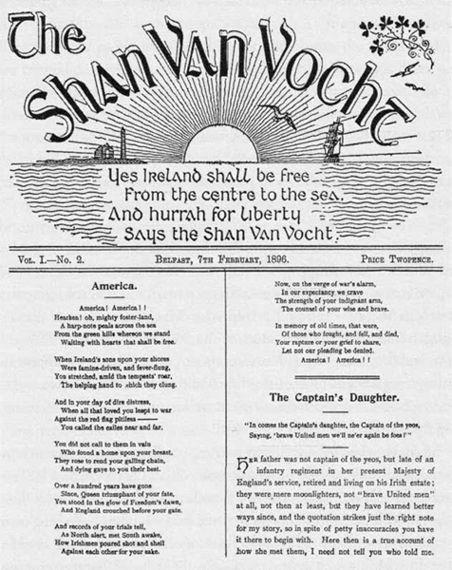

The second issue of the Shan Van Vocht, 7 February 1896, featuring the work of the editors, Anna Johnston and Alice Milligan.

The first real foundation I got for my national faith or instinct was a little ‘Life of Wolfe Tone’ by Alice Milligan . . . We separatists saturated ourselves with writings by & about the men of 1798, 1848 & 1867.

– Patrick McCartan to William Maloney, 13 November 19241

One must have lived in Ireland to understand the spell cast, in the long run, by the endless repetition of gratuitous statements.

– Sylvain Briollay, Ireland in Rebellion (1922)2

I

The twenty years or so before the Irish revolution witnessed a great upward curve in Ireland’s remarkable literary history. These are the years that saw Yeats’s arrival as the supreme poet of the Celtic Revival, with the work collected in The Wind Among the Reeds in 1899, and then the hardening and refining of his poetic voice into the sardonic eloquence of Responsibilities in 1914, along with a great flood of plays, literary criticism, stories, essays and polemic. Yeats’s books, in their beautiful bindings designed by Althea Gyles and Thomas Sturge Moore, suggest the innovation and sophistication of the high culture of the age. So do the plays of J. M. Synge, whose small but dazzling oeuvre left a comet trail across the first decade of the century, while the London stage had already welcomed Wilde’s great success and the beginning of Shaw’s. Moreover these are also the years of James Joyce’s apprenticeship, with the long gestation of Dubliners and Portrait of the Artist climaxing in their publication in 1914–15. The fiction and (unreliable) memoirs of George Moore also stand as landmarks in the period, demonstrating that Joyce was by no means the first Irish novelist to explore the interaction between sexual identity and personal fate.3

Late-Victorian and Edwardian Ireland also bred a host of other original and idiosyncratic writers such as AE, John Eglinton, Somerville and Ross, Augusta Gregory, Padraic Colum, Standish O’Grady, Daniel Corkery, Joseph Campbell, George Birmingham and James Stephens. At more populist levels, Irish novelists such as Katharine Tynan, Rosa Mulholland and Katherine Cecil Thurston catered for extremely large markets in Britain and Ireland, a world of Irish literary production rather cast in the shade by the stars of the Revival, but recently resuscitated.4

But the books read by the young revolutionaries were not necessarily those that would mark their era for posterity. The generation who came to maturity between 1890 and 1916 lived in a world where Irish writing in the English language was not only innovative, powerful and sought after by English and American publishers; it was also immersed in the political and cultural debates of the day. This was especially so in the case of Yeats, though Russell, Eglinton, Gregory and O’Grady also entered the lists. However, the print culture that galvanized the imaginations and opinions of young radicals was not, principally, that of the novels, short stories, plays and essays produced by the landmark writers who dominated the high culture of this period. It was more potently represented by the traditions of popular history mediated through journalism. The little newspapers and magazines of the nationalist fringe sometimes helped to inject the work and influence of elite writers into the general consciousness. But they more often excoriated them as politically unacceptable or counter-productive. Hard-nosed journalistic polemic rather than poetry and fiction, disseminated in a culture that was highly literate as well as politically engaged, created the influences most directly brought to bear upon the revolutionaries.

It is worth remembering that two of Yeats’s great subjects for poetry, Maud Gonne and Constance Markievicz, were much more centrally involved in the world of radical journalism than in the more rarefied circles of literary production. Tough-minded young Fenians such as Seán MacDermott or Richard Mulcahy had little time for reading Yeats or Moore, though they did go to the Abbey Theatre; the correspondence of the Ryan sisters or Seán T. O’Kelly, highly educated though they were, presents a similar picture. The same is true for Liam de Róiste and Terence MacSwiney, who looked on the Yeats circle with extreme suspicion. Their friend P. S. O’Hegarty, a passionate littérateur and bibliophile from his youth, is one of the few exceptions to this rule; unconsciously Anglophile, he believed the great poets to be ‘Shakespeare, Milton, Browning, Tennyson, Swinburne, Meredith and Yeats’.5 Synge’s drama was considered suspect by many advanced nationalists; and middle-class radicals like Hanna Sheehy-Skeffington and Rosamond Jacob found such work insufficiently political, or downright anti-national. Long afterwards, when Hanna was told of Yeats’s death in 1939 by her 22-year-old nephew Conor Cruise O’Brien, he was struck by her response.

I tried to tell her something of my generation’s sense of loss by Yeats’s death. I was genuinely moved, a little pompous, discussing a great literary event with my aunt, a well-read woman who loved poetry.

Her large, blue eyes became increasingly blank almost to the polar expression they took on in controversy. Then she relaxed a little: I was young and meant no harm. She almost audibly did not say several things that occurred to her. She wished, I know, to say something kind; she could not say anything she did not believe to be true. After a pause she spoke:

‘Yes,’ she said, ‘he was a Link with the Past.’6

So he was; but the extent to which he was central to the history of many of the revolutionary generation remains a rather moot point.

Hanna had been an influential radical journalist and was thus representative of what was essentially an alternative culture. Communication between the radicals and the outside world ran along streams of printers’ ink; and the same can be said for the vectors of communication that linked the revolutionaries to each other. When Rosamond Jacob walked down the hill from her family’s comfortable suburban terrace above Waterford city into the little streets of the town, she directed herself to the small paper-shops where she knew she could buy the United Irishman, or later Sinn Féin, or the Spark. Another young Waterford radical later itemized them: ‘Ned Cannon’s in O’Connell Street – Mrs Clancy’s, Colbeck Street, and Mrs O’Reilly’s, Parnell Street. In these shops one could obtain copies of “Nationality”, “Young Ireland” and the other papers which had long or short lives before being banned by the British.’7 In Dublin, Sydney Gifford found her path of conversion through a newspaper:

My music teacher, a mild nationalist, gave me a copy of a weekly Nationalist paper which I smuggled home and read secretly, for nothing with a Nationalist tone was allowed in our house. Shortly afterwards the well-known poet Séumas O’Sullivan, seeing me carrying the paper, offered me his copy of Arthur Griffith’s paper Sinn Féin, as something better worth reading. I began to buy Sinn Féin every week, and was soon on fire with a desire to write for it.8

She followed through this ambition, becoming a successful and influential journalist; Rosamond Jacob also became a contributor to the papers she read, and the part women played in creating radical propaganda was decisive. The theme of the contraband newspaper recurs. Richard Mulcahy, working for the Post Office in Thurles, similarly smuggled in copies of the United Irishman from 1903, and later the Republic, keeping them out of sight of his civil servant father.9 And when he came to Dublin, like so many others, his path to radicalization lay through Tom Clarke’s shop at 75A Great Britain Street, where Mulcahy knew he could buy copies of the papers with which he agreed. Sydney Gifford, though she had written for Sinn Féin for several years, had not heard of Tom Clarke until she passed its door in 1910 and noticed ‘a daring display of placards’, which, ‘defying the usual custom of newsagents of that period . . . appeared to be publicly proclaiming that he sold such papers as Sinn Féin, the Gaelic American and the most dangerous of all, Irish Freedom’. She subsequently discovered that the shop also supplied ‘a rendezvous where people went to discuss topical events, to argue on controversial subjects, or to leave messages’; it was an address, Bulmer Hobson assured F. J. Bigger in 1911, which ‘will always find me’.10

The papers edited and managed by revolutionaries such as Arthur Griffith, Bulmer Hobson and Seán MacDermott were not circulated on a samizdat basis; they took their place in a culture which fostered and harboured a vast range of journalistic products, operating over a varied market. As so often, this can be profiled for 16 June 1904 by looking at James Joyce’s Ulysses. The winding and interpenetrating quotidian journeys of Leopold Bloom and Stephen Dedalus take them through pubs where journalists are encountered and newspapers discussed, down streets where ubiquitous newsboys shout the names of their wares, into the editorial offices of the constitutional-nationalist Freeman’s Journal and the pink-paged Evening Telegraph (where they nearly meet), and on to the National Library, where George Russell, John Eglinton and others discuss the content of the magazines which they edit, such as the Irish Homestead and Dana. In the National Library too we are reminded that this is where Irish history is laid down, in newspaper records, as Bloom arrives to check the files of the Kilkenny People for the past year.11

This is all very much as it was: Aeolus, the wind-god, blew news around Dublin, and further afield, through the daily, weekly and monthly press. As we have seen in the play-going subcultures of radical Dublin, debate and controversy were fought out gladiatorially in the press; it was where Yeats learnt his youthful abilities as a polemicist.12 The world of periodicals sustained a culture of literary and political discussion, a tradition that goes back to the ‘reading-rooms’ of the Repeal movement in the 1840s, when scarce but closely conned periodicals were dispersed through discussion groups meeting in provincial towns. From the mid-1880s, the revived Young Ireland societies were promoting this approach; significantly, radical political ginger-groups called themselves the ‘Celtic Literary Society’ or the ‘Cork Literary Society’.13 Literature signified politics, as Geraldine Plunkett found to her surprise at UCD. The literary ‘economy’ was a vital agency of modernization in nineteenth- and early-twentieth-century Ireland; it was also a vital carrier of Anglicization, in the literal sense of using the English language flexibly and influentially. This was no less true when the message preached by a journal was specifically, even vitriolically, anti-English. The Irish-language input was generally kept to token columns, and the medium remained an implicit part of the message. The revolution would be conducted in English.

The tradition of wordy polemic addressed through a profuse periodical literature did not originate at the turn of the century, although the early 1900s saw a proliferation of new titles across the spectrum. A powerful and self-reinforcing relationship existed between newspapers and nationalism, from the mid-nineteenth century on.14 The Home Rule machine under Parnell had elevated journalists to positions of influence, notably through William O’Brien’s racy and widely read United Ireland. The movement also harnessed idiosyncratic provincial newspaper editors, as well as the support of the more sober Freeman’s Journal, and the services of indefatigable scribbler-MPs such as T. P. O’Connor, Justin McCarthy and J. J. O’Kelly. By the late 1890s Parnell was a tragic memory, but his ageing lieutenants still dominated the newsprint columns. Over the next generation they would be contradicted, challenged and eventually displaced by new and more radical writers and editors. But they all took their place in a tradition of literacy, wordiness and dramatic assertion; it is reflected not only in the public press but in the police reports of the time, often marked by pleasingly complex punctuation, elegant phrasing and a sense of dramatic narrative.

It has been calculated that 332 newspapers were circulating in Ireland between 1900 and 1922 (not including news-sheets or papers that originated in Britain).15 Irish demotic politics were conducted in a process of public yet intimate dialogue and exchange. With the outbreak of the First World War and the advent of the ‘mosquito press’ of subversive and satirical journals, this became almost manic, and the rhetoric reached new heights of extremism – as many establishment figures bemusedly noted. But even before this, the proliferation of titles is striking, and so – intermittently – were the circulation figures. Well-off backers (including Maud Gonne) came and went, ingenious loans were set up, advertising revenue was extracted from firms emphasizing their commitment to Irish-made produce, contributors worked for nothing, and titles succeeded each other with bewildering ease.

Sympathetic printers were no less essential than generous funders and committed journalists: Griffith’s United Irishman campaigned with especial bitterness against the Dublin printers Browne & Nolan for employing staff from Britain instead of native compositors. Seán T. O’Kelly was inducted into the IRB in 1901 by a printer, Patrick Daly, and noted how many republican initiates were connected to the trade.16 Radical periodicals and posters bore the imprint of Patrick Mahon in Yarnhall Street, or Joe Stanley’s Gaelic Press in Liffey Street, or the same proprietor’s retail ‘Art Depot’ in Mary Street, or the Irish Printing Depot, Lower Abbey Street (which also produced Ancient Irish vellum notepaper, Irish-made wrapping-paper, art calendars and so on).17 These businesses tended to operate just north of the Liffey, within easy reach of the editorial offices they served.

Alice Milligan, the pugnacious Northern pioneer of tableau theatre, was also a trail-blazer with the journal she edited with Anna Johnston (‘Ethna Carbery’) in the late 1890s, the Shan Van Vocht. The title, meaning ‘Poor Old Woman’, refers to yet another female personification of Ireland, expressed in a patriotic ballad of 1798. A vivid photograph captures the pair of young Ulsterwomen at this stage of their lives; there is a distinct air of looking for trouble. Their paper set out the classic mixture of stories, reportage, polemic, Gaelic revivalism, exemplary biographies of famous Irish people, exhortations to buy Irish-made goods, and popular history. The formula was not particularly revolutionary in itself, but this was Belfast. And the paper contained revolutionary potential: the range and vitality of advanced-nationalist journalism helped to prepare the way for the shift into open subversion from 1912.

The Shan Van Vocht, like other radical journals, often employed themes and tropes from the unpolitical press, notably romantic fiction. This afforded another avenue to those would-be contributors languishing in bourgeois households, like Rosamond Jacob, who spent many years of the pre-revolutionary era working on her novel ‘Callaghan’ and sending off stories to generally unreceptive editors. More commercially successful authors such as Katharine Tynan and Nora Hopper produced reams of stories in which love conquered across sectarian, political and national divisions (a tradition stretching back to the more substantial ‘national tales’ pioneered by Irish novelists after the Act of Union). Milligan’s tales appeared under titles such as ‘The Outlaw’s Bride’, invariably dealing with rebellious girls from privileged unionist backgrounds getting it together with sexy Catholic freedom-fighters, and daring damsels foiling bumbling British officers. These present a combination of disguised autobiography and wish-fulfilment, and articulate a poignant contrast with her own long life, full of disappointments.

Milligan has been hailed as an underrated pioneer of radical-nationalist journalism and – as seen in an earlier chapter – agit-prop drama. This is true in some ways, but her low profile in the cultural history of the period reflects the derivative and banal nature of her writing, and a congenital weakness for bathos (‘O Ireland dear, of my whole life’s love for thee/O Ireland dear, thy redemption come to thee!’18). Her work sustained a resolutely orotund Victorian flavour while contemporaries were defining new territory. Another reason for Milligan’s subordinate position in the Irish historical record may be that she adhered to the Protestant faith of her youth and was disillusioned by the clericalism and narrow-mindedness of the post-revolutionary dispensation.

But in the 1890s and early 1900s she was a key influence upon literary-minded young nationalists such as Bulmer Hobson, Patrick McCartan and Terence MacSwiney. During the 1890s she was a neighbour of F. J. Bigger on the Antrim Road, and became closely involved in the expansive cultural and political activities centred on Ardrigh. Here she met the dashing separatist Roger Casement, the revolutionary socialist James Connolly, the actor-musician Cathal O’Byrne and others. She also played a prominent part in the 1898 project of commemorating the 1798 Rising, in which Bigger was a central figure; there was a special room at Ardrigh dedicated to 1798 memorabilia, and he indefatigably searched out the graves of forgotten rebels. The Rising played an essential part in the self-definition of Northern Protestant radicals, as proof positive that their native culture held within it the potential for all-Ireland nationalism – a clear rejoinder to contemporary encouragement of Ulster unionism by the Conservative Party in Britain.19 Milligan advanced these arguments during her editorship of the Northern Patriot from October 1895, often in verses that could have come straight from Thomas Davis’s Nation in the early 1840s:

And now, when Ascendancy closed its foul reign,

And the notes of the Angelus peal o’er the plain,

Shall we suffer disunion to raise its vile head

In the long-suffering land where our fore-fathers bled?

Oh, no, ’neath the old flag united we’ll stand,

In a peaceful endeavour to lift up our land

To her long vacant place ’mid the nations again,

Nor look with distrust on the Northern Men.20

She projected the thesis more aggressively in the Shan Van Vocht, and kept up the pressure through lectures, historical discussions, plays and fiction.21 The Shan Van Vocht folded in 1899 because of financial troubles, and perhaps also because it tried to tread an editorial line of non-sectarianism and high-minded proto-Fenianism without endorsing party or factionalist politics. When Arthur Griffith took over its subscription list to begin his own paper, he would make no such mistake.

The profusion of journals read by aspiring radicals around the turn of the century did not subscribe to identical ideas. The Shan Van Vocht indicated as much by instituting a column called ‘Other People’s Opinions’, giving house-room to agendas such as James Connolly’s socialist republicanism without necessarily endorsing it. Maud Gonne was never particularly open to other people’s opinions, but she printed socialist dispatches from Connolly in Irlande Libre, dealing with social conditions in Ireland, and referred to him as ‘notre collaborateur’, while herself remaining suspicious of socialist economics – as befitted someone much involved in French radical right-wing politics. By contrast Alice Milligan inveighed against ‘anarchical methods’ and ‘bomb throwing and blowing up buildings without aim or reason’ in the Shan Van Vocht during the 1890s – clearly seeing developments on the Continent as presenting an awful warning for Ireland. Nonetheless, while ‘not at liberty to preach revolution’, the paper promised to report the doings ‘of revolutionaries, insurgents, conspirators in Matabeleland, Johannesburg, Cuba, Canada’.22 Romantic Fenianism dictated the tone of her magazine (and was probably the commitment which terminated Milligan and Carbery’s other employment as editors of the Northern Patriot). The language of soldierly preparation was frequently employed, and used to advance the idea of achieving discipline and drill through sport: ‘It is the bounden duty of every man, of every body, who dares to dream of freedom, to make himself in every way that lies in his power a soldier fit for Ireland’s service,’ declared Milligan in 1896.23 This too was prophetic.

After Milligan, many of the people who dominated the radical press in the early years of the new century are the familiar names who would come to prominence later. They include Arthur Griffith, Bulmer Hobson, Helena Molony, Seán MacDermott, P. S. O’Hegarty, Terence MacSwiney, Hanna Sheehy-Skeffington, Patrick Pearse and Maud Gonne – though some, such as Fred Ryan or D. P. Moran, would fall into obscurity or take themselves elsewhere. By far the most prominent figure was Griffith, an enigmatic man whose eventual emergence as President of the new Free State after the War of Independence would not have been forecast by many people twenty years earlier. He was born in 1871, and thus older than most of the people we have encountered, and for many of them he occupied the position of guru. His credentials were working class: born in a tenement house, he left his Christian Brothers education at twelve, was apprenticed to the printing trade, and thenceforth developed his powerful if rather narrow intellect through the National Library and reading-clubs. Already active in the little societies that sprang up during the mid-1880s, he joined the IRB – though by 1901, while his name was still on the books in the Bartholomew Teeling branch, he rarely attended meetings. Griffith was politicized by a spell in South Africa in the late 1890s; his passionate support of the Boers a few years later went with a ready suspicion of cosmopolitan financial interests and imperial conspiracies, which could shade into anti-Semitism as well as Anglophobia. But he emerged as the most rhetorically powerful Irish journalist of his time, and an original and creative political thinker.

In a series of periodicals from the turn of the century Griffith propagandized his own brand of separatist political culture, drawing highly coloured and partial lessons from Irish history: those evenings in the National Library instilled a reverence for Davis, Mitchel and the Young Irelanders that recurs throughout his journalism. His papers the United Irishman and its successor Sinn Féin embraced a wide range of contemporary causes, denouncing the genteel Irish establishment in scathing and iconoclastic prose. Griffith was passionately anti-Dreyfusard, partly from an admiration of French étatisme, partly from his own weakness for conspiracy theories featuring Jews and Freemasons, and partly because he instinctively distrusted any cause taken up by well-meaning liberals. His interest in French politics also reflected his readiness to employ imaginative parallels from abroad – most famously, the example of how Hungary had achieved dual-monarchy status under the Austrian Empire, published as the bestselling pamphlet The Resurrection of Hungary in 1904. Despite his IRB connections, Griffith kept recurring to this possibility for Ireland, suggesting a link to the crown, and pouring cold water on the feasibility of physical-force, which infuriated many on the fringes of Cumann na nGaedheal and later Sinn Féin – the umbrella-groupings of radical nationalists which he fostered and sustained. His economic priorities were strongly marketed, with batteries of statistics, in order to prove the value and potential of self-sufficiency and a vastly increased population. Griffith tended to write most of his articles himself, in a uniquely strident, scornful tone that conferred great authority; though in person he was more self-effacing, as people found when they sought him out.

Long afterwards, Richard Mulcahy tried to analyse Griffith’s influence on young nationalists around 1908, as they slowly realized that

. . . the type of home rule you were likely to get was not going to be all that you would want. When I say myself I am talking of the community or the class or the companionship that I represented. We had absorbed all Griffith’s teaching in that respect; we regarded him as our great mind and our great leader, so that we were being conditioned, not in a party political kind of a way, but we were conditioned in relation to Irish life and its development and its fostering.24

In an unpublished memoir Kevin O’Shiel described his first encounter with Griffith. As student enthusiasts, he and a friend decided that they must meet this legendary figure and went to the Ship Tavern on Middle Abbey Street, which they knew Griffith frequented. The barman obligingly pointed out ‘a small, broad-shouldered, stockily-built man, with a large moustache, drinking stout with a couple of friends’. The two undergraduates expressed their admiration of his work, which was shyly received; Griffith stood them a drink and then drifted away.25 Later, O’Shiel would become closely connected to him. But the encounter suggests the intimacy of Dublin’s small world (reminiscent of how the youthful Joyce sought out AE and Yeats); it is also notable that before meeting Griffith, his student admirers had never seen a picture of him and had no idea what he looked like. The editor who did so much to create the cult-image of figures like Maud Gonne managed to remain relatively anonymous himself.

The content of the United Irishman, as its name implies, harked back to the inspiration of 1798 which meant so much to Milligan and others, but it operated much closer to the cutting edge. (It also appeared weekly, not monthly.) The upheavals within the Irish Parliamentary Party that brought about an uneasy reunion of Parnellites and anti-Parnellites at this time, the sectarian machinations of the Ancient Order of Hibernians, the local interest-groups mobilized by the United Irish League – all were mordantly exposed and satirized, along with the inadequacies and iniquities of British government. Ireland would ‘lead the world against the bloody, rapacious and soul-shivering imperialism of England’.26 Griffith maintained a lofty and boundless contempt for the necessary compromises in which Redmond’s Irish Parliamentary Party was inevitably immersed; this analysis was an article of faith for the disparate nationalists who gathered under the resonant name of Sinn Féin. The United Irishman also acted as a kind of house newspaper for Gonne’s political women’s association, Inghinidhe na hÉireann. There was a noticeable input from female journalists, including Mary Butler, Jennie Wyse Power, Nora Hopper, Hanna Sheehy-Skeffington and especially Maud Gonne, whose money helped to bankroll the paper until the fallout from her separation from John MacBride in 1903–4. The police, who kept a close eye on the radical press, wondered how the United Irishman survived, given that the printer and publisher Bernard Doyle was ‘only a struggling man’.27 In fact, Gonne provided twenty-five shillings a week, which paid Griffith’s salary as editor, copywriter and compositor, and she also contributed the proceeds of some lecture-tours. Her own columns stressed social issues, Gaelic revivalism and examples of mythic legend and stirring prophecy, the nobility of the South African Boers, the decadence of English culture, and international conspiracies of several kinds, not least Jewish.28 Griffith’s paper also printed Gonne’s play Dawn, which reprises some of these themes, along with the iniquity of emigration as a desertion of the motherland, even at the point of starvation. The United Irishman also spread far and wide the much mythologized ‘Patriotic Children’s Treat’, which Gonne masterminded as a counter-demonstration to the royal visit in 1900 (an occasion also marked by the paper reprinting Gonne’s incendiary 1897 article about Queen Victoria, ‘The Famine Queen’: John Mitchel redivivus).

The great contrast between the United Irishman and the Shan Van Vocht was the style, quality and rebarbativeness of the writing, which was very largely Griffith’s own. Where its predecessor was flowery and Victorian, the United Irishman was uncompromisingly modern. Its editor had lived and worked abroad, was familiar with the new journalism, and had a keen eye for what was going in Europe and the Empire; he knew that the style of political journalism must be pointed, personal, deflationary and, where necessary, spiteful. Good manners had nothing to do with it. The paper also provided, in its early days, a forum for the cultural avant-garde: Yeats, George Moore, Oliver St John Gogarty, John Eglinton and Edward Martyn all published there. As we have seen, Frank Fay, later a key figure in the Abbey Theatre, was the United Irishman’s drama critic, using his columns to argue for didactic cultural nationalism – a stance he later abandoned – and several experimental plays were printed in its pages. However, this inclusive tendency, and the United Irishman’s role as flag-bearer for the dramatic avant-garde, would be compromised by the political – or unpolitical – direction taken by the Abbey Theatre under its benefactor Annie Horniman, an enemy to all things nationalist. Sympathy for dramatic experimentalism was also undercut by Griffith’s violent distaste for the plays of Synge, and above all by his firm belief that art must serve as propaganda.

Propaganda for what? One reason why readers devoured the United Irishman, and later its successor Sinn Féin (which was printing 8,000 copies a month by 191129), was that there was always a frisson concerning how far the papers advocated actual subversion of the state. The papers clearly preached separatism in an abstract, psychological and cultural sense; at the outset Griffith was still in the IRB, along with his inspirational colleague, the charismatic but short-lived William Rooney. But when it came to sentimental Fenian praise of ‘The Sword’, Griffith could on occasion be as lacerating as his rival D. P. Moran, who consistently lampooned such attitudinizing in the Leader. Bulmer Hobson’s paper the Republic was in fact founded in 1906 in order to preach unambiguous separatism, at a time when Griffith was seen to be taking dilution too far. Despite his tradition of excoriating Redmond and the parliamentarians, he was coming to be considered distinctly unsound on the question of the British monarch. Again, in marked contrast with the Shan Van Vocht, Griffith used his papers to work out for himself alternative routes to practical independence – visionary though the route might be. This was the process behind The Resurrection of Hungary: that Ireland could attain autonomy within the United Kingdom by the construction of a dual monarchy. Since this depended upon a particularly skewed and idealized version of Austro-Hungarian history (particularly where the Magyars were concerned), it was read in some quarters as a Swiftian parody.

It also infuriated old-style Fenians, to whom the idea of any connection with the British crown implied a Faustian, not to say satanic, pact. Griffith, however, would return to the idea, bolstered by his idée fixe about the 1783 Act of Renunciation, which, according to his (inaccurate) reading, made the subsequent Act of Union invalid under constitutional law. This was of a piece with the oddly academic and finger-wagging tone which could invade his columns of stirring invective: the mark of the autodidact, which never left him.

Sinn Féin was funded by sales of stock to better-off supporters; debentures were taken up by Casement, George Gavan Duffy, Michael O’Rahilly and several foreign subscribers. Its editor received two hundred pounds a year but the paper could not afford to pay its contributors. Nonetheless, they included James Stephens, Padraic Colum, Susan Mitchell, Pádraic Ó Conaire, Séumas O’Sullivan, Joseph Campbell and William Bulfin. These were distinguished commentators by any standard; most of them would become star contributors to the more highbrow Irish Review edited by Thomas MacDonagh and Joseph Plunkett a few years later.30 Less impressively, the articles by Sydney Gifford sustained the tone that had made the United Irishman popular, presenting Dublin as a decadent centre of foreign influence, where ‘the deadly Jew-made fever has crept over Grafton Street’, an infection that must be extirpated by Gaelic purism. (The influential nationalist journalist William Bulfin, in his bestselling Rambles in Eirinn, was equally unwelcoming to the idea that Jews might be tolerated in Ireland.31) But the reason why Griffith’s newspapers remained sui generis was that they presented the familiar conundrums of the British–Irish relationship from a new angle, in prose that was demotic, hard-edged and sometimes mercilessly funny. The same was true of James Connolly’s Marxist productions, though he and Griffith were ideologically many poles apart: Griffith favouring the economics of autarky and self-sufficiency, as preached by Friedrich List, and viewing international socialism as something akin to Freemasonry, a star exhibit in his capacious menagerie of bêtes noires.

Griffith’s politics were serpentine enough, but his rival D. P. Moran, who edited and wrote much of the Leader, was even more unpredictable. Excoriatingly anti-English, far more stridently Catholic than Griffith, equally contemptuous of the Irish Parliamentary Party as Anglicized parasites, but unprepared to endorse Sinn Féin’s radical alternative, he directed his eloquent and often hilarious abuse at most corners of the Irish political world. Terence MacSwiney, writing in the minuscule Cork journal Éire Óg, denounced the Leader for not living up to its anti-British pretensions, and for its ‘egotistical and dictatorial tone’; he felt it lowered the ‘dignity’ of the national cause. His friend de Róiste was similarly shocked at the ‘bitter scornful attacks’ on Sinn Féin in the Leader, correctly suspecting his colleague Daniel Corkery.32 From a different angle, secular or Protestant feminists like Rosamond Jacob and Cesca Trench loathed the Leader – ‘a hateful little paper’, in Cesca’s view, and ‘the most unpleasant and lowest down paper in the country’, according to Jacob33 – but Moran’s brilliant phrase-making and nicknames tended to stick. The Leader also had a special line in Irish self-castigation. For instance, it unexpectedly contradicted the stock-in-trade allegation, subscribed to by John Redmond as well as by the Fenian orthodoxy, that British policies had depopulated Ireland; Moran preferred to blame the Irish themselves for not patronizing native industry and culture, and selfishly emigrating in search of supposed betterment which would, he promised them, turn into Dead Sea fruit in their mouths. Moran’s ‘Philosophy of Irish Ireland’ was projected through a campaign in his columns to make people wear Irish clothes, eat Irish food and endow their children with Irish names; he scornfully described so-called nationalists setting off to Sunday Mass with ‘their recreant skins’ cast in decadent English worsteds.34 He violently attacked all manifestations of popular English culture, especially imported plays ‘where religion is besmeared; idling is glorified; cadging and thievery are presented as “smart” arts; the heroes are cads; and the heroines are – well, the modern theatre has a name for them – “women with a past”.’35

The scatter-gun abuse of the Leader was both a strength and a weakness. Events seemed to outdistance Moran, though his religious sectarianism and endorsement of petite bourgeoise values were in some ways prophetic of the post-revolutionary future. In the years up to 1916, however, it is hard to better Patrick Maume’s summing-up: ‘Moran was the fox to Griffith’s hedgehog; he lost out to Griffith in historical reputation because, while he knew many things, Griffith centred his life on one thing Moran did not take into account: the extent of nationalist discontent with the British state, and the ability of a determined minority in times of crisis to channel these discontents into a nationalist project more radical than seemed possible in 1900.’36

A different strain of polemic was reflected in W. P. Ryan’s Peasant, which was nationalist in a more sardonic and pluralist way – and also socialist, which differentiated it sharply from Griffith’s output. The Workers’ Republic (1898–1903) and the Irish Worker (1911–14) presented the ideology of the labour leaders and ‘agitators’ James Connolly and Jim Larkin to a receptive, and often surprisingly large, audience. And as the Gaelic League became more widespread and implicitly more political, its journalistic activities became more important, especially through An Claidheamh Soluis under the editorship of Patrick Pearse. The premises of the paper, originally managed by that ‘struggling man’ Bernard Doyle, moved around Dublin’s North side, from Ormond Quay to Sackville Street to Rutland Square, conveniently close to Gaelic League meeting-rooms and Tom Clarke’s shop. The advertising and editorials, as well as much of the copy, remained largely in English for several years, with Irish taking over as cultural and political issues became more prominent. This process was encouraged by a subsequent manager, Michael O’Rahilly, self-styled Gaelic aristocrat and increasingly violent separatist. His inclinations were more crudely political, and he took a dictatorial line in suggesting cartoon subjects to contributors such as Cesca Trench.

Cartoon No. 4, Wait and see. Fan go bfeicid tu. Picture of Irish Ireland (Gaidil na hÉireann), a beautiful girl lying on the ground tied hand and foot, gagged by Béarla [English]. The sword of Anglicization is piercing her through and a pool of blood has flowed from the wound. She is just making an effort to rise.

‘Cartoons like these,’ O’Rahilly added, ‘would I think be very effective but they should be very simple and easily understood. Crude rather than subtle, you understand. We of the Claidheamh have to deal with a nation of political infants.’37

At a different level from the weekly (and sometimes daily) polemical sheets were the literary journals, weekly or monthly, which were more closely connected to the world of high culture and experimental writing. These included the Irish Homestead under AE and Susan Mitchell, which, though the organ of the Co-operative Movement, carried pieces by James Joyce as well as others of AE’s protégés; its office in Merrion Square was, for moderate nationalists, a kind of alternative drop-in centre to Tom Clarke’s shop across the Liffey. It was staffed by AE, magnificently unworldly but sharp for his purposes, and the high-spirited Mitchell, whose caustic verse-parodies of well-known Dublin personalities were widely feared and treasured. The All Ireland Review, edited and largely written by the eccentric revivalist writer and prophet Standish O’Grady, similarly cast a wide cultural net, and to read it is to hear echoes of the pluralist Ireland that was central to the imagination of a certain segment of the revolutionary generation. O’Grady’s political principles followed his own apocalyptic-unionist line, alternately abusing and cajoling the landlord classes, who – he believed – held the key to Ireland’s salvation. But his literary evocation of a Carlylean world of ancient Irish heroes in books such as History of Ireland: The Heroic Period had entered the bloodstream of nationalist revivalism. The All Ireland Review preached spiritual epiphanies and denounced materialism, often through the medium of heroic serial stories, but it also afforded the editor space to reply brutally to bemused letter-writers and to address open manifestoes to those who had incurred his displeasure – notably Yeats. ‘Frankly, and quite between ourselves, I don’t like at all the way you have been going on now for a good many years. You can’t help it, I suppose, having got down into the crowd.’38

O’Grady also used his paper to preach the virtues of paganism, which he rated very highly, and to deride Catholic pieties – which cannot have helped him win a large constituency. The All Ireland Review struggled along at the mercy of O’Grady’s chaotic financial management, as he tried to treble the subscription charge while keeping the street price at threepence. ‘I regard it as a connecting link between the classes and the masses,’ he wrote, ‘the gentry and the people, the educated and those who, without being what is called educated, are a reading, considering, thinking kind of people, and who, as such, exercise an influence over considerable numbers.’39 This was a perceptive analysis of the position occupied by many young radicals; but they were not going to be persuaded by the All Ireland Review, and looked to more extreme publications.

There was also the short-lived Dana (immortalized by Joyce in Ulysses), featuring literary high culture, and the more directly political Irish Review, edited at various times by Thomas MacDonagh, Padraic Colum, Joseph Plunkett and Tom Kettle. It was founded ‘to promote the application of Irish intellect to Irish life’; when Plunkett took over from Padraic Colum in the summer of 1913, it moved to 17 Marlborough Road in Donnybrook, the suburban house where he was living with his sister Geraldine. Their mother, Countess Plunkett (who was also their landlord), provided the £150 necessary to keep the magazine going under its new editor, after the first backer withdrew his financial support. Printed by Ernest Manico in Temple Bar, it published art plates by Jack and John B. Yeats, William Orpen and AE, as well as articles and stories by James Stephens, Patrick Pearse, Joseph Campbell, Arthur Griffith, Douglas Hyde and many others. Under Plunkett, the increasingly political direction of the journal was indicated by a series of pseudonymous articles such as ‘Ireland, Germany and the Next War’ (in July 1913), in fact written by the Plunkett family friend Roger Casement.

The Irish Review continued simultaneously to provide a useful outlet for Plunkett’s and MacDonagh’s play-scripts as well as more high-falutin literary journalism than was found elsewhere. This was also catered to by the self-consciously internationalist and modern-minded Thomas Kettle, who had learnt his trade as a student journalist editing St Stephen’s at University College. Kettle, the star of his university generation, had also studied in Germany, and read widely in French and German; an early interest in Sinn Féin, and a brief fling with socialism, did not survive his reading of Nietzsche. His constitutional-nationalist political ambitions, as seen in an earlier chapter, were not harmed by his marriage to Mary Kate Ryan’s enemy Mary Sheehy, more conventional than her sister Hanna Sheehy-Skeffington. This connected him to the Irish Parliamentary Party elite, whose ranks he would eventually join. He had already tried to rejuvenate the party through the Young Ireland branch of the United Irish League, founded in November 1904. People attracted to this ginger-group, however, often found the party impervious to their efforts, and drifted to more advanced sectors of the political spectrum. Kettle’s strategy was different; like so many of his contemporaries, he started a journal, the Nationist, which lasted for six months from September 1905. ‘Nationist’ was coined in deliberate contradistinction to ‘nationalist’, and Kettle derided what he saw as the woolliness and impracticality of Griffith’s thought. The journal reflected his own interest in the growth of democracy and nationalism in Europe at large, which he applied to Ireland in a distinctly cosmopolitan way; this attracted contributors such as the feminist and pacifist Sheehy-Skeffington (whose influence soon predominated), Joyce’s friend Constantine Curran, the clever young lawyer Hugh Kennedy and the poet–playwright Padraic Colum. Unlike many of his IPP colleagues, Kettle was a passionate advocate of women’s suffrage. Arguing against Irish exceptionalism was a central theme; readers of the first issue were encouraged to accept the country as ‘a great complex fact; an organism with all the complications of modern society’.40 Like the Peasant or the All Ireland Review, it sustained a rhetoric of pluralism and scepticism. Its pages preserve an aspect of these years that would not survive the coming armageddon of revolution, civil war and the establishment of a conservative Catholic state.

The same was true of the National Democrat, published and largely written by Hanna and Francis Sheehy-Skeffington from 1907, and congratulated by one correspondent for being ‘undismayed by episcopal hostility’.41 Within Dublin, the Democrat’s initial subscribers seem to have been the middle classes of Rathmines and Rathgar, with an interest in labour and social questions;42 but the editors were anxious to extend the sales to Britain as well, and distributed the magazine through Peter Murphy, a Liverpool agent who also handled Sinn Féin, the Leader, the Republic and provincial Irish newspapers. (Murphy’s Irish Depot and Catholic Depository was the kind of commercial institution which enabled the Irish living overseas to sustain their national and religious identity; it advertised ‘Prayer Books, Beads, Statues, Holy water Fonts, Scapulars, medallions, religious books, oleographs, Irish historical and other works, pictures, views, etc., jewellery, ornaments, Blackthorns, all the leading Irish papers and a large selection of Gaelic books, and Irish manufactured stationery.’43)

To some Irish nationalists resident in England, however, the enlightening of Albion was a lost cause. One correspondent, asked by Skeffington to distribute the National Democrat, demurred on the grounds of its socialist leanings and belief in the international fellowship of the workers. ‘If the “National Democrat” advocates the claims of Ireland’s rights to “Nationhood”, I shall be pleased to help it in every positive way, but I don’t believe in appealing like a nation of beggars to the English Democracy for help or support of our clan, because they also are members of the Robber Band who plundered Ireland.’44 But employment in the Robber Band’s country was not incompatible with spreading the word. P. S. O’Hegarty, having passed his civil service examinations in 1902, used his comfortable desk job in London as a base for journalistic operations, dispatching his official work rapidly and then devoting himself to writing subversive articles.

I would not like to say how much stuff for the mosquito press I wrote in the peaceful seclusion of St Martin’s Le Grand, looking out on the inner courtyard, with sitting opposite me a Cockney, decent, cheerful, plodding and utterly devoid of imagination or alertness of mind, as only a Cockney can be, who found it nearly impossible to do his day’s work although he came in at 9 and stayed till 6.

Revisiting the office in the 1920s, O’Hegarty found his old colleague still at his desk, piled high with files. ‘I nearly sat opposite him from force of habit.’45

Back across the Irish Sea, nationalist activists in Ireland kept an eye on British opinion. Down in Cork, Liam de Róiste was sending material on Irish-Irelander activities to the Davis Press Agency, started up by O’Hegarty in West London, which supplied, in de Róiste’s words, ‘a counterblast to the news supplied by the English press agencies’ such as Reuters. ‘Very many people,’ de Róiste reflected, ‘estimate your influence and standing by the notice given you in the daily papers, though one now thinks there is sufficient knowledge [now] of how false reports can be.’46 The tireless de Róiste also acted as agent for Banba and other journals, as well as contributing notes, letters, articles and verses to W. P. Ryan’s Irish Peasant. Finally, in 1906, after dreaming of it for years, he brought out his own little journal aimed at advanced nationalists in Cork – the Shield, an eight-page monthly. De Róiste used his contacts and expertise gained in the commercial department of his hated employers, Skerry’s College, and found a sympathetic printer in Edward Mooney at the Shandon Printing Works – ‘a quiet type of man, with unusual ideas of affairs – influenced by reading English socialistic publications’.47 De Róiste’s companions in the Celtic Literary Society were, as usual, infuriatingly sceptical about his latest fad, but the first issue appeared in August and sold a thousand copies, nearly breaking even. The paper lasted into 1907, racked by financial problems, while de Róiste oscillated between black despair and euphoric hope that it might become a weekly. When the Irish Peasant was closed down at the fiat of Cardinal Logue (it had made fun of clerical pretensions), de Róiste disloyally hoped that the Shield might take it over, but his own devoutness put paid to the idea, after the usual agonies of introspection.48 He remained passionately determined to make his mark by publishing in other journals, and eventually managed to place his vast manifesto-poem, ‘Ireland Calls’, in Griffith’s Sinn Féin, covering nearly two pages with invocations which owe as much to Walt Whitman and Herbert Spencer as to James Clarence Mangan.

Men of the Irish race: men of a nation noble

Sons of mighty sires, who climbed the mountains of fame –

Climbed it o’er rough rocks and sharp; in the noble endeavour

To breathe the pure air of freedom: in the clear, bright light of the sun –

Of the sun of Justice whose beams undimmed, unsullied, unbroken,

Shine on for ever and ever, above the fleeting clouds

Of men’s ideas and opinions.

Hear ye – though weak the voice: that calls midst the noisy clamour

Of tongues that babble and babble; like the ancient builders confused.

They prate for the future glibly; and promise for men unborn

‘For ever and ever’ they promise – forgetting the nation’s soul;

Forgetting the laws of growth;

Forgetting the laws of development; the principles of existence;

The never-ending progressions; the evolutions and changes;

The expanding and extending; that mark the living things.

The twenty-fourth and final stanza left de Róiste’s readers in no doubt: ‘Better to die for an Ideal, under the standard of Right / Than compromise with Wrong, and live the life of a Harlot.’49

III

These magazines and journals reached far fewer people than the mainstream nationalist dailies such as the Freeman’s Journal and the Independent, but they helped to construct a radical alternative world-view. They also gave a voice to a wide range of talented individuals operating in spheres outside the establishment. Above all, the activities of the Sheehy-Skeffingtons highlight the importance of women journalists, and the opportunities given by periodical publishing to women denied a role elsewhere – or pressed by popular acclaim into a role which was confining as well as celebrated, as happened with Constance Markievicz and Maud Gonne. Maud Gonne’s beauty, her fondness for dramatic platform appearances and the shadow of scandal that surrounded her private life obscured her commitment to the new politics of publicity. This involved a variety of demonstration-tactics as well as an impressive amount of hard journalistic work; she was also enabled by a large private income. The far less wealthy Markievicz, on her way to socialism and already heading the Fianna, her youthful militia, was rather unfairly seen as an upper-class eccentric out for kicks. A more serious commitment is implicit in her columns in Bean na hÉireann (‘Woman of Ireland’), the journal of Gonne’s organization Inghinidhe na hÉireann, edited by Helena Molony, which ran from 1908 to 1911. Molony, a combative and talented actress with a weakness for drink, pursued a radical existence on many fronts; she had learnt her trade on James Connolly’s Workers’ Republic a decade earlier.

Journalism was also the field where in these years the women’s suffrage movement and the labour movement intersected with the politics of radical nationalism – sometimes antagonistically. Griffith remained anti-socialist, for one thing, and several nationalist agitators felt that the women’s cause should be strictly subordinated to the national issue. But the journalism of people such as Delia Larkin reminds us that in 1911 an Irish Women Workers’ Union was actually established, and that women were coming to the fore in socialist as well as in republican politics. There is a tendency to see the radical, or, more accurately, anti-establishment, press of these years as exclusively represented by Griffith and Moran, speaking through the United Irishman and the Leader – one of those binary oppositions beloved of Irish history. But the range of journals and interests, bringing in labour interests, feminism, and the socialist pluralism represented in the Sheehy-Skeffingtons’ National Democrat and W. P. Ryan’s Peasant, suggests a different and more complex picture.

The Irish Peasant, which began publication from Navan as a weekly in 1905, took a more sanguine and relaxed view of Irish possibilities than Moran’s Leader, reflecting its editor’s different personality. It was founded by James McCann, an imaginative local entrepreneur, and soon reached a far wider audience than local dissidents in County Meath. The Irish Peasant boasted two remarkable editors, first Pat Kenny and then (from December 1905) W. P. Ryan. Anti-grazier, anti-clerical and pro-industry, the journal’s opinions had to be expressed in coded language: there was no public opinion worthy of the name in Ireland, it declared, but ‘a triumphant dictation founded on political ignorance and lack of character and citizenship’.50 Ryan’s cheerful secularism in educational matters, the subversive and quizzical editorial tone, and his ridiculing of clerical opposition to mixed Gaelic League classes precipitated the paper’s suppression, in its first incarnation, at the hands of Cardinal Logue. The paper continued as the Peasant, now published in Dublin; from February 1907 it merged with Cathal O’Shannon’s Irish Nation and carried on under the dual name till December 1910. Bulmer Hobson was contributing feisty editorials by 1908, and the paper eventually absorbed Hobson’s own short-lived but influential journal, the Republic.51 Rosamond Jacob, on one of her forays into Dublin radical life from her Waterford base, visited the Peasant office in the summer of 1910 (‘awful looking’ on the outside) and was pleased to find Ryan ‘very affable in a melancholy way: he looks like a Russian anarchist, with very straight thick black hair and an ugly straight black beard.’52 By that date, Ryan had much to feel anarchical about. Other hard-line separatists saw him as more socialist than nationalist. The brisk young Ulster extremist Pat McCartan dismissed him as being ‘of the Gaelic League literary type; right enough of a kind but not the kind we want’.53

By 1910 Griffith too looked less and less like ‘the kind we want’. As Sinn Féin expanded and set the tone for political debate among radical nationalists from about 1905, advanced nationalists from IRB-dominated organizations began to try to make their own running. Accordingly, the awkwardly evolving relationship between Sinn Féin and the Dungannon clubs floated by Bulmer Hobson and Denis McCullough was reflected in the evolution of new journals. Griffith still retained kudos with young republican journalists as their ‘prickly but acknowledged guru’,54 but he was being outpaced. From 1906, when Griffith’s paper Sinn Féin succeeded the United Irishman, the tension between his idiosyncratic strategies of separation and classic Fenian verities became clearer. Bulmer Hobson, with his habitual optimism, cheerfully decided to enter the lists. In May 1906 Liam de Róiste heard that ‘Bulmer Hobson, of Belfast, intends bringing out a journal, to be called “The Republic”, to openly preach separation of Ireland from England, by Sinn Féin means’; the following December he recorded ‘sending a subscription, which I can ill afford, to Bulmer Hobson for the “Republic”, which is to be out this week’.55 Aided by Denis McCullough and McCullough’s father, a compositor who had worked on the Northern Weekly, Hobson featured sparky articles by Robert Lynd and others, including Hobson himself and his patron F. J. Bigger. ‘Think of me here in this respectable suburban residence,’ Bigger wrote dramatically to Alice Stopford Green from Ardrigh in January 1907, ‘writing such articles as that anti-militia one in last week’s R[epublic], and the anti-police one in this week’s and the anti-Belfast one in next week’s, and forsaking ’98 heroes – I must stop it or I am lost body and soul.’56

Hobson had raised £125 to start the paper, supplemented by 500 five-shilling shares.57 But he could never handle money (a failing bemoaned by McCullough, who conspicuously could), and the Republic did not pay its way; it had to be run down the following May, by which time Hobson had insouciantly decamped to Dublin, leaving McCullough ‘high and dry’. Hobson, unfazed, reprinted some of its key articles as pamphlets (including Lynd’s thoughtful analysis of the Orange Order), and ignored criticism from people such as Alice Stopford Green, who felt that his aggressive style had frightened off potential supporters.58 Griffith evidently decided to avoid this danger, while broadening his own readership. In August 1909 he started Sinn Féin as a daily paper, to appear along with the weekly version. In an attempt to reach an audience in provincial Ireland, the daily (four pages, costing a halfpenny) included literary criticism, fashion items and cartoons, as well as the standard fare of Gaelic columns and political character-assassinations. But it also meant taking a conciliatory line that would not frighten the rural petite bourgeoisie, as well as involving ingenious balancing-feats where funding was concerned.59 The ubiquitous Seán T. O’Kelly, Gaelic Leaguer and hopeful admirer of Mary Kate Ryan, was Secretary and Manager; it achieved a circulation of just over 3,000, when the weekly was selling 3,500. O’Kelly judged later that it was ‘doomed from birth’, though contributors included James Stephens, Séumas O’Kelly, Michael O’Rahilly, and Sydney and Grace Gifford.60 To true believers, Griffith’s attempt at reaching a wider audience inevitably meant dilution, and possibly corruption. P. S. O’Hegarty complained to George Gavan Duffy in September 1909 that ‘Griffith has watered down everything as low as he possibly can. In Thursday’s issue he proposes an alliance with the Tories! And the only definite idea in the paper seems to be to conciliate the unionists at all hazards. I believe in conciliating them but not at the expense of lowering our own practice or profession of nationalism.’61

To the separatist mind, Griffith was appearing more and more like the outdated but energetic old agrarian radical and Home Ruler William O’Brien, attempting to put together a feel-good coalition of moderate nationalists across a broad front, and in the process selling the pass as far as any real degree of independence was concerned. Attracting defectors from the IPP to Sinn Féin was not O’Hegarty’s idea of constructing a bridgehead into radical separatism. After six ambitious months the daily Sinn Féin ceased publication in January 1910. The response of Griffith’s IRB opponents was to start a new paper, Irish Freedom, which would ‘unambiguously reassert republican virtue’ – Bulmer Hobson’s Republic reborn.62

Controlled in succession (and partly financed) by McCartan, O’Hegarty, Hobson and – once more – MacDermott, Irish Freedom was the preserve of the Young Turks, and got off to a good start: 7,000 copies of the first issue were printed, and 6,000 of the second. By 1912 MacDermott could boast that its circulation was double that of Sinn Féin and An Claidheamh combined.63 IRB members were levied a shilling a month towards its support, making it a more or less official organ of the movement. Regular contributors included Pearse, Ernest Blythe, MacSwiney and O’Hegarty, while the business end was handled by Éamonn Ceannt, O’Rahilly and Béaslaí, with Cathal Brugha and Liam Mellows also involved. All would play a prominent part in 1916, and, unsurprisingly, the journal advocated unequivocal separatism and republicanism. O’Hegarty, writing as ‘Lucan’, added in religious toleration, free education, universal adult suffrage and equality before the law, though MacDermott editorialized that nationalism required the sacrifice of individual freedoms.64 The paper took an anti-Partitionist line early on, and by 1914 was effectively preaching armed insurrection. Cesca Trench was amused to hear the newsboys outside the Rotunda shouting, ‘Irish Freedom, Daily Mail, Daily Mail, Irish Freedom.’ She at first found it ‘frightfully rabid, it quotes bits from Indian papers about the English and urges all its young readers, “Fianna” it calls them, first to hate England, 2nd to love Ireland: a thoroughly bad principal [sic] I think!’65 But by 1914 she had decided it was

a really very striking paper sometimes . . . What strikes me most is the extreme youth of everyone concerned with it. Seán MacDiarmuid can’t be more than 25, with his cleanshaven boyish face and his dreamy blue eyes, and the others must be younger, from their looks. The way he writes, it’s all so young and honest and certain of himself and extreme, and yet every now and then there’s a suggestion that if England would do the decent thing an arrangement might be arrived at.66

This inference was a response to the fact that Home Rule had, finally, been passed into law, during tortuous negotiations at Westminster over the previous two years. Redmond had thus apparently regained the initiative, though the measure as passed was dismissed as inadequate by Irish Freedom and its readers, while Ulster’s resistance continued to block its implementation. It was, nonetheless, a critical juncture for separatists. Internecine strife soon broke out in the Irish Freedom office, highlighting a struggle between the older IRB generation, who were making a last push to regain control, and the young extremists (supported by Tom Clarke, middle aged though he was). This too was a key moment of inter-generational conflict. The future was with the young people, though when MacDermott was hospitalized with polio in late 1911, his opponents mounted what Piaras Béaslaí called ‘an amazing appalling rotten beastly filthy unheard-of disgusting inconceivable mysterious repulsive abominable’ attempt to kill the paper off.67 Béaslaí weighed in by delivering his own copy for the paper to Tom Clarke’s shop, in order to prevent its being spiked by enemies in the Irish Freedom office, and MacDermott eventually regained control. By now he and his mentor Clarke (to whom he was introduced by Hobson in 1907) were closely allied within the IRB. Though he had seen off the older Fenian generation, MacDermott would soon become more and more suspicious of his contemporaries Bulmer Hobson and P. S. O’Hegarty, thinking them not sufficiently extreme. This would be of decisive importance later, when the exhortations of the separatist press suddenly came within the bounds of reality. But in the pre-war era the freedom of the radical press from government censorship is striking. When drastic interference was inflicted upon independent-minded journals in Edwardian Ireland, it was far more likely to come from outraged senior Catholic clerics, who felt that their authority had been breached, than from the offices of Dublin Castle.

IV

By the same token, much of the driving power of the radical press was directed at the pretensions of other authorities besides the British state and the Irish Parliamentary Party. The tocsin to radical action against the older generation was also sounded by feminist and socialist journalism in the pre-war era. Bean na hÉireann, the voice of Inghinidhe na hÉireann, which was produced from November 1908 to February 1911 under Helena Molony’s editorship, advocated ‘militancy, separatism and feminism’. James Connolly and Bulmer Hobson wrote for it, as well as Constance Markievicz and Sydney Gifford. Arthur Griffith also contributed under a pen-name, declaring that Ireland was ready for ‘a gynocracy . . . I am weary living in a world ruled by men with mouse-hearts and monkey-brains and I want change.’68 The paper made room for socialist as well as feminist manifestoes. Suffragism presented more problematic issues: though consciously feminist, the idea of appealing to the British parliament for anything at all was anathema to several of Bean na hÉireann’s moving spirits. The editors and many of the contributors felt that national independence was the priority, putting their faith in a future, untainted, Sinn Féin government giving women the vote.

But they did not expect such a government to emerge peacefully. What is striking in Bean na hÉireann from as early as 1909 is the militancy of its pronouncements. Articles addressed ‘The Art of Street-Fighting’, and Helena Molony’s ruminations on ‘Physical Force’ in September–October 1909 can be read as a deliberate response to Griffith’s arguments in Sinn Féin that the militarist option was irrelevant, as it would simply be crushed by the might of the British Empire. In other articles too the need for bloodshed is discussed equably and even impatiently, and warm support expressed for revolutionaries in Egypt and India. Markievicz, much involved in her militaristic boy-scouting movement, issued a call to arms in the November 1909 issue. Her article ‘Women, Ideals and Nationalism’, originally a lecture delivered to the Students’ National Literary Society, left its audience in little doubt:

Arm yourselves with weapons to fight your nation’s cause. Arm your soul with noble and free ideas. Arm your minds with the histories and memories of your country and her martyrs, her language, and a knowledge of her arts and industries. And if in your day the call should come for your body to arm, do not shirk that either.69

While prioritizing the nationalist over the suffrage campaign, Markievicz’s contributions also condemned ‘the old idea that a woman can only serve her nation through her home’, and her own activism on several fronts bore this out. (So did the shambolic condition of her own household, mordantly noted by the bourgeoise Rosamond Jacob.)

After Bean na hÉireann ceased publication, Markievicz contributed to the Irish Citizen, established in 1912 as the journal of the Irish Women’s Franchise League – specifically feminist but also (especially under the guidance of Louie Bennett) a strong voice for trade-union rights. Socialist journalism was first represented by Connolly’s Workers’ Republic in 1898, published from the Abbey Street headquarters of his Irish Socialist Republican Party. Appearing irregularly, it was internationalist rather than nationalist, carrying syndicated articles from the left-wing press in Germany and Britain. The paper died around the time that Connolly left Ireland for a protracted sojourn in America. It would revive in 1915, with a different emphasis. A far more influential paper was the Irish Worker, edited by the controversial syndicalist Jim Larkin and contributed to by his sister Delia (founder of the Irish Women Workers’ Union in 1911 and the Irish Workers’ Dramatic Society a year later).70 Larkin started it in June 1911; he had earlier enjoyed a brief fling editing the Harp, which featured revolutionary socialistic manifestoes and libellous editorials. The Irish Worker cast a wider net. A weekly costing one penny, it sold very widely – just under 95,000 copies were in circulation within three months of its foundation.

The paper came into its own when recording the seismic effects of the 1913 Lockout, when Larkin’s Irish Transport and General Workers’ Union tried to challenge the employment practices of William Martin Murphy’s transport and commercial empire. The Irish Worker specialized in exposing the corruption and exploitation of bosses, preached a robust version of syndicalism, and implied separatist and republican politics, though both the Larkins would later be marginalized by the current of Irish nationalist politics, and their Irish political careers ended in disillusionment. Not long after its foundation, Rosamond Jacob decided that ‘the Irish Worker has changed from a fairly good Nationalist paper to a scurrilous rag full of abuse & personalities, no longer bothering itself to be patriotic.’71 But it attracted contributors such as AE, Standish O’Grady, James Stephens, W. P. Ryan and the playwright St John Ervine. In the years up to the Rising, the Irish Worker represented a forum for discussion of class, feminist and economic issues, often expressed with a Griffithite tone of withering irony; the Irish businesses specifically targeted (Jacob’s Biscuits, Gouldings Fertilizer, Thompsons’ Sweets, Pembroke Laundry, Keogh’s Sack Factory) added an equally Griffithite frisson of local reference and knockabout personal invective. But Larkin and his paper remained suspicious of Sinn Féin, which he judged to be consistently opposed to the interests of labour.

The Irish Citizen also started out as a weekly costing a penny, but its tone was more sober, which may be why it sold far fewer copies (3,000 per issue, whereas at its lowest the Irish Worker managed 20,000). Male suffragists such as James Cousins and Francis Sheehy-Skeffington were closely involved, as well as Hanna Sheehy-Skeffington and Louie Bennett, with the women eventually taking over more or less full control. Its primary objective, when founded in May 1912, was ‘to form a means of communication between Irish Suffrage Societies and their members’ and to publicize suffrage activities ‘untainted by party bias’, but the heightened political tempo of the next few years meant that national politics on other levels inevitably entered its pages. The editors’ determination to expose the misrepresentations offered by the mainline press also meant that it was bound to be combative and at times subversive.

This owed a good deal to the influence of Francis Sheehy-Skeffington, who exercised most of the control between 1913 and 1916. An Ulsterman who had cut his teeth on student journalism, he was never a friend to pietistic nationalism, and may have been responsible for the Citizen’s tactless and rather condescending mockery of the nationalist women’s organization Cumann na mBan (‘Association of Women’), established to support the (male) Irish Volunteers. The Irish Citizen referred to them, unforgivably, as ‘slave women’.72 It also campaigned against ‘the old idea of motherhood’, perhaps reflecting Hanna Sheehy-Skeffington’s impatience with domestic role-stereotyping. A superbly revisionist reviewer of the scandalous memoir by Katharine O’Shea, widow of Charles Stewart Parnell, analysed Parnell’s fate as ‘the Nemesis of the anti-feminist . . . to fall victim to a woman of the highly-sexed, unintellectual type, developed by the restriction of women’s activities to the sphere euphemistically styled “the Home” ’.73 This could have been written by either of the Sheehy-Skeffingtons, and accurately reflected their iconoclastic approach to domestic pieties.

The suffrage issue challenged other boundaries too. Much space was devoted to the debate between militant and peaceful suffrage tactics, some of the contributions suggesting a distinctly radical notion of the position of women in contemporary society, and a strong sense that the advanced position of the Pankhurst sisters could profitably be adopted in Ireland. There was a distinct aura of threat: ‘What Will She Do with It?’ asked one cartoon depicting a suffragette, armed with the vote, looking contemplatively at a hand grenade and a flask of paraffin. Though the relationship of suffragism to advanced nationalism is a tangled pattern, there is certainly evidence that the advocacy of rebelliousness, the desirability of imprisonment in a martyred cause, contempt for members of the Irish Parliamentary Party and the duty of assailing the representatives of British rule in public translated easily from the suffrage cause to the cause of Ireland. And this was not affected by the actual passing of a Home Rule Bill in 1912–14, complicated as it was by Ulster’s resistance and the opposition of the House of Lords. The stance taken by the radical press, at all levels, had long presented the Home Rulers at Westminster as a rhetorical irrelevance, and the terms of the Bill as falling far short of meaningful independence (particular scorn was directed at the continuing presence of Irish MPs in the imperial parliament, and that body’s retention of power over taxation and land-purchase arrangements). The militarization of Irish society, as will be seen in the next chapter, accentuated this reaction. For the readers of advanced papers, another political reality existed beyond the world of political negotiations in London, and the machinations of the Ancient Order of Hibernians at home.

With the outbreak of war in 1914, the stance of the Citizen implied a further degree of subversion. Many of those associated with it were pacifists. However, other elements, especially suffrage societies with large unionist memberships, threw their energies into the war effort. There was also the underlying argument – as in Britain – that enacting the role of full citizens would qualify them for the vote when hostilities were over, but several Irish radicals saw through this wishful thinking. The suffragist and trade-union organizer Louie Bennett wrote despairingly to Hanna Sheehy-Skeffington that their pro-war colleagues were ‘like sheep astray and I suppose when the necessity of knitting socks is over – the order will be – bear sons. And those of us who can’t will feel we had better get out of the way as quickly as we can.’74 Depressingly for people who felt like that, the majority of suffragists probably supported the Allied cause. Nonetheless the debates in the columns of the Irish Citizen continued to question the war effort, and to argue the possibilities for female enfranchisement in the aftermath of the juggernaut.

The outbreak of war provided new opportunities for subversion, and heralded a new era, to be discussed in the next chapter. But its effect on the world of publishing and printing should be noted here. The publishing of anti-recruitment posters and pamphlets boomed, many of them printed on Constance Markievicz’s private press. She told Cesca Trench that they were all the more effective when composed by one of her Fianna scouts: ‘you see, to appeal to a certain class of people, the ones we want to prevent enlisting, you must get one of their own class to write for them, they know.’75 Above all, those who had been practising radical journalism for the past fifteen years or so threw themselves into the so-called ‘mosquito press’, producing gadfly anti-war and pro-separatist propaganda sheets which danced around the censor.

Thus the coming of war projected the activities of subversive journalists into a whole new realm. But the radicals had already received an education in political organization and rhetorical invective through the explosion of journalism originating at the turn of the century. This phenomenon had also done lasting damage to the image of the constitutional nationalists of the Irish Parliamentary Party. The blizzard of news-sheets wrote the revolution into the hearts and minds of young radicals far more potently than the poems of Yeats or the fictions of George Moore. It also flourished in the conditions of repressive tolerance which characterized Edwardian Ireland, and ended with the coming of the world war.

And that war brought other implications too, grasped at once by some of the revolutionary generation. Long afterwards, in a vivid unpublished memoir, Gearóid O’Sullivan remembered a Dublin afternoon stroll in late June 1914 with a republican friend.

That afternoon I was walking up past the Black Church with Seán MacDermott when a newsboy shouted at the top of his voice, stop press!!! Stop press. I paid a penny for a copy of the ‘Pink’ as the Evening Telegraph was familiarly known. The ordinary price was a halfpenny.

Having read the stop press news I was asked by Seán what it was all about. ‘Nothing’, said I, ‘only some old Duke shot in the Balkans.’ ‘Give me that,’ said Seán excitedly. As he read the few lines his piercing eyes seemed to dart from their sockets. Holding the paper in his left hand, staring at me intently, he smacked the back of the paper with the back of his upturned right hand (this was a usual method of emphasis with him) and addressed me: ‘Look it, Gearóid, this is no joke for us. We’re in for it now. Austria will move against these fellows’ (I didn’t know who ‘these fellows’ were), ‘Russia will back these fellows up, Germany and Italy will back Austria, France will take on Germany. You’ll have a European war; England will join – and that will be our time to strike.

‘I must go back. See you tonight’, and he left me.76

Thus we come back, ‘by a commodious vicus of recirculation’, to James Joyce’s windy breath of Aeolus. It seems only apposite that the revelation of the long-awaited apocalypse came, like so much else in the era, through the cry of a newsboy in a Dublin street.