvel!

Those, many as the hills,

who had watched breathless

Thought sky and earth themselves

moved to her rhythms:

As she flashed, the Nine Suns

fell to the Archer;

She flew, was a Sky God

on saddled dragon;

She came on, the pent storm

before it thunders;

And she ceased, the cold light

off frozen rivers!

Her red lips and pearl sleeves

are long since resting,

But a dancer revives

of late their fragrance:

The Lady of Lin-ying

in White King city

Did the piece with such grace

and lively spirit

That I asked! Her reply

gave the good reason

And we thought of those times

with deepening sadness:

There had waited at Court

eight thousand Ladies

(With Kung-sun, from the first,

chief at the Sword Dance);

And fifty years had passed

(a palm turned downward)

While the winds, bringing dust,

darkened the Palace

And they scattered like mist

those in Pear Garden,

On whose visages still

its sun shines bleakly!

But now trees had clasped hands

at Golden Granary

And grass played its sad tunes

on Ch’ü-t’ang’s Ramparts,

For the swift pipes had ceased

playing to tortoiseshell;

The moon rose in the East,

joy brought great sorrow:

An old man knows no more

where he is going;

On these wild hills, footsore,

he will not hurry!

Tu Fu celebrates the work of a fine though ageing ballerina, seen at White King city in the Yangtse Gorges when he was on one of his river tours, by means of the heroic ballad form which he had used to celebrate the work of the old painter in the poems on pp. 209 and 213.

He gives the date of her performance in his prose introduction to the ballad; but the date of ‘717’ for his being taken to see the great Lady Kung-sun herself results from an emendation of the usual text: this has ‘715’, which would be K’ai-yüan III, a 3 and a 5 being easily confused in rapid Chinese handwriting. The emendation makes the little Tu Fu five instead of three years old, which is much more probable; and would be exactly fifty years earlier, as he says in the ballad.

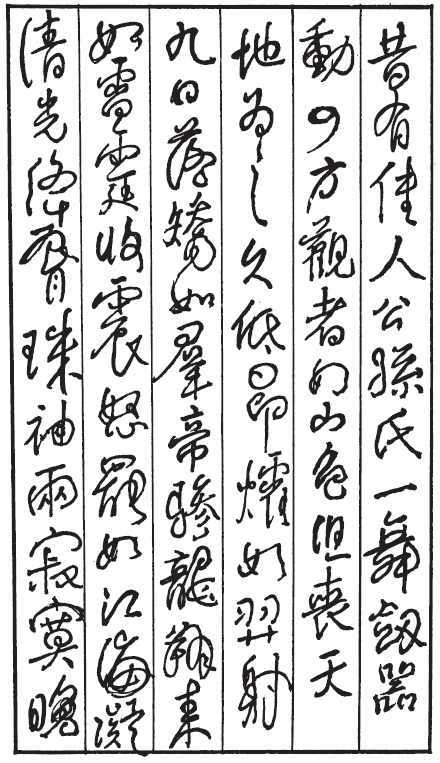

For drama, the beginning in China was the Yüan (Mongol) dynasty, 1280-1368; * it does not seem to have existed as such in the T’ang dynasty when the arts of the theatre were ballet, song and mime. From descriptions of this dance which Tu Fu saw, it was a solo danced without any ‘props’ (thus there was no sword in the ballerina’s bare hands, but she mimed it); while she is said to have worn a martial, male costume. Tu Fu is therefore thinking of Kung-sun herself and how she usually looked, as a ballerina rather than in this particular piece, when he remembers her ‘red lips and pearl sleeves’. Tu Fu says the piece was danced in the style of ‘West of the Yangtse’ (translated as ‘Turkestan’), and it was probably at its climax extremely fast and vigorous, much like Tartar or so-called Polovtsian dances known today through Russian ballet. ‘The Astrakhan Hat’ is likely to have been similar. None of the calligraphy of the ‘mad monk’ Chang Hsü of Wu, though among the most famous of its day, survives; but there is calligraphy by a contemporary, probably Huai-su, in much the same style, of ‘grass’ or ‘rough draft’ shorthand – a style in which Chairman Mao excels today. Huai-su’s wild calligraphy seems to give an impression of what the Lady Kung-sun’s dancing must have been like.* (The Chinese art of calligraphy in all its styles is closely related to the art of ballet; as indeed is the Chinese art of poetry.)

The Sweet Springtime Garden was the name of the park with the Serpentine, in ‘Lament by the Riverside’: it seems there was a ballet school there with a particular style. The Pear Garden survives today as a name for a theatre, or for ‘the theatre’ as an art and profession: it was established by the Glorious Monarch himself, in a pear orchard inside the Forbidden Garden of the Imperial Palace, as a school of music and dancing with 300 students. (Tu Fu’s ‘eight thousand ladies’ in the ballad elicits from an old Chinese commentator: ‘What a glorious exaggeration!’) In this part of the prose preface Tu Fu goes into some technicalities of the organization of the corps de ballet, rather like a journalist and apparently getting it all rather wrong: these technicalities have been omitted. David Hawkes suggests, with great probability, that there was a sad irony now in Tu Fu’s reference to the Glorious Monarch as ‘Saintly in Peace and Godlike in War’.

In the ballad itself, ‘the Nine Suns fell to the Archer’ long ago, when there rose ten suns in the heavens and they scorched all the earth until a god called the Great Archer took his bow and shot nine of them down.

Although it is difficult to be sure, without personal pronouns, I think that Tu Fu’s conversation with the ballerina, the Lady of Lin-ying, was not confined to question and answer, but continued (so, ‘we thought of those times’); that the lines in parenthesis are her contributions, she making the ballet gesture of a palm turned downward for the passage of time when he says that fifty years have passed; and that he is looking at her face at the end of their conversation.

Golden Granary, where the Glorious Monarch was buried outside Ch’ang-an (he had died in 762), has already been mentioned at the end of the poem on p. 210 and in its note. Ch’ü-t’ang is the Yangtse gorge, near White King, in the fifth verse of Li Po’s ‘Ballad of Ch’ang-kan’ (p. 125). The ‘Ramparts’ might refer to the sides of the gorge, or be the walled city of White King itself referred to thus in a kenning; but as usual in such cases in Chinese poetry, it can probably be said to be a bit of both. Ch’ang-an and White King (K’uei-chou) are far apart, so that this verse is like saying: ‘Now trees have clasped hands at Windsor Great Park, and grass plays its sad tunes on Edin’s Ramparts’; indicating the melancholy that Tu Fu imagines as falling over the whole of China. But he imagines this on the ceasing of the music of ‘the swift pipes’ he has been listening to while watching the dancing, now, and not as part of what went before the asterisk I have inserted. These sudden shifts of space and time are common in Chinese poetry; and sometimes disconcerting to us, accustomed as we are to logical nexus.

‘Playing to tortoiseshell’ is abbreviated in the translation (‘tortoiseshell’ being a long word, but essential to retain) from ‘playing to tortoiseshell-bordered mats’. The Chinese in T’ang times sat on mats on the floor at banquets, where such ballets were staged, like the Japanese of today; who retain much of earlier Chinese customs and dress. Tortoiseshell-bordered mats were very grand.

These lines win from the old Chinese commentator already quoted: ‘Surely a god was guiding his brush when he wrote this!’ The magic, I think, is partly in the ‘visual rhyme’ of ‘tortoiseshell’ with ‘the moon rose in the East’: much as one might speak of the ‘visual rhyme’ in ‘I’ll hang my harp on a weeping willow tree’. ‘Joy brings the greatest sorrow’ is a proverb. This might have some kind of allusion to Yang Kuei-fei, at one level, but seems chiefly to evoke, together with the last verse, a well-known ‘after theatre’ feeling everyone has experienced after witnessing something especially moving. One has been to the ballet with Tu Fu in the eighth century.