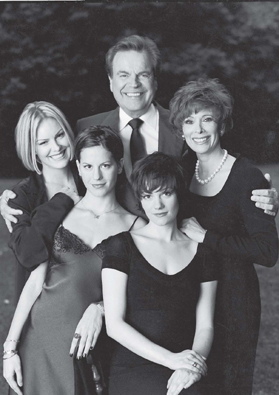

The extraordinary women to whom I dedicated this book: my wife, Jill, and, from the left, my daughters, Katie, Courtney, and Natasha. (© SAM JONES/CORBIS)

Any long life is pummeled as you lose the people you love, and because I’ve always been comfortable with an older generation, I’ve lost more than most. The last time I saw Noel Coward was in London at a party Swifty Lazar gave for him. Noel was very shaky, and Roger Moore and I helped move him around. At one point Roger and I were sitting at Noel’s feet, and he leaned down and told me, “I think this is my last party, dear boy. Don’t think there will be any more.” A little while after that, he went back to Jamaica to die.

I was living in the desert in the mid-1970s when Darryl Zanuck came back from Europe. His health was breaking down, and mentally he wasn’t what he had been. Virginia, his wife, had been waiting for this moment for twenty years, since Darryl left for Europe. She had always been Mrs. Darryl Zanuck, and she would always be Mrs. Darryl Zanuck. She took him back, and no man could have been more tenderly cared for in his last years. When I would go to see him, he knew who I was, but not a lot more.

In some senses, it was a sad and disconcerting end, but God, look at the bigger picture. Darryl created a great movie studio out of his own blood, sweat, and tears, and he made dozens of great movies that audiences are still analyzing, still being moved by. Darryl’s life mattered.

In addition, Darryl’s son Richard became one of the finest producers of his generation, which nobody could have foreseen when he was just the kid I used to play with at Darryl’s house in Malibu. People outside the business don’t know how difficult it is to follow an act like Darryl’s, but Dick Zanuck is the only mogul’s son to have a career comparable to his father. He’s a great producer (Jaws, Driving Miss Daisy, Sweeney Todd, and dozens of others), a standup guy, and, when Darryl was alive, he was also a wonderful son.

Gene Kelly and I were never lucky enough to work together, but we played a great deal of tennis over the years, and we enjoyed many skiing vacations with our kids in Sun Valley. Gene was a wonderful man with great joie de vivre, terribly active and athletic, and one of the most competitive personalities I’ve ever encountered. But Gene had some bad luck in the later stages of his life. He had a very nurturing marriage to Jeanne Coyne, a dancer, a glorious lady who had had the misfortune to be married to Stanley Donen at one time. Gene and Jeanne had two children, to whom they were completely devoted.

But Jeanne died in 1973. Gene’s career was winding down, the kids grew up and moved away into their own lives, and he was lonely. He married a much younger woman who was universally disliked by all of his friends and family. Then Gene’s health broke, and he lost his eyesight and the use of his legs. To see a man like Gene Kelly confined to a wheelchair before his death in 1996 was one of the most prominent examples of nature’s cruelty.

The deaths of these great friends might have been expected; they had run their race. But the death of my son Peter Donen in 2003 was stunning. Peter was still a young man, only fifty years old. He had become overweight and hadn’t had a checkup for a couple of years, and his loner personality worked against him.

Peter had become one of the finest creators of special effects who ever lived. You can see his work in movies like The Bourne Identity. Peter’s work was so seamless that critics commented on how nice it was to see a movie without computer images, even though The Bourne Identity was full of Peter’s computer images. Peter was almost a genius, and his great gift was that his special-effects shots couldn’t be identified as special effects. I loved Peter, as I do his brother Josh. Peter wanted me to adopt him, but I told him it was impossible because his father would never allow it.

In retrospect, I should have done it anyway.

My ex-wife, Marion, and I remain good friends, bound by our mutual love for our daughter.

There aren’t that many people left from the period when I broke into the business. Tony Curtis and I were friends for a long time, but we had a serious breach over the way he treated Janet Leigh. Janet was a considerable person, and Tony treated her badly, and said all sorts of nasty things about her. At that point, I got angry and told a Los Angeles Times columnist named Joyce Haber that none of that was true, that Tony was an asshole and she could quote me. Which, with a few emendations, she did. Tony blew up and challenged me to a fight, and I said, “Anytime you want to go outside I will kick your fucking ass.” I was very hot under the collar, and I was also in good condition.

But that was a long time ago, and we’ve patched things up; we even worked together on an episode of Hope and Faith. Tony is perennially buoyant, always full of piss and vinegar, and I love that about him. I’ll call Tony up and ask, “Is this Ali Baba?” and he’ll automatically respond, “Prince Valiant?”

Once upon a time, we were young together. Whenever we get together, we still are.

People ask me why I haven’t retired, and sometimes it feels like I have. The truth is, I don’t want to drop dead on a sound stage; I want to drop dead in a river, with a fishing rod in my hand, or in my house in Aspen. There was a period of about ten years when I worked practically every day. My career is important to me, but I’ve learned from therapists like Arthur Malin, Gerald Aronson, and Cheryl O’Neal—as well as my friend and personal physician, Paul Rudnick—that you can only take out of yourself what you put in. It’s ever so important to have life experiences.

That said, I like to work. To appear on a cracking good show like Boston Legal or Two and a Half Men and not have to pull the train is a treat. But the day when I carry a show is over. That said, I’d love to be in an ensemble cast. My professional goal is the same as it was when I was twenty-five: do good work and keep doing it.

In other words, I don’t believe in retirement. I never wanted to sock my money away for a rainy day and spend my eightieth birthday reading the paper. I don’t think building a life around cruises and golf is a healthy mind-set, although I know that a lot of people love it. I think retirement is a hype that has nothing to do with life as it needs to be lived. It’s a collusion between industries that barely existed fifty years ago—life insurance companies and cruise companies—that need to manufacture endeavors in order to sustain themselves. I’ve never bought into it.

Jill has continued to be very influential as a sounding board for my career—guiding and suggesting, never commanding. She’s only put her foot down once. I was asked to do Dancing with the Stars, and I was leaning toward doing it. And she stepped up and said, “I’ve never said anything to you about whether or not to do something. But you shouldn’t do this.” She didn’t think it was the right thing, and I think she was absolutely right. Beyond that, at those times when I’ve been really down and on the bottom, Jill has always been there. You can’t ask for more from any human being. Plus, there is the fact that she’s loving and caring, a wonderful wife, 100 percent for me.

As I said, our experience with Love Letters was entirely positive, but I sweated over it; most nights I would stay up and think about the next performance, because I was doing it for a different person in my mind every night. I knew where the high points were, and I didn’t want it to become rote, which is the great danger in the theater.

Because of the success we had with Love Letters, I’ve had lots of offers to do theater, but I don’t want to work that hard. When my agent calls me with a part, the questions I ask are basic: “What is it? Where is it? How much? For how long?”

I have finally learned that when you work, you work, and when you play, you play. Jill and I have designed our lives so that we can be away together on vacations. It’s a continuation of the rule Natalie and I made when we remarried: the first thing is the family.

I don’t really understand those people who say they wouldn’t change anything about their lives. Hell, I would change a lot of things. Among other things, I lost a woman I loved with all my heart, not once but twice, and that is a truth I will never completely come to terms with. But I have learned through grueling experience that there is no such thing as “what if….” There is only “what is.”

For the rest of it, I would have taken more time in certain ways. I’m not proud of everything I’ve done. There’s no way to get through life without hurting people, whether because of ignorance, or because you think it’s necessary for your own survival, or because you’re just too full of yourself. Those are the moments I regret.

As for Warren Beatty, we run into each other occasionally around town. And when we do, he always puts his arm around me, and I do the same with him. In a sense, we were brought together by the loss of Natalie. Her death was so much bigger than any animus I might have had.

The world of movies and TV has changed, but I’m not going to pontificate about how things were better in my day. Well, maybe just a little. Some things were indeed better then, but some things are better now. Certainly, there’s more independence for young actors now—nobody is trying to marry people off because of inconvenient pregnancies. But that increased independence also means that it’s everybody for himself—there’s no studio watching out for young actors, trying to build a career step by step. The only people with a vested interest in young talent are managers and agents, and there aren’t many who possess a developmental skill set. That’s why many careers are more erratic, not to mention shorter, than they were fifty or sixty years ago. There’s more independence, which equals freedom, but there’s also much greater risk. For everything you get, you have to give something up.

I’m sure the people who were my age now in, say, 1960 thought things were going to hell too. I will say that money has changed things, and not for the better. In the world at large, everything is a corporate commodity. A football game isn’t just a football game; it has to be sponsored by a corporation—Toyota, or AT&T, or Capital One, or, for God’s sake, Tostitos.

In terms of show business, the economics are entirely different as well. A few years ago, I proposed a revival of It Takes a Thief. I would have the Fred Astaire part; I would be running a place in Las Vegas called Mundy’s. Catherine Deneuve would come to see me and tell me that we had had a child years before who was trapped in the Middle East. I would have to go in and get her, and we’d be off into a variation on the original show. It was a good idea, and I think it could have worked, but Universal was practically out of the TV business, because it’s no longer profitable unless you have a big, big hit. Since nobody ever knows what’s going to be a big hit, they had simply edged over to the sidelines.

It used to be that you made a show for a network, they got three runs of each episode, and then the studio owned the show for the rest of the world, for the rest of time. The rule of thumb was that you broke even with the networks and made a profit in syndication. But to make a series today costs $2 million an hour. Twenty-four shows cost $48 million, and there’s no way to recoup that much money unless the show is a success and runs five years’ worth of negative for syndication. It’s not a business Universal is particularly interested in. So I suggested doing six two-hour movies, which didn’t go down. And they wouldn’t let me take the property and do it someplace else, and now they want to do a theatrical version of the property. They might offer me a part, but I doubt I’ll take it.

But let’s face it: the world moves on. Last Christmas I picked up my daughter Courtney to take her to a Christmas party at Natasha’s house. She was on her cell phone to the airlines to check on her airline ticket, then called about a car she had to pick up. Then she needed to stop at an ATM to get some cash. I sat there in the car thinking about my daughter getting money out of a wall and how, right around the corner from the ATM, I had built hot rods as a teenager. It was one of those moments when you realize how much change one life can encompass.

There’s a general perception that show business is far more pervasive than it used to be. Actually, American show business has ruled the world for most of the last one hundred years—Japanese people in the 1930s went to see Charlie Chaplin movies in droves. What has changed is the immersion in show business of people who are not themselves part of it.

Years ago, there was a man named Milton Sperling who produced Marjorie Morningstar for Natalie. Milton decided to take his family to see the most magical place on earth: Venice. He painstakingly prepared his son for the experience he was about to have, and being a producer, he also prepared the experience. He positioned a man with a starter’s pistol way back in St. Mark’s Square. He was to fire the gun when he saw Sperling wave a red handkerchief, so the pigeons would swoop up in a magical swirl at just the right moment.

Sperling brought his boy blindfolded around the corner of the Doge’s Palace and placed him right beside one of the columns at the entrance to the square. Then he waved his red handkerchief, the starter’s pistol was fired, Sperling uncovered his boy’s face, and the pigeons swooped up.

“What do you see, son?” Milton asked proudly.

“I see…Dore Schary!”

A confused Milton Sperling followed his son’s line of vision and saw a smiling Dore Schary passing in front of the boy, blocking out the carefully prepared vista of St. Mark’s Square.

That’s one of my favorite stories because, besides being true, it’s an accurate metaphor. For those of us in it, American show business has always had a way of blotting out the real world. That’s because American show business is cleaner, smoother, and easier to process than the real world, which, unfortunately, is where we actually live. But I’ve learned to have one foot in both camps, and I like to think I’m able to appreciate both the gamesmanship of the movies and a stream full of trout in the Rockies.

If somebody had told me sixty years ago what my life was going to be like and had enumerated the terrible pain I had waiting for me, I would have gone ahead anyway. Because, along with that pain, I’ve experienced great joy, and I’d like to think that I’ve given some as well.

In many respects, I remain pretty much as I was. That little boy who basked at being the center of the photographer’s attention at the preview of The Biscuit Eater became a man who needed attention and could get disappointed if he didn’t get it. In other words, I had the essential personality of the actor—wanting, needing a reaction—before I became an actor. Another character flaw is a plethora of optimism, which can mean I sometimes lack objectivity. In my own defense, I should say that I’ve become more realistic as I’ve grown older.

I look around me and see so many wonderful actors. Johnny Depp is probably the best one working these days—the face of a leading man and the soul of a character actor, which is probably the ideal combination. And I think that Brad Pitt is, for some reason, very underrated. He’s very simple, very basic, and you never catch him acting.

Recently I went out to the Motion Picture Home to visit Helena Sorrell, my first dramatic coach. She’s 104 years old and still pretty sharp. She was in the Audrey Hepburn Room in the hospital, and it was lovely—the sun was coming in, and it was Edie Wasserman’s birthday. Every year, on Edie’s birthday, she goes out to the Motion Picture Home, and everybody there gets wonderful food catered by Alex’s, which has all the recipes from Chasen’s—the chili, the hobo steak, and everything else.

“Do you like it here, Helena?” I asked her.

“No,” she said, “I don’t.”

Helena gave so much to so many people, myself among them, and she ended up alone. So many people end up alone, and for what must be the millionth time, I realized how lucky I’ve been.

No, not just lucky. Blessed. I have a wonderful family and true friends. I never walked away from my own life, like so many people in show business do, and I’ve worked hard, but as I sit looking out over the valley in Aspen, I feel gratitude for my life and think, Am I the luckiest man on earth?

As much as I loved the house in Brentwood, I simply didn’t need seven bedrooms and a cottage anymore, so in 2007 we sold it for an astonishing price. I’m not going to pretend it was easy; Jill and I had been married in the garden, as had Natasha, Katie, and Peter Donen. We had a hundred parties there over the years, and when I looked out over the expanse of lawn and trees, I could see my mother, Jill’s mother, Roddy McDowall, Howard Jeffrey, Peter Donen, Bill Storke, Watson Webb, and dozens of other dear friends who had brightened our lives in that house.

But it was time.

Now Jill and I spend most of our time in Aspen, although we retain a condo in Los Angeles.

My children are all well and happy in their lives, and recently Katie and her husband, Leif Lewis, gave me a spectacular gift: my first grandchild, a boy named Riley John—yet another RJ! I’ve maintained my health and seen and done a lot.

Show business has been my college and my doctoral program. I’ve met queens and kings, seen America and the world. Years ago, Jimmy Stewart got me involved in the Jimmy Stewart Relay Marathon for the Child Care Center at St. John’s Hospital. When Jimmy died, his will made me a founder for the hospital, and my continuing work for them and the John Tracy Clinic has been one of the most rewarding experiences of my life.

For my family, the goal was to go to college, but I rolled the dice and opted to go to work; I like to think that I’ve grabbed hold of life and shaken it. If some of it blew into my eyes, well, that’s called being alive.

When my time comes, I will be buried in Aspen, in an old cemetery that was originally laid out in the nineteenth century. A lot of children are buried there, and it’s in the middle of a glade of aspen and birch trees—very wild and overgrown. As soon as someone is laid to rest, the land is allowed to return to its natural state. The cemetery looks out over the valley, and deer and elk walk through it all the time. Sometimes you’ll notice a large patch of grass crunched down, and you realize that a bear has been sleeping there after dining on the berries that grow wild in the middle of the cemetery. It’s absolutely pure and totally peaceful.

I have four plots in the cemetery, and Jill and my beloved shepherd Larry will be buried with me. And any of the kids who want to be with us. Things change in children’s lives, and I’ll be fine with whatever they decide. It will be a peaceful place for them to come and pay their respects. They won’t have to bring flowers—just some seed, so that the birds and flowers will arrive every spring and enable me to once again be surrounded by life.

I hope that the site enables them to appreciate their father, and, beyond that, reminds them of the beautiful confirmation of life itself.