As you make your way up the Gorge and beyond Vic West, you will come to the municipality of Esquimalt. Esquimalt in the First Nations language means “place of shoaling waters.” This area was once a traditional First Nations village and a rich source of shellfish, most likely because of the shoaling, or shallow, water.

If ever a place had a mistaken image or identity, it is Esquimalt. Of all our neighbourhoods in and around Victoria, Esquimalt is the most surprising because of what one assumes. Esquimalt is home to the Canadian Forces dockyards and naval base. Great yellow cranes in the shipyard can be seen across the water from James Bay and many other neighbourhoods. Part of it, Naden (the name of the base), is accessible to the public and you can take tours by foot or by a shuttle bus. Esquimalt village is simply a stretch of stores that includes two Tim Hortons, a bingo hall, a consignment shop, a small strip mall, a pawn shop (I hear it is one of the best in town), and several pubs and other businesses. But behind the main street and naval base is a wonderful surprise!

There are quaint neighbourhoods of modest little homes with lovely front gardens on quiet streets that lead down to a beautiful park called Saxe Point. It runs along the sea, not overly manicured, but with wild semi-woodland trails full of salmonberry bushes, arbutus trees, and Oregon grape, interspersed with little sandy coves with rowboats tied by frayed yellow ropes to washed-up logs.

Toward Victoria is Macaulay Point, a huge, breezy bluff, dramatic and windswept, with a meadow-like landscape that looks out over the grey-green sea dotted with boats, ferries, and cruise ships. Lovely, neat, cedar split-rail fences guide you along gravel pathways and also protect areas of native plants that the town is trying to encourage.

At the municipal hall you can pick up a thick but neat package of maps and brochures of different strolls and walks through Esquimalt. The pamphlets are wonderfully illustrated with historic photographs, and the map routes are easy to follow. There’s a walk through the Gorge area, the West Bay community (where the houseboats tie up and the mayor has her floating physiotherapy clinic), and other lovely walks that include parks, public art (be sure to see the First Nations mural on the side of the municipal hall), gardens, memorials, footpaths, beaches, heritage and First Nations features, art deco and Tudor revival architecture, and quiet lanes.

One of the most interesting walks is through Old Esquimalt, which begins at the Lampson Street School. The school was originally a four-room brick building built in 1903. The walk through this historic area takes you up through Cairn Park to the highest point in Esquimalt at 232.25 feet. The trail ambles through the Garry oak meadows between great black rock faces and patches of bluebells and fawn lilies. At the top is a stone cairn with a tarnished, circular plaque that points out numerous viewpoints and sites around the region, including First Nations reserves, the shipyards, old railway routes, and elements of the local topography.

The landscapes in and around Victoria offer such a variety of perspectives. Your perspective changes dramatically depending on where you are looking from. Paddling a kayak along the seashore or up the Gorge, riding a bicycle path through a rose garden, and hiking up a rock face offer quite different views—you notice (or miss) different features of the cultural and natural landscape and the people in it, depending on your mode of transportation. But that’s the beauty of Victoria—it begs you to explore all of its neighbourhoods by all means of movement.

On the walk down from Cairn Park you can travel along the “oldest planned road in the west,” Old Esquimalt Road, constructed by sailors in 1852. On this particular walk, the feeling I absorbed seemed much more important than what there was to learn. Sometimes, what you see and learn on a walking tour is not as important as that mysterious ambience you experience just by being surrounded by an area’s features. You can study the information before or after, but if you just walk and observe and enjoy the area, you might find that that is enough. Of all the walking that I do, this area is one of the most memorable, not because of the facts, but because of its feeling.

Saxe Point

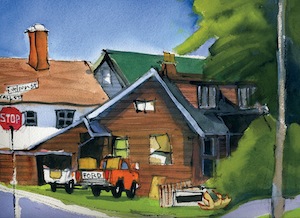

Esquimalt is a place where facts are not as important as feeling and ambience. There’s something about the place that fascinates—those windswept, grassy bluffs and the funny old streets, the railway yards, the little wartime homes, the military hospital up on the hill, the spectacular scenery mixed with the giant yellow cranes in the shipyards, the houseboats and floating homes just down the lane from the Naval Officer Training Centre. It’s a place of contrasts, of rough mixed with smooth, wild with manicured, and tradition with modern, and all with a hint of mystery and the unknown. These are feelings you cannot absorb by reading a pamphlet of historical facts; you just have to wander this neighbourhood and enjoy the diversity.

I have always found military and naval lifestyles (as well as the Sisters and their convent lives) very mysterious and secretive. It seems to be a strangely protected life where one feels taken care of; that’s a nice secure feeling, but at the same time it’s rather odd to be protected by such structure and routine.

You might never think it, but the navy and the Sisters have a lot in common. They both practise an intense discipline, usually behind closed doors; they both wear rather curious outfits (most nuns don’t actually still wear habits); they both rely enormously on teamwork; they both hold a great deal of faith; they are both gender based; and they both, I would expect, are a challenge to enter and a challenge to leave—opposite sides of the same coin! But it’s that mysterious life they both lead that is so intriguing. They seem more secretive than a spy or a private investigator because they are more visible within society than spies but you still don’t truly know what they do in their worlds.

Part of the naval base is accessible to the public but much is private. You go through the great red-brick gates at Naden and up on your left is the store—they have their own store ! You can buy everything from a waterproof notepad to big boxer shorts to raspberry candies. They have their own gym and skating rink, and there’s even a little sailing school down the hill at the back of an old building in a gritty parking lot. Naden has a wonderful band too. I never stopped to think about how valuable a band is to the military, but it is, not only for ceremonial purposes, but for the mood of the military, especially during conflict—it’s moving to think of the band playing in the midst of a horrific war. The band is also a link between the outside world and the gated world of the military; the musicians act as ambassadors to their military bases, connecting in a small way from our lives to theirs.

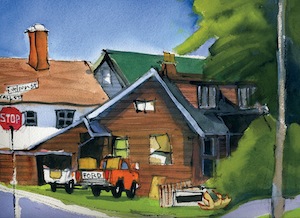

Esquimalt Municipal Hall

The dockyard is off-limits to us, but you can drive or stroll throughout the Naden base, which is a twisting array of little roads, red-brick heritage buildings, and pockets of grassy knolls and shrubbery including a huge, blazing-red rhododendron in front of the library. It’s a strange little community. I cannot pinpoint exactly why I find it so intriguing, but it is; there’s an air of mystery about the place, a mystery combined with an order amongst all this history, with a dark submarine just down the hill, snug against the dock in the off-limits area (probably being repaired) and our grey frigates anchored out in the harbour mist.

The military museum on the base is excellent. It is housed in an old brick building with white trim, yellowed windows, and white columns along a veranda or porch—it looks like something from the Deep South. Heavy bronze radiators heat the musty, carpeted hallway and dim rooms, which are light blue with white wainscoting. There are all sorts of naval memorabilia and displays. In the dark, cave-like Communications Room is a worn poster with red lettering of OFFICIAL SECRETS; there is a photograph of Mollie Entwistle receiving a medal for her “conspicuous coolness and courage” in rescuing people from a fire in the mess hall; there are displays of intricate knots including the “Granny Bend” and the “Single Marriage Bend”; there is a muster kit and the list, in alphabetical order, of supplies a soldier could sign out. Under H is “house wife!” I asked a passing sergeant if this was a joke and he chuckled and said, “Well, let’s put it like this. If the army wanted you to have a wife, they would have issued you one.”

There is a ditty box, a small wooden box for the soldiers to keep their personal treasures in (everyone should have a ditty box, a little secret piece of privacy); an old rusted ration kit that includes a little package of biscuits and a Bible; and, in a battered wooden frame hanging on the wall, a photograph of our first Canadian First Nations woman to sign up, Private Mary Grey Eyes from Saskatchewan.

In another room was a travelling exhibit on naval mascots—animals! There were wonderful photographs of men in their white sailor suits scrubbing the decks with a little white goat keeping watch, or a big cat lying in its own hammock with one leg hanging over the edge. One boat even had a dexterous bear cub who liked to sit on the bow, and there were Gus the goose, dogs, and a parrot too. Cats were especially popular, though, because they kept the rat population in check—rats chewed many a rope in the bowels of the ships.

Before leaving this charming museum (many other rooms were crammed with toy soldiers, brass bells, photographs of admirals, artifacts, land-mine maps, and rum bottles with labels from Waterloo, Ontario), I signed the guest book in the hallway and picked up a few free brochures on the navy’s history. I also picked up a gold and red pin that honours our Canadian soldiers, who not only go to war but are peacekeepers as well. How I wish Canada was more of a peacekeeper! I feel so proud of Canada for our kindness and modesty in the world, but my pride would double if we were still known as peacekeepers—I really think that peacekeeping is one of the noblest actions a country can take on. The pin is on my jacket, next to the art-gallery pin of the Shinto shrine.

As I left I took one more glance at a 1940s poster that encouraged women to sign up; it promised a great life, with good food, recreation facilities, friendship, and a future. Mum signed up and was a war artist—she says it was one of the greatest times of her life.

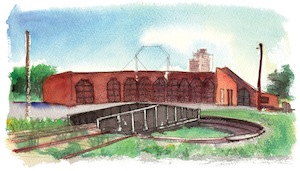

E&N Railway Roundhouse