LI CHING-YUN’S INTRODUCTION TO THE ORIGINAL TEXT OF THE EIGHT BROCADES

|

LI CHING-YUN’S INTRODUCTION TO THE ORIGINAL TEXT OF THE EIGHT BROCADES |

A translation of Li Ching-yun’s introduction to the Eight Brocades follows, interspersed with my comments and translation of the original text of the Eight Brocades.

The Methods of the Eight Diagram Active Kung

I call these methods active kung. My teacher handed down these exercises to me as the Methods of the Eight Diagram Active Kung.

Author’s Comments

Active kung (hsing kung) is a fairly common term found in qigong, meditation, and martial arts Chinese texts. Normally it is translated simply as “exercises.” The term hsing can mean “activity” or “practice”; kung translates as “skill,” “work,” or “effort.” This kung is the same as in kung fu. However, the Taoist meaning of hsing kung is closer to the idea of “practicing yoga.” The reason that the term Eight Diagram (pa kua) is used here can be assumed to have been in order to establish a correlation with the I Ching Eight Diagram theory. However, the problem is that Li Ching-yun does not attempt any effort at explaining these correlations. Maybe his teacher related them to him, but Li did not share them in his lectures.

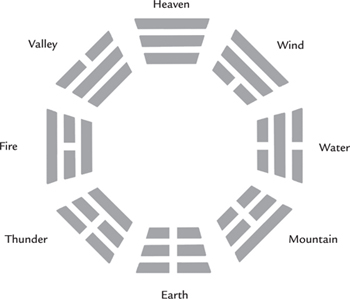

The first emperor of China, Fu Hsi, supposedly invented the Eight Diagrams during the legendary period of the Age of the Five Rulers, approximately 3000 B.C. The Eight Diagrams are composed of eight sets of three straight- or broken-lined images that represent our phenomenal world. These eight three-lined images are the very basis on which yin yang theory is founded, with the yang forces represented by solid lines and the yin forces by broken ones. In a vision, Fu Hsi saw the Eight Diagrams on the back of a tortoise shell. From these eight images, he divined and perceived the natural changes occurring in the world. Later, other emperors, for purposes of divination, would drill holes into tortoise shells, burn them, and then, by the cracks produced, determine the images pertinent to their questions. Dried bones of dead animals were also used for these purposes.

Over the course of China’s history, these eight images developed into an entire system of divination and philosophy. Other than the Five Activities (wu hsing) theories, nothing has been more important to the early Chinese mind than the Eight Diagrams. If a philosophy, health practice, martial art, or medical theory cannot be equated with or validated by the Eight Diagrams or Five Activities, it really has little worth in the Chinese mind.1

During the Chou dynasty (1122 B.C. to 255 B.C.), King Wen stacked the Eight Diagrams on top of each other to create the sixty-four six-lined images, or hexagrams, that we see in the Book of Changes today. His son, the Duke of Chou, formulated many of the meanings of the sixty-four images. Subsequently, Confucius and some of his later disciples added their commentaries, ending with what is now called the “Ten Wings” of the I Ching.

It would be impossible to fully delve into Eight Diagram theory here. Suffice to say that these eight images all relate to the Eight Brocades in that the images pertain to the exercises, as well as to qi cavities and meridians, as shown in Part 3.

The Eight Diagrams predate the creation of the Eight Brocades. However, no one is sure whether or not the exercises were originally called Eight Brocades or Eight Diagrams. The assumption is that Li Ching-yun’s teacher (and maybe his whole lineage succession before and after him) chose to call the exercises “Methods of the Eight Diagram Active Kung.” It may have also been that Li’s teacher was able to study the original silks (brocades) of Ma-wang-tui, and so made the connection between the eight exercises presented on them and the eight diagrams of the I Ching. It also may have been that the exercises were originally associated with the eight diagrams and later put on the silks without reference to the eight diagrams. The point, though, is that they do correlate and Li Ching-yun, interestingly enough, was the first person to reveal the correlation and claim that the Eight Brocades can in fact be equally called the Eight Diagram exercises.2

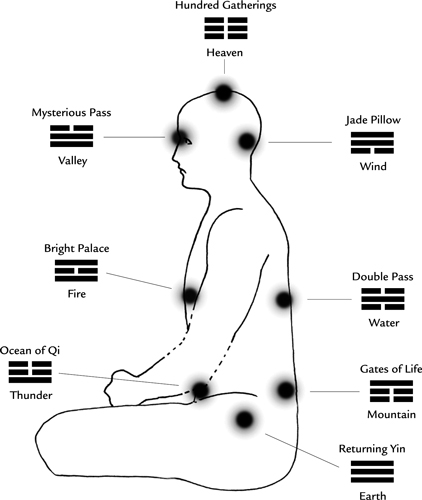

In the Fu Hsi arrangement of these eight images, we find the following correlations to the Eight Brocades practice:

Heaven (Ch’ien), south, the Hundred Gatherings cavity (pai hui, top of the head), corresponds to the First Brocade, the Heavenly Drum.

Thunder (chen), northeast, the Ocean of Qi cavity (qi hai, lower abdomen), corresponds to the Second Brocade, Shake the Heavenly Pillar.

Valley (tui), southeast, the Mysterious Pass cavity (hsuan kuan, between the eyes), corresponds to the Third Brocade, the Red Dragon Stirs the Sea.

Water (k’an), west, the Double Pass cavity (shuang kuan, middle of the back), corresponds to the Fourth Brocade, Rub the Court of the Kidneys.

Fire (li), east, the Bright Palace cavity (chiang kung, solar plexus), corresponds to the Fifth Brocade, the Single Pass Windlass.

Wind (sun), southwest, the Jade Pillow cavity (yu chen, back of the head), corresponds to the Sixth Brocade, the Double Pass Windlass.

Mountain (ken), northwest, the Gates of Life cavity (ching men, kidney region), corresponds to the Seventh Brocade, Supporting Heaven.

Earth (K’un), north, the Returning Yin cavity (hui yin, perineum region), corresponds to the Eighth Brocade, Grasping with Hooks.

The Fu Hsi arrangement of the Eight Diagrams

The fundamental purpose here for the Eight Brocade correlations to the Eight Diagrams rests in the fact that the Chinese have always seen the human body as a microcosmic image of the larger, macrocosmic universe. Human beings are but an archetype of heavenly beings and heavenly structure. The Eight Diagrams are the macrocosmic patterns from which all things (heaven, earth, and man) are created. So as heaven has phenomena that reflect or symbolize each of the eight images, so do earth and man.

The Eight Diagrams are a symbolic representation of the physiological process that restores man’s natural essences of ching, qi, and shen. For when the Eight Diagrams are in their correct positions, heaven’s natural essences (sun, moon, and stars) and earth’s (fire, water, and air) are also in perfect harmony.

These exercises can be performed by anyone as they are very simple. They are regarded as tao yin methods. The secrets of these exercises are versed:

The secrets that follow are included in the original text of the Eight Brocades.

The Eight Diagram relationship to the body

Secrets of the Eight Brocades

Seated cross-legged, close the eyes to darken the heart.

Grasp the hands firmly and meditate on the spirit.

Tap the teeth thirty-six times.

The two hands embrace K’un-lun Shan.

Left and right, beat the Heavenly Drum,

Sounding it twenty-four times.

Gently shake the Heavenly Pillar.

The Red Dragon stirs up the saliva;

Rouse and rinse the saliva thirty-six times.

Evenly fill the mouth with Divine Water;

Each mouthful is divided into three parts and swallowed.

When the dragon moves, the tiger flees.

Stop the breath and rub the hands until hot;

On the back massage the Gates of Life.

Entirely exhaust one breath;

Imagine the heat aflame at the Navel Wheel.

Left and right, turn the Windlass.

Stretch out both feet loosely;

Afterward both hands support the Void.

Repeatedly bend the head over and seize the feet.

Wait for the saliva to be produced;

Rinse and swallow, dividing it into three parts;

Altogether swallow the Divine Water nine times.

Swallow it down with the sound of ku ku;

Then the hundred pulses will be naturally harmonized.

Complete the motion of the River Cart.

Direct the fire to circulate and heat the entire body.

The purpose of these exercises is to prevent harmful influences from approaching, to provide clearness during sleep and in dreams, to prevent cold and heat from entering, and to keep pestilence from encroaching.

These exercises are best practiced between the hours of Tzu and Wu, as doing so will create harmony between Ch’ien and K’un and will establish their proper connection with each other within the cyclic arrangement [of the Eight diagrams]. Hence, everything connected to [the procedures of] restoring one’s original nature and returning to the Tao has excellent reasoning.

Author’s Comments

Close the eyes to darken the heart is a very common phrase in all Taoist works. Close the eyes simply means to shut the eyes so that the mind will not be disturbed by external distractions. To a Taoist, however, closing the eyes can be performed in one of three manners. The first is described as “lowering the bamboo curtains,” which does not mean completely closing the eyes; rather, the eyelids are lowered to the point where just a bit of light still comes through—in the same way that light passes through a bamboo screen. The attention then is placed on the darkened area just above the light, which will prevent sleepiness and distraction. The second type of closing the eyes is to gaze at the tip of the nose, but again with the eyes mostly closed with just a bit of light coming through. The attention of both eyes is placed on the tip of the nose and into the darkness just beyond it. The third way, which also lets in a little light, focuses on rolling the eyes back and slightly upward, without straining the eyeballs. You imagine that you are looking up into the top of the head ( the Hundred Gatherings cavity) or a point between the eyes and back one inch (the shang tan t’ien), looking for a brightness within the darkness.

Darken the heart (ming hsin) refers to the darkness created by lowering the eyelids. When you lower your eyelids, you will experience in your eyes a definite line of light and darkness. It is this darkness on which your attention should be focused. Ming means dark, obscure, or profound; hsin means both heart and mind, the two being synonymous in Chinese thought and language. When translating this term into English, I have usually used the word heart in order to place more emphasis on the idea of will or intent and less on the concept of rational thinking, which the word mind often implies.

Here the term restoring and returning is a reference to cultivating qigong as a means of returning to the Tao, or more simply, a reference to spiritual self-cultivation.

Li includes the following eight-part song in his commentary, but it is not in fact part of the original text.

AN EIGHT-PART SONG IN PRAISE OF THE EIGHT BROCADES

Massaging with warm hands and making use of the saliva produce a beautiful facial appearance.

Author’s Comments

Massaging with warm hands is a reference to dry bathing, which consists of massage exercises that imitate the actions of bathing. Making use of the saliva refers to using the tongue to massage the cheeks and gums.

Pushing up the palms and shaking the head result in the ears not becoming deafened.

Author’s Comments

Pushing up the palms refers to the Seventh Brocade, Supporting Heaven. Shaking the head is another exercise of dry bathing.

Cultivating the two hands to a high level can remove all obstacles.

Author’s Comments

The two hands become the expression of qi when you cultivate to the degree of being able to consciously will qi. In part this means the ability to generate extreme heat in the hands, which can be used for healing.

It is wrong in principle, if, when pounding the body, it causes aching or pain.

Author’s Comments

Pounding the body is a reference to using a pestle, a bag of pebbles, or a wooden pestle to knead the body. (See the Externally Patting the Eight Subtle Meridians and Twelve Cavities regime in Part 3.)

Massaging the soles of the feet until hot will make for lively walking.

Author’s Comments

This exercise is found in the Eighth Brocade, Grasping with Hooks.

Pulling the Windlass means to be free of the work of changing the muscles and tendons.

Author’s Comments

This is a reference to the I chin ching (muscle changing classic), attributed to the Buddhist patriarch Bodhidharma.

Gazing fiercely like a tiger and arching the back regulates the wind.

Author’s Comments

Wind refers to the breath.

With proper breathing, the five viscera can all be void of any harmful afflictions.

Author’s Comments

For the viscera (heart, lungs, kidneys, liver, spleen), there is not only a proper breathing method to strengthen them but a sound, color, and exercise as well.

Within the exercises of the Eight Brocades, and implied above in Li’s eight- part song, you’ll find that eight very distinct types of therapeutic methods are applied. The very heart of these therapies lies in enhancing your ability to sense and feel the inner and outer workings of body and mind. Once you establish a foundation of increased sensitivity to yourself, then the subtle inner energies of ching, qi, and shen can not only be experienced but also be consciously applied.

The first therapy is the method of massage, such as the patting and pressing aspect of the Heavenly Drum, the pressing activity in Shake the Heavenly Pillar, the rubbing of the kidneys and heating of the hands in Rub the Court of the Kidneys, and the massaging of the Bubbling Well (yung ch’uan) cavities in Grasping with Hooks.

The second is the use of sound, as in the tapping of the Heavenly Drum, listening to the breath, hearing the sound of ku ku, and using the five half coughs.

The third is the therapy of visualization, as in imagining a fire burning in the lower abdomen, producing light in the Jade Pillow cavity, or imagining the qi circulating in the body.

The fourth is the method of twisting and stretching, as seen in Shake the Heavenly Pillar, the Single Pass Windlass and Double Pass Windlass, Supporting Heaven, and Grasping with Hooks.

The fifth is the method of breath control, of which four main types are used: cleansing breath (ching hsi), natural breathing (tzu hsi), tortoise breathing (kuei hsi), and stopping the breath (pi qi).

Cleansing breath involves breathing in through the nose and exhaling through the mouth while making an aspirated ha or ho sound. This type of breathing aids in ridding the body of any impurities in the nose, lungs, and throat. It is usually performed nine times with any type of qigong exercise.

Ha is one of the Six Healing Sounds, part of a practice common to almost all Taoist traditions. The sounds are ha, hu, shi, hisss, shu, and fu. Each sound should be produced during exhalation with a noticeable aspiration. Made from the lower abdomen as it contracts and pushes the air upward, the sounds vibrate and pass through the throat—but do not come from there. Ha is used to heal the heart. While sitting, place the hands, with fingers intertwined, behind the head and utter ha thirty-six times. Hu cures the spleen. While sitting, place the hands over the tan-t’ien area (the lower abdomen) and pronounce the hu sound thirty-six times. Shi cures the solar plexus. While sitting, place the hands over the kidney area and sound shi thirty-six times. Hisss cures the lungs. While standing, intertwine the fingers behind the head and utter hisss thirty-six times. Shu cures the liver. While sitting, place the hands, fingers intertwined, behind the head and utter shu thirty-six times. If the abdomen is overly warm, lie down on the back with eyes closed and sound shu thirty-six times. Fu cures the kidneys. Sit on the floor, place the arms around the knees with the fingers intertwined, and pronounce the sound fu thirty-six times.

Natural breath is breathing through the nose only. During the inhalation, as the abdomen naturally expands, attention is focused on feeling the expansion of breath at the lower spine as well. On the exhalation, as the abdomen contracts, attention is paid to the contraction of the front of the lower abdomen. Natural breathing occurs though intent. Focusing on these areas will help you work your entire abdomen and allow you to push up air naturally through the diaphragm and into the lung area. Gradually, you will be able to feel the inhalation rise up from the lower spine to the middle of the back, and then feel it sink, on the exhalation, from the solar plexus down into the lower abdomen. This cannot be made to happen physically, or externally, by forcing the expansion or contraction with the muscles. You must allow it to happen naturally, and internally, by paying attention and applying your mental intention.

The use of mental intention in connection with the breath plays a very important role in holding the breath and in tortoise breathing. In holding the breath, it is the mental intention that leads the breath through the Function and Control meridians (the Lesser Heavenly Circuit) to locations of injury or pain. In tortoise breathing, mental intention leads the swallowed breath (as well as the swallowed saliva) down into the lower abdomen. The whole notion of using mental intention—at first through your imagination—is of utmost importance.

Holding the breath, or embryonic breathing, takes on several forms in the Eight Brocades practice. For one, you hold the breath while counting heartbeats, usually twelve (in advanced practice, the number would be sixty, one hundred twenty, or one thousand). For another, you hold the breath for two heartbeats after completing the inhalation and then count your heartbeats (twelve or more) while performing the exhalation referred to in the texts as “exhausting one breath completely.” You also hold the breath when heating the hands for massage. And finally you hold the breath in order to either lead qi to a specific area or circulate it through the meridians.

In order to guide the qi when holding the breath, you should practice applying the Four Activities: (1) draw in the anus; (2) place the tongue on the roof of the mouth, thus forming what is called the “magpie bridge”; (3) close the eyelids and roll the eyes upward and back to visualize the Hundred Gatherings or Jade Pillow cavities—don’t strain the eyes, just look back as far as you comfortably can; and (4) inhale slowly and after a complete inhalation, hold the breath for twelve or more heartbeats. As you hold your breath, imagine the qi moving up from the Returning Yin cavity to the Hundred Gatherings cavity. (The locations of these cavities and how to practice acquiring qi in them are explained in Part 3.)

Tortoise breathing is the process of what is sometimes called ingesting qi or saliva. This is applied in the Red Dragon Stirs the Sea brocade and in the Lesser Heavenly Circuit regime described in Part 3. Tortoise breathing should be combined with the Four Activities. With the fists raised above the head (see the instructions for the Third Brocade), and after holding the breath and imagining the qi moving up to the Hundred Gatherings cavity, swallow the air or saliva, and exhale, sensing the the qi or saliva dropping down into the lower abdomen (tan t’ien).

The reader should note that reverse breathing is not applied in the Eight Brocades, nor is it used in most Taoist practices (or “soft” styles of martial arts). Found predominately in the kung fu or “hard” styles of martial arts, reverse breathing is the opposite of natural breathing. In reverse breathing, the abdomen is contracted on inhalation and expanded on exhalation. Reverse breathing accentuates the external expression or aspects of qi but does little in the way of actual internal accumulation of qi. And, unless you have accumulated sufficient qi, reverse breathing has little function and can cause negative side effects internally. Because the inhalation works in conjunction with contracting the abdomen, the breath is sent high into the upper back and shoulders, and into the head—which can cause many problems. Do not perform reverse breathing with these exercises. All of my teachers have unanimously advised not to bother with reverse breathing. Master Liang referred to it as “big-head breathing” because more often than not that is the end result.

The sixth therapy is that of swallowing, which begins with the saliva and later includes the breath itself.

The seventh therapy is the use of meditative techniques.

And the eighth therapy is the circulation of qi through the Function and Control meridians (the Lesser Heavenly Circuit).

The therapies and exercises of the Eight Brocades can lead you far along the path of learning how to take care of yourself. If you can discipline yourself and practice each day, you will notice over time an incredible difference in your vitality and sense of well-being. Later on, as you continue to improve your concentration and become more adept at the exercises, the rewards will be even greater, both physically and spiritually.

In the verses above, we can observe the methods of the Eight Diagram Active Kung [Eight Brocades], which really are the very best and most wondrous methods for invigorating the body. Yet, most people, because of their life situations, even if they obtain these verses and songs, are unable to understand their profound meaning. Because of this, they live in contradiction of what is natural. It would be wise for them to begin by putting forth every effort into these exercises, so that they will no longer suffer and toil their lives away. Some will want to practice only during their leisure time, but this type of training is insufficient. Alas! How unfortunate the result, as these types of persons only bring about their early and hurried death.

Author’s Comments

Li Ching-yun always referred to the Eight Brocades as the “Eight Diagram Active Kung,” so I have chosen to preserve that terminology when translating his voice.

Formerly, when my master first considered me able enough to teach these exercises, I found their principles to be beyond my comprehension: so subtle and abstruse, limitless and yet of one nature, but different in form. However, I did understand that they could aid society and benefit the minds of all people. After a time, I found the desire to teach.

Once, I asked my teacher why he had not previously dared to transmit these teachings to others, especially to other Taoist sects. His response was:

Because those in the various sects obtain teachings and then change them according to their liking and to suit the tenets of their sect. They in turn go on to transmit them to others; then these persons change them again to their liking and proceed to transmit them—too much of the original teaching is then discarded and lost. Therefore, I am giving you the responsibility of imparting these teachings correctly. You must transmit them as broadly as possible, for if only one person were able to practice these exercises, then only one person would attain a good old age. If only one thousand and eight persons practice these exercises, then only that many persons would acquire health in old age. However, by widely transmitting this profound Tao of living beyond one hundred years, all the people of China would be able to attain a good old age, and all the people of the ancient state of the great Han could also have attained a good old age as a nation.

Author’s Comments

Perhaps an explanatory note is necessary here to bring Li’s meaning into focus. What he is saying is that if all the Hans (which was Li’s race) had begun practicing the Eight Brocades when he did, during the time when the Hans ruled China, rather than the Manchus, they would all still be alive, and by extension, so would the great ancient state of the Han people.

Therefore, the following commentary on the original text of the Eight Brocades is given so that these teachings can be widely transmitted to the various Taoist sects. For herein lie the secrets, explained line by line, that reveal the subtle knowledge contained in these exercises. This commentary will, it is hoped, aid everyone in practicing the Eight Diagram Active Kung [Eight Brocades] in the proper sequence, and impart a correct understanding of the procedures so that all may realize their completion.