Christianity’s Whole, Meaningful, and Flourishing Life

Back at the beginning of our journey exploring Jesus as the Great Philosopher, we met one of his earliest followers, Justin the Philosopher-turned-Martyr. Justin represents the primal understanding of Christianity as a philosophy. Indeed, Christianity is the truest philosophy of the world because it is based on the person of Jesus, the incarnated Son of God.

This conviction means that, while there may be good ideas and practices that can be gleaned from other philosophies and religions, they are only partial. In comparison with the Christian philosophy, all other views on relationships, emotions, and happiness are fractional and incomplete (and sometimes just flat wrong). Or to think of it constructively, because Jesus is the actual Logos—the organizing principle of the world, the agent of creation, the being that holds the whole universe together—this means that his philosophy alone is whole, complete, and truly true. How’s that for a physic behind a metaphysic that gives us an ethic and politic?

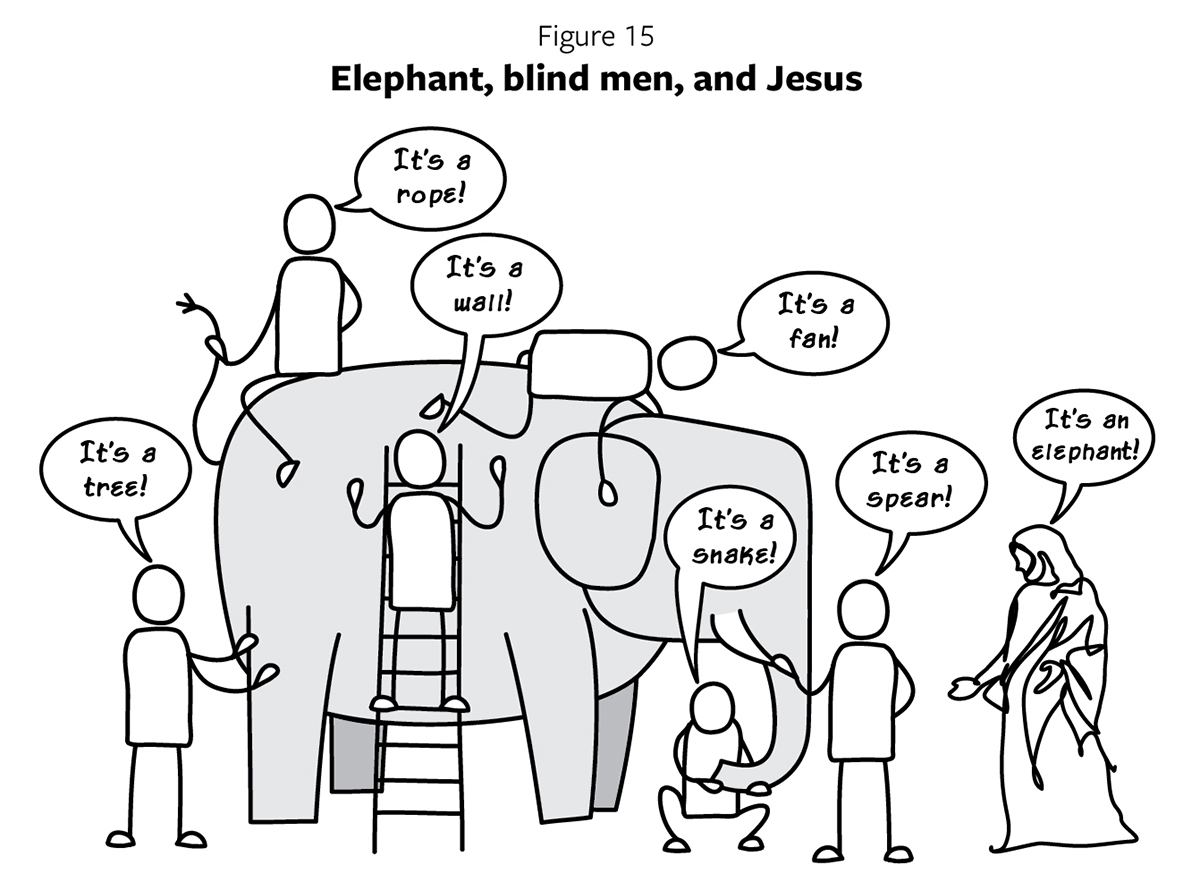

So let’s intersect this powerful truth with the famous blind men and the elephant story. Each of these blind philosophers understands to the best of their ability. But Christianity makes a claim that is inherently transcendent—Jesus is not just another wise man or insightful sage. He stands above, around, and outside of this whole philosophical elephantine situation. He alone sees the whole and sees correctly and therefore alone can proclaim truly and fully, “It’s an elephant!”

This image helpfully depicts the reality of Jesus the Great Philosopher and Christianity as the true philosophy of the world. However, this otherwise good analogy breaks down in one important way. Namely, the blind philosophers in this story are each entirely wrong regarding the actual elephant, thinking the tail is a rope, the leg a tree trunk, and so on. While this analogy works for the point of the illustration—that every religion sees imperfectly—it doesn’t quite work for what I’m trying to say. That is, Jesus’s all-seeing perspective does not necessarily mean that all the insights of other religions and philosophies are completely wrong. None of them have the complete perspective that Christianity does, but this does not mean everything they say is entirely mistaken. It only means every other philosophical view is partial.

Hence, as we have seen throughout this book, there is insight to be gained from what the philosophers said about all sorts of topics. We needn’t cut ourselves completely off from their wisdom. Rather, we can gather lumber from whatever trees are available as we build the Christ-shaped temple of our lives, with Holy Scripture as the building inspector. As Justin himself said, “Whatever things were rightly said among all men, are the property of us Christians. . . . For all the writers [ancient philosophers and poets] were able to see realities darkly through the sowing of the implanted word that was in them. For the seed and imitation that is imparted according to capacity is one thing, and quite another is the thing itself, of which there is the participation and imitation according to the grace which is from Him.”1

That last part gets a bit complex, but the point is straightforward—any wisdom in the world is from God, who created all, but we Christians have the grace that enables complete understanding. This includes the grandest human philosophical question: What does it mean to live a whole, meaningful, and flourishing life? What is the wisdom we need for the Good Life?

The monk Elder Zosima is the moral center of Fyodor Dostoevsky’s sweeping novel The Brothers Karamazov. While discussing his impending death with a noble lady, she remarks that Zosima looks so happy, despite his deteriorating health. He responds, “If I seem happy to you there is nothing you could ever say that would please me so much. For men are made for happiness. And anyone who is completely happy has a right to say to himself, ‘I am doing God’s will on earth.’ All the righteous, all the saints, all the holy martyrs are happy.”2

This sounds odd. If we conducted another “Word on the Street” interview and asked people what comes to mind for the word “happy,” I doubt many people, if anyone, would say, “The righteous, the saints, the holy martyrs”—no matter how many people we interviewed. And if we asked it in the converse way—How would you describe the righteous, saints, and holy martyrs?—I bet the responses would include adjectives like “uptight, anxious, and angry,” not “happy.” “Happiness” and “Christianity” aren’t related in our minds. They’re not even cousins.

The same could be said for “Christianity” and “philosophy.” In modern usage, these words are two different worlds, as intimately related as spark plugs and cheese. But in reality, Elder Zosima’s confident comment, the philosophical tradition of seeking happiness, and the Christian faith are all deeply interwoven. They are strands of one tapestry.

Saint Augustine said it this way: “No one has any right to philosophize except with a view to happiness.”3 Augustine understands his Christian faith to be about philosophy and about happiness. This is because philosophy, understood correctly—whether it is from Moses, Aristotle, de Botton, or Jesus—is about meaningful happiness. And if Christianity is true and significant, then it too will address this greatest of human questions.

The Polish theologian Darius Karłowicz sums it up this way: “The task of all philosophy, including Christian philosophy, is the therapy of souls who have been led astray by the demands of the passions and false pictures of happiness.”4 Christianity is engaged in the great work of reshaping humanity into the image of Christ (Rom. 8:29; 2 Cor. 3:18). This is a soul therapy that promises to bring humanity back into a life of meaningfulness. Jesus sums up his own purpose as coming into the world “that they may have life, and have it to the full” (John 10:10).

Key to this soul therapy is challenging misunderstandings about happiness that humanity has imbibed. It means guiding people to discover ways of inhabiting the world that will lead to meaningful happiness—all based on the revelation of God in Jesus Christ. Christianity is a philosophy of happiness.

Christianity is a philosophy of happiness because it is based on the Bible, and the Bible is constantly addressing these same grand questions of meaning and happiness.5 As one small window into this, we can consider the first poem of the great collection of Israel’s songs and prayers, what is called the Psalter. Psalm 1 addresses the question of meaningful happiness right out of the chute, centering happiness in a life orientation toward God:

[Happy/Flourishing] is the one

who does not walk in step with the wicked

or stand in the way that sinners take

or sit in the company of mockers,

but whose delight is in the law of the LORD,

and who meditates on his law day and night.

That person is like a tree planted by streams of water,

which yields its fruit in season

and whose leaf does not wither—

whatever they do prospers.

Not so the wicked!

They are like chaff

that the wind blows away.

Therefore the wicked will not stand in the judgment,

nor sinners in the assembly of the righteous.

For the LORD watches over the way of the righteous,

but the way of the wicked leads to destruction.

So right here in the first song that all Hebrew children and adults sing and all Christian monks and nuns chant repeatedly throughout the week and year is the issue of true happiness. The very first topic in this 150-song book that explores the full gamut of human emotions and experiences is the question of flourishing. The Bible cares about the Good Life.

This tone-setting psalm is intentionally mirrored right at the beginning of Jesus’s ministry too. Jesus’s famous Sermon on the Mount starts with his Beatitudes, his authoritative declarations about what true happiness (beatus) is. Jesus’s celebrated instructions start with exactly the same word that Psalm 1 does—“Happy/Flourishing.”6

Happy/Flourishing are the poor in spirit, for the kingdom of heaven is theirs.

Happy/Flourishing are those who mourn, for they will be comforted.

Happy/Flourishing are the meek, for they will inherit the earth. (Matt. 5:3–5, my translation)

In the Beatitudes, Jesus gives nine statements about what true happiness or the Good Life looks like now and in the age to come. In fact, in some early biblical manuscripts the whole Sermon on the Mount (Matt. 5–7) was titled “Concerning Happiness,” because it was clear to Matthew’s readers that this is what Jesus was offering. Jesus is a philosopher of happiness.

I think we can confidently say—even though it sounds odd today and could be misunderstood—that at the very core of the Bible’s message is the idea of true happiness and flourishing. “Shalom” is how the Old Testament describes it. “Flourishing” or “entering the kingdom” or “being glorified” or “entering life” is how the New Testament talks. It’s all wrapped up together, no matter which words or metaphors we use. The Bible is a book about true happiness.

Does this sound odd? This may be because you’ve been taught that longing for happiness is a bad thing. But God himself is fully happy, and as creatures who are made in his image, we long for the same. And we had it once. In the prefall garden of Eden, Adam and Eve knew God and walked with God. And they were happy. It was a false promise of more flourishing that led to humanity’s broken relationship with God and all its subsequent pain, suffering, and death. The serpent’s offering of forbidden fruit was a hook for more happiness. Satan rightly appealed to the first humans’ desire for abundant life as seen in the form of a tree. Tragically and ironically, it was this trusting of the wrong authority (Satan rather than God) that resulted in humanity’s prohibition from being able to eat of the tree of eternal life (Gen. 3:22–24)—the very thing we all long for.7 The problem was not the desire for happiness but rather the wrong way in which they pursued it.

That is a crucially important distinction. This distinction begins to address a potential big objection to what I’ve just been saying. Someone may fairly ask, “What about self-denial? What about Jesus’s call to take up our cross and follow him?” How in the world could I be saying that the Bible cares about happiness in light of this? Isn’t all this talk about happiness and flourishing just another version of the plastic-smiled and deceptive health-and-wealth gospel?

Those are fair and understandable questions. I would respond by noting that the desire for happiness is not inherently wrong. The Bible nowhere condemns the desire. Quite the opposite—the desire for happiness is assumed. But it is easy to throw the proverbial baby out with the bathwater when we see how easily and thoroughly the desire for happiness gets corrupted. We’ve all heard people appeal to their own happiness as the basis for abandoning one’s family and running off with the secretary. And we’ve heard a hundred other misappropriations. But the problem here, once again, is not the desire for happiness but the means by which it is pursued.

For countless Christians in contemporary America, speaking of “desire” and “God” in the same sentence will make us think of the great preacher John Piper. I first read his hugely influential book Desiring God shortly after it came out, when I was a fresh college-aged believer. It was transformative for me, as it has been for thousands of others. The book you’re holding in your hands is not one that I think Piper would ever write for many reasons, but I believe our projects have a deep resonance and harmony. They are written in the same key—the key of longing and desire for true happiness and flourishing. I don’t imagine Piper loves Pink Floyd as much as I do, but I think he would affirm the universal sentiment of human longing and loss expressed in their classic song “Comfortably Numb.” David Gilmour refers to his childhood as a time when he caught a fleeting glimpse of happiness, but then it eluded him. Now, “The child is grown / The dream is gone.”

Piper’s original Desiring God subtitle—Meditations of a Christian Hedonist—raised eyebrows in its day. I’m not a big fan of this subtitle because of the importance difference between hedonism and philosophy. But I appreciate what he’s getting at. Piper’s point is that not only is it okay to have desires for happiness, but happiness is also necessary for a proper relationship with God. If we approach God with duty or obligation as a primary motivation, not love and desire, then we don’t have a true relationship—we have mere religion.

Early on in his book, Piper gives a lengthy quote from the always-insightful C. S. Lewis that is worth repeating here: “If there lurks in most modern minds the notion that to desire our own good and earnestly to hope for the enjoyment of it is a bad thing, I submit that this notion has crept in from Kant and the Stoics and is no part of the Christian faith. Indeed, if we consider the unblushing promises of reward in the Gospels, it would seem that Our Lord finds our desires [for happiness] not too strong, but too weak.” This is from Lewis’s beautiful sermon “The Weight of Glory.” He goes on to famously say, “We are half-hearted creatures, fooling about with drink and sex and ambition when infinite joy is offered to us, like an ignorant child who wants to go on making mud pies in a slum because he cannot imagine what is meant by the offer of a holiday at the sea.”8

That reference to Kant is especially important and deeply relevant to the vision I’m casting here for Christianity as the true philosophy of happiness. Here specifically, Lewis, and by proxy Piper, is tapping into one of the most disastrous ideas of Kant, the notion that for an action to be virtuous and good, the agent/actor must not get any personal benefit from it. This benefit especially includes one’s own flourishing and happiness. Kant’s idea of a good action is called “altruism.”

Altruism has become so deeply embedded in modern ethics that most Christians do not realize how thoroughly unbiblical it is. And this is what Lewis and Piper are getting at. Altruism is indeed death to biblical (and ancient philosophical) ethics. Lewis’s and Piper’s point, and mine as well, is that it is precisely the desire for happiness that drives all that we do. And that’s okay. It is how God made us and exactly how God motivates us. It is the “staggering rewards” that Jesus continually promises us that are not condemned but commended. (I’m not sure Lewis is entirely fair to throw the Stoics under the bus here, but Kant definitely needs a curbside push on this matter.)

The biblical emphasis on rewards from God as motivation means that the ideas we hear from Jesus about “self-sacrifice” and “cross-bearing” must not be misconstrued. These cross-bearing commands do not mean denial of our own desires for happiness, as if somehow a duty-only approach is a virtue. Altruistic self-denial is neither a virtue nor what Jesus is saying.

The call to lay down narcissistic self-absorption and to serve others even at a cost to our conveniences, finances, and luxuries is real (Phil. 2:1–11). But this is never an appeal to abstract duty; it is instead an invitation to true happiness. “It is more blessed [the same word as in the Beatitudes] to give than to receive” (Acts 20:35) is not a Kantian statement of duty but an invitation to wisdom, to reorienting our hearts toward what will truly bring the fountain of flourishing to our dry souls. The call on our lives is not a denial of desire but a reordering of our loves for the greatest good for us, others, and God’s honor. As Lewis’s devil Screwtape explains to his tempter in training, when the Enemy (God) instructs humans to lose themselves, “He only means abandoning the clamour of self-will; once they have done that, He really gives them back all their personality.”9 Self-denial is the means to soul-fullness.

This was even Jesus’s own motivation. Jesus, the perfect human, had real desires and motives that were not merely obedient duty. He was motivated by desire. Why in the world would this sinless, beautiful, caring God-man be willing to endure mocking, misrepresentation, physical privation, and ultimately torture and death? What would make you willing to do so? Kantian duty?

No. We’re told exactly why—for the joy that he would gain and enter into as a result! Hebrews 12:2 sums it up with the invitation for us to look to Jesus’s own example here, to “fix our eyes” on him as the model and pioneer of what it means to relate to God rightly. It was “for the joy set before him [that] he endured the cross, scorning its shame, and sat down at the right hand of the throne of God.” Jesus was motivated by his own future happiness.

And now we can come full circle to our discussion of the genius of ancient philosophy. Kant’s very different approach to ethics is precisely what happened to modern philosophy to make it only “screw you up for the rest of your life,” as Steve Martin quipped. Modern philosophy is abstract, depersonalized, and doesn’t help us learn to live well. But ancient philosophy did. And so does biblical Christianity.

The ancient Christian philosophy offers a remarkably sophisticated understanding of what it means to pursue and find true happiness in this broken and disappointing world. The fact that we have stopped thinking that this is what Holy Scripture is offering is not a function of the Bible’s actual teaching but of the undue influence of this whole approach to life that modern philosophy has promoted. Thanks, Kant.

So what does this sophisticated Christian philosophy of a whole, meaningful, and flourishing life look like? As we have seen with the topic of emotions and relationships, Christianity does not offer simplistic, bumper-sticker platitudes. Instead, when we dial in on the question of flourishing in Holy Scripture, we find a robust and nuanced answer.

The Old Testament begins with a tragic two-step story of paradise made and paradise lost. Within only the first three chapters of the great Genesis creation story we see humans move from the experience of flourishing in the presence of God to shame, regret, fear, loss, and death. What follows is a story of increasing degradation, suffering, conflict, homicide, grief, humanity-massacring floods, sodomy, deceit, and rape.

Where is flourishing in all of this? It is found in glimpses when people turn to God, lifting their eyes from earth to heaven. People like Noah, Abraham, Sarah, Isaac, Rebekah, Leah, Jacob, and Rachel taste bits of true happiness in hors d’oeuvres–sized moments of faith and obedience. They briefly reflect what it means to be fully human and happy, like an image in a shattered mirror.

But this imperfect experience of flourishing in the biblical stories does not belie the emphasis that Scripture puts on true happiness. Quite the contrary, the biblical story of brokenness and sin explains why humans universally long for shalom, for a whole and meaningful life. As a result, the arc of the whole story of Israel is one of hope—certain hope for a coming age when God will return, bring justice, and establish peace throughout his marred creation and in his distorted creatures. This is the hope of the coming kingdom of God, especially highlighted in the Old Testament prophets, and most especially in Isaiah.

The book of Psalms is the divinely given songbook and therapeutic manual during this time of waiting. The Psalms embrace the reality of brokenness, longing, disappointment, injustice, and death. Yet, as we noted above, the very first word of the Psalter casts a vision for the possibility of happiness and flourishing—now and yet more to come.

This is remarkably sophisticated. The Old Testament is not an idealized mythology of easy happiness. It is not a philosophy that proclaims all suffering to be inconsequential or unreal. Neither is it a hopeless story of sin and destruction or postmodern literary antiheroes. No, the story of Israel from creation through the prophets casts a vision of the possibility of deep flourishing even in the midst of inevitable loss and suffering.

This vision serves as the essential backstory and scenery of the message that the New Testament proclaims. Jesus has now arrived to reverse the paradise lost! The promised shalomifying reign of God is finally here because the divine Son-King has returned home. This means the creation itself will begin to undergo a reversal, a reality that was first typified by physical phenomena at Jesus’s death and resurrection, the regreening of the gray world. The events like darkness at noon, the temple curtain being torn in two, and the raising of dead people from their graves (Matt. 27:45–54) are symbols of a new creation coming. This also means that humans who share in the Son’s Spirit-filled resurrection life will begin to experience a transformation away from cursedness to flourishing. The great ancient theologian Irenaeus famously described it this way: our Lord Jesus Christ “through His transcendent love became what we are that He might bring us to be even what He is Himself.”10

Jesus not only brings into being this new age of flourishing in the midst of suffering but he also models for all humanity what this can look like. Jesus was a man of joy and love and peace. Whatever medievally inspired or puritanically stern images we might have of Jesus are simply not how the Gospels portray this man, who was accused of being a drunkard and friend of sinners. He was a happy and flourishing man. But he also suffered greatly. He experienced physical pain and emotional disappointment and frustration. He died not of natural causes but of the most unnatural—torture and suffocation at the hands of his enemies. He told his followers to expect the same. Yet he also constantly invites his disciples to be happy and to rejoice. In fact, in the very same breath, at the climactic conclusion to his nine-point discourse on happiness, he proclaims that true happiness can be found when you are “persecuted because of righteousness” and when people “insult you, persecute you and falsely say all kinds of evil against you” because of your association with Jesus (Matt. 5:10–11).

So, as with the Old Testament, the New Testament offers a nuanced and sophisticated—even paradoxical—philosophy of human flourishing or the Good Life. Jesus and his followers do not deny the reality of suffering. Neither do they encourage a closed-hearted “stiff upper lip” mentality. Rather, a whole, meaningful, and flourishing life is possible in the midst of brokenness and even unjust suffering.

There is a mystery and paradox here that is beyond human comprehension, but somehow suffering can even produce a greater and truer happiness. It’s easy to fall off the knife-edge of this paradoxical truth on either side—seeking suffering masochistically or denying the divine good in difficulties. But Job and Jesus and countless other trusters in God have testified that trials, difficulties, and suffering have somehow brought about greater and deeper joy. The stars are brightest from inside the well. We may speculate that this has to do with a reorienting of our priorities and a refining of our desires for what is Good. But ultimately we must be content to embrace this truth without fully understanding it.

How is this happiness-while-suffering paradox possible? The Christian philosophy’s answer can be boiled down to one word: hope.

Hope is a funny thing. On the one hand, it is one of the three greatest abiding realities, according to 1 Corinthians 13:13: “And now these three remain: faith, hope and love.” Forward-looking hope, as prominent New Testament scholar Richard Bauckham and theologian Trevor Hart have noted, is core to what it means to be a Christian: “To be a Christian, a person of faith, we might suggest is precisely to live as a person for whom God’s future shapes the present.”11 To hope is to have faith.

Yet on the other hand, Christian hope has often been a particular point of derision from Christianity’s opponents. From ancient times until today, Christianity’s critics have often pointed to Christians’ hope for a heavenly future as obscurantism and naive escapism. Unfortunately, even some within the Christian tradition have misstepped in this way.

We see the centrality of hope as a recurrent refrain throughout Scripture. Listen to how the apostle Paul describes hope’s power and effects in the letter to the Romans:

We also glory in our sufferings. . . . And hope does not put us to shame, because God’s love has been poured out into our hearts through the Holy Spirit, who has been given to us. (5:3, 5)

For in this hope we were saved. But hope that is seen is no hope at all. Who hopes for what they already have? But if we hope for what we do not yet have, we wait for it patiently. (8:24–25)

Or consider the way the Psalms contrast two possible ways for us to live—as hoping in the people and things of this world versus hoping in God. Hope is another synonym for waiting and trusting in the Lord:

But the face of the LORD is against those who do evil,

to blot out their name from the earth.

The righteous cry out, and the LORD hears them;

he delivers them from all their troubles.

The LORD is close to the brokenhearted

and saves those who are crushed in spirit.

The righteous person may have many troubles,

but the LORD delivers him from them all;

he protects all his bones,

not one of them will be broken.

Evil will slay the wicked;

the foes of the righteous will be condemned. (Ps. 34:16–21)

So in the Bible hope is very important to happiness. The Good Life is a life of brokenness and joy, of love and loss, all empowered by sure hope.

The more personal dilemma of hope is what has been called the “eudaimonia gap.” Eudaimonia, as we discussed earlier, is the Greek way of talking about human flourishing and happiness. But there is a problem. Our experiential reality is that we long for happiness yet can never fully attain and maintain it. Even with the best practices of physical and mental health, all of our happiness gets tainted and marred and never lasts. For many people, it is wrecked by poverty, disease, violence, injustice, and brokenness. And for all people, sooner or later, this flourishing life comes to an end. As the Christian scholar David Elliot points out, “The ills which limit happiness in these ways constitute a depressing gap between the kind of happiness we want and the kind we can reliably get.” Most people, Christian or not, respond to this “eudaimonia gap” with melancholy resignation.12 Many self-medicate to avoid the existential crisis of the gap.

This is where the Christian philosophy of hope is critical. The Christian hope is that God is going to return to restore the world to right, to bring light into darkness, to create a new creation of shalom and peace, to be present face-to-face with his creatures. It is this hope alone that can bridge the eudaimonia gap between our experience now and our deepest longings. Christian hope for the coming age of flourishing is not escapism but the means by which our otherwise demoralized emotions and our actions are buoyed and energized. As the Christian philosopher David Naugle cleverly observes, biblical happiness is “edenistic,” not “hedonistic”—it is based on God’s creation and re-creation of the world.13

This Christian hope is more than baptized optimism. It is not just the natural inclination of certain personality types. Hope is a virtue to be cultivated. Hope is a virtue of the will that can teach us to embrace both hardships and joys, because it is more than a mere emotion. Even in the midst of the darkest trials, Christians can still have hope. Mysteriously, it is in the darkest times that hope shines the brightest. This was the experience of the ancient prophets, the apostles, and innumerable believers down through history.

Among today’s many psychological therapeutic techniques, one that is particularly promising is called positive psychology. Positive psychology emphasizes habits that people can develop to live more flourishing lives. Several of the theorists within positive psychology have realized that this requires more than just techniques; it also requires a vision for a better future. In short, these secular psychologists realize that for people to flourish, they need hope.

As a result, one subbranch of positive psychology is called hope therapy. Hope, according to psychologist C. Richard Snyder, consists of two main components—the ability to plan pathways to our desired goals and the motivation and ability to use these pathways.14 Therapists have found that people without this kind of hope rarely get better or learn to find balanced lives worth living. Humans can’t survive without some kind of hope.

Roberto Benigni’s character Guido in Life Is Beautiful knew this when he and his son were taken to a concentration camp. At great risk to his life, Guido playfully acted like the camp they were in was actually an elaborate game where the winning team won their own tank at the end. This kept the innocent young Giosué from losing hope—a hope that kept him alive until he was reunited with his mother when the camp was liberated.

But today hope is hard to find, especially when the nihilistic air we breathe is regularly pumped in by high-powered fans of skepticism and apathy. Additionally, even if we learn techniques of short-term goal setting, these will not be enough to sustain us through our complex lives, especially when we experience great suffering and tragedy. A friend of mine is the corporate chaplain for a large regional chain of fast-food restaurants, and he reports that not a day goes by when some employee—from fry-makers to upper management—breaks down in hopelessness because of some personal crisis. This is despite living in the most prosperous country in the world. Even advanced “hope therapy” is insufficient to satisfy the human soul’s need for transcendence, for something that goes beyond the grave and this fallen world as we know it.

The English theoretical physicist and Anglican priest Sir John Polkinghorne observes that we need some kind of “moral cosmology” or else we won’t have the emotional capital for the costly demands of caring for an aging parent or handicapped child. Hope in a real future—an embodied life after death—alone “is the foundation of a moral view that supports and enables the costly demands of fidelity and duty.”15 This is because “hope can sustain the acceptance of such limitation by delivering us from the tyranny of the present, the feeling of need to grab as much as we can before all opportunity passes away forever. We are enabled to live our lives not in the spirit of carpe diem but sub specie aeternitatis (in the light of eternity).”16

Most of the world today does not have this kind of future hope. But the Christian philosophy emphasizes precisely this—an honest assessment of the brokenness of life that is always oriented toward a sure hope for God’s restoration of true flourishing to the world. This is the Good Life according to the Christian philosophy.

We began our discussion by looking at the walls of the ancient church of Dura-Europos. As we discovered, Christians used to think of Jesus as the Great Philosopher, but somehow this got lost. I suggested that the loss of Christianity as a whole-life philosophy has saddled us with four problems:

- Our Christian faith is often disconnected from other aspects of our human lives. Christianity has become merely a religion rather than a philosophy of life.

- We naturally look to other sources—alternative gurus—to give us the wisdom needed to live flourishing lives, to find the Good Life.

- We have stopped asking a set of big questions that Holy Scripture is seeking to answer—questions about how the world really works and how to live in it.

- We have limited our witness to the world.

On the greatest of the philosophical questions—how to live a whole, meaningful, and flourishing life—modern Christianity clearly suffers from these four problems. Even though Jesus said that he is “the way and the truth and the life” (John 14:6) and that he has come to give us “life to the full” (John 10:10), the experience of most Christians today is that our faith is religious but not philosophical.

Here’s a quick test of that. In the two verses that I just quoted from the Gospel of John, what do you think “life” refers to? If your answer is “salvation” or “heaven” or something comparable, then you’ve just proven my point.

Herein lies the nuanced complication. Those future, heavenly-salvation glosses for “life” are not wrong. They’re just incomplete. That vertical and religious interpretation of “life” is part of the story but not the whole. It’s the conclusion to the book but it’s not the whole narrative.

This is why the fastest-growing religion in the world is a dark perversion of Christianity—what is called the health-and-wealth gospel. These pyramid-scheme false teachers are half right, and that’s precisely why they are so effective and so dangerous. They are perceiving, affirming, and providing an answer to the great human question, How do I find a whole, meaningful, and flourishing life now? The half of their ministry that is correct is the recognition that Christianity is indeed speaking to this great question. But the dark, perverted, and ultimately deadly half of their teaching is a failure to recognize that a flourishing life, according to Jesus, includes suffering, disappointment, and loss.

The Christian musician Sara Groves wrote the poignant song “This House” about returning to her childhood home as her parents prepared to sell the house.17 As she reflects on the good and the brokenness of her upbringing, she summarizes it with four terse and effective words—sad, fruitful, broken, true. What a beautiful description of the flourishing reality of the Christian philosophy! True happiness is found in the way of Jesus, and that flourishing life is a complex cocktail that must be drunk in its fullness to feel its effect—sad, fruitful, broken, true.

The reality is that Jesus means it when he says that he has come to bring people abundant life. This includes life now, not just an ethereal future. That flourishing life begins the moment anyone becomes a part of Jesus through faith and hope in him. But our happiness is not complete, and life is mysteriously found in the midst of pain and loss, not in everything getting better and better. Life and happiness are found, not by searching out the perfect Instagram photo that we can tag with #blessed, but in learning to embrace the fullness of life’s emotions and circumstances—dark and bright—through the virtue of hope.

When we return to Holy Scripture, looking to Jesus as the faithful guru of true happiness, we find the biblical answers to be sophisticated, profound, and life-transforming wisdom. When we, as the church, look to Jesus as our Lord, Savior, King, Priest, and Philosopher, we come to know what it means to be a Christian. We learn what it means to take on our role as ministers of the good news. We will be salt and light whose well-lived lives glorify God and draw people to him (Matt. 5:13–16) as we “shine among them like stars in the sky as [we] hold firmly to the word of [the Good] Life” (Phil. 2:15–16).