Christianity’s Sophisticated Solution

During the night of July 31, 1976, a sudden storm dumped fourteen inches of precipitation in just a few short hours high up in the Colorado mountains. The accumulated rain had nowhere to go but down, and down the canyon of the Big Thompson River it went. This scenic, winding river became a torrent with a twenty-foot wall of water cascading through the valley at seventy miles per hour, taking with it exploding propane tanks, bridges, cars, branches, boulders, and people—people whose clothes were ripped off their bodies by the speed and severity of the flood. Nearly 150 of those camping and fishing in the canyon that night were drowned.

Among those in the valley was a group of thirty-five women leaders from Campus Crusade for Christ, including Vonette Bright, the wife of Bill Bright and cofounder of the international movement. These unsuspecting women were singing and praying when they heard the shrill state-trooper-megaphone calls to evacuate immediately. They piled into several cars and tried to flee the ranch. Some of the cars made it to higher ground by following the police, and the occupants were forced to scramble up onto the mountain to spend the dark night waiting. But in the blackness, two of the vehicles got separated and were swept off the bridge. A couple of the women in those cars made it out of the windows and tumbled down the river, mouths and noses and lungs stuffed with mud, debris, and rocks until miraculously both of them hit trees that they were able to climb and wait out the storm and the night. The others were lost—seven of the thirty-five women.

One of those who survived that traumatic night was Ney Bailey (along with Vonette Bright). As she struggled to process what had happened, she was overwhelmed with grief, fear, questions, and, undoubtedly, what today we would call survivor guilt. Her years of faith had also trained her in the habit of giving thanks. And in brokenhearted authenticity, along with thousands of other Crusade staff from all over the world, she offered praise and thanksgiving to her God, expressing trust in God’s goodness and trustworthiness in all things.

And she wrote a book. To help her in her struggle against becoming bitter and cynical, Bailey honestly explored her range of emotions and put them down in writing to help others. That book, Faith Is Not a Feeling, is still in print more than forty years later.

Just over ten years after the Big Thompson River flood, I met Jesus through the witness of a Crusade staffer, who was part of the ongoing legacy of the faithfulness of the Campus Crusade organization. And shortly after that, as a passionate young man, brand new to the Christian faith and full of baggage and disordered emotions, I was given Faith Is Not a Feeling to read. And it helped. Ney Bailey’s wisdom was not to ignore emotions, as the title might imply and which has been the source of some criticism. Rather, she emphasized that faith in God is more than our feelings—emotions that will inevitably range through positive, negative, and numb. Additionally, faith in God can bring us through debilitating and destructive emotions like bitterness into a place of joy and gratitude and peace.

We have been discussing the central role that emotions have played and continue to play in a philosophy of life. What about the Bible and Christianity? If it is true, as I am arguing, that Christianity is offering a philosophy of life, that Christianity is thoughtfully addressing the great human questions and experiences, then it must be that Scripture has something important to say about emotions. If the Bible and Christianity ignored emotions altogether or presented a simplistic or patently wrong view of emotions, then it would not be worthy of the label of “whole-life philosophy.” Have no fear (or any other negative emotion). When we turn to the Bible and ask whether it speaks to the question of emotions, we find that the answer is more than a generic yes. Emotions prove to be a large, nuanced, and practical area of discussion all throughout Scripture, as they are rightly part of what it means to live a Good Life. The Bible and Christianity have a remarkably sophisticated philosophy of emotions.

To understand something complex and nuanced, it is often helpful to consider it in contrast to what is surrounding it. In sculpture, this is called relief (from the Latin verb relevo, “to raise”). Relief sculpture stands out from the surface it is carved out of and connected to, as opposed to a freestanding sculpture on a plinth.

Christianity’s ornate and sophisticated philosophy of emotions stands in relief to its surroundings, both in the ancient world and today. To understand the Bible’s approach to emotions, we will consider ways in which it is similar to and distinct from the philosophies of emotion on offer in the world.

Figure 7. Angel sculpture on a plinth, Pont Sant’Angelo, Rome [Shutterschock / Shutterstock.com]

First, the similarities. Christianity is a religion, meaning it deals with the divine and makes deep claims about the nature of reality, but it is also more than that. As a religion, Christianity provides liturgies—customs and habits that shape the sensibilities of its believers and direct them to worship a Being outside of themselves. But recall that for the philosophers, especially at the high point of the Hellenistic period, this is precisely where the discussion of emotions is so important. Reasoned philosophy, not just religion, was crucial to living a good and peaceful life (eudaimonia and ataraxia). That is, unlike what the religions of the day had to offer, with their uncontrolled ecstatic emotional exuberance, the philosophers proposed a wisdom-loving way of thinking and living that could educate the emotions. The key to life was found in philosophy—a practiced learning to see and be in the world in certain ways.

Figure 8. Relief from the Arch of Titus, depicting the capture of the menorah from the Jerusalem temple [graceenee / Shutterstock.com]

So at first this would seem to mark a difference between Christianity and its contemporary philosophies. However, the key is to recognize that Christianity is not merely a religion, but is a religious philosophy. Like the philosophical traditions with which it is dialoguing (in relief), Christianity does not encourage ecstatic emotional practices like its contemporary religions. Rather, it considers the emotions as important but controllable by proper reasoning. Thus, within its religious metaphysic, Christianity presents itself as a philosophy that is aware of the importance of educating emotions.

Even with the church practices of speaking in other tongues and prophesying—what to outsiders would be classic dangerous religious exuberance—the New Testament is remarkably restrained. The apostle Paul addresses this directly, giving strong instructions about how to handle these Spirit-inspired utterances. Church services must be conducted with order and wisdom (1 Cor. 14:26–40). If not, outsiders will wrongly perceive that Christians have lost their minds (14:23). That is, without controlling emotional outbursts, people will wrongly suppose that Christianity is just another example of foolish religion. Instead, Christianity is an astute religious philosophy that exercises thoughtful restraint.

This leads to another crucial similarity between Christianity and its contemporary philosophies: Christianity’s cognitive approach to emotions. Like the Aristotelian tradition and unlike the Platonic one, the Bible’s view of emotions is not that they are irrational and bad, uncontrollable and dangerous. No, emotions are inextricably woven with our ethics, habits, understanding, and bodies—in short, what it means to be human. Emotions are part of life and are not to be avoided, but they must be educated through a thoughtful way of seeing the world.

Christianity is also similar to its surrounding philosophies in anthropological understanding; specifically, where emotions reside in us as humans—in the heart. Every language uses body parts as metaphors for something deeper. Various languages metaphorically place emotions in different parts of the body. In Greek, for example, compassion is found in the intestines. For Turks, love is in the liver.

The Bible regularly uses the metaphor of “heart,” but not in the way that modern English does. In English, the heart metaphor is used primarily as a container for emotions, especially love. Our word “heart” today connotes emotions as opposed to reason. So “heart” can be laid side by side in contrast with “head”—emotions versus reason. This contributes to the conflation of “passions” and “affections” in how we use our word “emotions.”

But the situation is very different for the Bible. In both Hebrew and Greek, the words that are translated into English as “heart” are broader and shaped differently. The Hebrew leb and the Greek kardia mean the inner person in comparison with the outer; the true person as a thinking and feeling being is what “heart” indicates. In this, Christianity’s understanding of emotions overlaps significantly with its surrounding cultures—Jewish, Greek, and Roman. The true inner person includes both reason and emotion. We cannot fully separate head and heart.

So we are beginning to see that, when examined in the cultural and intellectual context of its day, Christianity makes sense as a philosophy, addressing the central role that emotions play in a whole philosophy of life. But here is where the beautiful and striking relief sculpture that is Christianity stands out. There are substantial differences in the Bible’s philosophy of emotions that reflect a distinct metaphysic.

What are the distinct aspects of the Christian philosophy of emotions?

First, the God of the Bible has emotions and he is thoroughly good. In Greek and Roman mythology, which had a lasting cultural impact even in the philosophical era, the gods were often seen as the source of fickle and bad emotions. On the contrary, the biblical understanding, in both the Old and New Testaments, was that the true God also experiences emotions, but not in an uncontrolled way, and never capriciously; God is not ornery, tempting and messing with humans and their emotions. But neither is God emotionless.

In the Bible God is described as having emotions such as anger, jealousy, grief, joy, satisfaction, and, most of all, love.1 Very often God is described as having and acting from real emotions. Out of a proper concern to not think of God’s emotions in purely human terms, theologians have often emphasized God’s “impassibility.” You can see the word “passions” hidden in there, negated. The doctrine of impassibility means that God is not fickle and untrustworthy, because he does not change and shift. It means that it is impossible for God to succumb to passions out of his control. That’s true and good (Num. 23:19; Mal. 3:6; James 1:17). But unfortunately, for many people in the modern period impassibility has come to mean that God is emotionless.2

Impassibility, however, should not be understood to mean God lacks emotions and that the many references to God’s emotions should be written off as mere human projections onto him. This common approach to God’s emotions reflects a Platonic and/or Stoic view of emotions as inherently bad and untrustworthy, a view that the Bible does not share. If one believes all emotions are bad, then obviously God cannot have them. But the problem is in that assumption. Emotions are part of reasoning and being human, and the fact that humans have them as part of our being made in the image of God (not just as part of our sinfulness) speaks positively to God’s emotions.

The problem with human emotions is with the human part, not the emotions part. Humans, who are both limited and broken, have emotions that can necessarily be ill-formed, perverted, and disordered. God, who is incorruptible and perfectly whole, has emotions appropriately and perfectly. As one writer helpfully says, “Because God has an infinite mind, infinite power, and an infinite heart, emotions don’t disrupt God’s character. They don’t move God to act in ways that are anything other than ultimately loving.”3

If anyone is still hesitant to think of God as having emotions, we need only consider the clear testimony of the Gospels, which repeatedly show the incarnate Son of God, Jesus, as a fully emotional being. To be human is to have emotions, and that is a good thing, with Jesus as the ultimate model. John Calvin notes that “those who imagine that the son of God was exempt from human passions, do not truly and seriously acknowledge him to be a man.”4 But we need to go further and be clear that the emotions of Jesus are not only part of his being human but also reflections of the Triune God’s own proper and full experience of emotions.

B. B. Warfield astutely observes that many Christians have tended to ignore or disregard Jesus’s emotions because of the latent influence of the Stoics. Recall that the Stoics emphasized that the ideal state was one of apatheia, freedom from all emotions and a kind of detachment from the world.5 This notion of perfection as freedom from emotion has lingered and haunted the Western mind ever since, causing us to miss the central role that emotions play in Jesus’s own life and teaching.

Jesus wept (John 11:35). The significance of this two-word verse is not only that it is handy for kids who are required to memorize a Bible verse. More importantly, it is a glimpse into the emotional world of Jesus. Jesus wept, marveled, hoped, longed for certain things to happen, and lamented (Matt 8:10; 27:46; Luke 19:41; Heb. 12:2).

When we read the four Gospels with our receiver tuned in to the emotions frequency, we will see that of the many emotions ascribed to Jesus, there are three that occur most frequently. Jesus is first of all described as compassionate, as feeling loving pity and care for people. This motivates his countless days and nights of healing people and his ultimate work of giving his own life (Matt. 9:36; 14:14; Mark 1:41). Second most often, Jesus is shown to be angry—at compassionless people primarily, but also at injustice and consequences of the fall, like death (Mark 3:5; 11:15–19; John 11:38). Third, Jesus is shown to be joyful. He rejoices regularly, gives thanks joyfully in all circumstances, and instructs his disciples to do the same (Luke 10:21; John 15:11; 17:13).

Figure 9. Dome mosaic from Sant’Apollinare in Classe [IZZARD / Shutterstock.com]

A joyful Jesus is maybe the most unexpected picture we get of Jesus in the Gospels—unexpected because so much of sacred art throughout the centuries has pictured Jesus as dour and always serious. This is especially so in the Western tradition, which focused its theology and images on Jesus’s suffering. Crucifixes become primary, and Western church architecture reinforces this with cathedrals built in the shape of a cross (as compared to the octagonal basilica of the Eastern tradition, which primarily depicts Jesus as risen and blessing others). I remember being struck by this difference when visiting the various churches in Ravenna, Italy, some of which are ancient Eastern-style basilicas and others baroque-era Western-style churches.

Figure 10. Altar with crucifix in the Cathedral of Ravenna [GoneWithTheWind / Shutterstock.com]

In a class I teach on the Sermon on the Mount, I often show various film versions of Jesus’s famous mountainside homily. There is one that unsettles many students. It’s not the black-and-white, jarring offering from the Italian Marxist Pasolini. It’s not the brilliant Claymation version. It’s the film where Jesus is happy. In the Visual Bible version, Jesus delivers the Sermon on the Mount in a dialogical, loving, and engaging way, even laughing along with the crowd at some of the absurd images he uses, like the would-be plank-eyed surgeon (Matt. 7:3–5). This shocks us. We want our Jesuses to have nice British accents and not be very emotional, and especially not cheerful! So students are often taken aback at this happy Jesus.

But it is worth noting that in contrast with John the Baptist, Jesus was described as eating and drinking, and indeed was maligned as a glutton and wine-imbiber, a friend of publicans and sinners. He went to a lot of dinner parties. There is nothing to indicate he was habitually sorrowful, dour, and overly serious. After all, people—regular, nonreligious people—were very attracted to him. He must have been accessible, warm, and joyful.

Jesus was a real person and so experienced the many emotions that accompany our physical experiences, including negative ones—thirst, hunger, weariness, pleasure. Jesus wailed, raged, was agitated, and was openly joyful. His last moments included a wholehearted cry of despair (Matt. 27:46). As Warfield observes, “Nothing is lacking to make the impression strong that we have before us in Jesus a human being like ourselves.”6

And at the same time we see in Jesus’s humanity a picture of the complete human who reflects God’s own image in a way that no sinful human has (Heb. 1:1–4). Jesus was fully emotional, but in a way that was always harmonious, not imbalanced, inappropriate, or disordered. Both compassion and indignation are joined together and exercised rightly. “Joy and sorrow meet in his heart and kiss each other.”7 Jesus’s emotions are full and strong, not pale, but they never master him or function wrongly. In this the begotten Jesus images the Triune God’s emotional life and also provides an imitative model for us, who are made in God’s image but are broken and disordered. Emotions are good and necessary when educated.

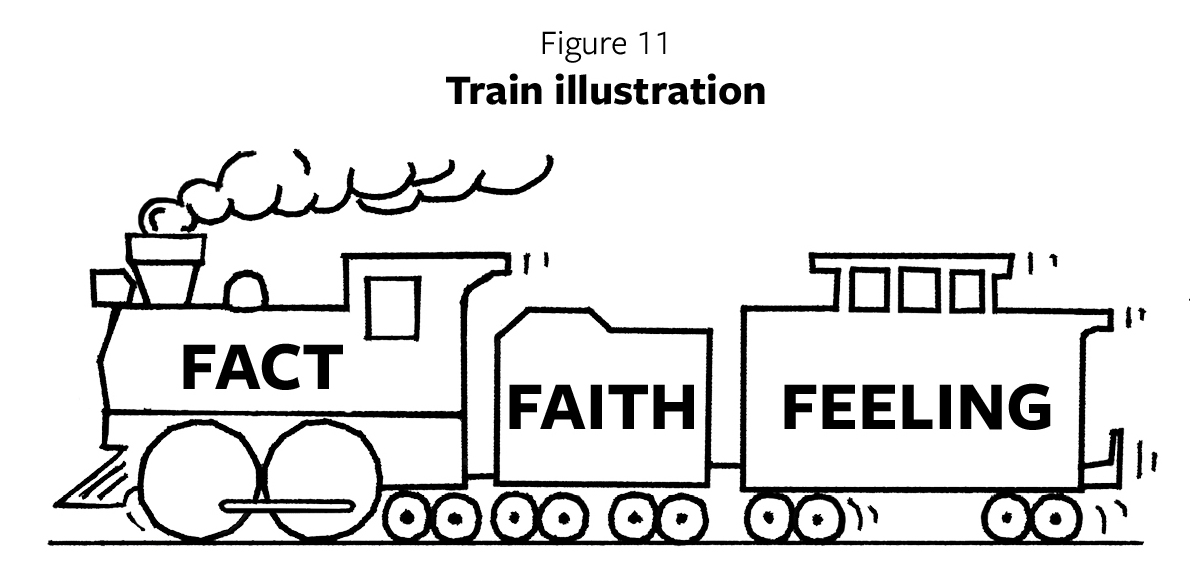

In addition to Ney Bailey’s Faith Is Not a Feeling, another influential Campus Crusade teaching in my university days was the train illustration. Figure 11 depicts the Schoolhouse Rock!–era version of it that I was familiar with.

The point of this little image is this: Faith in the historical facts of God’s love for us in Jesus is what drives our lives, while feelings may or may not follow along; emotions are not central to our Christian lives and certainly shouldn’t be given the leading role.

[Inspired by a Cru illustration]

This teaching from Crusade’s little booklet on how to live “the Spirit-filled life”8 can be interpreted positively or negatively. Positively, along with Bailey’s Faith Is Not a Feeling, this Fact-Faith-Feeling model is beneficial in recognizing that we can’t base our lives merely on the fickleness of emotions. Especially as a central teaching for university-attending eighteen-to-twenty-two-year-olds at such a crucial and emotionally tumultuous time (with not-yet-fully-developed frontal lobes and lots of sudden freedoms), this is to be commended as wise guidance. I know I needed it. Additionally, even though this is probably not what the designers were thinking, one could interpret this illustration in line with a cognitive approach to emotions—that emotions are primarily the result of, or subsequent to, cognitive judgments.

But on the negative side, this train illustration could be interpreted and applied as another unhelpful promoter of the negative-view-of-emotions tradition. By relegating emotions to a noncrucial role, as something that may or may not be there in our lives, as unrelated and nonessential compared to the “faith in the facts” engine, we may unwittingly fall back into this Platonic view of emotions. Many Christians have been taught to view emotions this way. This is a problem because this is patently not the view of the Bible and Christianity, as we have begun to see and will discuss more momentarily.

Even if we don’t adopt a fully antiemotion view from the train illustration, many people, like I did, take away the sense that emotions are suspect and to be kept somewhat at bay, a kind of unarticulated Christianized Stoicism.

There is another important way that Christianity’s sophisticated view of emotions stands in relief to the surrounding philosophies of the day: the question of detachment.

We noted that around the same time as Jesus, Stoic philosophy was very widespread and influential—and understandably so. Stoicism was a very thoughtful whole-life philosophy that offered practical advice on how to live uprightly and find happiness. It had influential and virtuous advocates like Seneca and the later Roman emperor Marcus Aurelius.

Stoicism’s answer to the great human question of happiness, which has remarkable similarities to its contemporary Buddhism farther east, is that one must learn to be detached from all circumstances and the emotions they evoke, both good and bad. Only this kind of studied detachment will enable one to find ataraxia and eudaimonia (tranquility and happiness).

In comparison to this very practical and often effective practice, the Christian philosophy of emotions shows remarkable refinement. Unlike with Stoicism, emotions are not to be disregarded, ignored, minimized, vilified, or placed in the “unimportant and untrustworthy” category. Quite the contrary. As we have already seen, God is described as having emotions, and Jesus models a full emotional life. Additionally, a full range of emotions is displayed by God’s people throughout the whole Bible, and they are not condemned or written off as merely “emotional” for expressing their very human feelings. Indeed, the heart and center of the Old Testament is a book of songs (Psalms) that articulates and commends the emotional life. King David, the author of many such psalms, is one of the trifecta of most important people in the Old Testament (along with Abraham and Moses), and he was known for his deep passions and display of emotions (2 Sam. 6:5–16; 19:1–4).

Moreover, throughout the Old and New Testaments many emotions are explicitly commanded and commended:

- Rejoicing (Rom. 12:15; Phil. 3:1; 4:4)

- Having compassion (Zech. 7:9–10; Eph. 4:32; Col. 3:12; 1 Pet. 3:8)

- Being patient (Rom. 12:12; Eph. 4:2; 1 Cor. 13:4)

- Grieving and regretting (Joel 2:13; Acts 2:38; 2 Cor. 7:10)

- Fearing and not fearing (Isa. 41:10; Matt. 10:28)

- Loving (John 13:34–35; 15:12; Rom. 13:8; Col. 3:14; 1 Pet. 4:8; 1 John 4:7–10)

So to put it most simply: the Bible’s view of emotions is cognitive but not Stoic; emotions are controllable, but detachment from emotions is not valued or good.

Yet here is where the nuance of the Christian philosophy comes into its fullness. While promoting the good of emotions, Christianity also recommends a measured and intentional detachment from the world and its circumstances for the sake of living a tranquil life. The apostle Paul, who experienced the heights of joy and passion (Phil. 1:18; Col. 1:24), also knew firsthand the depths of despair, pain, and grief (Rom. 9:2–4), even describing his emotional experience at one point as living with the feeling of a sentence of death hanging over everything he did (2 Cor. 1:8–9).

Yet, like a good philosopher, Paul also says that he has learned how to be content regardless of his circumstances and feelings. Writing to the Christians living in the Roman colony of Philippi, Paul gives several specific instructions regarding emotions. “Rejoice in the Lord always. I will say it again: Rejoice!” (Phil. 4:4); “Do not be anxious about anything, but in every situation, by prayer and petition, with thanksgiving, present your requests to God” (4:6).9 The result of these cognitive-emotive choices will be the kind of peace that every soul longs for—a transcendent peace that comes from God himself (4:7). Emotions are part of what it means to be Christian.

But then Paul drops a line the great Stoic Seneca would be proud of: “I have learned to be content whatever the circumstances. I know what it is to be in need, and I know what it is to have plenty. I have learned the secret of being content in any and every situation, whether well fed or hungry, whether living in plenty or in want” (4:11–12).

So emotions matter, yet Christians must have a measured detachment from circumstances that would normally cause the range of emotions. That’s a very nuanced position. How can one pull this off? The Stoic answer seems easier—just concentrate on detachment, because life is too unpredictable.

But Christianity is very clear on how one can walk this fine line of full emotions with measured detachment. The answer to this great human question is profoundly divine. And as always, the Christian understanding is rooted in the person of Christ. We don’t have to wonder what the secret is. Paul tells us: “I can do all this through him [the risen Jesus] who gives me strength” (Phil. 4:13).

Paul got this transformative understanding from Jesus himself, both his teaching and his example. Jesus, not insensitive to the emotions of his disciples, instructs them to rejoice (an emotion) in the midst of persecution, suffering, and rejection (all emotions and emotion-evoking). How? Through the knowledge that such unjust suffering and emotional distress has been endured by God’s faithful prophets in the past and through the sure hope that God will reward, restore, and recompense all those who have suffered on his behalf (Matt. 5:10–12). This is neither mindless emotional exuberance nor studied emotional detachment. It is a fully emotional life educated by knowledge and hope in God.

Jesus also models this himself in his darkest hour. With distress sufficient to produce drops of blood, even while his close friend was betraying him, knowing the anguished pain and shameful experiences he was about to endure, Jesus prayed (Matt. 26:36–46). His garden of Gethsemane prayer becomes the model of real emotions educated through faith and hope in God. “Not my will but your will be done” is the posture that manifests Jesus’s practiced and wholehearted philosophy of emotions. He is fully present to his emotions, even painful ones, and yet finds peace through turning in trust to the divine Father.

One of the strengths of Aristotle’s cognitive view of emotions is that it accounts for the reality that emotions are integral to morality and ethics. The moral agent’s emotions are both revealing of a person’s character and a necessary part of what it means to be moral. Contrary to the view of ethics that has dominated in the modern period, morality is more than a set of right-and-wrong principles. The moral agent’s virtue (including emotions) is a necessary part of ethics.

Unfortunately, Christian ethics in the modern period has often suffered from the Kantian missteps, especially in the Protestant tradition. Many Protestant ethicists have perpetuated a view of morality that is correct in emphasizing that morality is based on God’s revelation but have missed the central role that the virtue of the moral agent plays. Failing to appreciate the Bible’s nuanced philosophy of emotions has been one of the consequences of this ethical understanding, while at the same time it has also contributed to this insufficient ethical approach.

Central to Hebrew life is the Shema: “Hear, O Israel: The LORD our God, the LORD is one. Love the LORD your God with all your heart and with all your soul and with all your strength” (Deut. 6:4–5).

When Jesus is asked about what the greatest commandment in the Bible is, he answers with the Shema plus a crucial addendum:

“Teacher, which is the greatest commandment in the Law?”

Jesus replied: “‘Love the Lord your God with all your heart and with all your soul and with all your mind.’ This is the first and greatest commandment. And the second is like it: ‘Love your neighbor as yourself.’ All the Law and the Prophets hang on these two commandments.” (Matt. 22:36–40)

Notice that this central biblical teaching is a command to have a certain emotion—specifically, love. Love is more than an emotion, but it is not less than one. Love is a way of seeing and being in the world that is rooted in the heart, which necessarily includes the emotions. God’s people are regularly commanded to obey—to do certain actions and to avoid others. But undergirding all of these commands and arching over them all are the two greatest commandments, which focus on love. To do what is moral, to be ethical, requires obeying God with love, and this obedience focuses on the emotions of the person.

Throughout the Gospels Jesus has sharp and repeated conflict with one group more than any other—the morally and religiously conservative “scribes and Pharisees.” What is the source of Jesus’s tension with this group? It is not their conservative view of the authority of Scripture or that their moral practices are all wrong. Jesus promotes many of the same views as the Pharisees regarding the sanctity of marriage and good practices such as fasting, prayer, giving to help the poor, and meditating on Scripture.

Jesus’s pointed critique of the scribes and Pharisees is focused not primarily on their behavior but instead on an emotional failure, a moral breakdown at the level of their emotions. He calls them “hypocrites” not because they are living secretly immoral lives but because there is a disconnect between their otherwise good outward actions and their inner person, their hearts.

What is the scribes’ and Pharisees’ problem? It is cardial. It is emotional. When they see the needs and suffering of others, they lack compassion; they value strict adherence to external laws over love for those in need (Matt. 12:1–14; 15:1–9). When they pray, fast, and give money to help the poor, their motives (which are rooted in emotions) are disordered and misplaced; they love the praise of other humans over that of God (Matt. 6:1–21). When the Pharisees are full of anger, lust, or a desire for vengeance, it is the opposite of being righteous, even if no immoral outward actions are performed. To not murder is good, but real righteousness requires one not to be angry and hateful. To avoid adultery is good, but real righteousness requires one not to be driven by lust (Matt. 5:17–48). Anger and lust are emotions, not just actions. Righteousness includes emotions.

That’s the negative side of things. Christianity critiques any type of morality that ignores or dismisses the central role of emotions. But Christianity also speaks positively about the importance of emotions. In many New Testament texts, Christians are described in particular ways for the purpose of exhorting them toward certain practices and habits. Over and over again these descriptions direct our energies toward educating our emotions.

For example, take Paul’s description of two possible human states—the Christian filled with God’s Spirit versus the person left in a merely human state, “in the flesh.” After quoting Jesus’s command to “love your neighbor as yourself” (Gal. 5:14), Paul speaks about these two opposing realities in terms of their desires—the Spirit and the flesh have passions/emotions/desires that are contrary to each other (5:16–17). The subsequent description of those in the flesh includes a list of immoral practices, but not only practices—it also includes specific fleshly emotions (bolded): “The acts of the flesh are obvious: sexual immorality, impurity and debauchery; idolatry and witchcraft; hatred, discord, jealousy, fits of rage, selfish ambition, dissensions, factions and envy; drunkenness, orgies, and the like” (5:19–20).

By way of contrast, the Spirit-filled person manifests an opposite set of emotional habits—both direct emotions and habits motivated by certain emotions, capped off with the summative description of self-control over emotions: “But the fruit of the Spirit is love, joy, peace, forbearance, kindness, goodness, faithfulness, gentleness and self-control. Against such things there is no law” (Gal. 5:22–23).

Paul’s final description of the Spirit-filled Christian is appropriately summed up with a spiritual application of Jesus’s own physical crucifixion, showing that the Christian is defined as the person who by the Spirit and union with Christ has gained control over these negative “fleshly” emotions: “Those who belong to Christ Jesus have crucified the flesh with its passions and desires” (Gal. 5:24).

So to be filled with the Spirit is to have certain emotions and to learn to control other ones.

The Christian community is also often described in ways that reflect Christianity’s philosophical commitment to educating our emotions. The fruit of the Spirit that we have just discussed are manifested in relationship to others. Other texts explicitly focus on the corporate life of Christians, and these are once again full of exhortations to avoid certain emotions and cultivate others.

Romans 12 is a good example. While discussing the different Spirit-gifts that God has given people for the building up of the church, Paul encourages people to use these gifts in certain emotion-sensitive ways—giving with a generous heart, leading with diligent care, and showing mercy toward others cheerfully (Rom. 12:8).

This leads Paul to his favorite topic, following Jesus’s own lead—love. Notice once again how many particularly emotional traits are identified in this high-level description of church life (emotions are bolded; actions motivated by a certain emotion are italicized):

Love must be sincere. Hate what is evil; cling to what is good. Be devoted to one another in love. Honor one another above yourselves. Never be lacking in zeal, but keep your spiritual fervor, serving the Lord. Be joyful in hope, patient in affliction, faithful in prayer. Share with the Lord’s people who are in need. Practice hospitality.

Bless those who persecute you; bless and do not curse. Rejoice with those who rejoice; mourn with those who mourn. Live in harmony with one another. Do not be proud, but be willing to associate with people of low position. Do not be conceited. (Rom. 12:9–16)

We should not overlook a final set of corporate emotions that Christians are exhorted to cultivate—rejoicing, singing, and giving thanks. Repeatedly Christians are told to rejoice, to be thankful and to express this, and to engage in singing (Pss. 9:11; 149:1; Eph. 5:18–21; Col. 3:16). This is an especially important instruction to consider as part of the Christian whole-life philosophy.

Here’s the question: Why would Christians be instructed to sing songs of praise and to consciously express thanksgiving to God, even in the midst of trials, difficulties, and uncertainties? The answer: Because the Christian philosophy understands the complex relationship between our minds, bodies, actions, and emotions. In line with the thoughtful Aristotelian tradition on emotions, the Old and New Testaments teach people to act in certain ways, knowing that cognitive and volitional choices not only reflect our emotions but also affect and educate them. As we engage in certain practices, both individually and corporately, they shape and form us. The liturgies and habits of the church educate our emotions in certain ways, giving articulation to and expression of certain emotional states, carrying us along with them even while our emotions may be more or less disordered and inadequately trained. We are commended to do things that include and are motivated by particular emotions, because there is a place for duty on the way to virtue. We educate our emotions through action, eventually finding the wholeness of body and soul.

In London in 2014 a group of more than three hundred people interested in Stoicism as a philosophy of life gathered together for the first “Stoicon.” As the organizers noted, this was probably the largest gathering of Stoics in over two thousand years, if not ever! The conference has continued in various cities ever since, including the special location of Athens for Stoicon 2019. Stoicon is organized by the nonprofit group Modern Stoicism, one of a number of groups and websites, such as DailyStoic.com, that are promoting the rediscovery of Stoicism to help people live in the modern world. As Daily Stoic describes it, this is a philosophy “for those of us who live our lives in the real world”—not high-brow speculative stuff.10

An internet search of “Stoicism” will result in not just translations of classic Stoic works by Epictetus, Seneca, and Marcus Aurelius but also a slate of modern books promoting the rediscovery and application of Stoicism for today’s readers. These books, sites, newsletters, and conferences offer practical advice on mastering one’s emotions, learning to meditate morning and night, and practicing certain virtues. You can even buy attractive brass coins that contain artistic images and Latin sayings like memento mori (remember your own mortality) and premeditatio malorum (premeditation on evils/misfortunes) that remind owners of key Stoic ideas (see fig. 12).

Figure 12. Stoicism coins, used by modern practitioners to remind them of core Stoic practices such as amor fati and premeditatio malorum [Photo by Brian Renshaw]

Modern life is filled with stresses, anxieties, disappointments, frustrations in relationships and work, and fears about the future. Health scares, worries about the safety of our children, pain in marriage, job loss—all of these situations evoke many emotions that can be overwhelming. Stoicism’s practical habits of focusing our energy only on what we can control—our choices and our emotional responses—are very helpful. I’ll go out on a limb and say that I think Stoicism is probably the second-best philosophy available to humans because of its emphasis on being centered, emotionally stable, and developing constructive virtues. If I weren’t a Christian, I would buy the coins, practice the morning and night meditations, read books like Donald Robertson’s How to Think like a Roman Emperor and Ryan Holiday’s The Obstacle Is the Way, and seek to live by educating my emotions through Stoic practices.

I still do a lot of those things. But I believe there is a philosophy of the emotional life that is more comprehensive and effective than even the best of Stoicism—the Christian philosophy. And beyond practicality, the Christian philosophy also has the distinct advantage of being true—rooted in the historical and theological reality of the incarnation, life, death, resurrection, and ascension of Jesus. It is a philosophy for the whole of life rooted in a metaphysic more comprehensive than Stoicism.

The Christian philosophy is indeed “for those of us who live our lives in the real world.” It is a religious philosophy that includes divine revelation and revealed ethics. Christianity has nuanced, complicated, and lofty theological constructs. But for all that, it is no less practical when it comes to our complex emotional lives. Indeed, because of its height, depth, and complexity, the whole-life Christian philosophy provides a robust and far-reaching practical approach to our emotions.

So let’s drill down into the practicality of the Christian philosophy of emotions. We can summarize Christianity’s practical advice on emotions with two habits to develop and practice. If I were to make two “Christoicism” coins for sale, they would have these two words on them—“Reflection” and “Prayer.”

Reflection. As in Stoicism and all good philosophies and therapies, the Christian philosophy holds that our minds need to be intentionally engaged for growth, healing, and happiness to occur. To philosophize is to learn to love wisdom. This occurs in the circular dialogue between thinking and practice, between learning and trying. Key to all of this is the habit of intentional reflection.

We can take an appreciative look at the Stoics’ playbook. The Stoics taught and practiced that essential to living a balanced and happy life was the practice of reflecting on what is true. Each morning a good Stoic will think about what they might face that day and role-play how they could approach a situation so as to not get hooked emotionally. Comparably, at night a Stoic will conclude each day by reflecting on ways he or she could have been more virtuous and could have been more reflective and wise. All of this is soaked through with regular meditation on the fragility of one’s own life and even intentional meditation on misfortunes to fortify resolve to live each day fully (premeditatio malorum). Many such practices are utilized today not just by adherents of modern Stoicism but also by therapists and life coaches. And they generally help people.

The good in this kind of intentional reflection is that, as Socrates famously said, “The unexamined life is not worth living.” This is because without intentional reflection, we will live our lives without direction and purpose. Or worse, we will live with misdirected and distorted goals. Reflection and meditation are essential to living well because they educate our emotions in robust and healthy ways, providing the nutrients to our soul’s emotional soil.

When we turn to the Bible, we see that Christianity encourages a comparable but superiorly shaped version of such reflective practices. Examples of intentional reflection abound. Immediately after the great Shema is given (Deut. 6:4–5), God’s people are instructed to regularly reflect on these truths, remember them, and teach them to the next generation verbally and with symbolic reminders: “Impress them on your children. Talk about them when you sit at home and when you walk along the road, when you lie down and when you get up. Tie them as symbols on your hands and bind them on your foreheads. Write them on the doorframes of your houses and on your gates” (6:7–9).

This habit of intentional reflection has a shaping effect on the belief, faithfulness, obedience, and thereby emotional health of the Israelites. The book of Psalms, which is the epicenter of the Bible’s emotional education, begins with a remarkably similar vision. Psalm 1 starts with a vivid image of what kind of people are truly happy and flourishing (a fruit-bearing tree planted by streams of water, 1:3) versus those whose lives end up in regret and loss and destruction (chaff in the wind, 1:4). One is clearly the Good Life and the other is not. What is the difference? The happy are those who meditate or intentionally reflect on God’s ways and instructions day and night, a delightful endeavor (1:2). The opposite of this kind of life of reflection is the life of being carried along with the activities of the wicked (1:1). Intentional reflection directed toward God is the difference.

Psalm 1 directly feeds into Jesus’s own teachings on true happiness in the Beatitudes (Matt. 5:3–12). With variations on the same tune, Jesus defines true happiness as found in certain ways of seeing and being in the world centered on his revelation of the kingdom of heaven. Once again, this happiness and subsequent life of discipleship depends on learning to reflect on the true nature of reality as taught by Jesus. Our emotions and our behaviors are educated by particular reflections.

The whole of the Sermon on the Mount invites us into seeing and being in the world through reflection. But even more specifically, Jesus addresses particular emotions and provides a pedagogy of our emotions through God-directed meditation. In Matthew 6:25–34 Jesus focuses our attention on one of the most powerful and destructive human emotions: anxiety. He knows the natural human propensity to worry, and he addresses the most fundamental human anxiety—the daily sustenance of food, water, and clothing. These are but examples of all of the anxieties we face in daily life. Jesus says plainly and triply, “Do not worry” (6:25, 31, 34). On what basis, Jesus? Is the solution to anxiety found in the advice of Bobby McFerrin’s affected reggae-style song “Don’t Worry, Be Happy”? Is that Jesus’s method?

No, Jesus’s practical advice for dealing with anxiety is not a denial of the reality of problems (Buddhism’s solution), nor detachment from the uncontrollable world (Stoicism), nor blithe whistleable songs (McFerrin), but intentional reflection on what is true. Particularly, the focus of this directed reflection is on the Father God, who is willing and able to provide for his children’s needs. The heavenly Father knows that we need certain things, and there is ample evidence of his care and provision in the world of flowers and birds around us. The practice of intentionally reflecting on these truths does not magically make all anxieties disappear, nor does it deny the ongoing reality of negative emotions in our human, limited lives. But it does provide a practical means by which we can educate our emotions.

Other examples abound in both the Old and New Testaments, such as Philippians 4:8, which sums up succinctly the way of being Christian in the world: “Finally, brothers and sisters, whatever is true, whatever is noble, whatever is right, whatever is pure, whatever is lovely, whatever is admirable—if anything is excellent or praiseworthy—think about such things.”

Prayer—Confession and Supplication. The discussion of how Jesus instructs us regarding anxiety leads naturally into the second practice of emotional education in the Christian philosophy—prayer, both confession (seeking forgiveness) and supplication (making requests). Herein lies a crucial difference between the Christian philosophy and all others—the fundamental belief that there is a God who is personal, relatable, capable, and kind. This God, first revealed to the patriarchs and then finally manifested through Jesus, invites people into a covenantal relationship of love. Prayer in the form of both confession and supplication is central to this relationship.

By way of contrast, for Stoicism, Buddhism, or any of a variety of other philosophies that offer practical guidance on how to live well, ultimately one’s own self-sufficiency is the core and foundation. This is why the massive genre of books in this area is called self-help. Books of this genre at the airport or your local used bookshop all say the same thing: ultimately, it is up to you to find happiness, health, and peace. For the Stoics, this is most explicit: self-sufficiency is the goal—dependence on no one and no circumstance is required for your happiness. The only way to find ataraxia and eudaimonia is to limit your emotional responses and learn to focus only on your own virtue, not circumstances that are out of your control.

There is a lot of truth in this advice, and indeed countless people have been helped by some version of this counsel. I often tell my children the same. When they are agitated with someone else or worried about some potential problem, I often remind them that they can’t control anyone else’s actions or responses, but they can and should pay attention to their own choices and emotional health.

But the Christian philosophy offers so much more, rooted in its theological metaphysic of belief in a personal and capable God. Prayer in the form of confession and supplication adds the active ingredient into a life of emotional vibrancy and health. Through confessional prayer, Christianity is able to deal with some of our most devastating emotions—shame and guilt. These powerful and destructive emotions are an inevitable part of the human experience. But other philosophies have no clear way to deal with the devastating power of these emotions other than denying that they are real or trying to talk oneself into a place of acceptance of our limits and responsibilities, or both.

Christianity acknowledges that guilt and shame are real emotions and are based on moral realities—that there is a Good coming from the true God and that it can be violated, resulting in both guilt and shame. And then Christianity provides a powerful means by which to face the reality of these damaging emotions and receive release from them, not through denial or self-help talk, but through repentance and forgiveness. Other philosophies’ approach to guilt and shame is akin to turning up the radio and putting electrical tape over the check engine light when your van is making horrible noises. Christianity handles guilt and shame the way a surgeon handles a cancerous tumor—by cutting in and cutting out to provide full healing. This happens through prayers of confession.

When King David seduced Bathsheba and then had her husband Uriah killed, this once joyful and wholehearted man of God found himself depressed, numb, and drained of emotional and physical energy. He was burdened with guilt and shame that he could not face in himself, though its effects were felt: “When I kept silent, my bones wasted away through my groaning all day long. For day and night your hand was heavy on me; my strength was sapped as in the heat of summer” (Ps. 32:3–4).

When he was finally confronted by the prophet Nathan, David broke down and confessed his sin (2 Sam. 12:1–13). The result was emotional release, healing, and restoration of balance and psychological health. He describes the forgiveness he receives as happiness/flourishing and the cause for rejoicing: “Happy is the one whose transgressions are forgiven, whose sins are covered. Happy is the one whose sin the LORD does not count against them and in whose spirit is no deceit. . . . Rejoice in the LORD and be glad, you righteous; sing, all you who are upright in heart!” (Ps. 32:1–2, 11, my translation).

Another form of prayer—supplication—also plays an important part in Christianity’s philosophy of emotions. Once again we can helpfully compare the Bible’s vision to that of Stoicism. The genius of Stoicism is that it is indeed very freeing to let go of the expectation that circumstances will provide our happiness. Happiness is found in managing our emotional responses, not the circumstances themselves, Stoicism says. As we have noted earlier, there is a disagreement here between the Stoics and their predecessors in the Aristotelian tradition. Aristotle argued that our circumstances, our Fortune, are a factor in our happiness. Emotions can and should be educated, but there is a reality to the fact that some people have better lives than others, and this does inevitably affect happiness.

In this, Christianity aligns more closely with the Aristotelian tradition than the purely Stoic, yet once again with an important nuance. It is true, according to the Bible, that our experiences and our circumstances have an effect on our happiness. God cares about our happiness and continually promises provision and a space and time when the world will be set right, when death, destruction, pain, and tears will be removed. This is envisioned in the Old Testament, with a shadow of its reality at the height of King David’s and King Solomon’s reigns. But things fall apart, always. And in the case of Israel, completely. The prophets increasingly look forward to a time when God would restore the world. This is Christianity’s understanding—that this restoration of God’s complete and perfect reign upon the earth has been inaugurated and guaranteed through Jesus’s life, death, and resurrection. This is what all the “kingdom of God” talk in the New Testament is about. There is a time and place of perfect circumstances coming, resulting in perfect shalom for God’s people. Our future is not to reach a state of enlightenment that supersedes our circumstances—disconnected from reality—but for God to bring peace and flourishing to the real world.

Christianity is a forward-looking faith that sees ultimate human happiness as something that will occur fully in the future, because God himself will vanquish all evil and be fully present with his creation. So circumstances do matter. Denial and escapism are not the solution. At the center of the greatest Christian prayer, the Lord’s Prayer, is the supplication for God to come and set the world to right, for the heavenly reality to become the earthly reality:

Our Father who is in heaven,

Let your name be sanctified,

Let your will be done,

As these are in heaven, let them be also on earth. (Matt. 6:9–10, my translation)11

And yet at the same time, Christians can and should learn to rejoice, to know joy and peace and flourishing, even when circumstances are not conducive. How? Through prayers of supplication, offering ourselves to God and asking him to provide and care for us. Through prayerfully entrusting our lives and circumstances and emotions to a personal God who is both compassionate and capable, Christians can find emotional health. A great example of this is found in Peter’s words to anxious Christians: “Cast all your anxiety on him because he cares for you” (1 Pet. 5:7). God cares. And he is also capable. God’s “mighty hand” will lift his people up in due time (5:6). Christians can do more than just tell themselves that everything will be fine. Christians can do more than just tell themselves that circumstances don’t matter. Real situations affect us. The great Christian hope is that we can supplicate. We can ask a compassionate, personal, and capable God to intervene, help, provide, and deliver.