Humans, We Have a Problem

While standing in line at my neighborhood Lowe’s to buy some deck-building materials, an item unexpectedly caught my eye. Amid issues of Fine Woodworking and Creative Gardening was a magazine entitled The Happiness Formula: How to Find Joy & Live Your Best Life. I had to buy it, even at the ridiculous price of $12.99. The magazine is a glossy ninety-five pages of articles, pro tips, charts, and graphs about the “science of happiness.” In short, snappy prose, they tell us how “modern science” (by which they mean the branch of psychotherapy called positive psychology) teaches us what things to do and not do to be happy. Eat right. Avoid bad relationships. Ride bicycles more, like the happy Swedish people do. Practice yoga. Even a home improvement store is offering help on the happiness question.

And why not? After all, this is what it means to be an American. It’s right there in our Declaration of Independence. The great American experiment was self-consciously rooted in the French Enlightenment view of humanity—that all humans are created equal, with inalienable rights. Among these rights a big three are stated explicitly—“Life, Liberty and,” wait for it, “the pursuit of Happiness.” I’m not being snarky. There are plenty of problems with the French Enlightenment and with American culture, but they’re onto something here that is bigger than France or the United States. The desire for happiness is universally human and not wrong.

But humans, we have a problem. I don’t mean the big issues that fill our newsfeeds and spark heated debates—racial tensions, social and economic inequity, definitions of sexuality, polarized political parties, even global pandemics. These are real issues, but they’re not the human problem I’m talking about.

I’m talking about a wider, deeper, and older problem that can be boiled down to the question of meaningful happiness. Does any of what we do really matter? Does it have ultimate and lasting meaning? And will this meaningfulness make me happy? These are not just the musings of nineteen-year-olds in their first philosophy class but are questions that all humans eventually ask themselves. And it’s not just a modern existential question. The Old Testament book of Ecclesiastes records the exact same wrestling by an ancient Near Eastern guy.

The fact that we all eventually ask that question shows there’s something to it. So then we must ask, How do we live meaningful lives? How do we find and maintain true happiness? This is the question at the foundation of human experience. Without meaning, life is not worth living. Only humans die by suicide.1 Even many who do not choose to end their own lives eventually feel like the philosophical superhero Deadpool, who remarks sardonically, “Life is an endless series of train wrecks with only brief, commercial-like breaks of happiness.”2

Saint Augustine, like countless thinkers before and after him, traced the essence of human meaningfulness to true happiness. When we talk about meaningfulness, we’re talking about the universal human drive to be truly and lastingly happy. Book 10 of Augustine’s massive tome The City of God begins this way: “It is the decided opinion of all who use their brains, that all men desire to be happy.”3 Happiness is what all humans want; people cannot not want happiness. This is what it means to have a brain. This is what it means to be human.

The Greeks had a word for this ultimate meaningfulness: eudaimonia, which we can translate as “soul happiness” or “flourishing.” In his five-hundred-page scholarly work on the topic, Happiness: A History, Darrin McMahon discusses Herodotus, who wrote the first history of the West. Herodotus’s grand story is set as a quest for happiness, which can be described with several Greek words—makarios (happy), olbios (prosperous), and eutychia (luck). But finally Herodotus uses the word eudaimonia—soul happiness, flourishing—to capture the subtleties of all these ideas.4

But even though the great Greeks have given us a word for true soul happiness, that doesn’t mean it is easy to find it and keep it. Moreover, happiness is not only difficult to find and keep, but it’s not even clear exactly what soul happiness is. Augustine continues his City of God discussion: “But who the happy ones are, or how they become so, are questions about which the weakness of human understanding stirs endless and angry controversies.”5

In other words, everyone who has pondered the big questions of life agrees that meaningful happiness is the goal. What people vary wildly on is what this happiness looks like and how to obtain it. For some it is a religion of duty and sacrifice. For others it is freedom from any constraints or commands. For some, happiness is found in family, friends, and food, in being aware of the goodness and beauty of such things in the moment and in memory. For others achievement, honor, success, and wealth appear to be the way to capture the elusive happiness. But we’d all agree that even though the desire for happiness is universal, it’s incredibly difficult to find and maintain. Humans, we have a problem.

In his international bestseller Sapiens, Yuval Noah Harari traces human history over what he understands to be a two-and-a-half-million-year process of evolutionary biology. He’s writing a large-scale history not just of human civilization but of the human species itself. Homo sapiens—that’s us—are simply an “animal of no significance” that has ended up dominating over other genera of animals.6

According to Harari, in the unpredictable and uncontrollable process of evolution, Homo sapiens went through three revolutions that enabled us to outlast the others and to have a place in the earth’s ecosystem that is so advanced that we can even write books about ourselves. Harari describes the three Homo sapiens revolutions as the Cognitive, the Agricultural, and the Scientific. We rule over the world (for the most part) because we alone among animals can believe in things that exist only in our imaginations—mental realities such as gods, money, nation-states, and rights.

After hundreds of interesting pages of broad-brush discussion, Harari brings his discussion down to two specific points. One is his ponderings about the future of our species in light of genetic engineering and cybernetic enhancements. The other is the question of happiness. His penultimate chapter is entitled “And They Lived Happily Ever After.” Harari states the problematic question well:

The last 500 years have witnessed a breathtaking series of revolutions. The earth has been united into a single ecological and historical sphere. The economy has grown exponentially, and humankind today enjoys the kind of wealth that used to be the stuff of fairy tales. Science and the Industrial Revolution have given humankind superhuman powers and practically limitless energy. The social order has been completely transformed, as have politics, daily life and human psychology.

But are we happier? Did the wealth humankind accumulated over the last five centuries translate into a new-found contentment? . . . [Has the] Cognitive Revolution made the world a better place to live in? Was the late Neil Armstrong, whose footprint remains intact on the windless moon, happier than the nameless hunter-gatherer who 30,000 years ago left her handprint on a wall in Chauvet Cave?7

Are we happier? This is the question we can’t avoid, nor should we. Harari’s short answer is no, in fact, we don’t seem to be happier today, though he notes this is a very difficult thing to assess historically. We simply don’t know whether a medieval peasant was happy. We can’t just project our own life experiences and expectations onto someone else’s and assume we can evaluate what they thought of their lives. By our culturally conditioned standards we can’t imagine a peasant being happy, but that’s making a big assumption. Discerning happiness depends on how we define it. If happiness is measured by material metrics such as diet, wealth, and longevity, as if these guarantee happiness, then modern humans must be happier than our predecessors. But it is not apparently the case that moderns are happier.

The real issue, Harari notes, is our tendency today to define happiness as a kind of emotional mathematics: we are happy if the sum of our more pleasant moments is more than the sum of our unpleasant ones. The average person today has been enculturated to think this way, defining happiness in terms of mere emotions. Instead, as Harari rightly points out, true “happiness consists in seeing one’s life in its entirety as meaningful and worthwhile.”8

There it is. Happiness and meaningfulness entail each other. Whether one interprets caring for a crying infant in the middle of the night as “lovingly nurturing a new life” or as “being a slave to a baby dictator” depends on whether we evaluate our actions as meaningful. And if what we do is meaningful then we can find soul happiness / eudaimonia even in the midst of hardship.9

In another recent bestseller, All Things Shining, the philosophers Hubert Dreyfus and Sean Dorrance Kelly open with these striking lines: “The world doesn’t matter to us the way it used to. The intense and meaningful lives of Homer’s Greeks, and the grand hierarchy of meaning that structured Dante’s medieval Christian world, both stand in stark contrast to our secular age. The world used to be, in its various forms, a world of sacred, shining things. The shining things now seem far away. This book is intended to bring them close once more.”10

There it is again: “intense and meaningful lives” and “the grand hierarchy of meaning”—or as they describe it memorably, “shining.” They are talking about happiness. Dreyfus and Kelly’s subtitle is important: Reading the Western Classics to Find Meaning in a Secular Age. We are now in a secular age, the authors note, an age when neither the polytheism of the ancient Greeks nor the monotheism of the Christian world holds sway. And the result, Dreyfus and Kelly readily admit, is that it is very hard to find meaning, to figure out how to live a meaningful life.

Dreyfus and Kelly are more pointed and philosophical than Harari in their assessment of happiness: We modern humans are in an existential crisis, they argue. Nihilism—the understanding that nothing really matters—is the air we breathe in the modern secular age. And this is bad news for humanity.

Humans today, especially in the West, live in a psychological space where the old structures, both pagan and Christian, have broken down and been replaced with a scientific understanding of the world. This enables us to send a probe to Saturn but find it difficult to live meaningful lives. While most people walking around aren’t committed nihilists—this is more often the felt experience of artists and philosophers—they struggle to find a comprehensive worldview that makes life meaningful. It is hard to be happy. If it weren’t, we wouldn’t have 577,000 mental health professionals, 15 million people suffering from depression, and a $10 billion industry in bibliotherapy (self-help books). This is just in the United States alone.11

Harari, Dreyfus, and Kelly are all philosophers trying to help us understand life. Whether they realize it or not, they are standing on the shoulders of the giants of a tradition of human-helping that goes back as far as human civilization itself.

It turns out that the question of meaningful happiness and how to find it is not new. It is not just a function of modern humanity’s experience. It is as old as thinking humanity itself. Remember Augustine’s comment about the drive for happiness? He wrote that in the early 400s AD. By that time, the philosophical discussion about happiness and meaning was at least seven hundred to eight hundred years old in the Western tradition and even older in the ancient Near East and Far East. In the Greek and Roman tradition, thinkers we’ve met already, like Socrates, Plato, Aristotle, Epictetus, and Seneca, all pondered the great questions of happiness and offered practical, real-life wisdom on how to live well. The nineteen-year-old students pondering this in their philosophy class are onto something important and deeply human. They’re thinking about the right question. The “sapiens” part of our Homo sapiens designation refers to “wisdom” (Latin, sapientia). What distinguishes our version of creatureliness is our thinkingness, our insatiable pursuit of understanding, of meaningfulness.

Throughout this book we’ve met several ancient philosophers, and we’ve seen that they were thoughtful, sophisticated thinkers who cared about real, practical life. They developed schools of philosophy and made evangelistic disciples not so they could get cushy professorial jobs (well, at least not the sincere ones) but so that they could help themselves and other people learn how to live well. So all their explorations about physics, metaphysics, ethics, politics, emotions, and relationships funnel down to this greatest of human questions: How do we find meaningful happiness? Everything else the ancient philosophers talked about always had this human flourishing goal as the ultimate purpose.

We don’t need to rehearse what Plato, Aristotle, Epicurus, and Seneca said about emotions and relationships. We do need to close the loop on our reflections by recognizing how this is all connected to meaningful happiness.

The reason these thinkers thought so much about emotions, the importance of friendships, the role of the government in relationship to the individual, and how to handle anxiety is because (1) they knew that the drive for flourishing was central and universal to human experience, and (2) they knew that learning to order our emotions and relationships is crucial to our meaningful happiness.

For the Greek and Roman tradition—the notable exception being the hedonists—the flourishing and happy life does not happen accidentally. It must be sought after. And the means of pursuit is the life of discipleship to a philosophy, a way of seeing and being in the world that is pursued and practiced. First become aware of yourself; then turn away from foolish and non-life-giving habits and thoughts (in biblical language, “repent”); and then, over time, learn new ways of living through failures and successes in practice.

There were differences, certainly, between what Aristotle, Epicurus, and Marcus Aurelius said about all kinds of issues. They didn’t agree, for example, on what role physical pleasures played in true happiness. And Aurelius, following good Stoic practice, meditated each morning on all the bad things that might happen to him. There’s no indication this habit would be recommended by Aristotle. These differences in philosophy and practice are inevitable because each of their teachings was tied to their own understanding of the world that affected how they practiced life. Also, each person’s life experience is different. As the old saying goes, “All theology is autobiography”—so too with the ancient philosophers. Why we are inclined to think and practice life in certain ways is always embedded in our own particular experiences.

So they disagreed on lots of habits and beliefs, but they all shared this central idea: We long for flourishing, and the only way to find it is through living intentionally and thoughtfully in particular ways. Neither virtue nor its eventual fruit, happiness, comes to us accidentally.

Even though today’s philosophers rarely traffic in the great question of happiness like their predecessors did, this doesn’t mean we’ve stopped having happiness-purveyors. We have lots of them. Even if most professional philosophers have abdicated this role, humans, like water obeying gravity, will always find gurus to guide us to happiness.

Today we have countless happiness gurus of all sorts, shapes, and sizes. Most are sincere and helpful; some are manipulative and malignant. A lot of them provide some help. Some provide a lot of help. And some of them provide good help that is misapplied by bad people. The story goes that while in prison for car theft, Charles Manson read and became obsessed with Dale Carnegie’s famous self-help book How to Win Friends and Influence People. Just over ten years later, having founded a California cult centered on himself, he influenced his “family” to commit atrocious murders.12 No one is happy with Manson’s particular application, but all agree that Carnegie is an example of a guru of meaningful happiness.

I wrote much of the last half of this book in the beautiful new, modern, angular glass-and-steel Northeast Regional Library that’s within walking distance of my house. Even in the modest holdings of this library are several rows of books designed to help people figure out their lives and how to be happy. Titles include Lagom: The Swedish Art of Balanced Living, You Are the Placebo, 10% Happier, Stick with It, The Happiness Equation, and The Secret (which obviously must not be so any longer). These are just a few random titles that I see as I walk by those shelves during my intralibrary circumnavigation break. Let’s take a brief walk through a couple of the myriad of happinesses on offer today.

A good place to start is with Alain de Botton and his School of Life. I first encountered de Botton when devouring his beautiful and fascinating book Art as Therapy. This handsome volume (you should spend a little more and get the hardback) is full of images of art and architecture. This remarkable book resists classification. At first you may think it is just a pretty art-history coffee-table book, but soon you realize much more is going on as it moves quickly and digs deeply across a wide range of psychological, personal, and social issues. You’ll be forced to think profoundly, and not just about lofty ideas. You’ll soon be pondering your feelings of anxiety, envy, and what it means to love. I’ve gone on to read several other books by de Botton, who really is a twenty-first-century version of an ancient philosopher. Today this comes complete with all that modernization means—many published bestsellers, TED talks, YouTube lectures, and even a BBC Channel 4 series on philosophy.

What ties Art as Therapy together is the conviction that our intentional engaging of visual art can help us lead better lives. For de Botton (and his coauthor, John Armstrong) this means accessing “better versions of ourselves.”13 The great function of visual art, they argue, is to use it as a tool for our therapy. This therapy is our growth to becoming better versions of ourselves through being guided, exhorted, consoled, and enabled by what art offers.14 Visual art, when interpreted soul-therapeutically, helps us with our psychological frailties and needs. Art channels to us the importance of remembering, hope, sorrow, self-understanding, growth, and appreciation. Art helps us with our most intimate and ordinary dilemmas.

De Botton and Armstrong are using art and architecture to consciously address the great human questions of happiness and meaning. Their book is only one part of a larger project they are engaged in called the School of Life. The School of Life is, according to its website, “a global organisation dedicated to developing emotional intelligence” through applying psychology, philosophy, and culture to everyday life.15 This philosophy of emotional intelligence is worked out through the production of books like Art as Therapy and also through a wide range of human development workshops conducted by experts all over the world, centered in these city-based schools. Sounds a lot like ancient Greek philosophy.

One such workshop is entitled “Finding Meaning without Religion.” Quite similar to Dreyfus and Kelly’s All Things Shining, this workshop starts with the recognition that modern people (at least in the West) have the freedom to choose religion or not. No single religion or philosophy dominates our culture now, unlike before. This has its downside, the seminar notes, because we are conscious of a “God-shaped hole”—a sense of a higher purpose—that we aren’t sure what to do about with no authoritative answer.16

De Botton has written a whole book along these lines, with the intriguing title Religion for Atheists. He is a committed atheist and makes this clear on page 1. He doesn’t believe in miracles or “tales of burning shrubbery.” But unlike most intellectual atheists, de Botton is not content to focus only on critiquing religions for their problems and irrationalities. Quite the opposite, he is interested in helping his fellow committed atheists rediscover that organized religions contain human thoughts and practices that can be useful, interesting, and even consoling. According to de Botton, even though the doctrine of the Christian Trinity or the Buddhist Eightfold Path can leave one cold, there are many ways in which religions help humans live morally, develop community, and inspire us to appreciate beauty—to live the Good Life. Atheists have a lot to learn from religions, he says.

De Botton states that our predecessors invented religions to serve two central needs: (1) the need to live together in communities in harmony even though we are deeply selfish and at times violent, and (2) the need to cope with fear, pain, difficulties, and ultimately death. Even though de Botton rejects the truthfulness of any religious claim, he notes that these two issues still exist in our secular society and that we’ve not done a particularly good job of developing skills to deal with them. Once we get free from the compulsion to worship gods or to denigrate them, then “we are free to discover religions as repositories of a myriad of ingenious concepts with which we can try to assuage a few of the most persistent and unattended ills of secular life.”17 These “ingenious concepts” include the notions of community, kindness, education, institutions, art, and architecture.

De Botton is a clear and fascinating writer. His insights are noteworthy, stimulating, and memorable. This includes lots of quirky but profound graphics, such as the chart comparing Pringles sales to the number of poetry books sold in a given year. Religion for Atheists, Art as Therapy, and the School of Life all promise the way to a meaningful life. De Botton’s philosophy of life is far more sophisticated and helpful than slapping a “Coexist” bumper sticker on one’s car, whether aggressively or peacefully. From a Christian perspective, the ultimate question of what is true is still unavoidable. Nonetheless, de Botton exemplifies thoughtful humanity wrestling with the universal questions of how to find and live meaningfully happy lives.

Top-ten movie lists are dangerous things to offer—so I won’t—but I will say that for me, somewhere in that enumeration is one you probably haven’t heard of: Hector and the Search for Happiness. Rotten Tomatoes and other rating systems generally rank it pretty low, so you’ll have to decide for yourself, but I love it. It’s a 2014 movie starring Simon Pegg, based on a French novel of the same name by François Lelord.

Hector is an English psychiatrist who lives a very safe and organized life but who increasingly realizes he is not happy. He also realizes he’s not really helping his clients become any happier. So, uncharacteristically, he sets out on a quest to discover happiness. His journey takes him to China, where he experiences both the high life in an exclusive nightclub and the deep inward journey with Himalayan monks. He visits an old friend in Africa, eventually being ambushed and left to suffer in a rat-infested prison. Finally, he goes to California to try to reconnect with the college lover that he let get away. In all of these situations he both suffers and finds moments of joy. But deep and lasting happiness remains elusive, even while his relationship with his longtime girlfriend in London is deteriorating.

Finally, while in Los Angeles, Hector meets a professor who lectures on happiness and is doing brain-scan research on emotions. Professor Coreman asks the haunting question, “How many of us can recall a moment when we experienced happiness as a state of being, that single moment of untarnished joy, that moment when everything in our world, inside and out, was alright?” It’s elusive, isn’t it? His conclusion is that “we should not concern ourselves so much with the pursuit of happiness, but with the happiness of pursuit.”18

Spoiler alert: Stop reading now if you don’t want to hear about the climactic moment. The movie ends with Hector in the neurologist’s booth experiencing a block—he can’t feel anything. He is directed to think about times he was happy, sad, and scared. He can recall memories, but he can’t connect to his emotions. And then, finally, he breaks, and the scans explode with color and activity. He finally discovers that happiness is found not just in one positive emotion but in embracing all of his emotions and experiences. It’s a very powerful scene that never fails to make me cry.

Along the journey before this point, Hector scribbles his reflections on happiness in his notebook. The result is a list of eighteen insights about happiness. It is this potentially pedantic technique that has made some readers of the novel feel it is more of a “maudlin self-help guide” than a story.19 That may be more true of the novel than it is for the movie. Nonetheless, these eighteen tips provide a guide for human happiness, very much like the Stoics and other ancient philosophers provided.

Here are some of them:

- Making comparisons can spoil your happiness.

- Avoiding unhappiness is not the road to happiness.

- Happiness is answering your calling.

- Happiness is being loved for who you are.

- Happiness is knowing how to celebrate.

- Nostalgia is not what it used to be.

Once again we find ourselves on a quest for happiness. Life is complex and difficult. We instinctively know there is an elusive happiness out there—we’ve tasted it more than once. How do we find it? Are pithy aphorisms the solution?

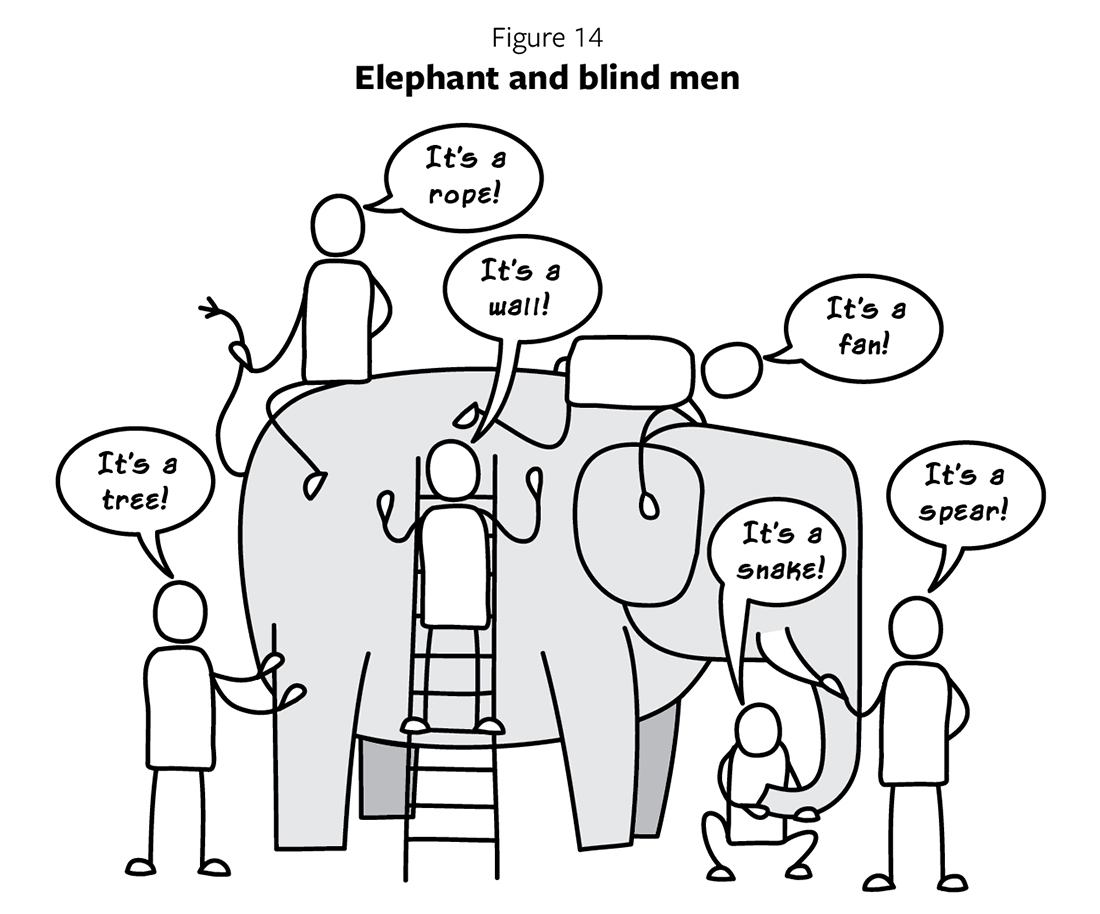

Anyone who has ever had a class on world religions or gotten into debates online about the exclusiveness of various faiths has probably eventually run into the “blind men and the elephant” illustration. The story goes something like this: There are several blind men walking together, and they encounter an elephant. Because they are blind and each only experiences part of the elephant, they all have different interpretations. Feeling the tusk, one says it is a spear. Encountering the trunk leads one to believe it is a snake. A rope or tree are the natural interpretations for those feeling the tail or legs. Who is right? Well, none of them and each of them. Each blind man—like each religion—only sees a part of the truth. And from the limited part they see, they make a reasonable interpretation, so the story goes.

So too with the seemingly infinite number of philosophies of happiness. Just in the ancient world alone, people disagreed significantly about how to find flourishing. Do we need to detach ourselves from emotions, or is the key ecstatic temple-based experiences? When we follow human thought down to today, the differing philosophies of life-happiness are myriad and overwhelming. Is it a keto diet, CrossFit, entrenching into “Make America Great Again” values, finding inner peace through hot yoga, daily journaling, making sure you “pay it forward” every day, etc., etc., etc.? There are simply too many choices, like the menu at the Cheesecake Factory. It can feel paralyzing.

Moreover—and partially a result of this overwhelming feeling—few of today’s philosophies are even attempting to give us something comprehensive. Most philosophies of happiness on tap are very particular in their focus and make no metaphysical claims to explain all of reality. Peloton’s quite pricey but apparently effective internet-connected bike exercise program provides an “immersive cardio experience,” but it doesn’t promise to help you figure out mothers-in-law or the fear of death. This limitedness is typical.

Alain de Botton’s School of Life is the most comprehensive nonreligious philosophy of happiness I have found today. It is modeled, at least in part, on the ancient philosophical schools, and this is no accident. Most of the gurus that people look to today offer only a limited kind of happiness—happiness in the realm of parenting, or of business sales, or in marriage, or in physical exercise. De Botton’s School of Life is the closest thing to a whole-life philosophy of happiness, but it is still limited.

So who is right? Are we all just blind philosophers encountering a part of the elephant of life with no hope of a comprehensive philosophy of happiness?