4. Chummies

1843, Edinburgh. The Old Town is hungry. The tenements growl with want. Even pease and oats and smokies cost the pennies many don’t have. Men are idle all over Scotland; tens of thousands of them without work in Paisley alone. Every morning sees lines of the scrawny and the desperate; hollow-eyed men and women, bairns with legs like pipe stems, curved and brittle, queue up at the workhouse doors, frantic to be let in. Hunger lands like a flapping crow on the streets of Newcastle, York, Manchester, Leeds, Birmingham, Bristol, London, pecking at the poor. The Old Town brims with them, since the better-off sort moved to New Town. The cobbled backstreets beneath the castle and all about are full of families whose grandpas had been cleared from the highlands and islands, and who now kept body and soul together by working at looms that are stopped with the disruption in trade.

But that is not the Disruption on everyone’s tongue and mind. That Disruption is an argument, become a schism, in the Church of Scotland. The cause was the right claimed by lairds and baillies, landlords and other owners of livings, to appoint ministers. That right had gone uncontested, but now brave, fierce voices spoke out against it, saying there should be no such property rights in the Church; that it was in fact an outrage against its holiness. Such was the anger of Dr Thomas Chalmers and many more who had come to be so persuaded that they would not abide any longer in a Church which countenanced such infamy. At the opening of the General Assembly, the Moderator himself read a statement to that effect, whereupon some four hundred fellow ministers rose from their benches and, like the Covenanters before (though with less hurling of chairs), broke the cowardly decorum. Out into the streets of Edinburgh they marched, three abreast, a river of black-clad righteous indignation, and down to old Tanfield Hall, where they signed a solemn ‘Act of Demission’: their statement of departure from their livings in the enslaved Kirk and arrival into the new Free Church of Scotland which was to be their state of proper grace. It was no light matter that they were embarked upon. They were now cast out, along with their families, from what had sustained them in soul and, of more immediate importance, in body, too, submitting themselves to the judgement of the Lord, who, they prayed, would look with kindness on their act of self-cleansing, as He had with the prophets of Israel and the Saviour Himself.

Watching all this was the painter David Octavius Hill. His own speciality was landscapes, plain and fresh and simple; the cool light of Caledonia. But Hill, in his early forties, was profoundly stirred; so moved that he wished to capture the moment of Demission in some great painting that would in generations to come be spoken of in the same breath as The School of Athens or The Night Watch. But in the same instant that he decided the rebirth of Christian Scotland must be his life’s mission, he realized how daunting was such a task: hundreds of likenesses. To pick and choose among them, moreover, was to act in express violation of the very principles of freedom and brotherhood that had motivated the dissenters in the first place. The impossibility of the work lay upon him like a millstone, even as he began to sketch the more prominent godly heroes – Dr Chalmers, above all.

An answer was at hand. One of Hill’s friends was Sir David Brewster, the eminent physicist of St Salvator’s College at St Andrews, to many a fearsome figure who was likely to greet even the most innocuous approach with a scowl or an entirely unprovoked tirade, to the consternation of those who had innocently inquired the time of day or some such. But speak of matters optical, and Sir David’s fearsome face would glow with friendly light. Lately, he found nothing more engaging than the endeavours of his good friend Henry Fox Talbot to reproduce images from exposure to sunlight on paper treated with silver nitrate; a process he had made known to the world four years before, in 1839. This was the very same year in which a rival pioneer, Louis Daguerre, had shown his own photographic images, registered on individual copper plates, to the immense wonder of the public, and the art world in particular. The daguerreotypes were exceptionally beautiful but could not be multiply reproduced. Fox Talbot’s paper negatives could generate a wealth of prints but, beside Daguerre’s beautifully fixed details, they seemed primitive and blurry. Moreover, to obtain any image at all required an unconscionable length of time, the intervals of suitable light in Britain being unpredictable. Just lately, however, to Brewster’s intense fascination, his friend in Wiltshire had altered his procedure in a manner that had the potential to make paper negatives superior in every way. Instead of waiting the hours required for an image to appear on the treated paper, Fox Talbot immersed the latent, immanent image in a bath of gallic acid, from which – eureka! – a fine image was developed with astounding expeditiousness. Its quality was strong enough for the name Fox Talbot gave it – ‘calotype’; ‘beautiful picture’ – to be no vain boast.

Ever practical, it occurred to Sir David that his friend Hill’s dilemma in making his great, monumental, vastly populated history painting might itself be expedited were Hill to avail himself of photographs of the Demissioners, especially since, before long, they would all disperse to whence they came to start new livings as ministers of the Free Church. Such photographic ‘sketches’, which would take a trifle of the time needed for formal drawings, could then be reassembled and composed for Hill’s grand picture. Moreover, Brewster suggested someone who might provide immediate practical help. One of his colleagues at St Andrews, Dr John Adamson, a fine and famed chemist, had himself become knowledgeable in the process of making calotypes. Some of striking quality had already been made of various (gloomy) buildings of St Andrews – this in the last years before its renaissance as the cradle of golf. In turn, John Adamson had introduced his younger brother Robert, also a chemist, albeit a novice, to the mysteries of this miraculous new craft or, might one say … art? Should Hill find the proposal agreeable, Robert might come to Edinburgh and, together, they would see if calotypes of the ministers might be achieved. And who knows what else? Other events worth fixing in silver nitrate? The building of the Scott Monument by their friend George Meikle Kemp; the families of their heroes, Burns and Sir Walter; topographical views of the city itself with some of the more respectable of its citizens gathered beneath the walls of the castle, or on Princes Street?

Robert Adamson was just twenty-one in 1843. He had the makings of another great Scottish engineer: the impassioned curiosity in things mechanical and structural; a fine, strong, analytical mind. But what he did not have was the physical constitution for a strenuous life spent amidst fire and iron. The silent solemnities of calotypography on the other hand, the alchemical appearance of images, was Adamson’s modern epiphany. When he came to Edinburgh, he and Hill immediately struck up one of the great partnerships in British history: the painterly spark and the scientific alembic; the eye for humanity and the mind to make such a picture stick. But the truth is that the Hill–Adamson partnership would not have produced the astoundingly beautiful work without each having a portion of the other’s talents.

They set about their task. Church ministers posed. Chalmers himself was photographed in a classic attitude of his preaching, one arm stretched high in emphatic gesture; so high, and for all the relative speed with which the image was taken, long enough for the doctor to need his arm supported by a brace set in the wall. Pictures of animated discussions were taken. It was all working. Others sat for them: George Meikle Kemp, along with his laboriously progressing Gothic monument to Sir Walter Scott; a portrait of David Octavius Hill himself, handsome and affable; more dramatically, the blind Irish harpist Patrick Byrne, who had come to Edinburgh that summer and whose romantic performances had caused almost as much of a sensation as the Disruption itself; Hugh Miller, like Meikle a self-taught prodigy, stonemason turned geologist, author of The Old Red Sandstone, arguing, notwithstanding his evangelical Christianity, that the earth was of immense antiquity and had been home to innumerable now-extinct species.

Miller was photographed in the great cemetery on Calton Hill, where the unbelieving David Hume had been laid to rest, and Hill moved into Rock House, just opposite. He and Adamson together were moved by the marriage of antiquity and modernity, past and present, which was the profound reality of their contemporary Scotland; humming with innovation and experiment, as it had been for a century, and yet so richly clad in memories both painful and glorious.

Much of what they saw in the Edinburgh of the 1840s displeased and disturbed them: the slums and rookeries of the Old Town, sweating with disease and grim destitution; children with misshapen bodies; drunks and whores, thieves and scoundrels. But they would not be like Friedrich Engels in Manchester, or Mrs Gaskell, committing their minds and their art to the graphic illustration of all this squalor and despair: the victims of the industrial maw; devoured and spat out again as the cycle of trade dictated. Instead, the two of them decided they would picture an alternative world of work; a place which carried on much as it had for centuries.

The Adamsons had in fact already made at least one calotype of the desolate-looking harbour of St Andrews, with fisherfolk near their boats. But there was somewhere much closer by, just half a mile or so from Calton Hill, that offered a much more picturesque possibility: Newhaven. Living and working where they did, Hill and Adamson could hardly have avoided the Newhaven fishwives, lugging their enormous hundredweight baskets, full of haddock, herring, cod and oysters, up the hill and down into the city every single day: an enormous feat of strength. Even from inside Rock House they would have heard the cry of ‘Coller, haddie!’ from the young women, dressed in their striped yellow-and-blue skirts, bulked up with so many petticoats as nearly to double the weight of their burden.

There had already been some discussion as to whether the answer to the ills of industrial cities was somehow to reinvent the village: the kind of communities from which the Clearances had banished shepherds and crofters. In those villages, had there not been broadly extended families, lending support to each other in hard times? Had there not been a strong and benevolent Church to contain and correct the iniquities which tempted the impoverished?

In 1819, Thomas Chalmers, who would become the moderator of the Free Church, had actually undertaken an experiment in social reconstruction along these lines in one of the poorest districts of Glasgow. Excluding conventional poor relief and its overseers, he instituted an independent system of pastoral care run by deacons and elders who sought to recreate the microworld of neighbourly mutual support they imagined had existed before the coming of machine-age slums. In the same spirit, another friend of David Octavius Hill, Dr George Bell, went so far as to champion the restoration of urban smallhold farming on city wasteland (a programme that has re-emerged in some of the devastated districts of rustbelt America today).

With the best will in the world, though, the chances of this kind of benevolent social engineering were always going to be slim in the heartland of industrializing Scotland. But when Hill and Adamson went to look at Newhaven, they thought they had found a place miraculously spared the grinding destructions, moral and social, of the industrial world. The truth was that, while no paradise of ease, Newhaven was bound to prosper as long as the great city half a mile away went through a population boom. Edinburgh needed daily fish; a lot of it. The ‘Small Line’ of the shallow waters carried long nets with thousands of hooks to catch codling, haddock and whiting, while the ‘Great Line’ in the deeps went after cod, mackerel and the great herring shoals. To catch that last treasure, the Newhaven fleet went 200 miles north twice a year, close to Wick, many of their women going with them as gutters and smokers. There were dangers. Prolonged foul weather could play havoc with the small boats, destroy them altogether. In those bad times men would be lost and prices go up. From the changed cry they heard on Calton Hill, Hill and Adamson titled one of their pictures ‘It’s No Fish Ye’re Buying, It’s Men’s Lives’. There were too many orphans in Newhaven. The photographers caught one of them, a small boy, wearing his dead father’s trousers, many sizes too big for him, held up by precarious braces; an image of immense poignancy. That one they called ‘His Faither’s Breeks’.

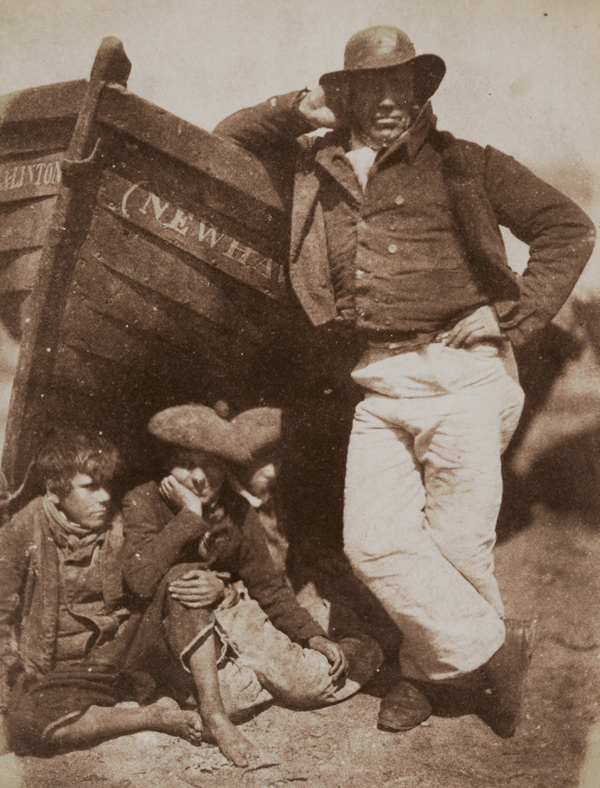

When a father like Sandy Linton leans on his boat, his three bare-footed fledgling boys sitting under the bow, one of them grinning for the camera, the other two indifferent, father-and-son bravura mixes uneasily with the sense of precariousness that must have stirred every time the small boats sailed off into the rough night.

Fishermen Ashore (Alexander Rutherford, William Ramsay, John Liston), by David Octavius Hill and Robert Adamson, 1843–8

The authenticity of the pictures comes, first of all, from the strong impression that it is the fisherfolk, of both sexes and all ages, who control the poses, and with as firm a hand as they set about their livelihoods. Some of them evidently enjoyed mugging for the camera; others challenged it. John Liston, one of three fishermen leaning in a comradely way on each other, strikes an attitude of top-hatted sauciness, one dirty-trousered leg crossed over the other; while the body language of the stern Alexander Rutherford is all crossed arms and confrontational stare.

But without much of his help, preoccupied as John’s brother Willie was, cleaning the line with the sharp edge of mussel shells, Hill and Adamson nonetheless turn him into one of the more romantic heroes in nineteenth-century art: the shadow from the brim of his hat falling over the brow of his handsome face; his clothes worn with a good-looking man’s air of confidence – the knotted kerchief, the soft coat and waistcoat with its double row of buttons. No image – certainly no painting of the nineteenth century – turns the self-contained reserve of strength and patience of the working man into a thing of beauty as much as this single calotype.

Willie Liston, by David Octavius Hill and Robert Adamson, 1843–8

It is not, however, the men of Newhaven who take centre stage in Hill and Adamson’s calotypes. The men were gone fishing at night and, in the early hours, needed sleep when on shore, and back again they went, so many of the images caught by the photographers were cautiously sought and perhaps grudgingly allowed. Very quickly Hill and Adamson saw who were the true anchors of the community: the women. Their non-stop work, cleaning and mending nets, gutting and curing fish, hauling the catch to the city, taking care of the bairns, was unremitting. Fanny Kemble, the actress who played Edinburgh often and knew both David Octavius Hill and the fisherfolk, wrote that ‘it always seemed to me that the women had about as equal a share of the labor of life as the most zealous champion of the rights of her sex could desire.’ When disaster befell one of them, or merely hard times, they could turn to one another. They called this sisterhood – ‘chummies’ – a bottomless well of succour, support and gossipy entertainment. No painter of the time caught working women in all their rough and comely humanity with as much richness as the chemist and the painter with their camera. Millet turned his peasant women into clod-like monuments; Degas made his working dancers and prostitutes objects of the sweaty ogle; as for their British counterparts, their women were either personifications of moral positions, theatrical histrionics or erotic fixations.

Like the painters, Hill and Adamson train their eyes and their lens on the young women. The occasional widow and matriarch appear, listening to James Fairbairn, the visiting pastor, or enthroned before a pilot’s door. But it is the girls who take centre stage in so many of the photographs: captured in the full beauty of their unconcern with the photographers and their light box. One of them, a genuine beauty, Jeanie Wilson, appears over and again, all the more mesmerizing because of her absorption in her work. The two girls, Jeanie Wilson and Annie Linton, are to be taken as they are, with their little row of herring and oysters, entirely in each other’s close company, and not ours. Even when she was obliging Hill and Adamson with some sort of pose, Jeanie had other things to think about. In another picture she appears with her sleeves rolled up, leaning on her sister’s shoulder, hand on hip, not to please the men looking at her either, eyes staring down. It’s been another long day. Sometimes, too, the chummies won’t stand still for the cameramen; they stand in a lane teasingly, some bare-footed, some not; backlit and blurred, some holding a wee bairn: the sisterhood in its flower. Of the five girls in another chummy shot, only one is bothering to acknowledge the camera, and she is not especially friendly towards it. In yet another heart-rending photo of a young mother with her small child, the image is shaky, as if the mother was rocking her wee one, or as if Hill and Adamson themselves were unresolved about intruding indecently into her fragile life.

Jeanie Wilson and Annie Linton, by David Octavius Hill and Robert Adamson, 1843–8

It was striking, too, that when The Fishermen and Women of the Firth of Forth was published as an album – of the poor, but not for them, since the album, especially when combined with Hill and Adamson’s architectural photographs, was pricey – it was the women who attracted particular attention. Dr John Brown, a friend of Hill and the reviewer for the Free Church paper, the Witness, praised the ‘wonderful’ pictures to the sky, especially ‘these clean, sonsy, caller, comely substantial fishwives … as easy, as unconfined, as deep-bosomed and ample, as any Grecian matron’. But one of the most vocal champions of the calotypes and the women they portrayed was Elizabeth Rigby, who herself had sat for Hill and Adamson at Rock House. Rigby was English, given the German education the most ambitious parents then supplied for their gifted children, and had come to Edinburgh with her widowed mother, Anne, in 1842, a year before Robert Adamson. But she quickly became a fixture of the city’s culture as essayist and critic, and would go on with her friend Anna Jameson (also photographed by Hill and Adamson) to be one of the most eloquent and influential voices in British art writing. Though she often shockingly lauded the pleasures of being unmarried, in 1849, a year after Robert Adamson’s untimely death, Elizabeth did indeed marry, Charles Eastlake, a painter and critic who, with a knighthood under his belt, became President of the Royal Academy, President of the Royal Photographic Society and, in 1855, Director of the National Gallery. Two years later, Elizabeth Eastlake become immensely influential in her own right, and wrote a famous essay on photography, which, depressingly, given her earlier enthusiasm for Hill and Adamson’s great work, now demoted it to the status of a visual record of fact, doing the documentary work true art ought to disdain. That was certainly not how she had felt ten years earlier in Scotland.

Fisherwomen (A Lane in Newhaven), by David Octavius Hill and Robert Adamson, 1843–8

Fisher Lassies (Grace Ramsay and Four Unknown Fisherwomen), by David Octavius Hill and Robert Adamson, 1843–8

Fisher Lassie and Child, by David Octavius Hill and Robert Adamson, 1843–8

By this time, David Octavius Hill, bereft by the premature death of his partner Adamson, had given up photography altogether. Many followed, with ambitions to capture the social reality of Victorian towns, but never with quite the innocent eye and candid roughness the two men had brought to the fishing village on the Firth of Forth. Instead, Hill continued to toil on with the work which had started it all – the vast canvas commemorating the Disruption, which turned into an ossified monster of overpopulation. But a year before Lady Eastlake produced her thoughts on the relationship between art and photography, another of their sitters at Rock House, Anna Jameson, who had become the indispensable authority on the art collections of Europe and author of the first generation of guidebooks to European museums, published her Communion of Labour, celebrating what she described as the union of ‘love and labour’ which nonetheless endured amongst women in unpromising institutions such as prisons and workhouses. Perhaps Jameson remembered the fishwives of Newhaven more sympathetically than Lady Eastlake, or at least saw that photography, when not made condescendingly, might be a friend to the cause of women, at least when it was women who were taking the pictures.

Anna Brownell Jameson, by David Octavius Hill and Robert Adamson, 1843–8

Christina Livingston was not by any means the first professional woman photographer in Britain. Julia Margaret Cameron had become justly famous for belying Elizabeth Eastlake’s pessimism, taking photo-portraiture not just to the level of paintings but beyond it in imaginative expression. Clementina, Lady Hawarden, though not strictly a professional, had used herself and her daughters for a series of mesmerizing experiments in the way women saw each other and themselves, often in the mirror, sometimes in each other’s eyes, games and interrogations as brave and deep as anything put on the page by Virginia Woolf.

This was not Christina’s world, Christina’s mind or Christina’s work. But like Cameron and Clementina Hawarden, she was a pioneer nonetheless, the first British woman to become a press photographer, and she did it, moreover, because she had to. She was a lowland Scot, daughter of a bootmaker who had moved to Chelsea to make his name and fortune. At twenty-seven, she married Albert Broom, an ironmonger, but it was when his business collapsed in 1903 that the forty-year-old wife and mother borrowed a box camera and began another life entirely. Apart from a sharp eye for opportunity, Christina had the business head in the family, taking pictures of royal household guards with enough skill and friendliness that she became part of local life around Buckingham Palace, enough at any rate to open a stall selling postcards and cheap prints of her pictures to the public. She was, in fact, the first vendor specializing in this kind of British ‘tourist’ photo, graduating to become the official photographer of the Oxford and Cambridge Boat Race; of the Household Division of Guards; and fashionable and ceremonious horseracing events. King Edward VII and the Queen knew about ‘Mrs Albert Broom’, as she called herself professionally after her husband died in 1912.

By this time Christina had developed an entirely different line of subjects: the suffragettes. In May 1909, a Women’s Exhibition was held at the Prince’s Skating Rink in Knightsbridge, a cavernous, 250-foot-long space. Ostensibly (and deliberately) the exhibition seemed just to be the mother of all village fetes – a showcase of all the usual work with which women were traditionally associated: baked goods and confectionery, cakes and sweets; embroidery, hats and flower-arranging. But though she was the photographer of such occasions, this would not have drawn Christina Broom to take her pictures of the show. As a news photographer, she had already taken fine shots of a suffragette march from the Embankment to the Albert Hall in June 1908, and now, a year later, Christina knew that the Women’s Exhibition was a turning point in British history. The organizer of the exhibition was the Women’s Social and Political Union (WSPU), and it was being held as a fund-raiser. Each of the fifty stalls had committed to provide not less than a hundred pounds’ worth of goods, and in the end the show raised five thousand pounds for the cause which Emmeline Pankhurst (the subject of one of Christina’s most beautiful portraits) described in her introductory brochure as ‘the most wonderful movement the world has ever seen, a movement to set free that half of the human race that has always been in bondage and to give women the power to work out their own salvation in the political, social and industrial spheres’.

The Women’s Exhibition, by Christina Broom, 1909

By the spring of 1909, both Emmeline and her daughter Christabel (also beautifully and informally photographed by Christina) had been to prison for disrupting Liberal party political meetings. All the same, it was surprising to find among the stalls selling suffragette ribbons and badges in their colours (white for purity, purple for imperial dignity, green for hope) a replica of a prison cell, designed to show the discrimination and degradation to which women were subjected even when they were behind bars. Around the mock-cell were lines of Edwardian women in their flamboyant hats waiting to get their tour and talk from suffragettes who had had personal experience.

Emmeline Pankhurst, by Christina Broom, 1910s

It was a tricky moment for Christina. She had a living to earn in the world of men; indeed, with the royals and the trousered powerful. But she was also obviously a whole-hearted sympathizer. In 1910, she was the photographer who captured the great march through London, culminating in a mass rally in Hyde Park. She photographed the Pankhursts and their leading comrades – Emily Wilding Davison, who would die under the hoofs of the royal horse at the 1913 Derby; Kitty Marion, the actress, who became the most dangerously militant of them all. For the last time, Christina was able to take photographs which portrayed the suffragettes as intent only on peaceful demonstrations for their cause.

Suffragette March in Hyde Park (Emmeline Pethick-Lawrence, Christabel Pankhurst, Sylvia Pankhurst and Emily Davison), by Christina Broom, 1910

After the 1910 elections, however, this changed. The Pankhursts and their sister comrades were regularly imprisoned and, when they embarked on hunger strikes, brutally force-fed. A ‘Cat and Mouse’ Act allowed the government to release the hunger strikers for as long as it took for them to recover physically, before re-incarcerating them. Faced with this more systematic oppression, the WSPU itself took a much more aggressive turn, which went from suicide and self-sacrificial tactics to a campaign of harm to others. Arson was the weapon of choice, but the chosen venues were extremely dangerous. In 1912, Mary Leigh, Gladys Evans, Lizzie Baker and Mabel Capper attempted to burn down the Theatre Royal in Dublin during a packed matinee performance, hiding canisters of gunpowder close to the stage and hurling petrol and lit matches at the combustibles. The principal target was the Prime Minister, Herbert Asquith, who was present and who that same morning had had a hatchet thrown at him by another suffragette. Postal incendiaries took a similarly lethal turn when phosphorus was thrown into pillar boxes with the intention of burning postmen picking up the mail, and in at least three cases succeeding. Any institution which the WSPU identified as speciously sacred to the official and especially male world was fair game. The tea pavilion and the tropical orchid house at Kew were bombed; another bomb was discovered in the nick of time outside the Bank of England; still another went off at the Royal Astronomical Observatory in Edinburgh. The bomb set at the Lyceum Theatre in Taunton was painted with the slogans ‘VOTES FOR WOMEN’, ‘JUDGES BEWARE!’ and ‘MARTYRS OF THE LAW’.

Christina Broom stopped taking photographs of the suffragettes. But someone else was. In 1913, the Home Secretary, Reginald McKenna, purchased, for the sum of seven pounds six shillings and eleven pence, for his department an eleven-inch Ross telecentric lens, the first long-distance lens to be made in Britain, patented just a year before. A high-level joint meeting of the Metropolitan Police and the Home Office held in the spring of 1912 had decided that, since the WSPU had become a terror organization, some sort of pre-emptive surveillance was required to avert threats to the kind of public institutions they seemed to be favouring. A photo dossier, the first such security surveillance file, was to be compiled while the women were in prison and thus captive subjects. It was assumed, of course, that none of the suffragettes was likely to oblige the photographers by remaining still enough for their image to be taken. Some contorted their face in a grimace, hoping to make the picture useless as an identity record. Initial efforts to take mug shots met with similar futility. One remarkable print was doctored so that the policeman’s arm gripping the recalcitrant suffragette Evelyn Manesta in a neck hold showed instead nothing more threatening than a scarf.

Hence the Ross lens. Outside Holloway Prison, the Home Office photographer hired for this secret surveillance, a Mr A. Barrett, would wait in an enclosed car until the opportunity arose for him to take pictures of women exercising in the prison yard. Little by little, this photo-surveillance file of the ‘Wildcats’, as the militant suffragettes were called in the code the authorities now used, grew. Copies were distributed to institutions deemed under threat, such as the Tower of London, where the Jewel House had been attacked.

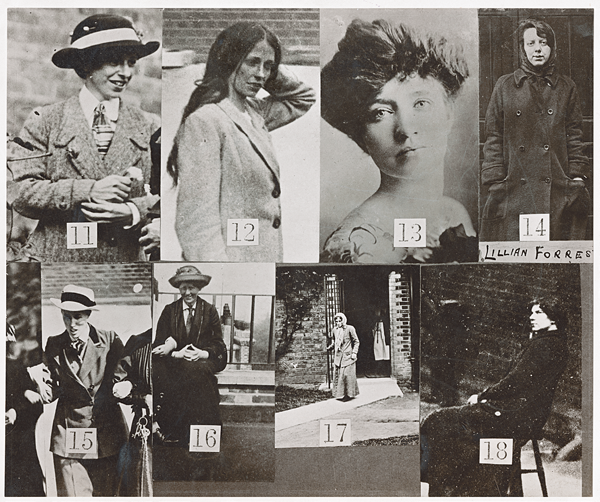

Surveillance Photographs of Militant Suffragettes (Margaret Scott, Olive Leared, Margaret McFarlane, Mary Wyan, Annie Bell, Jane Short, Gertrude Mary Ansell, Maud Brindley, Verity Oates, Evelyn Manesta), by unknown photographer, Criminal Record Office, 1914

Surveillance Photographs of Militant Suffragettes (Mary Raleigh Richardson, Lilian Lenton, Kitty Marion, Lillian Forrester, Miss Johansen, Clara Giveen, Jennie Baines, Miriam Pratt), by unknown photographer, Criminal Record Office, 1914

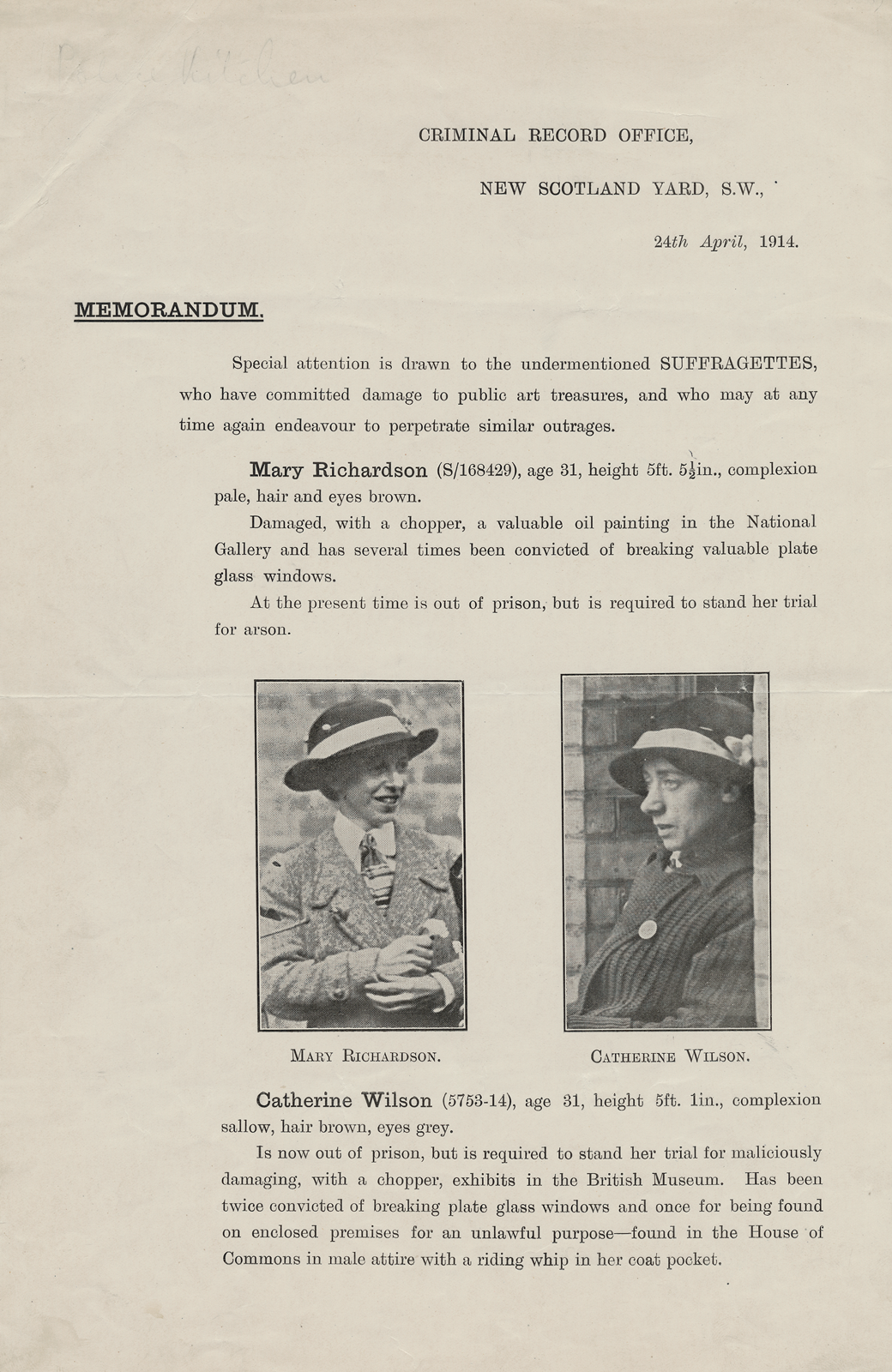

Prime among the new range of targets were London’s public art galleries. The fact that they were often full of nudes, which, the suffragettes reasoned, had largely been created by men for the pleasure of their own sex, and that this drooling exploitation masqueraded fraudulently under the guise of appeals to Imperishable Beauty, gave the new attacks a certain logic. Kitty Marion, who owed at least part of her success to just this kind of ogling, later wrote in her autobiography that ‘I was becoming more and more disgusted with the struggle for existence on commercial terms of sex … I gritted my teeth and determined that somehow I would fight this vile economic and sex domination over women.’ That connoisseurs often seemed to consider paintings and statues of women as more precious than the actual things only added fuel to the fire. At her trial for taking an axe to Velázquez’s Rokeby Venus in the National Gallery in March 1914, Mary Richardson justified her vandalism by saying, ‘I have tried to destroy the picture of the most beautiful woman in mythological history as a protest against the Government for destroying Mrs Pankhurst, who is the most beautiful character in modern history. Justice is an element of beauty as much as colour and outline on canvas.’

The police and the Home Office had already decided at their 1912 summit that museum guards ought to be supplemented by plain-clothes police mingling with the public. But neither this tactic nor the distribution of photo files to the museums managed to prevent a rash of attacks on works of art, some of them chosen arbitrarily or, like the Giovanni Bellinis at the National Gallery and an Egyptian mummy in the British Museum, for reasons that were not articulated. Possibly, Herkomer’s portrait of the Duke of Wellington in Manchester was chosen for the Iron Duke’s reputation as a male hero (since much of his unstoppable womanizing was less known), but John Singer Sargent’s portrait of Henry James was a more baffling pick, given the writer’s well-known support for women’s rights.

Mary Raleigh Richardson and Catherine Wilson, by unknown photographer, Criminal Record Office, 1914

For a while, the threat to art was such that both the British Museum and the National Gallery closed their doors. This left the National Portrait Gallery, now at the bottom of St Martin’s Lane, as the beneficiary of a thwarted museum-going public. Its staff had already been issued with a batch of photos of the likeliest suspects which they were supposed to consult when alerted to suspicious behaviour. On 16 July 1914, one the guards wondered about a woman who seemed unusually preoccupied with Sir John Everett Millais’ portrait of Thomas Carlyle. After the event, he would say that he did wonder about this but decided the woman’s close inspection of the work meant that she must be an American. When she returned the next day he changed his mind about this, since no American, he remarked, would have paid the sixpenny entrance fee two days in a row.

Quite what her attentiveness betokened, though, the guard did not stop to ask himself. He would soon find out when Margaret Gibb, calling herself by the alias of Anne Hunt, took a meat cleaver from inside her blouse, smashed through the glass covering the painting, cutting herself quite badly as she did so, and mutilated the hated face from brow to beard. She stopped only when a female art student who had been sketching in the gallery wrestled her to the ground while help was summoned. At her court appearance the next day, blood from her wound ‘dripping down the side of the dock’, as the Daily Telegraph was thrilled to report, Margaret/Anne explained very much in the Mary Richardson manner that ‘life’ was altogether more precious than art, since you could always get other works of art but the lives of women like Mrs Pankhurst, slowly being snuffed out in prison, could not be replaced.

Nineteen days earlier, an Austrian archduke and his wife had been shot in Sarajevo. Two weeks after Margaret/Anne’s court appearance, the world was at war. The WSPU suspended their campaign for its duration, hoping that the act of loyalty would be recognized by the long-overdue granting of the vote. It was, albeit not until 1928, and then incompletely.

Now, Mrs Albert Broom had another subject. The Irish and Scots Guards she had photographed had changed their dress uniforms for khaki and she pictured them as they went off to Flanders with smiles on their faces. When the Prince of Wales visited the 3rd Battalion of the Grenadier Guards at their training camp on Wimbledon Common, she was to take that picture, too. ‘Goodbye-ee, goodbye-ee/ Wipe the tear, baby dear, from your eye-ee.’ She went to see the ranks. One of her most heartbreaking photos is of the Bermondsey B’hoys, one of the Pals cohorts, friends and neighbours who were kept together in companies attached, in this case, to the Grenadiers. And when the wounded started to come back to Blighty and were treated to tea by the King and Queen at Buckingham Palace in March 1916, there of course was Christina, taking shots down the long tables, the men all with medals dangling from their necks, the bandages around their heads gleaming white.

Edward, Prince of Wales, by Christina Broom, 1914

Cheeeese. They are doing their best to smile for Mrs Albert Broom. But not many of them are.

Are we downhearted? NO!