m

Mathis, Johnny (b. 1935)

With more than sixty gold and platinum albums to his credit, Johnny Mathis is one of the most successful recording artists ever, trailing only Frank Sinatra and Elvis Presley in the number of albums sold. His interpretations of romantic ballads have brought him fame and wealth, but he is notoriously reticent about his own romantic life. Although he has acknowledged his homosexuality, he has refused to discuss it in any depth, and its effect on his art and life must remain speculative.

Born John Royce Mathis in 1935 in Gilmer, Texas, he grew up in San Francisco. The circumstances of his family were modest. His father, Clem, was a limousine driver and handyman, and his mother, Mildred, a domestic worker. Both parents encouraged him to develop the musical ability that he showed from an early age, but Mathis acknowledges in particular the role of his father.

When Mathis was eight years old, his father bought a used piano for him. The elder Mathis, who had been a vaudevillian in Texas, began to teach his son vaudeville routines, introduced him to the music of such singers as Lena Horne and Ella Fitzgerald, and urged him to participate in church choirs and talent contests.

When Mathis was thirteen, he met Connie Cox, an opera singer and voice teacher, who was so impressed with his singing that she offered to give him free voice lessons. He studied classical technique for six years and credits Cox with teaching him to sing the soft, high notes that are a signature of his style.

After high school, Mathis received an athletic scholarship to San Francisco State College (now San Francisco State University). He competed on the track team, setting a school record in the high jump. His impressive athletic performance earned him an invitation to participate in the 1956 Olympic trials.

The very same week, however, brought the opportunity to sign with a recording company. Mathis decided against trying to make the Olympic team but maintained an interest in his sport. He sponsors the Johnny Mathis Invitational track meet, which has been held annually at his alma mater since 1982. In 1997, SFSU chose him as the Alumnus of the Year.

During his college years, Mathis developed an interest in jazz and began to work in local clubs. When he appeared at the Black Hawk nightclub, Helen Noga, the co-owner of the establishment, quickly recognized his talent. She undertook the management of his career and secured bookings at more clubs in the area.

One such appearance, in 1955, at a San Francisco gay bar called the 440 Club, found George Avakian, a record producer at Columbia, in the audience. Although impressed with Mathis's potential, Avakian did not sign him immediately. He did, however, return to San Francisco the following year, at which time he offered Mathis a contract to record an album.

The debut album, Johnny Mathis, a New Sound in Popular Song (1956) did not do particularly well. The "new sound" was flavored with the jazz style of the music that Mathis had been performing in California. But he was soon to discover another sound that would propel him to stardom.

Following the release of the first album, Avakian brought Mathis to New York, where he continued working as a jazz singer, performing at various clubs and concert halls, including the Apollo Theater. But Avakian felt that Mathis needed to take a different direction to achieve greater commercial success. He therefore brought Mathis together with the producer and arranger Mitch Miller.

The pairing proved inspired. In collaboration with Miller, who was known for his lavish string arrangements, Mathis began singing romantic ballads. His first such recording, "Wonderful, Wonderful," was a Top 20 hit in 1957. He released five more extremely successful singles that year alone, including the chart-topping "Chances Are."

In 1958, he released an enormously popular album, Johnny's Greatest Hits, which held the number one spot on Billboard's pop chart for three weeks and remained on the chart for a record total of 490 weeks. The album included such standards as "The Twelfth of Never," "It's Not for Me to Say," and "Misty."

Mathis's career skyrocketed in the 1960s. He put out three or four albums a year throughout the decade and was much in demand on the concert tour. His rigorous schedule—with as many as 101 consecutive one-night shows—took a physical toll on him and caused him to become addicted to sleeping pills for a time.

In 1964, Mathis decided to take charge of his own career. He left his previous manager, Helen Noga, and started his own company, Rojon Productions. The break with Noga was rancorous, but they later reconciled their differences.

Mathis's albums of the 1960s and 1970s featured a variety of styles and material. On Olé (1965), he sang in Spanish and Portuguese. On albums such as The Long and Winding Road (1970), he covered the songs of other pop artists. He also recorded disco music. His albums sold millions of copies.

Singles by Mathis, on the other hand, tended not to make the pop charts. This changed in 1978, when his duet with Deniece Williams, "Too Much, Too Little, Too Late," became his first number one hit since 1957. It also brought Mathis, whose fan base had previously been primarily white adults, to increased attention among African American and younger audiences.

Following the success of his duet with Williams, Mathis recorded duets with several other singers, including Gladys Knight, Dionne Warwick, Natalie Cole, Barbra Streisand, and Nana Mouskouri.

Mathis's enchanting love songs have always appealed to the romantic side of his fans. Their effect on listeners has given rise to certain waggish comments, such as People magazine's "Mathis has often been blamed for the last 10 years of the baby boom." But his work appealed to gay and lesbian couples as well, many of whom may have intuited the singer's homosexuality.

Mathis's own love life, however, remained a mystery. He deflected interviewers' questions about his bachelor state until 1982, when he acknowledged his homosexuality in an interview in Us magazine. He spoke of his first love at the age of sixteen and said that being gay was "a way of life that [he had] grown accustomed to."

These disclosures had little if any effect on the public's perception of him; indeed, the public hardly seemed to notice them. In 1992, a group of gay activists attempted to out Mathis, only to discover that his sexual orientation was already on record. Mathis claimed that this had been unintentional. In 1993, he told an interviewer from the New York Times that he had intended the information divulged to Us magazine to be off the record. He has declined to make any further comments about his sexuality.

Mathis continues to pursue his career as a highly successful vocalist. Indeed, he is one of the most gifted interpreters of romantic ballads in the history of American popular music. After more than four decades in show business, he no longer tours as he once did, though he still gives concerts. He has performed at various charity events and at the White House.

He even had the chance to participate in two Olympic Games—as a singer.

—Linda Rapp

BIBLIOGRAPHY

Fitzpatrick, Laurie. "Johnny Mathis." Gay & Lesbian Biography. Michael J. Tyrkus, ed. Detroit: St. James Press, 1997. 311-313.

Gavin, James. "A Timeless Reminder of Back Seats in '57 Buicks." New York Times, December 19, 1993.

"Mathis, Johnny." The Guinness Encyclopedia of Popular Music. Colin Larkin, ed. New York: Stockton Press, 1995. 4:2749-2750.

Petrucelli, Alan W. "Celebrity Q & A," Us, June 22, 1982, 58.

SEE ALSO

Popular Music; Jazz; Faye, Frances

McPhee, Colin (1900-1964)

CANADIAN-BORN COMPOSER COLIN MCPHEE NOT ONLY helped preserve the musical traditions of Bali but also incorporated non-Western musical styles into his own compositions, a practice that influenced other North American composers.

McPhee was born in Montreal on March 15, 1900, but spent most of his youth in Toronto. He received his early musical education in Toronto and at the Peabody Conservatory in Baltimore.

In 1924, McPhee went to Paris to pursue his musical studies and his career as a pianist, but made little headway. After a year and a half he returned to North America to participate in the musical life of New York City—then an exciting center of modern music. Charles Ives, Edgar Varèse, Aaron Copland, Virgil Thomson, and Carlos Chávez were a few of the composers then contributing to the musical life of the city.

Sometime during the late 1920s, "quite by accident," McPhee happened to hear recordings of the gamelan music of Bali. "[A]s I played them over and over," he wrote, "I became more and more enchanted.... I returned the records, but I could not forget them. "He decided that he must travel to Bali to see the gamelan for himself.

Around the same time, McPhee met Jane Belo, who had studied anthropology and who was also interested in traveling to Asia. Although he was actively homosexual, McPhee and Belo were soon involved in an intense sexual relationship. They were married in 1930.

Belo was aware of McPhee's homosexuality, but she felt that a relationship with "a feminine man" was an important stage in her emotional development, and that it also revealed "aspects of masculine protest and narcissism" on her part.

In 1931, McPhee and Belo traveled to Bali. Once there, McPhee immersed himself in an exhaustive study of the Balinese gamelan—a percussion orchestra with delicately layered textures and clangorous sounds. He carefully studied how the instruments—gongs and bells, wooden xylophones, skin drums and bamboo flutes—were made as well as how they were played. He also carefully notated the melodic and percussive possibilities of every piece for gamelan he heard.

McPhee's research played a very important role in the preservation of the Balinese gamelan musical tradition, which was slowly dying. His musicological work Music in Bali (1966) is still the standard textbook at Bali's Conservatory of Music and Dance.

Since the Balinese were relatively tolerant of homosexuality, soon McPhee also threw himself into the sexual exploration of Balinese men. His sexual involvements with Balinese men led eventually to a separation from Belo.

McPhee wrote to one friend, "I was in love at the time with a Balinese, which she knew, and to have him continually around was too much for her vanity. So it ended as I had foreseen at the beginning..."

McPhee was able to live in Bali only because Belo had the money (which came from her family and her wealthy ex-husband) to do so. They were divorced in 1938, shortly before they both left Bali.

After almost seven years in Bali, McPhee returned to New York in 1939. Even before leaving Bali, he had begun to compose music that was an imaginative hybrid of Balinese and Western traditions.

His most important musical piece in this vein is his orchestral suite, Tabuh-Tabuhan. Composed in 1936 as a concerto for two pianos and large orchestra, it combines Balinese and jazz elements in the American style of Copland and Thomson. It premiered in Mexico City in 1936 under the baton of fellow composer Carlos Chávez; it received a standing ovation, but then languished without another performance until thirteen years later.

McPhee's next two decades in New York City were marked by financial hardship and slowly improving fortunes. In 1960, he moved to Los Angeles, and spent the last four years of his life teaching ethnomusicology and composition at UCLA. After two years of steadily deteriorating health from cirrhosis of the liver, he died on January 7, 1964.

McPhee's life is notable for three major achievements. Most important is that his musicological research on the gamelan helped to preserve Bali's musical traditions and contributed to the revival of what had been a dying musical practice.

Second, Tabuh-Tabuhan, his great work of musical synthesis, introduced a compositional style that incorporated non-Western musical traditions into Western concert music.

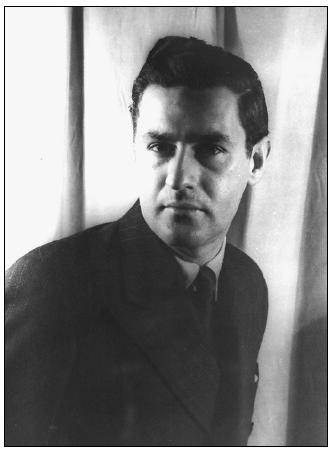

Colin McPhee, photographed by Carl Van Vechten in 1935.

Third, through his writing, his musicological research, and his example as a composer, McPhee helped to shape an entire American musical tradition carried on by composers such as John Cage, Lou Harrison, and Steve Reich.

—Jeffrey Escoffier

Bibliography McPhee, Colin. A House in Bali. New York: John Day, 1946.

—. Music in Bali. New Haven, Conn.: Yale University Press, 1966.

—. Tabuh-Tabuhan: Music of Colin McPhee. Sound recording. Toronto: CBC Records, 1997.

Oja, Carol J. Colin McPhee: Composer in Two Worlds. Washington, D.C.: Smithsonian Institution Press, 1990.

SEE ALSO

Classical Music; Cage, John; Copland, Aaron; Harrison, Lou; Thomson, Virgil

Menotti, Gian Carlo (b. 1911)

ONE OF THE LEADING CLASSICAL COMPOSERS OF OUR time, Gian Carlo Menotti not only has had a distinguished career, but also achieved acclaim at a time when his uncloseted homosexuality could have been a major barrier. Amazingly prolific and indefatigable, even in his nineties he continues to be a vital presence in the world of classical music.

Menotti was born in Cadegliano, Italy, on July 7, 1911. Although his family was not especially musical, they recognized their son's prodigious talent. Under the guidance of his mother, Menotti began to compose as a child. He wrote his first opera at the age of eleven.

He began his formal study of music at the Verdi Conservatory in Milan in 1923, but after the death of his father, he and his mother traveled to the United States, where he entered the Curtis Institute of Music in Philadelphia.

Menotti quickly adjusted to American culture and soon mastered the English language. He has spent most of his professional career in the United States and has written most of the libretti to his operas in English.

Among his fellow students at Curtis were composers Leonard Bernstein and Samuel Barber. Barber (1910-1981), with whom he was to share a relationship that endured more than thirty years, soon became his life partner, though Menotti later had a long personal and professional relationship with the conductor Thomas Schippers, as well. Menotti wrote the libretto for Barber's most famous opera, Vanessa (1964).

Avoiding the atonalism of the avant-garde school of Schoenberg and Webern, Menotti cast his lot with the popular tonal style of Schubert and Puccini, though he sometime used atonalism for dramatic effect in his operas.

Menotti's first mature work, the one-act opera buffa Amelia Goes to the Ball (1936), had its premiere in Philadelphia. It was subsequently staged at the Metropolitan Opera in New York, where it received popular and critical acclaim.

Menotti then wrote a series of operas that were staged very successfully on Broadway. The Medium (1945), The Telephone (1946), The Consul (1949), and The Saint of Bleecker Street (1954) established his reputation as the most popular opera composer in America. He received New York Drama Critics' Circle Awards and Pulitzer Prizes for The Consul and The Saint of Bleecker Street.

Menotti's Amahl and the Night Visitors was originally written for television and broadcast in 1951. It has since become a Christmas classic, performed all over the world during the Christmas season.

Most of Menotti's major successes as an opera composer came in the 1940s and 1950s. Since then, he has had a string of operatic failures and modest successes, including such works as Maria Golovin (1958), The Last Savage (1963), La Loca (1979), Goya (1986), and The Singing Child (1993). Some of these works will undoubtedly be restaged and reevaluated in the future.

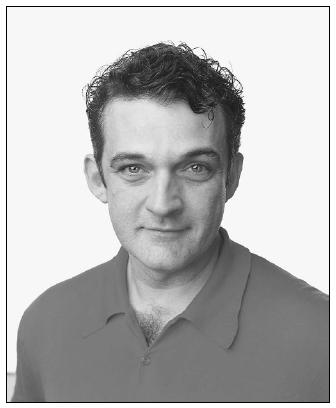

Gian Carlo Menotti, photographed by Carl Van Vechten in 1944.

In addition to opera, Menotti has composed orchestral and chamber works in various genres, including several solo concerti (his Piano Concerto is occasionally heard) and three tuneful ballets, of which one, Sebastian(1944), has enjoyed an extended life as a ballet suite.

One of Menotti's greatest triumphs has been The Festival of Two Worlds, which he established in Spoleto, Italy, in 1958. The festival, which is devoted to celebrating and encouraging the cultural collaboration of Europe and America, has become one of the most successful ventures of its kind.

In 1977, the Festival literally became "of two worlds" when Menotti founded Spoleto USA in Charleston, South Carolina. He led the Charleston festival until 1993, when he withdrew to become Director of the Rome Opera.

The composer continues to direct opera at Spoleto and elsewhere.

Menotti has sometimes been charged with extending himself too broadly and spreading himself too thin, as he has pursued a notably versatile career—composer of opera, orchestral works, and songs, director of opera, director of the Spoleto Festival, and so on. Still, he has achieved real distinction in many areas.

As a force opposed to the influence of the atonalism of the Vienna School, he has been an important figure in the music of his time. His compositions are written in a traditional tonal style and strive for melodic and harmonic distinction. Moreover, his music is comfortable for singers to sing and for audiences to hear.

Before gay liberation and before gay people could be completely candid about their liaisons, Menotti and Barber proved that gay men could have relationships that did not have to be closeted, though the term homosexual was rarely mentioned in public.

During the period of McCarthyism, with its homophobic persecution of queers in America, Menotti made a significant contribution to the cause of human liberation through his vivid example as an accomplished artist who was also an uncloseted homosexual.

Menotti began living in Scotland in the 1970s. He continues to reside there with an adopted son and his family.

—John Louis DiGaetani

Bibliography Archibald, Bruce, and Jennifer Barnes. "Menotti." The New Grove Dictionary of Music and Musicians. Stanley Sadie, ed. London: Macmillan, 2001. 16:432-434.

Ardoin, John. The Stages of Menotti. Garden City, N.Y.: Doubleday, 1985.

Gruen, John. Menotti: A Biography. New York: Macmillan, 1978.

SEE ALSO

Classical Music; Conductors; Opera; Ballet; Barber, Samuel; Bernstein, Leonard

Mercer, Mabel (1900-1984)

ALTHOUGH SHE NEVER ACHIEVED IN HER LONG LIFETIME the fame she so richly deserved, Mabel Mercer was one of the most respected singers of the mid-twentieth century, a most original stylist, and the toast of the New York cabaret scene.

Her career, which spanned seven decades, brought her to early fame in Paris, where she mingled with some of the most extraordinary gay and lesbian figures of the day, and in her later years she was a much-beloved icon of gay New York.

Mabel Mercer was born on February 3, 1900, in Burton-on-Trent, Staffordshire, England, to an English vaudeville singer and dancer. She was never to meet her father, an African American jazz musician who, according to some sources, died before she was born.

She was at first raised by her grandmother in Liverpool, and later educated at a Catholic convent school in Manchester. She left school at fourteen to join her mother, who had since married another vaudeville performer, as part of a touring company.

After the end of World War I, Mercer settled in Paris, where she met the celebrated Ada "Bricktop" Smith, an American singer and cabaret proprietor whose patrons included Gertrude Stein, Ernest Hemingway, and Zelda and F. Scott Fitzgerald. Mercer based her career at Bricktop's until 1938, when she fled in anticipation of World War II and the feared German invasion.

During her Paris years, Mercer became friends (and possibly more) with the notoriously eccentric lesbian heiress, speedboat racer, and womanizer Marion "Joe" Carstairs. Carstairs, who had settled in her own "kingdom"— Whale Cay, on an island in the Bahamas—paid Mercer's way across the Atlantic, fearing what the Nazis would do to the biracial singer.

Mercer resided in the Bahamas until 1941, when she married Kelsey Pharr, an openly gay African American musician, and obtained an entry visa from the United States government. The marriage was clearly one of convenience, as Mercer and Pharr never lived together and rarely saw each other; however, Mercer, as a devout Catholic, would not divorce Pharr, and they remained legally married, if in no other sense, until his death.

Upon her arrival in New York, Mercer began a series of engagements in some of the city's most elegant supper clubs and cabarets; and, for the rest of her life, the metropolis was her sole venue. Here she became the particular favorite of gay men, who found in her a sympathetic interpreter of their lives and loves, even when those lives and loves had necessarily to remain mostly closeted.

Mercer was a sophisticated interpreter of show tunes and standards, particularly those of Cole Porter and Noël Coward. Although often classified as a jazz singer, her style, which involved movement and gesture along with "proper" English-accented intonations, owed as much to the British music-hall tradition into which she was born as it did to le jazz hot of 1920s Paris.

Carstairs admired Mercer for being "ladylike," and this quality, along with her tremendous warmth and sly wit, made Mercer a completely unique talent. She considered each song a story to be narrated, not merely to be sung.

Her interpretations of standard songs, such as Coward's "Sail Away" and "Mad about the Boy," frequently captured qualities within them that other interpreters might have missed, especially the pain and sadness, as well as the pleasures and joy, of the lives of gay men in the 1940s and 1950s.

Mercer's recordings are few, and all date from later in her life. While those fortunate enough to have seen her perform live report that the recordings capture only a fraction of her appeal, much of which involved body language and audience interaction, the recordings nonetheless convey a joie de vivre and a personality not to be found elsewhere.

Although Mercer performed well into her seventies, she increasingly preferred the privacy of her country estate in rural New York, where she gardened, created recipes that were often published, and lived with her many pets.

She became an American citizen in 1952, and, in 1983, was awarded the Presidential Medal of Freedom for her contribution to American Culture.

She died quietly on April 20, 1984, in Pittsfield, Massachusetts.

—Patricia Juliana Smith

BIBLIOGRAPHY

Cheney, Margaret. Midnight at Mabel's: The Mabel Mercer Story.Washington, D.C.: New Voyage, 2000.

Haskins, James. Mabel Mercer: A Life. New York : Atheneum, 1987.

SEE ALSO

Cabarets and Revues; Popular Music; Jazz; Coward, Sir Noël; Porter, Cole

Mercury, Freddie (1946-1991)

FOR TWO DECADES, FREDDIE MERCURY WAS THE FRONT man of one of the world's most popular rock groups, Queen. That he was able to maintain this status in spite of continued critical hostility, his flamboyant genderbending androgyny, and questions about his sexuality is surely one of the more impressive accomplishments in the history of popular culture. He was also, arguably, the first Indian international rock star.

Freddie Mercury was born Farrokh Bulsara in the British colony of Zanzibar, East Africa (now part of Tanzania), on September 5, 1946. His parents were Parsees (Zoroastrian Indians of Persian descent), and his father was employed in the British civil service.

From the age of six, he attended boarding school near Bombay, India, and showed a considerable aptitude for art and music. It was here that he was first called "Freddie" by his classmates.

In 1964, the Bulsara family moved to England, where Freddie completed his education, graduating in 1969 from the Ealing College of Art with a diploma in art and design. Around this time, he adopted the surname Mercury, naming himself after the Roman messenger of the gods.

After college, he sold second-hand clothes in trendy flea markets, where he met future bandmate Roger Taylor, and joined Ibex, a local London group, as a vocalist and keyboard player.

In 1970, he formed a group with Taylor and Brian May (joined in 1971 by John Deacon), for which he chose the provocative name Queen. Even in its earliest days the band was notable for its stage performances, replete with light shows, flamboyant costumes, theatrics, and very high volume levels.

The group's first album, Queen (1973), was greeted with critical hostility, as were its early live performances, a result, no doubt, of the implied queerness of its name and Mercury's effeminate, long-haired, heavily made-up stage persona.

The group's breakthrough came the following year with the album Queen II, and the first big hit single, "Killer Queen," a tribute to a fabulous individual "just like Marie Antoinette" who may or may not have been female.

Within a year, Queen was one of the most popular bands in the world and began a series of world tours that drew crowds often in the hundreds of thousands. From 1975 until 1983, Queen enjoyed a long string of successful best-selling recordings.

These include "Bohemian Rhapsody" from the album A Night at the Opera (1975), "Somebody to Love" from A Day at the Races (1976), "We Will Rock You" and "We Are the Champions" from News of the World (1977), "Bicycle Races" and "Fat-Bottomed Girls" from Jazz (1978), "Crazy Little Thing Called Love" and "Another One Bites the Dust" from The Game (1979), and "Under Pressure" (with David Bowie, 1981).

In 1980, Mercury underwent a drastic image change that demonstrated his talent as a gender shape-shifter. Gone was the flaming, campy, "queeny" persona, replaced by a macho one, mustachioed, muscular, shorthaired, and attired in an undershirt and tight-fitting jeans.

The new image was not without its own camp elements, which many fans took at face value. Mercury nevertheless continued to confound gender assumptions, performing with the rest of the band in complete drag in the video "I Want to Break Free" (1984).

By the mid-1980s, Queen's popularity had peaked, and Mercury pursued a number of solo interests. His remake of the Platters' oldie "The Great Pretender" (1987), which suggestively begged the ongoing question of who or what was the "real" Freddie Mercury, proved a success, as did his compelling if unlikely collaboration with Spanish opera diva Montserrat Caballé, which produced the international hit "Barcelona" (1987).

During his lifetime, Mercury made no definitive statements about his private life or sexuality, leaving the interpretation of his public image up to the individual imagination; accordingly, many fans were shocked when events made some sort of revelation inevitable.

In Queen's early years, Mercury lived with a woman, Mary Austin, with whom he subsequently maintained a significant friendship; in 1980, however, they separated, and he lived thereafter until his death with Jim Hutton, supposedly his gardener.

On November 23, 1991, Freddie Mercury released a statement confirming that he suffered from AIDS, as had long been rumored. He died the following day.

Since Mercury's death, many tributes, including an AIDS benefit concert and a ballet choreographed by Maurice Béjart, have honored him. In 2001, he was posthumously inducted as a member of Queen into the Rock and Roll Hall of Fame. He has left a large and devoted following of fans.

—Patricia Juliana Smith

BIBLIOGRAPHY

Evans, David, and David Minns. Freddie Mercury: The Real Life, the Truth Behind the Legend. London: Antaeus, 1997.

Freestone, Peter. Freddie Mercury: An Intimate Memoir by the Man Who Knew Him Best. New York: Music Sales, 2000.

Hodkinson, Mark. Queen: The Early Years. New York: Omnibus, 1997.

Hutton, Jim, with Tim Wapshott. Mercury and Me. New York: Boulevard Books, 1994.

Jones, Lesley-Ann. Freddie Mercury: The Definitive Biography. London:

Hodder & Stoughton, 1997.

Smith, Richard. "A Year in the Death of Freddie Mercury: Queen." Seduced and Abandoned: Essays on Gay Men and Popular Music.London: Cassell, 1995. 234-239.

SEE ALSO

Popular Music; Rock Music; Music and AIDS; Béjart, Maurice; Bowie, David; Michael, George

Michael, George (b. 1963)

ALTHOUGH POP SINGER/SONGWRITER GEORGE MICHAEL began his musical career in 1980 as half of the queerly inflected pop duo Wham!, Michael's sexual orientation remained elusively undefined until 1998. On April 7, 1998, he was arrested for "lewd behavior" in a park restroom in Beverly Hills, California. Following his conviction, for which he was sentenced to perform community service, Michael confirmed his long-rumored homosexuality.

A week before the 1998 interview in which he formally came out, Michael met with Advocate editor Judy Wieder on the set of his music video "Outside." The video explicitly details (and parodies) the events surrounding Michael's arrest, including the resultant media frenzy. In his interview with Wieder, Michael addressed his contentious relationship with the press and the question of why he did not come out sooner.

He remarked, "If you tell me that I have to do something, I'm going to try not to do it. And what people don't understand in the equation of my relationship with the press is that I've had people talking and writing about my sexuality since I was 19 years old."

Born Georgios Kyriakos Panayiotou in London on June 25, 1963, Michael is the son of a Greek Cypriot restaurant owner. His family moved to the affluent London suburb of Bushey and, while in school there, Michael met Andrew Ridgeley, who became the other half of Wham!

In 1982, the duo won a contract with Innervision Records and, in the summer of 1982, released the album Fantastic, which became a hit in Britain. Their next album, Make It Big (1984), with its infectious single "Wake Me Up Before You Go-Go," exploded worldwide and cemented the pair's success but led to the accusation that Michael and Ridgeley were merely pretty-boy pop stars.

In 1986, at the height of their popularity, Michael and Ridgeley amicably dissolved Wham! and Michael forged ahead as a solo artist. In sharp contrast to Wham!'s "bubblegum pop" sound, Michael's first solo album, the Motown-inspired Faith (1987), featured songs with a much more soulful sound.

In addition to topping the pop chart, Faith also went to the top of the black album chart, making Michael the first white artist to achieve this honor. The album went on to win American Music Awards for Best Pop Male Vocalist, Best Soul/Rhythm and Blues Vocalist, and Best Soul/Rhythm and Blues Album, as well as the Grammy Award for Album of the Year.

One of the album's singles, "I Want Your Sex," reached number two on the American charts, due in no small part to its controversial content, widely interpreted as encouraging people to have sex in the age of AIDS. Michael, however, explained that the song's message promoted monogamy rather than promiscuity.

In 1992, he appeared at the Concert for Life, a benefit and tribute to Queen singer Freddie Mercury whose purpose was to increase AIDS awareness. The concert led to Michael's involvement in the album Red, Hot, + Dance, another project organized to raise funds for AIDS charities. In 1993, Michael released Five Live, a five-song EP (extended play, or shorter length LP/CD) featuring his Freddie Mercury tribute. All proceeds from the record went to the Phoenix Trust, an AIDS charity set up in Mercury's memory.

AIDS has been a particularly poignant charitable choice for Michael since the death in 1993 of his first boyfriend, Brazilian designer Anselmo Feleppa. The death spurred Michael to write a coming-out letter to his parents, who, according to him, were more concerned that he had just lost his partner than that he had actually finally said what they already knew.

Michael explained to Judy Wieder that AIDS not only changed his behavior but also helped him along his journey to honest self-discovery. For Michael's life and music, this self-discovery has been liberating and has led to a new sense of joy and triumph.

Michael's popularity seems only to have been enhanced by his coming out, despite the circumstances that forced him to be more honest than he intended. The music video "Outside" was well received and worked to defuse the controversy of his arrest.

Michael's most recent work, however, has not received the acclaim he expected. For example, his single "Freek" (2002) reached only number seven on the charts.

Moreover, in the summer of 2002 Michael found himself at the center of a firestorm prompted by the release in Britain of "Shoot the Dog," a video and song skewering the polices of President George Bush and Prime Minister Tony Blair in the wake of the war on terrorism.

When Americans complained that the song was an insult to the United States, Michael replied, "I am definitely not anti-American, how could I be? I have been in love with a Texan for six years." Michael's partner, Kenny Goss, is from Texas.

A musical artist of notable versatility, Michael emerged from the backlash that "Shoot the Dog" generated, but his vulnerability is indicated by the fact that the New York Post headlined its story about the song "Pop Perv's 9/11 Slur," which no doubt alluded to his homosexuality as much as to his arrest.

Despite this setback, two years later Michael once again reclaimed the pop music spotlight with the success of his critically acclaimed album Patience. Released by Aegean/ Sony Music in March 2004, the album represented what Billboard columnist Paul Sexton characterized as a "dramatic rapprochement for Michael and Sony Music," signifying the culmination of a successfully mended relationship between Michael and his record label.

Although immediately before the album's release Michael was quoted as saying that Patience would be his last major-label release, Sony executives are already planning Michael's next album, a duet record featuring four new collaborations, plus archived duets with Elton John, Whitney Houston, Queen, and others.

Michael, who was also reported to have said that, after Patience, he would quit the music business and release his songs free on the Internet, has apparently discovered that patience is indeed a virtue. His patience was further rewarded when, in May 2004, he was honored by U.K.- based PPL (Phonographic Performance Ltd.) as the most played artist on British radio in the past twenty years. In accepting the honor, Michael paid tribute to his early musical hero Elton John by telling the assembled gathering, "Without Elton John, there is no way I would be standing here. I used to dissect his records and obsess about song after song, and it was the beginning of my love affair with Pop."

After wild successes and equally notable failures, Michael has seemingly and finally found peace with both his homosexuality and his music.

—Nathan G. Tipton

BIBLIOGRAPHY

Hay, Carla. "By George, Radio Loves Him." Billboard, May 22, 2004, 35.

Larkin, Colin, comp. and ed. The Encyclopedia of Popular Music. Third ed. New York: Muze, 1998. 5: 3652-3653.

"The Official George Michael Website." www.aegean.net

Rampson, Nancy. "Michael, George." Contemporary Musicians: Profiles of the People in Music. Julia M. Rubiner, ed. Detroit: Gale Research, 1993. 9:169-172.

Sexton, Paul. "Strong Interest Precedes New Michael Album." Billboard, March 27, 2004, 9.

Wieder, Judy. "All the Way Out George Michael." Advocate, January 19, 1999, 24.

—. "Our Celebrities." Advocate, April 30, 2000, 42.

SEE ALSO

Popular Music; Rock Music; Music Video; Music and AIDS; Mercury, Freddie; John, Sir Elton

Minnelli, Vincente (1913-1986)

DAPPER VINCENTE MINNELLI WAS ONE OF HOLLYWOOD's greatest directors, renowned for his skilled use of color and light and his precise attention to detail. He achieved recognition not only for the new life he injected into movie musicals such as Meet Me in St. Louis (1944) and Gigi (1958), but also for emotionally complex comedies such as Father of the Bride (1950) and lushly conceived melodramas such as Lust for Life (1956).

Minnelli's campy vision and lavish productions were well suited to the 1940s and 1950s, but his style did not long survive the end of Hollywood's structured studio system. Although he continued to make films into the 1970s (such as A Matter of Time, with his daughter Liza Minnelli in 1976), his later films did not gain the popularity or acclaim of his earlier work.

Minnelli was born on February 28, 1903, in Delaware, Ohio, into a family of traveling entertainers. Although his early years were spent on the road learning show business, he settled in Chicago at age sixteen.

He took a job as a window decorator for Marshall Field's department store, where he began to develop his sense of design. He soon took his new knowledge back to the theater where he worked as an assistant photographer, costume designer, and set decorator. His originality and sharp eye for the details of design soon took him to the Broadway stage, where he was a successful costume and set designer.

Metro-Goldwyn-Mayer producer Arthur Freed discovered Minnelli on Broadway and brought him back to work his magic designing dance numbers for musicals at MGM. He worked on several films, including Strike up the Band (1940) and Babes on Broadway (1941) with Judy Garland and Mickey Rooney, before he was given the directorship of an all-black musical entitled Cabin in the Sky (1943). The stylish and inventive Cabin in the Sky was a success, and the window dresser from Chicago was now a Hollywood director.

Minnelli's next film, Meet Me in St. Louis, was a tour de force and a milestone in American filmmaking. Not only was it a textured look at turn-of-the-century Americana that spoke poignantly to a country in the midst of World War II, but it was also a showcase for Minnelli's flamboyant camera techniques and powerful use of color.

Meet Me in St. Louis was child star Judy Garland's first adult film. It led to the star's marriage to her director.

Although he married four times, Minnelli was widely known to be gay. In the deeply closeted world of 1950s Hollywood he kept his sexual orientation quite private, though his gay sensibility is visible in many of his films.

In his 1956 film version of Robert Anderson's exploration of masculinity and homophobia, Tea and Sympathy, Minnelli worked around the restrictions of the Motion Picture Association of America's production code to recreate the play's ambiguities without ever using the word homosexual.

In the little-noticed Goodbye Charlie (1964), Minnelli exploits the lighter side of gender confusion with a frothy comedy about a murdered womanizer who returns to earth in the body of a woman.

With the advent of a harsher realism in the movies in the 1960s and 1970s, Minnelli's dream sequences and fanciful use of color came to seem old-fashioned and out of date. He wrote his memoirs in 1974 and retired after the failure of A Matter of Time in 1976.

He died in Beverly Hills on July 26, 1986.

In 1999, Liza Minnelli premiered a tribute to her father called Minnelli on Minnelli, in which she performed many of the best-known and most beloved songs from his musicals, some of which had been made famous by her mother, Judy Garland, interspersed with loving reminiscences.

—Tina Gianoulis

BIBLIOGRAPHY

Gerstner, David. "Queer Modernism: The Cinematic Aesthetics of Vincente Minnelli." www.eiu.edu/~modernity/gerst-html

—. "The Production and Display of the Closet: Making Minnelli's Tea and Sympathy." Film Quarterly 50.3 (Spring 1997):13-27.

Harvey, Stephen. Directed by Vincente Minnelli. New York: Harper & Row, 1989.

Minnelli, Vincente, with Hector Arce. I Remember It Well. Hollywood, Calif.: Samuel French Trade, 1990.

Naremore, James. The Films of Vincente Minnelli. New York: Cambridge University Press, 1993.

SEE ALSO

Musical Theater and Film; Set and Costume Design; Edens, Roger; Garland, Judy

Mitropoulos, Dimitri (1896-1960)

IN THE 1950S, AT THE HEIGHT OF HIS SUCCESS AS CONDUCTOR of the New York Philharmonic Orchestra, composer Dimitri Mitropoulos became the subject of rumor and innuendo concerning the open secret of his homosexuality, in effect making him yet another victim of McCarthy-era homophobia.

For Mitropoulos, music was a lifelong passion. He delighted in exploring its richness and variety, and never hesitated to stage performances of works that other conductors found too challenging or complex. Twelve-tone music was his specialty.

A native of Athens, Mitropoulos took an interest in music from his earliest years. At around age six he carved himself a little wooden flute to play. A few years later, his parents provided him with piano lessons, at which he quickly excelled. His musical abilities brought him to the attention of a member of the faculty of the Athens Conservatory, who arranged for the boy to audit classes there and, when he was old enough in 1910, to enroll as a regular student.

Although Mitropoulos was devoted to music and had already composed a sonata for violin and piano while in his early teens, he planned on becoming a monk after completing his education. He was particularly drawn to the example of St. Francis of Assisi for his humility, gentleness, generosity, and respect for all others. Indeed, throughout Mitropoulos's life, he had a reputation as a sweet-natured man who shared the characteristics of his revered saint.

Mitropoulos gave up the thought of becoming a monk when his advisor in the Greek Orthodox Church informed him that no musical instruments were allowed in the monastery.

To please his father, who hoped that he would become either a lawyer or a naval officer, he briefly attended the law school of the University of Athens. It rapidly became apparent, however, that his vocation lay elsewhere, and he soon returned to the Conservatory, from which he graduated with highest honors in 1919. In addition, the faculty voted unanimously to award him a special gold medal.

During his last years at the conservatory, Mitropoulos began appearing publicly as a pianist, occasionally as an orchestral soloist. He also composed an opera, Soeur Béatrice, based on a play by Maurice Maeterlinck.

Although Mitropoulos had already recognized his homosexuality, he had a brief love affair in 1920 with Katina Paxinou, a drama student at the conservatory. The romance soon faded, but the two remained lifelong friends, exchanging frequent letters.

Paxinou, who came from a prosperous family, helped Mitropoulos stage his opera Soeur Béatrice in Athens in 1920. Among those who attended was composer Camille Saint-Saëns, who commented favorably on the work in an article published in a Paris newspaper.

Mitropoulos continued his musical education in Belgium and in Berlin, where he studied with Ferruccio Busoni, who inspired him to concentrate on conducting rather than composition.

On Busoni's recommendation Mitropoulos was chosen as an assistant conductor of the Berlin Staatsoper in 1921. Three years later, he returned to his native city to become the conductor of the Athens Symphony, a post he held for twelve years.

During his tenure in Athens, Mitropoulos was much in demand as a guest conductor and performed with most of the important orchestras of Europe.

His first trip to America came in 1936, when Serge Koussevitzky invited him to conduct the Boston Symphony Orchestra. His appearances there and in Cleveland and Minneapolis were enthusiastically received. Mitropoulos returned to the United States the following year to become the conductor of the Minneapolis Symphony Orchestra.

Mitropoulos was like nothing the staid midwestern town had ever seen. His vigorous and physical conducting style was uniquely his own. Until the last years of his life he eschewed a baton, instead energetically using his whole body to communicate with the musicians.

Sans baton, Mitropoulos was also usually without a score. His amazing ability to commit every detail of vast numbers of scores to memory was legendary.

Mitropoulos considered himself a missionary of music, and part of his mission was to bring new and challenging works to audiences. Soon after arriving in Minneapolis, he announced that each season would include at least three "intellectual concerts" with programs featuring modern composers such as Arnold Schoenberg, Paul Hindemith, and especially Gustav Mahler, whose music he greatly admired. The public response was wildly positive. Biographer William R. Trotter notes that by 1940 "Minneapolis...officially had the largest per capita concert audience in America."

Mitropoulos left Minneapolis in 1949 to share with Leopold Stokowski the duties of conductor and musical adviser of the New York Philharmonic Orchestra. The next year, Stokowski left, and Mitropoulos was named full musical director, a position widely perceived as the most prestigious in classical music in the United States. His tenure at the Philharmonic was marked by a number of signal successes, including a concert performance of Richard Strauss's opera Elektra during his first season and a presentation of Alban Berg's monumental atonal opera Wozzeck in 1950.

As he had in Minneapolis, Mitropoulos lived in modest lodgings in New York and avoided high-society parties. He also continued his habit of following the model of St. Francis when dealing with his musicians, leading through mutual respect and gentle persuasion rather than force and fear. The egos that he confronted at the Philharmonic made this approach problematic, however, and music critics began to carp that he was losing control of his orchestra.

Another element working against Mitropoulos was his sexual orientation, long an open secret in the music community. In the late 1940s and early 1950s, at the height of McCarthyism, it was not a good time to be known as a homosexual. Mitropoulos had always dodged questions about his bachelor status by claiming "I married my art" when queried by the press.

In a 1952 letter to a friend, Mitropoulos wrote, "for me music is another expression of my unlived sexual life." Trotter states that Mitropoulos did indeed lead a celibate life in both Minneapolis and New York, though perhaps "very occasionally" had sex on tour. In general, his "sexual drive [was] sublimated ruthlessly into his music-making."

Although true close friends—including the composers Ned Rorem and David Diamond—viewed Mitropoulos's existence as monkish, rumor and innuendo swirled around him, often fed by orchestra members and contributing to a lack of respect for Mitropoulos on the part of his players. Ironically, among those encouraging the whispers was the closeted Leonard Bernstein, who, since he was married, could present himself as the sort of "family man" that the orchestra wanted in the decade of conformity.

Bernstein got his wish, being named co-conductor with Mitropoulos for the 1957-1958 season and taking over as sole musical director the next. Typically gracious, Mitropoulos bowed out with praise for Bernstein's talent, but the loss of his position as director of this most prestigious American orchestra was deeply hurtful to him and a blow from which he never fully recovered.

He also mentioned his desire to devote more time to "that very tempting mistress, the Metropolitan Opera," which he had been conducting for several years and where he had recently staged a triumphant performance of Tchaikovsky's Eugene Onegin.

In the last years of his life, Mitropoulos undertook a demanding tour guest-conducting with European orchestras. The accumulated stress proved too great, however, and he suffered a fatal heart attack on November 2, 1960, while rehearsing Mahler's Third Symphony with the La Scala Opera House Orchestra in Milan.

Tributes poured in for Mitropoulos, not only for his prodigious musical abilities but also for his gentleness and decency as a person. "He was a dear, good man who was always so kind and full of understanding," commented the diva Maria Callas.

Mitropoulos is remembered for his extreme generosity. Throughout his life, he gave away nearly all his money, often to help struggling musicians and orchestras. In addition, during World War II he eschewed the opportunity to supplement his income by going on tour as a guest conductor, choosing instead to volunteer his time coordinating blood drives for the American Red Cross.

After Mitropoulos's death he was largely forgotten in the United States. One can only wonder if the lack of support from the musical community in New York contributed to this. In recent years, however, there has been renewed interest in his work, and many of his recordings have been reissued on CD so that they may be appreciated by new generations of music lovers.

—Linda Rapp

BIBLIOGRAPHY

"Maestro Mitropoulos Stricken in Milan, Dies." Washington Post, November 3, 1960.

"Mitropoulos, Dimitri." Current Biography 1952. Anna Rothe and Evelyn Lohr, eds. New York: The H. W. Wilson Company, 1953. 431-433.

Schonberg, Harold C. "He Lived for Music." New York Times, November 6, 1960.

Trotter, William R. "Mitropoulos, Dimitri." New Grove Dictionary of Music and Musicians. Second ed. Stanley Sadie, ed. London:

Macmillan, 2001. 16: 764-765.

—. Priest of Music: The Life of Dimitri Mitropoulos. Portland, Ore.: Amadeus Press, 1995.

SEE ALSO

Classical Music; Conductors; Opera; Bernstein, Leonard; Rorem, Ned; Saint-Saëns, Camille; Tchaikovsky, Pyotr Ilich

Molina, Miguel de (1908-1993)

MIGUEL DE MOLINA ROSE FROM POVERTY TO BECOME one of Spain's most celebrated flamenco singers. His wildly popular performances reinvented a dance and music tradition that had grown stale for lack of innovation and originality. Despite his success, however, Molina's open gayness and gender-bending stage persona provoked hostile reactions that plagued his career.

The naturally effeminate Molina was forced from the stage on numerous occasions and eventually found himself expelled from two countries. Yet, despite this homophobic persecution, Molina never retreated into the closet and refused to alter his feminine stage persona.

Molina's life was as melodramatic as his music. Born Miguel Frías in a small Spanish town near Málaga in 1908, he came from a background of dire poverty.

Expelled from school when a vengeful and sexually abusive priest accused him of "unnatural acts" with other boys, Miguel ran away to Algeciras, where he found employment cleaning a brothel. Because he was only thirteen at the time, the prostitutes cared for him as mothers and even arranged for a schoolteacher client to tutor him.

Moving on at the age of seventeen, Molina found employment on the ship of a Moroccan prince, serving in what was essentially the prince's male harem. The prince soon fell out of political favor, however, and Molina returned to Spain, where he began organizing Tablas Flamencas, or flamenco parties, for Granada's Gypsies.

This experience constituted Molina's first full exposure to a musical and dance tradition he already loved. By 1930, Molina arrived in Madrid, where he made increasingly good money organizing Tablas in the capital. One year later, he decided the time had come for him to take to the stage rather than to manage it. He appeared in a production of Manuel de Falla's ballet El amor brujo, but soon developed his own act, which combined flamenco and cabaret.

Molina's notion was to reinvent flamenco performance by feminizing the usual macho role taken by men. He sewed enormous two-meter-long sleeves, which he called blouses, onto the traditional costume and even sang the type of coplas, or popular songs, normally reserved for women.

Although he danced with a female colleague, he nonetheless acquired the name "La Miguela" and immediately met with enormous success. In 1933, he gave himself the name "de Molina."

With the outbreak of the Spanish Civil War in 1936, Molina fled to Valencia and from there entertained Republican troops. Because he and his dance partner Amalia Isaura became near mascots for the Levantine Republicans, both found themselves vulnerable after the Fascist victory in 1939.

Initially, a promoter closely connected to Franco's regime contracted them to tour the country. This arrangement protected the dancers from retribution, but in return they were paid a pitiful wage despite their popularity.

Tired of his status as war booty, Molina decided not to renew his contract once it expired in 1942. Soon thereafter, government thugs kidnapped him from the theater where he was then performing and tortured him, pulling his hair out and beating him with their guns.

Molina survived this abuse, but then suffered sequestration in remote Spanish towns. Unofficially banned from employment in Spain, Molina finally fled to Argentina, where he again met with great success. One year later, however, the machinations of Franco's government forced his expulsion from Argentina. Molina once again found himself in Spain without work.

In 1946, Molina fled to Mexico and soon thereafter settled in Buenos Aires, allegedly under the personal protection of Argentina's most powerful woman, Eva Perón. His customary success soon followed. Although he claimed not to have been political, his identification with Perónism caused many Argentines to despise him. In 1960, he withdrew from the entertainment world with some bitterness.

By the time he died in 1993, Molina had regained some of the esteem in which he had been held earlier, especially in Spain. He had, after all, produced numerous revues, starred in many films, and established two significant signature songs that most Spaniards know by heart, "Ojos Verdes" (Green Eyes) and "La Bien Pagá" (The Woman Well Paid).

According to Molina's not always reliable autobiography, the persecution he experienced at the hands of the Franco government had less to do with hostility from Franco's officials (with whom he enjoyed great popularity) than with the hatred and jealousy of a self-loathing, closeted gay functionary serving under the powerful minister of foreign affairs. Molina concluded that his nemesis begrudged him his openly gay, yet professionally successful life.

Serving Molina best through these tremendous setbacks was his unceasing creativity. By reinventing the role of the male flamenco dancer, feminizing his appearance and sound without rendering either "mannered," Molina attracted audiences well beyond the genre's traditionalists. Clothed in what seemed inverted dresses and singing songs normally reserved for women, he attracted even the roughest of soldiers to his flashy stage and movie persona.

Unfortunately, Molina never returned to live in Spain even after its transition to democracy.

—Andres Mario Zervigon

BIBLIOGRAPHY

Molina, Miguel de. Botín de guera. Autobiografìa. Salvador Valverde, ed. Barcelona: Editorial Planeta, 1998.

SEE ALSO

Dance; Cabarets and Revues; Falla (y Matheu), Manuel de

Morris, Mark (b. 1956)

MARK MORRIS IS ONE OF THE BEST-KNOWN AND MOST respected leaders in the dance world today. His works typically mix elements of Eastern and Western cultures and of the traditional and the avant-garde; they are set to a wide range of musical styles, from Baroque to rock, and frequently explore sexual ambiguities. No less an authority than Mikhail Baryshnikov has proclaimed Morris one of the greatest choreographers of his time.

Born on August 29, 1956, in Seattle, where he was raised, Mark Morris fell in love with flamenco at the age of eight when he saw a José Greco show. At thirteen, he joined a folk dance group, and later went to Spain intending to become a flamenco dancer. After a brief apprenticeship, Morris realized that flamenco was too limiting for him. He moved to New York when he was nineteen to pursue a career in modern dance.

During the early years of his career in New York, Morris performed with a variety of companies, including the Lar Lubovitch Dance Company, the Hannah Kahn Dance Company, the Laura Dean Dancers and Musicians, the Eliot Feld Ballet, and the Koleda Balkan Dance Ensemble.

Although Morris was primarily a dancer during his tenure with these companies, his ambition to choreograph led him to form the Mark Morris Dance Group in 1980. Founded in collaboration with friends and colleagues, the group had its first performance at the Merce Cunningham Dance Studio in New York.

Mark Morris.

Since then, Morris has created over 100 works for his company, as well as works for the American Ballet Theatre, the San Francisco Ballet, and the Paris Opera Ballet.

During the 1980s, the Mark Morris Dance Group gained increased recognition, performing at the Brooklyn Academy of Music's Next Wave Festival in 1984 and appearing for the first time at the Kennedy Center in 1985.

His works were often unpredictable and irreverent. The provocative program for a 1985 performance in San Francisco included The Vacant Chair, in which Morris appeared in his underwear with a brown paper bag over his head; and in Lovey, dolls are abused and ripped apart to the accompaniment of recordings by the Violent Femmes.

In 1987, while the Mark Morris Dance Group was working in Europe, choreographer Maurice Béjart retired as Director of Dance at Belgium's state opera house, taking the opera's ballet company with him. The opera's director, Gerard Mortier, recognized the potential of the Mark Morris Dance Group and offered Morris the position.

From 1988 to 1991, Morris served as Director of Dance for the Belgian National Opera in Brussels, bringing to Europe a distinctly American flair with such works as The Hard Nut (1988), his witty take on the classic Nutcracker, updated to the 1960s and set in a suburban American home, complete with vinyl furniture and a white plastic Christmas tree.

During the same period, Morris choreographed such works as the critically acclaimed L'Allegro, il Penseroso ed il Moderato (1988), with music by George Frideric Handel, and Dido and Aeneas (1989), a dance set to the baroque opera by English composer Henry Purcell. In the premiere of that work, Morris himself danced the dual roles of Dido, queen of Carthage, and the Sorceress.

When his contract with the Belgian National Opera expired in 1991, Morris and his company returned to the United States. They continue to make regular and frequent appearances throughout the country and in Europe.

Morris has also proved himself an accomplished director and choreographer of opera, most notably Orfeo ed Euridice (1996), by Christoph Willibald Gluck, and Platée (1997), a comic opera by Jean Philippe Rameau.

In 2001, the Mark Morris Dance Center opened in Brooklyn, New York. The new center provides Morris and his company a permanent space in which to create, rehearse, and teach.

—Craig Kaczorowski

BIBLIOGRAPHY

Covington, Richard. "The Dancer and the Dance: The Salon Interview with Mark Morris." Salon, September 9, 1996:

www.salon.com/weekly/interview960909.html

Gladstone, Valerie. "The Wizard of Dance." Town and Country, February 2001, 73.

Mark Morris Dance Company website. www.mmdg.org

Teachout, Terry. "Dance Chronicle: Going a Lot to the Mark Morris Dance Group." Partisan Review 67.2 (Spring 2000): 281-285.

Ulrich, Allan. "Mark Morris: 20 years of serious fun." Dance Magazine, April 2001, 44.

SEE ALSO

Dance; Ballet; Béjart, Maurice; Cunningham, Merce; Handel, George Frideric

Music and AIDS

ANUMBER OF MUSICAL WORKS IN VARIOUS GENRES have responded directly or indirectly to the AIDS crisis. Many musical works that refer to AIDS are about emotions, thus focusing on expressions of grief, anger, or sympathy, rather than on the personal and social consequences of the disease (as in novels, film, or drama) or on political confrontation (as in many works of visual art).

As a result, music about AIDS sometimes seems less specific than work in other media. Nevertheless, music of all kinds has registered the enormous impact of AIDS.

The earliest works appeared around the same time as the first AIDS plays, including punk songs by Karl Brown and Matthew McQueen for San Francisco's collaborative The AIDS Show ("Safe Livin' in Dangerous Times" and "Rimmin' at the Baths," September 1984).

The first commercially distributed music appeared soon after: Frank Zappa's "Thing-Fish" (November 1984), a satire of Broadway where abusive racial and sexual stereotypes people a demented tale of government conspiracy.

Much music about AIDS was written for fundraising purposes. An early and typical success was the vaguely sympathetic "That's What Friends Are For" by Burt Bacharach and Carol Bayer Sager (1985).

The benefit compilation Red, Hot + Blue (1990), in which contemporary pop artists cover Cole Porter songs, led to the foundation of the Red Hot Organization, which has since produced numerous CD and video anthologies. Notable Red Hot productions include the alternative rock collection No Alternative (1993), the sophisticated jazz/rap Stolen Moments (1994), and the hip-hop collection America Is Dying Slowly (1996).

Some major popular vocalists have made a point of performing songs about AIDS (usually one each), including Prince ("Sign o' the Times," 1987), James Taylor ("Never Die Young," 1988), Lou Reed ("Halloween Parade," 1989), Linda Ronstadt ("Goodbye My Friend," 1989), Elton John ("The Last Song," 1992), Madonna ("In This Life," 1992), Reba MacEntire ("She Thinks His Name Was John," 1994), Tori Amos ("Not the Red Baron," 1996), Patti Smith ("Death Singing," 1997), and Janet Jackson ("Together Again," 1998).

Most of these are written from the point of view of the survivor remembering a friend or an "outsider" developing sympathy for PWAs. Popular groups sometimes take a more complex approach, including the radical remix of "All You Need Is Love" by The JAMS (1987) or U2's eerie "One" (1992).

Some gay popular artists have not only specifically referred to AIDS but also explored the resultant emotional and social climate, especially Michael Callen and the Flirtations, Marc Almond, Jimmy Somerville, the Communards, and the Pet Shop Boys. The last group is known for songs that present their ironic, oblique view of 1990s gay life, including the discomforts of safe sex.

The most successful musicals that highlight AIDS have been William Finn's Falsettoland (1990) and Jonathan Larson's innovative Rent (1996), both of which engage gay characters with survivors at various stages of acceptance.

Other stage works, mostly in a soft-rock style, include Brian Gari's A Hard Time to Be Single (1991), John Greyson's sloppy but amusing Zero Patience (1994), Stephen Dolginoff's Most Men Are (1995), James Mellon's An Unfinished Song (1995), Cindy O'Connor's family study All That He Was (1996), The Last Session, by Jim Brochu and Steve Schalchlin (1996), and Elegies, by Janet Hood and Bill Russell (1996).

Some films about AIDS have notable music. For example, the soundtrack for Philadelphia (1993) included new songs by Bruce Springsteen and Neil Young. Bobby McFerrin created a vocal score for the AIDS Quilt documentary Common Threads (1989), and Carter Burwell wrote an orchestral soundtrack for And the Band Played On (1993).

The classical music community has produced a number of works, many of them neo-Romantic in style. The most important of these are John Corigliano's Symphony no. 1 (1990) and the ongoing AIDS Song Quilt (begun in 1992), created by baritone William Parker (1943-1993), which consists of a series of AIDS poem settings by composers including William Bolcom, Libby Larsen, and Ned Rorem. Younger composers such as Chris DeBlasio and Robert Maggio have made reputations partially on the basis of successful chamber works about AIDS.

Gay and lesbian choruses have performed many apposite works since early in the crisis, including reinterpretations of older songs. New cantatas written for them include Hidden Legacies, by Roger Bourland and John Hall (1992) and Naked Man, by Robert Seeley (1996).

The most important figure in avant-garde circles—probably the most important figure in music about AIDS— is vocalist/composer/performer Diamanda Galás. She has been creating works about AIDS since before the death of her brother, writer Philip-Dimitri Galás, in 1986. The most important of her works are the Plague Mass(1984) and the three-part Masque of the Red Death(1986-88), both of which exemplify her combination of savagely visceral texts with extraordinary vocalizations and complex musical textures.

Other women composers who have written avantgarde works include Meredith Monk (New York Requiem, 1993), Laurie Anderson (Love among the Sailors, 1994), and Pauline Oliveros (Epigraphs in the Time of AIDS, 1994).

Works by gay men include Gerhard Stäbler's Warnung mit Liebeslied (1986), Robert Moran's minimalist Requiem: Chant du cygne (1990), and Bob Ostertag's powerful All The Rage (1993), recorded by the Kronos Quartet.

Artist/writer David Wojnarowicz worked on many collaborative pieces, of which one of the most musical was ITSOFOMO, written with composer Ben Neill (1989).

The health crisis has directly affected the musical world as much as other areas of the arts. Among many musicians who have died are Klaus Nomi (1944-1983), Calvin Hampton (1938-1984), Sylvester (1947-1988), Freddie Mercury (1946-1991), Michael Callen (1954-1993), and Robert Savage (1951-1993).

Outside the urban West, protest and educational musics referring to AIDS have appeared in Mexico, South Africa, and (undoubtedly) many other countries. Limited distribution networks and language barriers have kept most from becoming available to English-speaking audiences. An exception is AIDS: How Could I Know?(1989), a bilingual recording produced by the Central Australian Aboriginal Media Association.

Despite the range of genres and works, there has been less music written about AIDS than there has been production in other art forms. This fact may be attributable to the strictures of the music industry, or to aspects of the nature of music.

Still, it is perhaps not too much to claim that the evident increase during the 1980s and 1990s in musical works that focused on grief, sympathy, or healing, some of which can be associated with "new age" music, is rooted in cultural changes that came out of the AIDS crisis.

—Paul Attinello

BIBLIOGRAPHY

Attinello, Paul. "Music and AIDS: Some Interesting Works." GLSG Newsletter 10.1 (Spring 2000): 4-6.

Avena, Thomas, ed. Life Sentences: Writers, Artists, and AIDS. San Francisco: Mercury House, 1994.

Baker, Rob. The Art of AIDS. New York: Continuum, 1994.

Dellamora, Richard, and Daniel Fischlin, eds. The Work of Opera: Genre, Nationhood, and Difference. New York: Columbia University Press, 1997.

Dunbar-Hall, Peter. "Rock Songs as Messages: Issues of Health and Lifestyle in Central Australian Aboriginal Communities." Popular Music and Society 20.2 (Summer 1996): 43-67.

Galás, Diamanda. The Shit of God. New York: High Risk, 1996.

Hughes, Walter. "In the Empire of the Beat: Discipline and Disco." Microphone Fiends: Youth Music and Youth Culture. Andrew Ross and Tricia Rose, eds. New York: Routledge, 1994. 147-157.

Hutcheon, Linda, and Michael Hutcheon. Opera: Desire, Disease, Death. Lincoln: University of Nebraska Press, 1996.

Jones, Wendell, and David Stanley. "AIDS! The Musical!" Sharing the Delirium: Second Generation AIDS Plays and Performances. Therese Jones, ed. Portsmouth, N.H.: Heinemann, 1994. 207-221.

Lee, Colin. Music at the Edge: Music Therapy Experiences of a Musician with AIDS. New York: Routledge, 1996.

McLellan, Jay. OutLoud!: Encyclopedia of Gay and Lesbian Recordings. First CD-ROM edition. Amsterdam: OutLoud Press, 1998.

Román, David. Acts of Intervention: Performance, Gay Culture, and AIDS. Bloomington: Indiana University Press, 1998.

Ward, Keith. "Musical Responses to HIV and AIDS." Perspectives on American Music since 1950. James Heintze, ed. New York: Garland, 1999. 323-351.

SEE ALSO

Musical Theater and Film; Corigliano, John; John, Sir Elton; Mercury, Freddie; Pet Shop Boys; Porter, Cole; Reed, Lou; Rorem, Ned; Somerville, Jimmy; Sylvester

Music Video

Music video, since its mainstream debut via the cable television network MTV in 1981, has been primarily a Top 40 music format. Gay and lesbian content within the standard three-minute constraint was rare in the early days, but with the advent of more openly gay, lesbian, and bisexual artists, that situation has gradually changed.

MTV and its sister station, VH1, which targets an adult contemporary audience, cater to popular tastes, and the production of music videos, an expensive promotional tool with virtually no other media outlet, has largely remained the reserve of major-label artists.

While the 1980s saw the rise of androgynous artists such as Annie Lennox of the Eurythmics and the openly gay transvestite Boy George of Culture Club, whose images were all over the airwaves, videos with specifically homosexual, nontheatrical characters were scarce.

One notable early exception is the work of heterosexual artist Bruce Springsteen, whose video for "Tougher than the Rest" (ca. 1988) features live concert footage interspersed with vignettes of couples made at venues on his "Tunnel of Love Express" tour. The video includes both gay and lesbian pairs interspersed with heterosexual couples as representatives of the artist's fans. Early on, Springsteen included this explicitly homosexual imagery with neither fanfare nor exploitation.

On the other hand, an ambiguity toward explicit sexual themes marks the content of many early videos produced by gay, lesbian, and bisexual artists. For example, Indigo Girls' first video, "Closer to Fine" (1989), depicts Amy Ray and Emily Saliers performing and singing with little or no interaction.

It was played on MTV (and later VH1), and the Grammy-winning duo became one of the first acts on the channel's emerging Unplugged program. At the time, Ray and Saliers were not closeted but neither were they out in the mainstream press.

The 1990s witnessed the beginnings of more deliberateness on the part of artists in depicting their own sexuality in their videos, yet this openness did not always translate into MTV or VH1 airtime, and sometimes led to censorship.

For example, 4 Non Blondes scored a huge radio and video hit with their 1991 song "What's Up," and while promoting the song the lesbian lead singer Linda Perry displayed a "dyke" sticker prominently plastered on her guitar for a performance on "Late Night with David Letterman"; but the group's video was merely a straightforward yet colorful depiction of alternative rock and roll with no reference to homosexuality at all.

Indigo Girls' video for "Joking" (1992), a montage of several sexually ambiguous people interacting and regrouping with one another, received virtually no airplay even though it explicitly deals with, in Ray's words, an "idea about androgyny within relationships and how a relationship is a relationship regardless of what sex you are."

Their 1995 video "Power of Two" opens with an image of male lovers embracing and includes both lesbian and heterosexual pairs throughout, but it received very limited VH1 play.

Lesbian chanteuse k.d. lang, who came out in the Advocate in 1992 and more spectacularly in a cover story in Vanity Fair in August 1993, has produced numerous videos that have played in heavy rotation on MTV and VH1, yet none include depictions of lesbianism.

Such is also the case with Melissa Etheridge, who came out nationally at an inaugural dinner for President Clinton in 1993. The videos for her blockbuster album Yes I Am (1994) include "Come to My Window," featuring actor Juliette Lewis, but none show lesbian relationships.

Tracy Chapman's number one hit "Give Me One Reason" from 1996 subtly implied that the singer was addressing the female bartender depicted in the video, though the narrative was resolved with a straight couple.

Also in 1996, bisexual singer Meshell Ndegéocello's video "Leviticus: Faggot," featuring a butch Ndegéocello (a woman) interacting with black gay men, was immediately banned upon its release, presumably because of its depiction, mirroring the song's lyrics, of parental gay bashing, faith-based opposition to homosexuality, prostitution, and suicide. Despite its initial censorship, the video is now available to view on Ndegéocello's website.

Among openly gay and bisexual male artists, Elton John has persistently adhered to a neutral mainstream aesthetic, a tactic used by many aging yet popular singers in which younger, attractive performers enact the video narrative while the star merely exudes his or her well-honed persona.

George Michael's post-coming out video "Outside" (1998) was an MTV exclusive. The video addresses Michael's homosexuality head-on through a parody of his arrest in a Beverly Hills park restroom on charges of soliciting a male undercover police officer. The video features Michael dancing around, dressed (Village People-style) as a macho cop, plus two other males dressed as cops kissing passionately. MTV played both a censored (blurred kiss) and uncensored (for late-night airings) version.

While the sometimes bisexual singer Madonna receives the most attention for her videos depicting bisexuality and homosexuality—from her cavortings with men and women in "Justify My Love" and "Music" to her remake of Don MacLean's "American Pie," in which gay men and lesbians are depicted kissing in unsensationalized moments—numerous other heterosexual recording artists, including Lenny Kravitz and Aerosmith, have upped the titillation factor in their videos by gratuitously depicting women together in sexual situations.

Singer Marilyn Manson resurrects Boy George by way of "Dope Show" (1999); like Michael's "Outside" video, "Dope Show" features a scene of males dressed as police officers in sexualized couplings while the overall video depicts the heterosexual Manson wearing an androgynous costume that features women's breasts.

As programming on video stations has begun to include fewer videos and more serial programs and films, the message from the video channels, if not from the artists, appears mixed.

In January 2000, MTV introduced its "Fight For Your Rights: Take a Stand Against Discrimination" campaign with the documentary Anatomy of a Hate Crime—Matthew Shepard. At the same time, the virulently homophobic rap artist Eminem won the MTV Video Awards Best Video of the Year for his song "The Real Slim Shady," which includes explicit slurs against gay men and lesbians.

—Carla Williams

BIBLIOGRAPHY

Cohen, Belissa. "Linda Perry Wants It All." Lesbian News, January 1997.

Indigo Girls. Watershed: 10 Years of Underground Video. DVD. Sony Music Entertainment, Inc./Epic Music Video, 1995.

John, Richard. "George Michael Video Parodies Arrest." Jam! Showbiz, November 2, 1998:

www.canoe.ca/JamMusicArtistsM/michael_george.html

lang, k.d. k.d. lang: Harvest of Seven Years (Cropped and Chronicled).VHS. Warner Reprise Video, 1991.

Springsteen, Bruce. Bruce Springsteen: The Complete Video Anthology: 1978-2000. DVD. Columbia Music Video, 2001.

www.sonymusic.co.uk/georgemichael/

SEE ALSO

Popular Music; Rock Music; Boy George (George O'Dowd); Etheridge, Melissa; Indigo Girls; John, Sir Elton; lang, k.d.; Michael, George; Village People

Musical Theater and Film

MANY WITHIN AND WITHOUT GAY CULTURE HAVE observed a strong identification on the part of gay men with musical theater. A number of gay writers have seen the musical as a crucial element in their consciousness of their homosexuality.

Alexander, Larry Kramer's alter ego in his play The Destiny of Me (1992), sings "I'm Gonna Wash That Man Right Out of My Hair" from South Pacific (1949) as a way of drowning out the attacks of his violent, homophobic father.

Queer critics Wayne Koestenbaum (The Queen's Throat) and D. A. Miller (Place for Us) write of their youthful love of the musical and its relationship to their sense of difference.

At the same time, television situation comedies have used love of musicals or knowledge of show tunes as a definitive sign of homosexuality. Even Kevin Kline's smalltown hero in the film In and Out (1997) listened to the cast album of Gypsy (1959) and worshipped Barbra Streisand.

In reality, such identification is stronger for men who grew up in an age in which musical theater was a more central part of American popular culture than it is now, a time when gay men necessarily had to find ways to sublimate their desires and identity. The flamboyant excess of musical theater, including opera and ballet, offered such outlets.

There are a number of ways to look at the relationship of the musical to gay culture, particularly gay male culture. One can consider the contribution of out or closeted gay composers and lyricists to the musical. Or one can focus on the importance of musicals—and, particularly, the centrality of the women who were its divas—to that group of gay men known as show queens. One could also look at post-Stonewall presentations of openly gay characters and shows written by gay writers primarily for gay audiences.

Composers and Lyricists

It is now common knowledge that some of the most important creators of the American and British musical have been gay men. One has to look only, for instance, at the men who brought Kiss Me, Kate to the stage in 1948, at the beginning of the Cold War, when treatment of homosexuals was particularly draconian.

This hit musical was produced by a gay man; written by Cole Porter, a gay man who was married but who rather openly and, for the time, incautiously, conducted his affairs with men; directed by John C. Wilson, who had been, in the 1930s, Noël Coward's lover; and featured among its stars the bisexual Harold Lang, who had affairs with Leonard Bernstein and Gore Vidal, among others.

Of course, none of this was common knowledge (except to people in the theater) at a time when homosexuality dared not speak its name; but it does suggest the ways in which gay men were invested in and responsible for musical theater.