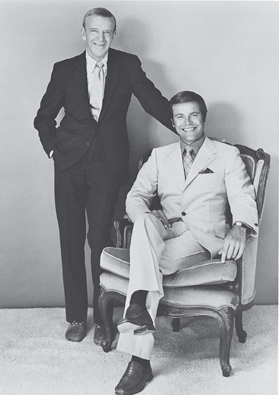

With Fred Astaire, the greatest dancer of them all. (COURTESY OF UNIVERSAL STUDIOS LICENSING LLP)

Taken together, The Pink Panther and Harper were the beginning of my comeback. In retrospect, I can see that I was never entirely out of options. I may not have been doing the things I would have wanted to do in an ideal world, and I may not have been making the money I wanted to make. But from this time on, I was always going forward, always had something on the burner. Marion was very supportive, and my friends were always there for me.

Time. The key factor is time. Things can change in a minute. A lot of young actors have come to me over the years and talked about how hard it is to make enough money for their families. They can be working, then six or eight months go by with nothing at all, and that can be terrifying. They worry about money, about having enough for their children’s needs.

I tell them that the prime factors are time, listening, and the refusal to do anything other than keep going. What’s Micawber’s line in David Copperfield? “Something will turn up.” In my experience, something always does turn up, but you have to be alert to it when it does.

Find smart people and listen to them. When Lew Wasserman sat me down in 1966 and told me how good I could be on TV, I didn’t just say, “Fuck television, I only make movies!” Lew Wasserman was a very bright man, with a track record. You ignored Lew Wasserman at your peril. Ditto John Foreman. You have to listen to smart people who take the time to tell you things.

This is how I came to television: after Harper, my agents made a three-picture deal for me at MCA/Universal. Lew Wasserman called and said he wanted me to do one of the shows on The Name of the Game, an NBC show with rotating stars.

“I don’t want to do television, Lew,” I said. “I want to stay in the movies.” At that time, there was still something of a stigma attached to TV, and I talked about that. But Lew was Lew, and we kept talking. Other people were slotted into The Name of the Game.

Finally, Lew shifted his tactics and said, “Look, we have a great property that’s been written just for you, and you would be wonderful in it. I guarantee you that if you make the pilot and we can’t sell it as a series, we’ll make a movie out of it.”

He explained the show to me. I was to play Alexander Mundy, a cat burglar and gentleman thief who has gotten caught. While he’s in prison, a government spy agency offers to spring him if he’ll work for them, with the possibility of total freedom being dangled as the carrot to keep him in line.

I’ve heard much worse premises for TV shows, and Lew’s suggestion sounded like a good compromise to me. I checked with David Niven, who had gone into TV during a fallow period in his career and made a fortune as a partner with Dick Powell and Charles Boyer in Four Star Productions. David strongly suggested that I give it a whirl. Lew had given me the full-court press, but with David’s recommendation, it was game, set, match. I made the move into television, and it proved to be wise, as well as lucrative.

I trusted Lew’s and David’s judgment, but there was one remaining problem—I was still feeling unsure of myself. I hadn’t really addressed the stage fright I had on The Pink Panther; if it came back, I knew it would be even more crippling than it had been before.

I went to Gadge Kazan and told him what had happened. Gadge had forgotten more about actors than most directors will ever know, and he suggested I see a therapist, which did indeed help. The more you find out about yourself, the more you can cope with the things life throws at you. And what I found out was what I had long suspected: losing Natalie was the root cause of my insecurity as a professional.

After I agreed to do It Takes a Thief, I went to Cary Grant, who had played a similar part in Hitchcock’s To Catch a Thief.

“Do you have any ideas?” I asked him.

Cary looked at me and said, “Yes, I do. Bring you to the part.”

It was like a door opening. In the movies, I had always been concerned about playing the character. It hadn’t really occurred to me to use my own personality because, like a lot of actors, I wasn’t all that sure about my own personality. “Bring you to the part” sounded risky—what if they didn’t like me? And if they don’t like you, what’s your fallback position? But Cary was a sharp man and had done rather well by bringing aspects of himself to his parts. I decided to give it a try.

Universal was at an interesting stage in its development. About two-thirds of its production was slotted directly for television. Because of its extremely heavy volume, the studio had basically reinstituted the contract system that had died out in the 1950s. Universal had three or four character heavies under contract, a half-dozen leading men, and boxcars of male and female ingenues. It wasn’t surprising—Lew Wasserman was an enormous admirer of Louis B. Mayer and the way he had run MGM.

But Mayer had never offered guided tours of his studio to the public, and Lew did. Universal even built sets that were ostensibly part of the backstage apparatus of the studio but were actually just window dressing for the tours; at one point there was a set that tour guides would tell people was “Robert Wagner’s dressing room.” The folks would come in, walk around, and feel like they’d been in my backyard. In reality, I was never there. No one was, except the tourists. All the people working at Universal were expected to play along and be cordial whenever the trams came by, even if they were an irritating imposition.

One day on the lot the trams came by, and the guide said, “Ladies and gentlemen, there’s Neville Brand on the corner!” The people in the tram waved, and so did Neville Brand. And then the guide said, “And there’s famous dress designer Edith Head!” Edith took a big sheaf of sketches she was holding and shook them at the tourists like the sketches were signal flags!

The first thing I did at Universal was a TV movie, a lighthearted thriller called How I Spent My Summer Vacation, which had a very good cast: Walter Pidgeon, Lola Albright, Peter Lawford, and a delightful actress named Jill St. John. It ran in January 1967, and we outrated the television premiere of the Sam Goldwyn production of Guys and Dolls. Lew was pleased, and I was pleased.

Then Lew slotted me into a theatrical, a movie about a golf pro called Banning. It was a pleasure for me because I love to golf, and I was again working with the delightful Miss St. John. It was a good picture, but golf movies have never set the box office on fire, probably because the pace of the game is too slow for drama, and Banning was no exception.

Finally, it was time to put It Takes a Thief into production. Eddie Dmytryk very kindly agreed to direct the pilot, and Lew was right—I did like TV, the pace, the constant flow. I’ve always been a man who likes action, and TV is made for that temperament. So we made the pilot, and ABC passed on it. I headed off to Brazil, where I directed a documentary about the bossa nova called And the World Goes On. Soon after I got there I got a telegram: It Takes a Thief was going on at midseason. I couldn’t believe it; what I didn’t know was that the studio had recut the show and added some scenes, and the new version had sold.

At this point, I figured I was in deep trouble. For one thing, midseason shows of that period could usually be characterized as lame, halt, or blind—sometimes all three. They were cannon fodder to be thrown on the air and to fill time until the shows the networks really cared about could come on in the fall. For another, the show had been diddled with, and because of that I felt less a part of it. I steeled myself for the firing squad.

It Takes a Thief went on the air on January 9, 1968, and from the first episode the show was a hit. As William Goldman wisely observed many years later, “Nobody knows anything.” The year 1968 was, of course, the height of a very crazy time in the world, and I think the show served as a sort of retro escape valve. From Raffles on—which David Niven had played, if not quite as memorably as Ronald Colman—a gentleman thief involved with intrigue in exotic locations has never gone out of style.

Roland Kibbee had created the show and stayed on to run it with me. He was always called “Kibbee,” never “Roland,” but under any name he was a sensational writer and a good man to work with. Because of the show’s romantic nature, we had a lot of women guest-starring, which put more strain on the writers. Relationship scenes and love scenes have to be written from character, so it’s mandatory to have someone who can do more than write “Long shot: The building explodes.” Kibbee was perfect, and he helped make Alexander Mundy one of the best characters ever written for television.

I began alternating TV with movies, which became my modus operandi for the rest of my career and which I regard as the best of both worlds. This began a wonderful time of my life. Personally, Marion and I were solid, we had Katie, and I was professionally back on the upswing.

It was Kibbee’s idea to have a semiregular on the show who was related to me. I had a wonderful wardrobe man named Hughie McFarland who had also handled wardrobe for Fred Astaire and John Forsythe. Hughie had been around show business forever, had fallen into booze, but had then become a mainstay at Alcoholics Anonymous, where he helped hundreds of people get sober. Hughie was a wonderful man, and he and Fred were very close; in the years after Fred’s wife Phyllis died, Hughie had helped fill some of the lonely times—accompanying Fred to the track, going to the movies with him, that sort of thing.

When the subject of Alexander Mundy’s relative came up, it was Hughie who said, “Well, what about Fred?”

I hadn’t actually thought about Fred; for one thing, I regarded him as a friend, and I would have felt presumptuous asking him to be on any show that didn’t star Fred Astaire. I thought about it for a minute, then said, “Well, yeah, but can we get him?”

“Well, ask him.”

I was enthralled with the idea. My time with Zanuck had shown me that the secret to success in show business is to surround yourself with the best talent you can get and then give that talent room to flourish. I was never worried about being overshadowed; it was my show, and anything that made the show better would make me look better. And Fred Astaire never touched anything he didn’t improve.

I talked to Universal about getting Fred, and I told them that if he was agreeable, I didn’t want any problems—no haggling about money, billing, or anything. If Fred wanted to do the show, I said, give him whatever he wanted.

I had been close to the man I had seen on the eleventh fairway at Bel-Air for some time; we went to the track together and we played golf—nine brisk holes in the morning, and then off to work. When Katie was born, he gave her a gold bracelet with an inscription: I WILL ALWAYS LOVE YOU, KATIE. F.A.

You met the most interesting people through Fred—he introduced me to the great billiards player Willie Mosconi, for instance. I met Fred’s mother and sister, whom he absolutely adored. Although Fred’s parents were from Omaha, where he had been born, his mother radiated elegance and breeding. His sister Adele did too, but Adele had a bawdy sense of humor, with a vocabulary to match.

Actually, Adele swore like a drill instructor in the Marines. Needless to say, she was a much more outgoing personality than Fred. When she was around, he definitely retreated into the background, and he was fine with that, not that he had much choice—she took total command of the room.

But none of this had anything to do with working together. When I went over to his house to talk about the show, I told him, “This is a business deal. Do what you think best. I will love you no matter what.”

Fred and I talked, and he thought it sounded like fun. But when I went back to Universal with this wonderful news, they started bitching. This, I thought, was totally insane. I told them that this man was at the top of the alphabet as well as the top of show business; they could put his name at the top of the menu in the commissary: A for Astaire. You simply couldn’t treat Fred Astaire as if he were a day player.

Their objection wasn’t to his presence but to the money and the perks that a great star like Fred Astaire had earned many times over. It was at this point that I told Universal that I wasn’t Jack Webb and I had no interest in doing a glorified version of Dragnet: two-shots and close-ups, no action, no scenery, no guest stars, and everybody reading their lines off a teleprompter. One guy shuffled some papers and said they wished I was Jack Webb because, from the front office’s point of view, Jack Webb was the ideal filmmaker.

That was it. I drove off the lot and disappeared. We were in production, and they couldn’t find me. When they called the house, Marion told them I wasn’t there and she didn’t know when she would hear from me. I told my agent to tell them that when they had settled Mr. Astaire’s contract and apologized to him, I would be back. After four or five days, they settled.

As always in show business, wasting money is somehow expected, but wasting time drives people crazy, and that was what drove Universal to settle. The studio had stepped on a particular sore spot of mine: a lack of respect for people who have earned respect. I can’t and won’t accept that. So Fred’s contract was quickly settled. He got $25,000 a show, suites on location, and all the perks. And he more than met my expectations.

Once again, I had to get over the fact that I was working with a man I had worshiped since I was a child. But Fred made it easy. I had such great respect for him, and I was so proud to be working with him.

As an actor Fred was fully present, and as a man he was marvelous: substantial, honest, and totally straightforward. I never knew Fred to have a hidden agenda, and there wasn’t a duplicitous bone in his body. His ethic was basic: if he was going to do it, he wanted it to be the best it could be. He knew his work, and he loved his work. And yes, he loved to rehearse. When he was on the set, my crew was his crew; everyone deferred to him, as they should have. And to have him on the show was enormously exciting; it elevated the show, and it elevated me.

Glen Larson got the idea of how to introduce Fred on the show. We shot the introduction in Venice, where Fred and I were to run into each other. We had become estranged because Fred’s character, Alistair Mundy, was also a thief. I had gotten caught and let the side down. As far as Alistair was concerned, I had failed. We started production in Venice and then began moving south, toward Rome, writing and shooting as we went. I called the studio and said they should let us stay in Italy, that we could do a batch of shows and amortize the costs, and they said yes.

Now, of course, no network series could possibly do this because the costs of shooting in Europe are far too high; even then, it was highly unusual, especially for Universal, which preferred that everything be done at the studio.

We finally got to Rome, where we were shooting in a lovely villa. Fred and I had gone to lunch, and on the way back to the set the crew saw us coming in. One guy began clapping his hands rhythmically and called out “Fred!” The rhythm and the call were quickly picked up by the rest of the crew, and as “Fred!…Fred!…Fred!…” reverberated around the ballroom, Fred began to dance. He did incredible little combinations and twirls, kicked the piano, and danced around the ballroom to the clapping of the crew. It was pure dancing, for his own pleasure and the pleasure of the people he was working with. I just stood there and thought, Remember this.

What a time!

It was fascinating to act with Fred, but it was also fascinating to go to the track with him. Fred adored horses and the people who worked with them. Going to the track with Fred was like going to Rome with the pope. He knew everybody, from the owners to the stable boys, he could talk their language, and everybody liked him. Fred’s politics were Republican, but when it came to people he was a true democrat. He was comfortable with anybody, could talk to anybody. People cared about Fred because he cared about people.

He loved the track, I think, because of the commitment that’s necessary in racing. Everyone involved in racing, from the back of the track to the front, is totally devoted, and that was the way Fred worked. The job of the dancer is to train and rehearse a dance over and over again until the number is committed to muscle memory. At some point, the dancer reaches a point where he doesn’t have to think, he can just perform. It’s almost precisely the same thing a trainer does with his horse.

Acting with Fred was like that as well. We talked about scenes a lot—what we were going to do and what we were going for—and we rehearsed a lot. I found that Fred had innate intelligence, and he also had a great instinct for what worked for him and for the character he was playing. And then, when the cameras rolled, we threw all of that away; we weren’t talking about it as actors, we were playing it as the characters.

If you think about it, Fred was a very brave performer; he was always trying new things, and he never played it safe. It didn’t matter if it was utilizing innovative special effects for a dance number, recording a jazz album, or getting on a skateboard at the age of seventy-eight. Fred was always trying to do something more.

The blessing for me was that Fred’s knowledge of the business and what was needed to survive it helped me become better. When I would get down about the studio or my career, he would take me aside and tell me, “Don’t let them get on top of you. Don’t ever get negative. There are a lot of bumps in the road; you’ve got to keep your chin up. The most important thing is to keep going.”

None of this is profound, but all of it is true, and the fact that it was coming from Fred Astaire forced me to take it seriously. So many truly talented people fall by the wayside because they get discouraged and lose their joy, their intensity. It was Fred who impressed upon me the permanent value of maintaining a positive attitude.

We stayed close for the rest of his life. In the mid-1970s, he fell in love with the jockey Robyn Smith, who was more than forty years younger than he was. Fred asked me what I thought. “Look,” he said, “everybody thinks I’m crazy to want to marry this woman. What do you think?”

I remembered how much I had loved Barbara Stanwyck; I knew that age was no barrier to love, and I told him I was 100 percent for it. Actually, I told him what Spencer Tracy had told me: “Are you happy? Then that’s all that matters.” By 1980, when they finally got married, Fred was eighty and Robyn was thirty-six. I believe that, while Fred was alive, she was absolutely great for him.