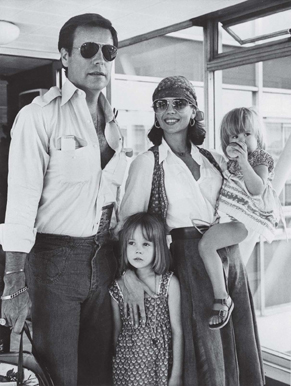

Arriving in London with Natalie and the girls, 1976. (STAFF/AFP/GETTY IMAGES)

After Colditz, the movies I made—The Towering Inferno, Midway—tended to make TV look better and better. Five years after It Takes a Thief went off the air, I went back to television. Natalie was now a full-time mother, and I was more than happy to become the provider. Switch was another caper show, about a partnership between a con man—me—and the ex-cop who sent him to jail—Eddie Albert. The two of us had a detective agency that specialized in conning con men. CBS was interested in the show because it bracketed two actors who had both been in previously successful shows—Green Acres for Eddie and It Takes a Thief for me.

Initially, CBS offered me the cop part, but I never wanted to play any character that could conceivably yell, “Freeze! Police!!” Every other show on television was a cop show, which makes a certain amount of sense because they’re perfect for TV. There’s a criminal, there’s a good guy, there’s a beginning, a middle, and an end. Anything that neatly schematic can be easily mass-produced.

But cop shows were too cut-and-dried for me, so I opted for the con man part, as well as a caper format, which requires more on the part of the writers and actors. Switch wasn’t a critic’s show, but the public liked it, and we ran for three years, from 1975 to 1978. It wasn’t easy, because CBS changed our time slot six times in those three years.

Eddie Albert was an interesting man who possessed what could legitimately be termed a big set of balls. Before World War II, he was a contract actor at Warner Bros. when he had an affair with Jack Warner’s wife, Ann. One time they were making love when Jack walked in and discovered them. As Jack told me, “I didn’t mind that so much; it was the fact that he didn’t stop that bothered me.” Well, that little episode got Eddie blacklisted for a while.

Then Eddie went into the service during the war and became a hero in the South Pacific. On November 21, 1943, when he was a lieutenant j.g. in the Navy, Eddie was stationed on the USS Sheridan when he commandeered four boats to rescue thirteen wounded Marines who were trapped on an exposed offshore reef at Betio Island in the Tarawa Atoll. He ordered three of the boats to hang back and return fire, while he took his boat in closer and loaded it up with guys who had been badly hit. Eddie had to make a couple of trips back to the Sheridan to get all the Marines to safety. He did all this under heavy fire.

Later, after the battle was mostly over, Eddie was in charge of body recovery when a last-stand Japanese sniper opened up on Eddie’s party. He and some other soldiers opened fire on the sniper and killed him.

Tarawa was savage; nearly 1,000 Marines died, and 2,300 were wounded. Of the 20,000 Japanese soldiers who were holed up on the island, only 17 left the island alive. For saving the lives of all those stranded Marines, Eddie earned a Bronze Star, and I think he could easily have been awarded more than that.

After the war, the times were such that even war heroes such as Eddie could get into political trouble—he was very liberal, and his magnificent wife, Margo, was even more so. But William Wyler helped bail him out by casting him in both Carrie and Roman Holiday, two totally different kinds of movies. Typically, Eddie was excellent in both.

I originally met Eddie and Margo through Richard and Mary Sale, who were good friends of theirs. Eddie was a complete actor. He loved the theater, he loved to act, and he could play drama or comedy with equal facility. He was a fierce environmentalist long before it was fashionable. As a matter of fact, Eddie was crucial in preserving the pelican population; the use of DDT was weakening the shells of pelicans in their nests, and the pelican population was cratering. Eddie threw himself into the fight to ban DDT. As soon as the chemical was restricted, the pelican population began coming back. To this day, whenever I see a pelican fly by on the Coast Highway, I thank Eddie Albert, and so should everybody else.

In almost all respects, he was an admirable man.

But with his life experiences, Eddie wasn’t fazed by things like stealing scenes, and he could be a bit devious and scratchy at times—about his character, his wardrobe, everything. Basically, he wanted to play both his part and mine, and sometimes he stole scenes for the hell of it. In his heart of hearts, he would have been very happy if Switch had been called The Eddie Albert Show. That said, I’ve always had affection for a theatrical rogue, and Eddie and I got along fine, mostly because if Eddie was going to steal scenes, so was I. Game on! For three years, we had a very pleasant competition.

Eddie was one of those veterans who didn’t talk much about the terrible things he had seen in the war, but thirty years afterward, just about the time we were working together, he had lunch with an admiral who had also been through the battle at Tarawa. When he got back to his hotel, he began shaking and collapsed into a terrible crying jag that went on for an hour. He had carried post-traumatic stress around for decades.

Switch was created by Glen Larson, and we had a great cast and crew. Universal was going to drop Sharon Gless from its contract list, but I met her and liked her. She never even auditioned for the show; I just thought she was perfect and hired her. Plus, we had Charlie Callas around for comic relief, and he was sensational. The chemistry was good, and the only real problem we had was that we went on the air before we had enough scripts, so the entire first year it was run-and-gun production and there was no time to get better writing.

In television, the most important component besides concept and casting chemistry is preparation—once the locomotive leaves the station, it never really stops until it reaches the end of the line, or the end of the season. That was a problem in the beginning for Switch. Because it was a show about con men, the writers were too focused on angles and gimmicks, and I was constantly pushing them for more characterization.

While I was working, our family kept growing. Along with Courtney there was Willie Mae Worthen, who started out as a housekeeper and quickly became part of our inner circle. Willie Mae was always there for the children, and she’s still there for them whenever they need her today, because she still lives with us.

One thing our remarriage gave us was a renewed appreciation of how much we loved the ocean. After Natalie and I divorced, I had spent very little time on the water, and neither had she. When she wanted to get out on the water, she’d charter a boat. We’d forgotten how important it was to our relationship, how the water nurtured and calmed us. Now that we had children, it was something we wanted as a continuing part of their lives as well.

It was during the run of Switch that Natalie and I bought our long-dreamt-of boat. She was sixty feet long and slept eight, and Natalie did the interior in early American. We called her the Splendour, after Splendor in the Grass, but with the English spelling to differentiate between then and now. There was also a motorized dinghy attached to the side that we called Valiant, in honor of the most embarrassing of my own movies.

From the beginning, the Splendour was less a yacht than a houseboat. Although Natalie didn’t particularly enjoy cooking at home, she enjoyed making huevos rancheros in the galley of the Splendour. It was a place for family and friends, and we were always loading it up with Tom Mankiewicz or Mart Crowley and some very special guest stars to cruise to Catalina or some of the other islands in the Santa Barbara chain. Some of the happiest days of our marriage took place on the Splendour because Natalie always enjoyed being on the water, although she was very nervous about being in it.

Elia Kazan came on the boat, and to my surprise I found that he loved to fish and was a terrific first mate. Perhaps I shouldn’t have been surprised; on Gadge’s farm in Connecticut, he enjoyed nothing more than climbing on his tractor and working the land. Gadge was very much of the earth and, as I discovered, of the water as well.

I think Gadge’s great gifts as a director derived from his curiosity and openness. He would talk to anybody, ask them, “What do you think?” and mean it. He took time with people, and because he was Elia Kazan, his attention really meant something. Personally, Gadge was always nudging me to focus my career on comedy; he thought my instincts for comedy were excellent.

But so many people hated Gadge because he named names during the red scare period in the early ’50s. I was with him in New York when people would walk up and literally spit at his feet. Then they would cross the street. And Gadge would just go on, as if what just happened hadn’t happened. He must have had some bitterness about this—some of the people who were the most hostile wouldn’t have had careers without him—but he never expressed it. He held it in.

Natalie and I were very attentive with each other. It came easily for us. She would write me notes on the anniversaries of our marriages or on my birthday. On my birthday in 1974, she wrote me, “This is always my happiest day, too—because of you. I love you.” That same year, on December 28, the date of our first marriage, it was: “This was the happiest day of my life in 1957—but I didn’t know you’d make me doubly happy in July of 1971.”

On my birthday in 1975, we planted a fig tree in the garden, and she wrote me, “This fig may look bare now, but soon it will bear fruit—as we have. I love you with all my heart and I hope this tree grows as beautifully as my love for you does every single day.” On Easter 1975, she wrote me, “Dearest, here’s to smooth sailing for us from now on! I love you with all my heart and it belongs only to you.” On Easter 1976, she wrote, “I love you more than love.”

Without question, doing Cat on a Hot Tin Roof with Laurence Olivier and Natalie was my professional high point. To work with Olivier, to see how he approached acting, and to observe his competitiveness, his refusal to be defeated by illness, age, or any other actor, was a pure privilege.

I first met him through Spencer Tracy, who had been friends with Larry for years. When Olivier came to America to make William Wyler’s Carrie, he worked with Spence on his accent to get the rhythm of midwestern speech. When Spence introduced us, I immediately took to Olivier, who was crazy about Natalie as an actress and as a woman.

My old friend Bill Storke created a series of specials called “Laurence Olivier’s Tribute to the American Theater,” and in the spring of 1976 we traveled to London and rehearsed for four weeks on Cat on a Hot Tin Roof, with Tennessee Williams in attendance. When Paul Newman and Elizabeth Taylor did the movie version with Richard Brooks, they couldn’t mention homosexuality or cancer, without which the story doesn’t make an awful lot of sense, but we went back to the original script.

It was a painstaking production; we had two weeks of costume tests before we started the month of rehearsals. Then we took nine days to tape it, working in complete scenes in front of four cameras. We were so prepared that we could have played that production on any stage in the world.

There were no private lessons with Olivier. He worked in hints. He told me to take my time, that I could sustain a moment. Maureen Stapleton was cast as Big Momma, but she would not fly. If it moved, she was nervous about getting on it. She was supposed to be in England with us to rehearse, but she had taken the Queen Mary and the ship had gotten held up by bad weather. She didn’t make it to rehearsal until three days after we had started.

Now, I had memorized the entire play before we started rehearsing. I had borrowed an office at William Morris in Beverly Hills and hired an acting coach to work with me. I wanted to be set, I wanted to be confident, and I also wanted to be free to watch Olivier work and not have to worry about my lines. So I was off the book when we started to rehearse.

Larry was using his script. He would say to himself, “Let’s see, I move here, then I go over there,” and I would be standing there, without my script, cueing him. It was Maureen’s first day at rehearsal, and she watched us working for a while, then took me aside during a break.

“What are you doing?” she asked.

“We’re rehearsing, Maureen.”

“Where’s your script?”

“I learned the play. I don’t need it.”

“That doesn’t matter. Take your script with you when you go out there.”

“But Maureen, I don’t need it, I…”

“Take it from a smart old Irish cunt, pick up your script. Don’t be a smart ass.”

I actually wasn’t trying to be a smart ass, but Maureen was adamant, so I did what she told me to do. Looking back, she was right; her point was well taken.

Tennessee Williams was working with Larry on the third act—always the problem with that particular play. Tennessee and Larry trimmed it down and did some polishing. I had met Tennessee years before, when I was shooting some scenes for The Frogmen in Key West. He made it quite obvious that I was his type, and I had to gently disabuse him of that particular notion. Tennessee was always a very vulnerable man, but when we were working on Cat he was an open wound, noticeably frightened of the critics and what they might say. He was not in good shape, and he was particularly upset with a ridiculous English quarantine regulation that had kept his beloved bulldog from accompanying him to England. As partial compensation, his friend Maria St. Just was always nearby, hovering and holding his hand.

Olivier was always a text-oriented actor, but he had a way of transcending that. What was truly interesting was how fresh he kept his performance. He didn’t lock in a performance at all; it varied from take to take. And like most of the people I have valued in my life, he was a very warm, emotional person, although I have no doubt he could be a killer if he thought it necessary.

There’s a wonderful story about Larry and Kirk Douglas on Spartacus. Now, Kirk Douglas’s ego is legendary even by the standards of the movie business. On Larry’s first day on the film, Kirk came to Larry’s dressing room on location to welcome him to the picture. But Kirk made the mistake of reminding Larry that, “in film, you don’t have to do a lot.”

Kirk was producing as well as starring in a very expensive picture, so his concern was understandable, but he forgot that he was talking to Larry Olivier. It was waving a red flag in front of a very wily bull. Olivier was not only fully professional but had made nearly twenty-five movies by then, including great work for great directors: Willy Wyler, Michael Powell, and so forth, not to mention producing and directing some pretty good movies himself: Henry V, Hamlet, and Richard III.

Larry innocently said, “Why don’t you do the scene for me, Kirk, so I can see your ideas?”

So Kirk gets up and does Olivier’s scene as he thinks it should be done.

“Splendid, splendid, Kirk. Could you perhaps just do it one more time for me?”

Once again, Kirk does Larry’s scene for him.

“Um, that was wonderful, Kirk. Might I ask you for just one more opportunity to study your movements?”

It was only after Kirk had done Olivier’s scene for him four separate times that he realized he was being put on.

Olivier was the least indicative actor I’ve ever worked with. “Indicating” is actor’s vocabulary for the original sin of forcing the audience to feel something. The goal is to make the audience cry, not yourself, and to do that you have to have the confidence that your emotion and your interior behavior and feelings can move somebody else. (This was Natalie’s great gift.)

When Olivier was doing Dracula with Frank Langella, I asked him how it was going. “A bit too much with the cloak,” he said.

That’s indicating, and the peril of costume parts is that the actor can rely on the costumes and props instead of communicating the character’s emotions to the audience. It’s also the most difficult thing an actor can do. You get up in the morning, and you’re thinking about the scene you have to do, and you keep thinking about it while you’re being made up. You tell yourself to keep the scene in perspective with the whole of the film and not to push it. And then you go on the set, and sometimes the director will say, “Act!” And that’s the thing you don’t want to do.

You do not want to act. You want to be.

The reviews for Cat on a Hot Tin Roof weren’t that good. Tennessee Williams’s career was at a low ebb, and I think the idea of a couple of mainstream Hollywood actors coming to London and working with Olivier set people’s teeth on edge. Too bad. It’s a fine play and ours was a very good production. I remain proud of Natalie and myself for tackling it.

Larry and Natalie and I had such a splendid time together that he eventually brought his entire family to be with us on the Splendour. It’s impossible to know what goes on in anybody else’s marriage, but Larry’s domestic situation was far from ideal.

In a biography that she authorized, Joan Plowright was very hard on Olivier for his ego and competitiveness. On the basis of the time they spent with us, I thought she was very hard on him—she was continually snappy and pettish. Larry was ailing—he was much older than she was, he had a debilitating skin disease, and he was still working hard to put money aside for his children. But she didn’t seem to want to make any allowances for his situation.

Larry wasn’t too tired to fight back, but he seemed to have made a private emotional calculation that it wasn’t worth the trouble. It was obvious that the main reason they were still together was their children, whom he simply adored. He was determined that his son Richard would go to UCLA, as he eventually did. Larry and Joan did not have a love match by any means, and I thought that he deserved much more sympathy and consideration than he was getting.

Years later, after both Olivier and Natalie died, my dear friend Steven Goldberg gave me a beautiful German shepherd as a housewarming present for the house my wife, Jill, and I built in Aspen. The dog was two years old at the time, and we fell in love with each other immediately. For the next eleven years he was the blood of my heart, embodying joy as well as a nobility of spirit and form. I called him Larry.