v

Van Dantzig, Rudi (b. 1933)

AS ARTISTIC DIRECTOR AND RESIDENT CHOREOGRAPHER of the Dutch National Ballet from 1971 to 1991, Rudi van Dantzig brought his company to international attention with a repertory that embraced works of both classical elegance and modern energy. He has created a body of choreographic work that explores liberation, hope, and the place of homosexuality in our time, as well as such controversial issues as abuses of power.

Born in Amsterdam on August 4, 1933, van Dantzig was six years old when the German Army invaded the Netherlands. During the following five years, van Dantzig grew up under the Nazi Occupation, and for a particularly formative period was separated from his parents when he was sent to stay in the countryside, which presumably was safer from combat and bombing.

In his prize-winning autobiographical novel For a Lost Soldier (1991), van Dantzig recounts the harsh experiences of wartime from a child's perspective, including the story of a post-Liberation love affair between twelveyear- old Jeroen (the character standing in for van Dantzig) and a young (though significantly older than twelve) Canadian soldier who arrives with the Allied troops in 1945.

Running through the novel are themes of the loss of youthful innocence and the complexity of relationships in an atmosphere of aggression and fear. Not surprisingly, the same themes recur time and again in van Dantzig's choreography. (For a Lost Soldier was adapted in 1994 as a film of the same title, written and directed by Roeland Kerbosch.)

Classic adolescent problems, complicated by his wartime memories and premature introduction to adult sexuality, emerged after van Dantzig's return to Amsterdam. Uninterested in most of his schoolwork, he was a troubled student and dreamed of becoming a painter.

Then, one day, when he was fifteen, he wandered into a movie theater to be swept away by the film on view. The movie was not about a painter he might wish to become, however; the movie was The Red Shoes, Michael Powell's 1948 dance-filled masterpiece about a ballerina torn between a diabolical impresario and a struggling composer.

From that moment on, van Dantzig's sole obsession was to become a dancer. He studied first with Anna Sybranda before finding his way to the studio of Sonia Gaskell, a former Ballets Russes dancer who ran a small company and school in Amsterdam at that time.

By his own admission, van Dantzig was at a severe disadvantage since he had had no dance experience and was starting late. He was fortunate, however, as Gaskell overlooked his deficiencies and focused on his zeal and intelligence. Once he slipped into Gaskell's realm, van Dantzig worked hard, became a company member, and by 1955 had choreographed his first dance, Nachteiland (to a score by Claude Debussy).

Because Gaskell and her dance companies were dedicated to a classical and Diaghilev-style ballet repertory, he was not prepared for the impact that modern dance would have on him. Seeing his first Martha Graham performance hit van Dantzig like a bombshell. With a larger choreographic world opened to him by Graham's expressiveness and power, he traveled to New York to study her technique.

Upon returning to Amsterdam, the intense and mercurial van Dantzig became embroiled in disagreements with Gaskell and eventually decided to join ranks with Hans van Manen and Benjamin Harkarvy in 1959 to found The Netherlands Dance Theatre.

After a year with the new group, however, van Dantzig found himself dissatisfied and drifted back to Gaskell (whose company combined in 1961 with the Amsterdam Ballet to become the Dutch National Ballet). Upon Gaskell's retirement in 1968, he and another dancer, Robert Kaesen, took over the reins of the Dutch National Ballet; van Dantzig assumed the sole directorship in 1971.

Being in charge of the company suited van Dantzig. He possessed the rare combination of administrative ability and an unwavering drive to create powerful dances, such as Monument to a Dead Boy (1965, to a score by Jan Boerman), which created a sensation at its premiere.

Choreographed before van Dantzig shouldered administrative responsibilities, that piece explored innocence and corruption in homoerotic desire and offered the ballet superstar Rudolf Nureyev his first role in a modern work.

Critics may question the edgy elements of homoerotic tension and existential malaise that recur in van Dantzig's work, but they also appreciate the vigor with which he places his politics front and center without diminishing the theatricality of the dance.

Sans Armes, Citoyens (1987, to a score by Hector Berlioz) is one example of van Dantzig drawing inspiration from his complex personal life and extending it to address social issues through movement. Requiring ensemble dancing that demands great virtuosity, this piece is a virtual manifesto urging the ideals of Liberty, Equality, and Fraternity without resort to violence.

In its political and artistic vision, Sans Armes, Citoyens is emblematic of the more than fifty provocative works van Dantzig created before leaving the Dutch National Ballet in 1991. Since that time, he has devoted himself to writing and to staging his work with other companies.

—John McFarland

BIBLIOGRAPHY

Campbell, R. M. "On Stage at PNB Dance: Work from a Dutch Master." Seattle Post-Intelligencer, January 27, 1998.

Dantzig, Rudi van. For a Lost Soldier. Arnold J. Pomerans, trans. London: Bodley Head, 1991.

Klooss, Helma. "Dostoyevski of the Dance." Dance Magazine 67.11 (November 1993): 92.

Loney, Glenn. "Evolution of an Ensemble: Rudi van Dantzig on the National Ballet of Holland." Dance Magazine 48.3 (March 1974): 34-39.

Perceval, John. "The Voice of the People." Dance and Dancers 448 (May-June 1987): 32-34.

Utrecht, Luuk. "Rudi van Dantzig." International Encyclopedia of Dance. Selma Jeanne Cohen, ed. New York: Oxford University Press, 1998. 2:346-348.

---. Rudi van Dantzig: A Controversial Idealist in Ballet. Nicoline Gatehouse, trans. Zutphen, Netherlands: Walburg Press, 1993.

SEE ALSO

Ballet; Ballet Russes; Dance; Diaghilev, Sergei; Nureyev, Rudolf

Vargas, Chavela (b. 1919)

THE ACCLAIMED COSTA RICAN-MEXICAN PERFORMER and singer Chavela Vargas became notorious for the eroticism of her performances and for her open expression of lesbian desire.

Vargas was born Isabel ("Chavela") Vargas Lizano to Herminia Lizano and Francisco Vargas on April 19, 1919, in the province of Santa Bárbara de Heredia, Costa Rica, which is nestled between Nicaragua and Panama.

She grew up in Mexico, in exile, where she associated with leading intellectuals such as Frida Kahlo, with whom she had an affair, Diego Rivera, Agustín Lara, and Juan Rulfo, and even befriended political leaders such as Luis Echeverría, who served as President of Mexico from 1970 to 1976.

Vargas's career as a singer commenced in the mid-1950s, under the direction of José Alfredo Jiménez, her producer. Her first recording came a decade later, in 1961.

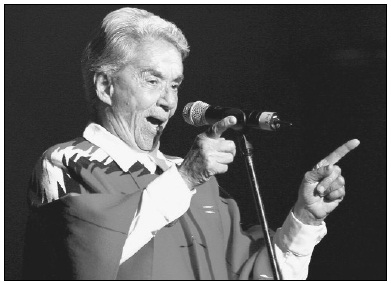

Chavela Vargas performs in the Port of Veracruz, Mexico, in 2003.

Photograph by Luis Monroy.

Vargas became famous in the mid-1960s for her hallmark interpretations, frequently melodramatic and heartwrenching, of sentimental Mexican songs. The originality of her style and the deep pain she was able to communicate marked her as a singular talent.

At the same time, however, she became infamous for her outlandish behavior, which violated a number of Mexican taboos. Not only did she wear trousers and dress as a man, but she also smoked cigars, carried a gun in her pocket, and sported a red poncho in her celebration and vindication of folklore.

A crucial element of her radical performance art was her seduction of women in the audience and her singing rancheras written to be sung by a man to a woman.

Vargas has come to be known as "the woman with the red poncho," as the Spanish singer Joaquín Sabina dubbed her, as well as "the queen of Mexican song." She shares this latter accolade with Mexico's greatest popular singers: Lola Beltrán, Angélica María, Juan Gabriel, Lucha Reyes, and Rocío Durcal.

For those intimately acquainted with her performances, Vargas is known simply as "La Doña" or "La Chabela." These epithets are signs of respect and reverence, which are extended to her despite her "black legend," which included a devastating bout with alcoholism as well as overt lesbianism.

Vargas's life has been dedicated to ritual performance that transgresses social, gender, and cultural borders through song. Perhaps because she was afflicted with illness in childhood—including polio and blindness that she declares were cured by shamans—she claims that she shares the stage with her own gods.

Through her long life, she has expressed a bold faith in spirituality and artistic expression—a faith that she has relied upon time and time again, especially when she has been labeled "other," "queer," and "strange."

After gaining fame in the 1960s, Vargas fell into alcoholism in the 1970s. She retreated from the public sphere for about twelve years. She attempted comebacks with only modest success, though she did sing in local cabarets, especially those frequented by gay men, who continue to constitute a large fraction of her admirers.

In 1981, however, she made a major comeback with stellar performances at the Olympia Theatre of Paris, Carnegie Hall in New York, the Palacio de Bellas Artes in Mexico, and the Palau de la úsica in Barcelona.

In the early 1990s, she experienced another revival. The gay filmmaker Pedro Almodóvar helped bring her a new audience by incorporating her bold, expressive, and seductive music into his films.

Vargas has recorded over eighty albums. Among her most notable and cherished titles and interpretations are "Macorina," "La China," "La Llorona," "Luz de Luna," "Toda una Vida," "Corazón Corazón," "Quisiera Amarte Menos," and "Volver Volver."

In November of 2000, the President of the Spanish government presented Vargas with "la Cruz de la Orden Isabel Católica," one of the most prestigious awards for artistic production.

This award, the singer declares, is a testament to her vexed legacy, one that includes her unapologetic persona and creative lesbian aesthetic.

—Miguel A. Segovia

BIBLIOGRAPHY

De Alba, Rebecca. "La 'leyenda negra' de Chabela Vargas." Diario Noroeste de Mazatlán, November 1, 2000.

EFE. "Chavela Vargas Clama Bienestar Social." Terra: arte y cultura, May 17, 2002.

Yarbro-Bejarano, Yvonne. "Crossing the Border with Chabela Vargas: A Chicana Femme's Tribute." Sex and Sexuality in Latin America. Daniel Balderston and Donna J. Guy, eds. New York: New York University Press, 2001. 33-43.

SEE ALSO

Cabarets and Revues

Variety and Vaudeville

FROM THE MID-NINETEENTH CENTURY ONWARD, A number of popular theatrical forms that included play on gender flourished in Britain, Europe, and the United States. The best known among these styles of theater, and the ones that flourished most in the United States, were minstrelsy, vaudeville (and its precursor, variety), and burlesque. All of these forms featured cross-dressed acts, as well as routines that challenged prevailing gender constructions.

In addition, certain performance specialties featured in some of these theatrical forms were known to attract homosexual performers. One of the difficulties in discussing sexual orientation in reference to performers of this period, however, is that the identity "homosexual" was relatively new and may well have been rejected by those whom we would now identify with this term.

On the other hand, there was a clear recognition by theater folks of this period that some performers were in same-sex or untraditional relationships. This recognition can be seen in snippets of gossip columns in theatrical newspapers that make oblique, usually snide, references to performers' private lives.

Many popular theater forms of the nineteenth century relied heavily on parody, stereotype, and novelty. Crossgender casting was one way in which serious drama or opera could be parodied. In all-male minstrel companies, cross-dressing was a necessity if female characters were to be included. And in forms such as British pantomime, which relied heavily on illusion and transformation, certain roles were purposely cast cross-gender.

Minstrelsy, burlesque, vaudeville, and variety were highly complex theatrical forms, and they all contained social commentary in addition to parodies of gender and gender constructions, but these parodies were a significant part of their appeal.

Minstrelsy

Minstrelsy emerged in the northeastern United States during the 1840s and flourished until almost the end of the century. After the Civil War, minstrelsy began to face competition from other popular forms such as burlesque, variety, and musical comedy. As Robert Toll notes, in order to compete with these rival forms a new role emerged within the all-male minstrel company—that of the glamorous female impersonator.

Indeed, in the United States minstrelsy can properly be regarded as the origin of glamour drag, and a number of prominent female impersonators of the earlier twentieth century—Karyl Norman and Julian Eltinge, for example—began their careers in minstrelsy.

Probably the best known of the early minstrel female impersonators was Francis Leon. Leon billed himself as "The Great Leon" and was featured in burlesque operettas staged by the Leon and Kelly Minstrel Company. Leon and his business partner, Kelly, maintained their troupe for five years, leasing a theater in New York City. Toll notes that by 1882 Leon was the highest paid minstrel performer and one of the most praised.

There were a number of other very successful female impersonators active in minstrelsy in the period, and reviews note that they sang in a believably female range.

The "prima donna" or "wench" role was not the only female role available to male minstrel performers. There was also a comic female role, the "Funny Old Gal," which was often performed by a large actor dressed in old and mismatched clothes.

This role was not unlike the comic cross-dressed roles for men found in burlesque, and similar characters were also found in the Irish comedies of Harrigan and Hart in the 1880s and later. This comic role was essentially parodic and relied on low comedy; these characters could be used to make fun of old women, unattractive women, unmarried women, and women advocating suffrage.

Burlesque

Burlesque is now most often associated with seedy strip shows and low comedy, but in the mid-nineteenth century this theatrical form was associated primarily with parody of high culture through puns, word play, and nonsense.

Burlesque in the United States was transformed by the tour of Lydia Thompson's British Blondes in the late 1860s. This troupe continued to use the standard formulae of burlesque, but they infused the form with sex. The actresses in this predominantly female troupe dressed in scanty costumes that showed their legs to the audience.

Burlesque always included cross-dressed roles, in keeping with the topsy-turvy world of this form. The "dame" role of burlesque was not unlike the "Funny Old Gal" role of minstrelsy, except that the costume was less ridiculous. Like the "Funny Old Gal," this role was also often played by a large actor who looked ridiculous in female attire.

One actor who won some fame in these roles was George Fortescue, who weighed well over 200 pounds. British pantomime provided similar comic female roles for men dressed as women—for example, the ugly sisters and the stepmother in the story of Cinderella.

Burlesque and also pantomime provided women with opportunities to play a number of male roles. Known as the "principal boy" and "second boy" roles, these characters were usually gallant young men who were still innocent to the ways of the world. The actresses who played these roles dressed in short tunics or pants, but retained their feminine curves and exposed the full length of their legs. There was no attempt to be realistically masculine.

Burlesque as it was performed by Lydia Thompson's troupe met fierce opposition in the United States, particularly from moral reformers. The feminist actress Olive Logan was horrified by the form, feeling that burlesque performances degraded theater as a whole. She described burlesque actresses as nude women and likened the troupe managers to pimps.

The role that excited the most opposition was that of the principal boy. Critics were disturbed by watching a woman who was clearly identifiable as such striding, swearing, spitting, and otherwise acting like a man.

Female Minstrel Companies

During the 1880s, burlesque and minstrelsy united in the form of female minstrel companies. This hybrid form consisted of a minstrel opening act performed by the women of the troupe, sometimes in blackface, sometimes not. A series of variety acts followed, and the entertainment was concluded with a burlesque.

With the advent of female minstrelsy, the emphasis shifted even more toward sexual display. Companies featured dozens of female performers who provided the audience with a mass display of scantily clad femininity. In most cases these women took nonspeaking roles, performing in the "Amazon chorus" or as a corps de ballet for suggestive dances such as the cancan.

Female minstrel companies were the forerunners of modern burlesque, with its heavy reliance on the female body and sexually suggestive performance.

Variety and Vaudeville

Variety first emerged in northeastern cities of the United States in the 1850s as formal and informal entertainment provided in bars. In its earliest days, this entertainment consisted mostly of singers hired to entertain the patrons and to lead sing-alongs.

By 1860, it had grown quite elaborate, and large concert saloons provided stage reenactments of current events as well as a succession of singers, dancers, and comedians. Patrons were also plied with drinks by "pretty waiter girls" who were hired to serve alcohol.

Authorities, alarmed by the rising number of these establishments, began to enact laws designed to put concert saloons out of business. As a response to changes in the law, and to ongoing harassment by the police, managers began to present what came to be known as variety in theaters rather than bars.

Variety was a theatrical form that could and did include almost any kind of act from performing animals to comedians to singers and dancers to one-act plays. It consisted of a series of acts unconnected by a narrative structure and concluded with a one-act play, usually a melodrama or burlesque.

It was considered the lowest class of popular forms, and individual acts rarely attracted much attention from the authorities or moral reformers unless they too obviously transgressed moral standards. Olive Logan considered variety to be a low and vile form of theater, but saw it as less of a threat to decency than burlesque because no one type of act dominated the stage.

A number of the kinds of acts featured on variety bills did challenge gender norms of the period, however. Female impersonators were present on the variety stage, though they were less common here than in minstrelsy or burlesque until the 1890s, when variety had come to be known as vaudeville.

Glamorous female impersonators appeared as solo acts, while the comic "Funny Old Gal" appeared in a number of variations. Comic depictions of women, often spinsters or widows, were common, as was the depiction of ethnic female types. The Russell Brothers, for example, performed a comedy routine as Irish cleaning women, and Harrigan and Hart performed an Irish act in which Tony Hart appeared as a woman.

A number of glamorous female impersonators won fame in vaudeville in the early twentieth century. Among these were Julian Eltinge, Bothwell Browne, Karyl Norman, and Barbette.

Barbette performed an acrobatic and wire-walking act in female costume. It was not at all uncommon in the late nineteenth century for young male acrobats to perform dressed as girls—the audience was apparently more appreciative of feats of daring from young women. Barbette was widely known as homosexual, and such was reputed to be the case with many circus acrobats.

Julian Eltinge and Karyl Norman both began their careers in minstrelsy and later moved to vaudeville. Although their sexual orientations are not known, neither man was married.

In nineteenth-century variety there were also acts featuring women dressed in male costume. Sister acts featuring one sister dressed as a girl and the other as a boy were common into the twentieth century. Acts such as the Foy Sisters or the Richmond Sisters sang light sentimental songs in duet. This style of male impersonation was closest to that found in burlesque, with less emphasis on sex appeal and more on sentiment.

Variety also featured realistic male impersonators who sang in a believably male range. These were women who were masculine in appearance and dressed in the height of male fashion. They shared their repertoire and performance style with male performers. Among the most successful of these women were Annie Hindle, Ella Wesner, and Blanche Selwyn.

While these women had largely been forgotten by the end of the century, they were among the highest-paid variety performers of the 1870s and 1880s, earning as much as $200 a week. They depicted a wide range of masculinity in their acts and were extremely popular with all-male working-class audiences because their acts mercilessly parodied middle-class values, while glorying in the excesses of leisure—alcohol, women, and fine fashion.

By the beginning of the twentieth century, this style of male impersonation had disappeared and male impersonators were more feminine in appearance and were generally sopranos.

Other kinds of acts in variety also challenged prevailing gender constructions. Among these were acts such as the "double-voiced vocalist," which could be performed by either a man or a woman. The performer was often dressed in a costume that combined male and female clothing—one half male, one half female.

One performer active in the 1870s was Dora Dawron, who sang both soprano and baritone and turned the appropriate side to the audience as she sang. Karyl Norman also performed a double-voiced act, alternating between male and female characters and changing costume between songs.

Female strongwomen were also featured on the stage, and the audience delighted in watching women do the impossible—lifting weights and furniture and even people. Female multi-instrumentalists also challenged gender norms, as young women played instruments usually reserved for men, such as trumpet and saxophone and banjo. Because variety relied heavily on novelty, women performing such unfeminine feats of strength and skill were often very popular.

—Gillian Rodger

BIBLIOGRAPHY

Allen, Robert. C. Horrible Prettiness: Burlesque and American Culture. Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 1991.

Bean, Annemarie, James V. Hatch, and Brooks McNamara, eds. Inside the Minstrel Masks: Readings in Nineteenth-Century Blackface Minstrelsy. Hanover, N.H.: University Press of New England for Wesleyan University Press, 1996.

Kibler, M. Alison. Rank Ladies: Gender and Cultural Hierarchy in American Vaudeville. Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 1999.

Logan, Olive. "About the Leg Business" and "About Nudity in Theatres." Apropos of Women and Theatres, With a Paper or Two on Parisian Topics. New York: Carleton, 1869. 110-153.

Lott, Eric. Love and Theft: Blackface Minstrelsy and the American Working Class. New York: Oxford University Press, 1993.

Rodger, Gillian. Male Impersonation on the North American Variety and Vaudeville Stage, 1868-1930. Ph.D. diss., University of Pittsburgh, 1998.

Snyder, Robert. The Voice of the City: Vaudeville and Popular Culture in New York. New York and Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1989.

Toll, Robert C. Blacking Up: The Minstrel Show in Nineteenth-Century America. New York: Oxford University Press, 1974.

SEE ALSO

Cabarets and Revues; Drag Shows: Drag Queens and Female Impersonators; Drag Shows: Drag Kings and Male Impersonators; Hindle, Annie

Village People

The Village People were a disco-era singing group formed in the late 1970s. Although the group never identified itself as gay, its primary appeal was clearly to a gay male audience. It successfully translated the interests, coded language, and iconography of the gay male subculture into music that crossed over into mainstream pop.

Because the general public was largely unaware of the meanings and suggestiveness of the lyrics or the costumes associated with the group, the gay audience not only enjoyed the music on its own terms, but also relished the irony of a mainstream audience unknowingly embracing subculture values and images.

The Village People were formed in 1977 by French record producer Jacques Morali, who was inspired to create the group after seeing performer Felipe Rose, dressed as a Native American, singing and dancing in the streets of Greenwich Village. Hence the group's name.

Morali approached Rose about forming a group and then, with his partner Henri Belelo, auditioned other singers by advertising in trade publications for "singers with mustaches."

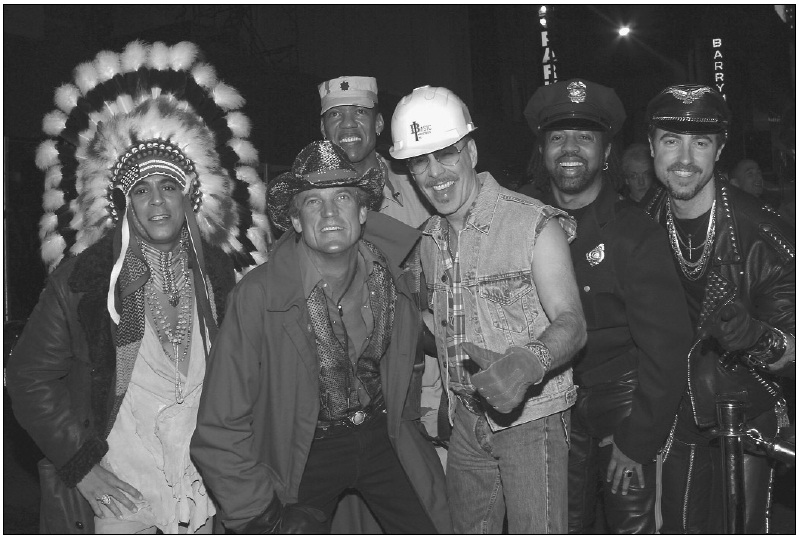

All members of the group performed in costume to represent masculine (and, not coincidentally, gay male fantasy) archetypes: the Native American Rose, construction worker David Hodo, policeman Victor Willis, soldier Alex Briley, cowboy Randy Jones, and biker/leatherman Glenn Hughes. Rose was openly gay, but the other singers never discussed their sexual orientation.

Regardless, the Village People's core audience was undeniably gay men, and their most popular hits were overtly homoerotic.

"YMCA" (1978), for example, told its presumably male audience about the delights of staying at the YMCA with other young men; "In the Navy" (1979) sang the joys of being in the Navy with other young men; and so on.

The group's other major hits included "Macho Man" (1978), "Fire Island" (1977), and "Go West" (1979). Three of their albums went gold (selling more than 500 thousand albums) and four went platinum (selling more than one million).

The Village People starred in a largely fictionalized film version of their origins, Allan Carr's Can't Stop the Music (1980), which featured blatantly homoerotic production numbers. One of the most memorable took place in a gym and involved a large number of muscular men going through Busby Berkeley routines to the tune of "YMCA." Although critics savaged the film, it has gone on to achieve a certain status as a camp classic.

Several of the Village People's albums were released only in Europe, where they had a large and faithful following. Their third album released in America, Renaissance (1981), was their attempt to reinvent themselves as a New Wave 1980s group, after the decline of disco. The album was a commercial flop, and the Village People disbanded from touring in 1986. Morali, the group's founder and creative director, died of AIDSrelated illnesses in 1991.

Never taken particularly seriously (musically or otherwise), the Village People nevertheless remain one of the enduring legacies of 1970s gay male popular culture. They regrouped in 1998, with three of the original singers and three replacements (Jeff Olson as the cowboy, Ray Simpson as the cop, and Eric Anzalone as the biker/ leatherman). They continue to tour, performing both their early hits and new material as well.

—Robert Kellerman

BIBLIOGRAPHY

"A Straight Road to Gay Stardom." Maclean's, April 24, 2000, 9.

"With a Bump, a Grind and a Wink, Disco's Macho Men are Time-Warp Wonders." People, June 17, 1996, 60.

SEE ALSO

Popular Music; Disco and Dance Music; Pet Shop Boys; Sylvester

The Village People, photographed by Alecsey Boldeskul/NY Photo Press in 2003.