4. The Star

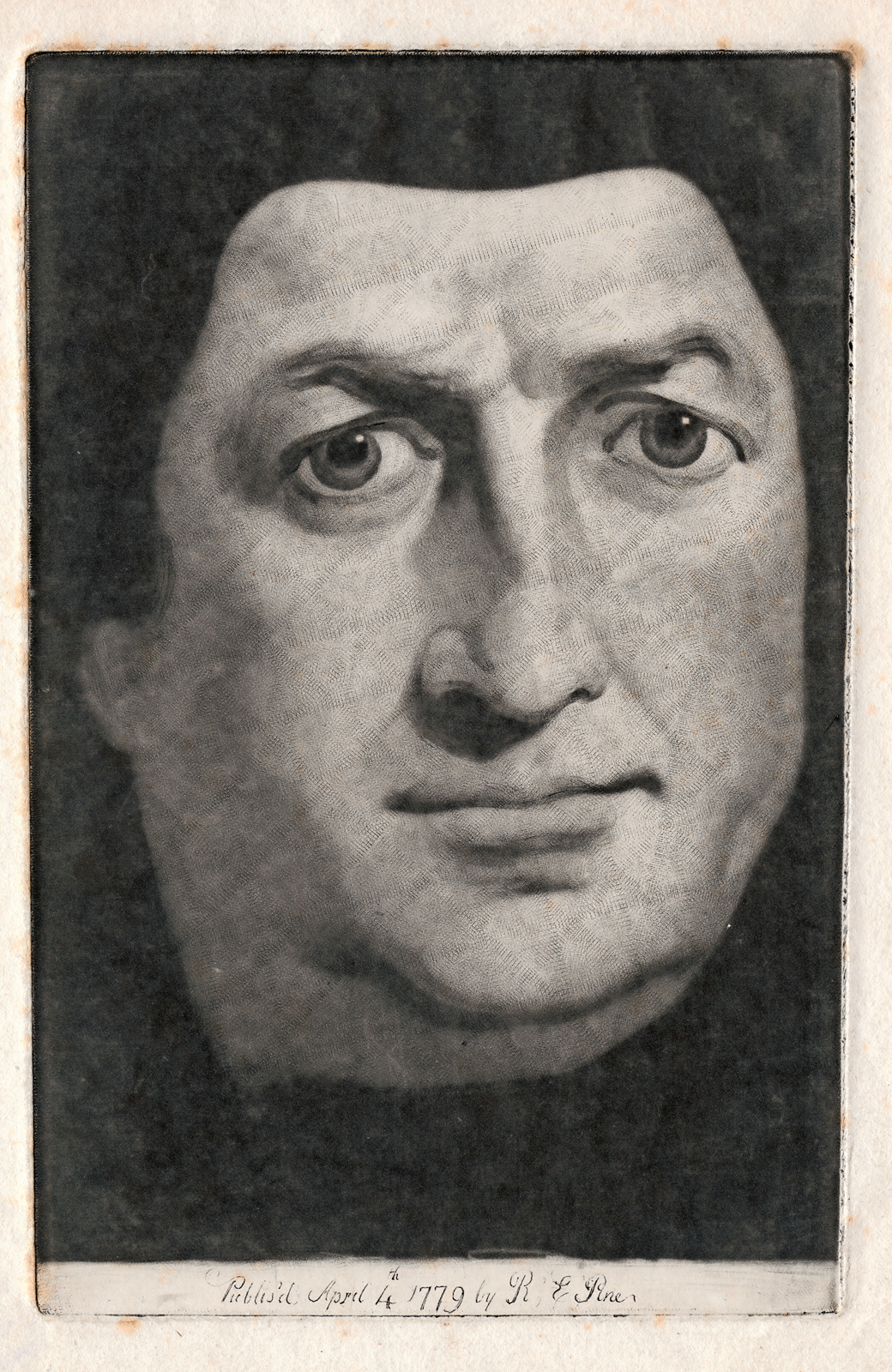

He was dead and yet very much alive; sleeping the endless sleep yet permanently wide awake. It was not just the enormous bull-like eyes which Robert Edge Pine (who had painted them four years before, when David Garrick was still living) now focused again on the beholder with the same fierce intensity which had made the actor famous; it was the brows above them, each doing their own independent thing; one more arched than the other. They were themselves a theatre company of two, those eyebrows: tragedy and comedy, sorrow and slapstick, dancing on the stage of his face. When Gainsborough complained that Garrick was his most difficult sitter, it was because those two wouldn’t keep still: ‘When he was sketching-in the eye-brows, and thought he had hit upon the precise situation, and looked a second time at his model, he found the eye-brows lifted up to the middle of his forehead, and when he a third time looked, they were dropped like a curtain close over the eyes, so flexible and universal was the countenance of this great player.’

Perhaps Pine’s head, floating in its dark eternity, was too uncanny for the multitudes of Garrickomanes collecting whatever memorabilia they could grab after his death in January 1779, for few copies of the mezzotint have survived. But England – and Europe, where he was also famous – was awash with Garrick memorabilia in every conceivable form. The invention of transfer printing in the late 1750s meant it was now a simple process to reproduce an image on the surfaces of ceramics and enamels. Now you could pour milk from a Liverpool creamware jug with Garrick’s face on it. Staffordshire pottery modelled Garricks in famous roles, Richard III especially, in the parlour; and, thanks to Thomas Frye, who was both painter and ceramicist, you could have your actor in Bow porcelain. If you wanted to furnish your house with Garrick you could upholster the chairs in cotton fabric roller-printed, in a choice of black or red, with Caroline Watson’s stipple engraving after another of Pine’s works, commemorating the Shakespeare Jubilee which the actor orchestrated at Stratford in September 1769. There he is, right arm extended, gesticulating at the statue of the Bard which had just been unveiled in the new Town Hall while reciting his grand Ode, composed for the occasion. Around him (as they were that rainy day in Stratford) were actors variously costumed as Falstaff, Lear and Macbeth. You could eat off Garrick plates; drink from Garrick-engraved rummers and goblets. If you couldn’t get enough of him, you might cover your walls with mezzotints of portraits of Garrick by Hogarth, Gainsborough, Reynolds; Garrick with Mrs Garrick; Zoffany’s pictures of him in his most celebrated roles: Abel Drugger in Ben Jonson’s The Alchemist; Hamlet in his ‘alteration’, of which not everyone approved; the skirted Sir John Brute in drag from Vanbrugh’s The Provok’d Wife.

David Garrick, after Robert Edge Pine, 1779

Or, after 1797, you could pay homage to Garrick in Poets’ Corner. In the spirit of not letting Garrick sink passively into the arms of death, the inspired memorial, commissioned from the sculptor Henry Webber by Garrick’s solicitor and friend Albany Wallis (whose teenage son had drowned in the Thames), has the actor parting stage curtains as if taking a final bow, posed between Comedy and Tragedy. There is a ponderously sententious inscription by the poet-actor Samuel Jackson Pratt, who, after a career of scandal (a pseudo-marriage) and stage flops, had written an orotund eulogy for Oliver Goldsmith and thereafter became England’s verse obituarist. The lines are taken from Pratt’s ‘monody’, composed at the time of the vast funeral arranged by Richard Brinsley Sheridan, more imposing than any given to defunct Hanoverian monarchs. Fifty mourning coaches processed from the Garrick house in the Adelphi to the Abbey, escorted by files of guards, mounted and on foot; while a crowd of fifty thousand watched the hearse pass on its carriage. As Garrick would certainly have wished, Pratt’s lines twinned him inseparably with the Bard, to whom he admitted he ‘owed everything’. ‘To paint fair Nature, by divine command, her magic pencil in his glowing hand, a Shakspeare [sic] rose, then to expand his fame wide o’er this “breathing world”, a Garrick came. Though sunk in death the forms the poet drew, the actor’s genius bade them breathe anew … Shakspeare & Garrick like twin stars shall shine, and earth irradiate with beam divine.’

Garrick’s Westminster memorial is directly in front of Shakespeare’s, which seems right, since it had all begun with the erection of the Bard’s own monument thirty-eight years earlier in 1741. As yet, the collection of monuments to genius was rudimentary and under-populated. Chaucer had been the first non-prince, non-aristocrat, non-ecclesiastic to be buried in the Abbey, but was laid there principally as Clerk of the Works. Francis Beaumont, Edmund Spenser and Ben Jonson had followed, the last with a terse inscription. As early as 1623, the year of the publication of the first Folio edition of the plays, one of Shakespeare’s eulogists had suggested that there ought to be a monument to the Bard in the Abbey, but Ben Jonson truculently resisted any such idea, declaring that ‘the man was the monument itself’. At the other end of the century, genius was admitted in the person of John Dryden in 1700, and then in 1727 Isaac Newton was given an immense and spectacular funeral before being laid in the nave.

Only when the grandiose and beautiful Shakespeare monument was set in the south transept in 1741 did that particular space turn into a mausoleum of genius, and one which, as in the case of the Bard, did not require any transfer of bones. It was none other than Cobham’s Cubs and the Stowe circle, together with Lord Burlington, who had created the Shakespeare bust for the Temple of Worthies six years before, who now raised subscriptions to make it happen. Alexander Pope, the poetical eulogist of Stowe, and the editor of a new six-volume Shakespeare, lent his efforts, as did Charles Fleetwood, the manager of Drury Lane, and one of his actors, Thomas King. William Kent, Cobham’s landscape architect, drafted the design for the memorial, and Peter Scheemakers sculpted a full-length figure, legs crossed, lost in compositional thought and leaning on a pile of books. The piece was as much a fanfare for British history as a monument to the country’s greatest writer. At Shakespeare’s feet are busts of three monarchs: Richard III, Elizabeth (for the obvious reason, but also for the less obvious of her personifying English resistance to ill-intentioned foreigners) and, as the memorial was conceived and unveiled in wartime, with Britain and France on opposite sides of the War of the Austrian Succession; hence the inclusion of the third monarch, Henry V.

The completion of the Shakespeare monument happened with enough fanfare to attract Garrick the Bardolater, then just twenty-four years old, a wholesale wine trader in London together with his brother Peter, but also an amateur actor and author of a popular entertainment, Lethe. Garrick would have had no difficulty in making the connection between Bardolatry and the drumbeat of national-imperial pride. He would go on to make an entire career out of beating that drum on both sides of the English Channel. Yet again, the epic of Protestant liberty had a lot to do with it. His grandfather David Garric was a Bordeaux Huguenot who had come to England when the rights of French Protestants were liquidated by Louis XIV’s revocation of the Edict of Nantes in 1685. Like Drake and Viscount Cobham, the Garricks knew who their enemy was. Years later, David the actor would take the fight over Shakespeare right to the doors of the Comédie-Française, which fell over him in belated adoration, much like Princess Katherine at the feet of Henry V. Garrick’s father, Peter, inevitably perhaps, joined the King’s army and became a recruiting officer in Tyrrell’s Irish Regiment, stationed for much of the boy’s childhood in the newly acquired fortress port of Gibraltar, the front-line rock abutting Spain.

Peter moved the family to Lichfield, in Staffordshire, where David went to the same school as Samuel Johnson, who was a few years his senior. He was already stage-struck when he moved to London to work with his brother in the wine trade. And because the Garricks supplied wine to the Bedford Coffee House round the corner from Covent Garden, the infatuation only grew stronger and deeper. It would be nice to think that, given his father’s occupation, he made a beeline for George Farquhar’s very funny comedy The Recruiting Officer, which had become a staple in the repertoire of Henry Giffard’s theatre out in Goodman’s Fields, Whitechapel. ‘Over the hills and far away. Over the Hills and O’er the Main/ To Flanders, Portugal and Spain/ The Queen commands and we’ll obey/ Over the hills and far away.’

Like all actor-managers, Giffard had had his ups and downs. The Licensing Act of 1737, which restricted performances to Drury Lane and Covent Garden, had closed his Whitechapel theatre (the second one in Goodman’s Fields) not long after he had built it. But palms were greased, approaches made, and in 1740 he was allowed to reopen. Garrick must already have known Giffard, since he had written Lethe, in which a predictable parade of fops and fools are offered the possibility of forgetting their life of troubles, for the manager’s benefit performance. While waiting for his Whitechapel theatre to reopen, Giffard toured East Anglia with a scratch company, and it was at Ipswich that the amateur thespian Garrick first tried out his art, billed as ‘Mr Lydall’. Giffard saw something out of the ordinary in the little fellow who could write, act and seemed to know enough of the bon ton already to be useful where it mattered. There was something brisk and vigorous about Garrick which Giffard recognized as theatrical fresh air.

On 19 October 1741, Garrick, all of twenty-four, appeared as the murderous monarch in The Life and Death of Richard the Third, sandwiched between a ‘Vocal and Instrumental Concert’, a dance act and ‘the Virgin Unmask’d’. The lead role was billed as being played by ‘[a] Gentleman who has never appeared on any stage’. So much for Ipswich.

The anonymity might have been Giffard’s attempt to pique curiosity, or even the habitual sadism of the audience, who, if things went badly wrong, would at least be entertained by a debacle: a stripling nobody biting off more than he could chew. They would pelt him with boos, hisses, choice abuse and solid objects. Or it is possible that Garrick chose anonymity because he had not yet decided whether he should go professional? The reception of his Richard made up his mind. On the following day, he wrote to his brother Peter that ‘my mind as you know has always been inclined to the stage.’ Though he expected Peter to be displeased with his decision:

yet I hope when You shall find that I may have ye genius of an Actor without ye Vices You will think less severe of Me and not be asham’d to own me for a Brother. Last Night I play’d Richard ye Third to ye Surprize of Every Body & as I shall make near three hundred pounds p[er]Annum by It & as it is really what I doat upon I am resolv’d to pursue it.

Garrick was right about his brother’s mortified embarrassment, even though the two of them had found it a struggle to make money in the wine business. Although some actors such as James Quin, Thomas King and Charles Macklin were well known to the public, acting was mostly considered an occupation rather than a profession, and a lowish one at that, somewhat akin to a fiddler or a barber surgeon. It was also notorious for its backstage promiscuousness. Worse still, actors seemed to indulge their notoriety in the full glare of Grub Street publicity without a second thought, as if it added to their reputation – which may indeed have been the case. One of the most complaisant and cynical, the actor and critic (itself a neat combination) Theophilus Cibber, countenanced a ménage à trois in Kensington, but only on the understanding that his wife’s lover would subsidize his stage performances.

What Garrick brought to the stage would transform all this. Although he had lived with the Irish actress Peg Woffington (who had earlier done a stint in a high-end brothel), he would end up an exemplary married man, his conjugal happiness represented in double portraits by Hogarth and Reynolds. More importantly, he would change what acting was supposed to be. Much later, the actor-playwright Richard Cumberland would remember seeing Garrick ‘come bounding’ on to the stage in 1746 in The Fair Penitent, ‘light and alive in every muscle and feature … it seemed as though a whole century had been stept over in the transition of a single scene.’ Alexander Pope was one of many of his contemporaries who thought that Garrick was the first to stake a claim for acting to be a true art.

London saw this right away. Garrick’s Goodman’s Fields Richard fell on the city like a clap of thunder. No one who saw his debut ever forgot it. Every coffee house and tavern talked of it. For a few nights, coaches clogged the streets of Whitechapel. The play was not Shakespeare’s original text but a cobbled-together amalgam of lines written by Theophilus Cibber’s father, the actor-manager Colley Cibber, together with chunks of Henry V, Henry VI and Richard III. But the great moments from Shakespeare, including many of the lines – the king’s haunting by the ghosts of his victims on the eve of the battle; and of course Bosworth itself, with the unhorsed king flailing his sword to the bitter end – were exploited for all they were worth. Audiences were accustomed to seeing the grand actors of the day declaim in a rhetorically lofty and mannered style. Most often, they did so with grandiose gesticulation, milking the pauses, investing speech with weighty gravitas. But instead of the usual crookback shuffle with the mouth-curling cackle-and-sneer, Garrick’s Gloucester appeared without any signs of the unhinged sociopath. Garrick prided himself on conveying the complexity of a character and on the ability to move from one state to another, both inwardly and outwardly. So the seductive Richard, the merry Richard, the twitching Richard and the monstrously brave Richard all appeared in their turn within the one frame, each convincing in their moment.

In 1745, the artist William Hogarth, himself on the way up, thought a picture should be made of Garrick’s Richard. It was a commission for a patron who wanted to preserve for posterity a record of the transformative power of the performance. Garrick was of course flattered by this, but he probably had something else in mind as well: the creation of a reputation through engraved versions of the painting. Hogarth, who came from a jobbing world of sign-engravers and satirical prints before making his own name with ‘Modern Morality Tales’ such as The Harlot’s Progress, immediately understood the value of this. But he was more ambitious. At heart he longed to become the great history painter Britain still wanted, especially in the time of its budding empire. The nearest thing was his father-in-law, Sir James Thornhill, who had provided ceremonious ceilings featuring William III and George I for the Royal Naval Hospital at Greenwich. To Thornhill’s horror, Hogarth had eloped with his daughter Jane. So the demonstration that Hogarth had all the qualities of an English Michelangelo was meant as an unapologetic assertion to both father-in-law and country.

In 1745, Britain needed history painting. The war with France had not gone as well as anticipated, and the Jacobite army of Charles Edward Stuart had got as far south as Derby. (Hogarth would also supply a picture of that shaky moment in a satiric rather than grandiose vein with The March to Finchley). But he seized the Garrick moment as an opportunity to bring the English back to their history with a vengeance and to do it on a heroic scale.

At over eight by three feet, the picture is big enough to deliver Garrick life-size into our presence, much as if we were sitting in the front row of the pit, or in a box close to the stage. Garrick’s haunted, terrified face is in ours. His gesticulating hand (a ring has slipped over the joint of a finger in his sweaty fear) presses against the picture plane. The tent – in fact the whole painting – as large as it is, feels claustrophobic, oppressive, the right sensation for Richard. Beyond, in the background, the fires of his and his adversary’s troops burn dimly as dawn comes up on his last bloody day.

Between them, Hogarth and Garrick had invented a completely new genre, hitherto unknown to any school of art: the theatrical portrait which at one and the same time delivered a likeness of the man (though in Garrick’s case it was said that it flattered him – as would generally be the case with stars) and a likeness of the performance. In its all-out rendering of the actor’s peerless ability to capture extreme passion – the talent for which he would become internationally famous – the picture was a textbook for future generations. With his Richard, and with the record of it, now reproduced in multiple prints, Garrick had fundamentally altered what true acting should aim for. Liberated from high academic style, it was free now to go after what he thought of as human truth written on the face and the body. Garrick would tell the aspiring actors who followed him that before all else they must study the part, make every line their own, inhabit, as we would say, the character; let it take full possession of them. He had also learned from Charles Macklin, who, when he was preparing Shylock, went to the length of going to see Sephardi Jews in London go about their business, that the book of nature written on the bodies and faces of contemporary humanity needed ceaseless study as well. Garrick’s instruction to fellow actors as well as himself was to lose one’s identity in the part. When he saw him do this in 1765, Friedrich Grimm commented on the ‘facility with which he abandons his own personality’.

Garrick was also familiar with the classic art literature on the affetti, the passions, especially Giambattista della Porta and the French painter and academician Charles Le Brun, both of whom had published what were in effect anatomies of the emotions: how they registered on the musculature of the face. How one mood succeeded another mattered to him, as he prided himself on letting the evolution of a character show through its many complicated modulations. (A favourite party trick was to sit wordlessly and let lust, terror, anguish and the rest follow each other on his mobile face.) This was especially true of his Macbeth, first played in 1744 and surprisingly accompanied by his writing a pre-emptive pamphlet attack on himself designed nonetheless for contrasts with his ponderous peers.

Garrick acted with all his body. He was no more than five foot four but the athletic force of his acting made him seem much bigger, as though his frame were built on springs. To the consternation of some other cast members, who liked to take things slowly, he was fast, vital, animated, nimble, almost like a dancer, darting from one spot to another. The envious Macklin said he was all ‘bustle bustle bustle’, but such was the energy that when a moment like Hamlet’s first sight of his ghostly father, or Macbeth’s of the dagger, required him to be absolutely stock-still, his immobility had a correspondingly electrifying effect. One admirer spoke of his own flesh creeping even before the Ghost was seen, though that may have had something to do with the little hydraulic device Garrick used in his wig to make the hairs stand on end. Garrick’s Richard was an immediate legend, talked about for years, becoming a staple of his repertoire, and the part (a little closer to the original folio text) which all great performers – Kemble, Kean, the American Edwin Forrest and his rival Macready – would feel in their turn that they must own.

Truth to human nature was not, of course, incompatible with making money. Hogarth and Garrick were perfect partners in their understanding of this brand-new commercial opportunity: the marketing of stardom. The Goodman’s Fields Richard would be engraved; the prints would make Garrick’s face famous; act as catnip for the box office; and in turn would generate a new cycle of demand to see him both live and preserved on paper. The star business had been born. In the first instance, Hogarth was responsible for the translation of his great Garrick–Richard into multiple prints, but he was not swift enough in delivering to satisfy his friend Garrick (who called him ‘Hogy’). Thereafter, especially once he had become partner-manager of Drury Lane, Garrick took control of his own publicity. In the 1750s he hired Benjamin Wilson, mostly a scene painter, to capture his most popular performances: Abel Drugger, Sir John Brute, Lear and Romeo, and the rest. The demand became inexhaustible. A stable of printmakers was assembled, many of them specialists in mezzotints, a relatively recent medium in which the plate was roughed up by the use of a toothed ‘rocker’, so that if printed at this point it would give a completely black page. The fully worked plate was then selectively scraped back and burnished to produce a whole world of tones, perfect for the picturing of dramatic scenes and expressive portraits. They could also be produced much more quickly, cheaply, and in a variety of formats to suit different pockets. James MacArdell, an Irish printmaker-portraitist with a shop in Covent Garden, was one of Garrick’s most reliable promotional printers, but demand was constantly outstripping supply and he worked with Edward Fisher and Richard Houston, and many others. By the time Garrick made his triumphal foray into Paris in 1764, his fame had travelled enough that he had to write to his brother George back in London for a speedy dispatch of prints to satisfy his admirers. The finer ones (often prints made after paintings by Reynolds and Gainsborough) he would personally supply to his notable fans; the rest went to market.

David Garrick was not just an actor superstar; he was also impresario, theatre manager, public relations man; image designer; discerning art collector, especially of Venetian paintings – Marco Ricci and Canaletto – and of Dutch pictures, which made him able to deal with artists on terms of mutual understanding. Garrick was as well a great bibliophile, bequeathing his priceless collection of 1,300 ‘Old Plays’ to the British Museum: the first great drama collection of its kind in the world. But Garrick was bookish in a modern way: perfectly in touch with shifts in public culture. From the 1750s, a cult of nature, of transparency and sincerity – the opposite of fashion, artifice and high manners – began to take hold in the pages of the first tear-soaked sentimental novels; in the freshening of landscapes; the recovery of original from corrupted texts; in the simplification of portrait style. Garrick’s antennae were acutely attuned to this alteration of sensibility, of which, in any case, he was an apostle. Sometimes, presenting himself as natural man was a half-truth. His acting style was natural only in contrast to the high rhetorical manner he replaced. His Shakespeare plays were often still ‘altered versions’, sometimes adapted by him so that Cordelia not only lives but is romanced by Edgar. A Midsummer Night’s Dream was turned into a musical entertainment called The Fairies. On the other hand, Garrick restored Polonius and Laertes, who had gone missing from previous performances of Hamlet, to their proper stature, though it took him only sixty lines to get from the death of Ophelia to the end of the play. In some ways, however, he was a true restorer of Macbeth in most of its Shakespearean integrity.

To record all this needed a better artist than Benjamin Wilson. Garrick told Hogarth that Wilson was not ‘an Accurate Observer of things, not Ev’n of those which concerned him’. He had given some theatre-scene subjects to his friend Francis Hayman, but it was in Wilson’s own studio, toiling away as the assistant given costumes to paint, that Hogarth had discovered someone who might be just that artist in the person of Johann Zoffany. Zoffany’s family origins were in Bohemia, though he had been born in Frankfurt and had come to London in 1760. Before plunging into the overpopulated world of jobbing art he had worked for a while as a decorator of clocks. His northern European, Dutch-influenced background had given him a talent for ‘conversation pieces’, the genre of informal scenes, multiple characters in a small format, which was perfect for rendering the kind of play-scenes Garrick needed. And there was something else as well that Garrick now had in mind as an extension of his fame: the opening of his personal and domestic life to the admiration of his followers.

Of course, the sex life of actors had been a staple of Grub Street printed gossip. But Garrick had a happy marriage and he had turned this unusual situation into another asset for the house brand. The story was the stuff of thespian romance. Eva Maria Veigel from Vienna, stage name Violette, fell for Garrick the moment she saw him on the boards; he couldn’t get enough of her dancing. She was a rose-cheeked Mitteleuropa blonde to his flashing, dark-eyed exuberance. Eva’s patroness, the Countess Burlington, thought Garrick beneath the dancing beauty who had performed before the courts of Europe, and attempted to break the romance, but amor vincit omnia and they were married in 1749. A few years later, Hogarth produced a double portrait of them which is one of the loveliest paintings he ever made. The actor is busy writing his Prologue to a play called Taste when he is playfully interrupted by his wife, flowers in her hair, aiming to snatch the quill from him. Garrick’s smile suggests he doesn’t mind the interruption a bit. It’s hard to imagine a sweeter evocation of the informality of a ‘companionate marriage’ – one rooted in love and friendship. And yet Garrick seems to have been unhappy with the Hogarth, especially the depiction of himself, enough at any rate to decline to accept it even after paying the painter his fifteen pounds. There are signs of a scratch through one of his eyes and, originally, a domestic setting. More than twenty years later Garrick tried again, this time commissioning Joshua Reynolds. Though the later picture keeps something of the gently humorous intimacy of the Hogarth, it is much grander. At the pinnacle of his career, only four years from retirement, Garrick has acquired some avoirdupois along with his international fame, even while Eva, wearing a queenly concoction of silvery silk, lace and muslin, has become more spare. Set in their garden beneath a romantic sky, Garrick has been reading to his wife. But Reynolds has posed him with the book still open, a thumb marking his spot; the actor has lowered it to gaze at his wife. Instead of returning the gaze she is caught lost in thought, though the thought could as easily be: ‘How long this time?’

David Garrick and Eva Maria Garrick, by Sir Joshua Reynolds, 1772–3

The garden was by the Thames at Hampton. But its riverside lawn was inconveniently divided from the Palladian villa by the road to Hampton Court Palace. What to do? A bridge would have displeased the neighbours, who included the likes of Horace Walpole, so Garrick had a tunnel built under the road. In 1762, eight years after acquiring the villa, he asked Zoffany to come for a weekend and paint husband, wife and company. Wilson, who thought of himself as Zoffany’s mentor as well as his employer, was livid at the thought of being displaced by his own junior and told Garrick so. Garrick put on one of his broadest epistolary smiles and disingenuously told the affronted Wilson not to trouble himself with trifles. But the truth is that Zoffany quickly became the engine of Garrick’s promotional machine. At Hampton he rose to the occasion with a pair of graceful conversation pieces showing the home life of the Famous Man. Together they are also the first painted idyll of the English weekend: tea out of doors by the river, the King Charles spaniels flopped on the grass; a discreet servant, Charles Hart, ready to pour; a family friend, Colonel George Boden, making himself at home; and Garrick himself gesturing and speaking to brother George, who is fishing but has turned to hear what David has to say. You can smell lawn, river and cake, and everything smells good. Its pair has Eva leaning on the shoulder of her husband in front of the little Palladian octagonal shrine with its Ionic columns he had built in 1757 for his alter ego Shakespeare. Just visible through the door is the centrepiece, a statue of the Bard commissioned from Louis-François Roubiliac, another London Huguenot, who charged Garrick a huge sum (either three hundred or five hundred pounds, depending on the source). But nothing was too good for Shakespeare. The temple to the Bard housed sacred objects: a chair made from what was said to be Shakespeare’s own mulberry tree, and other treasures. And at the foot of the little flight of steps in Zoffany’s picture is a boot scraper. Woe betide those who might desecrate the shrine of the immortal with riverside mud or the droppings of animals!

The obsession never faded. In 1768, the empire was at its Georgian zenith. Britain had taken possession of French Canada and French India; it was awash in wealth from the sugar and slave economy of the Atlantic and, if there had been unfortunate riots in the American colonies over the Stamp Act, those disagreeable troubles seemed to have receded. The mood was triumphal self-admiration, not least for the greatest writer the world had ever seen. In that same year, the Stratford Town Council wrote to Garrick asking him if he could find a way to contribute a statue or a painting for their new Town Hall. In return they offered him the Freedom of the Town. Flattered, Garrick, who had had Gainsborough paint him leaning on a column with his arm around Shakespeare’s bust, the Bard seemingly inclining his head towards his champion as if recognizing their kinship, seized the opportunity. A colossal multimedia production would be mounted in September of the following year. There would be fireworks, a performance of Thomas Arne’s Judith (perhaps because of the name of Shakespeare’s daughter); a horse race; a custom-built rotunda for a great orchestra; a recitation by Garrick of a Jubilee Ode he would compose; and a parade of the most celebrated Shakespearean characters in costume, though no actual plays. But even David Garrick could not control the English weather. Torrential rain crashed down on Stratford. The Avon burst its banks; the horse race and the fireworks were cancelled; and people sloshed around in the muddy rotunda where Garrick still performed as best he could his great Ode. He was not to be defeated, however. Back in London he devised a theatre version of the Jubilee, increasing the size of the orchestra and the massiveness of its sound, and with characters from nineteen scenes distributed around the space. It, too, was multimedia; an immense hit running to ninety performances. Against the derision poured on the Stratford event along with the downpour, Garrick, as usual, had the last laugh.

In 1776 he took his last bow, declaring with immense emotion, and aware of the ambiguity, that ‘this is an awful moment for me.’ For his final performance he played one of the crowd pleasers, the young Felix in Mrs Centlivre’s Wonder. But that same year he also came back to Lear, and this time dressed the cast not in the usual Georgian dress but something thought to correspond to the ancient British. Antiquarian history was then in style, including books about costume. When the mad old King was reunited with Cordelia, tears flowed freely down Garrick’s big face. But then the audience had also noticed wet cheeks in scenes with Goneril and Regan, both from the daughters and their father. The later eighteenth century was in fact the golden age of crying, the surrender to the promptings of the heart. Garrick’s waterworks that night were copious. He claimed that he owed his famous version of Lear to having personally known a man who had killed his daughter by dropping her from a window and then spent the rest of his mad life endlessly repeating the action, his face wet with tears. But at that particular moment David Garrick hardly had to act at all.