A group of Inuit set out for a hunting trip in an umiak. These open boats, which might reach 30 feet in length, were useful in hunting whales and walruses.

The Northwestern United States was one of the richest areas on the continent. Natural resources were abundant, and there was always plenty of food to eat. Native Americans filled their bowls with salmon, herring, cod, and halibut. The Chinook people used basket traps and weirs to catch salmon on the lower Columbia River. Fish trapped in a weir were then speared.

The Tsimshian people used rakes and funnel-shaped nets to catch eulachon. Eulachon are small, oily fish. They are sometimes called candlefish, because when dried they can be lit like a candle. In fact, they are so oily that they burn for hours.

The people of the lower Northwest coast were skilled at woodworking. To shape and carve wood, they used axes, chisels, knives, hammers, and wedges. Some tools were made of bone or antler. Others were made of hard stone, such as serpentine or jade.

Northwest men used harpoons to hunt sea mammals. Harpoons are spears with rope attached. The rope lets the hunter pull his prey back to the boat. In 1803, the Nootka people took a big step in harpoon making. Using English guns, the Nootka raided an English ship and stole enough iron to make iron harpoons. This resulted in one of their most successful whale-hunting seasons ever.

A group of Inuit set out for a hunting trip in an umiak. These open boats, which might reach 30 feet in length, were useful in hunting whales and walruses.

As in the Southeast, natives of the lower Northwest coast used dugouts for hunting and travel. Trails in the area were rough and often overgrown with vines, which made overland trips difficult.

The Haida people made the best dugouts in the region. Their dugouts were cut from red cedar trees and waterproofed with asphalt. Asphalt is a sticky mixture of tar, gravel, and sand. Haida dugouts were sometimes 50 feet long and 8 feet wide. They could hold up to 60 men and could carry nearly three tons. The Haida traded their dugouts with many tribes along the coast.

As large as Haida dugouts were, they could be made even larger. Sometimes, Haida men lashed two dugouts together. They would install a plank deck between the boats, making the dugouts into a war ship.

Other tribes did similar things for a peaceful reason. Houses were moved to the ocean shore each spring for herring season. The boards of houses would be lashed to two canoes, making a temporary raft. With the family’s belongings piled on top, the raft was ready to float downriver.

Snowshoes, invented by Native Americans, help distribute a person’s weight over a larger surface and thus prevent the person from sinking into deep snow.

Further north, the dugout gave way to the kayak and umiak. The Tlingit people in Yakutat Bay used both types of boats. Although used for sports today, a kayak is a hunting boat. It is fast and silent, perfect for sneaking up on resting seals. The kayak was also useful in chasing swimming caribou across a river.

By 1860, almost all Native American tribes had guns. Guns were a European invention, and the native people were frightened of them at first. However, it wasn’t long before tribes saw guns as the way to get the upper hand on their rivals.

The English first sold guns to Native Americans in 1670 on the Hudson Bay. The Cree Indians were the first tribe to use guns in battle. They fought the Assiniboines, winning decisively. Then, the two tribes made a partnership. They bought guns from the English and sold them to other tribes. Together, they supplied guns to many of the tribes south and west of them, including the Blackfeet Confederacy.

In the Southeast, Spain, France, and England offered guns to tribes who sided with them against their enemies. In the Northwest, the English lent the Nootka guns so they could attack their neighbors. In 1792, an English trader wrote: “Their former weapons, Bows and Arrows, Spears and Clubs, are now thrown aside and forgotten. At Nootka, everyone had his musket.”

Rifles were even distributed by the U.S. government for buffalo hunting. Still, many tribes used bows and arrows for the hunt. They were quieter and more accurate. However, the gun remained the prized weapon of war. Some warriors even held bullets in their mouths to cut down reloading time.

The kayak was made by stretching sealskin over a frame pieced together with driftwood and antlers. The boat’s pilot would fit into a small hole that pressed tight against his body. This kept water out of the craft. The sealskin was kept waterproof by regularly treating it with animal oils.

The kayak was light enough for one man to carry. This made it perfect for traveling overland as well as through the water. A skilled kayaker could paddle around seven miles per hour, even in rough water.

Unlike the kayak, an umiak is an open boat. Umiaks can be up to 30 feet long and can carry more than a ton of weight. Umiaks were used to hunt whales and walrus—prey that needed a group of men to be subdued. Umiaks are covered in hides. These hides are nearly as tough as wood, but they are more pliable. A wooden boat might break if it hit an ice floe. With the hide covering, there is less chance of serious damage if this happens.

In the frozen Arctic, natural resources are scarce, as it is too cold for trees to grow. The people of this region used every last scrap of what they had to survive. Their only source of wood was driftwood from the south. Arctic tools were made of stone, bone, or driftwood. It didn’t matter what material was best for each tool. When someone needed an axe, he used what was handy to make one.

Like people in other regions, Arctic tribes used bows and arrows. Their bows were antler and driftwood lashed together with sinew. They would be backed with sealskin and braids of caribou sinew for strength. Their arrows were usually tipped with bone.

Dogs pull Mandan sledges across a frozen lake in this 1834 illustration.

Many tools were made from parts of animals. Bone, antler, and tusks were made into sharp tools, like spears, needles, and knives. Inuit women used a moon-shaped knife called an ulu to cut skins and fish.

Skins and hides were important, as was an animal’s oil. Aleuts used lamps filled with oil from sea mammals. They were lit with bird down and dry grass as a wick. Some lamps could be laid flat to warm the person standing above them.

One of the most ingenious hunting tools used in the Arctic was the “death pill.” This was used for hunting wolves. The hunter coiled up some whalebone. Then, he froze the bone into a ball of whale blubber. He would leave it out for wolves to eat. When a wolf ate the ball, the frozen blubber would begin to thaw. When it did, the whalebone sprung open, killing the wolf from inside.

Some umiaks and dugouts had sails of animal hides. It’s not known whether the Native Americans thought of sails themselves or whether they were inspired by English boats they saw.

Another useful hunting tool was a bit of swan’s down. This was useed when hunting seals under a sheet of ice. Seals are mammals, so they need air to breathe. A hunter would hang the down over a seal’s breathing hole. He would watch the down very carefully. When the down moved, it meant the seal was under the hole. Then the hunter would drive his spear through the ice, killing the seal without ever seeing it.

When hunting at sea, hunters used sealskin floats called avatuks. There was usually a rope on either end of the avatuk. During a seal hunt, the avatuk would be tied to the dead seals to keep them from floating away. Avatuks were also tied to harpoon lines during whale hunts and were used as life preservers. An avatuk could keep someone afloat while he patched his kayak.

The Netsilik people on Canada’s Kellet River attracted fish by lowering a lure into the water. A lure could be skin from a salmon’s belly or a piece of bone carved in the shape of a fish. When the fish arrived, the fisherman would slowly raise the lure to the surface. When the fish was in range, he would spear it with a leister.

Due to the freezing climate, overland travel was difficult. Many tribes, including the Tlingits, added spikes to their snowshoes. Modern mountain climbers call these spikes crampons. They make it easier to walk on ice without slipping. Another safety tool was the test staff. This was a stick about the size of a ski pole. It was useful for poking uncertain patches of ice to make sure they could support a person’s weight.

Dogs pulled sleds made of wood or hide with whalebone runners. The runners were supported with crosspieces made from caribou antlers. Strips of rawhide absorbed the shock of bumps in the ice. Some sleds’ runners were made of stiff rawhide. These were coated with a mix of frozen clay and moss. The coating made them last longer and smoothed them out for an easier ride. §

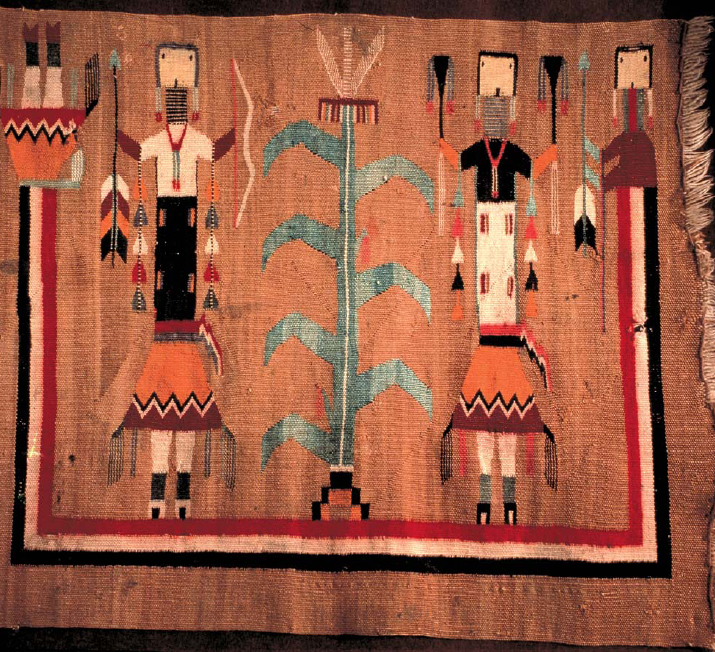

This Navajo blanket depicts two holy spirits with a maize (corn) plant, considered sacred by some peoples of the Southwest.