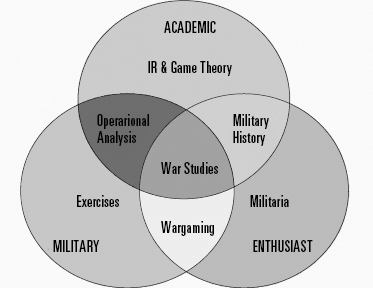

Figure 35.1 Techniques used by different groups to study armed conflict.

I have been an academic in the Department of War Studies at King’s College London for thirty years, and an increasing focus of mine during that long period has been designing and using wargames as an instrument of education and research. Simulation and gaming are very much growth areas in higher education as a whole, and there is an increasing literature about their utility to engage students in an interactive learning process (Crookall and Thorngate 2009; Kebritchi and Hirumi 2008; Lean et al. 2006; Moizer et al. 2009). There have even been entire recent special issues of the journal Simulation & Gaming devoted to the use of such techniques in the specific academic field of international studies (Boyer 2011; Brynen and Milante 2013). Rex Brynen and other scholarly contributors to this volume give a good sense of the popularity of such exercises, even when they reach such heights of ambition as Rex’s own very intensive weeklong peacebuilding simulation involving over one hundred students (Brynen 2010). Where my own experience differs is that I focus not on the widely used and easily understood techniques of “pol-mil” gaming, with its emphasis on negotiations, role-playing, and seminar discussions, but instead on much more structured models of actual armed conflict, more akin to the various recreational wargames discussed in many chapters of this book.

Academics are certainly no strangers to formal models that try to capture the dynamics of real conflicts within numbers and formulas. Operational analysis and mathematical modeling are flourishing academic fields, and “game theorists” have long tried to analyze human decisions with reference to simpler analogical situations such as the “prisoner’s dilemma” (Biddle 2004; Haldon et al. 2010; Shubik 2002; Morse and Kimball 1959; Schelling 1960). However, wargames of the kind discussed in this chapter fall uncomfortably in between these rigorous and rather arcane mathematical models and the much freer and less structured role-playing in international studies classes. Apart from the many sociological studies of the impact of violent video games (e.g., Anderson, Gentile, and Buckley 2007), and the occasional rather plaintive article urging the use of hobby wargames in history teaching (Glick and Charters 1983; Corbeil 2011), one would scarcely know from the scholarly literature that wargaming of this kind even existed.

As the Venn diagram in figure 35.1 makes clear, wargames are designed and played much less by academics than by two other groups, without which they would not exist at all. The first group consists of the many private enthusiasts who for over half a century have seen wargames as an intriguing supplement to books and films as a safe vicarious means of exploring the dynamics of armed conflict. The specific wargames discussed in this book are only a tiny fraction of more than ten thousand different hobby game designs, played with computers, cardboard counters, or model figures, and covering between them almost every recorded conflict in military history (Sabin 2002; Halter 2006; Dunnigan 1992b; Martin 2001; Lewin 2012; Hyde 2013). The other key group that has underpinned the development of modern wargaming techniques consists of military officers and defense analysts. Ever since the Prussian army embraced von Reisswitz’s kriegsspiel system two centuries ago, various forms of wargames have played a significant role in military training and war planning (Allen 1987; Perla 1990; von Hilgers 2012). Defense wargaming and simulation have become increasingly computer-based in recent decades (Wilson 1969; Hausrath 1971; Smith 2009), but manual techniques also persist, and the defense community forms the main target audience for the major international conferences of more than one hundred wargame professionals that I have co-organized at King’s College London since 2013. (The proceedings of these Connections UK conferences are available at <http://www.professionalwargaming.co.uk>.)

Figure 35.1 Techniques used by different groups to study armed conflict.

In this chapter, I will draw on my own experience to explore the potential and problems of using wargames in the more unfamiliar context of academia. First, I will discuss what wargames can contribute to supplement more traditional means of scholarly study. Then I will assess the relative merits of manual and computer wargames, and explain why I make more use of the former. Next, I will talk about my long experience of getting my postgraduates to design wargames for themselves on conflicts of their choice. I will proceed to consider the practical obstacles and trade-offs that impede wider academic employment of wargaming techniques. Finally, I will discuss why wargames evoke such stigma in scholarly circles, and suggest how this stigma might best be overcome.

War and games might appear to be utterly dissimilar activities, but in fact they share certain characteristics that go back as far as the days of medieval tournaments and the gladiatorial contests of ancient Rome (Cornell and Allen 2002; van Creveld 2013; Huizinga 1970, chapter 5). My favorite articulation of this relationship is Carl von Clausewitz’s claim (before the rise of kriegsspiel) that “in the whole range of human activities, war most closely resembles a game of cards” (Clausewitz 1976, 86). Adversarial games artificially generate the kind of stark conflictual relationship that is so characteristic of war, but that is relatively rare in other kinds of human interactions. As a result, games can mirror some of the distinctive dynamics of war, in particular the action-reaction contest that develops as each side tries to get the better of an active and thinking opponent. Edward Luttwak has written vividly of the “paradoxical logic” that characterizes war and games, with antagonists often deliberately choosing “inefficient” approaches such as attacking through the poor terrain of the Ardennes forest in 1940 and 1944, in order to surprise their opponents and catch them unprepared (Luttwak 1987).

So what can wargames add to the millions of books and research studies about war, which already do a pretty comprehensive job of capturing these interactive conflict dynamics through the safe vicarious media of words and maps? The key difference is that books about past wars only report on what happened on the single occasion when the conflict happened for real. Wargames, by contrast, bring certain very limited and selective aspects of the conflict “back to life” and allow it to be refought as an endlessly replayable game of “glorified chess” (Dunnigan 1992b, 13). Wargames about potential future conflicts offer the much greater attraction of allowing defense planners to experiment safely with strategies and options before doing anything for real, but here the absence of even the single historical precedent available when modeling past conflicts makes it commensurately harder to know if the wargame accurately reflects what might happen in the real world (Sabin 2012, 130–132 and chapter 4).

One key contribution of wargame modeling in either case is that it forces users and designers to engage systematically with questions that are all too easy to neglect when simply reading or writing about the conflict situation concerned. Wargames by their very nature are less concerned with stories and anecdotes and more focused on the deeper underlying dynamics of the situation. What was or is the strategic and political geography of the entire theater (not just the part where fighting happened to occur historically)? What alternative options were or are available for force deployments? What were or are the antagonists actually trying to achieve militarily and politically? What was or is the relative importance of influences such as numbers, quality, morale, leadership, culture, intelligence, logistics, terrain, weather, and time? How plausible are alternative outcomes to the contest, and what might trigger such divergence? Wargame modeling is an incredibly ambitious enterprise in that it seeks to create in miniature a laboratory within which human conflict in all its complexity may be represented and experimented upon, but if it succeeds even slightly in this endeavor, it may raise questions that would have been overlooked had analysts restricted themselves simply to writing about known facts.

A second key contribution of wargames stems from the decision element. Mathematical modeling of force capabilities is supplemented in wargaming by the equally important element of interactive player decisions to determine what strategies are actually pursued. The players themselves benefit from a unique form of active learning, since instead of merely reading or hearing about the choices available, they must weigh up the options and decide for themselves, and then make follow-up choices once they see the response of their active opponents. This is a very powerful way of giving players an intuitive understanding of the force-space-time dynamics in the actual conflict, as well as of key military dilemmas such as how to balance attack and defense across key sectors and whether to reinforce success or salvage failure. From a research perspective, seeing the decisions that players make across repeated plays of the game, and their consequences in terms of game outcomes, offers useful experimental information that supplements any single real historical precedent and allows better informed discussion of variability and contingency.

This leads on to a third key contribution of wargame modeling, namely that it provides much stronger feedback as to the limitations of the designers’ and players’ understanding of the situation. Traditional scholarly media such as books and lectures focus on the one-way transmission of information and ideas to a more or less receptive audience. Wargames, by contrast, are complex interactive devices that usually fail badly when first tested, and that need to be refined through a process of iterative correction that provides very useful feedback as to the deficiencies in the initial design assumptions (Berg et al. 1977, 44 and 52; McCarty 2004, 256). Anyone can draw blocks and arrows on an unresponsive map, but it takes days and weeks of very instructive testing and iterative refinement to get the player-guided actions of units in a wargame to resemble even vaguely those of their real-life counterparts. Not only that, but it is far more evident from their active choices and discussions whether the players themselves really understand the dynamics of the modeled situation than it is from sage nodding in a traditional lecture hall, and so it is easier to identify where further discussion is required.

I build on these particular contributions of wargames by using them as a judicious supplement to more conventional educational methods of lectures, seminars, debates, private study, and essay writing across the range of my undergraduate teaching in military history. Students use over a dozen different wargames to study the intertwined military and political characteristics of the Second Punic War, the operational and strategic dynamics of World War II, and the shifting tactical and operational features of air warfare over the past century (Sabin 2012). My most ambitious use of wargame modeling as a scholarly technique was in my 2007 book Lost Battles, which seeks to cast new light on the vexed controversies over how to reconstruct individual Greek and Roman land battles by developing a common wargame system with which three dozen such contests may be refought, thereby allowing proposed individual reconstructions to be tested against generic overall patterns and against sensible player choices through a process of “comparative dynamic modeling” (Sabin 2007). I will return shortly to my other equally ambitious use of wargames as an educational device, but first I will discuss which medium for wargaming offers the greatest academic benefits.

The microchip revolution has transformed wargaming as it has so many other areas of modern life over the past few decades, and many people understandably think that any form of “simulation” now inevitably involves computer systems. Recreational video games, including military first-person shooters like the Call of Duty series, now have a bigger turnover than Hollywood films, and are played by significant proportions of the population (Halter 2006). As I mentioned, professional military wargaming has been dominated by computers for decades (Smith 2009; Mead 2013). However, as the present book makes abundantly clear, manual wargaming is far from dead—in fact, more different manual wargames are being published today (albeit in diminished volumes) than ever before (Chupin 2011). I will now assess which type of wargame offers the greater payoff for academic purposes (an issue I discuss at greater length in Sabin 2011).

Computers come into their own for their ability to conduct rapid calculations and apply programmed rules automatically. This allows them to run complex and detailed models at speeds entirely unattainable by other means. Academics have sometimes used this for “agent-based modeling” of the actions of thousands of individual entities using artificial intelligence routines, as in John Haldon’s research project on Byzantine logistics (Haldon et al. 2010). I use similar capabilities within commercial computer wargames by having top-down map-based representations of air raids in the Battle of Britain and Vietnam play out automatically in real time on the projector screen while I discuss with my students the tactical interactions and intelligence issues involved.

The other area where computers shine is in portraying complex virtual 3D worlds from a real-time first-person perspective. Here again, it is in my air warfare teaching where this is most relevant, and I use various commercial combat flight simulator games to allow single students to take control of a fighter plane in dogfights of different eras while the rest watch. The beauty of this vivid way of bringing air combat tactics to life is that it takes only tens of minutes even for multiple iterations of the simulation, allowing the majority of the class to proceed along more conventional lines so as to consolidate the insights gained. I need to choose the games carefully and avoid the many distorted “arcade” portrayals of the subject, and even with more credible simulations, it is important to make clear to students such unavoidable artificialities as the absence of g-forces and of the life-and-death stakes that make real pilots more cautious than our virtual pilots invariably are!

Although I am entirely familiar with other commercial computer wargames that cover other aspects of my military history modules, I do not use them in class, for a variety of reasons. There are not actually that many credible computer wargames that still run on modern operating systems and avoid the arcade distortions so prevalent in the mass entertainment market. Those that do exist tend to be obsessively detailed and time-consuming representations with hundreds of units (see <http://wargamer.com>), very far from the “pick up and play” character of the first-person simulators. The costly suites of networked computers used in military wargaming are less readily available in an academic context, so it is far from easy to give multiple students simultaneous direct involvement in the game. Not only that, but the computer displays which have such advantages in portraying fast-moving real-time 3D images are less comparatively attractive for showing units on a strategic map. Large physical maps and counters have more tactile appeal, are better suited to the human eye’s combination of central acuity and breadth of vision, and allow competing players to engage with one another face to face instead of by staring at a screen.

Published manual wargames have their own severe limitations as vehicles for academic study. Although they are less infrastructure-dependent, far more numerous, and less prone to arcade distortions than mass-market computer games, they are still primarily entertainment products rather than scholarly endeavors, and many of them are poorly researched and documented and offer only questionable and superficial reflections of the conflicts they purport to simulate (Sabin 2013). A much bigger problem is that the many published manual wargames that do offer a credible and worthwhile simulation of real conflict dynamics are at least as complex, detailed, and time-consuming as are serious computer wargames. With hundreds of counters to set up, and with rulebooks dozens of pages long to be mastered and applied manually, it is readily apparent that most commercial board wargames are even less suitable for class employment than are their computerized counterparts (as is evident from the thousands of reviews and images at <http://www.consimworld.com>, <http://grognard.com>, and <http://boardgamegeek.com>).

What swings the balance decisively in favor of manual games, in my own view, is design accessibility. Very few strategic studies scholars or students have the programming expertise to do much more than play computer games as they come, warts and all. Manual games, in contrast, expose their rules systems as a necessary component of learning to play them, and if one disagrees with their assumptions, it is fairly simple to tweak the rules or scenarios to accord better with one’s own judgment. I already emphasized in the previous section that visible and flexible systemic modeling of conflict dynamics is a key part of the distinctive contribution that wargames can make to our understanding of war. This contribution is significantly weakened if the game system is concealed within an unmodifiable “black box” of computer code.

Although worthwhile published manual wargames are almost all too complex and detailed to play in class, this is not a necessary characteristic of manual wargames per se. Some published board wargames take the form of small “microgames” (Nordling 2009), though they are of very variable quality and utility. Based on the examples and ideas in the many hundreds of manual wargames of all sizes that I own, I have designed my own smaller and simpler microgames with only a few dozen counters and a few pages of rules, which are precisely tailored to highlight the conflict dynamics which I want my students to grasp. It is these personal designs that underpin the great majority of my academic wargaming. Almost all of my designs are available online for free download (Google “Sabin consim”) or are in my two latest books: Lost Battles, which I have mentioned already (Sabin 2007), and my recent Simulating War, which contains the rules and components for eight other complete wargames (Sabin 2012). I will discuss shortly the practical problems with using even such simple tailored wargames in an academic context, but first I will outline the most significant educational innovation that the invaluable design accessibility of manual wargames has allowed me to develop over the past decade and more.

Among the most important insights of wargaming guru James Dunnigan about manual wargames is that “if you can play them, you can design them” (Dunnigan 1992b, 252–253). Having seen the truth of this aphorism myself through my own wargame designs, I decided to make it the centerpiece of a new elective module for our MA students, in which they design their own simple wargames on conflicts of their choice, from ancient times to the most recent wars. The aim is to help the students to develop a deeper understanding of their conflict’s dynamics than they would gain simply by writing a conventional essay, while also teaching them about conflict simulation as a methodology in its own right. A further key benefit is that successful wargame design requires a very rich mixture of intellectual skills, ranging from focused research and analytical creativity to legalistic clarity and graphic design, as well as the teamwork needed to help test and refine one another’s developing projects. It is precisely these skills that are in prime demand for a wide range of modern careers.

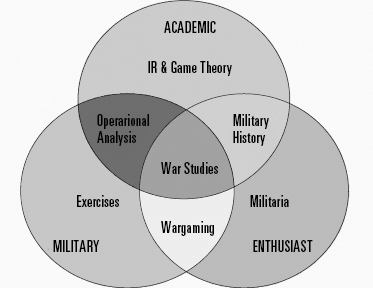

The module has been running since 2003, and over a hundred students have now completed it and produced individual simulation projects. Around half of these projects have been posted online for free download for the benefit of future students and others (again, Google “Sabin consim”), and a few have gone on to be published as hobby wargames. I am especially pleased that the gender balance of the students has not been as stereotypically male-dominated as one might expect for such a wargame course (van Creveld 2013, chapter 7). As figure 35.2 shows, seven of the fifteen students on my latest module were female. The course has evolved significantly through experience and student feedback, and several lessons have emerged that I will now set out for the benefit of anyone else thinking of starting such a module (as Richard Barbrook from section V of this book did a few years ago).

Figure 35.2 My MA students learning to play simple published wargames.

One lesson is that such a module requires an unusually large commitment of time, both from the students and from the teacher. Designing wargames is a prolonged and iterative process, and my module stretches across two full terms, during which the students spend significantly longer on this course than on their other equivalent modules. This is not necessarily a problem as long as they are warned up front, since (as Rex Brynen has found with his own intensive peace-building simulation), modern students are actually keen to be challenged and stretched in return for their high fees. The greater teaching time required to supervise and mark wargame projects compared to conventional essays or dissertations is a bigger problem in today’s increasingly pressurized and efficiency-conscious university environment—even a full class of sixteen students is a big strain, and any more would be impractical in my view.

A second lesson is that the initial understanding of the students is extremely variable. Some of them are experienced wargamers, but most (despite being very intelligent and accomplished in traditional essay and exam techniques) find it a real struggle even to play simple wargames at the start of the course. Some have a lot of trouble with practical matters such as understanding the difference between battalions and divisions, making sense of basic statistics and probability, or using graphics software to create the maps and counters. I have found that the key to tackling this variable understanding is to make maximum use of teams of four students, each working on broadly related simulation projects. The more experienced team members can help the others grasp the basics, while the less experienced students can perform in return the equally vital service of helping their overambitious colleagues to simplify their own designs and produce intelligible games that can be played within the crucial two-hour time constraint. Those with prior wargaming experience usually start out by trying to retain too much of the detail and complexity of published wargames, and it is often the neophytes who are better at focusing on the essentials and abstracting peripheral details.

A third lesson is that most students find it as hard to grasp abstract design theory as they do to understand wargame rules. Not until they actually play specific games for real do things become clear. By far the most common request in student feedback has been for more time playing and experimenting with games instead of just talking about the design issues involved. Now that the design theory from my early course lectures has been set out in full within my latest book Simulating War (which is very much the textbook for this module), I can afford to talk less and leave more time for the students to try things out for themselves with the help of my own teaching games and the simplest published manual wargames. Nothing could illustrate better the point I made earlier about the utility of wargames as an active learning technique. Students now routinely opt to get together in their teams outside class to play various wargames, including their own evolving designs, and so supplement the inevitably limited class time itself.

A final lesson is that the students need to be shown that wargaming is not just a recreational pastime, but also something that has real professional utility. Although the published wargames I lend to the students to help with their own designs are perforce hobby games, I acquaint the students as much as possible with my own academic and defense wargaming activities, and we always have a guest session with one or more defense wargame professionals to reinforce the point. Former students on the course often return to help their successors, and they can attest further to the utility of their studies in their own careers. I will return in the final section of this chapter to this key issue of the credibility of wargaming as an academic activity.

Unlike in hobby wargames, my students are required to devote around half the words in their simulation projects to historical analyses, design notes, and reflective essays that explicitly attest to the research effort and learning experience involved, and I will conclude this section with a few telling extracts from the most recent reflective essays:

As the last comment mentions, there are significant practical challenges associated with creating and using wargames in academia to give a worthwhile reflection of real conflict dynamics. I would highlight three interacting constraints that limit what it is practical to achieve, namely time, expertise, and resources. I will say something about each constraint in turn, and then discuss how I have sought to tackle the associated obstacles and trade-offs within my own academic employment of wargaming techniques.

Time is a problem because (as I have said) the great majority of published wargames except first-person computer simulators take a long time to learn and play. Whereas one can skim quickly through books and articles to get the gist of the argument, or highlight only the key points during a lecture or conference address, this shortcut is not easily available with wargames. Enthusiasts and military users are often prepared to spend days playing an individual wargame (Perla 1990), as are some academics for whom the game (typically a pol-mil simulation) is a one-off centerpiece of an entire course (Brynen 2010). However, my own preference is to use multiple different wargames to cover diverse aspects of conflict, and to do so as a supplement to traditional scholarly techniques such as debates and seminar discussions. Time is hence at a premium within crowded conference schedules or within the standard weekly two-hour classes of a taught module.

Expertise is an equally important constraint because those who have never played wargames before find it difficult to understand even simple versions just by reading the rules rather than by practical hands-on instruction. My MA course shows that this barrier can be overcome in time, but newcomers without such support find the complexity and unfamiliarity of wargames utterly offputting. Humanities students and scholars find it even harder to comprehend explicit mathematical models of conflict constructed by analysts like Stephen Biddle (2004), but at least they can grasp the verbal conclusions that such authors draw—manual wargames, by contrast, demand that the system be understood properly in order to play them at all. As I have said, some computer wargames (especially first-person simulators) can be “picked up and played” with much greater facility, but only experienced computer programmers can modify or create them.

Resources are a further significant limit on academic wargaming. It is almost unknown for scholarly libraries and archives to hold any of the many thousands of wargames that have been published over the past six decades. Preserving the loose-leaf maps and hundreds of separate counters in board wargames, or maintaining or emulating the rapidly dating hardware and software needed to run successive generations of computer wargames, are significant challenges and disincentives in their own right. Although it would be easier in principle to preserve the many thousands of issues of specialist magazines commenting on this growing corpus of wargames, the lack of scholarly interest in the technique means that such collections that survive are almost all in private hands. Digitization of magazine archives (as at <http://www.wargamedevelopments.org/nugget.htm>) has made their study more practical, and John Curry (<http://www.wargaming.co>) is doing wonders in preserving and republishing key wargaming books and rulesets (as he describes in part I of this book), but most wargames are accessible only to those who have already collected them or who are willing to buy used copies while the secondhand market endures (Sabin 2012, appendix 2; <http://www3.telus.net/simulacrum/main.htm>).

These three constraints of time, expertise, and resources interact to make it very challenging to give individual students, conference participants, or fellow scholars a rich and realistic decision experience through the use of wargames. If simulation were not an issue and all that mattered was to run a challenging abstract game, then one could simply distribute plenty of cheap chess sets and have everyone play one another. Likewise, if player decisions were not required, one could simply select a realistic computer wargame and have it run automatically while everyone watched and discussed the unfolding representation (as I actually do in my Battle of Britain and Vietnam air war classes). The problem lies in combining simulation with decision dilemmas, since it takes very clever game design to embody realistic decision options and trade-offs within a wargame on a particular conflict, without making the resulting game system too complex and time-consuming for users to grasp and employ it effectively at all (Sabin 2012, 117–124), and without unduly encouraging unrealistic behavior aimed at exploiting the artificial game system itself (Frank 2012).

My own response to this challenge has been on several levels. First, I have spent decades amassing my own personal collection of more than a thousand published wargames and an even larger number of issues of specialist magazines. Based on this enormous archive, I have honed my design skills through repeated iterations so that I can create tailored wargames that capture key conflict dynamics as simply and accessibly as possible. (For example, my Lost Battles system evolved through a series of related designs stretching back for over twenty years [Sabin 2007, xix].) It is these personal wargame designs that I use in my academic work, for instance in 2014 when I created a simple centenary kriegsspiel of the 1914 campaign in France and Belgium (available at <http://professionalwargaming.co.uk/2014S.html>) for use at a World War I counterfactual conference I organized at Windsor Castle with my colleague Ned Lebow and on a couple of occasions later that year. I make my designs as widely available as possible through my books and websites, and I receive a steady stream of messages from academics all around the world who have been inspired thereby to employ wargaming techniques for themselves.

The second level of my response has been to develop wargaming expertise among my postgraduate students. To make up for the lack of wargames in the college library, I lend each of my master’s students a few wargames from my personal collection on topics related to their own chosen conflict, and I use my own design experience to help advise them how to create their own simple wargame simulations. In return, some of my master’s and research students act as teaching assistants to help me to run wargames in my various BA modules, as well as in wider events such as the 1914 kriegsspiel just mentioned. I run a practice session with my assistants before each class or event, in which we play through the game together to ensure that they understand the nuances of the rules and the tactical situation. The ultimate example of synergy between my postgraduate and undergraduate teaching is that the wargame that we use each year to study Hannibal’s campaigns in my BA ancient warfare module started out in 2006 as the MA class project of my student Garrett Mills, before being redesigned and published under our joint names in 2008 (Sabin 2012, 145–160).

Figure 35.3 My BA students being helped to play one of my own wargame designs.

The third level of my response to the challenge of reconciling realistic decision involvement with system accessibility is to employ an approach of “guided competition.” Since students and conference participants alike are almost all nongamers who would feel at sea if left alone even with the simple games of my own design, most of my games are run by facilitators whose role is to help apply the detailed rules, to keep the games moving quickly, to advise the students against egregious tactical errors, and to lead initial discussion of how far the simulation reflects real conflict dynamics. Having postgraduate assistants available as facilitators allows me to run three or more simultaneous games as shown in figure 35.3, while I myself move between them to maintain an overview and keep things running smoothly. With six to eight players per game, the opportunity for individual decision experience is obviously diluted, but having teams of around three people command each side does have the significant benefits that those with a stronger grasp of the system can help their colleagues and that decisions need to be debated explicitly—a key educational advantage. A final plenary session in the class or conference as a whole allows the experience from the individual games to be shared and the issues to be debated with reference to the real conflict that we are trying to study.

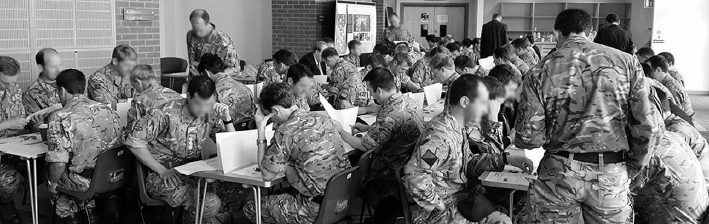

The final way in which I reconcile decision involvement with system accessibility is by designing some wargames that are so simple and quick that I can leave players to run them for themselves in multiple one-on-one contests after all. I have done this several times over the years, and the best example is the drastically cut-down version of my 1914 kriegsspiel with just one rather than four pages of rules, which I ran with several dozen participants at a British Army wargaming workshop in 2014 (as shown in figure 35.4) and again at our Connections UK conference at King’s College (<http://www.professionalwargaming.co.uk>) later that year. The game system needs to be really simple, and I need to spend significant time at the start of the session explaining the rules and running through an illustrated example for the group as a whole. This makes it vital that the game itself can be played quickly, especially since it is preferable to have the players immediately swap sides and play the game a second time to get the most benefit from their initial investment in learning the system. My 1914 mini-game proved a great success in its intended role of giving players a quick hands-on introduction to wargame dynamics and showing that wargames can still capture key strategic dilemmas without being impossibly complex.

Figure 35.4 British Army officers playing my 1914 mini-game one on one.

These are only my own responses to the practical challenges of using wargames in an academic context. Other approaches are entirely feasible. For example, George Phillies, a physicist at Worcester Polytechnic Institute in Massachusetts, has published several books and a freely available YouTube lecture series on wargame design, focusing on classic commercially published board wargames from the 1960s (Phillies 2014; <http://www.wpi.edu/academics/imgd/news/20134/174110.htm>). Scholars who are already familiar with wargames will be able to devise their own ways of overcoming the practical obstacles and trade-offs I have discussed. What is much more difficult is for those with little or no prior experience of wargaming to develop wargame courses or activities, as military officers and academics working with military students are sometimes asked to do. My MA course shows that the necessary skills can be learned with the proper input of time, expertise, and resources, but wargaming cannot simply be “picked up” swiftly by unsupported browsing of the literature as some other subjects can. What is needed for proper professional institutionalization of wargaming is much more structured hands-on education by existing experts, and here a key obstacle is the skepticism of many nongamers (especially in academia) about the value of the technique as a whole.

I discussed at the start of this chapter the failure of wargaming proper to attain anything like the scholarly respectability of approaches such as mathematical modeling, operational research, game theory, simulation, or pol-mil gaming. Even those books and academic courses that focus squarely on the military conduct of particular battles or wars almost never mention the existence of detailed wargame simulations of the conflicts concerned. Martin van Creveld is one of very few nongaming scholars who have written about the various forms of wargames, and he treats them as sociologically interesting objects of curiosity rather than as potentially useful techniques of enquiry (van Creveld 2008; 2013). Rob MacDougall and Lisa Faden discuss this attitude further in their own chapter later in this section. As Pierre Corbeil wrote recently, “the power of the game as a tool for the study of possibilities has not been adopted by the historical profession as it exists in the universities of the world” (Corbeil 2011, 419). Why should this be?

One reason is simple ignorance, due to the very low profile of serious wargames in wider society. Professional military wargaming is a sensitive area cloaked by security restrictions, to the point where a student of mine could find few practical details of US Army wargames conducted prior to the 1991 Gulf War even after interviewing the key participants. I myself have not been allowed access to most tests of a planning wargame that I am helping to design for the UK defense ministry. Recreational wargames are unclassified, but they are sold by specialist outlets and reviewed in specialist magazines, so they have very little visibility outside the hobby community. One famous historian told me recently that he was not necessarily prejudiced against wargames—he simply knew almost nothing about them. Air historian Alfred Price wrote that, “I had a rather fuzzy pre-conceived notion that wargamers were grown-ups who played around with kids’ toys, and tried to make out that they were making some serious contribution to military understanding in the process” (Spick 1978, 7).

This leads on to a second problem, namely the widespread perception in society as a whole, and even among some self-conscious hobbyists themselves (McGuire 1976), that wargaming tends to attract childish nerds. Jane McGonigal has written perceptively of the stigma attached to the words “game” and “play” (McGonigal 2011, 19), and scholars have coined the term “serious games” to try to offset the negative connotations involved (Abt 1970; Smith 2009). The word “wargame” has precisely the opposite effect, since it suggests that the tragic sacrifices of armed conflict are being reduced to a mere “game.” There are even suspicions that some wargamers are closet militarists with an unhealthy admiration for Nazi military prowess (Smelser and Davies 2008, chapter 7). Small wonder that wargamers are usually very reticent about their activities, and make extensive use of euphemisms. As Jim Dunnigan wrote, “A wargame is a playable simulation. A conflict simulation is another name for wargame, one that leaves out the two unsavory terms ‘war’ and ‘game’” (Dunnigan 1992b, 236). (On the vexed terminological distinction between simulations and games, see Klabbers 2009.)

A third reason for wargaming’s image problem is that it is seen primarily as a recreational activity for private enthusiasts instead of as a valid scholarly tool like game theory. Academics are often uncomfortable engaging with “popular” works in their field, since they are seen as lacking the objectivity and specialist rigor of proper scholarly studies (Overy 2010). As I have said, many published hobby wargames amply merit such suspicions, because of their poor simulation and arcade distortions. Some defense wargamers such as Robert Rubel have called for greater professionalization within the military wargame community (Rubel 2006). However, it is far from clear that wargames ever can approach the attempted “scientific” rigor of works of operational analysis like those by Stephen Biddle and David Rowland (Biddle 2004; Rowland 2006). Even if they exploit every scrap of available real-world data, wargames contain so many subjective choices in their mechanism and structure that skeptics will always be able to challenge their assumptions and dismiss them as guesswork and invention. Veteran US defense wargamer Peter Perla is very clear that “designing a wargame is an art, not a science,” and he suggests that “game design has no real formalisms. Instead it is dominated by individual style and fashion, and in that respect is more like painting than other arts” (Perla 1990, 183–184).

The fourth reason why wargames attract such skepticism lies in the variability of their outcomes. Wargames offer a powerful means of exploring the role of contingency within war and conflict, but such “counterfactual” speculation is a very controversial technique in scholarly circles. Although there have been several recent works of popular history that have explored “what if?” questions, especially regarding World War II (e.g., Tsouras 2002; Showalter and Deutsch 2010), and although some prominent historians such as Andrew Roberts, Jeremy Black, and Niall Ferguson have championed this counterfactual approach (Roberts 2004; Black 2008; Ferguson 2000), most historical scholars remain doubtful and prefer to focus on what actually occurred (Collins 2007). My colleague Ned Lebow (with whom I organized the World War I centenary conference at Windsor Castle) has written thoughtfully and eloquently in theoretical defense of carefully framed counterfactual speculation (Lebow 2010), but eminent historian Richard Evans has gone beyond the usual attitude of silent skepticism and written an entire book articulating the contrary view (Evans 2014). For those who think it pointless to ask “what if” history had gone differently, historical wargames founded on this very premise of contingent variability are unlikely to hold much attraction.

The variability of wargame outcomes attracts skepticism for other reasons as well. Whereas automatic computer simulations can be run thousands of times to generate a statistical spread of outcomes, wargames with human players are more time-consuming to repeat, and so there are understandable fears that individual results may be unrepresentative. A particularly sore point lies in the use of dice as a quick abstract means of modeling detailed uncertainties (Rubel 2006, 119–120). In real war, bad luck such as orders going astray is impossible to challenge and clearly attributable in hindsight to a specific causal chain, but an unlucky die roll in a wargame seems abstract and arbitrary by comparison, and raises uncomfortable parallels with games of pure chance such as Snakes and Ladders. In my kriegsspiel games in 2014, I deliberately used limited intelligence rather than die rolls as the means of generating uncertainty and random variation, since it was more acceptable to the officers and academics involved. My other wargame designs are more open because I specifically want players and facilitators to have full visibility of the interactive dynamics involved, but the use of dice is a constant credibility problem, despite being fully justified in simulation terms to avoid unrealistically chesslike calculations by the players (Sabin 2012, 117–120).

After many years of experience in using and promoting wargaming techniques within academia, I now have a pretty good idea of the reaction from the scholarly community. Academics who are themselves recreational wargamers (from a wide range of subject disciplines) tend to be very supportive, and relieved that they can admit their interest and discuss the problems and possibilities of wargame modeling as a scholarly technique. My books have sold several thousand copies each, and have spawned flourishing Yahoo discussion groups with hundreds of members and many more words in their thousands of posts than there are in the books themselves (<https://groups.yahoo.com/neo/groups/lostbattles>; <https://groups.yahoo.com/neo/groups/simulatingwar>). I have given lectures on my simulation studies at universities in several countries, and I have become increasingly involved in discussing, promoting, and designing wargames within the professional defense community. However, nongaming scholars, especially in military history, have paid very little attention to my work. Most seem not even to have noticed it, or have dismissed it as some strange enthusiast aberration. Only in journals such as Simulation & Gaming or in books like the present one are games of this kind really taken seriously in the academic environment, and nongaming scholars are very unlikely to read such sources in the first place or to be persuaded easily even if they do. My extensive use of wargames as an educational vehicle has been accepted without too much trouble, thanks to positive student feedback and a predilection in the university system for novel methods of assessment. I won a King’s College award in 2009 for innovative teaching, and one external examiner praised my MA module for providing “fascinating assessment and a welcome change to the usual chore of essays.” It has been a very different story as regards research. My Lost Battles book has made little impact among professional ancient historians, and when I proposed a similar study of ancient naval battles as part of a major interdisciplinary research grant application, my contribution was dismissed by one reviewer as “just wargaming.” King’s College has not risked submitting my various articles on wargaming (Sabin 2002; 2011) to our national research evaluation exercise for fear of a similar reaction, nor did it submit my latest book (Sabin 2012) despite a thirty-seven-page bibliography and a scholarly review that said, “If I had to recommend one military history book I have read this year it would be Philip Sabin’s Simulating War” (<http://smh-hq.org/smhblog/?p=516>). It is lucky that I was already a full professor before I started publishing seriously about wargaming, since in the current academic environment it is difficult even to keep one’s job with research this controversial, let alone to get appointed or promoted. I am very conscious that, when I retire, my modules will probably be replaced with more conventionally taught ones, and wargaming at King’s will disappear with hardly a ripple.

So is there any way to rescue academic wargaming from the stigma and skepticism and to set it on a more secure foundation? To my mind, the only practical way forward is to build on and expand the small core of scholars who are already knowledgeable about and sympathetic to wargaming. There will always be many academics who remain irredeemably skeptical (with considerable justification given the many problems and limitations of the technique), but there are also surprising numbers of scholars who do find wargames interesting and enlightening but who have been hiding their light under a bushel hitherto for fear of ridicule or of being accused of “bringing their hobby to work.” The more that they see other academics using and writing about wargames, the more emboldened they may be to join in and to try something for themselves. With even nongaming academics sometimes being asked now to run wargames for military students, we may at last be approaching the day when wargaming experience is something to be mentioned proudly on a CV instead of tactfully concealed from skeptical appointments panels.

As regards the best way of showing anyone from students to professors what wargames have to offer, I am convinced that there is no substitute for actually playing games so that people can see for themselves. That is why I am so keen on designing simple and accessible wargames that can be played within a very short time. The initially skeptical Prussian chief of staff was famously converted and persuaded to give his full backing to the original kriegsspiel when he actually saw it in operation (Perla 1990, 26). I have lost count of the number of times that players of my own wargames have had similar revelations, and registered their amazement that a few dozen counters and a few pages of rules can reproduce real campaigns and reflect real military dynamics and dilemmas. Books like this one are all very well as far as they go, but the more people who are directly exposed to serious but accessible wargames, the less pervasive will be their image as trivial and childish diversions or impossibly complex and time-consuming pastimes for obsessive nerds.

Philip Sabin is Professor of Strategic Studies in the Department of War Studies at King’s College London. He has written or edited fifteen books and monographs and several dozen chapters and articles on a wide variety of military topics, as well as designing several published wargames. His current research specialism is the analytical modeling and simulation of the key dynamics of armed conflict, as reflected in his two recent books Lost Battles (2007) and Simulating War (2012). He has decades of experience in using wargames to teach military and civilian students, including through his MA module in which students learn to design their own wargames on conflicts of their choice. He has close links with the armed services, lectures internationally on wargaming and other military topics, and is co-organizer of the annual Connections UK conference for wargames professionals.