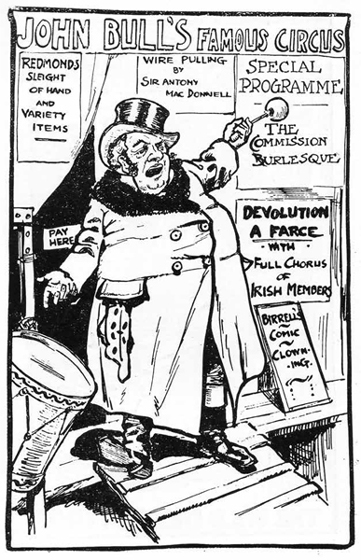

‘John Bull’s Famous Circus’, a cartoon by Robert Lynd for Bulmer Hobson’s short-lived newspaper the Republic, 11 April 1907, indicates the contempt felt by the younger generation for the world of constitutional nationalism.

You see, my parents are not quite like myself. I think I am rather characteristic of a certain section in Ireland. The younger people of Ireland have been thinking in a way that some of the older ones have not.

– Muriel MacSwiney, Testimony to American Commission

on Conditions in Ireland, 9 December 1920

I

The men and women who made the Irish revolution knew that they were different from their parents. The way that the constitutional-nationalist Irish Parliamentary Party lost its grip on Irish opinion reflected a generational shift; the fracture between old and new broke along lines of age as well as of ideology. Older people, such as the Fenian Tom Clarke – who had served his time in British prisons for republican activities before returning to Ireland in 1907 and was fifty-eight years old in 1916 – were recognized as exceptional by their acolytes. ‘To all the young men of the Separatist movement of that time he was a help and an inspiration,’ recalled the passionate young Cork nationalist P. S. O’Hegarty. ‘And he was surely the exception in his own generation, the one shining example.’1 For radical nationalists of O’Hegarty’s age (he was born in 1879), the previous generation had sold the pass to craven constitutionalism, by deciding that the Fenian agenda of achieving separation from Britain through physical force was outmoded, and opting for parliamentary agitation instead. For them the world of secret revolutionary societies, spectacular dynamitard gestures, and doomed risings like the damp-squib Fenian insurrection of 1867, were a thing of the past. O’Hegarty used his ample spare time, during his employment as a British civil servant in the Post Office, to write a great deal of journalism intended to prove that this analysis was wrong.

But the older generation continued to see things differently. A year and a half before the Easter Rising of 1916 the parliamentary nationalist leader John Redmond made a speech at Wexford which described modern Ireland as the Irish Parliamentary Party saw it:

People talk of the wrongs done to Ireland by England in the past. God knows standing on this holy spot it is not likely any of us can ever forget, though God grant we may all forgive, the wrongs done to our fathers a hundred or two hundred years ago. But do let us be a sensible and truthful people. Do let us remember that we today of our generation are a free people (cheers). We have emancipated the farmer; we have housed the agricultural labourer; we have won religious liberty; we have won free education . . . we have laid broad and deep the foundations of national prosperity and finally we have won an Irish parliament and an executive responsible to it (cheers).2

This reflected a number of key reforms won by the Home Rulers through the machinery of the Westminster parliament, culminating in the Home Rule Bill, which gave the projected Irish parliament fairly wide powers of autonomy, while firmly retaining imperial supremacy.3 Nonetheless, Redmond was a figure scornfully regarded by most young radicals, who believed that he and his parliamentary colleagues lived an indolent and corrupted life among the fleshpots of London – a rather unfair image of the existence of the average Irish Parliamentary Party member. More profoundly, to the minds of O’Hegarty and his friends in the advanced-nationalist clubs of Cork, Dublin and London, the constitutional achievements itemized by Redmond were neither relevant nor accurate. It is worth remembering that Redmond’s claims would have chimed with the opinions of the majority in Ireland in 1915; the radicals were still a minority. At the same time, many of the attitudes and beliefs which they embraced so fervently were echoed, if in a diluted and perfunctory form, by the rhetoric of constitutional nationalism. That Fenian pedigree which Tom Clarke represented was often invoked from Irish Parliamentary Party platforms. In the later memories of those who participated in the 1916 Rising, a hereditary Fenian indoctrination would be the predominant feature of their pre-revolutionary conditioning.4 And – without the benefit of hindsight – O’Hegarty’s young friend Terence MacSwiney, writing his diary in 1902, recorded proudly that he was an ‘extremist’.

There is something very ironical in the fact of this term [extremist] being applied by those Irish politicians who are known as ‘constitutional’ if we only examine the matter closely enough. The ‘extremist’ so-called is one who has an ideal and strives to the best of his ability to aid in the realization of that ideal . . . And so the ‘extremist’ keeps the ideal of nationality unsullied and adopts for his watch-word – No Compromise . . . But the Constitutionalist’s idea of our rights is a home parliament under the English flag; and if you attempt to explain to him that this is not the full measure of our rights but that in reality our country should be raised to a position of Sovereign Independence, he will in all probability tell you that you are an ‘extremist’.5

For some ‘extremists’, like MacSwiney, the notion of a righteous war of liberation was a desideratum from early youth; the idea pulses through his personal writings in the early 1900s, supplying a romantic counterpoint to his daily life working as a clerk and studying at night-school. This belief was founded in imbibed ideas of history, from mentors at school as well as at home, which will be discussed later in this book; it was also founded in a fervent and mystical devotion to Catholicism.

But extremism could flourish in other seed-beds too, and the beliefs embraced by MacSwiney were also articulated by radicals from very different backgrounds. Feminism, socialism, anti-imperialism, anti-vivisectionism were among the anti-establishment beliefs appealing to young people in the Edwardian era, in Ireland as in Britain. Several of them also embraced secularism, as O’Hegarty, writing from London in 1904, tried to explain to his old Christian Brothers schoolfellow:

you will be surprised to hear that I am an anti-cleric. I don’t hold that the priests are our natural enemies but I do think strongly that they have acquired the habit and that nothing but strong determined action will break them of it. They ruined every movement – directly or indirectly – since the passing of the Maynooth Grant in 1795 and we have to put them in their places if we are going to do anything. Even today the U[nited] I[rishman] is an ‘atheistic’ paper and daren’t be sold outside the towns. There’s no use shutting our eyes to the fact that the hierarchy are governed indirectly from London through Rome . . . The Catholic Church in Ireland wants reform root and branch quite as much as it did on the Continent prior to the Reformation. We have no true religion in Ireland for our religion is alien not national. Most of the fellows here are anti-cleric to a greater or less degree . . . It is only when a man leaves Ireland that he begins to see straight on some things, this amongst them.6

This echoed the anti-clericalism professed by some Fenians in the 1860s, but it also suggests the impatience of young radicals with the power of Catholicism in Irish life by the early twentieth century. While removal to London could accentuate this reaction, other radicals, especially from Protestant backgrounds, needed no encouragement to see the Catholic Church as one of the main obstacles to liberation – along with the Irish Parliamentary Party. The two were often jointly identified through the Ancient Order of Hibernians, the Catholic political and social association founded in Ulster, led by the Belfast politician Joe Devlin and routinely denounced by ‘extremists’. To the revolutionary generation, such institutions represented a corrupt old order which had to be exorcized.

As the new century dawned, these feelings were not restricted to the political extremists alone; W. B. Yeats, writing in the United Irishman in 1901, conjured up an undercurrent of revolutionary initiates bent on overthrowing a decadent modern civilization, working among the multitude as if ‘upon some secret errand’.7 But, at this point in his life, Yeats expected the new age to be one of spiritual revelation, rather than political transformation. Fourteen years older than MacSwiney and O’Hegarty, he had been through his Fenian period, and his own relations with many of the future revolutionaries were – to say the least – problematic. He soon became a supporter of Redmond’s Home Rulers, along with the majority of nationalist Irish people; the radical and separatist agenda of the nationalist ginger-groups that came together under the name ‘Sinn Féin’ (‘We Ourselves’) in the early 1900s seemed alien to him. But when he witnessed the fallout of the 1916 Rising, he realized he had seen ‘a world one has worked with or against for years suddenly overwhelmed. As yet one knows nothing of the future except that it must be very unlike the past.’8 The poem in which he interrogated the revolutionary act, and those who made it, became canonical. The reality of the Rising jolted his assumption that Ireland had settled into an everyday mode. In 1914 he had told an American audience that the age of heroics was past:

There was a time when every young man asked himself if he were not willing to die for his country. Ireland was his sweetheart, his mistress, the love of his life, for whom he faced death triumphantly. That is the theme of my [1902 play] ‘Kathleen ni Houlihan’. And it is not over-drawn, as those who know Ireland may attest. But Ireland has changed. The patriotism of the Irish is the same, but the expression of it is different. The boy who used to want to die for Ireland now goes into a rage because the dispensary doctor in County Clare has been elected by a fraud. Ireland is no longer a sweetheart but a house to be set in order.9

Two years later, his poem ‘Easter 1916’ recalled that anti-heroic mood before the insurrection, when people lived ‘where motley is worn’, denoting the style of the clown in commedia dell’arte: a world of exaggeration where no one really means what they say. But the people invoked in the poem, the makers of revolution, turn out to inhabit a different, internal world, expressed in their ‘vivid faces’. As it happens, Yeats knew many of them, some since his Dublin youth twenty years before. He had debated with them in the Arts Club, quarrelled with them in the columns of the nationalist press, even been involved in a jealous love-triangle with one of the leaders, John MacBride. Several of the leading revolutionaries were middle-class intellectuals like himself, at home in the slightly Bohemian circles of Dublin’s literary and theatrical world. The fact of the attempted revolution, for which the leaders paid with their lives, had changed them utterly; but Yeats was as astonished as most moderate nationalists that it had come to this. That feeling of astonishment has, in a sense, persisted.

‘Easter 1916’ is also a poem about biography, providing thumbnail sketches of several people whose names will recur in this book, including the upper-class rebel Constance Markievicz, the poet and university lecturer Thomas MacDonagh, and the schoolteacher and revolutionary ideologue Patrick Pearse. But to recapture the sense of a generation at a time of flux, we need to look at the minds and attitudes of a wider range of actors. For many young, obscure Irish people in the opening years of the new century shared a sense that change was afoot, and that their generation would embody it. In 1905 yet another young Cork nationalist in MacSwiney’s circle, Liam de Róiste, confided to his diary:

I often wonder whether there has been an actual, objective change of affairs, or of general ideas in Ireland during the past decade that makes things seem different to me now from what they did three, four, five years ago. Or, is it a change of ideas within myself, the inevitable change from boyhood to youth, from youth to manhood? I presume both are working. I am changing and things around me change.10

Along with many of his generation, de Róiste sensed that he was living at a time of flux, of transformation that could take place both personally and nationally. (He had, for one thing, already changed his name to its Gaelic version, having been born William Roche: many like-minded people in this era did the same.) And it is now possible to look at the making of revolutionaries, often from unlikely material, or in unlikely locations – the way that they become a ‘revolutionary generation’.

The concept of a ‘generation’ is both fertile and troublesome, especially when linked to a change of political consciousness.11 Rather than simply defining a twenty-five or thirty-year cohort, occurring in immovable chronological order, the notion has become a more fluid concept: a group or groups, not necessarily made up of people born at the same time, who conceive of themselves as bonded together by cultural mentality and social circumstance. And, following the fashions of historiography as well as changes in the wider world, we may now be coming to see the notion of ‘generationism’ challenging or even replacing class as an organizing principle of analysis: conceiving of age groups as carriers of intellectual and organizational alternatives to the status quo, acting under the constellation of factors prevalent at the time of their birth. Significantly ‘the problem of generations’ was decisively rethought in the decade after the First World War; it has since been applied to the Risorgimento generation in Italy, and a ‘generation of 1914’ across Europe. Similarly we might perhaps discern a ‘generation of 1916’ in Ireland, reacting against their fathers. To become a revolutionary soldier in the Irish Republican Army, Ernie O’Malley later recalled, was in its way a revolt against ‘the wise domination of age, to some hard and harsh in the soul as the cancer of foreign rule’. Throwing off the traces was ‘an adventure and a relief’.12

This was recognized very early on – as was the opposing strength of ancestor-worship. An astute observer noted in 1919:

The revolt of the new generation against the supremacy of the old, which has become the stock theme of the later English dramatists, is still on the other side of the Irish Sea a revolutionary doctrine almost as subversive as Bolshevism. A man’s duty is not only to do what his parents wish, but to think as they think, not necessarily because it is right, but because it is a command . . . It is difficult as yet to say in what degree the victory of Sinn Féin represents a triumph of youth over crabbed age, and whether the clash of opinion will affect other than political issues.13

The history of the revolution and its aftermath suggests that this did not happen, and a reassertion of traditional attitudes would be – in Ireland as elsewhere – a powerful theme in the history of the 1920s.

The danger of generalization across a generation must be guarded against; even a self-conceived generation can contain within it so-called ‘generation-units’ which are in apparent disagreement in some ways, but linked by affinities of response to their social and historical circumstances. Still, there is at least one way in which these larger European frameworks can be applied to Ireland. Generations are largely recognized in retrospect: this is the sense in which they are ‘not born, but made’.14 And a generation is made not only by conscious processes of identification and rejection in the lives of the protagonists, but also retrospectively, in their memories, and in their control of the larger territory of official and social memory.

The changes that convulse society do not appear from nowhere; they happen first in people’s minds, and through the construction of a shared culture, which can be the culture of a minority, rather than a majority. In Ireland, as elsewhere, discontented and energetic young men and women, whose education often left them facing limited opportunities with a sense of frustration, turned their attention to critically assessing the status quo. Out of such material a vanguard may be created, uniting several ‘generation-units’. There is also the important factor of geographical concentration, notably in Dublin. The accounts, letters, diaries and reflections of the revolutionary generation conjure up an intimate but complex city, with certain areas defined by political subcultures: a geography of radical Dublin. Radicals encountered each other in certain small shops and restaurants around Sackville (now O’Connell) Street and Rutland Square (now Parnell Square), radiating from Nelson’s Pillar. Such places sold radical newspapers and afforded meeting places, in close proximity to the premises which Yeats’s celebrated friend and muse Maud Gonne rented in North Great Georges Street to house her radical women’s organization, Inghinidhe na hÉireann (‘Daughters of Ireland’), as well as the Fenian-inspired Dungannon clubs.

It was a narrow circuit. On a brief jaunt to Dublin from her Waterford home in January 1911, the 23-year-old nationalist Rosamond Jacob first made her way to her Quaker relations, the Webbs, in Brighton Square, Rathgar, where she met the radical-artistic bon ton, including the painter Sarah Purser and the academic Charles Oldham. Later she set off with Elizabeth Somers to the Inghinidhe rooms – six flights up, piles of the radical feminist journal Bean na hÉireann on the floor, pin-ups of Maud Gonne and ‘John Brennan’ (the journalist Sydney Gifford) on the walls, the latter in narrow skirts and smoking a cigarette. Jacob went on to inspect Hugh Lane’s new gallery for modern art in Harcourt Street, and dined at the vegetarian restaurant in Westland Row (there were at least two such establishments in Edwardian Dublin). Later she met her friend Edith White, a schools inspector and Gaelic enthusiast, at the Café Cairo in Grafton Street, and ordered some cream hopsack material at Kellett’s drapery store to make herself a ‘national costume’. Evening entertainments included a soirée at the Vegetarian Society, with harp music, and a Gaelic League céilidh (an evening of Irish dancing and music).15 On a later visit that same year she stayed with Constance Markievicz, bought cigarettes at Tom Clarke’s paper-shop in Great Britain Street (the drop-off point for most IRB activity in Dublin; now Parnell Street), went to a lecture by Patrick Pearse, and was smitten with the Irish Republican Brotherhood organizer and newspaper manager Seán MacDermott (‘very young and distinctly handsome, with black hair and large dark eyes’).16 All these people would play leading parts in 1916.

With similar immediacy, the unpublished autobiography of the republican activist and academic Michael Hayes delineates a network of like-minded nationalist families living around the Clanbrassil Street area of the south city, extending into Harold’s Cross, and the local church halls and pub rooms where IRB-related organizations met, and infiltrating the notably nationalist Christian Brothers school in the area. Further up the social scale, there were certain respectable streets in the southern suburbs of Rathmines, Rathgar and Ranelagh where middle-class radicals clustered, such as Belgrave Road, with the journalists Francis and Hanna Sheehy-Skeffington, the doctor and medical campaigner Kathleen Lynn and her partner Madeleine ffrench-Mullen; or Oakley Road, with the Pearse family, Éamonn and Áine Ceannt, Thomas MacDonagh and his wife Muriel; or Harcourt Terrace, where the cultural and artistic literati such as the Coffey family, Sarah Purser, the librarian Thomas Lister, the writer and Gaelic League founder Douglas Hyde and the republican solicitor and writer Ned Stephens lived side by side.

In his unpublished memoir, the republican activist and lawyer Kevin O’Shiel discerned ‘five different Dublins’ around 1910, besides the world of studentdom which he inhabited as an (unusual) nationalist at Trinity College, Dublin. There was ‘Castle Dublin’, with its government officials, police and law officers, and so on, which he saw as ‘a ruling caste’, living an Olympian and largely exclusive existence – though under the Home Ruler Viceroy and Vicereine, the Marquis and Marchioness of Aberdeen, some grappling-hooks were thrown out to middle-class Catholics. Then there was the professional world of lawyers, doctors and university people; the ‘intelligentsia’ of writers and artists, ‘a powerful though limited Bohemia, radiating much influence on national and metropolitan thought and politics’; the commercial world; the world of local ward politics; and, surrounding them all, the vast and hardly known world of proletarian Dublin in tenements and narrow streets. There may have been many more Dublins, but they all intersected in a smaller space, and overlapped perhaps more than O’Shiel may have recognized or remembered.17 Nonetheless, radical nationalists sustained themselves in a self-referencing world which conceived of itself in opposition to all of the above.

III

But, with the exception of the imposing neoclassical bulk of the General Post Office, dominating Sackville Street and its immediate environs, where the first act of the 1916 Rising would be unveiled, the city is not where the remembered, iconic revolution was imagined and re-enacted afterwards. The conventional image of the Irish revolution is preserved in Seán Keating’s paintings from the 1920s on, where Soviet realism meets Gaelic idealization: peasants with rifles. The Irish landscape itself played a powerful part in radical-nationalist consciousness, echoing a theme long implanted in romantic sensibility. When Rosamond Jacob searched for wildflowers in the woods above the Suir Estuary and walked in the Comeragh mountains, or when Terence MacSwiney cycled to the mountain lake at Gougane Barra and recalled every impression in the trembling and exalted prose of his diary, or when F. J. Bigger filled his motor-car with excited antiquarians and explored the Antrim Glens, they recorded a high-voltage connection with landscape which was at once sensual, romantic and – in a real sense – ideological. As with Ernie O’Malley’s later memories of bivouacking on Tipperary mountainsides, or William Bulfin’s much read Rambles in Eirinn, they invoked a sense of authenticity and belonging. This access to a pre-lapsarian Irishness, through immersion in an unspoilt landscape, was also a vital part of the revolutionary generation’s experience at Gaelic League summer-schools, as will be seen below. And those who appreciated it most passionately were usually radicalized in urban contexts, and often nurtured a sense of outsider status, by descent, class or religion.

These middle-class revolutionaries may have had more in common with their Russian contemporaries than is usually imagined, different though their ideologies were. Both Irish and Russians represent a generation bent on self-transformation; both had a sense of deep differentiation from their parents’ generation; both were affected by currents of religious purism which became diverted into other channels; both would move from an era of artistic, social and sexual experimentation into one of repressive conservatism. However, this comparison should not be pushed too far. In a valuable study of Ireland published in English in 1911, and closely read by the revolutionary generation, the French sociologist L. Paul-Dubois reflected on the differences between revolutionary Irish nationalism and its nineteenth-century Continental predecessors.

Of Continental Anarchism [the Irish Physical Force Party] has no strain, except in those desperate moments in which it has practically lapsed into anarchism. It has not for psychological basis the spirit of revolt against fact, nor the primitive design of destroying everything to make room for the Utopia of a new world which should proceed by spontaneous generation from the ruins of the old. Faced with the social miseries of the time, it has not, like Revolutionary Socialism, acquired the desire to substitute for an egoistic and bourgeois society a communistic and humanitarian one. It does not, like Russian Nihilism, represent the effort of an intellectual proletariat to destroy an autocracy. Nothing is further from its national aspirations than the Federalist doctrines of the Paris Commune. Nothing is more foreign to it than that first principle of Continental Socialism, the Class War . . .18

In a sense, this restrained approach to socio-economic change is borne out by the diaries, letters and reflections of the Irish revolutionary generation. The shy and punctilious young engineer Richard Mulcahy, born in 1886, emerged rather unexpectedly as a celebrated revolutionary in 1916–22 and later became a controversial general in the Free State Army. He preserved in his archives a comment by his more high-profile revolutionary comrade Michael Collins, reflecting on the outcome of the Anglo-Irish War and the Treaty of 1921:

Revolutions and political movements mostly end in disappointment and utter wreck. Ours, a difficult combination of the two, has succeeded hitherto in a manner unique in history, and for the reason that it was based on something more than mere revolutionary and political impulses – something finer, deeper and more worthy to succeed – the impulse to a nobler life, not of the meaningless, abstract, non-human kind which is all that is looked for by revolutionaries and social reform[er]s, but a human consciousness of the vital indestructible Gaelicism within us struggling to life and expression. It was this which carried us to success where previous movements failed.19

By this reading, rather in line with Paul-Dubois, racial identity trumped more abstract ideological commitments and ensured unity and success. But two thoughts occur at once. The first is the factual correction that unity was not ensured, since, with the achievement, in 1922, of the Anglo-Irish Treaty, the revolutionary movement broke bitterly apart, precipitating a violent civil war. Moreover, there was also the unwelcome fact that the revolution had turned, in some areas, into a struggle between communities as well as between republicans and the British state. This too had its European parallels.

The second difficulty with Collins’s claim is suggested by the diaries, letters and reflections of a range of middle-class revolutionaries. Some testaments, notably the diaries of young Gaelic League and separatist activists such as Piaras Béaslaí, Terence MacSwiney and Liam de Róiste, and the copious correspondence of Roger Casement, are strikingly similar in tone. They invoke not only James Clarence Mangan’s incantatory early-nineteenth-century poem of Irish national deliverance, ‘Dark Rosaleen’, but also Byronic heroes, Werther and Hamlet. They declare their ambition to ‘live and die greatly’ and make a mark in the world. Béaslaí, who grew up comfortably in a middle-class Irish community in Liverpool (son of the editor of the Catholic Times), even has a section of draft memoirs, written in his early twenties, called ‘My Boyhood: Early Deeds’. In 1904, aged twenty-three, after suffering reverses in the Bootle branch of the Gaelic League, he tells his diary:

I will assert myself! I will make my presence felt. Life is full of fields for me. Here I am a man with such an education, such a wide knowledge, and I have no value or esteem while any fool or churl or clodhopper from this to London is able to look down on me. Oh God! Can I endure it. Shall I be despised? Shall I live a poor weak puny life – I who have strength and will and a fire within me which will not rest.20

The answer, clearly, was to get to Ireland, which he fervently idealized from his childhood holidays. ‘I shall wake up the Gael, appeal to him, trust in him.’ He actually did this, working as a Gaelic League organizer, becoming known to the police and taking a prominent part in the 1916 Rising. The passionate and puritanical Terence MacSwiney, writing in the early 1900s while a commercial clerk and part-time student at the Royal University, is even more grandiloquent:

When I picture myself thus, never a truant to the fair world of the Ideal pursuing a monotonous round of study and gaining perhaps University Honours – to come forth like the other ‘geniuses’ and to go at once into obscurity and remain there, when I consider myself there in the dull grey of life with a ray from [. . .] to lighten me the fair Land of Dreams in which I love to roam, then it is I get a conception of what a misery [it] would be for me if I were not gifted with imagination, or being gifted with it disciplined it into death, for to reap its flowers one must go with it lovingly and tend it and not let it run altogether wild . . . I read and read again with pleasure undoubted much of the verse I have written. It moves me as much almost as [if] all the dreams and hopes wrapped up in it were born in reality – God grant the dearest of them may be – I do not bear to think of Life without some of them.

I cannot proceed further with this now – as I am due at the Gaelic League in an hour’s time and must have tea first.21

His friend de Róiste, a teacher at Skerry’s Commercial College, Cork, though a more equable and less high-flown character, strikes the same note – in between turning out unpublished poetry and plays, and dreaming of writing the great unwritten novel of Irish Catholic life. ‘And where is this Ego within a man? I pity myself at times, flatter myself at times. I have moods heroic, moods sublime, moods dismal and moods – blank!’ But Ireland, he believes, will redeem him.22 Such confessions, however pretentiously they read to later eyes, chime closely with young European contemporaries of the ‘generation of 1914’. And the flyer circulated by de Róiste for a meeting of one of the many societies which he organized in early-twentieth-century Cork declares a manifesto for disaffected youth:

YE WHO THINK and Ye who work; Ye who are tired of the old ideas, the useless and effete, and long for the new, COME to the Public Meeting in the Municipal Buildings tomorrow, Sunday, January 21st 1906, at 1 p.m., AND HEAR what the New Policy for Ireland, to be expounded by the Celtic Literary Society, is.23

Other personal documents indicate a slate of ideological preoccupations which extend beyond 1848-style romantic nationalism, powerful though that impulse is. Secularism, socialism, feminism, suffragism, vegetarianism, anti-vivisectionism pulse through the Bohemian circles of Dublin, and even of Waterford and Cork, in the decade before 1916. Sometimes these impulses coexist with sacrificial ultra-Catholicism and old-style Fenianism, but they may also compete or conflict with them. Rosamond Jacob was delighted by the unabashed Fenianism of speeches delivered by the IRB activists Patrick McCartan and Michael O’Rahilly (who styled himself ‘The O’Rahilly’, like a Gaelic chieftain) at a Waterford demonstration against a royal visit in May 1911. ‘It must have been a great surprise to the audience – I suppose the younger people present had never heard real nationalism talked on a public platform in their lives before, and they seemed to appreciate it.’ But at a private meeting afterwards her good impression of O’Rahilly (elegant, dark good looks, simple delivery) was torpedoed by his self-importance and above all his violently racist beliefs about American blacks. ‘It was awful. I suppose he is an anti-democratic Griffithite sort of Sinn Féiner.’24

O’Rahilly would later be one of the most celebrated combatants in the 1916 Rising, and thus placed beyond criticism. But there were other radical attitudes, and other revolutions, that never reached fruition. Whether they could have, or not, is not the point; the objective here is to recapture the expectations of that ‘pre-revolution’, if the ‘real’ revolution is taken as having started in 1916 (Ireland’s 1789). The few works that have episodically tried to do this tend to approach the revolutionaries in terms of occupational structure and geographical background.25 What comes through in these more personal profiles of the future revolutionary elite is disentitlement; frustration; provincialism; self-dramatization; and the pervasive influence of education in a profoundly Catholic manner, which involves an equally profound nationalism.

Such feelings could sometimes be mobilized by the religious organizations and orders woven deeply into the fabric of Irish life, such as the Christian Brothers, the dominant religious order in Irish education. Terence MacSwiney, educated by the Brothers, preached violent sacrifice in his writings fifteen years before he died on hunger-strike, and spent much of the time while he was attempting to lead the Easter Rising in Cork absorbed in an Irish-language edition of Thomas à Kempis – a medieval religious writer also inspirational for de Róiste and Béaslaí.26 Inside the Church, as inside the family, the turn of the century saw a conflict between generations, the younger priests embracing nationalism, to the discomfiture of their elders.27 The struggle between the generations was also reflected within the ranks of the Irish Republican Brotherhood, and lies behind the restructuring of that movement in the early 1900s through the exertions of young men such as the enthusiastic Ulster activists Bulmer Hobson and Denis McCullough.28 The fault-lines of conflict that run through Irish society and erupt at critical moments – such as the Land War of 1879–82, when tenants wrested control over their farms from landlords by means of boycott, intimidation and mass organization – have also been connected to later outbreaks of violence. But these approaches perhaps underestimate the radical mindset and contribution of students, women, intellectuals, journalists and émigrés.

The biographies of the revolutionaries suggest the need to accommodate such class and educational profiles. A middle-class or privileged background is often glossed over afterwards, notably in the cases of women, who could – and did – feel imprisoned by the limitations and expectations enforced by gender. The violently revolutionary Sighle Humphreys and her O’Rahilly cousins went to exclusive schools and lived in large Ballsbridge houses with servants and motor-cars, but chose to separate themselves from their unionist neighbours. The parents of Geraldine Plunkett and her brother Joseph, one of the ringleaders of 1916, were extremely well off and moved eccentrically between a series of large houses with plenty of servants, a lifestyle buttressed by a considerable rental income. Under Countess Plunkett’s rule, home life was erratic and often violent: Geraldine recalled ‘we always spoke under our breath, as though we were in jail’, and the children relentlessly plotted their escape.29 Reading the papers of nationalist radicals like Alice Milligan or Máire Comerford or Mabel FitzGerald (born McConnell), the sense of stultifying family background is palpable. Milligan, a Northern Protestant who edited radical journals, pioneered consciousness-raising drama and influenced several leaders of the revolution, notably MacSwiney and de Róiste, referred to herself as being ‘an internal prisoner’ of her own family. Máire Comerford, journalist and indefatigable republican hunger-striker, moved far away from a Catholic-gentry childhood of ponies and tennis parties in County Wexford. Mabel McConnell, a strong-minded and markedly attractive young Northern Protestant in full flight from her haute bourgeoise family, became radicalized at university in Belfast and then London, worked briefly as secretary to George Bernard Shaw and George Moore, and eloped with the young poet Desmond FitzGerald; she privately reflected: ‘I seem to base all my friendships in nationalism; other things are as important, but not nearly as much so.’30

Escape, for people like Mabel, could be facilitated by foreign travel. Many of the revolutionary generation followed well-established Irish routes to Continental Europe, for purposes of education, work or leisure, as well as travelling regularly across the Atlantic. Mobility, and access to faster and cheaper transport in the Edwardian age, created new opportunities for evading the world of their parents. Others, such as Rosamond Jacob, questioned the assumptions of their background while still trapped in it. The plain, intense, uncompromising child of free-thinking parents, she wrote copious diaries recording her frustration with bourgeois provincial life, a powerful sense of thwarted sexual longing, alienation both from her Quaker background and from the dominant Catholic ethos, and her implacable determination to break into another world. A passionate cult of Irish republicanism and Fenianism provided one route, and the cultural and social sphere opened up by membership of the Gaelic League another. In classic back-to-the-people mode, Jacob records her attempts to learn Irish, to seek out like-minded people, and to make the contacts which would bring her from sleepy Waterford, where ‘anything Irish spells disaster’, into revolutionary nationalist circles in Dublin, and the glamorous ambience of Constance Markievicz and Maud Gonne.31 In this world, she searched for similarly secularist thinkers, though she was often disappointed: her robust if rather reductionist belief that ‘the Catholic church is one of the greatest influences for evil in the world’, and that it was ‘incomprehensible how any sane person of any intelligence could be a Catholic’, did not always meet with approval among her new nationalist companions.32 Certainly not among the MacSwiney family in Cork – Terence, and his sisters Mary and Annie. The fervent devotion of Terence’s diaries is exceptional even for the time. He seeks advice about the propriety of reading Tolstoy because of the Russian’s religious unconventionality, and records his anxious hopes and speculations as to which of his friends might have a religious vocation. A total abstainer, he avoided mixed company except for patriotic purposes, and inveighed against ‘beastly sensual passion’.33 Yet he also believed in the transformative power of radical theatre and worshipped Ibsen.

A decade later, Terence would become celebrated as a nationalist martyr, dying on hunger-strike in 1920; his sisters remained irreconcilable republicans all their lives, while his widow, Muriel, a daughter of the hugely wealthy brewing and distilling Murphy dynasty, followed a yet more radical course, moving to Germany and then France, and embracing communism with all the fervency with which she had espoused republican nationalism. Her testimony to an American commission on conditions in Ireland in 1920 emphasized her sense of being part of a special generation:

my parents are not quite like myself. I think I am rather characteristic of a certain section in Ireland. The younger people in Ireland have been thinking in a way that some of the older ones have not . . . They wished to belong to England. They were well off and quite comfortable and thought only of themselves. That is dying out now. The younger members of such families are Republican . . . I am only characteristic of a great many who were brought up shut up at home. And still the Irish spirit comes out of them in spite of everything.34

The large family of Ryan sisters from Tomcoole, County Wexford, who will recur in this story, came from a different background from Muriel, and stayed close to their parents, but they too struck out on a new path. The high-spirited daughters of a ‘strong-farmer’ family which believed fervently in education for girls as well as boys, they travelled abroad, worked as teachers, scientists and university lecturers, and shared the sense of making a new world. Like many of the revolutionary elite, they had become radicalized when living and working in England; other examples include Mary MacSwiney, P. S. O’Hegarty, Michael Collins and Mabel FitzGerald. Yet what linked these disparate people was – and here we might remember the observations of Paul-Dubois – Anglophobia. Rosamond Jacob on visits to England wrote contemptuously of everything from the landscape to the faces of people in the street, and in 1913 violently disagreed with the argument of the Labour leader Jim Larkin that the interests of the working classes of both countries were the same; this implied, she thought, ‘a revolting unwholesome Englishness’.35 Diarmuid Coffey, far from a revolutionary, told his girlfriend Cesca Trench that the point of independence was ‘to be able to hate the English comfortably from a position in which they can’t look d—d superior and smile’.36

Mabel FitzGerald, after sojourns in London and Brittany, returned to Ireland and became deeply involved in the separatist cause. She wrote to her ex-employer George Bernard Shaw in 1914, from the wilds of County Kerry. Here, she told Shaw, she was bringing up her son to speak Irish, and to adopt ‘the sound traditional hatred of England and all her ways; you should just hear him say “Sasanach” [Englishman], the concentrated hate in his voice is worthy of Drury Lane.’ Shaw riposted with an affectionate but hard-hitting reply. ‘As an Ulsterwoman, you must be aware that if you bring up your son to hate anybody except a Papist, you will go to hell . . . You must be a wicked devil to load a child’s innocent soul with a burden of old hatreds and rancours that Ireland is sick of . . . You make that boy a good International Socialist – a good Catholic, in fact, in the true sense – and make him understand that the English are far more oppressed than any folk he has ever seen in Ireland by the same forces that have oppressed Ireland in the past.’37

Shaw also told Mabel that ‘he who is master of the English language is master of the world’, and jeered that Gaelic revivalism ‘is not Irish; it was invented in Bedford Park, London, W’ (a palpable hit at his old adversary W. B. Yeats). Mabel’s sense of the Irish zeitgeist in 1914 was more acute than his, but his accusation that she was ‘a born Orangewoman who is also a bit of a spoilt beauty’ and ‘an educated woman trying to live the life of a peasant’ must have struck home. There is indeed something very narodnik about the life she and many of the ‘generation of 1916’ were trying to lead at the time – searching, like Russian radicals, for authenticity in rural life and hoping that the uncorrupted values of the Irish peasantry would somehow rub off on them.38 As will be seen in the next chapter, the Gaelic League’s summer-schools in Irish-speaking parts of the country (Ring, County Waterford, Cloghaneely, County Donegal, Ballingeary, County Cork) provided a transformative function for young people from city suburbs and acted as forcing-houses for separatist beliefs. As Shaw saw, the revolutionary mindset characteristic of educated and intelligent people repudiating the prejudices of their upbringing required several kinds of repudiation (which might, he warned Mabel, rebound against her when her own son rebelled: ‘nothing educates a man like the desire to free himself by proving that everything his parents say is wrong’). The Russian exile Alexander Herzen, who knew about revolutions, remarked some time before: ‘To be the scourge, the executioner of God, one needs naive faith, the simplicity of ignorance, wild fanaticism, a pure, uncontaminated, childlike quality of thought.’39 This characteristic can be discerned in Rosamond Jacob’s friend Edith White: ‘a most extraordinary person, far the most interesting Gaelic Leaguer I ever met, not that that is saying much.’ White was a schools inspector who believed in fairies, earth-spirits and vegetarianism as well as Gaelicism; she had left behind her glum Methodist background but hated the Catholic Church and believed that priests were trained in techniques of mass hypnosis.40 Edith had been a ‘rebel in everything from her birth’, and when her mother burned her Irish texts, she retaliated by rechristening herself Máire; but when Edith/Máire discovered Theosophy, she dropped nationalism as a parochial irrelevance, to Jacob’s lasting disillusionment. Similar figures, such as the mystic-minded writer of fairy stories Ella Young, kept the faith, along with the belief in earth-spirits (though, in her case, moving to California probably helped).

Crucially, the revolutionary generation was bent on self-transformation, sometimes achieving it quite spectacularly. In ‘Easter 1916’ Yeats apostrophizes a woman who, in his opinion, spent her days in ignorant goodwill and her nights in argument. This was Constance Markievicz, born Constance Gore-Booth to an aristocratic family with a great house – Lissadell – near Sligo, where Yeats met her and her sister, Eva, in the early 1890s. But in later years she followed a track that strongly recalls those Russian revolutionaries that Venturi describes as ‘repentant gentry’. She went to art school in London and Paris, where she met and married a Polish painter, Casimir Dunin Markievicz, who may or may not have been a count.41 Back in Dublin, she moved into the worlds of agitprop theatre and radical politics, eventually becoming a socialist. That is where Rosamond Jacob, torn between fascination and disapproval, encountered her: she features hilariously in Jacob’s diaries, presiding over a dishevelled household, dressed theatrically and smoking like a chimney. Markievicz easily espoused the idea of physical violence, telling Jacob impatiently that shooting was easy – ‘if you can shoot straight with an air-gun you can do the same with a rifle.’42 Her main contribution to the pre-revolution was to found a movement of military boy scouts, the Fianna, many of whom would later handle rifles in the Irish Volunteers, rechristened during the revolution the ‘Irish Republican Army’, or the ‘IRA’.

In some ways Markievicz seems like a one-off, and her eccentricity and stridency were mocked by others besides Yeats; even her comrades in arms referred to her as ‘the Loony’. Some elements of her Ascendancy background adhered. Diarmuid Coffey’s diaries record Constance and Casimir hosting annual shooting-parties at Lissadell right up to 1916 – when she went after bigger game and allegedly shot a policeman. But Markievicz was a more serious person (and politician) than is often remembered. She is also representative of a small band of Ascendancy rebels – often women, whose reaction against the Establishment they were born into is partly compounded of guilt, and partly of feminist frustration (many of them were also involved in the contemporary suffrage movement). Albinia Brodrick, sister of the Earl of Midleton, is another; she rechristened herself ‘Gobnait ní Bruadair’ and became a stalwart of the most irreconcilable wing of Sinn Féin.43

As one looks at the revolutionary generation, these figures recur. Very often, like Markievicz, they had been to art school – which seems to have had a distinctly radicalizing effect. It certainly affected four sisters from Dublin’s upper middle class, the Giffords. Coming from a strict unionist background, they all became revolutionaries: Rosamond Jacob’s diary describes the way they used their parents’ absences to smuggle ‘contraband friends’ into an impeccably unionist house in Temple Villas, Rathmines.44 One sister, Sydney, was an influential journalist, writing revolutionary propaganda under the name ‘John Brennan’. Grace was an accomplished political artist, whose cartoons recorded the conflicts and personalities of the revolution; the artist William Orpen, who taught her, painted a dazzling portrait of Grace as emblematic of ‘Young Ireland’ in 1907, and she went on to marry the 1916 revolutionary Joseph Plunkett in his condemned cell. The husband of another sister, Muriel, was Thomas MacDonagh, who would also be executed in 1916, and who had taught in the influential nationalist school founded by Patrick Pearse, St Enda’s. Like Constance Markievicz, both men feature in Yeats’s poem about 1916. Pearse, a fascinating and divisive figure, came late to revolutionary politics, but had long been at the forefront of cultural politics – as editor of the Gaelic League’s journal, and a powerful advocate of the revival of the Irish language. He also wrote poetry and plays, mostly in Irish, of a propagandist bent. Charismatic, inefficient and driven by complex personal urges, he focused his energies on education, adopting some radical child-centred ideas but also creating a kind of madrasa of revolutionary nationalism in his school. Here, Pearse preached the necessity of personal sacrifice, using as his models the heroes of Irish sagas and the theology of Christian mysticism. His work not only magnetized the children of nationalist intellectuals, but also built up a cadre of unconventional young teachers such as MacDonagh (who repudiated conventional Catholicism in favour of a sort of Neoplatonic mysticism). Pearse and MacDonagh represent vital aspects of the radicalization process: education and language, which will be considered later in this book. And the accusatory opening sentence of Pearse’s 1915 essay ‘Ghosts’ is quintessentially ‘generation of 1916’, in claiming that the old men had failed both Ireland and their inheritors. ‘There has been nothing more terrible in Irish history than the failure of the last generation.’45

The final person held up in Yeats’s poem as emblematic of revolutionary transformation does not, like the others, come from the middle-class intellectuals or the repentant gentry; but the choice of John MacBride has its own resonance, especially in personal terms.

This other man I had dreamed

A drunken, vainglorious lout.

He had done most bitter wrong

To some who are near my heart,

Yet I number him in the song;

He, too, has resigned his part

In the casual comedy;

He, too, has been changed in his turn,

Transformed utterly:

A terrible beauty is born.

MacBride – a Fenian, from a small farming and shopkeeping Mayo background, who had fought against the British in South Africa – had married Yeats’s great unattained love, Maud Gonne, in 1903, a year when she was also received into the Catholic Church. (Called on to renounce all heresies, she told Yeats, ‘I said I hated nothing in the world but the British Empire which I looked on as the outward symbol of Satan in the world . . . In this form I made my solemn Abjuration of Anglicanism & declaration of hatred of England.’46) After this marriage of ideological conviction, in which two revolutionaries came together to swear confusion to the British Empire, they briefly became a poster couple for radical Irish nationalism before the marriage collapsed in bitter recrimination in 1906. MacBride represents, like Tom Clarke, the Fenian beliefs and attitudes of nineteenth-century tradition. Somewhat at odds with ideologues such as Plunkett, Pearse, MacDonagh and even Markievicz, he had more in common with the IRB architects of revolution who do not appear in the ‘Easter 1916’, Tom Clarke and Seán MacDermott. Yeats’s poem profiled the renegade aristocrat, the charismatic mentor of the young, the literary intellectual and the violent man of action: symbolic figures in every classic revolution. But the 1916 insurrection owed at least as much to Fenian conspirators like MacDermott and to the brilliant socialist ideologue James Connolly – a combative, volatile autodidact, radicalized in an impoverished Edinburgh youth and, like many other activists, an incomer into the crucible of Irish politics at the turn of the century. The part played by socialist beliefs and labour activism in the pre-revolutionary mindset can too easily be forgotten, given the drastic restabilization of politics in a Catholic-nationalist mould during the War of Independence and after.

IV

The culture of pre-revolution may be explored through these emblematic figures and their intersections. There are structures of intermarriage, drawing networks of friends, lovers, sisters, cousins even closer.47 The Ryan family, Douglas and Madeleine ffrench-Mullen, Terence MacSwiney and his sisters, the Plunkett brothers and sisters, the Giffords, Robert and Dulcibella Barton (reacting against their Wicklow Ascendancy family), and Rosamond and Tom Jacob in Waterford – all supported each other as siblings as well as fellow separatists. They reflected that enclosed, self-referencing, hectic world which the revolutionaries inhabited; it is one of the reasons why the split over the Treaty was particularly traumatic. Such linkages penetrated unlikely sectors of Dublin’s upper middle class such as the Plunkett family, resident in grandest Fitzwilliam Square, with servants living in the attics and working in the basements, French governesses and holidays abroad. Their dilettante father – a papal count and director of the National Museum – was sustained by the riches of a great Dublin building fortune; the children, Joseph and Geraldine, set up house together in another Plunkett property, on suburban Marlborough Road, and turned it into a kind of revolutionary cell, printing a radical magazine from their front drawing room and later stockpiling weapons and ammunition. Their mother owned a farm on the edge of Dublin, in Kimmage, which became a combination of radical commune and armed camp for Constance Markievicz’s troop of nationalist boy scouts, the Fianna. The atmosphere of these places was vital to the process of revolutionary indoctrination, but it should also be remembered that they were established by moneyed privilege. Yet bizarrely, in an unpublished draft memoir, Geraldine recorded that in Ireland before 1916 the metaphor of ‘slavery’ to describe Ireland’s position ‘was not a poetic fiction; it was an actual fact’.48 There are other sorts of compensation mechanisms than those born of economic and social frustration. Elsewhere Geraldine Plunkett recalled how her experiences at medical school in 1910 led her away from the ‘shabby-genteel professional people’ that she despised, and into the circles of young men and women up from the country: their manners and accents were strange to her, ‘but they were alive, they were the coming generation’.49 As discussed later in this book, the student world of the National University embodied many radicalizing influences and connections.

The nationalist culture of Terence MacSwiney and his family was grounded in a less entitled and more aspirant ethos. Living in Cork, though from a partly English background, they found their social and career expectations baulked by their father’s early death, and their preoccupation with education, self-betterment and a desire for a public role pulses through Terence’s diaries and his sisters’ correspondence. He went to night-school, and his sisters became teachers or nuns. The same desire for educational self-betterment similarly drove the career of Terence’s friend Liam de Róiste, from a small farm on the shores of Cork Harbour; he worked for the Cork Industrial Development Association, teaching Irish at night-school while devoting every spare minute to nationalist clubs and societies in Cork. (Like de Róiste, many of the revolutionaries came from families with a dead or absent father, including Terence MacSwiney, Seán and P. S. O’Hegarty, Éamon de Valera, Erskine Childers and Patrick Pearse). Provincial autodidacts such as MacSwiney and de Róiste were fascinated by theatre and were obsessive readers, but their reverence for Shakespeare and Ibsen, and a taste for amateur dramatics, did not extend to unqualified approval of Yeats and the Literary Revival – an antipathy which, strangely, united many of the revolutionaries. The hieratic, didactic and elite elements of Yeats’s literary persona grated on them, and so did the metropolitan cultural revivalists’ repudiation of simplistic nationalist rhetoric; Yeats tried to exclude such reductionist dogma from his Abbey Theatre. Freethinker as she was, Rosamond Jacob hated J. M. Synge’s explosively subversive plays, and Geraldine Plunkett wrote menacingly: ‘It would require a large and brutal book to explain the mentality of the Abbey directorate.’50 Yet theatre, as will be seen later, was a recognized and vital forum for the cultural propaganda of nationalism.

Drama could also unleash excesses of conventional religious reaction, but the religious consciousness of the revolutionary generation was not a straightforward matter. The notion of sacrifice recurs insistently in Terence MacSwiney’s diaries, often expressed in baroquely religious imagery. When the real revolution was set in motion and claimed lives, the language of religion came naturally to its supporters. The executions of the revolutionary leaders are generally held to have begun the shift towards endorsement of revolutionary violence among a wider sector of the population; but Máire Comerford disagreed, holding that it was the initial sacrifice of the individuals concerned that affected public opinion, even before their execution. Reading contemporary accounts suggests that she may be right.

When Yeats completed ‘Easter 1916’ in the September of that year, the next phase of the revolution still hung in the balance; but by the beginning of 1919 a guerrilla war had sputtered into life, and until the truce and Treaty of 1921 the Irish countryside would be racked by violence between IRA gunmen and the forces of the police and army, while those quiet Dublin streets conjured up at the beginning of Yeats’s poem would be ‘changed utterly’ in their way. This will be outlined in the closing chapters of this book. What happened in Ireland during these years is not very often instanced in general ‘revolutionary theory’ – perhaps because it took place on a small scale and, though largely successful in displacing the established order, replaced that order with a socially and politically conservative ethos. This is, however, part of the general pattern: revolutionaries, having symbolically killed their fathers, become ‘founding fathers’ themselves. The conclusion of a recent book about generations and political culture is apposite. ‘Founding fathers, itself a generational concept, play a critical role in constructing a generational consciousness that seeks to impose cultural unity on disparate groups and constructs a national consciousness that tends to be exclusionary towards latecomers or women.’51 This statement, very relevant to Ireland, was anticipated more pithily by Kevin O’Higgins, one of the dominant politicians of the new order. ‘We were probably the most conservative-minded revolutionaries that ever put through a successful revolution.’52

What had their revolution been about, regarding objective interests? As the leader of constitutional nationalism John Redmond had pointed out in his 1915 speech, by 1900 the struggle over the land was effectively won, and it could be argued that the form of British government was neither unduly oppressive nor unrepresentative: indeed, the prospect of Britain granting self-government, or ‘Home Rule’, to Ireland seemed inevitable.53 The government’s pusillanimous response to Ulster’s resistance from 1912 changed things; but a revolutionary mindset existed well before 1912–14 and presented the makings of a revolutionary opportunity. In Ireland, as in other pre-revolutionary cultures, attention should be paid – as Yeats knew – to the radical potential of the ‘middle strata’ of society. We do not have a contemporary Irish source such as the survey of young people’s attitudes conducted by Massis and de Tarde in France in 1912, on which so many ideas about the ‘generation of 1914’ were based.54 But it is possible to try to recapture how they thought. More attention might also be paid to the portfolio of radical causes taken up by middle-class Irishwomen in the 1890s and afterwards: the associational counter-cultures that tended to be written out of Irish history in the period of post-revolutionary stabilization, but that clearly provided a conduit into radical politics, as the diaries and letters of militant Irishwomen in the pre-war era show beyond doubt. Nor do we have a source such as the questionnaire circulated among St Petersburg students in 1907–8 about sexual behaviour and attitudes; but sex was not absent from pre-revolutionary Ireland (though the founding fathers made a determined effort to control it in the post-revolutionary state). People ran away with each other to start communist communes in Donegal;55 the lesbianism of several key figures was surprisingly unabashed; and, by 1919, Rosamond Jacob was enthusiastically reading Freud on dreams and sex, and attending a series of lectures which linked sexual repression and revolutionary violence.56 By 1921, alas, that lecturer was thrown out of Dublin – a pointer for the future.

Dreams matter, if not always in the manner suggested by Freud. ‘We lived in dreams always,’ wrote the old revolutionary Denis McCullough to his comrade-in-arms and brother-in-law General Richard Mulcahy many years later; ‘we never enjoyed them. I dreamed of an Ireland that never existed and never could exist. I dreamt of the people of Ireland as a heroic people, a Gaelic people; I dreamt of Ireland as different from what I see now – not that I think I was wrong in this.’57 The Irish revolution, like the histories of its perpetrators, bristles with ironies, reversals and unanswered questions. In an unpublished memoir Michael Hayes unwittingly echoes Shaw’s riposte to Mabel FitzGerald by daringly suggesting that, for all the talk about the Gaelic League, his generation was radicalized through the English language. This is borne out by much of the journalism and correspondence of the revolutionaries, as well as by the arguments over language and identity that lasted on into the independent Irish state.

Karl Mannheim’s influential definition suggested that a political generation became ‘an actuality only where a concrete bond is created between members of a generation by their being exposed to the social and intellectual symptoms of a process of dynamic destabilization’;58 and we can see this happening in Ireland from the last decade of the nineteenth century. The policies of the British government between 1890 and 1912 certainly provoked dynamic destabilization and a revolutionary response, but by a sort of law of unintended consequences – not because they were oppressive, but because they were the reverse. It should be remembered that one reason why the revolution eventually took a conservative rather than an expropriating course was that the inequities of the Irish land system had already been addressed, by the application of government money through cumulative Land Acts from 1881 to 1909, enabling tenants to buy out their holdings. Reflecting on the revolution, Sean O’Faolain made the point that, by 1916, the panoply of Irish historical grievances, used as the rationalization for armed resistance, had become ‘purely emotional impulses’.59 But the revolutionary generation did not see it like that.

In a paradoxical outcome, when it was all over, the dispensation they had helped to bring into being was in some respects not so very different from that of their parents. In the 1920s Arthur Balfour – forty years earlier a draconian Chief Secretary of Ireland (‘Bloody Balfour’), now a philosophical retired British Prime Minister – remarked that the Ireland of today ‘is the Ireland we made’. Some of that Ireland indeed endured, and was endorsed by the post-revolutionary regime. In many important aspects, the radicalism of the pre-revolutionary era was accordingly suppressed and became a distant memory. But, from around 1900, to those who embodied the Irish radical imagination, British government seemed to be imposing on Ireland a grubby, materialistic, collaborationist, Anglicized identity, with the collusion of their parents’ generation; and that is what they fought to eradicate and replace with a purer new world.