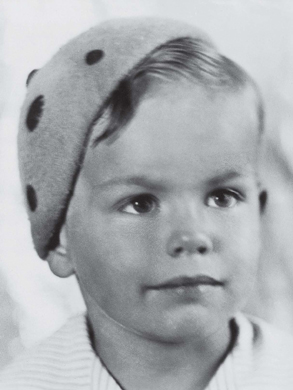

The beret indicates a certain theatrical bent, n’est-ce pas? (COURTESY OF THE AUTHOR)

Because my father had money and belonged to the Bel-Air Country Club, I had entrée to a life most people couldn’t dream of, and I never took it for granted. One fortunate by-product of the private schools I was attending was that I was cheek by jowl with a lot of kids with famous parents.

The first movie star I met was Norma Shearer. I was eight years old at the time and going to school with Irving Thalberg Jr. His father, the longtime production chief at Metro-Goldwyn-Mayer, devoted a large part of his creative life to making Norma a star, and he succeeded splendidly. Unfortunately, Thalberg had died suddenly in 1936, and his wife’s career had begun to slowly deflate.

Just like kids everywhere else, Hollywood kids had playdates at each other’s houses, and one day I went to the Thalberg house in Santa Monica, where Irving Sr. had died eighteen months before.

Norma was in bed, where, I was given to understand, she spent quite a bit of time so that on those occasions when she worked or went out in public she would look as rested as possible. She was making Marie Antoinette at the time, and to see her in the flesh was overwhelming. She very kindly autographed a picture for me, which I still have: “To Cadet Wagner, with my very best wishes. Norma Shearer.”

Years later I would be with her and Martin Arrouge, her second husband, at Sun Valley. No matter who the nominal hostess was, Norma was always the queen, and no matter what time the party was to begin, Norma was always late, because she would sit for hours—hours!—to do her makeup, then make the grand entrance. She was always and forever the star. She had to be that way, really, because she became a star by force of will—hers and Thalberg’s. Better-looking on the screen than in life, Norma Shearer was certainly not a beauty on the level of Paulette Goddard, who didn’t need makeup, didn’t need anything. Paulette could simply toss her hair and walk out the front door, and strong men grew weak in the knees.

Norma found the perfect husband in Martin. He was a lovely man, a really fine athlete—Martin was a superb skier—and totally devoted to her. In the circles they moved in, there were always backbiting comments when a woman married a younger man—“the stud ski instructor,” that sort of thing. But Martin, who was twelve years younger than Norma and was indeed a ski instructor, never acknowledged any of that and was a thorough gentleman all his life. He had a superficial facial resemblance to Irving Thalberg, but Thalberg had a rheumatic heart and was a thin, nonathletic kind of man—intellectually vital, but physically weak. Martin was just the opposite—strong and virile, with a high energy level. Coming after years of being married to Thalberg and having to worry about his health, Martin must have been a delicious change for Norma.

Another classmate was Peter Potter, Fred Astaire’s stepson. Peter and I were both at the Hollywood Military Academy, which was located on the corner of San Vicente and Bristol. Peter and I would have playdates at his house, and Fred would pick me up from the school in a cream-colored convertible—a Packard, I think. Even though I was just a small kid, Fred was always very kind to me. It’s one of those strange twists of fate that thirty years later he’d be playing my father on It Takes a Thief.

When I was eight years old, there was a preview of a Paramount picture called The Biscuit Eater at the Village Theater in Westwood. It was about a white kid and a black kid who take the runt of a litter and try to turn him into a champion bird dog—a sweet, lovely little picture that, because of my passion for dogs, moved me terribly.

At the end of the movie I was crying, and when I came out of the Village Theater still sniffling, there was the dog from the movie! The trainer had brought him to the screening for some publicity, and I was so thrilled to see the dog that I ran right up to him and threw my arms around him. Luckily, he was a well-trained dog and didn’t bite me or shy away. Well, the photographers who were there were just delighted—a picture of a sobbing child with a dog is guaranteed to get good placement in any newspaper at any time.

As the photographers were shooting and the flashbulbs were going off all around me, I distinctly remember thinking, Gee, this is pretty good! I was the focus of a circle of light, the center of everybody’s attention, and I liked it. It was one of the key moments of my life.

The years of my early adolescence were tough for me. I was something of a jock, excelling in baseball, swimming, and tennis, and I was also good on a horse. Academics were another thing entirely. It wasn’t that I didn’t have the aptitude, although I’m sure some of my teachers would have insisted otherwise. It was that I was bored and rebellious and didn’t try to conceal it.

In retrospect, my parents had a lot of trouble with me. I was always with tutors; one time, at Harvard Military School, I got caught with a girl, and there was a point when I went from being kicked out of Black Foxe to getting kicked out of Harvard to being at Cal Prep—which I liked—and then it was St. Monica’s and living at home.

These years were lightened only by my increasing addiction to the movies. When I was at Black Foxe, RKO came to the campus to shoot some scenes for Best Foot Forward. Our company of cadets marched by, and the Hollywood crew photographed us. I was fascinated by the trucks, the crew, the way the shoot and the extras and all the paraphernalia of moviemaking were organized.

Everything seemed to contribute to my passion for the movies. One of the kids I went to school with was the son of Edgar Rice Burroughs, whose ranch, dubbed Tarzana, was later developed into an entire town. Mr. Burroughs would invite a bunch of the kids out to his ranch, and believe me, in the days before freeways Tarzana was a trek. Of course, we were all nuts about Tarzan, so we knew who Edgar Rice Burroughs was. It wasn’t just another trip to a parent’s house.

It turned out that Burroughs had wired his gardens for sound, and there was a profusion of jungle noises coming from the trees. We’d hear monkeys gibbering and ask “Who’s that?” and Mr. Burroughs would say, “That’s Cheetah.” And then we would hear Tarzan’s yell, and he would nod and say, “That’s Tarzan.” We’d all stare wide-eyed at the vegetation waiting for Johnny Weissmuller to show up. Burroughs was a gracious, wonderful gentleman, and we all loved to visit him.

As momentous as my commitment to the world of the movies was my discovery of sex, which happened just around the time I saw Astaire, Gable, Scott, and Grant at the Bel-Air Country Club. I was about twelve and a half, in junior high at Emerson. This wonderful, sweet girl sent me a note: “I would like to make love to you.” She didn’t have to ask twice. I folded up the note and went right over to her desk and made a date.

Afterward, I thought I had discovered the greatest thing on earth. Certainly, it was a lot better than masturbation. Someone must have broken the girl in awfully early, because she wasn’t a virgin. She told her friends about me, because I soon had easy access to some of the other girls as well.

Some of my first official dates were with Alan Ladd’s daughter Carol, Harold Lloyd’s daughter Gloria, and Joan Bennett’s daughter Melinda. It was around this same time that I went to a pool party and met Roddy McDowall, who was already part of Elizabeth Taylor’s group of teenagers. Roddy was then as he always was—immensely kind and decent, with a caring, empathetic quality that made him one of the most beloved members of the Hollywood community. Roddy and Elizabeth would be the most intimate of friends for the rest of his life, but then one of Roddy’s great gifts was that all of his friends felt that they were on the most intimate of levels with him.

The proximity of the movie business to my life only increased my hunger. One day I was hitchhiking on Sunset Boulevard when it started to rain. A car stopped for me, I hopped in, and when I turned to thank the driver my mouth stopped working. He looked just like Errol Flynn. Dear God, it was Errol Flynn, and I had just seen Objective, Burma!

I gulped and said, “You’re Errol Flynn!”

“Yes, I am,” he said, and the nearness of Errol Flynn was so staggering that that perfectly innocuous exchange is all I can remember of the entire ride.

Another time Alan Ladd was shooting some scenes on an estate in Bel-Air, and I snuck onto the set to watch. He was standing behind some bushes waiting to make an entrance, and I got a chance to watch him work. He was a powerful screen actor—that great voice, that blond hair, that sense of stillness. And yes, he was small, but not that small—about five-foot-six, with a terrific swimmer’s body. The problem was that his image was not that of a guy who was five-six. On screen, he was six-three, so when people saw him they were always surprised, which made him insecure.

Years later I did a magazine layout with Alan at his ranch in Hidden Valley and got to know him. Alan Ladd was an extremely kind man, and a good horseman who knew how to handle an animal. Unfortunately, he had a complicated series of disappointments involving his marriage to Sue Carol, smoked a lot of cigarettes, and got hooked on booze, which greatly affected his looks and his career choices. At the end, his family was watching him closely, but not closely enough.

Throughout these years I never had any career goal other than acting, and I see no need to apologize for it. I thought then and I think now that making people smile and taking them out of their problems for an hour or two is a wonderful way to spend a life. I know that because that’s what the movies did for me. When I would come home from an afternoon at the movies, I would go to my bedroom and act out the best scenes from whatever I’d seen that day, and my problems with my father were forgotten. That era provided a profusion of wonderful actors and actresses to admire—and not always the ones remembered by posterity. Take Joel McCrea, for instance, a real cowboy and a good actor who could excel in westerns like Union Pacific or The Virginian, but who was also wonderful in comedies like The Palm Beach Story for Preston Sturges—and comedy is the hardest thing an actor can do.

I was always trying to turn my passion from the theoretical into the practical. When I attended the Hollywood Military Academy, we did a production of The Courtship of Miles Standish, and I played a female character—Priscilla Alden! I also played Tiny Tim in a production of The Christmas Carol and kept up with the amateur theatricals, thankfully in male parts. I was coming up in the world!

One of my close friends in school was named Noel Clarabitt. Helena, his mother, had a little tearoom, and I would work for her, polishing the antiques and crystal and busing the tables. I would be over at their house a great deal, and she became a big influence; she was Russian, and they drank wine and played classical music, which was a different environment than I was used to.

Southern California was paradise in this period. For one thing, there weren’t that many people, which meant there weren’t that many cars, which meant there was no smog at all. The air was so clear that when the smudge pots were lit in preparation for a freeze in the orange groves, you could smell them all over town. There was a superb transit system in the Red Line, which went from downtown L.A. all the way to the ocean. One of the main routes was down San Vicente Boulevard; what’s now the large grassy divider in the middle of the road was the trolley track. In more congested areas, the Red Line took back routes, but when the cars got to Hollywood, there would still be stops at Highland and La Brea. People would take the Red Line all the way to the beach, where the car was turned around on a large turntable before it headed back downtown.

You could stand on a mountaintop in Malibu or Santa Monica and see all the way to Catalina. Literally. On top of Sepulveda, you could look out into the San Fernando Valley and see nothing but chicken and avocado ranches. The primary industries were movies and aircraft, which had boomed during the war.

The old Los Angeles I grew up with is all gone now, except for a couple of places that are entirely commercial. If you want, you can go to the Huntington or to Olvera Street, but those are museums, each in its own way. The Red Line disappeared because the rubber and fuel companies wanted the trolley cars out so they could make more money. But that’s the way of the world; when I was at Cal Prep, I used to fish for steelhead in the Ventura River up near Ojai, and now the Ventura River doesn’t even run there anymore.

I finally began to get some serious traction when I began caddying at the Bel-Air Country Club. One of the admirable by-products of my father’s value system was a belief in hard work. He always wanted me to be earning my keep, and since it got me out of the house, I was all for it.

Under ordinary circumstances, there would have been a lot of competition for those caddy jobs at Bel-Air and I would have gotten shut out because I was too young. But after Pearl Harbor, all the older caddies went to war or got more lucrative jobs in the aircraft factories as they ramped up production, so I was able to nab a spot I wouldn’t have gotten for at least a couple of more years.

The Bel-Air Country Club gave me a matchless opportunity to meet and watch people, but it also gave me a primer in some of the less palatable personalities in the business. Most of the extremely right-wing members of the Motion Picture Alliance frequented the Bel-Air. Adolphe Menjou was often there, prissy and slightly effete, the sort of man who never read a novel, only the Wall Street Journal. When Lew Ayres claimed conscientious objector status during World War II, the right-wingers at Bel-Air thought he was a coward and ostracized him. Lew was a strong man, a good man, and went his own way, eventually serving with distinction as a medic, which is more than the people who felt entitled to condemn him ever did.

If you caddied the full loop at Bel-Air, eighteen holes, you’d get paid two or three dollars. All the players tipped about the same—a dollar or so. Clark Gable always gave you a little extra, but it wasn’t a tipping society. In any case, I have a lingering feeling that my passion for show business got in the way of what should have been my passion for caddying.

Once, I stole a script out of Robert Sterling’s golf bag and took it to a friend of mine named Flo Allen, who later became an agent. We read it over and tried to figure out how it should be acted. There was one scene in the script we worked on particularly hard.

It began: “Want a cup of coffee?”

“Sure.”

“Cream and sugar?” And so forth, with lots of byplay with props. To this day, whenever I call Flo, I open by saying, “Want a cup of coffee?” Considering the level of effort I was putting into trying to learn how to act versus the level of effort I was putting into caddying, it was a miracle nobody complained. It was a bigger miracle that I didn’t get fired.

The fact that I was working at Bel-Air didn’t make my dad any more kindly disposed toward me. Things got so bad at home that when I was fourteen or fifteen I seriously considered joining the merchant marine. Bill Storke had joined up, and that gave me the same idea. World War II was still on, and they needed men, but the cutoff age was sixteen. No dice.

Right after the war, in 1945 and ’46, I began spending a lot of time on Catalina, and I started hanging around John Ford’s crew of reprobates, who all docked their boats at Avalon. Ward Bond was always there, and Robert Walker—he would court and later marry Ford’s daughter, Barbara—as well as John Wayne of course, and Paul Fix.

Ford’s group, as well as other people who had boats, began a series of softball games. I never pitched but could play anywhere in the infield or outfield; first base was an especially good position for me. All of these men had been athletes—“Duke” Wayne and Ward Bond had been teammates on the USC football team—and they knew how to play baseball. They were good athletes, and good athletes have a certain native proficiency at any sport, but what I found surprising was that they were also extremely competitive; it might have been only a pickup game of softball, but they played hard and they played to win. John Ford was around but didn’t play much, which, now that I think of it, was odd because he had been a jock when he was a kid.

It was while I was spending a lot of time around Catalina that I met a sailing man named J. Stanley Anderson. His daughter had been hurt in an accident, and I used to cheer her up by doing imitations of famous actors. Anderson had connections in the movie industry and, in due time, would lend me some of those connections.

On those rare occasions when I wasn’t thinking about acting, I discovered that you can learn a lot about a man’s nature by observing how he plays sports. Bing Crosby, for instance, was a very fine golfer, but beyond that, he was a smart golfer. He knew the game, had a great swing, and was very consistent. He worked a course the same way he worked his career: he made it look easy, but he was thinking all the time, and he had good instincts. Fred Astaire was a good golfer because he had superb timing and rhythm, which is the essence of sport as well as of dance.

By comparison to today, golf was in its infancy. There wasn’t a profusion of courses, and those courses that did exist weren’t all that crowded. It was a more leisurely sport and a more casual time, so it was easy to strike up a conversation with the players if they were so inclined—or even if they weren’t. Randy Scott said he could be right in the middle of a back swing when I would interrupt with some question about the movie business.

Clark Gable was charming, engaging, very unpretentious, the sort of person you felt comfortable talking to about almost anything. One day I told him I wanted to be in pictures. He liked the way I looked, and oddly, he liked the way I caddied, so he took me over to MGM to meet Billy Grady, the head of talent. Grady told me I needed to go to New York, go on the stage, and get some seasoning. “You need help,” he said. “You need an edge.” MGM and the other studios covered the stage, and they’d watch my progress. “Read a lot of books,” he said. “Read them aloud in the backyard, to roughen and lower your voice.”

I realize now that this was his Acting 101 speech to anyone who came to his office, but at the time it was a very important conversation. I also went to see Lillian Burns Sidney, who was the drama coach at MGM and who sang my praises to her class later on.

And then Stan Anderson, whose daughter I had entertained with imitations, sent me to see Solly Baiano at Warner’s. I did my impersonations of Cagney, Bogart, and the rest for Solly, and all he said was, “Well, that’s all very well, but we’ve already got Cagney, and we’ve already got Bogart. What about doing you?”

That rocked me back. I thought about it and sensibly pointed out that “I can’t do me. I don’t know who me is.”

In spite of my unformed state, Solly liked me and was going to put me into a movie. But fate intervened when the studio was closed down by a strike, and I had to go back to St. Monica’s, where I was going to high school. After that, I tried Paramount, where a lovely woman named Charlotte Cleary treated me with great kindness and enthusiasm. I auditioned in what they called “the fishbowl.” The fishbowl looked like a projection room with a small stage area in front of the screen. At the back of the room was a glass window, and you couldn’t see through it to find out who was watching you. It was like being in a police lineup, and it was unnerving. When the scene was over, they’d talk to you through a PA system. You couldn’t see who you were playing to, and it didn’t work for me at all.

My father’s response to all this unvarying: “What the hell are you doing? What makes you think you can act?”

“I want to try it.”

“Well, you’re not going to try it. Go work in a steel mill this summer and learn about alloys.”

This exchange, with minor variations, went on for years. For a while I was out there with a briefcase, fronting “Robert J. Wagner and Son.” I didn’t know much, but I knew I didn’t want to be the back half of “Robert J. Wagner and Son.”

Another dead-end job was selling cars, although one day I got in to see Minna Wallis under the pretext of selling her a Buick. Minna Wallis was Hal Wallis’s sister and a well-regarded agent. Years earlier, she’d had an affair with Clark Gable and gave him a considerable career boost with her advice. I was a lot more interested in impressing her with the sleek beauty of Robert Wagner than I was in impressing her with the sleek beauty of a Buick. She was very encouraging, and years later I gave her an autographed picture on which I wrote, “Any time you want to buy a Buick, let me know.”

Finally, my father capitulated slightly. My mother had been working relentlessly on him, and it had become increasingly obvious that I wasn’t going to college. I was offered scholarships to USC and Pomona, for diving and swimming, but I don’t think I could have made all-state. I was ranked about thirty-second in the state in tennis, which wasn’t bad, but I wasn’t really good enough to be a professional.

There were really only two paths: my father’s way into business, or my way into show business. I remained adamant. Finally, my mother threw herself into the fray. She insisted that they had to let me at least try my way, so my father and I came to an agreement. When I graduated from St. Monica’s, he gave me a convertible and $200 a month for a year. If I couldn’t get into the movies in a year, on that money, I had to go into business with him. It wasn’t a great deal, but it was a better deal than anything he’d offered me up till then. We shook on it.

I had met William Wellman on the golf course at Bel-Air. He was a friend of my dad’s and a very fine, successful director who had given a lot of people their start, including Gary Cooper in Wings, Wellman’s great World War I epic that won the first Oscar for “Best Picture” in 1927. My father swallowed hard, went to Wellman, and said, “I’ve got this kid who wants to be in the movies. Can you do anything?” Wellman probably heard this same line two or three times a week, but he gave me a small part in a good film he was making at MGM: The Happy Years. You never saw me—I was behind a catcher’s mask, and you would have had to have been my mother to recognize me—but I was in a movie. Needless to say, I was over the moon.

Wellman had the reputation of being a wildly enthusiastic but temperamental taskmaster, but he was great to me; he even put me in another scene I wasn’t supposed to be in. It was my first movie, but I didn’t have a sense of how movies worked overall. I earned precisely $37.50 on The Happy Years, which I’m sure didn’t make my father feel any better about my choice of a career. Far more important than the money was the fact that I was now entitled to membership in the Screen Actors Guild—not bad for eighteen years old!

With an appearance in a major studio film behind me, I went to Phil Kellogg, a well-regarded agent about town. Kellogg was with Berg-Allenberg, and he was Bill Wellman’s agent. With the bravado of youth, I asked him if he would handle me. I was really just grasping at straws, and Kellogg responded by giving me a talk about how difficult the business was, how many kids there were like me, and so forth. In a very nice way, he was trying to discourage me. After half an hour, he suddenly stopped, and I went away without an agent. But I’ve always been a positive, basically optimistic person, and I had a bumptious self-confidence—you couldn’t dissuade me. I just figured that if Kellogg didn’t want to handle me, someone else would.

Fully forty years later, I was having a talk with Kellogg and thanked him for taking so much time with a green kid. And he told me that he’d actually been told to talk me out of being in the movies, but my enthusiasm got the best of him, and after a while he had to stop.

“Who told you to talk me out of it?” I asked, although I already knew the answer.

“Your father and Bill Wellman,” he said.

Well, at least my father was consistent. For the year that he financed me, I worked as an extra and did everything there was to do so long as it was on a movie lot. I was always trying to get meetings with a producer, and if I was working in a crowd scene, I’d try to get placed in the front. For a time I was going out with Gloria Swanson’s daughter Michelle. Gloria was preparing Sunset Boulevard, and she listened as Michelle and I told her how much we wanted to be actors. Gloria gave us a copy of the script of Sunset Boulevard, and Michelle and I worked up a scene. Then Gloria had her friend Chuck Walters, a good director at MGM, come and watch us do the scene, then give us notes.

All my scrounging and determination got me a lot of one-day jobs, and one thing led to another, as it usually does. One night I was at a club called the Beverly Hills Gourmet, where a songwriter named Lou Spence was playing the piano. I was up there by the piano singing some comedy lyrics that Spence had written to the tune of “Tea for Two” when a well-known agent named Henry Willson came in with his secretary. He sent a card over to the piano with a note that said if I was interested in being in pictures, I should come and see him. Well, I knew who Henry Willson was; everybody knew who Henry Willson was—a very important man at Charles Feldman’s Famous Artists Agency. I also knew he was gay, although he wasn’t mincy.

Famous Artists had strong connections at Fox, and that’s where he sent me over to test. Years later, after I made it, a reporter asked Willson what he had seen in me. God knows, I was curious about that myself, because as Natalie Wood would say about me, “He was a star before he was an actor.”

Willson replied that what had impressed him was “the changing expressions on his face. I watched his face mirror every thought and word—that, together with his looks and bright, clean-cut personality. I saw a sincerity and relaxed quality that would come right across the screen. Given the opportunity, I was sure he couldn’t miss.”

During the time that he represented me, Willson never made a pass, although if I had put myself out there, he would have been on me in a second. He always treated me professionally, but there’s no question that Henry was sexually acquisitive. Once, he hitched a ride with me to the Racquet Club in Palm Springs. I was going there because there was a girl there I wanted to see, but Henry picked up a guy at the club using me as bait, which pissed me off royally.

Years later Mike Connors and I counted up the number of straight clients Henry had at that time. We were able to come up with three: the two of us and Rory Calhoun. It was really another time. In those days most gay men were in the background. To get together, they’d rent houses or go on beach parties, because there weren’t that many gay bars around. Now there’s a book for every town telling gays where to go, and gays are in the foreground.

Henry was a very tricky guy, and I don’t think he was an admirable person. He pulled a particularly horrible stunt on Rory Calhoun, when he leaked Rory’s juvenile record of grand theft auto to Confidential magazine in order to get them to sit on a story about Rock Hudson being gay. He gave up one client—Rory—to save a more important client—Rock. Years later, after Natalie Wood and I had remarried, Henry called and wanted us to pick up the mortgage on his house. He’d blown all his money, among other things, and he couched his request for help in the sinister overtones of a threat. He wouldn’t want anything derogatory about us to come out, and so forth. We ignored him.

Just before I tested at Fox, I heard about a script at MGM that Stewart Stern had written. It was called Teresa, and it was about a young American soldier and his Italian war bride. The director was Fred Zinnemann, not yet the major figure who would make High Noon and From Here to Eternity, but clearly a rising star, one who already had the reputation of being a wonderful director. I got an interview, and Stewart and Fred both were very encouraging, even though I was painfully inexperienced. Stewart very kindly worked with me for about a week, taking me through the scene moment by moment. After a week, I went to MGM and made the test, which Fred directed himself.

MGM took one look at my test and gave the part to John Erickson. I don’t blame them; I was just too green. A little while later I received a wonderful letter from Zinnemann, telling me that although I wasn’t right for this particular part, I was a genuine talent and I had a wonderful career ahead of me. In the sixty years since, I have never been turned down with more class. It was completely misleading in that I thought Zinnemann’s graciousness and style were a nominal part of the movie business. It took me a couple of years to figure out that Zinnemann was one of the few people of that era who would show such kindness to a young actor. It was Fred Zinnemann who taught me that the mark of a gentleman is how he treats people he doesn’t have to be nice to.

Fade-out.

Fade-in.

Forty years later, Jill St. John and I were in London, and Fred Zinnemann was getting an award at the National Film Theater. We went over for the evening, and not only did he remember my test, but he remembered the letter! Fred Zinnemann was a great director, of course, but what is more important is that he was also a great man.

It was around the time I was testing for Teresa that I met Albert “Cubby” Broccoli, who was an agent at Charles Feldman’s Famous Artists before he became a producer and achieved deserved fame and fortune with the James Bond films. Cubby came up through the trenches. Before he was an agent and producer, he sold jewelry, he sold Christmas trees, he worked in a studio mailroom, and he was an assistant director at Fox.

To know Cubby was to be his friend, and it was Cubby who took me around to some of the studios. I was with Cubby when we were both thrown off the MGM lot. It seemed that Charlie Feldman had begun an affair with an actress in whom a certain MGM executive had a deep and sustaining personal interest, so Feldman and everybody who worked with him were deemed persona non grata.

Despite that faux pas, Cubby and I hit it off, and for years I was invited to his house for Christmas and New Year’s. He and his wife opened their arms to me, and when Cubby’s health began to fail, I made sure to return the favor. I visited him regularly, as a great many people did. When he died, I gave the eulogy at his funeral—a small favor for a man who had done so much for me—and many others.

After testing for Teresa, I went over to Fox. I had known the Zanuck kids—Susan, Richard, and Darrylin—socially, not that that would cut me any slack when it came to business. I made my test, and Darryl Zanuck looked at it the next night—Darryl always worked a late day. He ran the footage and said, “I don’t think so. Too inexperienced.”

But Helena Sorrell, the studio’s drama coach, asked him to run the test one more time. “Look at his smile,” she said. “I think I can do something with that smile.”

So Darryl ran the test again, sighed, and said, “Okay, Helena, if you say so. We’ll give him six months.” I signed a standard studio contract that started at $75 a week. I was eighteen years old, and since I was still a minor, part of my salary was withheld under the Coogan law. There were options—all on the studio’s side—every six months, with a slight salary boost with each option that was picked up. My $75 a week would become $125 a week, for instance. If you were picked up for an entire year, you were guaranteed forty weeks of salary out of fifty-two, but the studio could put you on furlough anytime it wanted, during which time you weren’t paid.

During the forty weeks you were being paid, you could be making movies, of course, but the studio could basically tell you to do anything else it wanted as well—publicity tours, testing with other actors, whatever the studio chose. Since we were being paid, nobody much minded.

The fact that I could make $75 a week caddying at Bel-Air, or selling cars, or working for my father didn’t bother me at all. Far more important than the money was the fact that the contract got me inside a movie studio. The contract didn’t arrive quite within the year my father had given me, but it was close enough so that I didn’t have to go back to being the back half of “Robert J. Wagner and Son,” which was all I cared about.

Twelve years later, Fox was paying me $5,000 a week.