THE THREE TREASURES

|

THE THREE TREASURES |

The Three Treasures in their most basic definitions represent the primal and accumulated energies of the body (ching), breath (qi), and mind (shen)—both in the physical connotations and in the spiritual sense. To understand these three energies, you must first know the important role played by “before heaven qi” (hsien t’ien qi) and “after heaven qi” (hou t’ien qi).

Before heaven qi is the quality and quantity, so to speak, of these three energies inherited from our ancestors and parents. After heaven qi is what we accumulate from our own efforts. So we might say that people who abuse their bodies their whole lives but live a long time have a lot of before heaven qi. Whereas people who are sickly in their youth have inherited very little. However, these same sickly people who engage in the arts of nourishing life practices can accumulate enough after heaven qi to live long, healthy lives.

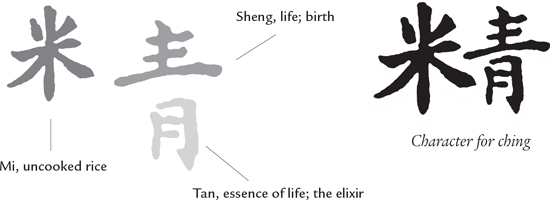

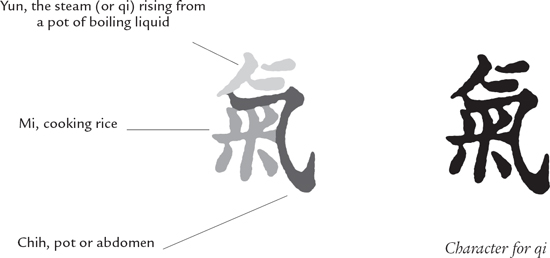

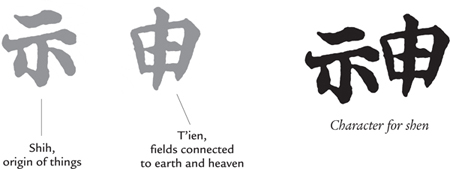

In order to understand the meaning and function of the Three Treasures, it helps to first examine the actual Chinese characters for ching, qi, and shen and to know why the Taoists elected to incorporate them.

The character for ching is comprised of the main radical mi, which symbolizes uncooked rice. It also contains the radical sheng, which holds the meanings of life and birth. Lastly, the radical tan is employed, meaning the essence of life. The symbol for tan carries the idea of the hue of a plant just sprouting—the white, green, and yellow hues that first burst forth. This idea is equated with the essence of life itself and is thereby extended to that of elixir.

The ideogram for qi depicts rice (mi) being cooked. Above the pot we see yun, which depicts the vapors coming off the top of the pot. The radical chih represents the pot in which the rice is cooked, or the abdomen in which the liquid (blood) is heated. The vapors coming off the pot are qi as an energy. They can also be viewed as clouds (earth’s steam). Our breath serves not only as a process for sustaining life (as cooking is to eating) but as a catalyst for producing energy (as cooking produces steam). In representing qi as vapor or steam—which drives pistons in powerful engines—this ideogram clearly symbolizes the energy and power of qi.

The character for shen is made up of shih, which means the origin or highest order of things. In brief, it depicts those things coming from heaven—the sun, moon, and stars. Next to it we see t’ien, which depicts a field, or paddy. The vertical line running through it symbolizes the connection of heaven and earth. The implied meaning here is the origin of things (shih) that connects people to heaven and earth and that is found in the fields from which sustenance is got. People can connect themselves to physical fields, human fields, and heavenly (spiritual) fields.

In light of these three characters, the meaning of the term tan t’ien (referring to the lower abdominal region) can be grasped. Tan means elixir and, as stated, t’ien means field or paddy. It is within the very emptiness of our abdomen that tan t’ien exists. It is where we become spiritually pregnant and give birth to our spirit child—our restored youthfulness.

Tan t’ien is the spiritual equivalent of the fetus inside a woman’s uterus, of raw rice being cooked in a pot, of ore being smelted inside a furnace, but most significantly, it is the place where ching and qi unite and create the spiritual embryo; it is the place where qi, our spiritual food, is cooked and where we refine raw essences into pure essences. The analogies are seemingly endless, but the idea is always the same: refinement of our natural life essences—ching, qi, and shen.

Ching

Ching

Taoists call the regenerative force in human beings ching, and they equate it with the body’s physical strength and vitality. Ching is by definition sexual energy, sexual secretions, blood, food, and saliva. The arts of nourishing life methods sought to restore ching to its condition in a person’s childhood. Ching is the body’s natural life energy and is acquired through nourishment and is dissipated through exertion, both physical and mental.

Ching can be thought of as containing three distinct physical aspects: 1) sexual secretions; 2) blood and the nutrients within it; and 3) flesh and bone. It is easy to understand not only the interconnection of each aspect but also the reliance of each on the other. Without sexual secretions we could not have a body in which blood nourishes flesh and bone.

As a goal, Taoists seek to restore the ching to its pure state, before masturbation ever took place, before sexual thoughts dominated our thought processes, and before anxiety took its toll on our lives. In part, it is the conservation of sexual secretions that restores and nourishes the blood. This restored blood, additionally nourished by proper diet and herbal medicines, and stimulated by the breath exercises, can then transform ching into its true or refined state.

Ching is also equated with the very force that drives us to procreate. Even though this energy can be very strong, Taoists do not view it as beneficial. Certain sects of Taoism, however, have mistakenly thought that restoring youthful vigor and the drive for sexual prowess were in themselves the restoration of ching. This erroneous belief entirely misses the point. That type of sexual energy is associated with fire (destructive) and creates the need for dissipation. Those who follow such methods get caught in a vicious circle of forever restoring and dissipating, which has nothing to do with forging the elixir.

It is because of such practices and misguided beliefs that competent teachers are such a necessity. A good teacher can supervise students so that they don’t get caught up in this newfound sexual energy and end up destroying not only their ching but their qi and shen as well. These energies are interdependent, and if one is injured, they all suffer. Sexual prowess is not what the legitimate Taoist seeks; rather, it is sexual energy. The achievement of immortality comes through the forging and refining of the Three Treasures, not their dissipation.

Taoists understand quite clearly that it is because of sexual dissipation that we are in this world. Likewise it is the dissipation of ching that will cause our departure from the world. It is thus evident that if we conserve and nourish our ching, life itself can be preserved.

The immediate goal is to reach that state of both physical vitality and mental purity that we had as children. This does not mean that you immediately enforce celibacy upon yourself. “Natural celibacy,” however, is the answer. Accomplished over time through the adherence of regulating body, breath, and mind, natural celibacy, the point where sexual desire just fades away and is no longer thought about, is achieved not by design but by the natural process of rejuvenation.

True restoration of ching is purely a benefit of someone who is focused on regulating the body; celibacy is by extension a result of the natural course of events. When the ching is restored, the notion of dissipation is feared, just as the notion of celibacy is feared by someone attached to sexual activity. No one should just jump into celibacy (which rarely produces the proper results anyway) and think that the problem will be solved. On the contrary, it will just create more problems, just as jumping into dual sexual-cultivation (Taoist practices in which men and women engage in sexual acts in order to form the elixir of immortality) will also create many problems.

An old story tells about a man who visits a Taoist mountain hermitage and becomes curious as to the comings and goings of the monks. He observes that the younger monks descend the mountain every month or so for a few days and assumes they fetch supplies in the town below. The middle-aged monks, he notices, descend about every six months. The elder monks and the three children who live there under their care never leave the mountain, even though the elders walk as spryly and with as much stamina as the children.

One evening at dinner, the man presents this observation to an elder monk, who responded as follows:

The younger monks indeed fetch supplies, but also go to visit the ‘flower girls’ in town. They are still young and find celibacy too demanding and obstructive to their practices, so they need to dissipate every couple of months. Otherwise, sexual desire might dominate their thoughts and thus destroy their practice.

The middle-aged monks descend to take care of monastic business in town, but also on occasion to take advantage of the flower girls’ favors, as every now and then the need for sex arises, but for them it is much less often than for the younger monks.

We elders live in repose from the duties of fetching supplies and business dealings. Besides, the walk is no longer worth the favors of the flower girls. Our minds are in keeping with the children, the only difference is that we elders are free of sexual attachment and the children not yet captured by it, but in the end it is the same.

Ching is restored, replenished, and accumulated by regulating the body through the practices of fasting, ingesting herbs, maintaining a certain diet, and exercises. These practices are aimed at restoring youth, vigor, strength, and stamina.

When we were young, we could seemingly play forever and never run out of energy. A day was an eternity when we were having fun. Summer vacation from school was beyond even the idea of an eternity. Time itself seemed slower in our youth. But as we grew older and had to deal with fear, anxiety, responsibility, sex, and so on, time also grew shorter with each passing year. In our adulthood, years and months race by like days, and days like minutes, rushing us faster and faster toward death. Taoists observed this passage of time and knew instinctively that a child’s state of mind was far superior and more beneficial than an adult’s. This is why the language of Taoism is filled with ideas and statements expressed, in English, with terms that begin with the prefix re- (restore, rejuvenate, regenerate, revert, regain, retain, return, refine, and so on). Taoism is forever referring to the “pliability of a child,” as Lao-tzu called it.

Qi

Qi (breath) is rather complex, so it is difficult to provide a simple definition. Nonetheless, in regard to the arts of nourishing life, the basis for regulating the breath, we breathe in “primal breath” (yuan qi) from the atmosphere that in turn nourishes our “proper breath” (cheng qi). The more deeply and longer the breath can be held, the more primal breath is absorbed into the body, which then develops the “true breath” (chen qi). True breath is generated by and from the lower abdomen. With this true breath the blood can be properly stimulated to circulate throughout the body, thus creating breath flow (yun qi). From this derives what is called “internal breath” (nei qi), which is the energy felt moving about the meridians and the source of heat felt in the body and its cavities. In other words, internal breath is the result of the proper practice of the arts of nourishing life or, more precisely, regulation of the breath (t’iao hsi).

Qi

Primal breath is the energy that permeates all things in the universe. It is what animates life and all substances. We breathe in this primal breath from the oxygen around us. The more primal breath that is absorbed into our bodies, the greater our level of spiritual attainment, physical and mental strength, and our ability to achieve longevity and immortality. So when the Taoists say, “sink the breath into the lower abdomen,” they are speaking directly about the ability to absorb primal breath into the lower abdomen.

Proper breath is what nourishes our blood and body in normal daily life. This breath can be regulated to stimulate qi to a certain extent, but it can only provide short-term health benefits. It is not the qi used in forming the elixir of immortality. However, it is the qi used in external qigong—such as for breaking bricks—and through its development it can be transformed into true breath. True breath is the breath that permeates every element of the body. This is what Chuang-tzu meant by “a true man breathes through his heels.” In the case of proper breath, the breath is manipulated physically by the expansion and contraction of the abdomen and lungs. But true breath is driven by primal breath and is felt throughout the entire body. As an analogy, this is much like Lao-tzu’s statement, “breathe like a bellows”; there is no place within the bellows that does not receive air. Experiencing this breath is unlike any other sensation of breathing. It is as if the entire body begins breathing in a very expansive, lively, and full manner, and yet it does so of its own accord. The body feels light, nimble, and active. Many practitioners can experience this early on in their practice, but it usually occurs sporadically because the mental intention (called i in Chinese) is not yet strong enough.

I

True breathing comes not from pushing out the stomach and filling it with air, rather from focusing your attention and allowing the breath to follow mental intention. Anyone can accomplish this. Just close your eyes momentarily and focus your attention on your lower abdomen. Within moments you will feel the breath activated there. From this seemingly simple effort comes a wide range of qi development and experience. In Pao-p’u-tzu, Ko Hung states:

Man exists within his breath, and breath is within man. Throughout Heaven, Earth, and the ten thousand things there is nothing which does not require breath to live. The man who knows how to circulate his breath can guard his own person and banish any evil which would attack him.

Numerous books, from those dealing with yoga and martial arts to those dealing with healing and meditation, have been written on the subject of breathing. It is rare, however, to find one that speaks about how the breath can really become natural and effective. Mostly these books speak about slowing the breath, making it deep, long, continuous, and even. Anyone who tries this soon discovers that the breath rises into the solar plexus and lung area and becomes short, tense, and unnatural. This happens because the breath is being forced to do something that it does not do naturally.

The breath has a rhythm of its own that should be allowed to slow down and become deep through the influence of the practice, not immediately and forcibly made to be slow and deep.

Another problem with the breath stems from how the abdomen itself is thought to function. Most people think that just pushing out the front of the abdomen is somehow abdominal breathing. This is only half breathing. The abdomen should be thought of as a balloon or bellows, with the entire area breathing, not just the front part.

Trying to make your breath slow, deep, continuous, and even is like stirring up a dirty glass of water to get the debris to settle; it will just continue to be muddled and agitated. If, however, the glass were set aside and left alone, the debris would settle to the bottom of the glass of its own accord.

As stated in the Mental elucidation of the thirteen kinetic postures (a t’ai chi ch’uan treatise attributed to the immortal ancestor Wang Chung-yueh):

If you give all your attention to your intent [i] and ignore your breath [qi], your strength will be like pure steel. If, however, you only pay attention to the breath, the blood circulation will be obstructed and your strength weakened.

All you need to do in applying intent is to focus your attention on the lower abdomen (or whatever area you are working with) and the breath will follow. Sense and feel the area with all your attention. From this practice your breathing will naturally become slow, deep, continuous, and even because you are not trying to make it so; the breath is just acting in accord with the intent. This is truly “sinking the qi into the lower abdomen.” Breath is like the debris in the glass of water; if you leave it alone, it will sink.

Another manner of explaining true breath is to refer to the idea of refinement. Breath that is concentrated low in the abdomen warms the blood, and blood that is warm circulates more completely. This warm blood then travels through the arteries in all the muscles of the body, and likewise is transported into all the veins that enter into all the sinews and tendons that surround the bones. From here the increased circulation and supply of blood reach not only the skin but actual bone through the capillaries. All the muscles, tendons, sinews, and skin are nourished by this warm blood. But more importantly, this warmed blood contains qi and enters the bone, turning it to marrow. When this occurs, the body again feels light, nimble, and active. This process restores the body, flesh, and bones to the pliability of a child’s.

Another view of this is simply that the abdomen represents a cooking pot. Taoists clearly understood that the human body is made up mostly of fluids—water, blood, secretions, and so on—and fluids become stagnant unless mobilized. Water can be mobilized by heat, such as when it is boiled. Likewise, blood can be mobilized if heated. Taoists also understood that the breath is hot, and they associated it with fire. We blow on our cold hands to warm them, knowing the breath is hot. To a Taoist, then, the human body is like a large pot filled with water, and the breath is like the fire under the pot.

The abdomen contains bodily fluids, just as a cooking pot contains water. When the water is heated, it begins to move just as our blood moves when warmed and the breath is properly activated. Boiling water produces steam, just as our warmed blood produces qi. Into the water we place the uncooked (and thus inedible) rice so that we can eat it when it congeals into cooked rice. We likewise concentrate our breath on the lower abdomen, or, viewed in another way, on what can be called the emptiness of our abdomen. When the qi circulates (as in the cooking of rice), it congeals in the lower abdomen (thus making the rice edible) and is made functional.

This association of fire and water with abdominal breathing in Taoist practices is very important. When Taoists speak of fire and water (hou shui), they are referring to this process of breath heating and stimulating the ching (in the sense of blood). Achieving this important process is the purpose of all internal work.

Fire

This process of regulating the breath can be further compared to the refinement of ore into pure steel. The abdomen can be likened to the furnace; breathing to the bellows; qi to heat; and ching to ore. The more that ore is refined by blasting in the furnace, the more it can progress through the stages of turning into iron, iron into steel, and steel into pure steel. Ore turned into iron can be seen as the process of refining ching, iron turned into steel as the process of refining qi, and steel turned into pure steel as the process of refining shen.

But by definition, qi can also be associated with just about everything animate and inanimate. For example, the qi developed in martial arts to protect the body from injury is called defensive qi (wei qi). The qi derived from eating food for nourishment is called nourishment qi (ku qi). The qi inherited from your parents is called before heaven qi, and the qi you acquire from the arts of nourishing life practices is called after heaven qi. Indeed, even the weather is called heaven’s qi (t’ien qi). All things in the universe have qi, from rocks to human beings. These different types of qi can be defined in terms of ten categories, three subtle and seven coarse, also referred to as the three heavenly spirits and the seven earthly spirits. The three subtle categories comprise the positive qi (ching, qi, and shen) and the seven coarse (seven emotions or passions) include the negative qi (happiness, joy, anger, grief, love, hatred, and desire).

Water

It is clear how extensively the concept of qi runs in Chinese thought. Qi is far more than just a latent energy abiding in the body. It encompasses all things in the universe, from stars to the tiniest dust motes.

Shen

Shen (spirit) manifests itself through intent. Only when the ching and qi have united can there be shen. It is shen that forges the mixture of ching and qi into the elixir, or that moves the ching and qi in Nine Revolutions, whereby a drop of pure spirit (these revolutions purify and forge the essences of ching, qi, and shen into an elixir, a pill, or a seedlike substance) can be deposited into the lower abdomen (Field of Elixir). This is why the use of intent is so important in connection with leading the breath. Shen is not just the mind or intention, no more than qi is just breathing or ching is just blood circulation. Just as water can be transformed into steam, intent can stimulate the breath to transform it into qi and blood into ching. Shen can then transform this mixture (ching and qi) into the elixir.

The T’ai Chi Ch’uan Classic, attributed to the Sung dynasty (A.D. 960 to A.D. 1126) Taoist immortal Chang San-feng, states, “The mind is the chief, the qi is the banner, and the blood is the troops.” In the old days of warring in China, the chief would position himself on a hill to oversee the entire battlefield. When he wanted to send his troops to a certain location, he would first send his banner man there. Upon seeing the banner, the troops would mobilize and go immediately to that place. This is likewise a description of what is called moving the qi. Using mental intention, one sends the qi to the location of an injury, and the blood (ching) then follows. When qi and ching have congealed to undertake the task of healing the injury, we can say that shen has manifested.

So, just as we can express our ching externally through numerous manners of physical exertion, the qi can also be expressed externally through different means. The shen, most powerful of all, can also be expressed externally in countless ways. This state of external expression is called spirit illumination (shen ming), and it means that the spirit can function and be utilized as readily as the body.

The very heart of this practice is to create a spiritual embryo in which the ching and qi can be thought of as the egg and sperm; intent brings about the spiritual intercourse, and finally the child, shen. The lower abdomen is the womb. Although the analogies used to explain ching, qi, and shen might lead to the idea that they are mental phenomena, they are indeed real physical phenomena, brought about through practice. Moreover, ching, qi, and shen are interdependent. When one becomes strengthened, the others benefit as well. When one is weakened, the others are likewise weakened. For this reason, a person needs to regulate the body, breath, and mind. Heaven has its three treasures: sun, moon, and stars. Earth has water, fire, and air. Human beings have ching, qi, and shen.

In each case, all three aspects must be kept in harmony for existence to be maintained. To see that this is true, all we need do is imagine what would happen to the heavens if the sun were to disappear, or to the earth if water were to vanish, or to a human being if he or she were to stop breathing. In all three cases, losing any one of the essential treasures would bring disaster to the whole. When our ching is depleted, the breath (qi) can function no more, and so the shen dissipates.

One of the rulers of the Shang dynasty (circa 1766 B.C. to 1154 B.C.) had engraved into all the imperial bathtubs, “Renew yourself every day completely, make yourself new daily, still anew today, and every day anew.”