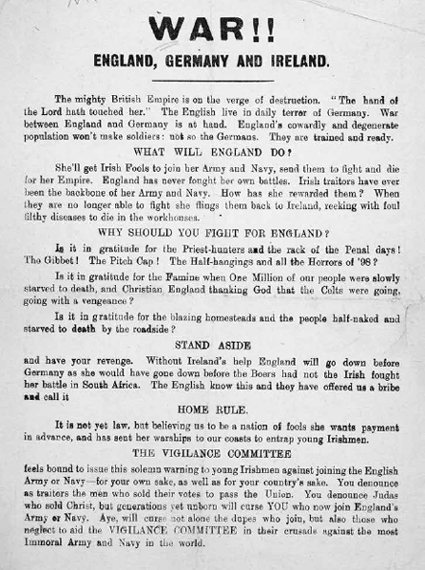

The political and historical reasons against Irishmen joining the Allied war effort, as spelt out in an anti-recruitment flyer, 1914.

Is it only half fun? Or children playing battle. Whole earnest. How can people aim guns at each other. Sometimes they go off. Poor kids.

– James Joyce, Ulysses1

I

As he looks out over Dublin Bay on the evening of 16 June 1904, Leopold Bloom is musing about children’s lives, not contemporary politics. But Joyce wrote the ‘Nausicaa’ section of his panoramic book in the aftermath of the Easter Rising, and the reflections on violence studded through Bloom’s soliloquies must be read in this light. By early 1914, ‘aiming guns at each other’ had become a way of life in Ireland, with about 250,000 men (and quite a few women) in Ireland enrolled in some kind of paramilitary organization. These forces, which sprang up like dragons’ teeth, drilled and armed openly, with an extraordinary degree of connivance from the authorities. It was only when hostilities broke out in Europe in August 1914 that some selective efforts were made to control – and redirect – the militarization of Irish society. But it was also the outbreak of war – as Seán MacDermott saw from that Dublin newsstand – that presented the IRB with its traditional opportunity for an insurrection. Nonetheless the IRB comprised a very small number of people; and ‘outside the IRB there were few Republicans, and Griffith knew it and so did we’, as Patrick McCartan recalled later.2 It is unlikely that armed rebellion would have come, at least in the form it did, without the spectacular commitment to military posturing, and the cult of guns which characterized radical Irish circles from 1912.

Violence, so long part of the rhetoric of ‘advanced nationalism’, became translated into reality. This built on many of the attitudes, antagonisms and alliances already established among the revolutionary generation. But it was also projected into actuality through the surge of paramilitary activity that began in Ulster during 1912, registering opposition to the prospect of the Home Rule Bill, and the opposing movement which developed among nationalists. This readiness to take arms reflected the long-standing Irish exposure to the reality of militarism, as well as to its rhetoric: the army was an established presence in barracks and ‘garrison towns’, and Irish soldiers were prominently distributed through that army, at every level. The implicitly intimidatory presence of barracks, and the high number of Irish recruits into the British Army (notably from the urban working class, but also from rural areas), provided a consistent target for Sinn Féin rhetoric; the high profile given to this issue indicates the prominent role the army occupied in Irish life, as employer as well as symbol. Anti-recruiting activities, from the Boer War onwards, provided an important forum for displaying nationalist probity, and would become a focus of subversive activity from August 1914. Liam de Róiste’s complex feelings about having two brothers as British soldiers were confided to his diary: ‘they have always been cut off from me.’3 Liam Mellows, and some other future revolutionaries, grew up in an army family; some, including James Connolly, Michael Mallin and Tom Barry, actually served in the army themselves. In Irish life, the position occupied by the Royal Irish Constabulary was also prominent, similarly providing a target for nationalist opprobrium, since they were armed and, to a certain extent, paramilitary, though in a ceremonial rather than an activist way. ‘The police were more military and the military more police-like than in Britain’;4 the relationship between them was correspondingly complex and uneasy.

The antagonism expressed by advanced nationalists towards the militarist forces of law and order did not prevent separatists enthusiastically following their example. With the exception of rare pacifists such as Francis and Hanna Sheehy-Skeffington, radical nationalists warmly endorsed the idea of possessing guns, taking part in drilling and other exercises, and theoretically preparing to ‘strike a blow for freedom’. For many of the revolutionary generation, the idea of arming had become central to their self-image as Irish nationalists well before the acquisition of arms in 1913–14. The language of ‘striking a blow for Ireland’ was a well-worn trope. But some of them, like Liam de Róiste, had already begun uneasily considering the logical next step. In one of the frequent moments of self-doubt recorded in his diary during 1903, he wondered if all his efforts in little Cork societies, striving for political and cultural independence, were worth it. ‘It is evident that as long as England is in the ascendant, we shall have to fight for freedom. How can we fight? It becomes more and more difficult with the complexity of life.’ A few months later he was sanguine again:

Perhaps our independence cannot be rescued without war. Well, we must only face the armed struggle as former generations of Irishmen faced it. If it can be attained without a physical conflict, it would be a blessing. The attainment of our independence will mean a revolution. Many people fear when they hear that word. They attach some terrible and sinister meaning to it. Revolutions are taking place frequently. They do not appear such desperate things as some imagine.5

By January 1906 he was reconsidering what fighting actually meant, in the wake of a violent affray at a Kerry election meeting. ‘It makes me tremble. Blood! Heads battered in; oaths and curses; malignant hatred displayed; innocent and unoffending persons harmed and injured; passions let loose. And in the ultimate, all for what?’ The uncomfortable thought occurred that this kind of thing was exactly what his political involvement might one day entail: ‘Mayhap war itself, with sickening sights, and possible carnage; burnings and destruction? For Ireland? And what is Ireland? This sod of turf beneath my feet; these people around me? The sod is clay, as clay in any part of the world might be. The people around, as people in general anywhere, would shout one up today and howl one down tomorrow.’ As usual, rhetorical questions enabled an evasion of awkward answers. But de Róiste also reflected that some of his companions believed that any ‘freedom’ not attained by physical force was invalid. ‘To them “physical force” is a creed and an object in itself.’6

Nonetheless, before the crisis of 1912, how far a militarist organization actually implied violence was a moot point. As early as 1902 Bulmer Hobson tried to organize a nationalist boy-scouting movement, revived as Fianna Éireann in 1909, with Constance Markievicz on board; this echoed not only Baden-Powell’s celebrated movement, but also religion-based youth-groups which employed military models and rhetoric. In September 1912, as the crisis over the Home Rule Bill escalated, a Young Citizen Volunteers movement was founded in Belfast, intended to develop patriotic values through ‘modified military and political drill’, and aimed at young men rather than at boys. While declaring itself non-sectarian and non-political, this initiative coincided with the signing of the Ulster Covenant and seems to have been the forerunner of the great wave of volunteering put in motion by the Ulster Unionist Council four months later, which founded the Ulster Volunteer Force, or UVF.

Building on widely diffused organizational initiatives centred on Orange Order halls across the province, the Ulster Volunteer Force came into being in January 1913, declaring its intention to prevent the implementation of the Home Rule Bill by force. Mobilizing a third of the male Protestant population of the province, it was rapidly backed by an influential array of prominent retired military men, and covertly supported by many serving officers within the army. Their leader was Edward Carson, a lantern-jawed Irish lawyer and Conservative politician with a fearsome legal reputation and a powerful platform presence; despite his Dublin background and metropolitan career, he rapidly became the symbol of Protestant Ulster’s resistance to the perceived tyranny of the nationalist majority. The Ulster Volunteer Force drilled, created enormous public demonstrations and, most importantly of all, imported arms in large numbers. And no matter how extreme their declarations of intent to fight against the policy of the elected Liberal government, that government decided not to proceed against them in any way.

This supine acquiescence was not the least of the factors which encouraged nationalists to follow suit. The tiny Irish Citizen Army, organized by radical trade unionists during the Dublin lockout of 1913, invoked the example of the Ulstermen, as did a couple of autonomous militias attached to the Ancient Order of Hibernians. The Citizen Army also reflected the increased tempo of labour unrest in Dublin at this time; between February and August 1913 there were thirty major labour disputes in Dublin. These mostly involved the ITGWU. Connolly’s tiny Irish Socialist Republican Party, founded in 1903, amalgamated with the Socialist Labour Party as the Socialist Party of Ireland in 1904, but maintained a rather sketchy existence. It was effectively relaunched in 1909 at a meeting convened by the labour leader William O’Brien. This called for independent labour representation on elected bodies, support for the national language and the democratic advance of socialism within Ireland; a separatist agenda was not formally in evidence. The great labour crisis of 1913 mobilized many of the Dublin proletariat, as well as some middle-class supporters; though the Citizen Army never numbered more than a few hundred, and was founded as a civic defence organization, it employed aggressively militarist language. After a period of demoralization and inefficiency following the collapse of the lockout, and with James Larkin’s departure to America on a fundraising tour in October 1914, the Citizen Army became James Connolly’s organization, supported by Michael Mallin as Chief-of-Staff. Mallin was one of several ICA members with British Army training, and from 1915 the ICA would practise drilling, mock street-fighting and the taking of buildings. With the outbreak of war, Connolly decided it would act as a revolutionary vanguard force.

But the most influential reaction to Ulster’s example came in November 1913 with the formation of Óglaigh na hÉireann, the Irish Volunteers. The original inspiration was declared in the journal of the Gaelic League, An Claidheamh Soluis, in an article by the academic historian Eoin MacNeill; the more militarist figure of Michael O’Rahilly was also involved in the initiative, as was their Gaelic League colleague Patrick Pearse. This was the military organization that so many of the revolutionary generation had been waiting for. And, though the Irish Volunteers’ declared raison d’être was the defence of the Home Rule Bill now proceeding towards enactment, many of its moving spirits had a more proactive agenda in mind. This was borne out by the membership of the organizing committee of the new movement, which was rapidly commandeered by influential members of the IRB.

Thus subversion happened in public, through the formation of groups such as the Fianna, the Citizen Army, the Ulster Volunteer Force and the Irish Volunteers. It is nonetheless striking how many people in this era in Ireland put their faith in possessing arms, while not actually facing up to the consequences. In this, they reflected an emotion widely shared across contemporary Europe. In the military boy-scouts movement started by Bulmer Hobson and Constance Markievicz, the longing for guns figured large, though they often had to be replaced by hurley-sticks. Backed by the kind of militaristic drill afforded by Con Colbert at St Enda’s, this training could be very effective; there was much concentration on ‘scouting’ and ‘first-aid’ techniques. More crudely, they could also practise street-fighting and vigilante activities, as in ambushing marches of the Protestant Boys’ Brigade. And eventually, as one ex-Fianna scout recalled, there was the possession of ‘a real gun . . . a great sensation’. Sometimes these came from surprising sources, as recalled by another old Fianna member. His branch got their much envied .22 rifles from Father Paddy Flanagan, the parish priest in Ringsend. ‘He was not the ordinary type of popular curate,’ this witness coyly added. ‘Would it be indiscreet to mention that he was the inventor of the sawn-off shotgun?’7 He was not, but the admiring assertion of such a claim is in itself significant.

Memoirs such as Seán Prendergast’s, compiled for the Bureau of Miltary History, vividly illustrate the way in which membership of the Fianna acted as a conduit into the Volunteers movement and the Citizen Army, and actively prepared for militarism.8 Prendergast, who joined up in 1911, found himself learning military drill, first-aid, signalling, scouting, map-reading and even shorthand (this last from a clerk working in the Land Commission). The boys’ uniform, initially featuring Boer-inspired slouch hats and blouses, was redesigned to incorporate military tunics with epaulettes, thanks to a captain who worked as a clerk in Clery’s drapery department, and a Mounties-style hat; the adults who trained them, like Liam Mellows, often appeared in kilts. Urban working-class boys found their weekends transformed by route marches and mock battles in the Dublin suburbs, or camp-outs at Countess Markievicz’s cottage at Balally in the Dublin Mountains. Her Rathmines home, Surrey House on Leinster Road, was also open to them, representing an escape from the confines of home, where they could observe the radical bon ton at play (even though ‘Madame’s’ easygoing habits and constant smoking shocked some). If they failed to turn up through illness, the Countess was liable to appear at their homes and carry them back to convalesce in the untrammelled surroundings of Surrey House, over the protests of their mothers.

Above all, young as they were, they had access to arms. Prendergast’s company first obtained French bayonets in April 1913. ‘Strange how the minds of young rebels work! Even at this stage many of us were thinking of becoming armed. Some did.’ A few revolvers were subsequently legally obtained on hire purchase, and in late 1914 their captain, Seán Heuston, managed to procure .22 Springfield rifles from America. The Fianna were also closely involved in disseminating the IRB journal Irish Freedom, in which Pearse’s articles declaring the necessity of bearing arms for Irish ‘virility’ were beginning to appear.

II

Up to 1912–13, however, Irish nationalists older than the Fianna membership were not drilled into any kind of armed formation. Nonetheless the felt need was there. In October 1912 a fellow member of the Waterford Gaelic League surprised Rosamond Jacob by his ‘whole-heartedness’. ‘He believes in physical force and says there should be rifle clubs and that another opportunity like the Boer War should not be let pass . . . he says he knows a lot of men – married men some of them – up and down the country who take no interest in constitutional politics, but would be ready to come out with a gun.’9

After the foundation of the Irish Volunteers a year later, nationalist drilling and paramilitary organization happened with extraordinary speed, first by means of cover organizations, then in the open under the eyes of the authorities, who appeared either helpless or conniving or both. The movement got off to a flying start, with 4,000 volunteers joining up after a public meeting in November 1913, stewarded – inevitably – by the Fianna; it met a felt need for militant nationalism. One reason for this was the idea that the bearing of arms somehow qualified a people for nationhood: an armed citizenry. This was one more historical echo from the Late eighteenth century in Ireland, picking up resonances from the Dungannon clubs, the Wolfe Tone societies, the cult of Robert Emmet and all the rest. It was remembered that the freedoms wrested from the British government in 1782, leading to a more autonomous Irish parliament, had come after militias called ‘Volunteers’ had been set up all over Ireland, threatening contagion from the recent American revolution. When an Irish national volunteering movement emerged in 1913, ostensibly to protect the recently passed Home Rule Act from being stymied by Ulster resistance, much was made of the historical parallel – though the more recent inspiration was in the north-east. The account of a Volunteers drill party which Eimar O’Duffy put into his autobiographical novel The Wasted Island makes this historical connection clear.

Shortly before nine Crowley got out his motor and they drove over to the meeting-place, the field of a friendly farmer some five miles away. About twenty men were already assembled when they arrived, and half a dozen more straggled in during the next quarter of an hour. Under the cold light of the moon Bernard drilled them: a weird and romantic experience. Upon how many such assemblies had that disc looked down through the long history of Ireland’s passion? Fenians, Confederates, United Irishmen, all had drilled and marched in turn under her gentle light. She had watched the tide of hope and despair generation after generation, and was still watching – for what? The ghosts of Ninety-Eight and Forty-Eight and Sixty-Seven seemed to be abroad that night.

In the shadow of a hedge a policeman stood taking notes.10

O’Duffy himself played a central role in the administration of the Volunteers. As well as contributing a good deal to the organization’s strategic thinking, he wrote much of the journal Irish Volunteer. Like other Volunteer officers such as Terence MacSwiney and ‘Ginger’ O’Connell, he wore his uniform on every possible occasion. Tutored by their mentor Bulmer Hobson, O’Connell and O’Duffy spent much time theorizing about guerrilla warfare (‘hedge-fighting’); some of their IRB colleagues within the Volunteers were more inclined to open insurrectionism, a rift which would become clear in 1916.

Formally, however, the declared object of the Irish Volunteers was to protect the recently passed Home Rule Bill for Ireland, with the eventual aim of becoming ‘a prominent element in the national life under a National government’. In other words, the Volunteers were to be an independent Irish army in waiting. But this presupposed the safe achievement of undiluted Home Rule: and, despite the passing of the Bill, the removal of the powers of the House of Lords (which had thrown out a Bill passed in 1893) by the 1911 Parliament Act, and the apparent victory for John Redmond and constitutional Home Rule, this seemed an increasingly remote possibility after 1912. The Irish Parliamentary Party at Westminster had brought off a technical victory, placing the capstone on the edifice begun by Parnell when he forced Home Rule on to the Liberal Party’s agenda with the unsuccessful Bill of 1886. But a heavy shadow lay across it. Ulster’s resistance, and the enthusiastic support offered it by the Conservative Party, required complicated and dedicated negotiations behind the scenes by Redmond and his lieutenants; at first devoted to keeping the Liberal government firm on the issue, discussions soon revolved around the hardening inevitability of negotiating some kind of separate arrangement for Ulster, a concept edging into more general acceptance. The kind of compromise which in retrospect seems inevitable was, however, scornfully derided by advanced-nationalist opinion – though a majority of them would tacitly accept such an arrangement a few eventful years later. In 1914, what Redmond and the Irish Parliamentary Party had achieved seemed to radical imaginations in Ireland an inadequate structure, flimsily assembled and founded on sand.

This was not only a result of the Ulster crisis. The complex of generational attitudes and subversive activities fructifying since the turn of the century had helped to create a situation where Redmond’s Irish Parliamentary Party seemed more and more old-hat, collaborationist and unexciting. It was found wanting on all the issues that inspired the revolutionary generation (Irish language, cultural renewal, economic autarky, separatist traditions, the eradication of ‘foreign’ influence). The formula of Home Rule within the Empire seemed insufficient to many of the younger generation, who were not enthused by the pragmatic argument that it was a vital first step towards a more full-scale detachment, to be achieved by a series of non-violent initiatives. Above all, the credibility of the Home Rule solution was seriously undermined by the scale of resistance among Ulster unionists, and by the British government’s pusillanimous response to that challenge. As Liam Ó Briain pithily put it to Seán T. O’Kelly, ‘our military movement only became feasible thanks to Edward Carson.’11

The same case is powerfully argued by the unpublished memoir of the Trinity student Kevin O’Shiel. As Asquith and his colleagues backed down before unconstitutional challenges from unionists, O’Shiel’s belief that a Liberal government would keep faith with the democratic mandate for Home Rule crumbled. A crystallizing moment occurred in March 1914, when a group of British Army officers stationed at the Curragh declared they would resign rather than obey an order to put down Ulster’s resistance to Home Rule; after some confused negotiations and a couple of resignations, the so-called mutineers were reinstated. The prospects for implementing Home Rule in an unpartitioned Ireland seemed increasingly doubtful. This may account for the lack of enthusiasm which greeted the passing of the Bill, much noted by police observers at the time.12 Those with socialist and secularist leanings, like Francis Sheehy-Skeffington, had further worries, as Rosamond Jacob recorded in March 1913 when she called at Belgrave Road. She found him disillusioned with the Citizen Army, and the general drift to militarism. ‘He expects rough times if Home Rule materializes, fighting clerical and capitalist influences; says we shall probably all be executed or banished and that if Home Rule doesn’t materialize there will be a rebellion against the Party’ – which he would incite himself if he had to. After suffrage was won, Sheehy-Skeffington concluded, the first battle must be against the priests – a prophecy which Jacob received with predictable pleasure.13 But these issues faded further into the future, as older lines of antagonism were drawn up.

As Dublin radicals debated, voluntarist militias continued to mushroom in the north-east under the umbrella of the Ulster Volunteer Force, pledged (by covenant) to fight against the government in order to stay in the union. Under the charismatic leadership of Edward Carson, their movement increasingly displayed the trappings of threatened rebellion. In the South, IRB infiltration of the Irish Volunteers continued apace. Within the Citizen Army organized by James Connolly too a separatist element was conspiring; and it is striking how few old Citizen Army recruits, recalling their enlistment much later when testifying to the Bureau of Military History, ever mention being motivated by class solidarity. Nationalism trumped socialism, at least in their memories, and very probably at the time as well.

The career of Michael Mallin is enlightening. Born in 1874 in the Liberties of Dublin to a carpenter and his silk-worker wife, he followed a family tradition by joining the British Army in 1889 and served in the Royal Scots Fusiliers, spending six years in India. In 1894, home on leave, he met Agnes Hickey, from a Fenian family in Chapelizod; their correspondence indicates his increasing radicalization during his time in India, as well as a fervent Catholicism.14 He returned to Ireland in 1902, and they married the next year. After trying many jobs, Mallin became a silk-weaver (the Irish poplin industry was undergoing a revival) and by 1908 was prominent in the trade union. He emerged as a strike leader during 1913 and subsequently started his own shop, which folded. There were stabs at other ways of making a living (chicken-farming in Finglas, a cinema venture in Capel Street, piece-work weaving at home), but he was also forced to consider emigration. Then, in October 1914, after Larkin’s departure and Connolly’s ascendancy, he became an important figure in the ITGWU. Despite rows with his own union, thanks to Connolly’s patronage he succeeded his friend William Partridge as manager of the Emmet Hall, Inchicore. Labour and nationalist radicalization went together for Mallin. At first unwelcome in Fianna circles, he had started his own nationalist scouting group, and soon rose through the ranks of the Citizen Army; he also at this time began to acquire guns from hard-up soldiers at the nearby Richmond Barracks. He would follow Connolly into the paths of nationalist revolution a year or so later.

The mainstream nationalist militia followed a more chequered ideological course. The Gaelic Leaguers in the office of An Claidheamh Soluis, who originated the idea of the Irish Volunteers, soon found themselves in a complicated position. Though MacNeill’s article ‘The North Began’ started the ball rolling, credit for inspiring the nationalist Volunteers was also claimed by Michael O’Rahilly. The rich son of a Kerry shopkeeping dynasty, he lived a dilettante life in Dublin and had (as seen in the last chapter) found his niche as business manager of the Gaelic League magazine An Claidheamh Soluis.15 After travels in the USA, a large private income allowed him to develop strident and uncompromising ideas about the necessity for language revival and separatist activism, as well as a deep dislike of Britain and Britishness, loudly expressed. He built a holiday bungalow at Ventry, County Kerry, where he became close to Ernest Blythe and Desmond FitzGerald, who had temporarily settled in the area to perfect their Irish-language skills and mobilize the rather refractory local population. The Volunteering movement also gave full rein to O’Rahilly’s obsession with heraldry, titles and coats of arms; his papers include much semi-mystical correspondence about the spiritual symbols of the Volunteers flag and the need to evoke occult Celtic harmonies.16 More relevantly, he was also mesmerized by the ways in which new technologies such as motor-cars and aeroplanes could be used for warlike purposes. O’Rahilly, whose Anglophobia had been nurtured by a sojourn in America, represented an extreme and violent tendency within the movement. In his view the eventual destiny of the armed citizenry was to strike a blow for freedom against British government, and in this he was not alone.

Other early enthusiasts such as Roger Casement emphasized that the organization’s proper name must be the ‘Irish Volunteers’, avoiding the words ‘national’ or ‘nationalist’: sectionalism must be guarded against, and patriotism seen to outweigh politics. This was often exposed as an unrealistic ideal, but the organization of the Volunteers was clearly influenced by the idea of a citizen militia. Officers were elected rather than appointed, brigade and battalion structures varied, and the leadership resembled a political committee rather than a military high command. As so often in Irish history, uncertainty of nomenclature indicated an amorphous and unstable nature. Separatists like O’Rahilly and Casement unwillingly realized that the movement also enthused loyal Home Rulers such as Tom Kettle; worse still, by the summer of 1914, John Redmond and the Irish Parliamentary Party involved themselves formally with the direction of the Volunteers, in what seemed to be an effective takeover of the public face of the movement. Local politicians began to dominate committees at ground level, and the influence of Joseph Devlin’s confraternity, the Ancient Order of Hibernians (deeply hated by Sinn Féin and the IRB for its conservatism and aggressively pious Catholicism), made itself felt. (Astutely using its status as a ‘friendly society’, the AOH had enormously strengthened its influence through monopolizing the organization of workers’ insurance through the recent National Insurance Act of 1911.) In May the AOH branches were ordered to form their own Volunteer companies; there were already a large number of their members in the Volunteer ranks, along with those who had come in from the more radical breeding-grounds of the Gaelic League, Sinn Féin, the Citizen Army and the IRB. As they captured the national imagination, the Volunteers came to resemble a broad church.

One result was an explosion of numbers. Local studies show that the movement spread like wildfire, often endorsed by unlikely local notables, though these establishment figures tended to fall away as the Volunteers became more stridently nationalist.17 From a force of about 20,000 in March 1914, the movement grew to 150,000 by the following July, and the profile of its membership became accordingly more moderate, including a fair number of Protestants with British Army backgrounds. Even more repellent to radical nationalists was the ramifying influence of the Hibernians, an organization whose root-system proliferated all over Ulster, and which was seen by many as a worse enemy than the Saxon oppressor. Connolly, for instance, thought that the bigotry and politicking of the Hibernians were what kept the Orange Order artificially alive: ‘to Brother Devlin, not to Brother Carson, is mainly due the progress of the Covenanting movement in Ulster.’18 Seán T. O’Kelly remembered the AOH as Sinn Féin’s real adversary in the pre-Rising years: ‘the bitterest enemies we of the independence movement had to fight’, organizing thugs who threw lime and beat them ‘black and blue’ at election meetings.19 Hobson and his Dungannon Club companions had long seen Devlin and his associates as a real threat to nationalist revival, referring to them as ‘Ribbonmen’, with all the attendant implications of archaism and confessionalism. Ironically, when Hobson and Denis McCullough had initially recruited Seán MacDermott, they had been worried by his AOH, or ‘Mollie’, tendencies, which they were determined to eradicate. ‘He was an extremely religious man at the time,’ McCullough later recalled, ‘but we cured him of that.’20

The hatred of the radicals for the Hibernians helps to explain the fury of some of the IRB cabal within the Volunteers at seeing Redmondites apparently take over their movement from the summer of 1914: it betokened the importation of all the old clientilist and collaborationist values which they abhorred. Since the turn of the century it had been an article of faith for Sinn Féiners and other radical nationalists that Redmond and his party represented all that was ineffectual and corrupt about parliamentary nationalism, demonstrated time and again in their trimming approach to issues such as local government, compulsory Irish in the National University, and finally the dilution and postponement of Home Rule. The Volunteering movement had sprung up, it was felt, in manly opposition to the supine values and attitudes of Redmond and his followers. Yet, in June, Redmond succeeded in getting a guaranteed majority of his nominees on to the Provisional Committee. Accordingly, this unexpected turn of events produced a lasting and antagonistic split within the IRB. The agonies of those who accepted this are vividly expressed in a dramatic letter from Casement to McCartan, beginning ‘Last night we committed Hara Kiri!’ Casement nonetheless went on to defend the capitulation as ‘an act of larger patriotism – not of small surrender’, essential in order to preserve unity among the Volunteers, and to avoid the charge of deliberately wrecking Home Rule. ‘But the real “principle” to stick to – is get rifles,’ he added. ‘If the Party are sincere & not public liars they will help us to get rifles.’

They were to do this by pressurizing the government to withdraw ‘the insulting & outrageous arms proclamation aimed at a White race & designed to reduce our citizenship of this so-called United Kingdom to that of a servile coloured population. Don’t say all this at your meeting but say it privately.’ Casement, near the end of his tether, went on to plead his case, as someone who had given up ‘a post of the highest honour & profit’ and reduced himself to ‘paupery’ for the cause:

I broke my career & surrendered everything – ease, comfort, wealth – when in broken and failing health too – in order to try & help Ireland to freedom. I mean to get guns into Ireland – & you can say so if you like . . . The young men with the rifles will make the new Ireland – once they get them they will not lay them down save with their lives.21

Others who endorsed the strategy of incorporating Redmondites into the Volunteers command included MacNeill, O’Hegarty and Hobson. As MacNeill admitted:

A clear majority of the 25 [on the Committee], including the four clergymen, are A.O.H. men. Nevertheless the Volunteer idea & the Volunteer principles & programme will come out on top. There are a number of decent Irishmen among the 25, a number of unshaped men, & a number of wasters. The Volunteer idea will capture all but the last lot. As the men get armed by degrees, the whole situation & its possibilities will be transformed, and a new standard – or an old one – will be set up. As a friend of mine quotes, ‘There was a young lady of Niger, Who went for a ride on a tiger, They returned from that ride with the lady inside, and a smile on the face of the tiger’.22

This suggests that, in MacNeill’s view, the Volunteers were to be groomed for more aggressive purposes than defending Redmond’s achievement. Hobson defended the decision all his life, taking credit for the responsibility and describing it later as ‘one of the wisest & most misunderstood of my actions . . . we never lost grip. I even appointed the office staff at headquarters while there was a Redmondite majority on the Committee.’23

But hardline IRB men were not convinced, and a lasting rift was created, separating MacNeill, Casement, Hobson and P. S. O’Hegarty (who thought this new access of membership could be used to advantage) from their more irreconcilable colleagues. Seán MacDermott was particularly irate, denouncing Casement and Hobson as sell-outs, and Tom Clarke wrote bitterly to Joseph McGarrity describing the betrayal of the Volunteers by Casement’s ‘master hand’, with Hobson as his ‘Man Friday’.24 This enduring animosity, Redmond’s apparent achievement of dominance and the eventual absorption of the moderate elements of the Volunteers into the war effort have tended to conceal the radical-separatist element there from the beginning. And, though MacNeill and even Casement appeared more moderate, their correspondence shows that a long-term militant strategy lay behind their actions. It might also be remembered that MacNeill’s nominated liaison committee for the Irish Volunteers in December 1913 included, besides O’Rahilly, Éamonn Ceannt, Joseph Plunkett, Thomas MacDonagh, Patrick Pearse and Seán MacDermott. All were future signatories of the ‘Proclamation of the Irish Republic’ at Easter 1916.25

III

The strategies of such people went underground after Redmond’s takeover in the summer of 1914, while the social range and political variety of Volunteer members increased noticeably. The public rhetoric of Volunteering favoured protecting ‘the rights and liberties common to all the people of Ireland’; as Matthew Kelly has demonstrated, the language among the National Volunteers stressed a defensive role, linking ‘manliness’ with ‘arms-bearing’ in a clear reference to the language of civic rather than revolutionary republicanism, which looked back to the rhetoric of the American War of Independence. MacNeill, himself a Northern Catholic, saw the movement as not only a response to the armed citizenry of Ulster, but also the possible beginnings of a rapprochement with the Northern brethren. From a later vantage, this seems puzzling; the logic of having one militia in the North, pledged to fight against Home Rule, and another in the South, pledged to fight on behalf of it, seems to be that they should end by fighting each other. This was what was in the mind of police inspectors when they repeatedly warned their political masters in 1914 that Ireland was on the brink of civil war.

For nationalist ideologues, however, it was more comforting to go back – yet again – to history, and specifically to the historical moment in 1798 when Catholics and Protestants allegedly came together in the interests of Irish independence. The use of this memory in Ulster was particularly complex, involving the traditions of Presbyterian radicalism, which had later mutated into hard-line unionism in the early nineteenth century. But for Protestant nationalists like Bulmer Hobson, Alice Milligan, F. J. Bigger and Roger Casement, Wolfe Tone’s oath sworn on Cave Hill with his Ulster companions was a sacred memory, much invoked in the 1898 centenary and now revived in the militias of 1913–14. By the same token, Rosamond Jacob was obsessed by memorabilia of that golden moment: devoting much time to researching Tone’s life, and sending away for relics of the martyrs of ’98. (In 1912 she was pleased to receive a piece of bloodstained floorboard from the house where Lord Edward FitzGerald was apprehended; her derisive approach to Catholic ‘superstitions’ did not extend to the holy relics of nationalist martyrs.26) Bulmer Hobson was similarly preoccupied, and at this time Patrick Pearse’s cult of Robert Emmet was reaching new heights – along with his belief that Dublin had been ‘disgraced’ by its somnolent reaction to Emmet’s attempted putsch in 1803.

Up in Ulster, nationalists continued to cling to the idea of radical nationalism dissolving sectarian differences and overcoming the powerful network of the Ancient Order of Hibernians. Though by 1909 Hobson had privately become pessimistic about the non-sectarian prospects of the Dungannon clubs, this would not do for public consumption.27 A few Ulster Protestants could find their way to nationalism by odd routes, such as Rory Haskin – a Belfast Protestant who spent six years in the British Army, then joined the Orange Order and the UVF, before undergoing a Damascene conversion to republicanism when he attended a Freedom Club (an IRB front organization whose members included Hobson, Ernest Blythe, Cathal O’Shannon and Joseph Connolly).28 F. J. Bigger, as ever, remained sui generis: preaching the values of ’98 to his acolytes, but remaining close to Joe Devlin, also a life-long bachelor and a frequent visitor at Ardrigh (which he would eventually buy from Bigger’s estate). As politics in Ulster moved towards polarization, the boys’ parties continued unabated at the house on the Antrim Road and in Shane’s Castle; and, though Bigger was under police observation, the police sometimes joined in the partying too. After Bigger presented a stained-glass window to a local church in September 1913, his followers proceeded to Shane’s Castle and plunged into rowdy celebrations, breathlessly described by Roger Casement, who referred to his host with a Gaelic approximation of a clan title:

An Biggerac was in great form: not a chief merely but an emperor! Kilted; banners (6 or 7) pipers (7) pikemen (4) to precede him and clear the way wherever he went. I never saw anything like it. It makes me scream. He ‘processes’ now in walk . . . The Boys love it, and pipe go leor. He wound up with [an] R.I.C. constable’s cap and baton, and delivered a stump harangue thus garbed. Kilt etc. below, R.I.C. cap and baton above it, 2 a.m., in to Shane O’Neill’s castle on . . . Empire! The speech began: ‘Sons of the Empire! Children of the Blood! Will the sun never set on this great Empire of ours?’ Which was greeted with a howl of ‘Never! Never!’ immediately followed by the chauffeur, decked out in Orange robes, declaring he would ‘never, never surrender’! The fun is that the chauffeur is an Orange boy, a ‘Scotch Protestant’, so everyone took part, the three constables of Ardglass, poor souls, belts off, caps gone, and the pipes skirling like the devil, all singing ‘God Save Ireland’!29

This celebration of collaborationist ‘Ulsterism’, invoking the icons of both ‘sides’ in a spirit of camp homosociality, was the kind of culture where Bigger felt most at home; but for such romantics, the implications of the Covenant and the rise of the UVF held an ominous message. Two months after the occasion described by Casement, in more sober mode, Bigger made a visit to his ancestral territory around Templepatrick. Still hoping against hope that his traditionally minded unionist relatives could be converted to pluralist nationalism, he reported his impressions to Alice Stopford Green:

Home Rule was lightly treated – no fear – some hopes, no truculence. I heard no disparaging word and saw no cold eye, all was kindness & friendship. Of course I know their every phase of life and thought, their every word and action but yet what a distance there is between the road I am on, the one I have travelled and am travelling and the one they are on – They know the Hearts of Steel [a Protestant agrarian radical movement in eighteenth-century Ulster] & ’98 & dwell there and then the break comes – it must be the National schools [i.e. the effectively denominational system of education which developed from the 1830s]. How fine the next generation will be if we get an Irish Ireland atmosphere – they will lead any other crowd in Ireland in patriotism I am sure.30

But this was wishful thinking, and a few weeks later his description of New Year’s Eve celebrations at Ardrigh carried an ominously militarist implication:

all the boys present – some in kilts others in old Volunteer uniforms – all armed fully with rifles and pikes – pipes go leor & drums with standard. I received them at the door (a lovely clear cold frosty star-lit night) at midnight – then we had heavy firing of shot from the balcony and ‘A Nation Once Again’ from the pipes – then a quick march in fully drilled ranks down the road and then up the road ½ mile in tense excitement. The local police on night duty and very interested but came in for refreshments after saluting the standard. And so we heralded in 1914.31

As the critical moment of resistance to Home Rule approached, it seemed less and less likely that Irish unity could be found under a Bigger-designed goose-wing helmet.

Even as romantic a nationalist as Bigger’s friend Roger Casement had to wonder where the descendants of the 1798 republicans were now. Six days before the Covenant was signed on 28 September 1912, he watched the ‘appalling grim Ulster Hall faces’ marching past his Belfast window, and wrote to his cousin Gertrude, using family pet names:

I tremble for the piety of this realm, this Ulster so bathed in the tears of righteousness (self-righteousness), so washed in papish blood and cleansed in the furious sweat of riot. Pious, God-fearing, humble Ulster, only seeking the Christian path of self-denial, self-effacement, that leads to the narrow path of renunciation by which no papist may pass, to Harland and Wolfs [sic: Harland & Wolff, the Protestant ship-building firm], or any other means of employment . . . Adios my Geelet, Thy Scodge goes off to Corny O Gallogher [a celebrated traditional musician] full of fury against the ineffaceable ugliness of Carson & co: how truly awfully ugly he is!32

When the Covenant was signed a few days later, he wrote again: ‘I love the Antrim Presbyterians . . . they are good, kind warm-hearted souls, and to see them now exploited by that damned Church of Ireland, and that Orange Ascendancy gang who hate Presbyterians only less than papists, and to see them delirious before a Smith and a Carson (a cross between a badly reared bloodhound and an underfed hyena sniffing for Irish blood in the track) and whooping Rule Britannia through the streets is a wound to my soul.’ They must be wooed from their ‘perverted, abominable creed’; he added, prophetically, that he ‘prayed for the Germans’ and their coming to teach them a ‘Protestant’ lesson.33

Casement’s mind was already running on conflict. In late November 1913 he declared that an open confrontation with the opponents of Home Rule would be ‘far better than to go on lying and pretending – if only we could be left free to fight out our battle here ourselves’.34 But this brutal logic seems to have evaded most nationalist ideologues, who preferred to declare, as Patrick Pearse did, that it was a glorious thing to see arms in the hands of Irishmen, no matter who they were or for what purpose they were intended. Casement also felt, inconsistently, that ‘[The UVF is] the only really healthy thing. It is fine; it is the act of men; and I like it, and love the thought of those English Liberal ministers squirming before it.’35

The language of hyper-masculinity might be noted: arms were closely connected with the definition of manhood, as elsewhere in contemporary Europe. Practical implications were another thing. When the thought occurred to Pearse that Redmond might actually want to gain control of the Irish Volunteers in order to pit them against the UVF, he became intensely worried.36 More rational observers at this time also subscribed to the idea that the enmity felt for the British government among Northern unionists and Southern nationalists could bring them together in an unholy alliance: such a scenario was sketched in various unlikely quarters, including George Birmingham’s satirical novel The Red Hand of Ulster, and a Press Association interview given by the widow of Charles Stewart Parnell. Asked what the dead Chief would have made of the current political situation, she speculated that ‘Sir Edward Carson’s little army would have appealed strongly to him – only he would have tipped the Ulster rebellion into the Home Rule cauldron and directed the resulting explosion at England.’37

More surprisingly, this fantasy was subscribed to by people actually from an Ulster background, who might have been supposed to know better. Eoin MacNeill, whose political antennae were admittedly not the sharpest, caused a near-riot when he called for three cheers for Carson’s Volunteers at an Irish Volunteers meeting in Cork. In March 1914 he still saw the UVF as representing a development favourable to nationalism. ‘It would be simply heavenly,’ he wrote to Casement,

if the Government undertook to suppress our Volunteers and Carson’s together. Is there any way of getting them to do it? . . . We have them in a cleft stick. The question of arms need not discourage us. We have to get the young men to understand that now every one of them can get military training and can join in a permanent national militia to be ready for arming at any time and to be ready to come out on command.38

And the seer from Lurgan, AE, put his faith in the admiration felt by an advanced-nationalist friend on the day the Covenant was signed:

I found him with his eyes shining as though they were swimming in whiskey – though they were not – and he said to me ‘Isn’t it splendid! Isn’t it splendid. They won’t have it!’ and then he caught my psychological eye fixed upon him and he said ‘I know it is unreasonable. But there is something deeper than reason.’ Yes there was something deeper than reason. It was the powerful Irish character calling to the powerful Irish character – deep calling to deep – and it is upon this fundamental unity of character that I base my belief in the success of self-government.39

By this demonstration of their ‘powerful Irish character’, he thought, the Ulster unionists ‘endeared themselves to their southern fellow countrymen by this exhibition of their manhood, though its purpose ran counter to the political desires of Nationalists’. But such wishful thinking was doomed to disappointment, as was MacNeill’s wish to see both Volunteer forces suppressed by the government in 1914 – an event which he innocently believed would unite them in a common cause. Instead the events of 1912–14 destroyed many of the assumptions upon which idealistic Protestant nationalists believed an independent Ireland could be based.

Moreover, the attitudes of the revolutionary generation towards Ulster remained ambivalent. Piaras Béaslaí saw all Ulster people as aggressively bad-mannered and tediously talkative: ‘they are all the same, Catholic and Protestant.’ Rosamond Jacob’s opinions clearly prejudiced her receptiveness to Gaelic League history classes; after one of these she confided to her diary, ‘Strange what miserable worms passed for heroes in ancient Ulster & what childish creatures the whole nobility were.’ When other hardline nationalists like Terence MacSwiney reflected upon the North (which was not often), they were in no doubt: Ulster could and must be made to see that its interests lay with Ireland, not Britain. Helena Molony dismissed the UVF as merely an outburst of ‘insolence and self-conceit’. Those who had actually lived in Ulster were more realistic; Margot Trench noted in October 1914 that the pro-German rhetoric of nationalism would mean ‘goodbye to unity between north and south for two generations’.40 But few of her friends were as pessimistic.

Many advanced nationalists, in any case, saw no point in trying to appease Northern fears. Liam de Róiste was suspicious of Protestants in general. Attending a commercial course at the London School of Economics in 1914, he was disappointed to find that an Irish fellow student ‘is a Protestant, so not as nice a type as one would like’, though he amended his opinion when he found that his colleague went to Speakers’ Corner on Sundays and harangued audiences about the iniquity of British government in Ireland.41 Northern Irish Protestants, however, were considered past redemption, and de Róiste dismissed them in his 1915 diary as ‘Irishmen who do not believe in Irish nationality’.

They are as aliens in Ireland. For a good while I was of the opinion that it was possible to win them, by argument or a show of good feeling, to Irish nationality. I have modified that opinion somewhat. It will be easier to mould them into the Irish Nation by standing up to them as men. Their traditions, so carefully fostered by the Big Brother, lead them to despise Irish nationalists. They will not be shaken in that by argument, or false tolerance. To make them respect Irish nationality they must be fought. ‘Civil War’ some will cry. Well, there are worse things than civil war – national slavery for instance.42

This echoed not only a famous utterance of Patrick Pearse, but the declarations of Ulster Protestant Covenanters, in the distant as well as in the recent past. The rise of an armed citizenry, North and South, suggested to idealistic nationalists the revival of that supposed political unity between Catholic and Protestant in 1798, so often invoked and so hard to recapture. But it also evoked more ominous historical associations, such as the Protestant Covenanters of the seventeenth century, and a longer memory still of implacable antagonism.

Historical precedents were a shaky guide to the kind of confrontation now brewing. Another marked divergence from previous crises was that the armed citizenry now included women. The contribution of women to cultural organizations had already been established and was decisively influential; their input into political bodies was a thornier issue, given the fact that the suffrage cause loomed over so much (and mobilized so many different kinds of women). Maud Gonne’s organization, Inghinidhe na hÉireann, was influential beyond its numbers, and served as a training-ground for a generation of political women. By 1909 the newspaper Bean na hÉireann, as mentioned in the last chapter, was taking a very militaristic line indeed. Volunteering suggested another route, and in April 1914 a new organization emerged, Cumann na mBan. Its role was ‘to assist in arming and equipping a body of Irishmen for the defence of Ireland’, which suggests a definitively auxiliary role in relation to the male Volunteers; but strong elements within the movement suggested an impetus towards playing a more independent part. The membership was generally republican, middle class and well educated. Cumann na mBan women were a much less amorphous group than the National Volunteers, whose swelling numbers brought in a wider and wider range of moderate and gentry elements, especially after the outbreak of international war. Above all the women no less than the men were preoccupied with bearing arms, as their emblem of a stylized rifle suggests.

As the Volunteering movement spread across the country, and became ostensibly taken over by ‘respectable’ elements, its relationship to other mass political movements, notably the Irish Parliamentary Party and the Ancient Order of Hibernians, remained complex and uncertain. The part played within the movement by IRB extremists was less ambiguous, but more secretive. The experience of Frank Drohan (born in 1879), a coachbuilder’s son in Clonmel, was probably typical; by 1910 he was using the local Gaelic League branch as a cover for an IRB cell. In 1911 Seán MacDermott visited town and set up a Munster network. By 1913 three IRB circles existed in Clonmel, and these formed the basis of the local Volunteers; they were trained at night by an ex-British Army sergeant and bought guns under the guise of ‘hardware’ from Hearne’s ironmongers in Waterford.43 A Sligo schoolteacher, Alex McCabe, followed a similar path: he joined the IRB when studying in Dublin, and on his return to Sligo used the local Volunteers corps as a cover for setting up IRB circles dispersed around the county. The ubiquitous Seán MacDermott was involved here too, and probably the Sinn Féiner priest Father Michael O’Flanagan of Cliffoney.44 In Dublin, another IRB member, Michael Stainer, shop assistant and treasurer of the Colmcille branch of the Gaelic League, was also Quartermaster of the Dublin brigade of the Volunteers; his job at Henshaw’s ironmongers gave him access to firearms, and enabled him to reroute arms and ammunition from his employers to his comrades.

Less productively, Seán T. O’Kelly was detailed to fund an arms-buying trip to London by getting a large amount of gold from a sympathetic bank manager in College Green. (Significantly, the bank manager was not an IRB contact but provided help because ‘as an ardent Home Ruler he believed the Volunteers had as much right to be armed as the Ulster Volunteers.’) After staggering around London weighed down by bullion, O’Kelly returned to Dublin without guns; the gold, however, found its way to the tireless Seán MacDermott, who kept it for IRB purposes. By mid-1913 Piaras Béaslaí’s diary records his attending regular IRB meetings, the purchase of detonators, and ambitious discussions about the use of aeroplanes and physical force. Around the same time Geraldine Plunkett remembered Liam Mellows arriving at 17 Marlborough Road with two Gladstone bags full of ammunition and gelignite, which were subsequently stored there. And the Irish Volunteer assured its readers in May 1914: ‘The man who has once handled a rifle and is not smitten with the desire to own one is not an Irishman.’45

These activities and ambitions were helped by the lapse of the 1881 Peace Preservation Act in 1906; legal restrictions on arms importation were now distinctly sketchy, and police had to rely upon a rather open-ended Gun Licence Act to apprehend arms. Attempts to limit importation were laughed off. A scornful letter to the press from O’Rahilly in May 1914, calling for guns for the Irish Volunteers, added: ‘The [Royal] Proclamation [of the previous December, forbidding the importation of arms and ammunition into Ireland] need worry nobody. The latest decision of the Government has proved that the Proclamation only forbids the entry of small quantities of sporting goods – Military Rifles in lots of 50,000 and cartridges by the million are freely admissible without interference, prosecution or punishment.’46 What is striking overall is the importance placed on the possession of guns, and the lengths gone to in acquiring them. ‘WE WANT RIFLES,’ wrote Liam de Róiste to Roger Casement in June 1914, having apparently mastered his earlier doubts about violence. ‘We are thirsting for rifles.’ For his part, Casement was now preaching that ‘revolution’ must replace ‘resolutions’. ‘If the people of Ireland wanted [freedom] as much as the people of Ulster did not want it, they must be prepared to fight for it.’47

Meanwhile, the public face of Volunteering remained outwardly respectable, with recruits representing a fairly wide class spectrum. As Redmondite influence became superficially predominant, ex-British Army officers and local gentry climbed on board. The diaries of Diarmuid Coffey, who worked as a Volunteers organizer first in County Clare and then at the Dublin HQ, provide vivid vignettes of this phase of the movement. Coffey was an intellectual, subtle, slightly hesitant figure, from a highly cultured family very much in the Dublin intellectual swim. His father George, Keeper of the Irish Antiquities in the National Museum and a painter and writer as well as a noted archaeologist, came from an Ulster Catholic background. From the 1880s he was a familiar figure in the intellectual nationalist world centred on C. H. Oldham’s Contemporary Club and John O’Leary’s circle. Diarmuid’s mother, Jane L’Estrange, from an old Protestant family, was involved in the Irish Literary Theatre, and the Coffey house in Harcourt Terrace was a centre for cultural happenings, such as the first performance of AE’s play Deirdre. Diarmuid, an only child, went to Trinity and became a barrister, but preferred a literary life. A language revivalist and Sinn Féin sympathizer, his nationalism was of a fairly moderate kind, and his job as secretary to Colonel Maurice Moore in the Volunteers headquarters from 1914 to 1916, while not unduly demanding, gave him a detached vantage point from which to view the build-up of tension in Ireland.

Coffey was in love with the more feisty, emotional and radically nationalist artist Cesca Trench, whose diaries, drawings and paintings are a valuable record of the life of the privileged young in this era. Coffey, though in some ways as anti-British as Cesca, remained a supporter of Home Rule in these years, and disagreed with her about many issues (not least women’s suffrage); his diaries show his intense suspicion of ‘The O’Rahilly’ and more radical and separatist elements within the Volunteers. Yet he, along with so many, was preoccupied with putting guns in the hands of Irish people, and he was one of the party who sailed on the yachts belonging to his friends Erskine Childers and Conor O’Brien in July 1914 to collect guns from Germany and arm the Volunteers – an episode which he recorded in his diary, and wrote about publicly afterwards. The party included Childers’s wife and Mary Spring-Rice, a radical nationalist from an impeccable Ascendancy background: the arrival of the main consignment of guns at Howth, just outside Dublin, was carefully choreographed as a major publicity coup for the Volunteers.

The Howth enterprise was – yet again – undertaken in response to a rival Northern initiative: the UVF had run in guns to Larne, County Antrim, on a large scale some weeks before, defying the government’s attempt to impound arms en route to the North. (They had managed to seize 55,000 rounds of ammunition being shipped from Birmingham, but far more was getting through.48) This, as ever, enabled the UVF to present itself as a more efficient paramilitary force: its own publicity photographs indicate its possession of motor-cars, much emphasized at the time, and the financial resources and class position of many of its supporters. The plan for a rival project of nationalist defiance was first planned by Hobson, with finance arranged by Casement, who raised £1,500 from well-wishers.49 Erskine and Molly Childers provided £400 as well as one of the yachts; after a series of missed encounters and communications gone astray, the arms were transferred from a German tugboat to the yacht, an event rhapsodically described by Childers’s American wife.

I wish you could have seen the scene. Darkness, lamps, strange faces, the swell of the sea making the boat lurch, guns, straw everywhere, unpack[ed] on deck and . . . handed down and stowed in an endless stream; no supper, chocolate thrust into mouths of the crew and a mug of water passed around when frail nature nearly spent – the Vaseline on the guns smeared over everything . . . men sweating and panting under the weight of the 29 ammunition boxes – heavy and hard to handle . . . I nearly slept as I stood and handed down guns. It was all like a mad dream, with a glow of joy and the feeling of accomplishing something great at the back of it to keep the brain steady and the heart unperturbed.50

The Asgard sailed openly into Howth Harbour on 26 July. By contrast with the heavily motorized UVF, the National Volunteers transported many of their guns back from Howth by bicycle, each weapon reverently laid across the handlebars. (Taxis had to be hired to transport the ammunition.) Nor were the guns themselves at all up to the standard of those purchased by the well-off and efficient Northerners. And they disappeared in various directions, not always intended by their well-meaning couriers. It should be remembered that the Childerses were still Redmondites at this stage, and thought they were running guns in order to safeguard the Home Rule Act. Molly Childers claimed that her husband subsequently ‘hurried back to London’, where he ‘received congratulations from members of the Cabinet; the gunrunning was regarded as most helpful to the Government in their difficulty with Ulster.’51

They would shortly be disabused of this belief. Colonel Moore subsequently remarked to Coffey: ‘The Sinn Féin are going to have a celebration all over Ireland if they can and want to claim the gunrunning as their own whereas all they did was to steal the arms after it was over.’52 But, as ever, the vital thing was to see ‘guns in the hands of Irishmen’: the fervent account in Cesca’s diary is a good reflection. Standing on the quay at Howth, ‘we cheered and cheered and cheered, and waved anything we had, and cheered again . . . To see and hear, that was the best thing that ever happened to me in my life. We went to some policemen who were standing there and said, “Isn’t it grand?” “It is,” they said, “it’s great”, and broad smiles all over their faces.’53

The police were in fact notably acquiescent, declining to interrupt the Volunteers on their triumphant passage into the city; the Under-Secretary, Sir James Dougherty, similarly advised against attempting to confront the gun-runners. But there was an unsuccessful attempt at interception near Clontarf by a detachment of the Scottish Borderers, who subsequently fired on a hostile crowd at Bachelor’s Walk and killed three people, with a fourth dying later in hospital. Yet again, the contrast with the authorities turning a blind eye to UVF importations of arms was bitterly noted, and another Rubicon passed. Liam de Róiste, studying in London, felt an impotent rage. His thoughts were already turning to dynamite, and the news of Bachelor’s Walk confirmed it. ‘I could have gone out in the streets, had there been anyone with me, and fought the English police or soldiers . . . I feel I could go to Dublin at once were I wanted there, or back to Cork.’ Piaras Béaslaí, who heard the news when entertaining Killarney with his travelling players, shared in the general sense of outrage.54 The huge public funerals were headed by the Volunteers, with their newly imported Mausers well to the fore. Mary Kate Ryan, whose opinions were becoming implacably anti-Redmond, wrote to her sister Min after attending the funeral of the fourth victim; she reported that the Citizen Army were much in evidence ‘& an immense crowd of Dublin working people. Not one respectable person else. They would not embarrass England by acknowledging such an atrocity!’ For extremists, the desired crisis was one step nearer after Bachelor’s Walk. ‘Great news except for the people who were killed and their friends,’ Rosamond Jacob recorded in her diary. ‘You’d think it ought to have a very good effect.’55

V

The events of the fateful summer of 1914, and the government’s inept and pusillanimous responses, had put Redmond’s Home Rule strategy on the defensive; the Irish Volunteer’s reaction to the Curragh episode in March now seemed prescient. ‘We sacrificed “unconstitutional” methods for constitutional, and if at the last minute England tells us that her constitution is a sham we must take her words and take back the arms we dropped.’56 With underlying tensions within the Volunteers threatening his apparent dominance, deadlock over Ulster’s resistance to Home Rule, and the escalating tempo of radical-nationalist emotion, the Irish Parliamentary Party leader needed the appearance of a deus ex machina. It came, as so often, from an utterly unexpected direction, when Austria’s ultimatum to Serbia precipitated a European crisis, and Britain declared war on 4 August after Germany invaded Belgium.

The ensuing conflagration has, especially in recent years, come to be recognized as one of the defining points of modern Irish history. For one thing, an enormous number of Irishmen voluntarily enlisted, fought and died: the amnesia imposed on this phenomenon by the independent Irish state from the 1920s has been amply atoned for since. The motivations behind enlistment could be various. Tom Barry recalled that, as a seventeen-year-old, he ‘went to the war for no other reason than that I wanted to see what war was like, to get a gun, to see new countries and to feel a grown man’.57 When he returned to Ireland he became a legendary IRA combatant. Others followed a similar route, but the vast majority enlisted to fight Germans rather than to learn skills which could be later turned against the British. Above all, the language of militarism was now given shape. Kevin O’Shiel’s memoir recalled that, before August 1914, people like him thought that physical force was a distant possibility; but the concept now emerged fully fledged, like a ‘mad goddess’.58

And the war brought to a head the split already festering within the Volunteers. With Home Rule apparently stymied by Ulster resistance, Redmond’s tactic was to throw the support of the Volunteers fully behind the war effort, reckoning that a short and victorious war would forge a feeling of unity between Volunteers North and South: that chimerical hope once shared by MacNeill, Bigger and others. In Redmond’s calculation, the enthusiasm for the war effort expressed in unionist circles throughout the island would be turned to good effect, undercutting the opposition to Home Rule in the north-east – where the war effort was most fervently embraced. The UVF membership enlisted in hordes, effectively forming their own division within the army.

Recruitment to the British Army was less spectacular outside Ulster, but the numbers of the Irish Volunteers were hugely swelled by war fever. The membership of the movement peaked at about 190,000 in September 1914, an astounding proportion of the population of the country – which also suggests that the movement was very far from being composed principally of separatist republicans. While Rosamond Jacob saw Redmond’s strategy as his ‘crowning act of treason’, and Mary Kate Ryan believed that he had now ‘done his worst for the country’, moderate nationalism at first fell in behind him.59 The vast majority of the membership followed Redmond’s pro-war line when the movement finally split in late September 1914. They included, very prominently, the charismatic nationalist politician and intellectual Tom Kettle, who committed himself whole-heartedly to the war effort and the Allied cause, and crusaded passionately for the cause of recruiting. For separatists, the support of the movement for Redmond was an appalling blow, as Desmond FitzGerald later remembered.

The movement on which all our dreams had centred seemed merely to have canalized the martial spirit of the Irish people for the defence of England. Our dream castles toppled about us with a crash. It was brought home to us that the very fever that possessed us was due to a subconscious awareness that the final end of the Irish nation was at hand. For centuries, England had held Ireland materially. But now it seemed she held her in a new and utterly complete way.

Our national identity was obliterated not only politically, but also in our own minds. The Irish people had recognized themselves as part of England.60

Working for Colonel Edmond Cotter, Edmond the uneasy Chief-of-Staff at Volunteers HQ in Dawson Street, Coffey had noted ‘a stream of Unionists’ coming in to join as soon as war was declared: most of them ‘bounders’ and ‘incapable asses’ who wanted to turn the Volunteers into a branch of the British Army.61 Coffey found himself caught between such people and the IRB members of the Volunteers committee such as Bulmer Hobson and Michael Judge, and observed both sides with a certain contempt; he particularly despised O’Rahilly as ‘a very useless type of person [who] swanks about in uniform and is just like a comic opera hero’.

Coffey’s diary indicates that the split in the Volunteers, after Redmond publicly committed them to full-blown support of the war effort, had always been a mere matter of time. It came as the climax of a long campaign behind the scenes to drive out the subversive element. As early as 1 September, he and others were urging Redmond to ‘execute a coup d’état’ and to set up ‘a strong central authority’; Eoin MacNeill, irresolute as ever, was at first in on the scheme but backed out. ‘He does not stick to a settled course,’ Coffey fulminated; ‘I liken him to a man trying to swim to Tir na nÓg [the mythical Gaelic land of eternal youth] & thinking each point of the compass is it until he finally swims round in circles. Another man said he always conspires with each man against the man he conspired with last.’62 Coffey remained with the moderates, doggedly believing that supporting the Volunteers might be a way of bringing pressure on the government to honour Home Rule; but, moving as he did through a wide social and political circle, he realized that this was not a view universally held. ‘Dined with the Markieviczes to meet [James] Connolly the labour leader,’ he recorded on 5 September 1914. ‘I did not like him much. He is very red-hot anti-British which rather surprised me but I don’t think I would trust him as far as I could throw him. He was very strong on how wrong it was to “give soldiers to the enemy”. He may be right but I can’t think of any way of making the I. V. [Irish Volunteers] any good unless we get help from the War Office & if the I. V. fail how can we insist on good terms in the amending bill [intended to arrive at an agreed version of Home Rule]?’ Under the violently unionist General Kitchener, ‘help for the Irish Volunteers’ was never going to come from the War Office, but Coffey only realized this later.63

Nonetheless, in the early months of the war, the main Volunteering movement apparently resembled a Home Guard, continuing to follow British Army methods and models of military training, and staffed by people who believed in the war effort: not least as a strategy for advancing Ireland’s claims to national autonomy in a post-war dispensation. The Gaelic scholar Eleanor Hull wrote excitedly to Coffey from London, rhapsodizing over ‘the wonderful change that seems to be coming over public opinion in Ireland since the passing of the Home Rule Bill’ and the potential for national unity: ‘with Redmond recruiting for the British army and the Ulster covenanters going out to die for Catholic Belgium, what may not be accomplished!’ Coffey poured cold water on her enthusiasm, telling her that encouraging recruitment ‘will by raising opposition and counter movements do as much harm as good to the cause you have at heart’. But he defended Redmond’s pro-war policy to his friend Kevin O’Shiel: the point was ‘to educate the people into knowing clearly what they do want, what are the difficulties with which they are faced, what the present Home Rule Act really means, and how that Act should be altered to make it a base upon which a future Irish Constitution can be framed.’64

This showed a sophisticated understanding of the difficulties confronting Redmond, and his attempts to finesse them by negotiating with Ulster unionists behind the scenes. But Coffey’s judicious detachment was hard to maintain after the split and secession following the Irish leader’s speech at Woodenbridge, County Wicklow, on 20 September 1914, where he committed the Volunteers to supporting the war effort on the battlefront abroad as well as to the defence of the island of Ireland. This was a step which the radical element could be guaranteed to oppose, which may well have been Redmond’s intention. The movement split at once, publicly and traumatically. The minority who seceded (taking with them the name ‘Irish Volunteers’) were the IRB-dominated element, whose feelings about the opportunities afforded by the war were very different. Some were frankly and even passionately pro-German, notably Roger Casement; for others, such as Terence MacSwiney, the years of rhetoric and polemic had at last produced a proto-nation in arms. MacSwiney’s Volunteers uniform became a central part of his revolutionary identity, worn on all possible occasions, including at his marriage to Muriel Murphy a couple of years later. Thomas MacDonagh had also flung himself into the movement from the beginning, writing bloodthirsty marching songs instead of mystic poems;65 after the split, his fervour knew no bounds. All of the secessionists, like Seán MacDermott, saw an international war as the classic opportunity for a Fenian insurrection against Britain.

Not for the first or last time in Irish history, in the case of a split the future was on the side of the dissident minority. Redmond’s Volunteers would die in great numbers on the international war front, while the structure of the main Volunteering movement at home decayed and Hibernian-style politicking took over. By late 1915 the majority movement was a ghost of its former self, as Diarmuid Coffey sadly recognized. ‘Had a talk with some of the officers. They all seem to think that the movement is petering out. They lay the blame chiefly on the committee & say that they the committee only want the Vols for the purposes of ward politics. I am afraid there is a good deal in this.’ This is borne out by local studies which describe Volunteer companies succumbing slowly to ‘paralysis’ as members left for the Front and the remnant became immersed in political bickering.66

Meanwhile the rump of extremists laid plans for radical action, and defined themselves decisively against the Home Rule enemy. By 1915 the dissident Irish Volunteers were engaging in pitched battles against the AOH at political demonstrations. The split had clarified and focused their mission: as one of them put it much later, ‘we had got rid of any ambiguous feeling which existed that we were only bluffing.’67 This was not apparent to the more cynical elements of Irish opinion. One of the more extreme of the IRB military planners was the poet, mystic, playwright and flamboyant revolutionary Joseph Plunkett, who dedicated himself to distributing propaganda, planning military manoeuvres and constructing wireless sets through which he hoped to publicize the insurrection when it came. He was also immersed in plans to contact subversive elements abroad, employing his sisters on secret missions to extremist Irish-Americans. Though severely ill once more with tuberculosis, he himself would make a secret visit to Germany to arrange for German military aid in the summer of 1915. To others he seemed an unlikely rebel leader: certainly in the view of his doctor, who was amused at the earnest acolytes who trooped in to visit Plunkett in his nursing-home.

I remember once finding a group of them seated around his bed with notebooks and pencils in their hands, while he was sitting up in bed, apparently giving them instructions. I, frankly, did not take this at all seriously and remarked: ‘Napoleon dictating to his marshals’ – a remark which was not well received. On another occasion I joked with him, saying, ‘I suppose you sleep with a revolver under your pillow’ and to my surprise he said, ‘I do’ and pulled one out.68

The years of agit-prop work in magazines and theatre, the mystical nationalism absorbed from Pearse and MacDonagh, perhaps also the implacable war forged against his parents along with his sisters and brother, and now this world-historical opportunity: events had propelled Plunkett into the position of revolutionary hero. He was engaged in a double race against time: an insurrection must happen before the war ended, and before his own death. With his brother George and his sister Geraldine, he was largely living at the mill and farm complex at Larkfield in the Dublin suburbs, which had become more of an armed camp than ever. The settlement acted as a magnet for young men of Irish descent returning (or immigrating) from Britain; they had come to Ireland to avoid conscription and join another cause. At Larkfield they lived in semi-military conditions: drilled by George Plunkett, fed by the Plunkett sisters and employed in making ammunition – as recalled vividly in the absorbing autobiography of Joe Good. Séamus O’Connor visited Larkfield and found ‘a motley collection of men’ manufacturing makeshift pikes – ‘simply sharp spikes fixed on ashen handles. It made me sad when I saw them.’ Joe Good’s account bears this out, adding details of how they also constructed shotgun cartridges, and crude hand-grenades out of sections of down-pipe, in expectation of a coming struggle. ‘We had a good deal of fun, a lovely view of the Dublin mountains through the windowless frames [of the barn], and bragged that we were the first Irish garrison since that of Patrick Sarsfield.’69 These refugees were known by the Plunketts as ‘the lambs’: possibly, as Joe Good sardonically pointed out, because they were to be led to the slaughter.