Thousands of Americans, usually men, belong to gaming communities that play out historical battles with miniature soldiers on handmade dioramas, a hobby that began in the mid-1950s, at the time of the Cold War. Gamers may stage the battles of Hittites and Babylonians, the Napoleonic Wars, or World War II, beginning from historically accurate circumstances and representing both sides in the given conflict. Their games are not reenactments, however, because events proceed not only according to the demands of military strategy but via rolls of the dice. Play thus yields ahistorical, counterfactual outcomes.

This activity could be seen as an exploration of alternative realities, possible worlds. Yet historical wargamers take great pains to establish realistic conditions for their play. By assigning values to particular dice throws, the gaming rulebook accounts for variables in ballistics, terrain, weather conditions, fatigue, injury, and so on, a blending of computation and happenstance that speaks to the intensely technical yet profoundly random conditions of battle. Deeply psychological phenomena also take hold in the midst of game play, just as they would in actually life-threatening circumstances. Indeed, gamers report that they enter a “magic circle” in which the diorama comes alive with all the stress, elation, calculation, exhaustion, and uncertainty of combat. Needless to say, however, when the game is over, no injuries have been sustained, and no world-historical balance of power has been shifted.

At the moment of this writing, in September 2014, the US military has pulled out of Iraq except for personnel staffing and guarding the embassy in Baghdad. President Nouri al-Malaki has spent years alienating its Sunni majority. The Sunni insurgent group ISIS is hoping to establish a new caliphate, and to that end it has captured the city of Mosul, taken towns along the Tigris and Euphrates rivers, and surrounded Baghdad. All this presents yet another kind of “possible world”—a reality not envisioned in the 1997 Statement of Principles generated by the Project for a New American Century (PNAC), which, well in advance of the 9/11 attacks, argued for the strategic importance of invading Iraq. Several authors of this document, including Donald Rumsfeld and Paul Wolfowitz, later found themselves in positions from which they could help to implement—in real time, with real combatants, in real places—the hypotheses that had been generated years before under think-tank conditions.

Figure 34.2 Miniature War in Iraq (Dice Throw) (2007), video still.

The use of models, maquettes, and game boards in formulating military maneuvers and training soldiers goes back to early forms of chess and perhaps to ancient times; tabletop wargamers’ play and elite geostrategic planning exhibit significant structural similarities derived from their shared historical sources. Inevitably, such modeling circumscribes and distances the messy, contingent facts of full-scale political and/or armed struggle. The map is not the territory, and, after all, any form of representation foregrounds some aspects of reality while bracketing others. Still, relations between processes of strategic modeling, gaming, and propaganda should not be overlooked. As consumers of news in globalized culture, and as citizens taking part in the American electoral system, we depend on media sources that are increasingly corporatized, expensive to sustain, and restricted in their support for in-depth investigative reporting—in other words, our information sources are, like wargames, distanced, filtered, and allied to entertainment formats. Yet our political choices can only be as grounded as our news is “factual” and “real.”

Military planning, politics, and media are not alone, moreover, in their reliance on gaming structures. Other disciplines have their own discourses of the counterfactual. In psychology, counterfactual thinking can lead, on one hand, to obsession over missed opportunities; on the other, it serves an important function in teaching patients to self-correct maladaptive behavior. In epidemiology and other health sciences concerned with disease control, researchers seek to predict the spread of illnesses under diverse potential conditions. Analytic philosophy discusses the truth-value of counterfactual statements and the use of modal logics in relation to possible worlds. As an artist with a background in all three of these areas of study (I earned a bachelor’s degree in psychology and studied the philosophy of science before getting a PhD in analytic philosophy), speculation about diverse epistemological structures and the ways in which knowledge is established and given transitive form have remained among my primary interests. Art is distinct from social science and philosophy in that it privileges “uselessness” and sensuality for their own sake, and I was drawn to make art in part because I value its ability to realize possible worlds in physical, deliberately crafted objects, to make irrational postulates visible and sensually appealing. Art embraces its own falsity and nonconsequentiality, foregrounding nonrational thought and demarcating free-play zones.

Figure 34.3 Miniature War in Iraq (Confrontation) (2007), video still.

It is with such ideas in mind that I developed a project titled Miniature War in Iraq (2007), along with a second iteration titled Miniature War in Iraq … and Now Afghanistan (2010). Part game and part thought experiment, encompassing performance, sculpture, video, and photography, Miniature War investigates what might be called interlocking “magic circles,” discursive spaces in which, at times, we lose our bearings in the seductive intensity of our involvement. Artistic practice neither denies nor apologizes for the status of its objects as unreal. Yet despite its fascination with vicarious experience, Miniature War was not entirely unreal either. An uncomfortable connection to real violence was self-consciously built in to the project through the melding of current events in Iraq with gameplay in the United States, and the incorporation in the installation of streaming online footage from the conflict, as well as via the participation of Middle Eastern researchers who, during the performance, were communicating live with individuals in Iraq.

Miniature War in Iraq took shape in the following way: at Games Expo in Las Vegas in March 2007, I collaborated with a group from the Kansas City–based Heart of America Historical Miniature Gaming Society to play/fight recent battles from the war. An onsite Arabic-speaking research team that had traveled with me to Las Vegas investigated competing versions of events then unfolding on the ground, culling information from the New York Times and Al Jazeera, militant Islamic websites, US military sources, American soldiers’ selfies and combat videos, and real-time exchanges with Iraqi bloggers. The researchers selected an event to be played, and handed off that scenario to the gamers. Guided by resources such as Google Maps, and using their standard kit of materials—which includes model buildings and trees, toy cars and trucks, sand, and other props, as well as mass-produced cast-metal soldier-and-civilian figurines, many of which are designed for use in scenarios from the Crusades—the gamers proceeded to build a tabletop diorama representing the setting of the selected events. For the first day of play, the scene was a village and date-palm grove in the Zarga region near Najaf. On the second day, the diorama was reconfigured to become a Baghdad neighborhood.

The 2010 performance, Miniature War in Iraq … and Now Afghanistan, occurred in New York City. The engagement in Afghanistan has been the longest war in US history. President George W. Bush launched Operation Enduring Freedom against the Taliban in the first week of October 2001. Two years later, for reasons consonant with the PNAC plan, American forces were diverted from their focus on the Taliban and Al Qaeda by the occupation of Iraq. I was prompted to produce my project’s second iteration when, nearly a decade into the quagmire, the newly elected Barack Obama sent thirty thousand additional troops to Afghanistan. The surge resulted in the war’s deadliest single year—and, in the present, the country remains unstable.

Figure 34.4 Miniature War in Afghanistan (Crossing) (2010), performance.

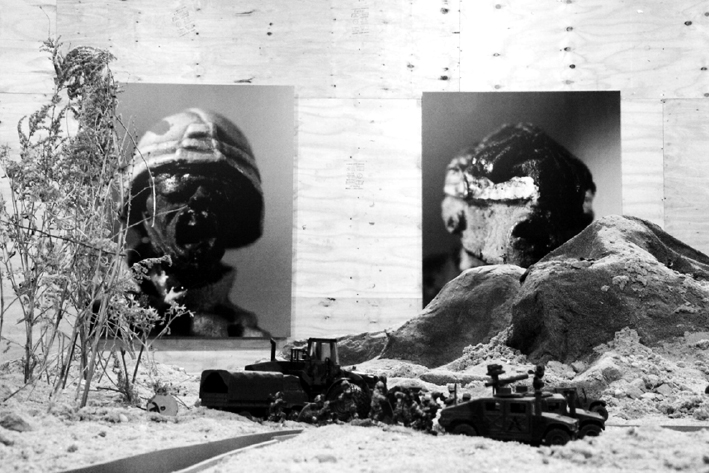

Miniature War as it opened in New York was an installation comprising the game table as it had been left at the close of the final Las Vegas game, along with a video documenting the 2007 game in play, plus an array of Web-based and hardcopy materials gathered by the Arabic-speaking research team, whose computers—monitors still screening the online footage culled in 2007—sat at the edge of the tabletop diorama. On the walls hung photographic portraits of several of the mini soldier figures, heroically enlarged to a scale at which imperfections in casting and painting loomed grotesquely. One month later, toward the end of the New York exhibition’s run, the diorama was reorganized, and a game master from the Heart of America society joined with visitors to the gallery and local artists to play a new, Afghanistan-based game. Working live alongside the players, Pashto- and Dari-speaking researchers selected and documented a scenario from then-recent events in Kandahar.

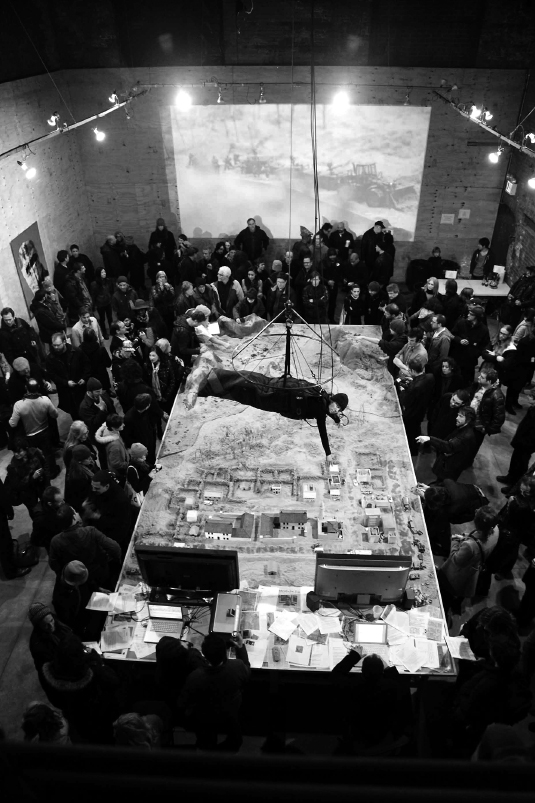

For this performance, the table itself was also reconstructed. While American and Iraqi combatants in the 2007 game were relatively equal in their ballistic and logistical capacities, each side in the 2010 game had distinct powers and deficits. Because the diorama was so large, any given player could only reach a third of the way toward its center. But the table had been cut into four puzzle-like parts and placed on wheels, so that each section could be positioned independently. Only Taliban players were allowed to pull the table open to move soldiers and materiel in the interior. The Americans, however, could overfly the entire scene: A performer (as it happened, a young woman) was suspended in a harness above the table, holding a model drone in one hand and with the other controlling an electronic joystick that allowed her to cruise back and forth above the diorama.

Figure 34.5 Miniature War in Afghanistan (Toy Soldier) (2010), color photograph mounted on aluminum.

Historical gamers approach and retreat, at one and the same time, from the violent situations that absorb them; they enjoy the visceral drama of battle but their games are by definition limited, pretend. In order to do their jobs, meanwhile, military planners must believe that by playing out their hypotheses via projections and metrics they will be able to predict the consequences of various battle plans. They are confident that their modeling and framing will deliver actualities on the ground. When online communities coalesce around a particular multiplayer game—or when friends devote hours to a first-person-shooter game—a mood takes hold that blends intimate enmeshment and consequence-free distance, engagement and detachment, in not unrelated ways. Such psychological effects can also be experienced by a viewer who is not playing the game, yet participates vicariously—as do noncombatant partisans in any conflict, as well as spectators watching other kinds of games. Not least among these uneasy meldings of approach and retreat is drone warfare, in which a specialist in Nevada, say, may be engaged in remote-bombing a target in Tora Bora—a (partial) dephysicalization of deadly force that, in many ways, functions in synergy with the apparatus of highly aestheticized computer games designed for entertainment.

Nevertheless, there is also a difference between virtual and analog wargaming. In three-dimensional analog games, the manipulation of objects in real time is paramount—as against the virtual feats that a videogame avatar, or a drone operator, can accomplish. Players roll the dice and move the playing pieces by hand; they reach across the table, crane their necks for sightlines, crouch to measure distances, and so forth, yet all the while they tower gigantically above the fray. This tension is emphasized in the Miniature War video of the 2007 game in play, where all we see are the godlike hands of players reaching in from out of frame to gather up or knock over figures, upend vehicles, or dismantle buildings. The magic circle of absorptive involvement is made tangible in Miniature War, even as it is exaggerated to an extreme, almost caricatural level.

Figure 34.6 Miniature War in Afghanistan (Drone) (2010); performance.

If this video draws attention to the fantasies of deus-ex-machina mastery inherent in both miniaturization and military planning, other parts of the installation seek to dramatize other aspects of the information system that surrounds us. The online research teams used sources of all kinds, from the US State Department or the Washington Post to insurgents’ video posts. Is such official or eyewitness documentation more real than the three-dimensional, vividly detailed diorama or the monumental photographs—which suggest a cross between billboard advertisements and posters eulogizing fighters as martyrs? Are screengrabs from the Internet or data retrieved from wire service reports more real than the physically immediate actions of the players, or the excited responses of the gallery audience? Perhaps. But in what ways, exactly? And where, in all this speculation, is the reality of individual people shot at, bombed, burned, maimed, suffering from PTSD or haunted by memory? These are questions that Miniature War hopes to provoke.

Propaganda is a magic-circle machine, but its goal is to entice audiences to suspend disbelief, to accept the exaggerated or counterfactual as real. Art, in contrast, constantly reminds the viewer that representation, information-relay, even “truth” are inextricably bound up with projection, theatricality, and all the shifting formulas of “as if.” Art insists on its identity as a game. At the same time, because Miniature War intersects with events that have had literally bloody consequences, the project also seeks to expose our understanding of faraway war as inescapably partial and therefore degraded.

But the magic circle is not only a space where misinformation and projection can hold sway. It is also a zone of imaginative empathy. In a game about World War II, one group of participants might have to play as Nazis; in a scenario derived from Vietnam, some players would have to fight as Viet Cong. When players take on these “enemy” roles, they plunge in with full conviction, urgently feeling what it is like to be something, or someone, that they themselves probably abhor. In the same way, in Miniature War, some gamers were required to play as Iraqi insurgents, Taliban fighters, or al-Qaeda operatives and to strive wholeheartedly to win the day—which they did. I would argue that this relinquishing of identity on the part of the player, which the viewer witnesses and in which he or she vicariously takes part, holds an important potential for opening up an imaginative frame of reference beyond the game itself. In this sense, there is no righteous position from which to play the game. Art freely admits its power as a magic-circle generator, and this means, I believe, that art can reflect in unique ways on even such dire and tragic human events as war. Using a set of conceptual tools not available to journalists or academics, art can cast the spell of the counterfactual while still insisting on the immediate.

Brian Conley’s practice as an artist encompasses multiple media, from radio performance to sculptural, research-based, and collaborative installations and is concerned with the roots of social violence, the origins of language, and the possibility of meaningful communication even across radical divides—for example, between human and animal. He cofounded Cabinet magazine and participated in the startup of a remote-teaching art program and communication hub for Iraqi artists in the diaspora as well as those in Baghdad. He has exhibited internationally, including at the Whitney Museum of American Art, ArtBasel, and MassMoCA, as well as producing commissioned works at the Wanas Foundation in Knislinge, Sweden, and the ArtPace Foundation for Contemporary Art in San Antonio, Texas. Conley holds a PhD in philosophy and an MFA in studio art from the University of Minnesota. He is a professor and acting chair of the Sculpture Program at the California College of the Arts in San Francisco.