CAUGHT IN THE OPEN

HMS REPULSE AND HMS PRINCE OF WALES

IN AN ATTEMPT TO PREVENT THE JAPANESE from attacking British possessions in Borneo, Malaya, and the territory known as the Straits Settlements—which included Malacca, Penang, and Singapore, among others—the Royal Navy battleship Prince of Wales and battlecruiser Repulse were dispatched to Singapore as a projection of strength.

Known as “Force G” during their deployment from the United Kingdom, Prince of Wales and Repulse were accompanied by destroyers HMS Electra, Encounter, Express, and Jupiter, arriving in Singapore on December 2, 1941. The group was redesignated as “Force Z” upon arrival. The aircraft carrier Indomitable was to rendezvous with the Force Z ships at Singapore, but the carrier ran aground off Jamaica. She was in dry dock at the American naval base at Norfolk, Virginia, and did not make the passage to Malaysia. Thus, the Force Z ships had no sea-based air cover available to protect them.

In the early morning hours of December 8, 1941, Japanese high-altitude bombers attacked the British stronghold at Singapore. Prince of Wales and Repulse responded with antiaircraft fire but did not suffer any damage. Simultaneous to the bombing, twenty-four thousand Japanese troops landed at Kota Bharu, approximately 460 miles north of Singapore.

At 5:10 p.m., local time, Force Z (Prince of Wales, Repulse, and destroyers Electra, Express, Tenedos, and Vampire) sortied from Singapore Harbor to attack the Japanese invasion force. The following afternoon, December 9, the Japanese submarine I-65 detected the British ships and trailed them, reporting their position as they moved north. Having received I-65’s reports, the invasion force’s commander, Vice Adm. Jisaburō Ozawa, turned his now-empty transports back toward port at Cam Ranh Bay in Japanese-occupied French Indochina.

The British force was then located by scout planes from the cruisers Kinu, Kumano, and Yura at approximately 5:30 p.m. Shortly thereafter, destroyer Tenedos, being short on fuel, left Force Z and headed back to Singapore. Darkness fell over the British ships as they pursued the Japanese invasion force. A night attack was launched by Japanese land-based bombers, but they were unable to locate the British ships as stormy weather closed in.

At around 10:00 p.m., a patrolling Japanese seaplane mistook the heavy cruiser Chōkai for Prince of Wales and dropped a flare. As the Japanese naval force turned to the northeast, ships in Force Z spotted the flare as well. Admiral Sir Tom Phillips, commander of Force Z, immediately turned his ships to the southeast. Unable to locate the Japanese ships, Phillips decided to return to Singapore to await further developments.

At 3:40 a.m., Force Z steamed past I-58. The submarine gave chase, firing five torpedoes at the British ships, none of which found their targets. I-58’s position reports were picked up by the 22nd Air Flotilla, which prepared ten aircraft to search for the ships at first light.

During the night, Phillips received word that the Japanese had landed at Kuantan, about 250 miles north of Singapore; he turned his ships and headed in that direction. This had the unintended consequence of throwing off the Japanese search planes, which did not locate the ships of Force Z until 10:15 a.m. One hour later, eight twin-engine Mitsubishi “Nell” (G3M) bombers concentrated their attacks on Repulse. Seven 550-pound bombs missed, but one struck the battlecruiser in the starboard stern deck area.

During her short career, HMS Prince of Wales saw a lot of action. Built at Birkenhead, England, across the River Mersey from Liverpool, she was completed in March 1941. The ship was heavily damaged in the fight to sink the German battleship Bismarck, and after repairs went on to fight the Italians in the Mediterranean. Prince of Wales arrived in Singapore on December 2, 1941. Six days later, Prince of Wales, battlecruiser Repulse, and four destroyers encountered Japanese airpower in the South China Sea. National Archives

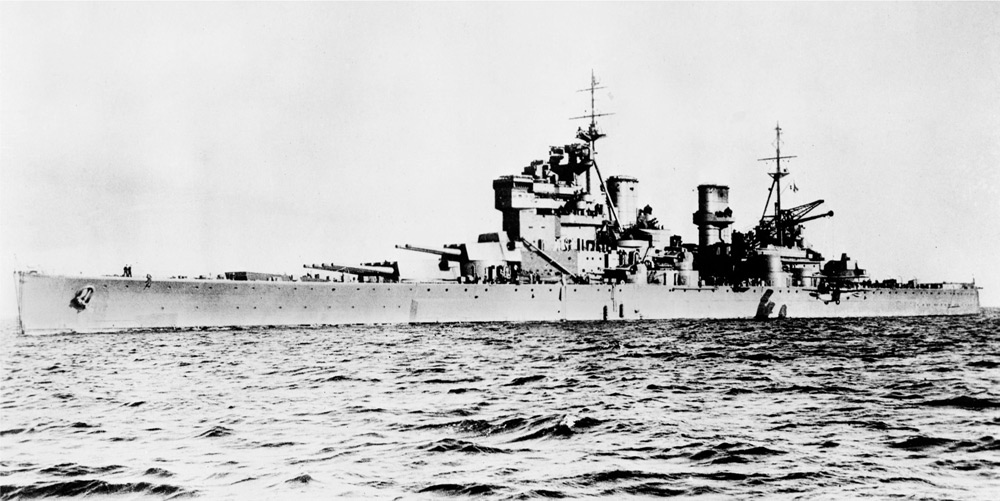

The battlecruiser HMS Repulse joined the British fleet in 1916, undergoing modifications in 1922 and again in 1933. The second modernization lasted three years and saw the ship fitted with improved deck armor and additional antiaircraft batteries. In May 1941, Repulse was part of the squadron that sank the Bismarck. In the fall of 1941, she was sent to protect British interests in the Far East. Naval Historical Center

A Japanese photo from the opening attack on Repulse, bottom of frame, and Prince of Wales. Seven near misses can be seen in the waters around the stern of Repulse, and the dark area covering the starboard stern section is a direct hit. Neither ship had long to live. Naval Historical Center

At 11:45 a.m., two squadrons of Nell bombers fitted with torpedoes came in for the attack. Eight torpedoes were aimed at Prince of Wales and nine sped toward Repulse. All torpedoes, except for one, missed. One torpedo struck Prince of Wales at the junction where the outer propeller shaft exits the lower hull. This threw the propeller out of balance, chewing into the inner port propeller, which caused the prop shaft to break. The outer propeller fell away, and water rushed into the hull through the now out-of-round shaft opening. The in-rushing water caused the battleship to list 11.5° to port, which cut power to her pumps, the secondary armament, and steering. Powered by just her starboard engines, Prince of Wales was able to make fifteen knots, but directionally she was unstable.

While Prince of Wales was dealing with her problems, Repulse came under concentrated torpedo attack. Ten more Japanese torpedoes were aimed at the British battlecruiser, with one finding its mark on the port side. Two more torpedoes hit the ship as well. Repulse was built with a shallow antitorpedo bulge, and the explosion of the torpedo’s warhead pierced directly into the side of the ship. Without the watertight compartmentalization of newer ships, Repulse was unable to stem the flooding. Within six minutes, the ship rolled over and sank.

A low-level photograph of Force Z’s demise taken from a Japanese torpedo-bomber. At far left is Prince of Wales, with Repulse in the background, second from left. In the foreground is a British destroyer. Prince of Wales was heavily damaged in the first wave of torpedo attacks. National Archives

Three more torpedoes found Prince of Wales and one 550-pound bomb struck the deck amidships, exploding below decks. As the battleship continued to list, destroyer Express pulled along her starboard side to aid the crew as they abandoned ship. At 1:18 p.m., Prince of Wales slid under the South China Sea. Both of the Royal Navy’s largest capital ships in the region were gone.

In this photo shot from the bridge of the HMS Express, the destroyer has put its hull next to Prince of Wales to enable the battleship’s crew to jump from one ship to the other. Prince of Wales is listing heavily to port as men can be seen clambering over her side. Author’s collection

SPECIFICATIONS: HMS REPULSE

Length (overall) |

794 feet 1.5 inches |

Beam |

90 feet 1.75 inches |

Draft |

27 feet |

Displacement |

27,200 tons |

Powerplant |

2 steam turbines driven by 42 water boilers |

Top speed |

31.5 knots |

Crew |

968 officers and sailors |

Armament |

6 15-inch guns in 3 dual gun turrets

9 4-inch guns (triple mounts)

8 4-inch guns (dual mounts)

8 20-millimeter cannon

8 21-inch torpedo tubes |

Class |

Renown-class battlecruiser |

Builder |

John Brown & Co., Clydebank, Scotland |

Launched |

January 8, 1916 |

Commissioned |

August 18, 1916 |

Sunk |

December 10, 1941 |

SPECIFICATIONS: HMS PRINCE OF WALES

Length (overall) |

745 feet 1 inch |

Beam |

103 feet 2 inches |

Draft |

34 feet 4 inches |

Displacement |

43,786 tons |

Powerplants |

Geared steam turbines driving 4 propellers |

Horsepower |

100,000 shaft |

Top speed |

28 knots |

Crew |

1,521 officers and sailors |

Armament |

10 14-inch guns

16 5.25-inch guns

32 40-millimeter cannon

80 antiaircraft rocket projectors |

Class |

King George V–class battleship |

Builder |

Cammell Laird and Co., Ltd., Birkenhead, England |

Launched |

May 3, 1939 |

Commissioned |

January 19, 1941 |

Sunk |

December 10, 1941 |

DIVING THE PRINCE OF WALES AND REPULSE WRECKS

Today, the wrecks of Prince of Wales and Repulse lie eight miles apart, approximately 120 miles north of Singapore and fifty miles north of the island of Pulau Tioman, a popular resort diving destination. As a dive site, the scale of Prince of Wales is mind boggling. It’s 750 feet long, and she was a quantum leap ahead of her contemporaries—more than two hundred feet longer than other World War I battleships.

Rod Macdonald, diver and author of Force Z Shipwrecks of the South China Sea, has made a number of descents to both Prince of Wales and Repulse. Macdonald’s first trip to the Force Z shipwrecks was in 2001 at the invitation of the British military, serving as a consultant to the service’s divers, who were testing the use of trimix gasses.

Diving the shallowest parts of Prince of Wales can be done on air, but at the ship’s depth of approximately 225 feet, using trimix—a combination of oxygen, helium, and nitrogen—is safer and provides for more bottom time. The wreck of Repulse can be safely dived on air, as it is shallower, with the ship’s starboard rail at 125 feet and the bottom at 180 feet. Although both wrecks can be dived the entire year, the best times are March and April and again in September through November, when the water is a comfortable 86° Fahrenheit and visibility can be more than 120 feet.

“On my first visit, we tied into Prince of Wales for a week of dives,” said Macdonald. “At the wreck, there’s a monsoon current that runs in one direction six months of the year, then it runs the other direction for the other six months. It’s a very steady current at about two knots. We used underwater scooters that moved at two and a half knots, meaning that even in the current we could get around these wrecks quite easily.”

Prince of Wales is lying upside down in 230 feet of water, and the bottom of the hull—the top of the wreck—comes to between 160 and 180 feet of depth. In addition, Prince of Wales sits beam-on to the prevailing current. The current sweeps along the seabed, hits this massive obstruction (the 750-foot-long hull), and stirs up all the sand and sediment. Said Macdonald:

There’s a lot of debris lying around the wreck on the seabed. It’s a clean, white, sandy seabed, and artifacts lie where they fell when the ships sank. Because the current changes direction, there’s not a great pile-up of silt against the hull covering it up—it’s all swept away. It’s very much the battle scene that it was when the ship went down. There’s still a number of Carley floats [life rafts made from a copper tube covered with cork and canvas] recognizable on the bottom.

The water on the way down to the wreck is very clear, with one hundred to two hundred feet of visibility. At the top of the wreck it’s okay as well, but as soon as you go over the side to where the current is hitting the hull, it can be very cloudy and the visibility can drop down to ten to twenty feet. The sediment-filled water can have a milky sort of feel to it.

Most divers will descend to the top of the upturned hull, then drop over the side. It’s a descent of another sixty feet along the sheer side of the battleship’s hull to reach the rail along the main deck. Here, divers start to see all the recognizable features of the battleship—the superstructure and the secondary armament—albeit upside down. On most diving expeditions, the group heads to the most recognizable feature, the main batteries. “What is most impressive is their position,” said Macdonald. “I was scootering along the side of the starboard ship looking for A turret, which is the one with the four big, fourteen-inch main guns. I ducked underneath the overhanging hull, and through the murk I could see a strip of light green one hundred feet in the distance. I realized when I looked around that the whole bow from the forward turret was actually suspended off the seabed by the strength of the armor and the turrets. The whole bow was one hundred to one hundred and fifty feet off the seabed and I was looking across the entire beam of the ship to the port side. It is an amazing sight to see.”

Diving the wreck of Repulse is different. This ship is a battlecruiser, so it’s the same length as Prince of Wales but not as big overall. The wreck is rolled more onto the port side, so it is not completely upside down like Prince of Wales. Her orientation on the bottom enables the monsoon current to run from bow to stern, and this sweeps all of the sediment away. “At Repulse, the underwater visibility is a staggering one hundred to two hundred feet of visibility,” said Macdonald. “She’s a far cleaner, silt-free wreck, and because she’s more on her side you can see an awful lot more of her. The main guns are easy to see. The midship’s conning tower and bridge superstructure and all the side armament are all recognizable and exposed. This wreck is more easily accessible as she’s not quite as deep as Prince of Wales.”

A diver maneuvers around the twin fifteen-inch gun barrels of Repulse’s B turret. The ship rests on her port side in 180 feet of water; her starboard side is only 125 feet below the surface, making this an easy descent for technical divers. Unfortunately, the wreck’s shallow depth also makes Repulse and Prince of Wales a target for metal scrappers, who are, essentially, slicing and dicing the gravesites of more than eight hundred British sailors. The wreck lies approximately 120 miles northeast of Singapore. Guy Wallis, courtesy Rod Macdonald

ILLEGAL SALVAGE ACTIVITY ON THE WRECKS

“There has been a considerable degree of illegal salvage activity going on over the last few years on these wrecks and the war wrecks of other nations in the area,” said Macdonald.

During the battle, a torpedo struck Prince of Wales beside the bracket that holds the three-part propeller shaft that connects the hull to the propeller. Now out of balance, the shaft started vibrating and thrashing around inside the hull, eventually breaking the seventeen-inch shaft made of the best British steel. That propeller fell away to the seabed, and the battleship eventually sank with the three remaining propellers. Macdonald said:

The camera points down the twin fifteen-inch gun barrels of B turret out into the South China Sea. The range finder and rear section of A turret can be seen at right. Unfortunately, the large 15-inch guns were of no use in defending the ship from the high-level and torpedo-bombers of the Imperial Japanese Navy’s 22nd Air Flotilla. Guy Wallis, courtesy Rod Macdonald

Each of these props is absolutely massive, probably fifty tons of phosphor bronze. They were lifted off the wreck [in 2013], and the two remaining props from the Repulse were also taken. Earlier this year, Malaysian authorities caught a salvage barge working Japanese war wrecks off the west coast of Malaysia and impounded it with four million dollars’ worth of scrap metal on board.

We thought that was the end of it, but the problem continues to grow. There was a party of divers at the wreck sites at the end of 2014, and they found a number of explosive charges on the hulls. Unscrupulous divers are setting charges to separate the hull plates so they can be removed and the steel recycled for money. Each of the hulls had explosives wired together with detonation cord in coffee tins strung together. And these things were all over the wreck and they were getting ready to fire.

I think what’s happened is that the salvage vessel that’s working the wrecks had seen the dive boat approaching the site on radar and they left the scene, or had gone just over the horizon to hide. Once the dive vessel left after the dives were complete, as it was cruising away, the divers heard three loud explosions coming from the direction of the wrecks. The salvors had returned and fired the charges. The illegal salvage work is still ongoing; however, this salvage barge has now been seized. British divers are appalled by what has been happening because these are very sensitive British war graves. Hopefully these arrests will see an end to what has been happening—but a significant amount of damage has already been inflicted on these war graves.

To bring the problem closer to home, the damage being done to Prince of Wales and Repulse is equivalent to someone trying to salvage a hallowed American site like the battleship Arizona or strip-mine the Gettysburg battlefield. Do it and you’ll have a fight on your hands.

Unfortunately, Prince of Wales and Repulse lie in international waters, which limits Britain’s rights to protect the wreck sites. Both of the shipwrecks are considered “protected places” under the British Protection of Military Remains Act, but nationals of countries outside the United Kingdom do not have to honor the act.

“The Malaysian authorities are trying to stop this plundering, but the salvage barge comes from China or another nation that does not honor our war dead,” said Macdonald. “It’s somebody who we don’t have positive relations with and all they see is metal that can be converted to money. They’re actually salvaging Japanese and Australian warships as well. It’s absolutely disgusting.”