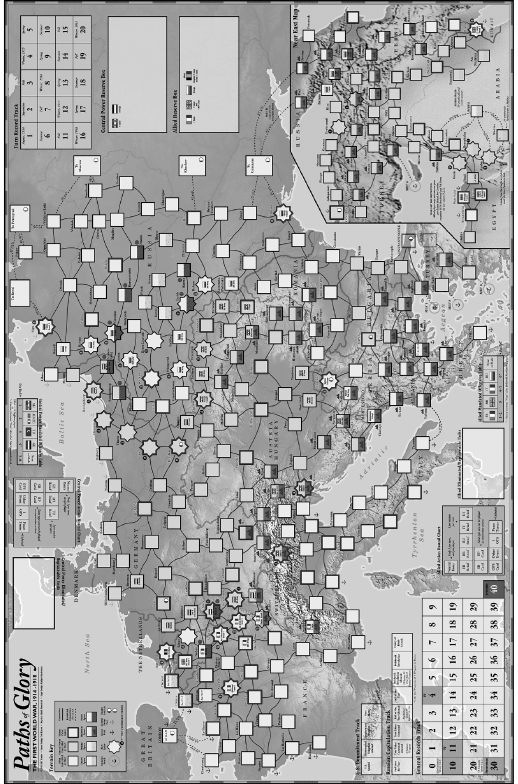

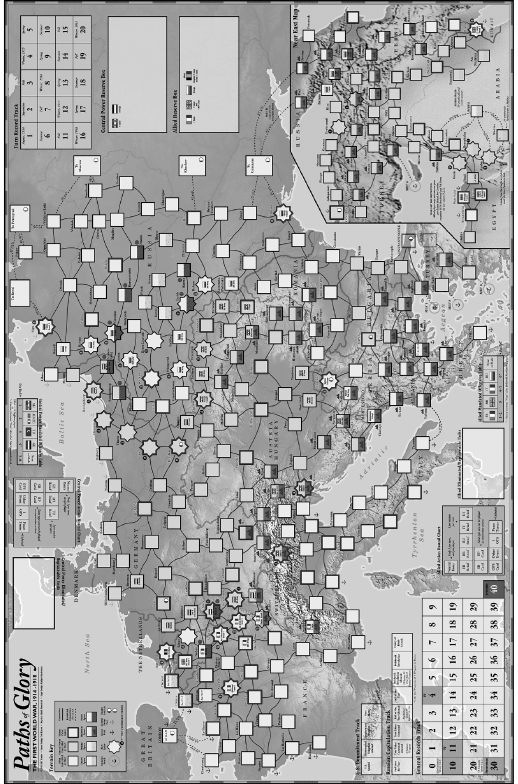

Figure 13.1 Paths of Glory map, showing Europe and Near East insert.

The year 2014 marks the centenary of the outbreak of the First World War (known until 1939 as the Great War), a conflict now little known to the general public but widely understood by historians to be the foundation of our world today. Even a partial list of the consequences of World War I is staggering: the Russian Revolution and the rise of Communism, the emergence of the United States as a world power, the rise of fascism, Nazism, and Japanese militarism, World War II, the Cold War, the fall of Europe’s vast colonial empires.

But despite its historical importance, World War I gaming was mostly relegated to the fringes of the commercial wargame hobby during its first Golden Age (the 1970s and ’80s). Apart from David Isby at SPI, no designer specialized in Great War games, and many of the games produced dealt with air or naval combat, despite the fact that World War I was overwhelmingly a land war. Even by the mid-1970s, with scores if not hundreds of games in print, you could count the number of World War I land games on your fingers, with digits to spare. This situation remained largely unchanged into the 1990s, at which point my own designs helped spark a new interest (one could hardly say “revival” of interest) in the subject.

One reason for the lack of popularity of World War I games into the 1990s was simply that most designs (Isby’s excepted) were not very good. (“World War I games don’t sell,” I was told by Avalon Hill when I tried to sell them my first design. To which I wanted to reply, “Well, not the ones you’ve published, anyway.”) But the real underlying cause of the gaming public’s lack of interest was the myth of the Great War as a static struggle in the trenches, which reduced a conflict of tremendous geographic scope and military variety to the stalemate of the Western Front in 1915–17. The five World War I games I published in Command magazine from 1992 on helped break that stereotype, and by the time the decade ended the war was, if not a hot topic for wargames, at least a warm one.

Nevertheless, the popularity of my last design of that decade took everyone, including me, by surprise. Published by GMT Games in 1999, Paths of Glory: The First World War, 1914–1918 (known to most gamers simply as PoG) was an instant hit, swept every available hobby award, and has been reprinted three times (a fourth reprint is in the works). It has been published in French, German, Spanish, and Chinese versions and has a website in Polish dedicated to it. Nowadays it is even linked to from most websites talking about Stanley Kubrick’s classic movie Paths of Glory. In the relatively small pond of the wargame hobby, it turned out to be a monster fish. Why?

Credit in the first instance must go to game designer Mark Herman, who allowed me to borrow the idea of a card-driven wargame (now known in the hobby as CDGs) from his game We the People (1994), which was both about the Revolutionary War and revolutionary in its design. We the People gave its opposing British and American players a hand of randomly drawn cards. Some of these were used to conduct military or political operations on the point-to-point map board, while others contained historical events (the Declaration of Independence, French intervention, Indian massacre, and so on) that affected the course of the war. The CDG system accomplished multiple design goals in a simple, elegant fashion. As in any card game, having a hand of cards allowed for a certain level of advance planning, while lack of knowledge of the opponent’s hand introduced an element of fog of war, and the random nature of the draw Clausewitz’s “friction” (“In war everything is simple, but the simple things are difficult”). The use of the cards for events allowed the game to cover a broad range of political, economic, diplomatic, and other factors that are often completely abstracted out with minimal rules overhead.

My initial reaction to this amazing design was that it would work very well for an American Civil War game, but it turned out Mark had already had the same thought, so as someone already known for World War I games, I decided to consider whether I could adapt the CDG system for the Great War.

The challenges were considerable: We the People was designed for a war between two nations (with help from a third) using small armies that engaged in nonlinear campaigns, in which your entire force on the map might be concentrated in a couple of spaces, and the action revolved around whether to move from, say, New York to Philadelphia or Boston. The Great War involved five great powers (and two minor powers) from the start, with others entering later. Millions of men were mobilized—several times the entire population of the thirteen colonies in the Revolutionary War—and the opening campaigns involved lines of armies moving together over hundreds of miles of front. A straight adoption of Mark’s system was clearly not going to work, but I was determined to use as much of it as I could, if only because a Great War CDG promised to be a hard sell, and the We the People system an obvious selling point. (At the time I assumed We the People was a big hit for Avalon Hill because I enjoyed it so much; I’m no longer sure if that was actually the case.)

So, for starters, in addition to the use of cards, a point-to-point map gave We the People players a familiar entry point into PoG. The basis of any wargame is its representation of military formations and terrain. A wargame map is inherently abstract: Your map is your game board, like the 8 × 8 square in chess, and once you place any sort of grid over a map to regulate the movement of your military units you are faced with choices that involve abstracting geographic reality. You are deciding what terrain was militarily significant at your chosen scale and how to depict it in the context of your design’s rules. But there is no question that a point-to-point system involves more abstraction, and more designer choices, than a traditional hex grid.

This was complicated by my desire to include the Near East theater (Egypt, Palestine, the Caucasus, Iraq) as well as covering the entire European theater from Paris to Minsk and Riga to Salonika, all on a single standard 34″ × 24″ map. This would require either increasing the scale of the European theater to present a very limited number of spaces or doing the Near East map at a different scale. I chose the latter because I wanted to model operations in France and Russia with sufficient detail to give a sense of the almost-Napoleonic maneuvers attempted by both coalitions in 1914. The limited logistical capabilities of the Near East theater allowed me to narrow the lines of movement so that a few well-chosen chokepoints could stall an enemy advance, making up for the fact that the larger scale meant units were actually marching a greater distance when moved.

Figure 13.1 Paths of Glory map, showing Europe and Near East insert.

Despite the inherent abstractness of a point-to-point system, the PoG map actually contains a fair amount of detail: swamps, mountains, forests, deserts, and man-made fortifications. Each space was named, but because each space covers a much bigger area than a single city or town, the specific names were chosen for historical flavor, not precision. Setting the exact arrangement of the map spaces was largely a matter of trying to model, at the strategic level, the major campaigns of the war. For example, to re-create the actions of the German First Army in 1914, I had to draw map connections that would allow it to destroy the Belgian forts at Liège, force a retreat of the British Expeditionary Force from Belgium, then advance through Cambrai and Amiens. At that point, in order to stay in touch with the rest of the German line, the First Army turned inward (southeast) to the Marne, and then when the Allies counterattacked in September, it retreated to the Cambrai space, where it entrenched. Later in the war, the ability to attack the Cambrai space from multiple spaces can encourage Allied assaults (the Somme) just as the similar vulnerability of the Verdun space makes it a likely target of German attacks. All of this involved a lot of trial and error through playtesting.

PoG was not my first strategic World War I design. I had already published The Great War in Europe and The Great War in the Near East in Command magazine, which could be combined into a campaign covering the same theaters of war as PoG, but with a traditional hex-based system and on a very different scale: three maps instead of one, and divisions instead of PoG’s armies and corps. These earlier games used a random chit draw system to introduce various historical events into play, and I adapted many of these into the events in PoG’s cards. Since practical cost considerations limited me to a deck of 110 cards, it was clear I could not include all the events I wished to if I followed We the People’s course of separating out cards allowing operations from those providing events. It would also be fatal in the linear campaigns of World War I for a player to be stuck with several event cards and unable to respond as enemy operations broke open his front. But once I decided on dual-use cards, where each one would allow either operations on the map or an event (but not both on the same play), I quickly decided to take things even further, and added two additional options for a single card play: strategic movement and replacements. The former would allow a player to move units long distances by rail or by sea, and the latter would allow the player to “call up” troops to replace losses as needed.

Because each card can usually only be used for one purpose each card play (or “round”) the player would constantly have to prioritize. Perform operations on the map or use an event to bring in reinforcements or provide a special tactical advantage, such as poison gas? Move units from front to front by rail, or call up replacements for your worn-out armies? This tension was intensified by having the play of most events remove that card from the game, and by having the most useful events provide the highest level of operations, strategic movement, and replacements. Trade-offs, always trade-offs, and the sheer number of choices ratcheted up the tension to levels some players actually found headache-inducing!

In We the People (and his subsequent CDGs), Mark Herman has favored a single deck. This has some advantages, particularly regarding the element of surprise and the reduction of card counting and deck management, but it has the flaw of increased randomness—a lack of narrative coherence. The events of the war tumble out unconnected from each other and create a game narrative in which the different distinct periods of a typical conflict blur together. Instead, in PoG (and my subsequent CDGs) I chose to give the Central Powers and the Allies their own card decks, and then divided those into three periods: Mobilization, Limited War, and Total War. This prevented the Germans from randomly developing the shock troop (Stosstruppen) tactics of 1917–18 in the early days of the war, since those cards are in the Total War deck.

I then tied the player’s use of his later Limited War and Total War cards to the increase in his War Status, itself raised by the play of certain events. For example, the Allied Mobilization Deck Blockade card not only provided a victory point to the Allies each year but also increased the Allied War Status. And the combined War Status of the two sides, marking the war’s growing intensity, was tied to the play of cards bringing in the United States and threatening Tsarist Russia with revolution and withdrawal.

I now had the game’s CDG engine in working condition, but how to integrate it with the varied and changing nature of actual World War I land campaigns? In We the People, Operations Points (OPS) had been played to activate leaders (generals) on the board and the forces stacked with them. The better the leader, the fewer OPS points were required. Such a system would be out of place given the vastly larger armies, linear fronts, and frankly generally mediocre generalship of World War I. Instead, each OPS point would be allowed to activate a single space, so that depending on the card played, one to five spaces could be activated. This would allow for a historical level of activity and coordination, while ensuring a player could never do everything at once.

I had insisted for years that World War I was not just the trench stalemate of western memory, but, of course, it did include that trench stalemate. The actual movement and combat system would have to allow for both mobile operations and deadlock. So first, to slow the action down to levels that fit World War I and not the blitzkrieg of World War II, I separated out Movement and Combat as types of activity. When you activated a space through OPS points you marked it for Move or Combat, not both. The attacker was now only able to strike at a target space he had moved adjacent to in a previous round, and this gave the other side warning of where a blow might fall, and so a chance either to reinforce it or to withdraw first. To this I added card events allowing the construction of trenches, which gave the defender the option of ignoring retreat results in combat at the cost of additional troop loss. But I made entrenching a particular space a matter of a die roll, giving the French, British, and Germans a greater ability to dig in than the Russians and Austrians—which, along with the shorter front line in France/Belgium, makes a trench stalemate far more likely in the west than the east.

Next I had to deal with the matter of supply. On the strategic level the ability of the various powers to raise and maintain armies was dealt with through the play of reinforcement event cards, and the use of cards for replacements. Battlefield supply was another matter. The traditional “trace through friendly hexes (spaces) to a supply source” was fine, but raised the question of what the penalty would be for an army caught out of supply. Controversially, I decided to make the penalty drastic indeed: an inability to perform operations, and permanent elimination if still out of supply at the end of a game turn. But this drastic penalty had the desired effect: As with their historic counterparts, the players became paranoid about open flanks and breaches in their lines, and would shut down all other activity to protect their lines of supply. This prevented the game from producing a series of encirclements and pocket battles which would be more 1939–41 than 1914–18. Among experienced players, checking supply first each round became second nature, and in practice few units are actually lost to attrition.

Finally, I faced the question: What constituted victory in World War I? From early on in the war both coalitions expanded their ambitions, until they eventually required the complete defeat of their opponents to meet their goals. But apart from marching into Paris, Berlin, or Vienna, no one had any idea of what it would take to force an enemy surrender. Instead, battles were fought to secure ground for tactical, operational, or strategic reasons, or because annexing that ground was part of a nation’s war aims. So I decided on a victory point system based on the control of certain spaces, but affected by the play of certain card events, which would raise or a lower a nation’s morale, and thus affect what it was willing to accept to “win.”

The combination of all these design elements, using a relatively simple set of rules thanks to the CDG engine, produced extremely complex effects. Despite months of testing, with six choices of card play per side per turn and the need to balance events, War Status, replacements, and actual campaigning, there was every possibility that PoG would collapse once it was released into the hands of thousands of players. But though there were problems (for example, the rules for the Allied invasion of Gallipoli had to be altered to lower Allied chances to more historical levels) the game held up, and became my most successful design.

In today’s market, where scores of wargames are released every year, it is a mark of PoG’s success that some gamers have played it enough to develop an expertise far beyond that of the designer. In fact, over the years these “PoG sharks” forced me to respond to their play, as they developed rather ahistorical strategies for winning, chief among them withdrawing German forces to the Rhine and focusing their campaigns on Italy and the Near East. While this was not historically impossible, it was certainly improbable, and I introduced a “historical variant” to the game that I believe solved most of these issues. The sharks themselves went further, and have over the years designed and refined a tournament version. Many players, less experienced and perhaps cutthroat, still prefer the original, more open version of the game, and as a designer one always has to remember that the game must work for the far larger number of casual players and not the sharks alone.1

After PoG was published, interest in World War I gaming continued to grow. I published several more Great War designs and was joined by a range of other designers, producing games of both monster size and complexity and pocket games playable in an hour or two. World War I will likely never be as popular a game topic as its bigger child, World War II, but it is no longer a neglected corner of the wargame hobby. PoG has helped people understand that the Great War consisted of much more than stalemate in the trenches, and in many cases it has led players to a deeper exploration of the history behind the game. In this way, PoG has played at least a small part in the increased interest in the conflict one hundred years on. “The paths of glory lead but to the grave.” Or, sometimes, to the gaming table.

Ted Raicer was born in 1958 to parents who served in World War II. Raised in Rahway, New Jersey, he took an early interest in military history through studying the Civil War, and his love of English literature later led to a broad interest in European history, particularly the two World Wars. His father bought him his first wargame in 1969 (Avalon Hill’s 1914), and by the mid-1970s he was a dedicated hobbyist. In 1991 he published his first game, 1918: Storm in the West, for the late lamented Command magazine. A string of award-winning World War I games in Command followed before the publication of his most famous design, Paths of Glory, by GMT Games in 1999. PoG, as it is generally known, has been through three additional printings, with another on the way, and has been published in French, German, Spanish, and Chinese editions.