ACCOUNTING FOR PEARL HARBOR’S JAPANESE MIDGET SUBS

DURING THE NIGHT OF DECEMBER 6, 1941, seven to fifteen miles off the southern side of the island of Oahu, Territory of Hawaii, five midget submarines were launched from specially modified I-boat fleet submarines. The midget submarines were tasked with attacking the American fleet inside Pearl Harbor during the air raid planned for the next morning. During and after the air raid, the mother submarines were to sink any American ships that attempted to sortie from the harbor in pursuit of the Japanese carrier fleet. All of the midget submarines’ two-man crews were prepared to give their lives in service to Japan’s emperor.

The mother submarines sent to Pearl Harbor were I-16 (commanded by Lt. Cmdr. Kaoryu Yamada), I-18 (Cmdr. Kiyonori Ōtani), I-20 (Lt. Cmdr. Takashi Yamada), I-22 (Cmdr. Kiyotake Ageta), and I-24 (Cmdr. Hiroshi Hanabusa). These fleet submarines were modern, most launched between 1940 and 1941, and were capable of long-range missions, able to cruise up to fourteen thousand nautical miles at six knots. On the surface, the submarines could make a maximum speed of 23.5 knots, or 8 knots submerged.

Each Kō-hyōteki kō-gata, or “Type A” midget sub, was referred to by the mother submarine’s number and the term tou. The Pearl Harbor attack midget submarines were manned as follows: I-16tou, crewed by Lt. Cmdr. Masaji Yokoyama and Warrant Officer Sadamu Uyeda; I-18tou, Lt. Cmdr. Shigemi Furuno and Sub-Lt. Shigenori Yokoyama; I-20tou, Lt. Akira Hirō and Warrant Officer Yoshio Katayama; I-22tou, Cmdr. Naoji Iwasa and Sub-Lt. Naokichi Sasaki; and I-24tou, Lt. Cmdr. Kazuo Sakamaki and Warrant Officer Kiyoshi Inagaki. The mother subs were 358.5 feet in length and had a 30-foot beam, carrying the 78.5-foot-long midget submarines on deck aft of the conning tower. To launch a midget sub, the mother sub surfaced to enable the two-man crew to board, check systems, and prepare for the mission. A third midget-submarine crewman, essentially the tou’s crew chief, maintained the mini sub’s systems, helped with the launch, and maintained radio communications after launch. Submerging again, the mother submarine would cruise to the departure location, launch its midget submarine, and then patrol while the mini sub conducted its mission. If successful, the two submarines would rendezvous and leave the area. If necessary, the midget submarine’s crew would abandon their craft and escape onboard the mother sub.

The Japanese midget submarine crews posed for a group photo just prior to departing for Hawaiian waters and their mission to attack Pearl Harbor. From left, I-20tou’s crew of Akira Hirō (seated) and Yoshio Katayama (standing); I-16tou’s Masaharu Yokoyama (seated, second from left) and Sadamu Kamita (standing, second from left); I-22tou’s Naoji Iwasa (seated, center) and Naokichi Sasaki (standing, center); I-18tou’s Shigemi Furuno (seated, second from right) and Shigenori Yokoyama (standing, second from right); and I-24tou’s Kazuo Sakamaki (seated, right) and Kiyoshi Inagaki (standing, right). Burl Burlingame Collection via Parks Stephenson

TYPE A-CLASS MIDGET SUBMARINE

Length |

78.5 feet |

Beam |

6 feet |

Draft |

10 feet |

Displacement |

46 tons |

Propulsion |

600-horsepower electric motors driving counter-rotating propellers |

Speed |

23 knots surfaced, 19 knots submerged |

Crew |

2 |

MIDGET SUBMARINES IN ACTION

In the quiet, early-morning hours of December 7, 1941—at 3:42 a.m., to be precise—Ensign R. C. McCloy aboard US Navy minesweeper Condor (AMc-14) spotted something that appeared out of place. Near the entrance buoys to Pearl Harbor, there was a periscope in an area where US submarines were prohibited from traveling submerged. Around 3:55 a.m., Condor reported its sighting to the destroyer Ward (DD-139) by signal light. Ward pursued the contact but after an hour and a half was unable to locate it. Ward requested the sighting information from Condor again and renewed the search.

By 6:00 a.m., Ward had broken off the search and resumed its regular patrol pattern off the entrance to Pearl Harbor. Lieutenant William W. Outerbridge, skipper of Ward, understood the significance of a Japanese submarine lurking off the harbor’s entrance, but he did not report the phantom sighting to higher command at Pearl Harbor’s Fourteenth Naval District.

Thirty minutes later, the general stores issue ship Antares (AKS-3) arrived off Pearl Harbor with a barge in tow. Lying to near the harbor entrance awaiting a pilot, an object resembling a small submarine was sighted 1,500 yards off Antares’s starboard side. Ward was once again called in to investigate, and at 6:33 a.m. a Navy PBY Catalina patrol bomber from squadron VP-14 marked the sub’s location with smoke bombs. The destroyer ran down the track and began shelling the midget submarine (now believed to be I-20tou).

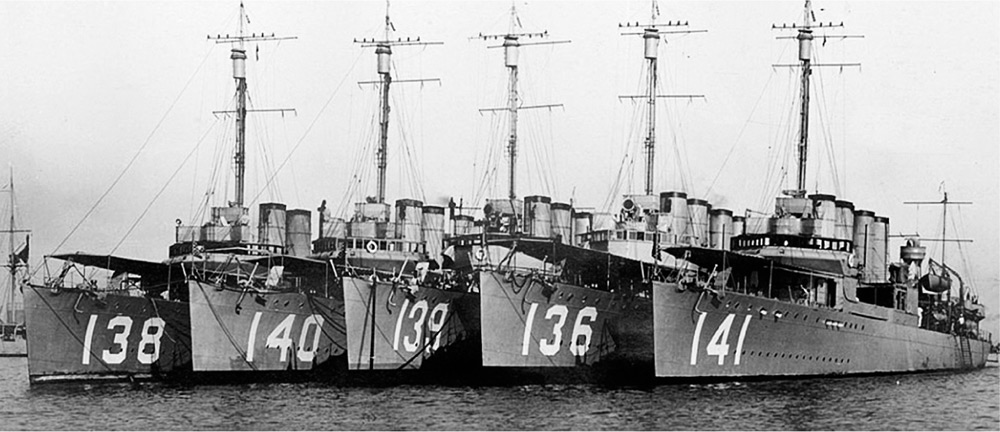

Ward (DD-139) was a World War I–era, 1,247-ton Wickes-class destroyer built at the Mare Island Navy Yard in Vallejo, California. The “four-piper,” so named for its four funnels, was launched on June 1, 1918, and is seen here moored in the San Diego, California, harbor on August 14, 1920. Naval Historical Center

MIDGET SUB CREWS

Commander Crew |

I-24tou | Lt. Cmdr. Kazuo Sakamaki |

I-24tou | W.O. Kiyoshi Inagaki |

I-22tou | Cmdr. Naoji Iwasa |

I-22tou | Sub. Lt. Naokichi Sasaki |

I-20tou | Lt. Akira Hirō |

I-20tou | W.O. Yoshio Katayama |

I-18tou | Lt. Cmdr. Shigemi Furuno |

I-18tou | Sub. Lt. Shigenori Yokoyama |

I-16tou | Lt. Cmdr. Masaji Yokoyama |

I-16tou | W.O. Sadamu Uyeda |

Lt. Cmdr. = Lt. Commander W.O. = Warrant Officer |

Ward’s No. 1 and No. 3 cannon opened fire on the midget submarine. The former’s shot was high, sailing over the conning tower of the Japanese sub. The shot from the No. 3’s four-inch/50-caliber (4"/50) gun, manned by Naval Reservists from Saint Paul, Minnesota, was fired from 560 yards and hit the sub above the waterline near the hull and conning tower joint.

The gun crew from Ward credited with firing the first shot on the morning of December 7, 1941, stands by the 4-inch/50-caliber gun amidships on the destroyer’s starboard side. From left, Boatswain’s Mate 2nd Class R. H. Knapp; Seamen 1st Class C. W. Fenton, R. B. Nolde, A. A. De Demagall, D.W. Gruening, and H. P. Flanagan; Gunner’s Mate 3rd Class E. J. Bakret; and Coxswain K. C. J. Lasch. Naval Historical Center

Mortally wounded by cannon fire, the submarine passed under Ward, which then dropped a pattern of depth charges that sealed the fate of the Japanese midget sub and its two-man crew.

At 6:51 a.m., Lieutenant Outerbridge reported to the Fourteenth Naval District: “We have dropped depth charges upon subs operating the defensive sea area.” Apparently feeling this was not direct enough, he transmitted again two minutes later: “We have attacked, fired upon, and dropped depth charges upon submarine operating in defensive sea area.”

Destroyer Ward had drawn the first blood of World War II, more than one hour before the air raid on Pearl Harbor began, but the significance of the morning’s actions would not be known until later in the day.

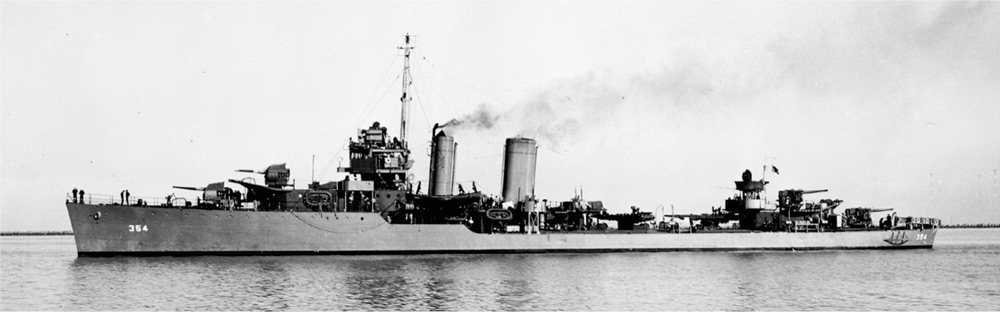

As the attack raged in the skies above Pearl Harbor, I-22tou came under fire at 8:37 a.m. from Curtiss and Tangier. Both ships engaged the midget sub in the channel on the northwestern side of Ford Island. Monaghan (DD-354) ran down the contact, and as the sub flooded its tanks to submerge, the destroyer attempted to ram it. Two depth charges were dropped by the destroyer, and the sub was never heard from again.

Twenty minutes after the air raid ended, the light cruiser St. Louis (CL-49) sortied from the harbor. Near the entrance, her crew spotted two torpedo wakes. St. Louis changed course, and both torpedoes exploded on a reef near shore. At about that moment, the midget sub, now lighter without the weight of the two torpedoes, broke the surface. The cruiser’s gunners opened fire and reported striking the sub, which they claimed sank immediately.

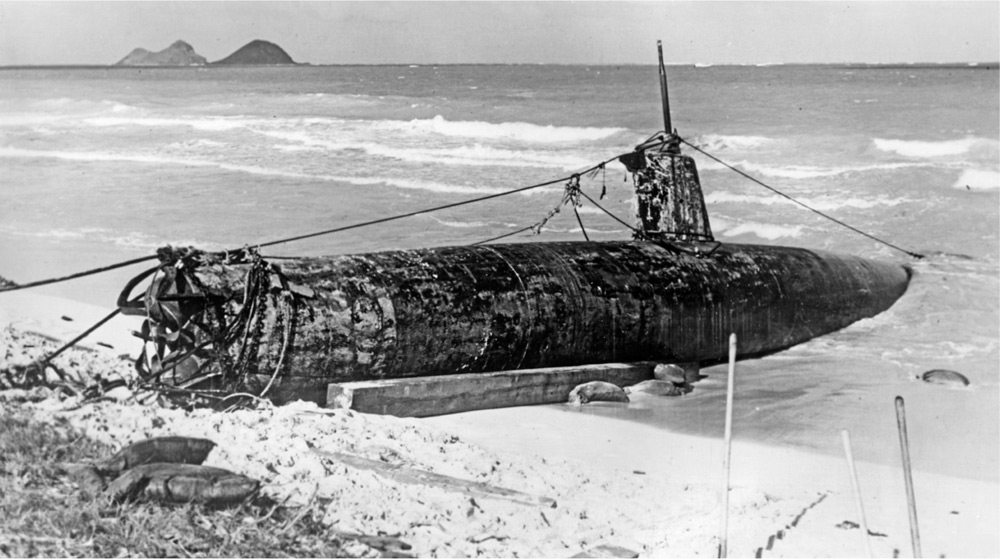

Sakamaki’s I-24tou on the beach at Bellows Field the day after the attack. The midget submarine became stuck in the reef off the beach, but aerial attacks on the sub freed it from the coral, enabling it to float toward shore. It was pulled out of the water and secured using cables. In the following days, the sub was hauled out of the water, dismantled, and trucked to the naval base at Pearl Harbor for a complete inspection. US Navy

PEARL HARBOR MIDGET SUBS

Mother Sub | I-24 |

Mini Sub | I-24 tou |

Fate | Ran aground |

Sinking Location | Bellows Field, Oahu |

Discovery | 8 Dec 41 |

Disposition | National Museum of the Pacific War, Fredericksburg, Texas |

Mother Sub | I-22 |

Mini Sub | I-22 tou |

Fate | USS Monaghan (DD-354) |

Sinking Location | Pearl Harbor |

Discovery | 21 Dec 41 |

Disposition | Buried in pier, Pearl Harbor, Hawaii |

Mother Sub | I-20 |

Mini Sub | I-20 tou |

Fate | USS Ward (DD-139) |

Sinking Location | 1,200 feet down, 3-4 miles off Pearl Harbor |

Discovery | 28 Aug 02 |

Disposition | In situ |

Mother Sub | I-18 |

Mini Sub | I-18 tou |

Fate | Depth charge, attacker unknown |

Sinking Location | Keehi Lagoon, Honolulu |

Discovery | 13 Jun 60 |

Disposition | Imperial Japanese Naval Academy, Etajima, Hiroshima |

Mother Sub | I-16 |

Mini Sub | I-16 tou |

Fate | Scuttled |

Sinking Location | Naval Defense Sea Area, outside Pearl Harbor |

Discovery | 2000 |

Disposition | In situ, discovered in 2000, confirmed in 2009 |

I-24’s midget sub, commanded by Ensign Kazuo Sakamaki, began to have gyrocompass troubles and was unable to enter Pearl Harbor—no matter how many times Sakamaki tried. He eventually ran down the batteries’ charge and was stopped dead in the water. He drifted most of December 7 and eventually ran aground on the opposite side of the island, near Bellows Field, the following morning. Though his crewmen drowned, Sakamaki swam to shore and was captured, becoming America’s first prisoner of war of World War II.

ACCOUNTING FOR THE MIDGET SUBMARINES

In the years following the end of the conflict, historians tried to track the disposition of each of the midget submarines involved in the Pearl Harbor attack. The actions of some subs were known, while the sea held the secrets of others. The fourth and fifth submarines eluded historians for decades, and the final resting places of others raised more questions than they answered.

I-24tou was disassembled and studied at Pearl Harbor, examiners writing an in-depth report of the sub, its components, and its capabilities. It was subsequently shipped stateside, mounted to a low-boy trailer, and hauled around the country on a war bond tour. Eventually, I-24tou arrived at the National Museum of the Pacific War in Fredericksburg, Texas, hometown of Fleet Adm. Chester W. Nimitz, and placed on display.

I-22tou, which was sunk by the destroyer Monaghan inside Pearl Harbor, was raised on December 21, 1941. It was visually evident once the vessel was dockside that it had suffered greatly from Monaghan’s depth charges; the shock waves reverberating on the shallow harbor bottom had intensified damage done to the submarine’s hull. The bodies of Cmdr. Naoji Iwasa and Sub-Lt. Naokichi Sasaki were kept inside the submarine. Days after being recovered, I-22tou was used as fill in the expansion of the submarine base inside Pearl Harbor. Today, the sub is most likely buried underneath a parking lot.

At Bellows Field, a stone cairn and bronze plaque commemorate the midget submarine’s capture and the fate of its crew. Karen B. Haack

Destroyer Monaghan (DD-354) rammed and sunk I-22tou. As the destroyer passed over the midget sub, it dropped a series of depth charges. The midget submarine was raised on December 21, 1941, and it was clearly evident the depth charges had hit their mark. Vallejo Naval and Historical Museum

The midget sub sunk by destroyer Monaghan became fill when the Pearl Harbor submarine base was expanded. Above the pit and to the rear is I-24tou undergoing inspection and reassembly. US Navy

Fifteen years after the Japanese surrender, in June 1960, I-18tou was discovered in seventy-five feet of water in Honolulu’s Keehi Lagoon—just east of the mouth of the entrance channel to Pearl Harbor. The sub was missing its torpedoes, its hatches were unlocked from the inside, and the remains of the crew were nowhere to be found. The midget submarine was raised that summer, returned to Japan, and restored. It’s now displayed at the Imperial Japanese Naval Academy at Etajima Island in Hiroshima Bay.

With the crewmen missing from I-18tou, many have wondered if they abandoned the submarine, swam to shore, and either blended in with the local population during the post–air raid chaos or met accomplices waiting to assist them to a safe house. Were they then to rendezvous with a Japanese submarine to be returned to the home islands? It should be noted that the midget submarine crews wore the same uniforms as the Japanese aircrews—was this an attempt to keep the midget-submarine operation secret, even if one or more of the crews were captured?

With I-24tou aground at Bellows Field, I-22tou sunk by destroyer Monaghan, and I-18tou at the bottom of Keehi Lagoon, that left I-16tou and I-20tou still unaccounted for. The latter is the midget submarine claimed to have been sunk by Ward’s crew. The sub obviously was indeed sunk, since it was never heard from again, but there were many detractors who said that the shot from Ward would have been impossible to make—a claim bolstered by how small a target the approximately five-foot-long conning tower of a Japanese midget submarine would make. Unable to find I-20tou’s final resting place for decades, many of Ward’s crew members passed away before the wreck was found and before they were given due credit for an incredible shot.

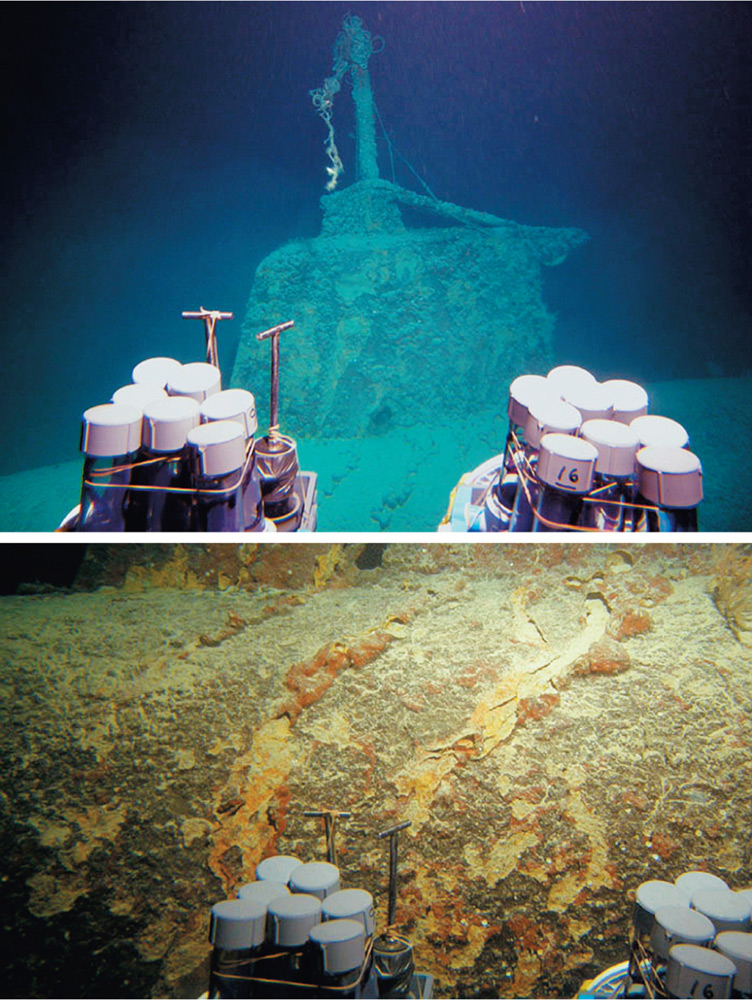

More than sixty years after she was sent to the bottom, on August 28, 2002, the deep diving submersibles Pisces IV and Pisces V, operated by the Hawaii Undersea Research Laboratory (HURL) located at the University of Hawaii’s School of Ocean and Earth Sciences and Technology on Oahu, found Ward’s midget submarine. I-20tou was resting at a depth of 1,200 feet, three to four miles off the mouth of Pearl Harbor. It was clearly evident that this midget submarine had fallen prey to Ward’s gunners due to the distinct hole at the center of the base of the conning tower—right where the veterans said it would be. A better shot could not have been made. Vindication.

During a wartime overhaul, the Navy removed Ward’s No. 3 cannon, credited with sinking I-20tou. In 1958, it was presented to the state of Minnesota in honor of the contributions of its Naval Reserve, whose members manned the gun and made that fateful shot. The cannon was placed on the grounds of the state capitol for all to see.

Ward’s gun crew had claimed that they put a round right through the Japanese midget submarine’s conning tower; a claim many doubted. After sixty-one years, on August 28, 2002, the research submarines Pisces IV and Pisces V from the University of Hawaii’s School of Ocean and Earth Science and Technology’s Hawaii Undersea Research Laboratory (HURL) located the midget submarine five miles off the mouth of Pearl Harbor at a depth of 1,200 feet. The shell’s hole can be seen at the base of the conning tower. HURL

I-16TOU: FATE UNKNOWN

For sixty-eight years, the fate of I-16tou was unknown. Through the years, HURL’s operations director and senior pilot, Terry Kerby, and his team hunted for the both I-20tou and the unaccounted-for I-16tou, the fifth Pearl Harbor midget submarine. Said Kerby:

In 1992, we began using our pre-science-dive-season test dives in an attempt to locate the Ward’s midget submarine. This came about from a meeting I had in 1991 with Dan Lenihan, then director of the National Park Service’s Submerged Cultural Resources Unit [today known as the Submerged Resources Unit]. None of the federal agencies, the Naval Historical Center, National Park Service, or National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration’s National Marine Sanctuaries program could afford to pay for submersibles to wander around in the dark looking for historic wreck sites.

We could only use our first shallow test dive for these searches, and we would only get one dive a year [at most]. On top of that, we would not be able to do it every year. I did the first dive into the defensive sea area to start our search efforts in 1992, and located the tail section of what turned out to be the fifth midget submarine. We could see that it had been disassembled, rigged, and dumped, and assumed it was a war prize that was brought back to Pearl Harbor from the island-hopping campaign.

Eight seasons later, in 2000, we found the midsection, followed by the bow section in 2001, and we finally located the Ward’s midget sub in 2002. After the discovery, NOAA applauded our practice in using test dives to try to support other NOAA science missions and that encouraged us to make it an ongoing effort.

Parks Stephenson and Ward crewman Will Lehner with one of HURL’s Pisces research submarines. Lehner was a fireman, second class, on board Ward during the December 7, 1941, sinking of I-20tou. Courtesy Parks Stephenson

During each diving season’s explorations, HURL’s Steve Price accumulated a list of what historical artifacts were on the bottom in the waters off of South Oahu and their precise locations. From this, Price built a database of artifacts, which in subsequent years has enabled a number of historic maritime discoveries.

After the discovery of I-20tou, the HURL team noticed it was a carbon copy of the three-piece midget sub. Steve Price researched Japanese midget-submarine configurations and discovered that the figure-eight torpedo guard arrangement was only used on the Pearl Harbor attack subs. Kerby elaborated:

With Price’s research, we then confirmed that we had, indeed, found the fifth midget submarine. From looking at the three sections, one can see that the sub had blown apart aft of the conning tower and we knew from studying the Sydney Harbor midget sub that it was most likely from a scuttling charge. It had later been disassembled, rigged for disposal, and dumped in the defensive sea area.

We felt confident enough that we had located the fifth midget sub that we went public with the discovery on December 5, 2006, when HURL chief biologist Chris Kelley gave a talk in Session 19 of the Pearl Harbor symposium “A Nation Remembers,” where he presented the Kerby-Price theory on the discovery of the fifth and final midget submarine.

The HURL team had found I-16tou outside of Pearl Harbor, and the evidence lying on the sea floor around the sub’s parts gave them a good idea where it had initially sunk. After having located all of its components, the team then returned to the task at hand: undersea science missions.

The discovery of Ward’s midget sub generated a number of documentaries, one of which one was a History Channel production with diver John Chatterton. After it was completed, Chatterton expressed interest in working with HURL on future discoveries, and the information Kerby and his team developed on the fifth midget sub was forwarded to him. Chatterton, in turn, provided the HURL information to the Lone Wolf Documentary Group, which was working on a midget-sub production with Parks Stephenson, a graduate of the US Naval Academy (class of 1979), former submariner, and flight officer in E-2C Hawkeye airborne early-warning aircraft. Using the HURL data, Stephenson and Lone Wolf produced a PBS NOVA program titled Killer Subs in Pearl Harbor, which aired in 2010. The documentary team validated HURL’s discovery by adding one final confirmation to the story of the fifth midget sub.

Having secured funding from the production company, Stephenson and the documentary team left for Japan to interview surviving submarine veterans. As Stephenson explained, one of the veterans had an interesting story to tell:

Each of the midget sub-crews was a three-man crew. Two stayed in the sub and the third was, basically, the guy who took care of the sub while it was transported to the attack area on the back of the mother sub. Then, he saw the sub off, and he was the one to receive battle reports from the subs after they completed their mission. This gentleman, who was the only survivor of this cruise, said that almost toward midnight [on] the night after the attack, twelve hours after the last attacking Japanese aircraft had departed Oahu, he had received the pre-arranged signal from I-16tou reading mission success.

Each of those subs had a discrete frequency, so he could only have heard a broadcast from his sub. This crewman, waiting aboard the I-16 mother sub, had been instructed to listen on a certain frequency, and it was something like ten forty-five or eleven p.m., the night of December 7, [that] he received the Tora call. The submariners used the same codes as the aviators; we know this because there was a chart recovered from I-24tou that beached itself on the far side of the island. This chart gave the mission codes, and Tora was mission success.

The documentary crew’s request to film the midget sub’s wreckage was added to a NOAA-funded dive series with NOVA and Japanese TV network NHK picking up the cost of extending the mission by two days to include a visit to the fifth midget submarine. For the expedition, Stephenson brought a survivor from Ward and retired Japanese admiral Ueda Kazuo (JMSDF), who had been a midget submariner late in the war. Admiral Ueda descended to the wreck in Pisces IV with Maximillian “Max” Cremer piloting the research submarine, and it was he who gave the final validation of the HURL discovery.

“Diving down onto the wreck itself, the admiral concurred with the assessment that the details of the wreck were consistent with a Pearl Harbor attack midget sub and only to a Pearl Harbor sub,” said Stephenson. “He brought mementos from the families of the two crewmen and offered them up in the submersible at the site. Kerby, who was piloting Pisces V, was able to get a scoop of sand from underneath the wreck. That was presented to the admiral, who took it back to Japan and presented it to the families. The Japanese were the final validation that we needed for the wreck, but [even] before they gave their validation, everyone involved was pretty certain that it was the missing sub based on the physical details of the wreck [in particular the figure-eight torpedo guard at the bow].”

Collaboration between Terry Kerby and Parks Stephenson put together the final fate of the fifth Japanese midget submarine from the Pearl Harbor attack.

MAKING THE DIVE

Stephenson described the exploration of I-16tou:

In HURL’s Pisces submersibles, we went down to about fifteen hundred feet. That was the depth of the Defensive Sea Area where the sub wreck was. The submersible takes its own atmosphere down with it, so you climb in, shut the hatch, and then descend. Carbon dioxide that is exhaled is scrubbed onboard and the atmosphere is no different [from] a submarine, really. It’s just all a lot more cramped.

What we saw when we got down there was fascinating because the Defensive Sea Area outside of Pearl Harbor was a dumping ground for decades. You can see all kinds of stuff out there. Mostly war materiel, but you’ll see cars and trucks, boats and planes, and ammunition. Live ammunition just dumped into the water. I don’t know how many sixteen-inch shells we went over, just lying on the bottom. Rounds and rounds of ammunition.

As we got near the submarine wreck, what really caught my eye were these LVT amphibious track vehicle wrecks. They would later play into the theory on what happened to the midget sub and the circumstances under which it was found.

We got to the wreck of the midget submarine and confirmed that it was in three pieces, which was unusual. The midsection was blown apart. It looked like an internal explosion because the metal was bent outward and the location corresponded to the position of the scuttling charge that was known to be aboard the subs.

The midget subs were constructed in three sections. There are large seams before the conning tower and aft of the conning tower where the bow, center, and stern sections are bolted together. They had been separated, but more than just separated, the bolts had all been cut. Because we found evidence of bolts that were still concreted into their holes, it was evident that the Navy didn’t just unbolt it and disassemble the sub. It had been underwater for a while and flooded, allowing the bolts inside holding the extensions together to become concreted in place.

Then, against that evidence were two empty torpedo tubes, which show no evidence of concretion, at least not with a torpedo in its tube. That would later lead us, after we had a forensic analyst who is [an] expert in shipwrecks and corrosion, assess that the torpedoes had left the tubes before the sub had been sunk.

The fact that the sub was broken up into three pieces and the salvage cable that was used to dump it over the side was still run through each of the pieces was another clue. Navy salvors actually ran the cable through the open end of one section and then punched a hole in the hull to help lift the sub’s sections over the side.

The juxtaposition of the midget sub and the LVT-2s hinted that maybe the US Navy found the sub after the West Loch explosion in 1944. During the Pearl Harbor attack, there were some indicators of sub activity heading toward the West Loch area from eyewitnesses, and then finding these LVT-2s drew it all together. We have no documentation, of any kind, mentioning the recovery of this sub, the examination of this sub, or the disposition of the sub. The US Navy obviously raised it and disposed of it, but there’s no documentation for that.

I-16TOU AND THE WEST LOCH DISASTER

Kept secret for more than fifteen years, the West Loch Disaster occurred in May 1944 and was not made public until 1960. LSTs (Landing Ship, Tank) were being loaded in Pearl Harbor’s West Loch in preparation for Operation Forager, the invasion of the Mariana and Palau Islands.

In the May 21 incident, twenty-nine LSTs were moored in the West Loch and were being loaded with ammunition and supplies for the 2nd and 4th Marine Divisions’ amphibious assault of the islands. At 3:08 p.m., LST-353 exploded and started a chain reaction, causing nearby ships to add to the conflagration. LST-39, LST-43, LST-69, LST-179, and LST-480 were sunk, and four additional LSTs were heavily damaged but later returned to service. More than fifteen LVTs and a number of 155-millimeter howitzers were also destroyed.

The final theory on the fifth midget submarine’s final voyage is that I-16tou made a successful attack during the Pearl Harbor raid, then navigated itself into West Loch. With the harbor entrance sealed off by a now-vigilant American military, I-16tou’s crew sent the successful attack code and either abandoned their craft or activated the scuttling charge and perished in the resulting explosion. The midget submarine sank to the bottom of West Loch, only to be discovered by the US Navy when clearing debris—sunken LSTs and LVTs—from the area after the May 1944 disaster. The sub was hauled aboard a barge, sectioned into three pieces at the production breaks, then hauled out to sea and dumped with the remains of the West Loch incident. What remains unanswered is what happened to the midget submarine’s crew.

MIDGET SUBMARINES IN SITU

Today, I-20tou and the components of I-16tou are jointly managed by NOAA’s National Marine Sanctuary Program, HURL, and the National Park Service with assistance from the Naval History and Heritage Command.

Having the lead role in managing the two midget subs, NOAA has funded dives to the sites using the Pisces submersibles, the most recent in 2013. After sitting in corrosive saltwater for more than seventy years, both subs are beginning to deteriorate, and changes in their condition are being meticulously documented. The torpedo guard on Ward’s midget sub has deteriorated and fallen into the sand while the aft section is separating at the production joint, and the tail has separated and fallen to the sea floor.

The fifth midget sub is losing its battle with the elements as well. The hull is failing, and the conning tower will soon topple from the hull. Other small artifacts have been cleared from the conning tower’s shadow and moved to safer locations so they will not be eventually crushed. For example, the aft running light that had deteriorated and fallen to the sand was picked up, placed in a bucket and tagged with the artifact’s identification, filled with clean sand, and moved to a safer location on the wreck.

As the months go by, NOAA’s Marine Sanctuaries program and the other stewards of the Pearl Harbor midget subs are developing plans for how to manage the wrecks, increasing the public’s awareness of them while respecting that one or both are war graves.

Five months after the midget submarine attack on Pearl Harbor, the city of Sydney, Australia, was targeted by the two-man submersibles. During the night of May 31–June 1, 1942, a trio of Japanese midget subs entered Sydney Harbor. Two were detected and attacked; a third sent torpedoes after the cruiser Chicago but instead sank the Australian depot ship Kuttabul. The midget submarine seen here was recovered from the waters off Guadalcanal and is today displayed at the Submarine Force Museum in Groton, Connecticut. Library of Congress

REFLECTING UPON THE JAPANESE SUBMARINE THREAT

US naval forces in the Hawaiian Islands were constantly training to meet an expected threat: that of a submarine attack. It was theorized at the time that Japanese submarines would lie in wait at the mouth of Pearl Harbor and torpedo a number of ships in the harbor’s entrance channel, thus bottling up the fleet. With the US Navy unable to sortie from the harbor, the Japanese would then invade Oahu.

Taking Oahu would have given the Japanese a staging base for an attack on the military and industrial targets on the West Coast at San Diego, Los Angeles, and San Francisco, California; Portland, Oregon; and Seattle, Washington. The Japanese could also have used Pearl Harbor to block shipping to Australia and other Allied nations, and a full-scale invasion of the US West Coast could have become a possibility as well.

“If one studies the Pearl Harbor battle, it was total success for antisubmarine warfare forces, and a total failure for the Japanese submarine force,” said Parks Stephenson. “The first shot of the attack was by the destroyer Ward, and its target was a submarine. So the first shot, and the first victory, of Pearl Harbor went to the United States during the battle. After the attack, the American destroyers sortied, and they aggressively kept down and neutralized the Japanese fleet submarines that were all positioned outside the harbor. We were ready, but we weren’t ready for the right threats, and that’s what caught us off guard.”