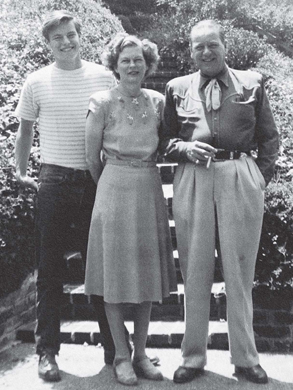

With my parents in front of our house in Bel-Air. (COURTESY OF THE AUTHOR)

There’s no bastard like a German bastard, and by all accounts my grandfather Mathias Wagner was a nasty man. He was a stevedore in Mannheim, Germany, where Wagner is a very common name. He came to America in 1876 and found that he needed a wife, so his relatives in Germany sent him some pictures of local German girls who wanted to come to America. Two of the girls in the pictures were sisters; my grandfather picked one sister, and his best friend picked the other. And that’s how my father was born: as the result of an arranged marriage.

Robert J. Wagner, my father, was born in Kalamazoo, Michigan, in 1890, but he left home when he was ten years old. I have no doubt he was abused; the Germans of that era would punch their children in the face just to let them know who was boss. My father said that his mother, a glorified mail-order bride, had no say in anything. She was more like a hired child-care worker than a wife.

My dad spent his adolescence selling newspapers on the streets of Kalamazoo, working in railroad stations, in bars, wherever there was a paying job. Because he was so estranged from his parents, I never knew them. My grandfather died early, and by the time I met my grandmother, she had developed dementia, so there was no way to establish a relationship.

My parents met on a blind date in Chicago. My mother’s name was Hazel Alvera Boe, which was always a sore spot with her. She hated the name Hazel, so everybody called her “Chat,” because she was so talkative. In time, I would call her “C,” while her pet name for me became “R.” She was a telephone operator when she met my father, and he was selling fishing tackle. Before that, he’d been a traveling salesman who sold corsets, petticoats, and other women’s undergarments wholesale throughout the Great Lakes region.

A few years after they met, he was in a hardware store where a guy was mixing a can of paint. My father liked the look of the surface it gave. He found out about the paint company, which was called Arco, and then he found out the name of Arco’s president, and he became a salesman for that paint. (Needless to say, my father was a go-getter.) He ended up getting the Ford Motor Company account; he sold most of the lacquer that was applied to the dashboards of Ford cars, and in short order he became very successful. Besides that, both before and after his Ford period, he bought and sold lots around the Palmer Woods area of Detroit. He would build houses, and my mother would decorate them.

My father was the sort of man who was obsessed by his business, and even after his kids arrived—my sister, Mary Lou, in 1926, me on February 10, 1930—that never changed. I was christened Robert John Wagner Jr., but since my father answered to “Bob,” and nobody, especially me, wanted me to be known as “Junior,” I became known as “RJ,” which my friends call me to this day.

Mary Lou was the valedictorian of her class, but she wanted a quiet, domestic life, and she got it. She’s a wonderful woman, with a totally different life than mine. She’s had five children and numerous grandchildren. She’s lived in the same house in Claremont for decades and doesn’t venture out that much.

When I was a small child, we all lived in a beautiful house on Fairway Drive, right off the Detroit Golf Club, but the best times with my father were summers in the Upper Peninsula of Michigan, where he had a cabin on a lake. I vividly remember riding through meadows on horseback with my father and uncle. There were no sounds except the whisk of the grass as the horses moved through it, and at night the moon was so bright you could read by it. It seemed like we were the only people alive, and I basked in my father’s undivided attention. It was during these times that he taught me how to fish—probably his greatest, longest-lasting gift to me. These were weeks out of Hemingway’s Nick Adams stories, and they are my most cherished memories of early childhood.

Also rewarding was the family Christmas, during which my parents went whole hog in spite of the fact that they had an arm’s-length relationship with religion. Technically, my father was a Catholic, not to mention a thirty-second-degree Mason, while my mother was a Unitarian, but I don’t even know if they bothered to baptize me. They sent me to Episcopal schools, and they sent me to Catholic schools, but we hardly ever attended church as a family, and they simply didn’t impose much religion on me. On balance I’m glad—my lack of indoctrination has resulted in a very open attitude toward the different religious factors that motivate people’s lives.

Although my father hated my grandfather because of his abusive behavior, my dad was never able to entirely free himself from his upbringing. If I did something mildly wrong, he’d stand me in a corner. For something worse, he’d lock me in a closet. If I did something deemed beyond the pale, I would be hit. When I was little, I stuck something in an electrical socket and blew out every outlet in the house. My father was in the bathroom shaving, and he came roaring out, grabbed me, put me over his knee, spanked me with a hairbrush, then threw me off his lap for this terrible thing I had done.

All this was the custom of that time; there was an attitude that corporal punishment was acceptable, and this was how a lot of the kids who grew up with me in Detroit were raised. I don’t think it’s any accident that a lot of those rich kids ended up wasting their lives or even killing themselves. The parents had their cars, their houses, a nurse, a chauffeur, white tie and tails, and the children were expected to conform to that model without question.

There was a sense that the children were possessions, and it was no accident that I carried the same name as my dad. From the time I was six, I was sent to camp regularly; a year after that, I was addressed and sent to Hollywood at the age of seven. Literally. My father took me to the train station in Detroit and tipped the porter $10 to make sure the package—his son—arrived safely. On my coat was a tag: “Deliver this boy to Mrs. Pierce, Hollywood Military Academy, Hollywood, California.”

As soon as the train pulled out from the station, I ripped the tag off my coat. Now that I look back on it, the entire business with the tag—my father giving orders, me ignoring them as soon as he was out of sight—was a fairly accurate preview of our entire relationship.

My father had opened a checking account for me so that I could pay my expenses on the trip. I remember that in Albuquerque I went into a souvenir shop and bought an antique gun so I could protect myself against the marauding Indians I was sure would attack the train at some point. (Obviously, the movies had already gotten hold of me.)

On the one hand, my father was force-feeding me a very valuable sense of independence. He was also telling me that the world wasn’t all that dangerous and that you could survive if you only had a firm destination in mind.

On the other hand, you might ask why a seven-year-old would be sent away from his home in the first place, and the answer would be that my parents had a social life that was very important to them. I always had the vague feeling that I was an encumbrance, something to be brought out on holidays and other occasions marked “Family,” and then promptly filed away somewhere else, somewhere out of sight.

I resented this then. I resent it now.

That first year in California was strange. While my parents were building their house in Bel-Air, my sister and I were both in boarding schools—I was at the Hollywood Military Academy, and Mary Lou was at Marymount—and we only saw each other on weekends. Both of us suffered from the loss of Margaret Maleski, a warm, nurturing woman who had done much of the work of raising us back in Michigan. Not having Margaret around, not having anyone to give us unconditional love, was traumatic for both of us.

The result of all this was that more than fifty years later I named a horse Sloan, after the porter on the train I was always taking to one boarding school or another. I loved Sloan the porter because he showed me more affection than my father. And I learned very early that the love of animals never wavers, while the love of people can’t always be trusted. As a result, the love of animals has been one of the constants of my life.

My resentment made me a rebellious kid, and I had a way of being a handful at the four boarding schools I attended. Once, when I was twelve or thirteen, I took a BB gun and shot all the lights out in the tunnel of the country club at Bel-Air and generally embarrassed my father by being a smart-ass. The country club incident made him close his fists and go after me—again—but a couple of other men held him back.

My best friend in these difficult years, and for the rest of his life, was Bill Storke. Bill’s background was exotic—his mother was the mistress of a very rich man, and there was always the possibility that he was the illegitimate product of that liaison. Bill was six or seven years older than I was and dated my sister for a while. It wasn’t long before he became part of our family. My dad got him a page job at NBC, and for the rest of his life Bill served as a sort of unofficial older brother for me.

Shortly after the incident with the BB gun, Bill and I got loaded, and I got sick all over the floor and the rug, which got my father royally pissed off. “I can’t depend on you,” he told me and went on to call me a lot of names.

As a result of the way I was raised, I never spanked my own kids, and I’m glad I didn’t.

One of the schools I attended was the legendary Black Foxe Military Academy, which had been started by a washed-up silent movie actor named Earl Foxe. Whatever Black Foxe might have done for other kids didn’t work for me. I got kicked out and then proceeded to get kicked out of yet another place. I especially hated Black Foxe, hated the regimentation, the way older kids were given ranks like “captain” and used to control the younger kids. I loved the swimming and the athletics, but I simply wasn’t cut out for that kind of environment. Black Foxe operated by fear, and that has never worked with me. As far as I was concerned, I was being filed away yet again. More than anything, I just wanted to be riding my horse.

Throughout this period, my mother, who was a little woman, tried to take my side. For that matter, throughout her entire life she took my side. In a few years, she would give me money for gas so I could go to acting tryouts, or she would even drive me there. But she had her hands full with my father because his house and his children were run his way. He ruled. If I came to her with something that was outside her range of authority, she would say, “I can’t do that. You’ll have to talk to your father.”

If the first eighteen years of my life can be reduced to a single sentence, it would be this: I wanted out of my father’s life.

In a sense, I was a teenage rebel. Don’t get me wrong—I wasn’t living in a Dickens novel. I think it’s interesting that my father was noticeably easier on my sister, Mary Lou, than he was on me. She was a girl, and as his son, I not only had to succeed—I had to succeed on his terms.

That said, I remain in awe of his business acumen. My father was a singular man in most respects, but like everybody else, he took a bath in the Depression. Until then, the auto business had been on fire, and he’d been very successful. My mother had a very bad asthmatic condition, so they were going to leave Michigan and move to Arizona, but then they fell in love with California.

He bought a lot in Bel-Air, overlooking the Bel-Air Country Club, which was an example of his innate investment savvy—Bel-Air was nothing at that point. From there, he bought a lot at Rancho Santa Fe, in the desert, and more lots in Bel-Air. He’d buy a lot, build a house on it, then sell it and make a lot of money. And then he got into the aviation business. Along comes World War II, and once again he’s—you should pardon the expression—flying high. And that time he held on to his money.

It’s clear to me now that my father had a depression mentality before the Depression, and the result was that he lived his entire life on the short side—always a room, never a suite. He was the sort of rich man who never wanted people to think he had any money. He’d want us to wear clothes after they’d begun to wear out. Yes, he gave me a horse, and I had to take very good care of the horse—fair enough. But if the horse needed something, I had to go through hell to get it.

Years later we’d be in Europe and he’d look at the bill and begin bitching about how much things were costing. “Why are we here?” he would say. “I know they’re charging us more than they’re charging other people!”

After I was in the movie business, I went to Hong Kong to shoot a picture, and he came with me. By that time he was watching my expenses the same way he watched his own. He kept a log of what I spent on food or at the dentist. It kept him occupied, which was fine with me. We took a rickshaw together, and he gave the driver some money. The rickshaw man gave him his change in yens, which neither of us could compute. My father began obsessing over whether or not he had been shortchanged. I finally had to tell him, “Dad, forget about the money! Look around, notice where you are. Let it be.”

Apropos of this mind-set, I went to school with Sydney Chaplin, Charlie’s son. Sydney told me how his dad once accidentally gave a cab driver a $100 bill when he’d meant to give him a $10 bill. Charlie was miserable for three days after that. He wanted to find the cab and get the driver to give him back his change. Both Chaplin and my father had been truly poor, and it deformed them emotionally. It’s impossible to relax, or even have much happiness, with that point of view.

Although I wouldn’t have wanted a marriage like my parents had, they seemed happy. I never knew my father to be a philanderer, even though he spent a lot of years as a traveling salesman. He certainly had his secrets, but they wouldn’t come out until after he died.

The end result of my childhood and my relationship with my father was that I consciously went 180 degrees in the opposite direction. My father would take me to movies on Thursday nights, but he wasn’t a movie fan the same way I was. The arts didn’t really interest him—he was a bricks-and-mortar man. Bill Storke once told me something that’s stuck with me: “Your father never gambled on you,” he said, and I think he was right. But then, my father never gambled. For him, money was strictly for security, and there was no such thing as enough security. For me, money has always been for sheltering the people I love, and for pleasure. My father was only interested in investments that had a guaranteed return, and I suspect he saw his son as an investment that showed no signs of paying off.