Jill and me on our wedding day, May 26, 1990. (PHOTOGRAPH BY ALEX BERLINER © BERLINER STUDIO/BEIMAGES)

I had gone from playing a charming rogue in It Takes a Thief to playing a charming rogue in Switch to playing a charming non-rogue in Hart to Hart. My public image was—and probably remains—a cross between Alexander Mundy and Jonathan Hart.

I realize that there are actors who bridle at being typecast; they find it limiting, or even insulting that the public fails to recognize their versatility. But about the time I was doing Switch I had a crucial realization. I was in Palm Springs, standing in a supermarket checkout line. A woman in back of me said, “Oh, how are you?”

“I’m just fine, thank you.”

“I’d like to invite you to come over to my house for dinner tonight.”

“Oh, I’m sorry, I have plans. But thank you so much for the invitation.”

“But I’m really a very good cook, and my husband’s a nice man. You’ll like him.”

Well, I managed to beg off, but I realized that something remarkable had just happened. This very nice woman wanted to invite me to her house. It struck me then, and it strikes me now, that this is lightning in a bottle. The public sees me as a member of their family. They love me and want me, not just in their living room, but in their kitchen or dining room. I was and am delighted. More than that: I’m honored.

When I was a kid watching movies in Westwood, I was in the dark, looking up at the screen at people who seemed more than human—larger, grander than life. I wasn’t talking to anyone—hell, I was barely eating my popcorn, because I was totally involved in that glowing silver frame on the wall. You didn’t actually imagine that you’d ever see Clark Gable in the flesh—that’s why I was so stunned that day at the Bel-Air Country Club. The proper response to actually seeing Gable or Cary Grant was gaping awe.

But when viewing habits changed, when more people started watching actors in their living room than in theaters—in other words, with the lights on and with occasional conversation—it signaled a sea change. As an actor, you were in people’s living rooms, and that meant you could be a part of their lives in a way that the great movie stars of my youth weren’t—if the people in that living room accepted you.

I don’t think it’s an accident that great stars like Jimmy Stewart, Henry Fonda, and Bing Crosby all failed on television. They were somehow too big for the medium, and in trying to scale down their personalities to be more domestic, more approachable, they lost what made them interesting in the first place. Jimmy Stewart’s volatility, the possibility of rage, was gone; likewise Fonda’s remoteness, which always translated as integrity. Great actors, great stars, wrong medium.

The change has continued, and not just at the movies. Now in a theater people are talking and cell phones are ringing. It’s one of the reasons movies are so loud—so they can be heard over the din of the audience. When I used to go on an airplane, I wore a jacket and a tie. Now people get on board in tank tops and flip-flops. For a half century, I worked in front of cameras loaded with film; now I work in front of cameras loaded with digital tape. It’s all changed, and some of it’s an improvement and some of it isn’t.

But one thing never changes: then and now, in movies or television, millions of people arrange their lives so that they can watch actors who mean something to them. For those of us lucky enough to be singled out, there can be no greater compliment.

Hart to Hart went off the air in 1984, and a year later I was back with ABC on a show called Lime Street. My part was not dissimilar to Jonathan Hart; this time I was a horse breeder who also investigated insurance fraud. I had two children and a father, played by Lew Ayres. I had admired Lew ever since I observed the quiet grace with which he endured being blackballed at the Bel-Air Country Club for being a conscientious objector.

Lew was pushing eighty when we did Lime Street, but the wonderful thing about good actors is that the varying ways in which they prepare themselves for work fall away when the director says, “Action.” Acting is acting. Men like Lew Ayres or Melvyn Douglas weren’t method actors, but no method actor would think Lew or Melvyn had anything to apologize for.

For an actor, there are two key questions: Do they believe me? Can I move them? Nothing else really matters.

Lew was always looking for the reality of a scene—the emotional truth. I loved working with him. He was a very good, kind human being. For years he had devoted himself to a study of comparative religions and the different ways people worship God, but near the end of his life he switched to something a little more quantifiable: meteorology.

One of my daughters on the show was played by Samantha Smith, the little girl from Maine who had become famous when she wrote to Yuri Andropov, the leader of the Soviet Union, urging peace. Andropov had then invited her to Russia for a lot of Kodak moments.

Lime Street was a good idea, and I loved Samantha Smith, although I can’t take credit for her presence in the show—casting her was the idea of Linda Bloodworth-Thomason and her husband Harry, who were producing the show and who had brought in sufficient budgets to allow for European location shooting. I kissed Samantha good-bye on Piccadilly and flew to Gstaad for some location shooting. Samantha and her father were flying home to Maine, then were due to quickly turn around and come to Switzerland to join the shoot.

When I got off the plane in Geneva on August 25, 1985, they took me to a private room, where Ray Austin was on the phone from Gstaad. It was Ray who told me that Samantha and her father had been killed in a plane crash. This lovely, gifted child was thirteen years old.

It was as if the breath left my body. My own kids and Samantha had played all the time. She had a career and, more importantly, a life ahead of her that would have been wonderful. I had just said good-bye to her the day before. I had given her a bracelet that became one of her treasured possessions; she never took it off, and she had been wearing it when she was killed. It was another stunning death in my life.

By the time I recovered my equilibrium and got to a phone, Columbia, the studio that was producing the series, was already making noises about recasting her part. I said flatly that I wasn’t going to be party to that. I went to the wire services and told them I was closing production down, and that was the end of Lime Street. Harry Thomason and I flew to Maine for Samantha’s funeral. Her mother was wearing the bracelet I had given Samantha.

The first episode of Lime Street ran on September 21, the last on October 26.

Columbia continued to behave very badly. Samantha’s tickets had been bought from American Express, and the studio didn’t want to acknowledge that she was being relocated for the show. They should have just shut up and made a settlement, but they fought it by saying that she wasn’t on the company payroll at the time, even though she was flying to Maine to pack up and go back to Europe for studio work.

This went on for a couple of weeks, and one day as I was driving to the studio for a conference, I noticed that I was gripping the wheel so tightly that my knuckles were white. Finally, I told the studio that if this matter went to court, I would testify for Samantha’s mother and I would make sure to bring as many of the press as I could get into the courtroom.

With the exception of Natalie’s death, Samantha’s death and its aftermath was the most emotionally upsetting thing I’ve ever gone through, and it drained a lot of the affection I always had for the business.

Lime Street would be the last TV show I starred in, and that wasn’t by accident. I’ve continued to appear in TV movies and individual shows, and a few series ideas have come up that never came to fruition, but those were all ensemble projects, not shows in which I would pull the train. Samantha’s death and what came after were the events that finally convinced me that it was time to begin a judicious retreat from the business that had defined my life.

Also contributing to my disaffection was my terrible disappointment in the Thomasons. They wanted to run the show their way, and their way was the way it had to be. I had heard incredible stories out of the set of Designing Women, and most of them turned out to be true.

We had been shooting in Amsterdam, and Ray Austin, a great and loyal friend who had directed a lot of Hart to Hart, and I had gone over the rushes on tape, making notes. When I got back to California, I found the box of tapes and notes sitting unopened in Harry and Linda’s offices. They had no interest in anybody’s ideas but their own. As it turned out, Designing Women was their lightning in a bottle; nothing else they ever did really succeeded on that level.

I am indebted to them for one thing, though. They introduced me to Bill Clinton. A few years before he was elected president, he came over to the house for three hours, and we talked about everything under the sun. I have seen a lot of people in Hollywood who have lofty ideas about their own charisma and fancy they can work a room. Occasionally, I’ve imagined I had some skills in that regard myself. But I have never seen anybody who’s the charming equal of Bill Clinton.

After Lime Street, I remained in high demand and threw myself into producing a lot of TV projects. Throughout the years that followed Natalie’s death, work did what I hoped it would. Everything in my life had stopped, and I had to rebuild myself piece by piece. Throwing yourself into work does many things, but mainly it embeds you in a different reality, one that’s more manageable than the one you’re avoiding. A couple of the TV movies—a form I like a lot more than series—were very good, and the run of projects culminated in six two-hour Hart to Hart TV movies.

It was a great deal of fun to be reunited with Stefanie Powers and Lionel Stander, although the changes in the business created some resistance to hiring Lionel. The studio thought he was too old. “What if he dies?” some executive asked me. “If he dies, we’ll write it into the shows,” I said. I pointed out that Lionel was a large part of the show’s chemistry and that, aside from being disloyal—and I don’t believe disloyalty should ever be tolerated—it wouldn’t have been Hart to Hart without him.

I concluded the conversation by saying, “If you’re not interested in having Lionel in the show, there will not be a show. I will not make Hart to Hart without him.” That ended the conversation, but it was not a conversation I should have had to have.

Among the stand-alone projects, I was particularly pleased with There Must Be a Pony, which had been a very good novel by James Kirkwood Jr. It was a roman à clef about his mother, silent film star Lila Lee, and her affair with the director James Cruze—one of those negatively symbiotic relationships in which each party increased the speed at which they were heading for the bottom. Jimmy Kirkwood was a delightful man—flamboyant, funny, and self-deprecating. He cowrote A Chorus Line, the best musical I’ve ever seen, and I’ve seen them all.

I asked Mart Crowley to write the script, and it was his excellent work that helped me sign Elizabeth Taylor as my costar. I was already with Jill when we made There Must Be a Pony, and I was concerned that Elizabeth might be interested in rekindling our relationship, but nothing happened.

I hired Joseph Sargent to direct the picture, and before we got started we talked over everything thoroughly and rehearsed the staging and the attitudes. As soon as we started shooting, Joe changed everything. He became an impulsive egomaniac, and I wondered why we bothered rehearsing for two weeks if he was throwing everything we had agreed on out the window.

If it had been a feature, I would have fired him, but on a television film that’s very hard to do because the schedule is so short. My main worry was that Joe wasn’t leaving Elizabeth alone; he had completely altered what he wanted from her, and I thought the way we had planned her performance in the first place was wonderful.

I knew that if he lied to her, she would kill him and, by extension, the entire film. She would kill him with time—take an hour and a half to make up one eye, that sort of thing. The problem was that I had personally guaranteed the production—the insurance company didn’t want any part of Elizabeth because of her long history of health problems. Any overshooting was on my tab, and if Elizabeth decided Joe had to be shown who the real diva was, I was in danger of a financial bloodbath.

Well, Elizabeth showed up every single day and was totally professional, even though her director wasn’t. She was perfect in her lines, perfect in her attitude, perfect in her performance. We went over schedule by one day, because of a problem at Hollywood Park that was unavoidable, but it was a smooth production and a fine film—in spite of Joe Sargent, not because of him.

The experience of working with her confirmed my feeling that Elizabeth Taylor is one of the best screen actresses ever, a fact that has been overlooked because of her beauty and because her private life has clouded the public’s perceptions of her ability as an actress.

It was at this time that I had another insight into the simmering rage of the red scare period. I was proud of There Must Be a Pony and had a screening at Warner Bros., after which we had a party at my house. I had unthinkingly invited two people who meant a lot to me: my old director Eddie Dmytryk and Lionel Stander. Eddie had been one of the original Hollywood Ten and had gone to jail for his beliefs, after which he recanted and named names. Lionel, of course, had stood firm. They both came to the house, and each refused to acknowledge the other’s existence. For the whole of the evening, they stayed far, far apart, all because of shameful events of forty years before, when good people were asked questions they never should have been asked and saw their lives torn apart.

I had asked Howard Jeffrey to produce There Must Be a Pony. Howard was always there for Natalie, and he was always there for me after she died. I trusted Howard absolutely; I made him executor of my will and gave him the responsibility of raising my girls if anything happened to me. But the day came when Howard came to me and told me he was terribly ill with AIDS. It was typical of Howard that he was less worried about himself than he was about us. “What can I tell the children?” he asked me.

In the lives of the people who loved Howard, there will never be anybody to replace him.

My next project was a TV film with Audrey Hepburn—her only movie for television. I had met Audrey shortly after she came to Hollywood and was always mad about her. The project we worked on, Love Among Thieves, was a lighthearted charmer about an elegant lady—Audrey—and a raffish, cigar-chomping guy—me.

The network had offered the man’s part to Tom Selleck but he couldn’t do it, and when Audrey told them she wanted me, I jumped at it. Audrey was sensational to work with: professional, relaxed, engaging, endearing—the most helpful, loving person you could imagine. She had finally jettisoned her second husband, a psychiatrist who wasn’t any better for her than Mel Ferrer, her first husband, had been. Somewhere in there she had had a major affair with Ben Gazzara, and I understand that when she left, it brought him to his knees, which I could certainly understand. When we made Love Among Thieves, she was with Rob Wolders, with whom she stayed for the rest of her life. Rob gave Audrey something she had always needed and had never gotten—security. He wasn’t with her for the glory and perks that came to the consort of Audrey Hepburn. He was there because he loved her, and he was at all times attentive, loving, and caring. Simply, he made her very happy, which is what she had always deserved.

It was a good picture and a good group of people—Jerry Orbach and Samantha Eggar were also in the cast. But I don’t believe that any of Audrey’s pictures were as important or as meaningful as Audrey. Audrey’s essence as a human being shone through her acting and lifted her movies up by yards, not inches or feet. I have never known any woman other than Jill whose personality was so reflected in everything she did.

Audrey’s spirit was embodied in her garden, her furniture, her paintings, her jewelry, her dogs, her linens. She absorbed everything she experienced and saw in her life, took it into her subconscious, her soul, and then somehow contrived to radiate it outward onto everything she touched. If I were to show you four or five pictures of different houses and gardens, you could easily pick out the one that was Audrey’s place in Switzerland—it reflected security, serenity, and, through the beautiful flowers on which Audrey lavished so much attention, astonishing beauty.

There Must Be a Pony and Love Among Thieves were both rewarding experiences, but a couple of the TV projects weren’t as good as they could have been. Indiscreet had been a good picture with Cary Grant and Ingrid Bergman, and I wanted to do a remake with Candice Bergen. But the network said they wouldn’t make the picture with her. “She doesn’t have any humor, and she’s an ice queen,” they told me. So a year later, Murphy Brown went on the air and proved that she was never an ice queen and had a spectacular sense of humor. Unfortunately, I had to do Indiscreet with Lesley-Anne Down, who I found opinionated and irritating.

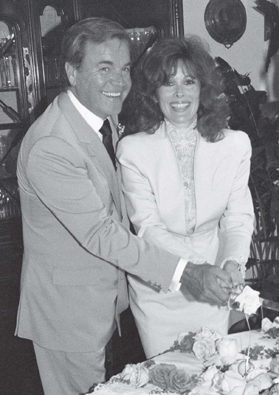

The capstone to this phase of my life came when Jill and I were married under the two-hundred-year-old sycamore trees in the back garden of the Brentwood house on May 26, 1990. Roddy McDowall brought his video camera and shot what seemed to be endless hours of the ceremony and the toasts of the guests, intercutting them with shots of the house and the ranch. To the best of my knowledge, the only people who sat through the tapes in their entirety were my mother, Jill’s mother, and Willie Mae. They watched the tapes incessantly, saying over and over, “Oh, look at that! Isn’t he/she adorable?” My son Peter Donen, as well as my daughters Katie and Natasha, would also be married under those trees.

The years since have been the most serene of my life.

I always had a sneaking affection for Aaron Spelling. He was a bug-eyed, asthmatic Jewish kid who grew up in Texas and got the shit beaten out of him by the other kids damn near every day. Not only was he a Jew in Texas, he was a little Jew in Texas. He grew up, went to Hollywood, was mentored by Dick Powell, and became a billionaire. A great story.

But Aaron and his partner Leonard Goldberg and I had epic battles over the years. A lot of them were over the profits due me and Natalie over Charlie’s Angels, and a lot of them ended up in court. I’m proud to say I won nearly all of them.

This went on for decades! In the spring of 1980, Los Angeles County District Attorney John Van De Kamp, who had successfully prosecuted David Begelman for forging checks in 1978, began an investigation into the business practices of Spelling/Goldberg. Van De Kamp believed that $660,000 due Natalie and me from Charlie’s Angels had been “reallocated” to the accounts of Starsky and Hutch, a show that Spelling/Goldberg owned a much larger piece of. Charlie’s Angels was then in its fourth year, and we hadn’t received any money from it at all at that point, which is not unusual—most TV shows run a deficit until they go into syndication, which is where the real money is.

I couldn’t say anything about the investigation publicly, for the very good reason that Aaron and Leonard were also our partners in Hart to Hart. As it worked out, Van De Kamp never brought criminal charges against Spelling/Goldberg, but he did advise all the profit participants on their shows to hire independent auditors to make sure they got what was coming to them.

All this was classic creative bookkeeping and, sad to say, classic Hollywood. Years later we had a fight over the profits from Hart to Hart. There were other profit participants besides me—Stephanie had been hired as an actress on straight salary, but I thought she deserved more and gave her a piece of my piece of the show. Tom Mankiewicz was also a profit participant. My problem was that I was sick of having to fight for what was contractually mine, so in a moment of anger I had called Leonard a crook. We were sitting there in a lawyer’s office trying to work things out. The lawyer outlined the situation, then Leonard said, in a hurt tone, “I’m not a crook, and I don’t want anybody calling me a crook.”

We then went around the room so everybody could lay out their position. The statements told you a lot about each individual’s character.

Tom said, “I think you owe me money.”

Stefanie said, “There’s a great deal of poverty in the world, and so many want for so much. We’re all fortunate to have as much as we do, and I just hope we can all work it out.”

I chimed in with, “Leonard, you’re a fucking crook.”

We worked it out. Aaron finally said, “Let’s pay the money and get on with our lives.” But having to fight for what is rightfully yours is not fun, even though it’s all too often a necessary part of Hollywood.

Years ago, I was having a drink with William Holden and Cliff Robertson after a day of shooting The Mountain at Paramount. Out of nowhere, Cliff said, “Jesus, Bill, what does it take? What does it take to have a career like yours?”

Bill Holden thought about it for a few seconds and then said, “Well, you have to have it.”

“It?”

“It. You know, Sunset Boulevard.”

He meant that you have to have that one signature part in that one signature picture, the picture that defines your screen personality and your career. That never quite happened for me in the movies, although I certainly had signature parts in television.

I had a couple of near-misses. Butch Cassidy and the Sundance Kid was dangled in front of me for a while, but then it went away. Robert Evans wanted me and actually cast me in Rosemary’s Baby, as Mia Farrow’s husband, but Universal queered the deal by refusing to hold off production on It Takes a Thief. John Cassavetes got the part.

Paul Newman and Robert Redford were sensational in Butch Cassidy, so I can’t say I would have done any better, although I have to confess to a tight little feeling of continuing disappointment when I think about playing that part. Losing that one hurt. Without false modesty, I think I would have been considerably better in Rosemary’s Baby than Cassavetes. One look at Cassavetes and you know he’s a minion of Satan, but I could have brought something else to the plate, something more deceptive. And I would have looked more believable with Mia Farrow as well.

When I lost Rosemary’s Baby, I was upset, but I wasn’t suicidal. I tried everything to make it work, and nothing could be done to make it work. Let it go. I was disappointed, but there are moments like that in the life of every actor. Also, if you’re going to be an actor, and if you want to have a long career, you have to make a crucial mental adjustment, and that comes down to: “It’s not me. It’s them.” I can do only so much to get a part, whether it’s Butch Cassidy or Jonathan Hart. They either want you or they don’t, and once you realize that, it’s helpful because it takes some of the burden off you.

If I lost a gig, it wasn’t the end of the world. I could always stand in a river with a fishing rod or play golf. My life now is not show business; it was when I was young, but the deeper I got into it, the more time I spent with people like David Niven, Claire Trevor, and Sterling Hayden, the more I realized how important it is to have something else in your life, something that can fuel your acting.

Otherwise, this is what happens: You get a pool, and you need a pool man; you get the larger house, you need the staff to cover it. And gradually you find that you have to start taking jobs that you might not really want in order to cover your overhead. Abe Lastfogel put it best when he told me, “Once you get a pool, they got you.” I can think of hundreds of people I’ve known in the movie business who got what they thought they wanted, only to find out they didn’t want it after all, but it was too late to get off the merry-go-round. Not good.

Ultimately, I think it was David Niven who made me realize that a life has to encompass more than show business; David shaped his life, and acting was just one part of it. He liked to sail, he liked to fish, and he enjoyed people tremendously. The next part, the next movie, was not at the top of his list of priorities. And my children have been very important in providing a different horizon for my life. There are no negatives to children. There are disappointments and concerns—terrible concerns, as any parent will recognize when I say that if the phone rings after 10:00 P.M., I levitate out of the chair to a height of at least three feet. But my children are more than my loves—they’re my pride and sustenance.

Jill was also a major contributor to this realization. She knew that the importance of show business is transitory and that life involves more than whether or not photographers go crazy when you show up at a restaurant. She was less concerned about her career than I was, and she had a way of drawing me back a bit to enjoy the fruits of the life I had built over the previous thirty-five years. You can luxuriate in a garden and watch the different way the light hits the mountains as the afternoon wears on, or you can get on another airplane and make another movie.

The latter will fill your bank account, but the former will fill your soul.

Claire Trevor died in 2000. Before she passed away, she designated a group of people who had meant a great deal to her and left each of us a gift of money in her will—what she called “a hug and a kiss” that she was unable to deliver in person. Since Claire was partially responsible for my appreciation of art, I used some of the money to buy two sculptures from nature: a bear, which I have in my bedroom, and a pair of owls. With what was left over, the next time I was in Paris I went to a caviar bar that she had introduced me to, ordered some fine caviar and a bottle of champagne, and drank a toast to a great, great lady.

By 1990, I was open to other things besides television, so Stefanie Powers and I began touring with A. R. Gurney’s play Love Letters. I hadn’t been on the stage since Mister Roberts a quarter-century earlier, but the more I thought about Love Letters, the more I had to do it. For one thing, it was a part I identified with—I was raised in camps and boarding schools. I knew Andrew Makepeace Ladd III, and I knew his WASP background. And I could also relate to his constant pursuit of one woman, and his ultimate loss of her. It’s such a well-written play, and it’s so very sad.

Stefanie and I did the play in a rolling series of one-nighters for about five years, five or six consecutive shows in a week, then three weeks off. In 1990 we took the play to London and did it for six weeks at the Wyndham Theatre in the West End. The reviews were terrible, but I knew they would be because I know how critics think. Two American TV stars who sit down on a bare stage and read letters? In the land of Shakespeare? Not bloody likely. But I honestly didn’t care; I was playing the West End in front of sold-out houses, something I never thought I’d do.

After five years, Stefanie became a little worried about becoming a permanent double act. She invoked Laurel and Hardy, and I still can’t quite figure that out, perhaps because I’ve always loved Laurel and Hardy. So Stefanie stepped out, and I asked Jill to step in. She initially refused, because she didn’t want to be compared to Stefanie and because she hadn’t been on the stage since she was a child.

“How many actresses have done this part?” I asked her. “Dozens! The part’s never been identified with any single actress.” She thought about it, then said yes. Jill and I did the play together for nine years, from 1995 to 2004.

On balance, I think Jill’s performance was more real than Stefanie’s. Stefanie is more theatrical; when Stefanie is in England, she becomes English, complete with accent. She has an incredible ear and picks things up automatically, and because of that, her emotions can be in a constant state of flux.

Whether I was doing it with Stefanie or Jill, it was very hard work. Not the play—that was a constant joy—but the traveling. Because it was mostly one-nighters, I realized after a time that I wasn’t being paid to act, I was being paid to travel.

If at all possible, we’d use a hub system that Jill developed. If we were playing towns in Illinois, we’d stay at the Four Seasons in Chicago—Jill picks hotels by how good their room-service eggs Benedict are. Every afternoon we’d drive to the airport and head for someplace like Springfield or Joliet, and we’d come back that same night. That way, we could spend five or six nights in the same hotel, although there were lots of times when that wasn’t possible and we’d be at an airport twice a day.

Other than the travel, it was a totally positive experience. One of the high points was the month we played in Chicago to great reviews. We were the hot ticket. I told Jill, “This doesn’t happen often. Enjoy it.”

I loved that play. To be able to sit down and say words, without the crutches of music or scenery, just words, and have those words move thousands of people every night so that they were stunned and in tears and standing up and applauding—there can be no greater reward for an actor.

I remember when we opened at the Wilbur Theater in Boston, the director gave us a note: “Don’t play it. Just read the letters and let it happen.” And that’s exactly what we did, bringing our own emotional coloring as actors and through that discovering the layers of the characters, and the layers of ourselves. I never looked at Jill onstage, and she only looked at me once, at the very end. We had some extraordinary nights. We found new values in that play every night. Every night!

We took the images of different people out onstage with us. In Jill’s case, it was the young Barbara Hutton. Barbara had been Jill’s mother-in-law when she was married to Lance Reventlow. Barbara was one of those people who didn’t like to be alone—a woman whose life just didn’t work out. Jill never particularly liked her, but she admired her wit and intelligence and felt sorry for her. Occasionally, Barbara told Jill stories about her terrible childhood, and in Jill’s mental image of her character, she was similar to the “poor little rich girl” that Barbara Hutton had been.

We covered America two or three times over, played Europe, played Atlantic City twice, Vegas three times. We played casinos, we played basketball stadiums, we even played synagogues. We played everything but a men’s room. When we played in Texas, words like “fuck” and “snatch” lifted some people in the audience right out of their chairs, out of the theater, and into their cars. Alabama had the same response. When we played the synagogues, Jill took those words out of the script. “I’m not saying ‘snatch’ in a synagogue,” she told me. Other than that, we never changed a word of Gurney’s script.

Paul Newman and Joanne Woodward and I had some discussions about doing Love Letters with a revolving cast. One night it would be Paul and Jill, another night it would be me and Joanne, and just to keep things really interesting, every third night Paul and I would do it. Just kidding. The revolving cast never happened, but I still think it was a good idea.

After Stefanie Powers and I had done six Hart to Hart TV movies, I was offered $10 million to produce three more. It seemed like a good idea to me, and Lionel Stander and the rest of the team were up for it, but Stefanie opted out in favor of doing a road company of the musical Applause. I was furious at her decision, regarding it as a betrayal—not just of me but of all the cast and crew who had worked with us for years and certainly could have used the work. But Stefanie had come to believe that Hart to Hart had typecast her and the show was somehow holding her back. There was some halfhearted conversation about recasting her part, or even writing her out of the shows, but I pointed out that if we did that, it wouldn’t be Hart to Hart anymore. I felt I had to be loyal to the audience’s expectations. I walked away.

Applause closed quickly, and I suppose we could have reconstituted the Hart to Hart TV movies, but I had lost interest in working with Stefanie. Last year, her agent called to ask if I would be interested in doing a reunion Hart to Hart project. “Who the hell wants to see people our age cuddling in bed?” I asked him. I love Angela Lansbury, but I’m not about to give her a run for her money as the oldest detective in television history.

Mostly, I’ve continued to work as much as I want. A movie or two a year, a couple of TV shows a year. Lately, the biggest hits I’ve been associated with have been Mike Myers’s Austin Powers movies. I met Mike when I hosted Saturday Night Live in December 1989. At that point, Mike and his wife, Robin, were living in a tiny apartment in New York, and she cooked for them on a hot plate. I had a great time on the show, and I did a couple of skits that Mike wrote, in particular a hilarious bit playing a gay nurse—Nurse Stivers.

Years went by, and in 1997 Mike sent me a script he’d written about a secret agent from the Swinging Sixties who was cryogenically frozen and became the ultimate fish out of water in the modern era. I was to be the jealous second-in-command to Dr. Evil, Mike’s take on James Bond’s nemesis Blofeld.

Austin Powers looked good on paper, and it looked better on film. Everything you saw in the film was in the script—my eye patch, everything. Mike is extremely shy but fantastic to work with—he knows exactly what he wants. Those pictures are definitely Mike Myers productions—Jay Roach is the credited director, but Mike calls the shots and does the editing. The success of the film, and the notice people took of me, confirmed Gadge Kazan’s suggestion that my instincts for comedy were excellent and I should do more in that line.

The odd thing about the Austin Powers pictures is that they sometimes look like we’re improvising, but we’re not. Everything’s written. I did feel that on Austin Powers in Goldmember, the last of the trilogy, the script was better than the film. There were some terrific scenes that ended up getting cut, including one of all of us in drag singing, “What’s it all about, Alfieeeeeee…,” and there was another sequence with me and a herd of llamas that was quite funny.

Mike’s brand of comedy certainly pays dividends for a modern audience, although my favorite kind of comedy comes out of reality. The people I grew up laughing at, like Buster Keaton and Laurel and Hardy, usually started with a very realistic premise. That tradition was carried on by Blake Edwards, who I think was the best comedy director of his generation.

With all the quantum changes in show business—the transition to multinational conglomerate owners and the growth in foreign audiences, which affects the way a lot of movies are made—one thing hasn’t really changed since I drove onto the Fox lot in 1949: it’s a brutal business.

Just like sports, show business is for front-runners: they either boo you or applaud you, and it changes day to day. It’s particularly hard for actors. Logistically, a writer needs nothing more than a legal pad in order to write, but an actor needs a stage or a camera. Basically, someone has to hire him, and that changes the dynamic because it becomes money-intensive; it’s less of a talent issue and more of a sales issue. Add to that the fact that very few films are made because people have a passion to make that film. Mostly, films exist because corporations think they will be profitable, which results in a very different kind of movie.

In any case, I’ve been an actor for nearly sixty years, and nobody with that kind of career has any cause to complain. I’ve been very fortunate, and I think it’s largely because I was determined to be a working actor, emphasis on working. I just kept going to the plate and swinging. It didn’t matter whether the reviews were great or terrible, whether the films and shows were successful or unsuccessful. I kept showing up. Some actors go into a depressive shell when something doesn’t work, as if a critical or commercial failure is somehow a reflection on them and their ability. I’ve never believed that.

When I was a kid and just starting out, I read my reviews, but I came to realize that if you believe the good reviews, you have to believe the bad ones. Rather than focusing on what other people thought of me, I chose to concentrate on the work, the job, and my commitment to that work. I was at the studio, I was on time, and I knew my lines. As Spencer Tracy told me more than a half-century ago, don’t worry about anything but the scene. I extrapolated that to the big picture. From focusing on the scene, I focused on the job, then I focused on the next job.

Beyond anything else, I loved the business, and I loved working. And I don’t think people understand how important behavioral choices—not being an asshole, showing up on time, knowing your lines—are to sustaining a career. It’s easy to go from job to job when you’re hot, but it’s when things cool down that you can spot the jerks, because nobody will hire them.

I’m amazed that I’ve sustained a career for this length of time, because my contemporaries are either dead or haven’t worked in twenty years. The young actors with me at Fox were Cameron Mitchell and Jeffrey Hunter. Chuck Heston was at Paramount. Farley Granger was at Goldwyn, and John Erickson, who got the part in Teresa and got hammered for his trouble, was at MGM.

But the ironic reality is that no matter how devoted you are to your craft, it won’t necessarily have anything to do with whether or not lightning strikes. That’s actually a matter of the right part. Bill Holden, for instance, was not fully respectful of acting, but he got two films with Billy Wilder, and they changed his career and his life. Bill was a bit like Errol Flynn: he was ambivalent about his career choice but followed the path of least resistance and had a lot of doubts about himself as a result.

All my life, when I think about acting, I think about Spencer Tracy. Spence knew his work. He would say, “You’ve got to know the lines. If you know the lines, you can do anything you want to do.” Actors are really the least rehearsed of performers. The performers who really rehearse are musicians; they have those notes down, and that’s why they can go anywhere they want.

I remember sitting with the cellist Lynn Harrell. He was fretting about a problem he was having with a section of a piece. “I’m just not playing it the right way,” he said. The conductor offered some suggestions, and then Lynn said, “I know! I’ll think of Picasso.” These guys have played the music so many times that the problem of getting a fresh sound is in the forefront of their minds. The same thing happens with actors, except very few actors know their lines the way musicians know their notes.

I try to maintain a positive outlook about all the changes in the business and in the world, but I don’t like entitlement: kids who are pissed off if they don’t get into Harvard, Yale, or Princeton; actors who think they have to get where they’re going by the time they’re twenty-five because they’re afraid it won’t be there by the time they’re thirty-five. Recently I was talking to a young actor, and he mentioned a director he said was great because “he didn’t get in my way.”

This is insane. Acting is a give-and-take between the director and the actors. You have to have someone say the lines to you in order to prompt your lines. If that other actor is good, he will make you better, and if the director is good, you will be better still. But there are actors today who don’t care about that reciprocal arrangement. Their attitude is, “Fuck ’em, bring in somebody else.” These kinds of people are more concerned about their status than they are about the quality of the job they’re doing.

I’ve worked with guys who do push-ups or run around the block before a scene to work themselves into the proper state, but I tend to think that acting is analogous to music. When you hear a musician blowing a great sound, you don’t think about everything he’s gone through to be able to create those notes. You’re just interested in the result. The audience isn’t interested in what the actor goes through; they’re only interested in being transported, in being moved, and that’s what I find most thrilling—moving somebody.

After nearly sixty years, at this point it’s supposed to be Miller Time: hit the marks, say the words, go home. But I’m still nervous, and I still want to be as good as I can possibly be. The problem is not unlike Lynn Harrell’s: you want it to be there, but you want it to have a different value without pushing it.

I think my ability to sustain a long career has been at least partially a result of my ability to sustain long relationships, sometimes through succeeding generations. I’ve mentioned how much I valued Paul Ziffren, my lawyer. He was so innovative, so brilliant. It was Paul who set up the deal for Charlie’s Angels, and Paul who set up my profit participation in Hart to Hart. When Paul died, I simply moved my representation over to his younger brother Leo, who has fought my battles with all of the consideration, purposefulness, and accomplishment that his brother brought to my career. When Jill and I got married, it was Leo who gave her away. And Paul’s son John, who began his career in show business as a production assistant on Hart to Hart, is now a successful producer.

Fifteen years ago, after I’d fallen out with my agent, my daughter Natasha suggested I consider a man named Chuck Binder. Fifteen years later, on nothing more than a handshake, I’m still with Chuck, who has always had an overall view of my career and what I can do. I think Chuck is a large part of the reason I’m still working when most actors my age are sitting around twiddling their thumbs.

And then there are the friendships that have lasted longer than most people have been alive. Friendships are particularly difficult to sustain in a competitive, migratory business like show business. I’m thinking of people like the late Guy McElwaine, and Steven Goldberg, the man who gave me Larry, my German shepherd—actually imported from Germany by Steven. My friendship with Steven began as a straight business deal when he hired me to represent his company, but we began playing golf together, and more than fifteen years later we’re still doing it. We’re bound together by our love of dogs and golf and by similar senses of humor—the trifecta! I’m lucky to have him in my life. More than that—I’m grateful to have him in my life.