l

Landowska, Wanda (1879-1959)

Wanda Landowska, a member of Natalie Clifford Barney's famed lesbian salon, was almost singlehandedly responsible for the revival of the harpsichord as a performance instrument in the twentieth century. In her enthusiastic research to uncover the forgotten music and performance styles of the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries, she paved the way for today's interest in authentic performances of early music on original instruments.

Landowska, born on July 5, 1879, in Warsaw, Poland, was a musical prodigy who began playing the piano at the age of four and from a very young age was trained at the Warsaw Conservatory. At fifteen, she went to Berlin to study composition and, though she was a rather rebellious student, began to win prizes in major competitions for her songs and piano works.

While in Berlin, she met the Polish folklorist Henry Lew, who encouraged her research and performance of early music, and assisted her in writing her book, Musique ancienne (1909). In 1900, she married Lew and moved with him to Paris, where she was able to gain a greater audience.

While the relationship was a mostly supportive one, Landowska wished to be relieved of the sexual aspects of marriage. Accordingly, she arranged a ménage à trois by hiring a maid who would also function as Lew's mistress. The situation was apparently satisfactory for all involved, and, even after Lew died in 1919, the maid remained in the musician's service until the latter's death.

Landowska's fame grew quickly, and in 1903 she gave her first public performance on the harpsichord, an instrument that, by the nineteenth century, was considered "feeble" in its dynamics and rendered obsolete by the piano. Landowska ferociously championed its use through her performances and writing; she commissioned the construction of new harpsichords; and, in 1913, she returned to Berlin to establish a class devoted to the instrument at the Hochschule für Musik.

In 1920, Landowska settled in Paris, where she became a frequent guest in Barney's circle, often providing musical accompaniment for the various artistic functions of the renowned lesbian salon.

While she toured extensively and recorded during the 1920s, she also began another phase of her career by establishing the École de Musique Ancienne near Paris, which attracted students from many nations. She was recognized as one of the great music teachers of her time, and was rumored to have engaged in a rivalry with Nadia Boulanger, the other great female musical pedagogue, for the romantic affections of a number of young women in their tutelage.

In the 1930s, Landowska met Denise Restout, who became, in turn, her student, her life companion, and the preserver of her artistic legacy.

Landowska's fame and success continued to grow through the 1930s, but, with the Nazi invasion of France in 1940, she lost her school, her property, her extensive library, and all her instruments. She and Restout escaped to southern France and then to Lisbon, and finally arrived in New York as refugees.

Although Landowska had virtually nothing left to her but her talent, she nonetheless reestablished herself in the United States as a performer and teacher. Through the 1940s, she toured extensively and made her landmark recording of Johann Sebastian Bach's Goldbergvariations, a work she restored to performance on the instrument for which it had been composed.

She continued to work tirelessly until her death on August 16, 1959, at her home in Lakeville, Connecticut. After her death, Restout devotedly edited and translated her writing on music.

Landowska was decorated by the governments of Poland and France, and she was widely respected by her fellow musicians. She thoroughly transformed the performance and reception of early music in the modern period, and, through her pioneering efforts, the harpsichord is frequently heard in many diverse musical genres today.

—Patricia Juliana Smith

BIBLIOGRAPHY

Benstock, Shari. Women of the Left Bank: Paris, 1900-1940. Austin: University of Texas Press, 1986.

Landowska, Wanda. Landowska on Music. Denise Restout, ed. and trans. New York: Stein and Day, 1964.

Sachs, Harvey. Virtuoso: The Life and Art of Niccolò Paganini, Franz Liszt, Anton Rubinstein, Ignace Jan Paderewski, Fritz Kreisler, Pablo Casals, Wanda Landowska, Vladimir Horowitz, Glenn Gould. New York: Thames and Hudson, 1982.

SEE ALSO

Classical Music; Boulanger, Nadia

Lane, Nathan (b. 1956)

AHIGHLY ACCLAIMED ACTOR, NATHAN LANE HAS appeared on stage, screen, and television. He has starred in Broadway productions of Guys and Dolls, A Funny Thing Happened on the Way to the Forum, Love! Valour! Compassion!, and The Producers. He has received numerous acting honors, including two Tony Awards. Openly gay himself, he has portrayed gay characters in several plays and also on screen in Frankie and Johnny and The Birdcage.

One of the most accomplished comic actors of his generation, Lane has an appealing presence that has earned him the admiration of legions of fans and critics. Although his métier is that of comedy, he is remarkably versatile. As Alex Witchel has observed, "Lane is an outsize talent who can belt it to the balcony and back, cajoling and beguiling with song, laughs, a few lumps in the throat. With his classic clown's face, part bulldog, part choirboy, he can be good and evil, smart and stupid, funny and sad, sometimes all in one number."

The youngest of three sons of Daniel Lane, a truck driver, and Nora Lane, a secretary, he was born Joseph Lane on February 3, 1956, in Jersey City, New Jersey. Around the time of his birth, his father's eyesight began to fail. Unemployed, the father fell victim to alcoholism and eleven years later "drank himself to death," according to his son.

When Lane was in his early teens, his mother began to suffer from manic depression severe enough to require occasional hospitalization. Lane's older brother Daniel became a surrogate father to him and encouraged his love of reading and theater.

Lane began acting while attending St. Peter's Preparatory School in Jersey City. He won a drama scholarship to St. Joseph's College in Philadelphia, but even with the award, the family could not afford the expense of college, and so he began working as an actor.

As Lane established himself in the profession by performing in dinner theater and children's productions, he supplemented his income with various jobs, including telemarketing, conducting surveys for the Harris poll, and delivering singing telegrams.

At the age of twenty-two, Lane registered with Actors' Equity. Since there was already a performer listed as Joe Lane, he changed his first name from Joseph to Nathan after the character Nathan Detroit in Guys and Dolls, whom he had played in dinner theater the previous year.

With Patrick Stark, Lane formed a comedy team called Stark and Lane. The duo, based in Los Angeles, worked at clubs, opened concerts, and made occasional television appearances. After a couple of years, Lane quit the act, which was not particularly profitable because of the travel expenses involved. In addition, Lane wanted to return to New York.

Before leaving California, Lane auditioned for and won a part in One of the Boys, a situation comedy starring Mickey Rooney. The series, which was filmed in New York, ran for only thirteen episodes in 1982, but it brought Lane to the attention of the public.

In the same year, Lane made his Broadway debut, playing Roland Maule in Noël Coward's Present Laughter, directed by George C. Scott. His performance met with critical approval, and he went on to appear in a number of plays, including Goldsmith's She Stoops to Conquer (1984, directed by Daniel Gerroll), Shakespeare's Measure for Measure (1985, directed by Joseph Papp), Simon Gray's The Common Pursuit(1986-1987, directed by Simon Gray and Michael McGuire), and August Darnell and Eric Overmyer's A Pig's Valise (1989, directed by Graciela Daniele), as well as two unsuccessful musicals, Elmer Bernstein and Don Black's Merlin (1982-1983, directed by Frank Dunlop) and William Perry's Wind in the Willows(1985-1986, staged by Tony Stevens).

In 1987, Lane made his film debut playing a ghost in Hector Babenco's Ironweed, based on the novel by William Kennedy.

In 1989, Lane played his first gay role as Mendy in Terrence McNally's The Lisbon Traviata, directed by John Tillinger. His performance earned him the Drama Desk Award for best actor in a play.

Lane's association with McNally has been long and successful. In 1990, he acted in McNally's Bad Habits(directed by Paul Benedict), and in 1991, he appeared in the playwright's Lips Together, Teeth Apart (directed by Tillinger). In the latter he played a homophobic character.

In the early 1990s, Lane had roles in half a dozen films, including Frankie and Johnny (1991, directed by Garry Marshall), which was based on a play by McNally. In it he played the gay friend of Frankie, the female lead.

In 1992, Lane returned to Broadway in a revival of Frank Loesser's Guys and Dolls, directed by Jerry Zaks. His performance as Nathan Detroit earned him rave reviews and another Drama Desk Award, this one for best actor in a musical, as well as a Tony nomination. The next year, he was well-received as the star of Neil Simon's Laughter on the 23d Floor, also directed by Zaks.

In 1994, Lane supplied the voice of Timon the meerkat in Rob Minkoff's The Lion King. Lane teamed with Ernie Sabella, who voiced Pumbaa the warthog, on the movie's extremely popular song "Hakuna Matata." Lane has since been the voice of other animated characters, including a cat in the film Stuart Little (1999, directed by Minkoff) and a dog in the Disney cartoon show Teacher's Pet, for which he won a Daytime Emmy Award.

In 1994, Lane worked in another play by McNally, Love! Valour! Compassion! (directed by Joe Mantello).

He earned a Drama Desk Award as best featured actor in a play for his complex and moving portrayal of a gay man with AIDS.

Lane next appeared in a 1996 revival of Stephen Sondheim's A Funny Thing Happened on the Way to the Forum, directed by Zaks. Starring as Pseudolus, a Roman slave, Lane garnered enthusiastic reviews and a Tony Award for best performance by a leading actor in a musical.

In 1996, Lane played drag queen Albert opposite Robin Williams's Armand in Mike Nichols's film The Birdcage, a remake of Edouard Molinaro's 1978 film based on Jean Poiret's play, La Cage aux Folles. The film, with a script by Elaine May and Mike Nichols, was set in Miami's South Beach. Although controversial in a number of quarters, especially for its stereotypical portrait of a gay couple, the film was a commercial success, and Lane's performance was described as "wide-ranging [and] inventive."

Lane starred in a CBS situation comedy entitled Encore! Encore! in 1998-1999. He played a retired opera singer who returns to his home in the Napa Valley to assume management of his family's winery. Lane's original concept for his character was that of a "diva chef in a five-star restaurant" who had come out and was raising his son.

As it turned out, however, his character was entirely heterosexualized and he played an (unlikely) womanizer. Despite his own good acting (and the presence of veteran actress Joan Plowright, who played his mother), the show failed to attract an audience and was soon canceled.

Lane's recent work includes a 2000 production of Moss Hart and George S. Kaufman's The Man Who Came to Dinner (directed by Zaks) and, most successfully, a starring role in Mel Brooks's The Producers(2001, directed by Susan Stroman), described as "the biggest hit on Broadway in more than a decade." Lane won a Tony Award for best actor in a musical for his hilarious performance as Max Bialystock.

In 2002, Lane appeared as Mr. Crummles in Douglas McGrath's film version of Dickens's Nicholas Nickleby.The actor, who has a "talent holding deal" with CBS, also was chosen to star in a comedy series in which he will play a gay congressman. The show has not yet been scheduled.

In 2004, Lane opened to mixed reviews in a musical adaptation of Aristophanes' The Frogs, with a book by Bert Shrevelove and music and lyrics by Stephen Sondheim. The show was originally produced in 1974 at the Yale School of Drama; for the 2004 production Lane freely adapted Shrevelove's book and starred as Dionysos, the god of theater.

Lane has never made a secret of his homosexuality. He came out to his family when he was twenty-one and about to move in with a lover. He did not comment publicly on his sexual orientation until 1999, however.

Lane has been criticized by some activists in the gay community for waiting so long to come out publicly. In an interview in the Advocate he explained that he "[found] it difficult to discuss [his] personal life with total strangers" but was moved to speak out after the murder of gay college student Matthew Shepard. "At this point it's selfish not to do whatever you can," said Lane. "If I...say I'm a gay person, it might make it easier for somebody else. So it seems stupid not to."

In other interviews Lane has alluded to an "on-again-off-again relationship with an actor who lives in Los Angeles," but has otherwise maintained privacy about his personal relationships.

—Linda Rapp

BIBLIOGRAPHY

"Lane, Nathan." Current Biography Yearbook 1996. Judith Graham, ed. New York: The H. W. Wilson Company, 1996. 286-289.

"Lane, Nathan." Contemporary Theatre, Film and Television. Michael J. Tyrkus, ed. Detroit: Gale Group, 2000. 201-203.

Vilanch, Bruce. "Citizen Lane." Advocate, February 2, 1999, 30.

Witchel, Alex. " 'This Is It—As Happy as I Get, Baby.' Nathan Lane." New York Times, September 2, 2001.

SEE ALSO

Musical Theater and Film; Coward, Sir Noël; Sondheim, Stephen

lang, k.d. (b. 1961)

LONG BEFORE SHE CAME OUT AS A LESBIAN IN A 1992 interview in the Advocate, and long before she appeared on the 1993 cover of Vanity Fair lounging in male drag in a barber's chair with Cindy Crawford hovering teasingly over her, lesbians had made k.d. lang their own. They were drawn not only by her genderbending hairstyle and clothes, but also by her achingly beautiful voice and her intensely romantic singing style.

A country girl, lang, whose given name is Kathryn Dawn, grew up in the tiny Canadian town of Consort, deep in Alberta's farming territory. She came out as a lesbian while still a teenager and moved to Edmonton, where she joined a performance art group called GOYA, Group of Young Artists.

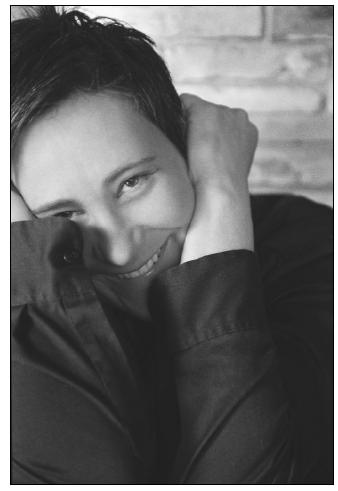

k.d. lang, photographed by Jeri Heiden.

When she began to sing country music, it was part tribute to her country roots, part performance art, and part camp. But lang's rich voice and deeply felt interpretations gave her legitimacy as a country artist. She released three country albums, A Truly Western Experience (1984), Angel with a Lariat (1987), and Absolute Torch and Twang (1989). She won Grammy Awards for Absolute Torch and Twang and for her version of the Roy Orbison classic "Crying."

Although the country music establishment rewarded lang in spite of her eccentricities of dress and identity, the more conservative country audiences had a harder time accepting her, especially after she went public as a vegetarian and made an antimeat television commercial.

The message,"Meat Stinks!, "roused anger in the farming communities that love country music. Among the communities responding negatively to the commercial was Consort: In retaliation, her hometown removed the plaque that had identified it as the "Home of k.d. lang."

Lesbians, who had been sure for years that lang was one of them, were pleased when she became one of very few major celebrities to come out openly as gay. However, since lang stood virtually alone on the mainstream stage, her lesbian fans often expected her to represent every aspect of what they considered important about being queer.

lang, who does not view her lesbianism as the central factor of her life, found it difficult and often painful when she was criticized for not living up to the diverse demands of her audience.

However, she does stand up as a lesbian when she feels it is important. She has spoken and performed at gay demonstrations and AIDS benefits. In 1997, she joined another famous lesbian making the transition out of the closet when she guest-starred with Ellen DeGeneres on two episodes of Ellen.

Along with her emergence as an out lesbian, lang began to expand and experiment with her musical style. In 1992, the same year that she came out, she released Ingenue, a collection of her own compositions in the style of the "torch" ballads of the 1940s. This departure from country would be her most commercially successful album, going double platinum and winning a Grammy for its signature song, "Constant Craving."

lang followed this success with another original album in 1995, All You Can Eat; and in 1997, she released Drag, a compilation of old songs unified by the common theme of smoking cigarettes.

Between 1997 and 2000, she took a break from recording and performing to relax and gather her forces after her breakneck rise to fame. During this time, she moved from a farm near Vancouver, British Columbia, to a glass-and-wood "cabin" in the woods near Los Angeles. Also during this time, she fell in love with Leisha Hailey of the girl group The Murmurs.

lang's sabbatical and her increasingly solid relationship with Hailey resulted in a newly successful return to music. In the summer of 2000, she released Invincible Summer, an album of original love songs with a breezy summery tone, reflecting the influence of Brazilian music and the Beach Boys. The album and its accompanying tour received rave reviews.

lang's most recent albums are Live by Request(2002), recorded from the A&E television series of the same name; and, with Tony Bennett, Wonderful World

(2003), in which the duo sing songs inspired by Louis Armstrong. For the latter work, Bennett and lang received a Grammy Award in the category Best Traditional Pop Album. In Hymns of the 49th Parallel(2004), lang performs Canadian songs.

k.d. lang remains an anomalous figure in the music world, both because she is a lesbian and because she refuses to confine herself to a specific genre. Always an experimenter, she resists neat categorization. But her sincerity, charm, and compelling voice continue to attract a wide variety of listeners.

—Tina Gianoulis

BIBLIOGRAPHY

Appelo, Tim. "Is k.d. lang Really Patsy Cline?" Savvy, July 1988, 18.

Bennetts, Leslie. "k.d. lang Cuts It Close." Vanity Fair, August 1993, 94.

Kort, Michele. "k.d.: A Woman in Love." Advocate, June 20, 2000, 50.

Robertson, William. k.d. lang : Carrying the Torch. Toronto, Ont. and East Haven, Conn.: ECW Press, 1993.

Sischy, Ingrid. "k.d." Interview, September 1997, 138.

Starr, Victoria. k.d. lang : All You Get Is Me. New York: St. Martin's Press, 1994.

Stein, Arlene. "Androgyny Goes Pop; But Is It Lesbian Music?" OutLookNo. 12 (Spring 1991): 26-31.

Udovich, Mim. "k.d. lang." Rolling Stone, August 5, 1993, 54.

SEE ALSO

Popular Music; Country Music; Music Video; Rock Music; Women's Music; Etheridge, Melissa

Laurents, Arthur (b. 1918)

PLAYWRIGHT, LIBRETTIST, SCREENWRITER, AND DIRECTOR, Arthur Laurents brought an independent sensibility to some of the most important works of stage and screen in the post-World War II era.

He dared to live openly with a male lover in Hollywood in a period when the studios insisted upon the appearance of sexual conformity. And, in prime examples of what theorist Wayne Koestenbaum has termed "male double writing," Laurents collaborated with such major gay talents as Stephen Sondheim, Leonard Bernstein, Jerry Herman, Harvey Fierstein, and Jerome Robbins on musicals that challenged audiences to accept an unorthodoxy that goes against the grain of the American success myth.

In Laurents's The Time of the Cuckoo (1952), the courtly Renato Di Rossi, asked by a judgmental American spinster to justify the dishonesty required for his extramarital affairs, replies simply, "I am in approval of living." So, apparently, is Laurents.

Laurents was born on July 14, 1918, in the Flatbush section of Brooklyn to middle-class Jewish parents from whom he inherited socialist leanings.

Following graduation from Cornell University, Laurents served during World War II in an army film production unit in Astoria, Queens, where he wrote scripts designed to educate servicemen going overseas, as well as radio plays intended to foster civilian support for the war.

The success of Laurents's first commercially produced play, Home of the Brave (1945)—written in nine days and critically applauded for addressing the issue of anti-Semitism in the armed forces—encouraged him to move to Hollywood, then in its heyday.

In the film industry, Laurents quickly became known for his deftness with psychological themes. He wrote the scripts for The Snake Pit (1948), the story of a woman's emotional collapse and recovery, set in a mental asylum, with scenes considered shockingly realistic at the time; and Alfred Hitchcock's Rope (1948), a psychological thriller with a powerful homosexual subtext, which starred Laurents's then lover, Farley Granger.

Although Laurents was never blacklisted himself, his opposition to the studio heads' support of the communist witch hunts weakened his status in Hollywood.

He returned to New York, where he enjoyed success as a playwright (Time of the Cuckoo, 1952; A Clearing in the Woods, 1957; Jolson Sings Again, 1999), librettist (West Side Story, 1957; Gypsy, 1959; Anyone Can Whistle, 1964; Do I Hear a Waltz?, 1965; Hallejulah, Baby!, 1967; Nick and Nora, 1992), and director (I Can Get It for You Wholesale, 1962; the 1973 London premiere and 1989 Broadway revival of Gypsy; La Cage aux Folles, 1983).

Although he returned to Hollywood to work on the films The Way We Were (1973) and The Turning Point (1977), he has lived contentedly with his lover, Tom Hatcher, on a beachfront property in Quogue, Long Island, for almost fifty years, since 1955.

Laurents's experience of discrimination as both a Jew and a gay man—intensified by his experience during the Hollywood blacklist period—infuses his work with a strong social conscience.

In The Way We Were, Katie Morosky is marginalized both by her Jewish ethnicity and by her unflagging pursuit of social justice; her tragedy is to fall in love with Hubbell Gardner, a WASP who assimilates social norms so effortlessly that, finally, he has no principles.

Laurents also treated the subject of blacklisting in Jolson Sings Again, which dramatizes the sacrifices of life and integrity made to the McCarthyite drive to root out possible subversives.

Laurents's musical Hallelujah, Baby!, written for his good friend Lena Horne, looks at sixty years of race relations in America and was advertised as a "civil rights musical."

While Laurents followed the basic plot of Shakespeare's Romeo and Juliet in his book for West Side Story, he made two significant changes in the story. Rather than chance, it is the racial prejudice of the Jets/Montagues that prevents Anita/the messenger from delivering to Tony/Romeo the assurance that Maria/Juliet is still alive; and Maria/Juliet lives to confront the survivors with the evidence of what their hatred has cost the community.

Laurents suggested the "Officer Krupke" scene in West Side Story, which comically analyzes society's inability to deal with the juvenile delinquents who have been created by the mainstream's own misguided values.

Laurents's willingness to challenge social conventions makes him particularly interested in the relative values of madness and sanity. The relativity of normalcy is clear in Time of the Cuckoo, where Laurents satirizes American tourists in Venice who are unimaginative, insensitive, and self-centered, yet certain of their own superiority to the supposedly childlike, sexually undisciplined, immoral—yet clearly happier—Italians.

More provocatively, one of the settings for Anyone Can Whistle is a sanitarium called The Cookie Jar, described as catering to "the socially pressured"; the brilliant "Cookie Chase" scene underscores the contradictions in the American pursuit of success and happiness, which drives social authorities to attempt to destroy any instance of potentially subversive originality. Rose's breakdown in the climactic scene of Gypsydramatizes the consequence of striving for success at any cost.

Laurents is at his best when depicting a female character's search for liberation from the social strictures that demand conformity. In Gypsy, Rose angrily protests to her father that her own two daughters will "have a marvelous time! I'll be damned if I'm gonna let them sit away their lives like I did. And like you do—with only the calendar to tell you one day is different from the next!"

Laurents's most daring decision was to focus Gypsy not on the title character, on whose memoirs the play was based, but on Gypsy Rose Lee's mother, making the play the portrait of a woman so determined to break free of the humdrum that she is unaware of the moral monster she becomes in the process.

In The Turning Point, middle-aged friends Deedee Rogers and Emma Jacklin are forced to confront the choices made earlier in life that led one to leave the ballet stage to marry and raise a family in obscurity, and the other to become an internationally famous ballerina with an unsatisfying private life.

In A Clearing in the Woods, Virginia learns that "an end to dreams isn't an end to hope." And in Time of the Cuckoo, Leona Samish must let go of her unrealistic romantic expectations and accept the moment as life offers it. As Di Rossi advises Leona, "You are a hungry child to whom someone brings—ravioli. 'But I don't want ravioli, I want beefsteak!' You are hungry, Miss Samish! Eat the ravioli!"

Daring to aspire to a life beyond the humdrum, yet courageous enough to resist the corresponding temptation to be blinded by romantic illusion, Laurents's female characters are portraits of human resilience. They spoke strongly to the pre-Stonewall generation of gay men, themselves experimenting with constructing an alternative, more satisfying existence.

—Raymond-Jean Frontain

BIBLIOGRAPHY

Laurents, Arthur. Original Story by Arthur Laurents: A Memoir of Broadway and Hollywood. New York: Applause Theatre Books, 2000.

Mann, William J. Behind the Screen: How Gays and Lesbians Shaped Hollywood, 1910-1969. New York: Viking Penguin, 2001.

Miller, D. A. "Anal Rope." Inside/Out: Lesbian Theories, Gay Theories. Diana Fuss, ed. New York: Routledge, 1991. 119-141.

Mordden, Ethan. Coming up Roses: The Broadway Musical in the 1950s. New York: Oxford University Press, 1998.

____. Open a New Window: The Broadway Musical in the 1960s. New York: Palgrave, 2001.

SEE ALSO

Musical Theater and Film; Bernstein, Leonard; Herman, Jerry; Robbins, Jerome; Sondheim, Stephen

Liberace (1919-1987)

MR. SHOWMANSHIP, THE CANDELABRA KID, GURU OF Glitter, Mr. Smiles, The King of Diamonds, and Mr. Box Office, Wladzui "Walter" Valentino Liberace was for many the epitome of camp, excess, and flamboyance, yet he was also a gay man who steadfastly refused to acknowledge publicly his sexual identity.

Born into a musical family on May 16, 1919, in West Allis, Wisconsin, Liberace learned to play the piano by ear at the age of four. As a teenager, he played popular tunes in local Milwaukee movie theaters and nightclubs as Walter Buster Keys. He also continued his classical training, debuting as a soloist with the Chicago Symphony in 1940.

After a brief stint with the Works Progress Administration Symphony Orchestra, Liberace attended the Wisconsin College of Music on scholarship.

An encore request after a 1939 classical recital altered Liberace's career path. His performance of the popular tune "Three Little Fishes" in a semiclassical style proved an immediate audience favorite.

Soon armed with his trademark candelabra on the piano, Liberace found himself booked into dinner clubs and hotels from coast to coast. Audiences immediately responded to his unique musicianship, which blended classical and popular music with glamour and glitter.

In 1950, Walter Valentino Liberace officially changed his name to Liberace. With an act that now included witty banter and some singing, the performer positioned himself to tackle a new market: television.

Begun in 1952 as a summertime replacement for The Dinah Shore Show, within two years The Liberace Showwas the most watched program in the country. The show was on the air until 1956 and garnered Liberace a huge fan base. By 1954 he was earning over $1 million a year with sixty-seven albums on the market, outselling even pop sensation Eddie Fisher. Although he made several movies, the performer was far more successful on the small screen than on the big one.

Liberace's appearance at the Hollywood Bowl in 1952 was the beginning of another Liberace trademark: elaborate clothes. Fearful he might get lost in the sea of black tuxedos worn by members of the Los Angeles Philharmonic, Liberace wore a custom-made white suit of tails.

Soon Liberace was spending a small fortune on flashy costumes. His elaborate costumes almost killed him in 1963 when he collapsed backstage after inhaling carbon tetrachloride, a cleaning chemical used on his soiled costumes.

Even though Liberace made his Carnegie Hall debut on September 25, 1953, his true home was not the concert hall, but the Las Vegas showroom. He opened the new Riviera Hotel in 1955, becoming the highest-paid entertainer in Vegas, with a weekly salary of $50, 000.

Liberace's enormous popularity and exposure made him the object of speculation and interest on the part of gossip columnists, who could hardly fail to note his fey mannerisms and effeminacy.

When he arrived in London for a 1956 appearance at Festival Hall, the Times of London noted that he was welcomed by over 3, 000 girls and young women and "some ardent young men."

When the London tabloid the Daily Mirror called him a "deadly, winking, sniggering, snuggling, chromiumplated, scent-impregnated, luminous, quivering, giggling, fruit-flavored, mincing, ice-covered heap of mother love" and "a sugary mountain of jingling claptrap wrapped in such a preposterous clown," Liberace sued for libel, stating that the tabloid insinuated that he practiced homosexuality, then a criminal offense.

In court, the performer repeatedly lied about his sexual life and thereby won the case. Liberace's lies about his sexual life may have been a calculated response to the virulent homophobia of the 1950s. One can hardly blame him for wanting to strike back at his persecutors.

Still, the lies established a pattern of denial and evasion that Liberace practiced for the rest of his life. In his four autobiographical books there is not a word of his homosexuality, which may suggest not merely discretion, but internalized homophobia.

In the 1960s, Liberace, now a fixture in Las Vegas, made his performances increasingly outrageous. In addition to the fantastic costumes, he made spectacular entrances, sometimes driving onstage in a custom car and then exiting by seeming to fly away.

In 1979, he opened The Liberace Museum in Las Vegas. It soon became the third most popular attraction in Nevada. It features eighteen of Liberace's thirty-nine pianos, numerous costumes, pieces of jewelry, and many of the performer's one-of-a-kind automobiles, including the "Stars and Stripes," a hand-painted red, white, and blue Rolls-Royce convertible.

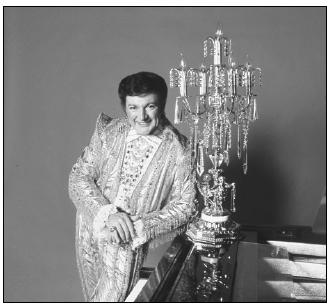

Liberace, promoting the The Liberace Show in 1969.

All of Liberace's efforts to maintain his closet collapsed when Scott Thorson sued the entertainer for $113 million in palimony in 1982. Dismissing Thorson as a disgruntled employee who was fired for alcohol and drug use, Liberace denied in court that the two had been lovers for five years. Ultimately, the matter was settled out of court for $95, 000.

Thorson, whom Liberace sent to a plastic surgeon to have Thorson's face remodeled in the performer's own image, was replaced by eighteen-year-old Cary James, who shared Liberace's life and bed until the performer's death five years later. James and Liberace both tested HIV-positive in 1985; James died in 1997.

In spite of his ill health and having lost fifty pounds, the sixty-seven-year-old Liberace honored his contract to appear at Radio City Music Hall in 1986, his third recordbreaking engagement there. Horrified by Rock Hudson's recent outing and death, Liberace steadfastly refused to disclose anything about his sexuality or health. He told close friends, "I don't want to be remembered as an old queen who died of AIDS."

Liberace died at the age of sixty-eight on February 4, 1987. He left the bulk of his estate to the Liberace Foundation for the Performing and Creative Arts.

Despite the railing of critics that he was a failed artist who debased music, Liberace remains popular: As of 1994, thirty-one new editions of his records had been issued since his death only seven years earlier.

Liberace was not only immortalized by a star on the Hollywood Walk of Fame, but by two television biographies: Liberace (ABC) and Liberace: Behind the Music(CBS), both in 1988.

—Bud Coleman

BIBLIOGRAPHY

Faris, Jocelyn. Liberace: A Bio-Bibliography. Westport, Conn.: Greenwood Publishing Group, 1995.

Hadleigh, Boze. Hollywood Gays. Barricade Books, 1996.

Liberace. An Autobiography. New York: G. P. Putnam's Sons, 1973.

_____. Liberace Cooks. New York: Barricade Books, 1970.

_____. The Things I Love. New York: Grossett and Dunlap, 1976.

_____. The Wonderful Private World of Liberace. Tony Palmer, ed. New York: Harper & Row, 1986.

Miller, Harriet H. I'll Be Seeing You: The Young Liberace. Las Vegas: Leesson Publishers, 1992.

Mungo, Ray. "Liberace." Lives of Notable Gay Men and Lesbians. New York: Chelsea House Publishing, 1995.

Pyron, Darden Asbury. Liberace: An American Boy. Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 2000.

Thomas, Bob. Liberace: The True Story. New York: St. Martins Press, 1988.

Thorson, Scott, with Alex Thorleifson. Behind the Candelabra: My Life With Liberace. New York: Dutton, 1988.

SEE ALSO

Popular Music; Cabarets and Revues

Lifar, Serge (1905-1986)

FROM RATHER UNPROMISING BEGINNINGS, SERGE LIFAR rose to the ranks of leading international ballet dancers and choreographers of the twentieth century. Although often dismissed as a derivative choreographer and a lessthan-stellar dancer by his many detractors, he parlayed the talent he possessed into a career that outlasted all his competition.

Fiercely ambitious, with a genius for positioning himself to exploit every opportunity that came his way, he used his extraordinary looks and charismatic personality to attract the attention of powerful supporters such as Sergei Diaghilev, Misia Sert, and Coco Chanel.

Born Sergei Mikhailovich Serdkin in Kiev, Russia, on April 2, 1905, the future dancer seemed to know from an early age that if the front door to the palace was slammed closed in his face, he could find other more welcoming entrances. In Kiev at the age of fifteen, he was rejected by Bronislava Nijinska as a student in her ballet school but persisted in his dream to become a dancer: He enrolled in the Kiev Opera Ballet, where Nijinska taught as well.

In 1923, Diaghilev asked Nijinska to summon five of her best male students from Kiev to join the Ballets Russes. At the last minute one of the five Nijinska choices was unable to make the journey, and Lifar leaped to fill out the quintet. Despite Nijinska's lack of enthusiasm for Lifar, either Diaghilev was helplessly drawn to the handsome eighteen-year-old or Lifar made certain that the master could not take his eyes off him.

Lifar's persistence, charm, and manipulation paid off by 1924, when, following private tutoring by the renowned ballet master Cecchetti, he was enlisted as the latest of Diaghilev's "favorites" (joining the long, distinguished list of dancer-lovers that includes Vaslav Nijinsky, Léonide Massine, and Anton Dolin, among others). As a result, he was cast in attention-getting roles and was groomed as a premier danseur and choreographer.

Despite grumbling in the company, Lifar had very real triumphs in Massine's Zephyr et Flore (1924) and Balanchine's La Chatte (1926).

Given an inch of acclaim, Lifar kept taking so much that even the world-devouring Diaghilev became exasperated at his extreme ambition and self-promotion. By that point, however, Lifar was indispensable as a star and the only choice for plum roles such as Apollo in Balanchine's history-making Apollon musagète (1928) and the title role in Balanchine's The Prodigal Son (1929).

Lifar's own first ballet, Renard (1929, to a score by Igor Stravinsky), though energetic and athletic, proved to be no masterpiece. His later work, however, demonstrated that he had learned much from Diaghilev, Balanchine, and Stravinsky.

After Diaghilev's death in August 1929, with the Ballets Russes in disarray, Lifar was not at a loss for long. Jacques Rouché of the Paris Opera Ballet invited him to star in a production in the tradition of Diaghilev to be choreographed by Balanchine.

As fortune would have it, Balanchine, ill with tuberculosis, had to withdraw from the project. Stepping in to fill Balanchine's shoes, Lifar established himself with authority as choreographer and star dancer at the premiere of Prométhée (choreographed to a score by Beethoven). He was soon engaged as the ballet master and director at the Paris Opera Ballet, where he remained in charge, with one significant interruption, until 1957.

During his tenure at the Paris Opera, Lifar was responsible for reviving the ballet in 1929, carrying on the Diaghilev tradition with productions of Ballets Russes classics, developing a strong presence for male dancers, and employing renowned choreographers such as Balanchine, Massine, and Frederick Ashton.

In his autobiography, Lifar coyly stated that "dance is my mistress" to avoid substantive revelations about his romantic entanglements with men and women of influence. But that statement pales next to his claim that his open socializing with the German High Command during the Occupation of Paris was related to his work as an undercover agent. Although the appearance of collaboration led to Lifar's "banishment for life" from the Paris Opera Ballet in 1944, he was back at work there by 1947.

Despite later upheavals such as his stormy exit from the Opera Ballet in 1957, Lifar's stature as a major force in international dance with a direct link to the great Diaghilev continued undiminished until his death in Lausanne, Switzerland, on December 15, 1986.

—John McFarland

BIBLIOGRAPHY

Buckle, Richard. Diaghilev. New York: Atheneum, 1979.

Garafola, Lynn. "Looking back at the Ballets Russes: Rediscovering Serge Lifar." Dance Magazine, October 1997, 74.

_____. "The Sexual Iconography of the Ballets Russes." Ballet Review28.3 (Fall 2000): 70-77.

Lifar, Serge. Lifar on Classical Ballet. Arnold L. Haskell, ed. London: Allan Wingate, 1951.

____. Ma Vie: from Kiev to Kiev, An Autobiography. James Holman Mason, trans. Cleveland: World Publishing Company, 1970.

____. Serge Diaghilev: His Life, His Work, His Legend, An Intimate Biography. New York: G. P. Putnam's Sons, 1940.

SEE ALSO

Ballet; Ballets Russes; Dance; Ashton, Sir Frederick; Béjart, Maurice; Diaghilev, Sergei; Nijinsky, Vaslav

Little Richard (Richard Penniman) (b. 1932)

SINCE ITS INCEPTION IN THE 1950S, ROCK AND ROLL has been considered a primarily white musical form, but one African American performer continues to be cited and, indeed, deferred to as the true architect of rock and roll: Little Richard.

Richie Unterberger has noted that Little Richard merged the fire of gospel with New Orleans rhythm and blues by pounding the piano and wailing with gleeful abandon. The over-the-top electricity of Little Richard's performances were compounded by his outrageous, genderbending appearance, replete with a six-inch stack of hair, eyeliner, pancake makeup, and flashy, attention-grabbing clothes.

In 1958, however, at the height of his career, Little Richard renounced his rock-and-roll lifestyle in favor of Fundamentalist religion. Since that time, he has continued to vacillate between show business and the church, while never losing sight of his profound influences on countless rock-and-roll performers. Despite his inner conflict, Little Richard has justifiably earned his status as a true musical legend.

Little Richard was born Richard Wayne Penniman on December 5, 1932, in Macon, Georgia, the third oldest of seven boys and five girls. According to Tony Scherman, though Richard's father, Bud, sold bootleg liquor, Bud and his wife, Leva Mae, were high-minded, proper people who were heedful of their children's welfare and hopeful for their future.

The Pennimans also had a family gospel group and Richard grew up steeped in the gospel tradition. At age fourteen, he adopted the stage name Little Richard and ran off to join one of the many itinerant medicine shows (traveling salesmen who plied customers with dubious cure-alls) that performed in small towns around the South.

Richard soon began performing at low-rent rhythmand-blues revues, where he learned to mix gospel fervor with blues lyrics. In 1951, Richard befriended flamboyant, openly gay R & B singer Esquerita, who taught him the pounding piano style for which he would become famous.

By 1955, after seeing his popularity increase dramatically, Little Richard made his way to New Orleans to record a demo tape that he sent to Art Rupe, president of Specialty Records, a small but successful Los Angelesbased rhythm-and-blues and gospel label. The tape ended up on the desk of Rupe's assistant, Bumps Blackwell, who immediately recognized the voice as star material.

Blackwell met Little Richard in New Orleans and, in a break from an otherwise frustrating studio session, watched as Little Richard began fooling around on the studio piano. The result was both electrifying and revolutionary. Little Richard tore into a slightly obscene ditty he had previously penned, and "Tutti Frutti" was born.

By January 1956, "Tutti Frutti" was number seventeen on Billboard's pop chart and number two on the R & B chart. It sold over half a million copies. Perhaps more importantly, it succeeded in bringing the races together, selling to both black and white youth.

Richard observed to his biographer Charles White, "The white kids had to hide my records 'cos they daren't let their parents know they had them in the house. We decided that my image should be crazy and way-out so that the adults would think I was harmless."

Richard quickly followed his initial success with a string of eight Top 40 singles including "Long Tall Sally," "Rip It Up," "Good Golly Miss Molly," and "Lucille," a raucous paean to a female impersonator.

In 1958, however, Little Richard's inner conflict between his sternly religious upbringing and his homosexuality boiled to the surface. According to Scherman, if Richard was a musical rebel, it may indeed have been because of his homosexuality, which he agonized over.

Even in his wildest days he carried a Bible, and read and quoted from it regularly.

On tour in Australia in the autumn of 1958, Little Richard hurled his diamond rings into Sydney Harbor, vowed to quit rock and roll, and on returning to the United States enrolled in Oakwood Bible College in Huntsville, Alabama.

Little Richard staged several comebacks over the years, but he never scored another Top 40 hit after 1958. He continues to seesaw between rock and roll and religion. He occasionally makes appearances on television and in movies, now better known as a colorful figure from the early days of rock and roll than taken seriously as a contemporary performer.

Nevertheless, Little Richard's seminal influence in the arena of rock music cannot be diminished. He remains a legendary and iconic figure in popular music. He continues to perform to appreciative audiences, and he was given further proof of his continued popularity when, in July 2003, he was inducted into the Songwriters Hall of Fame.

—Nathan G. Tipton

BIBLIOGRAPHY

Larkin, Colin, comp. and ed. "Little Richard." The Encyclopedia of Popular Music. Third ed. New York: Muze, 1998. 4:3270-3271.

Scherman, Tony. "Little Richard's Big Noise." American Heritage 46.1 (1995): 554-557.

Unterberger, Richie. "Little Richard."

www.allmusic.com/cg/amg.dll?p=amg&uid=UIDSUB040407070005211809&sql=Bp9508q9tbtm4

Vilanch, Bruce. "The Gay Race Card." Advocate, April 1, 1997, 57.

White, Charles. The Life and Times of Little Richard: The Quasar of Rock. Rev. ed. New York: Da Capo, 1994.

SEE ALSO

Popular Music; Rock Music; Blues Music; Bowie, David; Sylvester

Lully, Jean-Baptiste (1632-1687)

JEAN-BAPTISTE LULLY (1632-1687), though not the first to compose French opera, through his works established its basic principles. His influence on opera throughout Europe was immense, but his career declined as the result of a homosexual scandal.

The son of Italian peasants, Giovanni Battisti Lulli was brought to France in 1646 as an Italian tutor for Louis XIV's cousin Anne-Marie Louise d'Orléans, known to history as "La Grande Mademoiselle." His musical and acting abilities soon distinguished him, and, after the exile of Anne-Marie in 1652, he entered the king's service. He and the king danced in court entertainments, establishing a privileged relationship that led to the musician's quick advancement.

In 1661, Lully became a French citizen and was named Master of the King's Music. The following year, he married the daughter of Michel Lambert, a prominent singer and composer of vocal music at the French court. They had six children (three boys and three girls), and Lully seems to have been a good father and provider in spite of numerous extramarital activities with both men and women.

Lully collaborated with Molière, the greatest French comic dramatist, in creating plays with musical interludes and ballets. The two soon fell out, however, and Lully used his influence to prevent Molière from employing music in his works.

In 1673, Lully staged his first opera, Cadmus et Hermione. Fourteen more followed, including such works as Armide and Acis et Galatée; they established the pattern for French opera for decades to come.

Lully was ruthless in his pursuit of power and used his influence with the king to eliminate potential rivals through the establishment of monopolies over stage music. Perhaps as a result, his enemies spread stories concerning his sexual exploits. Almost certainly many of these stories were true, but Lully was discreet enough that the king could overlook his activities.

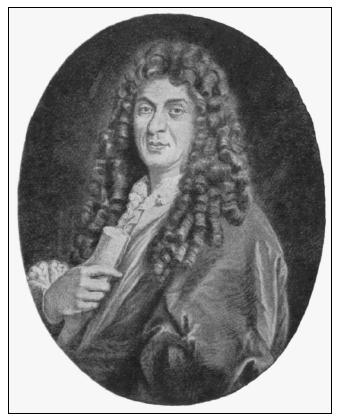

Jean-Baptiste Lully.

However, Lully's influence with the king evaporated in 1685 when he was involved in a scandal that the king could not ignore. The composer conducted an affair with a "music page" being trained in the royal service. This affair with a young man led to the composer's disgrace. Although he was not prosecuted, Lully was forced to break off the relationship and in addition lost his standing at court.

Homosexual activity was a capital offense in seventeenthcentury France, but the death penalty was only sporadically imposed. A number of the nobility at Versailles, including the king's brother Philippe, formed a homosexual subculture, and Lully had close ties with them. While the king disapproved of homosexuality, he loved his brother and was unwilling to exile, or otherwise punish, these nobles. At the same time, pressure was exerted by Louis's wife Madame de Maintenon and her priest to rid the court of sodomites.

Lully is said to have died by stabbing himself in the foot with a cane with which he was beating time at a rehearsal.

The wound resulted in blood poisoning and gangrene.

Beaussaint has argued that the story is apocryphal and that the composer, already in ill health, in effect died as a result of the king's abandonment.

—Robert A. Green

BIBLIOGRAPHY

Beaussant, Philippe. Lully ou Le musicien du Soleil. Paris: Éditions Gallimard, 1992.

Merrick, Jeffrey, and Bryant T. Ragan Jr., eds. Homosexuality in Early Modern France. A Documentary Collection. New York and Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2001.

Prunières, Henry. La Vie illustre et libertine de Jean-Baptiste Lully. Paris: Librairie Plon, 1978.

SEE ALSO

Classical Music; Conductors; Opera; Corelli, Arcangelo