In 1975, my senior year of engineering school, I was already a published game designer (having published the magazine JagdPanther since 1973) and had been to the first Origins convention. One afternoon, while watching Star Trek reruns, I was playing Jutland, a 1967 game about World War I battleships that tracked damage by marking off rows of little boxes. Inspired, I grabbed a pad of graph paper, which every engineering student had, and began working out how I would design a starship combat game. Going beyond Jutland, which simply “turned off” a gun turret for every few damage points, I established boxes for each system on the starship (weapons, power, tractor beams, transporters, shields, and so on)—the first time anyone had done this.

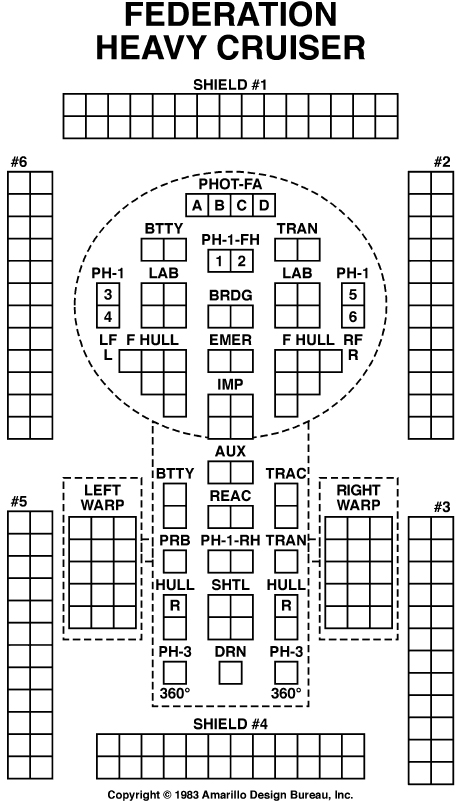

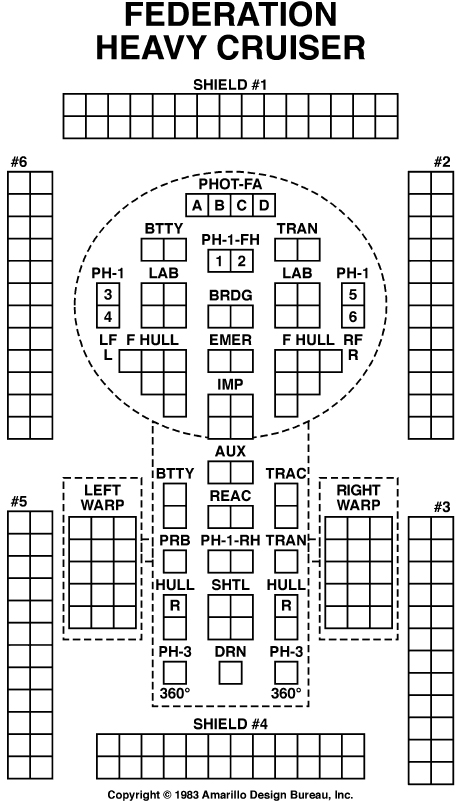

The ship was laid out in a pattern that more or less followed the “actual” ship seen on television: a round saucer, a secondary hull, and two engine nacelles on pylons. The weapons were located where they were seen on the screen, and the various official and unofficial blueprints that had been published showed the location of some other key external features such as the bridge and shuttle bay. Everything else was fitted into any convenient places in the overall framework. The idea of a “ship diagram that looked like a ship” was intended to make the player feel that he really was driving a starship. Previous games on various subjects had largely just handled checkboxes as rows and columns with no particular effort to look like a tank, airplane, or warship.

The state of graphic arts in 1975 was nowhere near what it is now. Game graphics were made using thin black tape, a razor knife, rub-on lettering, and a sheet of paper with blue grid lines. Each ship was about two feet square and took a day or two to complete. The arrival of computer graphics in the early 1980s would change everything, but that was still in the future.

The movement system started from air combat games like Richthofen’s War (1972) but quickly moved far beyond that, providing for the simultaneous movement of dozens of ships, small craft, missiles, and torpedoes. Previously, air combat games moved one aircraft at a time through a series of maneuvers (usually out, turn around, close back in). I wanted my players to be able to fire at any point during the movement of the units, and for the units to move at the same time. The game was playtested with one ship against one ship for three years before anyone tried to fight a larger battle, and all of the core elements were hardwired into the system based on what players could handle with one ship. Shortly after publication, however, players were engaged in ten-on-ten battles without difficulty.

Within twenty-four hours, I had invited a gaming buddy to test the first rough design of what led to Star Fleet Battles (SFB) (1979), which already included the new concepts of energy allocation, damage allocation, and proportional movement. Under that system, ships paid for a speed and moved during a proportionate number of the turn’s thirty-two impulses, spread out during the turn.

Hand-drawn copies with roughly typed rules were a favorite at the office of JagdPanther, but everyone knew we did not have any legal basis to publish the game, so it remained only a private amusement. It continued to grow, with new rules, ships, and scenarios. I had been a casual fan of the TV series but now started buying whatever books, manuals, drawings, and technical information I could. By the spring of 1977, JagdPanther, never designed to make a profit, had closed down after paying all of its bills, and I took up a new interest—Leanna Williams, marrying her that fall. But the wargaming bug would not die.

My gaming buddy and former JagdPanther partner Allen Eldridge and I began thinking in 1978 of forming a new game company. We looked into the industry for a workable business concept. We found two ideas that appealed to us: pocket games (pioneered by Metagaming) and—a first for the industry—no sales to anyone but wholesalers, just to reduce the workload. We sought advice from many people in the game and hobby industries, and decided that to get into the wholesalers we would have to offer four games on the first day. By the spring of 1979, we had plans well in hand. The name “Task Force” was a military term for a mixed organization of combat forces, one that had featured prominently in some game concepts. The term had stuck in our minds and became the company name.

One evening, I was chatting with my friend and mentor Lou Zocchi about industry practices and trends when I mentioned that it was a shame we could not print the “Star Trek game I designed in college” because there would be no way to get a license for such a small project. Lou Zocchi put us in contact with Franz Joseph Schnaubelt, the engineer who designed the USS Enterprise for Paramount and published the Star Trek Star Fleet Technical Manual (1975). Franz Joseph, as he was popularly known, had licensed Lou Zocchi to do his Star Fleet Battle Manual (1977) and the original plastic starships (which sparked a hundred lines of miniatures by dozens of companies). Franz agreed to license Task Force to do a “sort of Star Trek–like game” within strictly defined limits. Franz had no part in the actual game design, and all of his input came from his book rather than from himself.

At the time the game was designed, electronic games were at the level of a screen of “periods” with a “K” to indicate where the Klingon ship was located, so there was no influence from that source. Since then, several computer games have been based on Star Fleet Battles (legally or otherwise), including the best-selling Starfleet Command series.

The pocket edition of Star Fleet Battles appeared (with three other pocket games) at Origins 1979. Task Force stumbled into a major bit of luck, in that the dominant game publisher of the day had upset the entire industry by selling games at wholesale terms to individual gamers. The retailers and wholesalers were outraged by this policy, which undercut their own sales. A near-riot erupted at Origins in front of the dominant company’s booth, demanding that the company stop the practice and preferably end all direct mail orders. The president of that company told the wholesalers, “Nobody sells only to wholesalers!”—only to hear Allen Eldridge (in the booth next to theirs) announce, “That’s how we do it!” A few wholesalers who had already been contacted by Task Force confirmed that this was true. Delighted, every wholesaler in the industry (and every retailer at Origins) signed up to carry Task Force Games products on the spot.

Task Force Games, recognizing we had a winner, sold out of the pocket game in a month and reprinted it as a boxed game with added materials. We followed this in 1980 with three “expansions,” which was a concept almost unknown in the industry to that date. Unfortunately, the demand for new Star Fleet Battles materials quickly exceeded what could be properly tested and what could be made to work well inside the existing game system, and Star Fleet Battles began to pick up unpleasant nicknames such as “Errata Wars.” I responded by periodically producing entirely new editions of the game that incorporated all of the previous errata, addenda, updates, corrections, and so on.

Allen Eldridge and I increasingly disagreed as to the best way to run Task Force Games, wanting to pursue very different business models. In 1983, we decided to split the company in half. I took Star Fleet Battles to my new company, Amarillo Design Bureau. The two companies were “married” by a network of contracts, but relations between the companies varied over time from best buddies to barely speaking. During this time, the strategic (World War II in space) version of Star Fleet Battles—named Federation & Empire (1986) because I liked the Isaac Asimov book Foundation and Empire—came along, and with it I had the idea to brand the pair of games as the “Star Fleet Universe.” Over time, the universe came to include role-playing games (Prime Directive), card games (Star Fleet Missions, Star Fleet Battle Force), tactical ground combat (Star Fleet Marines), and more space tactical games (Federation Commander, A Call to Arms: Star Fleet, and the SFU version of Starmada). Also included was a line of miniatures.

A magazine, Captain’s Log, was created to support all of the games (new ships, weapons, and extensive tactics) and produced a considerable amount of fiction and background. Star Fleet Battles created the concept of players submitting “tactics articles” to advise other players how to win (and the entire Star Fleet Universe expanded that concept: every game has its own tactics forums). Captain’s Log always opens with a piece of fiction that becomes part of the history of the Star Fleet Universe. In the fiction, the reader discovers the background for various abstracted scenarios for the wargames.

By 1987, Paramount had finally noticed Task Force Games and its “sort-of Star Trek game” and, finding it legal, offered TFG a “sort-of Star Trek license” which remains in place today (and never expires). We got such a good license because Star Trek was effectively dead at that point, and the only new material being published was fan fiction and our games. We continued to expand the Star Fleet Universe. When Paramount started doing movies, we noted that there were some differences, and “canon Trek” and the Star Fleet Universe have continued to diverge. While canon Trek constantly updates and revises its technology, changing long-established principles, the Star Fleet Universe has remained very nearly consistent from 1979. We have a very different map from any of the several “canon” maps. Both canon Trek and SFU have added many new empires, none of which appear in both places (we have Lyrans, they have Cardassians). Canon Trek moved beyond “The Original Series” into new time periods eighty years later, but the Star Fleet Universe remained focused primarily on the twenty years after Jim Kirk romanced the women of the galaxy. Canon Trek has no drones, cloaked ships cannot use their shields, and the Romulans and Klingons use very different weapons than they do in the Star Fleet Universe. The Star Fleet Universe has fighters and carriers, and our gunboats are much larger than canon Trek’s runabouts.

Task Force changed owners in 1990 and again in 1994 (when another new SFB edition was released) and finally closed its doors in 1999. At that point, Amarillo Design Bureau incorporated, bought the license and all of TFG’s rights under the “marriage” contract, and became the publisher as well as the designer. The result was yet another edition of SFB and F&E, along with many other product lines for the Star Fleet Universe.

ADB has been in the forefront of social media such as Facebook and Twitter. We reach out to a broad audience, including Trekkers and cosplayers. Our audience includes all ethnic groups; it also spans the globe, with a sizable minority (five percent) not having English (American or British) as their native language. Women comprise five percent of the fans of our products. This is probably a reflection of the diversity of population found in the original source material.

Playing wargames allows players to understand that there are overall principles of tactics and technology that apply to every situation, in the real world or the many worlds of science fiction and fantasy. Probably the best line I ever wrote was that “wargames teach you to work together pleasantly with someone who is trying his best to kill you.”

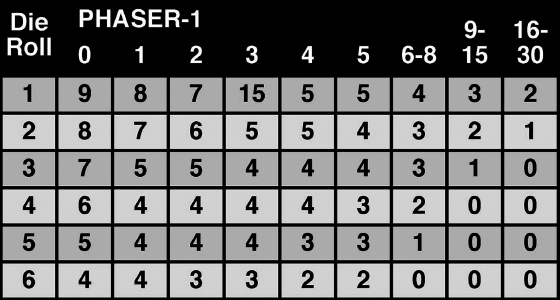

The basic concept was to “simulate” starship combat, not just do a spaceship game. Being a registered professional engineer and having also had advanced military training (as well as having read over a thousand history books), I knew how major military and mechanical systems worked. There was to be no “roll a die and move that many squares” in this design. While “luck” had a role in the game (since a die roll of 1 produced more damage than a die roll of 6) this was really not luck at all, just real-world statistics for the probability of a weapon striking a moving target at long range.

My designs reflected the Star Trek source material at every turn, even when the source material was contradictory or not based on reality. Doing the math based on the speed of light, the number of 10,000-kilometer hexes the ships are moving through, and the definition of “warp factor,” each turn in SFB represents an impossible 1/30 of a second, during which the ship can turn, fire weapons, load shuttlecraft, fight Marine boarding actions, and do no end of other things. While absurd from a technological point of view, this scale matched the action seen on television. Obviously, the television show was written based on dramatic effects and needs, and the game (intended for fans of the show who wanted to drive their own starships) had to reflect that. (Actual naval battles take far longer than a television audience will watch.)

Power was always a key element. The USS Enterprise generates thirty-six “points” of power: fifteen boxes each in the left and right warp engine, four boxes in the impulse engine, and two reactor boxes. It costs one point to move one hex, one point to fire a phaser, 1/5 of a point to operate a transporter, one point to keep the crew alive, two more to power the shields at basic levels, a point to run the targeting scanners, and so forth. There is never enough power to do everything, and a key element of gameplay is prioritizing what needs to be done. This mirrors the actions of starship captains on the screen, who were always giving orders like, “Divert power to shields.”

With virtually no hard data regarding the power of the weapons, I used my engineering skills to calculate the probability of a hit and the rate that the energy in a weapon would be lost over the distances involved. No element of the design was ever done for political or ideological reasons; everything was based purely on engineering and the need for good game design. We worked from the premise that if the game isn’t fun to play and doesn’t scare the players half to death, it won’t be successful.

Having studied aerial combat games such as Richthofen’s War, I knew that a critical element of the design was the ratio of how fast the ships could move versus how often (and how far) they could fire. If the ships moved too slowly (compared to rate of fire and range) the game would have no maneuver, only pounding on the enemy, which would require that weapons have lower hit probabilities. I went the other way, with ships that move about twice as far per turn as they can seriously hurt each other. (A typical World War II battleship could fire at least twenty times while covering the distance the shells fly.)

Seeking weapons had existed in Star Trek. For instance, the Romulans launched a seeking plasma torpedo at the USS Enterprise, and the ship survived only because the torpedo ran out of steam. That torpedo went into SFB, but we added more kinds and sizes of plasma torpedoes because the engineering design of the multitude of ships needed them. (Real world warships don’t all carry the same size of weapons.)

The semiofficial blueprints mentioned that the Klingon ships carried target-practice drones (never seen on any screen) that could be used to deliver nuclear warheads to the enemy. Drones of many types and sizes became elements of the game design and are used more to scare the enemy into or out of certain areas than to actually damage the target. Those same blueprints showed that the Klingon ship had a lot of phasers that it had never fired on television, so these became less efficient phaser-2s that were the same weapons as the Federation phaser-1s but had less accurate fire controls and a shorter range. The long-range photon torpedoes never required Captain Kirk to get in range of the Klingon phasers.

Geography drove the technology to some extent. Empires “west” of the Federation (Klingons, Kzintis) use drones and disruptors; empires “east” of the Federation (Romulans and Gorns) use plasma torpedoes. The Federation, in the center of the strategic map, uses the superb photon torpedo. Everybody uses phasers, which are the universal “gun” weapon.

Some non-television elements were added to the design to improve the game. Overloaded weapons (twice the power, twice the damage, limited range) were a non-television concept that I added to force combat to shorter ranges and keep the ships from endlessly poking at each other for hours without actually damaging each other. Shuttles were given a small phaser because without that, there was nothing for them to do. The phaser wasn’t enough, so later rules allowed shuttles to be loaded with energy and electronics (wild weasels) so they look to the stupid robot brain of a missile like the ship itself, to carry several drones (scatter-packs), and to deliver suicide bombs.

Star Fleet Battles is the ultimate in “complicated” games, with several hundred pages of rules and hundreds more pages of starship data, scenarios, and charts. Even so, there were several places where deliberate decisions were made to simplify concepts, physics, and rules; otherwise, the game mechanics would exceed what players will put up with. Moving targets are no harder to hit than motionless ones, and die roll modifiers to reflect if the target were moving toward you or across your front were rejected. Gravity has no effect unless you wander too near a black hole, and “orbiting” isn’t really done in a way that has anything to do with space satellites.

While television is simplified due to the time available to develop stories (e.g., Klingons are mean, move on) the entire Star Fleet Universe included extensive background, geography, and economics to show that even the bad guys had their warm sides and soft spots. The Klingons, being a military dictatorship, are mired in corruption. The Romulans are divided into “great houses” that combine aspects of megacorporations and political parties. The Gorn legislature never wants to spend money on the military. The Tholians are “reclusive” because they consider humans, Klingons, and Romulans to be little more than bacteria. Only a few Tholians arrived here from another galaxy, and they spend most of their time avoiding wars that they don’t have the strength to fight.

Star Fleet Battles, like some tactical games that appeared back in the 1970s, is a “scenario-based” game system. You have the rules, but you play specific scenarios, each of which defines the starting position of a set number of ships and their objectives for the battle. This is not a limiting factor, however, since the basic scenario can be adapted by players to use any ships they want, and the eight hundred published scenarios cover every imaginable military and political situation (but we keep finding new ones). You can rescue a freighter from a minefield, drive a monster away from a colony planet, or fight your way through the enemy fleet to destroy their supply base and force them to retreat.

As the game grew, I invented an alphanumeric rules system. Movement rules are “C,” while seeking weapons are “F,” and so forth. This allowed future expansions to add new rules to the appropriate chapter and kept all of the direct-fire weapons under “E” regardless of what product they were published in. Star Fleet Battles became the first wargame in which players were expected to cut their rulebooks apart and shuffle the pages from several products into one combined rulebook. This concept was continued into Federation & Empire and other games and was later copied by other companies, as, for example, in Advanced Squad Leader (1985).

The original game included individual ship diagrams; the weapons charts were in the rulebook. Players later showed me pages they had “taped together and photocopied” in which the ship was on the right half and all of the tables for its weapons were on the left. This concept was adopted immediately, and now more than three thousand ships are in the game. While television only showed cruisers, real navies have a myriad of larger and smaller ships, as well as older ships kept in service with refits, brand new ships just coming into service, and failed designs kept in service to get some value from the money wasted. With only so much budget, a navy must buy some small ships because there are so many small jobs that need doing.

Star Fleet Battles, like most wargames, is purely military (other than a few civilian ships used as targets in campaigns), but the whole point of a military is to protect the civilians who actually produce the money and develop the resources that pay for the military as a “necessary business expense.” The larger Star Fleet Universe (which includes many games reflecting the same database) includes RPGs that focus more on what the civilians are doing. The Star Fleet Universe, like Star Trek, prides itself on the diversity of its characters, with plenty of female and minority captains commanding its starships. (For that matter, plenty of women and young people are involved as staffers, playtesters, and players.)

Star Fleet Battles has published more player-created material (new ships, empires, weapons, scenarios, tactics, fiction, history, art, and no end of other things) than any other game system, and the other game systems of the Star Fleet Universe also publish extensive customer submissions. Some customers have designed entire products and gone on to open their own game publishing companies; Amarillo Design Bureau, Inc., prides itself on promoting creativity and rewards those outside designers who truly add something new and unique. This publishing philosophy has kept the players involved and the game system fresh, and is used in all of our product lines. Players are recognized for their contributions with not just the usual free copies and mentions in the books, but with medals and campaign ribbons posted on the company website.

Steve Cole, the president of Amarillo Design Bureau, Inc. (ADB) <www.StarFleetGames.com> has been around the wargame industry for a very long time. The son of a building contractor and a reserve engineer colonel, he studied engineering, graduating from Texas Tech in 1975. He played his first game (D-Day) at a church party in 1963 and published his first game (MP44) as part of JagdPanther magazine in 1973. He ran JagdPanther from 1973 to 1976, founded Task Force Games in 1979, then founded ADB in 1983. He has more than one hundred published game designs and has won three Origins Awards and a Gaming Genius Award. Best known as the designer of Star Fleet Battles, he would rather be known for other games he designed, most especially Prochorovka. He has designed tactical (Federation Commander) and strategic (Federation & Empire) board games, RPGs (GURPS Klingons), and card games (Star Fleet Battle Force). His book Running a Game Publishing Company is available for free at <www.starfleetgames.com/book>.