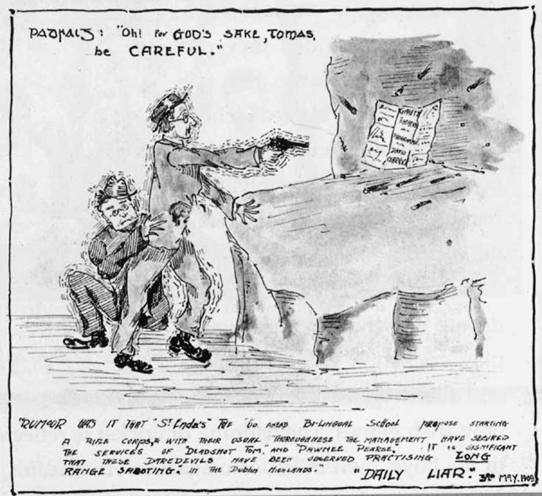

An unconsciously prophetic cartoon by the St Enda’s pupil Patrick Tuohy, responding to the school’s acquisition of a rifle range in 1909; it mocks the alarmed reactions of the supposedly gentle and pacific figures of Patrick Pearse and Thomas MacDonagh (‘Deadshot Tom and Pawnee Pearse’). Both would fight in the Rising seven years later (as would Tuohy himself) and be executed for it.

I lived on a mountain top where there was no need for speech, even. I felt an understanding, a sharing of something bigger than ourselves, and a heightening of life. People could be more expressive, natural and affectionate. They were direct, and immediate contact was not difficult. Older people had no conscious out-thrust of age or experience; we all shared the adventure.

– Ernie O’Malley, On Another Man’s Wound (1936)1

I

Many of the people whose lives run through this book had dreamt of an Irish revolution against British rule, and welcomed the advent of world war as both enabling and sanctioning such an eventuality. Several were involved in the frenetic planning of an insurrection originally tabled for Easter Sunday 1916 and instigated by the inner Military Council of the IRB: notably Joseph Plunkett, Seán MacDermott, Tom Clarke, Patrick Pearse and Thomas MacDonagh. Constance Markievicz’s position in the Irish Citizen Army, and her closeness to James Connolly, brought her near the centre of intrigue; other ICA members, such as Helena Molony, were also fully informed.2 A larger number were poised on the outer circles of conspiracy; Plunkett’s sisters Geraldine and Mimi, and his brothers George and Jack, were not privy to the full plan until the last minute. Roger Casement was on his own revolutionary mission, though he knew a rising was imminent. Senior Volunteers in Dublin, including Éamon de Valera, were briefed by their IRB contacts. Prominent Irish Volunteers outside Dublin, such as Terence MacSwiney and Liam de Róiste in Cork, Denis McCullough in Belfast, and Pat McCartan working as a doctor in Tyrone, had been equally aware since January that plans were afoot. But they were not closely informed, especially if – like McCartan – they had earlier aired doubts to IRB colleagues about the wisdom of such a move. Richard Mulcahy, for instance, was more or less talked into it at the last minute. Specific details were given to McCartan and McCullough only on Good Friday.3 Seán T. O’Kelly was closer to the Military Council, but even he was held at a certain distance.

Others who had been active in the preparation of a revolutionary mindset were openly sceptical about the feasibility of a rising without guaranteed German aid, and were therefore kept in the dark. A week before Easter, Min Ryan organized a fundraising concert for the Volunteers at the Foresters’ Hall on Palm Sunday; here Bulmer Hobson made a speech implying that some rash action was in the air, and counselling caution, to the fury of several of his listeners. Eimar O’Duffy was of the same mind, as were Michael O’Rahilly and Arthur Griffith. And for many romantic adherents of the idea of rebelling against British rule, such as Rosamond Jacob, Cesca Trench and Maud Gonne, the Rising would come as a bolt from the blue. To some, it appeared as the inspirational annunciation of a long-promised epiphany. For others, the reality of violent revolution would awaken strong feelings of ambivalence, which were concealed at first but grew with time. The events of Easter Monday and following days would be recorded, preserved, mythologized and built into a narrative of liberation; the process would reaffirm the sense of being a special generation. The expectation of taking part in a great symbolic act had been imprinted on their consciousness through years of conditioning. The insurrection at once actualized that moment, and brought them up against reality, changing everything that had gone before. For this reason, the events of the Rising and its aftermath need to be rehearsed, as does the part played by several of the people whose lives and experiences have been traced thus far.

Despite the background of ostentatious subversion surveyed in the last chapter, the planning of the insurrection that burst into flame on 24 April 1916 remains oddly obscure. On some matters, at least, the revolutionaries managed to preserve a certain discretion – not least because they had to deceive so many of their colleagues as well as the authorities. By February 1915 those in touch with the extreme faction knew that a rising was planned.4 Between then and May, the secretive inner group of IRB strategists called the Military Council was established; this included Patrick Pearse, Éamonn Ceannt and Joseph Plunkett; Tom Clarke joined in September, along with MacDermott (whose anti-recruiting activities had recently earned him a gaol term under the Defence of the Realm Act, which was increasingly restricting the movements of many would-be revolutionaries). In January 1916 James Connolly would be co-opted, after frantic negotiations following the discovery that his Citizen Army was planning its own putsch before the war ended. Plunkett’s friend Thomas MacDonagh joined late, in April 1916. Those who had been key figures in the Volunteers, but who were now excluded from this inner circle, included Bulmer Hobson and Eoin MacNeill; an enduring schism had been created by the traumatic separation over accepting Redmond’s nominees on to the Volunteer command in the summer of 1914, for which Hobson in particular would never be forgiven. MacNeill was about to incur even greater obloquy when he countermanded the insurrectionary order to Volunteer units during Holy Week 1916, leaving the inner circle to launch a desperate and essentially doomed venture on their own.

MacNeill had tried to restrain his insurrectionist colleagues at the Volunteers’ headquarters in early 1916, and he was more closely informed about plans during the run-up to rebellion than he would later imply. McDermott had driven out to MacNeill’s Rathfarnham house on Sunday, 16 April (taking Seán T. O’Kelly and two Ryan girls for ‘cover’), and briefed him about plans for the following weekend.5 During the following week MacNeill was kept irresolutely on side, persuaded by doctored documents threatening a draconian crack-down by Dublin Castle on the Volunteers, enterprisingly leaked on the Wednesday before Easter. This was one of the eventualities defined by the radicals as justification for an insurrection, along with the imposition of conscription or a German invasion. More bizarrely, further justification was provided by assurances from several members of the Plunkett family, well in with the Vatican, that the Pope approved the venture.6 MacNeill then endorsed instructions to Volunteer battalions, telling them to be ready for defensive action and to resist disarmament by government troops; the step from there to an actual rebellion would be a very short one, as he must have realized, though he heard the details so late in the day.

Summonses were delivered to Volunteer brigades all over Ireland, often by women couriers, on Thursday, 20 April, and on Good Friday. O’Kelly’s was issued by Patrick Pearse’s brother Willie, summoning him to Beresford Place at 4 p.m. on Easter Sunday. ‘You will provide yourself with a bicycle, a street map of Dublin City, a road map of Dublin District and a field message book. You will carry full arms and ammunition, full service equipment (including overcoat) and rations for eight hours.’7

But by Saturday everything had been thrown into confusion, precipitated by Roger Casement. German aid was the sine qua non for successful insurrection, and this had been intensively canvassed during 1915. Casement was unhappily resident in Berlin, after a disastrous period trying to raise German support in New York, where local Irish-Americans were nonplussed by his frenzied declarations and emotional manner. (The painter John Butler Yeats thought he was in the throes of a nervous breakdown, likening him to ‘a very nice girl who is just hysterical enough to be charming and interesting among strangers and a trial to his [sic] own friends’.8) Moving to Germany exacerbated his highly strung manic state, not helped when Joseph Plunkett appeared in Berlin. Plunkett brought with him a beguiling and detailed plan for the German authorities, outlining a concerted effort underpinned by German arms and an invading force. The failure of the Germans to be convinced by this odd couple had far-ranging consequences. Casement plunged violently from hero-worshipping the Reich to denouncing German perfidy; his own failure to mobilize more than a few Irish prisoners-of-war into an ‘Irish Brigade’ compounded the disillusionment. Exhilarated by the brotherhood of Volunteering and by having shaken off the trammels of imperial service, he now became immersed in violent depression. ‘Oh Ireland, why did I ever trust in such a government . . . they have no sense of honour, chivalry or generosity. They are cads. This is why they are hated by the world and why England will surely beat them.’9 (As he would eventually realize, he was also being betrayed by his companion and lover, a shifty Norwegian sailor of fortune called Adler Christensen, who accompanied him back to Europe and embarked on a risky double game with the British diplomatic contacts.)

Casement, like his projected ‘Irish Brigade’ of fifty-six chancers, was by now a distinct embarrassment to the German high command, and out of touch with the conspirators at home; he heard of the insurrectionist plans, and the limited arms shipment offered by the Germans, only from a fellow Volunteer who had come to Germany to join the Irish Brigade, the shadowy Robert Monteith. With some relief the Germans agreed to transport Casement to Ireland by U-Boat, where he intended to put off any projected insurrection. With Monteith and another Irish Brigade member, he landed on a Kerry beach on Good Friday 1916 and was subsequently arrested, partly thanks to the inept organization of the local Volunteer battalion under the famously inefficient Austin Stack. Influential rumours at once raced off in several directions, compounded by the scuttling of an accompanying steamship with an arms cargo. The news persuaded the British authorities that an attempted rising, which they assumed was to have been led by Casement, had been short-circuited; warnings of the plans for an Easter insurrection had been relayed from intelligence sources in Washington and elsewhere, and reached the very highest sources in London, but were now cavalierly ignored.

To rebels in the know, the events in Kerry boded the end of any substantial German aid, but in the atmosphere of unsubstantiated rumour, the gullible could be persuaded to believe that it indicated hopes of a real invasion; Annie MacSwiney was told on the Wednesday of Easter Week by Tom Clarke, with ‘joyous elation’, that help was on the seas from Germany and that the Kaiser had recognized the Republic of Ireland.10 MacDermott and MacDonagh had been broadcasting this probability to sceptical colleagues for weeks. Ruminating later on the part played by MacDermott, McCartan judged that his old Dungannon Club comrade ‘was bright and energetic but mentally superficial; he had not an idea in his head when Hobson took him up & directed his “education”. . . he was cunning rather than clever, would do a crooked thing if it served his purpose.’ Denis McCullough wondered if MacDermott was deluding himself as well as others, and McCartan felt the same was true of Plunkett. ‘He deceived everyone about the great success he had in Germany re guns & support & probably deceived himself as well.’11

However, as the significance of Casement’s lonely journey home and its fallout became clear, the Volunteers leadership were precipitated into frantic meetings. Following his Wednesday instruction to Volunteers to prepare for defensive warfare, MacNeill was informed by a delegation of ‘moderates’ (Hobson, ‘Ginger’ O’Connell and Eimar O’Duffy) the next day that this was a cover for an actual insurrection planned for Sunday. An angry confrontation with Pearse confirmed this. On Friday, MacNeill was swayed by the rumour of a German landing in Kerry, but by Saturday night he had shifted his ground again, realizing how far he had been misled. He produced a final decision on Saturday night and countermanded the mobilization orders. With unwonted decisiveness, MacNeill got this into the Sunday-morning papers, effectively blocking most of the planned Volunteer manoeuvres. Individual orders to a similar effect were frantically conveyed to provincial leaders, many of them delivered by Michael O’Rahilly, travelling expensively by taxi.

For the members of the Military Council, this was almost unbearably traumatic; rage, tears, lamentations and murderous intentions towards the ‘moderates’ were widely recalled by those who witnessed the frenetic gatherings on Sunday at Liberty Hall, Larkfield and other rebel conclaves. (Constance Markievicz offered to shoot Hobson and MacNeill herself.) The day that had been designated for the insurrection passed without public incident, though many Volunteers indeed assembled as originally instructed, only to disperse in an atmosphere of confusion and anti-climax. But by Sunday night, among the leaders at least, a different and more exalted mood had taken over. They would seize the moment nonetheless, attempt to countermand MacNeill’s countermanding order, and mount an insurrection to preserve, on one level, the soul of the nation (a recurring phrase, significantly now adopted by the Marxist James Connolly) and, on another, their own revolutionary amour propre.12

The printing of their soon-to-be-historic ‘Proclamation of the Irish Republic’ went ahead, on the presses of the Workers’ Republic. And their plan would follow Plunkett and Pearse’s strategy of a spectacular uprising in the capital city, seizing central buildings and barricading streets, rather than the more pragmatic (and prophetic) outline of eventual guerrilla warfare across the country, originally advocated by Hobson. Connolly had also made a special study of urban risings in European cities, believing that in such circumstances ‘civilian revolutionists’ had the advantage over regular armies. But, above all, a rising in Dublin would raise the spectres of Lord Edward FitzGerald, Robert Emmet and the iconic figures of 1798, so omnipresent in the imaginations of the revolutionary generation – rather than the damp squibs of rural skirmishes in 1848 and 1867. Symbolic weight was already counting for more than practical methods.

II

Plunkett would later claim that ‘everything was foreseen, everything was calculated, nothing was forgotten.’13 But the precise, heavily theorized and rather classical stipulations which he liked to lay down (‘Napoleon dictating to his marshals’) were not a very accurate prognostication of the events of Easter 1916 in Dublin. The chaotic and last-minute nature of the leaders’ deliberations was reflected in the way that the insurrection began. Seán MacDermott arrived at the revolution in a motor-car, with Tom Clarke; they were driven to the corner of the General Post Office on Sackville Street, where around midday they met a detachment from Larkfield, who had arrived by tram (their fares paid, as usual, by Plunkett money). The main body of Volunteers and ICA members marched more conventionally from Liberty Hall. Seán T. O’Kelly, who was with them, watched the windows of the GPO being broken by Diarmuid Lynch, at James Connolly’s instruction, and realized the long-awaited rebellion ‘was an accomplished fact’.14 The occupation of the Post Office, a splendid neoclassical edifice recently restored, would become an iconic moment in Irish history, and the noble Grecian building provided an appropriate locale for the declaration of a republic.

Simultaneously, other buildings were seized. These were an odd choice in some ways, including Boland’s Mill, Jacob’s Biscuit Factory and the South Dublin Union (a complex of buildings dispensing poor relief, which amounted to a small village in themselves). The Shelbourne Hotel was left to the enemy, which made the occupation of Stephen’s Green – the park in front of it – something of an own-goal. While a cursory attempt was made on Dublin Castle, the concentrated effort in the area was focused on the adjoining City Hall, from which the rebels were expelled within twenty-four hours. Other prominent buildings, which had been closely reconnoitred on marches and exercises the year before, were surprisingly ignored. Some of the most successful engagements, such as the killing rectangle set up by rebel snipers at Mount Street Bridge, which trapped waves of troops advancing down Northumberland Road, or the punishing engagement at Ashbourne Barracks stage-managed by Richard Mulcahy and Thomas Ashe, were no part of a pre-arranged ‘clockwork’ plan.

Hostilities were opened with an odd combination of chaos and effectiveness, and this approach dominated events throughout the week. Improvisation was the order of the day, along with the surreal effects of unexpected war in the centre of a large city: toy-shops exploding with fireworks, looters from the slums (adjacent to the fiercest fighting) prancing through the bullets arrayed in their finery, garrisons living off odd combinations of food sourced from commandeered premises, excited crowds thronging to spectator-points and keeping up a running commentary. But this was just the background to the reality of killing, in a savage episode of warfare that involved lethal hails of sniper-fire, machine-guns and field artillery, and eventually a gunboat on the Liffey blasting away at rebel strongholds. When it was all over, the area around Sackville Street resembled – as many observers remarked in awestruck tones – the shelled remains of Louvain, Amiens or Ypres. A favourite subject for souvenir photographers was the dramatically gaunt shell of the bombed-out DBC Café, where Mary Kate Ryan had held court in days gone by.

Within the rebel fortresses, the mood varied. In the GPO a certain elation was sustained, encouraged by Pearse’s ecstatic but delusive communiqués about the country rising as one to the republican cause and German landings everywhere. Min Ryan cornered Tom Clarke in the GPO kitchens on the Tuesday night and extracted a more reasoned view. ‘He . . . said that at all periods in the history of Ireland the shedding of blood had always succeeded in raising the spirit and morale of the people. He said that our only chance was to make ourselves felt by an armed rebellion. “Of course,” he added, “we shall all be wiped out.” He said this almost with gaiety. He had got into the one thing he had wanted to do during his whole lifetime.’15 Clarke, a veteran of earlier struggles and imprisonment, spoke for a different generation; Min privately remembered, years later, her shock when she realized the inevitable end for most of the young rebels, including her sweetheart Seán MacDermott. By now unofficially engaged, they had last seen each other in the Red Bank restaurant on Good Friday. As it was a fast day, she had been surprised and rather disapproving to find him ordering a large steak. But he had left the rural pieties of his youth far behind him, and he knew he was going to need it.16

For others, the atmosphere of elation, and the conquest of fear, was sustained by an intensely religious atmosphere. Before going out to storm the city, whole battalions of Volunteers had taken Communion, in a spirit of solemn exaltation. During the occupation of the GPO the Rosary was said communally every night, and priests were on hand to hear confessions, despite the Church’s extremely ambiguous view of the whole venture. (Some locations of worship were unconventional: in Boland’s Mill a bread-van served as an impromptu confession-box.) Even anti-clerical Fenians like John MacBride, and people of unconventional or agnostic beliefs like Thomas MacDonagh and James Connolly, seem to have rapidly been affected. This confounding of Catholicism with the rebel cause would be of immense importance as the war gathered momentum in the ensuing months.

Another indication for the future might be seen in the attitudes towards women rebels. Some, notably Constance Markievicz, wielded guns, and Sheila Humphreys shocked her sister by her ‘inhuman’ delight in taking pot-shots at the enemy.17 But, generally, women’s roles were kept ancillary: cooking, nursing and carrying messages, often at immense personal risk. Phyllis Ryan’s memory of her time in the GPO was dominated by endlessly carving sides of beef liberated from the neighbouring Metropole and Imperial hotels. Even members of the paramilitary Cumann na mBan, however much they argued for taking their place in the front line, were treated as helpmeets rather than as fellow soldiers.

Patriarchal attitudes were probably reinforced by the sheer bloodiness of the carnage in areas of close engagement, the horrific mutilations wreaked by gunfire, shells and grenades exploding in confined spaces, and the terrible toll taken of civilian as well as of combatant lives. This was particularly the case around Sackville Street, and in the hinterland behind the Four Courts, where savage fighting took place in narrow commercial and residential streets. Here the 25-year-old Ned Daly, Kathleen Clarke’s brother, emerged as one of the most competent insurgent leaders, wreaking considerable devastation on British forces, which culminated in a savage pitched battle over the barricades in North King Street. Daly’s young age was representative: all the Volunteers (except one) occupying the hard-fought fortress of the Mendicity Institute on the quays, commanded by the 25-year-old Seán Heuston, were aged between eighteen and twenty-five. Observers constantly reiterate the extreme youth of the combatants; several Volunteer commanders tried to send their most enthusiastic teenaged followers back home, with varying success.

Among the rebels, inexperience was compounded by the nature of their weaponry: the ‘Howth Mausers’ dating from the great gun-running kicked like a mule, and the cocoa-tin bombs manufactured at Larkfield could be lethally unpredictable. Many of their military opponents, if better armed, were almost as inexperienced and disorientated; there is much evidence of traumatic reactions to the carnage, desertions of posts and loss of control among British Army units.18 Among Volunteer battalion commanders, both MacDonagh and de Valera came near to cracking up completely. But other commanders – perhaps less intellectually sensitive – found their métier, emerging as dynamic and effective soldiers, and fully relishing the excitement, unpredictability and violence of the extraordinary situation which they had precipitated. Several, such as Ned Daly and Seán Heuston, would not survive the Rising and its aftermath. Others, such as Richard Mulcahy, Cathal Brugha and Oscar Traynor, would use these latent abilities in a longer war. A new ruthlessness would characterize the ‘gunmen’ in whose hands the prosecution of revolutionary action now rested.

The exhilaration experienced by some was intensified by the theatricality of the whole affair. The insurgents kept a close eye on opportunities to historicize the event in the making: above all the reading of the ‘Proclamation of the Irish Republic’ outside the GPO and the running up of a revolutionary tricolour above the building, accompanied by a green-and-gold banner bearing a harp, designed hastily by Constance Markievicz. The Citizen Army flag, depicting a worker’s plough traced out in stars, was flown from the adjacent Metropole Hotel. This was the property of William Martin Murphy, perceived since the 1913 lockout as the arch-enemy of Dublin’s proletariat – another poignant symbol of the world turned upside down. It has been suggested that the targeting of Jacob’s Biscuit Factory and the South Dublin Union may also have been dictated by their symbolic value, as both had featured heavily in socialist campaigns against injustice and exploitation; but without solid evidence of the rebels’ general plan, it is impossible to say.19

While witnesses of Pearse’s reading of the ‘Proclamation’ after noon on Easter Monday more or less agree that the effect was perfunctory, the echoes resound still. The ‘Proclamation’ itself distilled Pearse’s own idea of an apostolic succession of nationalist struggles into what has been memorably described as ‘a kind of national poem: lucid, terse and strangely moving even to unbelievers’.20 The promises of ‘religious and civil liberty, equal rights and equal opportunities to all its citizens’, cherishing ‘all the children of the nation equally . . . oblivious of the differences carefully fostered by an alien government’, suggested a radical tolerance which would remain a matter of aspiration for the future. It was also a rather airy rationalization of Ulster’s resistance to Irish nationalism. More to the moment, the reference to Ireland’s ‘gallant allies in Europe’ meant, as Cesca Trench at once noted, that charges of high treason would inevitably be levelled in the fullness of time.21

Pearse’s emergence as supremo of the ‘Army of the Irish Republic’ (as the Volunteers and their insurrectionary allies were beginning to be called), and President of the Provisional government, was an unexpected development for this recent IRB recruit. Seen by many as erratic, unstable and (in Hobson’s word) ‘abnormal’, his elevation infuriated Kathleen Clarke in particular, since she felt – not unreasonably – that her husband, Tom, was ipso facto President from his senior position within the IRB. But Pearse’s identification with the ‘Proclamation’, his rhetorical power and the carefully constructed literary inheritance which he left combined to propel him to the forefront. His Old Testament-style fulminations against Redmond and the Home Rulers had reached apocalyptic levels just before the Rising: ‘[they] have done evil and they are bankrupt . . . When they speak they speak only untruth and blasphemy. Their utterances are no longer the utterances of men. They are the mumblings and the gibberings of lost souls.’22 This view of the desperate attempts of Redmond and his lieutenants to negotiate a Home Rule settlement around the Ulster impasse would soon become received wisdom. And the Rising became identified with Pearse’s particular ideology of blood-sacrifice and mystical Catholicism. This not only dismissed the real issues of a divided island headed towards civil war or partition, but misrepresented or played down the several streams which had contributed to the revolutionary mentality.

III

The extraordinary and transfigured atmosphere of life within the rebel strongholds during the week that began on Easter Monday 1916 has been evoked in numerous sources. With the release of the Bureau of Military History witness statements, the volume of material has become overwhelming, and in recent years has been distilled into several classic accounts.23 The individual experiences of many of the revolutionary generation during this apotheosis are enshrined for posterity, though some key figures did not leave their testaments, either because they disagreed with the whole enterprise (and refused to recognize the authority of the government trying to implement it), or because they did not survive to tell their tale. From the glimpses and memories recorded by others, the moods of Pearse, Connolly, MacDermott and Clarke within the GPO, and Markievicz at the College of Surgeons, were to varying degrees elated, punctuated by realistic episodes of recognition that they were, or would be, defeated.

For Joseph Plunkett and his siblings, the dreams of their rebellious youth had at last taken solid form. His own romance with Grace Gifford had developed apace with the blueprint for insurrection; they had planned a double wedding for Easter Sunday with his sister Geraldine and Thomas Dillon (despite Geraldine’s powerful aversion to Grace), but this can only have been a diversionary tactic. One of his last love-letters to Grace, two days before the Rising began, sums up the mood of the moment:

Holy Saturday 1916

My Darling Sweetheart,

I got your dear letter by luck as I was going out at 9 this morning and have not a minute to collect my thoughts since now 2.45 p.m. I am writing this at above address. Here is a little gun which should only be used to protect yourself. To fire it push up the small bar under the word ‘Safe’ and pull the trigger – but not unless you mean to shoot. Here is some money for you too and all my love forever.

Xxxxxxxxxxxx Joe xxx24

They would meet again the night before his execution, for their postponed marriage. Also active in Easter Week were the Plunkett brothers, George (who conducted the Larkfield ‘lambs’ by tram to the revolution) and Jack, while Geraldine rather frustratedly tried to play a part on the sidelines. Their sister Mimi had acted as courier to John Devoy and Clan na Gael in New York in the frantic weeks before the Rising, but she too stayed out of the action. After the Rising, their ineffective dilettante father Count Plunkett would briefly find himself catapulted into a symbolic leading role, and even their hated mother became an agitator for prisoners’ relief and other republican causes.

Plunkett’s friend and fellow poet Thomas MacDonagh, a late recruit to the Military Council (where his chief function was to lull his friend and university colleague MacNeill into a false security), was also a signatory of the ‘Proclamation’. ‘A man who is a mere author is nothing,’ he had decided. ‘I am going to live things that I have before imagined.’25 He would become one of the canonized leaders of the rebellion, but his experience at Jacob’s Biscuit Factory, which saw little military action, was less fulfilling. His own insecure, febrile and intermittently gloomy temperament had propelled him into an emotional state even before the upheavals of the Easter weekend (during Holy Week he had been notably indiscreet about the approaching event, as was recorded by a police spy whose evidence was breezily ignored by the Castle).26 The British forces decided the Jacob’s fortress did not merit a frontal assault, but they unnerved its occupants by buzzing it with occasional sniper-attacks and creating a diversionary racket outside the building at unexpected hours of the night. Sleep deprivation, isolation from other spheres of insurrectionary activity, and possibly the unrelieved diet of cake and biscuits made MacDonagh an erratic leader; much of the initiative passed to Major John MacBride, Maud Gonne’s estranged husband, who had joined the rebellion by chance and was still wearing the smart blue suit in which he had set out on Monday to be best man at his brother’s wedding. When the inevitable surrender came, MacDonagh’s behaviour was irrational in the extreme, and the garrison began to dissolve into chaos. It was pulled back from the brink by MacBride’s sensible advice to obey Pearse’s order, to take the chance of liberty if they could, and to ‘never allow yourselves to be cooped up inside the walls of a building again’.27

This and much else was recorded by the actress and activist Máire nic Shiubhlaigh, who had once created an unforgettable impression in The Shuiler’s Child for the Theatre of Ireland, and was now acting as a cook in the kitchens of the occupied biscuit factory. Other veterans of agit-prop drama played a part on the stage of the Rising, including Constance Markievicz, Helena Molony, Máire’s brother Frank and the glamorous actor Seán Connolly. Connolly was responsible for the first fatality (shooting a policeman outside Dublin Castle) and was later himself killed by sniper-fire on the roof of the City Hall. Markievicz was widely noted by the spectators, marching around Stephen’s Green in a feathered hat and a characteristically outré uniform; she had apparently arrived there more or less by chance, and been appointed Second-in-Command by the rather irresolute Citizen Army Commandant Michael Mallin. Another thespian, Piaras Béaslaí, had taken a leading part in the Volunteers’ split from Redmond and now emerged as Vice-Commandant of the 1st Dublin Battalion at the Four Courts, from where he saw a fair amount of action in Blackhall Street. Unrealistically averse to surrendering, ‘he scoffed at the idea, pointing out that the position was “impregnable and could be held for a month”.’28 This reluctance may reflect the dreams he had confided long before to his diary when he was a discontented youth in bourgeois Liverpool, longing for nothing more than to make a mark in the world, fighting for Ireland.

The Ryan sisters and their circle were also centrally involved. Seán T. O’Kelly, as an influential IRB fixer, had been privy to the frenetic comings and goings in the days before, including several pivotal meetings when the conspirators were trying to keep MacNeill on board. Not a fighting man, O’Kelly’s own experience of the military side of events was as aide-de-camp to Pearse. He had marched to the GPO from Liberty Hall with Pearse and Connolly on Easter Monday morning, supervised the running up of the flags bearing the tricolour and the harp, and posted 200 copies of the ‘Proclamation’, secured by flour paste, around the city centre. The more militant Richard Mulcahy found himself, with the charismatic but less practical Thomas Ashe, conducting effective guerrilla actions against police forces around the villages north of the city, where Volunteers and Fianna training in fieldcraft came into its own. The coolness and strategic brio which Mulcahy displayed marked him for a career as an army supremo that would stretch far into the post-revolutionary dispensation. Min and Phyllis Ryan were stationed, through their own determination, in the GPO, and undertook hair-raising courier missions through the gunfire. (These included taking a message from Pearse to his mother out in Ranelagh, which cannot have carried a high military priority.) Madeleine ffrench-Mullen played a similar role, while her partner Kathleen Lynn ran an effective field hospital; the Ryans’ medical-student brother James also used his expertise to good effect, tending the injured James Connolly in the GPO and accompanying the insurgents in their terrible retreat to the warren of houses around Moore Street – the withdrawal in which Michael O’Rahilly, who had tried to stop the Rising but turned up to join in when it took place, met a brave death under fire.

Some, later to be celebrated as freedom fighters, took part on the spur of the moment: most famously the eighteen-year-old Ernie O’Malley, just beginning his studies in medicine, and ignorant up to then of much that was going on around him. Previously he had followed the tendency of his well-off family to jeer good-naturedly at the pretensions of the Volunteers; but in Easter week he became swiftly radicalized, borrowed a rifle and took part in some amateur sniping. O’Malley personified one portent for the future. Another was represented by Joe Plunkett’s secretary from Larkfield, a handsome 26-year-old Corkman called Michael Collins, who ended up in the GPO, where he viewed the delusional bravado of his seniors with an impatience bordering on contempt. Clever, convivial and frighteningly single-minded, Collins had begun a successful career in London (Post Office, stock exchange clerk, Board of Trade); he was one of many rebel combatants who had returned to Ireland from Britain after the outbreak of war and thrown themselves into the radical-nationalist movement. Art Ó Briain, indefatigable organizer of radical Irish movements in London, later drew up an evocative list of ‘London Gaels who lost their lives in Easter Rising 1916’. Patrick Shortes, born in 1893 in Ballybunion, studied as a scholarship boy at St Brendan’s Seminary, Killarney, then All Hallows, Dublin, and a B.A. at UCD; he gave up his vocation and became a wireless operator until refused a licence in London due to political activities. Shortes had returned to Dublin in early 1916, as had Seán Hurley, originally of Clonakilty. Older London-Irish combatants included Michael Mulvihill, born in 1880 in Ballyduff, who, like Collins, did his civil service exams and entered the Post Office; he had joined the Gaelic League and Volunteers in London, returned to Dublin on Easter Sunday and met his death on the roof of the GPO. Patrick O’Connor, another Kerryman, born in 1882, had won the first place in the United Kingdom in the civil service exams and entered – inevitably – the Post Office service in 1900. He returned to Ireland twelve years later, and went to the GPO on Easter Monday night. Other Kerrymen who had worked in the postal services in London, joined the Gaelic League and GAA there, and returned to Dublin to fight included Tom O’Donoghue and Denis Daly, both originally from Cahirciveen; they both survived. Ó Briain also lists Donal Sheehan and Con Keating, two of the revolutionaries who were killed outside Killorglin on Easter Saturday, when their car took a wrong turning and plunged into the River Laune, on their way to commandeer the wireless station at Cahirciveen. They too had been radicalized through Gaelic League circles in London. Ó Briain’s list sketches the kind of networks which stretched from the remote south-west of Ireland to the Irish-Irelander circles of Edwardian London, via the imperial structure of the Royal Mail, creating an unexpected but recognizable pattern of radicalization.29

IV

Outside the rebel redoubts ringing the city centre, several prominent figures of the revolutionary generation watched impotently, or tried to make their own contribution. Francis Sheehy-Skeffington had taken a leading part in opposing the war effort, campaigning against recruitment and arguing that Ireland should have remained neutral. His reasons were pacifist rather than nationalist, though the distinction was ignored by the authorities; he had made what were considered incendiary speeches, been arrested and gone on hunger-strike, and subsequently campaigned in America.30 When the Rising broke out, he set himself to patrolling the streets, trying to stop looting; this led to his being apprehended by a homicidal British Army officer called Captain J. C. Bowen-Colthurst, who had him summarily executed, along with two other journalists, in Portobello Barracks.

The circumstances of the murder reflected the hysteria of the times (Bowen-Colthurst had already shot dead a defenceless youth called J. J. Coade along the way), but the authorities’ attempts at a cover-up afterwards compounded what became seen as one of the most damaging episodes of British oppression in Ireland. The exposure and subsequent trial of Bowen-Colthurst only came about through the efforts of a fellow officer, Major Sir Francis Vane (who did not win much official approval for it). Moreover, by tricks of legal chicanery at the highest level, Bowen-Colthurst was tried by court martial rather than in the civil courts, the latter course having been relentlessly blocked. Judged ‘guilty but insane’, he served a few years’ incarceration in Broadmoor and emigrated to Canada. The choice of victim could not have made worse publicity for the authorities. Sheehy-Skeffington’s energy, charm, high principles, mild eccentricity and commitment to pacifism, egalitarianism and feminism had made him a central figure in Dublin’s radical intelligentsia since his student days; his wife, Hanna, was not only an influential activist but a member of the powerfully connected Sheehy family (soon to be seen as part of the constitutional-nationalist ancien régime but still to be reckoned with). Her unremitting campaign against the British government, which included successful lecture-tours throughout the USA, was effective far outside Ireland.

Other vital figures from the pre-revolutionary dispensation sat on the sidelines, usually because they had opposed the whole affair – above all Eoin MacNeill, the deceived commander of the Volunteers. Early on Easter Monday afternoon, as he was cycling down Rathgar Road with Seán Fitzgibbon, they met their fellow Volunteer Liam Ó Briain; information was exchanged, and after a reconnoitre Fitzgibbon and Ó Briain confirmed that hostilities had begun. After raging at his betrayal by Pearse, MacNeill declared his intention to join the rebels, but in the event went home to Rathfarnham and stayed there. Arthur Griffith, who had done so much to influence so many of the rebels, was equally inactive, for reasons that remain obscure. The moderation of his nationalist strategy in the pre-war years was not forgotten, and he had not been in the confidence of the leaders. Nonetheless, observers would almost at once christen the Rising a ‘Sinn Féin rebellion’, and the aftermath would see yet another transformation in his position, and that of the uncertain political coalition which he had created.

Another figure, almost equally influential in the inspiration of a revolutionary generation, was sidelined for good. This was Bulmer Hobson, who on Good Friday was effectively kidnapped by the extremists and imprisoned in Martin Conlan’s house in Cabra, before he could do any more damage (as they saw it). This came almost as a relief. ‘I felt that I had done all I could to keep the Volunteers on the course which I believed essential for their success,’ he later recalled, ‘and that there was nothing further I could do . . . I had been working under great pressure for a long time and was very tired. Now events were out of my hands.’31 He may have felt less philosophical at the time. On Easter Monday night, Seán T. O’Kelly was dispatched to release Hobson, finding him bad-temperedly reading a book under armed guard. As they walked back towards the city centre, with gunfire echoing in the background, O’Kelly later claimed he tried to persuade the reluctant Hobson to join the battle for which he had spent so much of his life preparing, and which he had done so much to bring about. Eventually Hobson said he would go home, fetch his rifle and find his Volunteers detachment, but this seems to have been simply a stratagem to get rid of the importunate O’Kelly. They shook hands by the canal and parted. Hobson walked home, and out of history. Like MacNeill, he stayed inside for the rest of the week, nursing a sense of betrayal. Unlike MacNeill, he would never return to the political stage.32

Hobson’s friend and patron Roger Casement was equally opposed to mounting a rising in the way that it fell out, and had travelled to Ireland to try to put a stop to it; but this would not be remembered as part of the myth already gathering around him. For Casement himself, his extraordinary return by U-boat, eventually washing up on Banna Strand in a collapsible dinghy, marked a kind of epiphany. Ill, exhausted, deeply disillusioned with his idealized Germans, he later remembered lying in the sand dunes listening to birdsong and feeling calm and happy for the first time in years.

Although I knew that this fate waited on me, I was for one brief spell happy and smiling once more. I cannot tell you what I felt. The sandhills were full of skylarks, rising in the dawn, the first I had heard for years – the first sound I heard through the surf was their song as I waded in through the breakers, and they kept rising all the time up to the old rath at Currahane where I stayed and sent the others on, and all round were primroses and wild violets and the singing of skylarks in the air, and I was back in Ireland again.33

The adversity that had marked this stage of his life – his ineffectual negotiations in America and Germany, his plunge into depression, the betrayals and inept conspiracies which bedevilled him, and the pressures of his driven and contradictory private life – seemed to vanish. Like Pearse 200 miles away in the GPO, he was embarked on a Christological journey to martyrdom, and into the canon of Irish nationalist sainthood. Ardfert Police Station was the beginning of his road to Calvary.

Thanks to MacNeill’s countermanding order, the confusion that bedevilled the Kerry Volunteers was reflected elsewhere in Ireland, leaving other revolutionaries marooned or inactive. Denis McCullough, titular President of the IRB Supreme Council, remained in Belfast. Here the anti-Redmond Volunteers were a rather sketchy presence, given the power of Joe Devlin’s Hibernian network. Both McCullough, as Commander in Belfast, and his friend Pat McCartan, in charge of the Tyrone Volunteers, found their forces resistant to the orders that came from Dublin; this was unsurprising, since Pearse’s idea was that they should march south-west towards Galway to ‘hold the line of the Shannon’, a manoeuvre that would take them through redoubtable unionist and Protestant heartlands, with the inevitable result of ambushes by the UVF. Discipline was already collapsing among the men gathered at Coalisland when the countermanding order arrived to undercut the commanders’ plans completely. After chapters of accidents and confusions (McCullough at one point literally shot himself in the foot), the Volunteers returned by train to Belfast, McCullough paying their fares. There they disbanded, disconsolate.

The Galway forces were better prepared under Liam Mellows, but, though he managed a more decisive mobilization, the failure of arms to arrive and the early notification of the local authorities stymied an effective display of force. The same story was true all over Ireland.34 The general confusion and inactivity in the provinces would have a potent effect on revolutionary mentality after the Rising; as the Dublin insurrection passed into myth, a powerful sense of guilt was exploited by provincial leaders, determined to expiate their record during Easter 1916. (Paradoxically, they would eventually do so by adopting the tactics of country-wide guerrilla disruption advocated by Bulmer Hobson, though nobody gave him credit at the time or afterwards.)

Nowhere was this sense of shame following a missed chance of martyrdom more potent than in Cork. Liam de Róiste, so indefatigable in organizing and consciousness-raising for so many years, had moved into the Volunteers headquarters at Sheares Street for Holy Week, awaiting orders. Instead, he and Tomás MacCurtain received on Saturday the shocking news of Casement’s arrest, brought by a courier from Kerry. Nonetheless, on Sunday they prepared for significant action, distributing first-aid outfits along with weaponry, and putting a force of 154 Volunteers on the train from Cork to Crookstown, while others set off by bicycle. The plan was to meet other forces (to a total of about 1,200 men) at various points in the west of the county. At this point James Ryan arrived in the city with MacNeill’s countermanding order, so MacCurtain and MacSwiney intercepted the force at Crookstown and cancelled their mobilization orders.35 Confusion was compounded by Marie Perolz arriving with contradictory orders from Pearse (the first of a blizzard of dispatches to hit Cork).

Irresolution reigned among the leaders, who from Monday sat and waited in Sheares Street; a rumour that the Dublin disturbance was simply an uprising by the Citizen Army, which Mary MacSwiney dismissed as a ‘rabble’, acted as a further disincentive to action. To the annoyance of many rank-and-file Cork Volunteers (more numerous and better prepared, armed and drilled than in most provincial centres), the brigade commanders remained undecided. To angry emissaries from the beleaguered capital, such as Nora Daly, ‘they both seemed to think Dublin was wrong and they were right. They said they had documents to prove they were right.’36 At the end of the week, a bizarre and obscure deal was arranged via the Lord Mayor and local clerics whereby the Volunteers’ guns were to be given up but not impounded by government forces; arrests and seizures of arms nonetheless followed, exacerbating the general ill-feeling.

Above all Terence MacSwiney was struck by an immediate and abiding sense of failure. Since his boyhood he had been confiding to his diary dreams of martial glory and bloodthirsty vows against the Saxon, but when the call came he spent the week dithering indoors and reading Thomas à Kempis’s Imitation of Christ. As the epic nature of the Dublin insurrection became known, his and MacCurtain’s private opinion that ‘the Dublin crowd were daft’37 changed to a determination to equal their sacrifice. Their friend and fellow Cork revolutionary, P. S. O’Hegarty, was out of Ireland during the Rising, having been transferred to Welshpool by his Post Office employers (they may have finally realized just how little work he did in office hours). Seán MacDermott visited him in May 1915, as an emissary of the IRB, and outlined the plans for a rising – much as they were to happen a year later.38 Perhaps because of his distance from the scene of action, not to mention his distaste for religion, O’Hegarty retained a detached attitude towards sacrificial violence, an agnostic approach to the excesses of devotional martyrology, and a belief that the spectacular gesture of 1916 should pave the way for a political transformation, rather than sounding the trumpet for a campaign of war. He was not alone in this, but MacSwiney’s priorities would carry the day.

Apart from Cork, the county that might have been expected to rise, given the weight of history attached to it, was Wexford. There was a well-established revolutionary nexus in the county: not only the Ryan siblings and their followers, but Robert Brennan, the journalists Seán Etchingham and Larry de Lacey, and a strong IRB circle. The Enniscorthy Echo was a notably nationalist paper, advancing Sinn Féin ideas from an early stage, and supporting the Volunteers, whose local journal was printed at their offices; the radical IRB man Seán O’Hegarty (brother of P. S.), who also worked for the Echo, was arrested for seditious pro-German propaganda. However, Wexford was also home to John Redmond, to the influential Esmonde family (Catholic gentry nationalists) and a solid Irish Parliamentary Party elite; in 1916 the county town remained quiescent and supportive of the authorities (to the contempt of the Ryan family). Neighbouring Enniscorthy saw more action than many places, involving the holy ground of Vinegar Hill, scene of a last rebel stand in 1798. When the rebels actually seized the town on the Thursday after Easter, some of them were even armed with pikes. They held out for four days, instituting a virtual republican administration, including a police force, and raising many new recruits. But the local barracks remained in RIC hands, and the constabulary regained control by the end of the weekend, leaving the memory of a symbolic victory. As in Dublin, the possibility of rebellion had become more than a chimera, and this would create a lasting impression.39

V

By the Friday after Easter Monday, the storm-centres of the Rising in Dublin were erupting into a spectacular Götterdämmerung. Whole buildings were ablaze, with the shop-windows of Sackville Street running as molten glass on to the pavements, and the shelling and gunfire were relentless. The doomed central garrison eventually fought its way through the little streets behind the GPO, loopholing their course from house to house. The ignition of an oil depot in Abbey Street completed the inferno, ‘a solid sheet of blinding, death-white flame rushes hundreds of feet into the air with a thunderous explosion’.40 One Volunteer enterprisingly telephoned the fire brigade from within the GPO, only to be crisply told that they were to be left to be burned out. Others reacted differently, glorying in the destruction; for many the circle of fire, while spelling the beginning of the end, also confirmed the impact of their insurrection.

This was evidenced in more than the million pounds’ worth of damage to buildings on Sackville Street. When it was all over 450 people in total had been killed, 2,614 wounded, 9 missing; of those, 116 soldiers had been killed, 368 wounded and 9 missing, along with 16 policemen dead and 29 wounded. Out of 1,558 combatant insurgents, 64 rebels had died.41 The toll of civilians was surprisingly and, to some, shockingly high. Throughout the battle-zones, the bodies of people and animals had lain rotting in the unseasonably warm weather, and subsequently been buried rapidly in odd places. The buildings went on smoking and collapsing for days.

The decision to surrender was taken by the leaders in a house in Moore Street around midday on the Saturday, and carried by Nurse Elizabeth O’Farrell (under constant threat of gunfire) to Brigadier-General W. H. M. Lowe. As the news spread to other outposts it was received in some quarters with disgruntlement and even anger. But the outcome was strongly defended by Seán MacDermott and others, stressing their status as prisoners-of-war and arguing that, though the leaders would no doubt be shot, the rank-and-file would eventually be released to continue the struggle: and that, above all, the inspirational and radicalizing effect of their revolutionary gesture would endure. In the circumstances of their defeat and capture, the rebels were determined to present themselves as soldiers who had fought a clean fight. Most indeed managed to do so, in a manner that impressed many of their opponents, and this too would contribute powerfully to the revolutionary myth. Numerous accounts of chivalrous and ‘gentlemanly’ behaviour were broadcast, sometimes from British Army personnel who had been captured or otherwise dealt directly with insurgents. After the surrender, though some thuggish and sadistic behaviour is recorded, relations between the soldiers and their captives often showed a marked degree of respect.42 There had been some shooting of unarmed targets, and evidence that the rebels used soft-nosed bullets to terrible effect, but the overall impression created by the rebel army was that they had fought with discipline as well as valour.

This helped to obscure the chaotic, amateurish and contradictory manner in which the insurrection had begun; it would also, in time, weight opinion heavily on the side of those who had actively embraced it, rather than on their more cautious comrades. As it was, general opinion (especially in Dublin) seems initially to have condemned the Rising as an act of destructive madness; famously, the captured rebels were abused by Dublin crowds as they were led through the streets. But this was particularly true in Protestant working-class areas, and other sectors where men were away fighting at the Front. There is also much anecdotal evidence of isolated expressions of support, and more thoughtful observers noted a groundswell of fellow feeling among elements of the populace who claimed they would have supported the rebels, if they had had a chance. An underlying sympathy among many observers was noted by Major Henry de Courcy-Wheeler, the astute Anglo-Irish Army officer who witnessed Pearse’s surrender. As Ceannt’s and de Valera’s forces left the South Dublin Union and Boland’s Mill respectively, they were cheered by the local populace; and there is much anecdotal evidence of support from priests and nuns, whatever line their senior colleagues might have taken in public.

Those who were probably furthest from feeling sympathy were members and supporters of the Irish Parliamentary Party, since the conclusion rapidly reached by politically minded observers was that this extraordinary event would banish hopes of Home Rule – and certainly the already faint hope of a Home Rule Ireland which could include Ulster. The record of Redmond and his colleagues, so recently presented as the men who had brought Parnell’s dream into reality, was rapidly effaced. One sharp-eyed English visitor, joining the spectators to watch Dublin go up in flames, realized that it was ‘much more than the burning of a city – it means the ruin of a cause, the grave of a hope, the dissipation, perhaps for many years, of a great political dream’.43

By the time of the surrender, Dublin was under the military rule of General Sir John Maxwell, who had superseded Lowe on 28 April, having been sent expressly by Asquith. Maxwell saw his task as the repressive restoration of order, and the meting out of the ultimate penalty – after brief court martial trials – to the leaders of the insurrection. This was no more than the rebels expected. From Richmond Prison Seán T managed a brief note to Mary Kate, reporting a conversation with MacDermott on his way to trial. ‘I am afraid his chances of escaping the final penalty are small. He was however in the best of spirits. He doubtless fully realises the peril of his position.’44 This was true of all the leaders, who almost universally preserved a transfigured and defiant attitude, in the best traditions of national martyrs. A note of tragic romance was supplied by Joseph Plunkett’s marriage to Grace Gifford the night before his execution, leaving her as an awkward bequest to his hostile family. The wedding, held late at night, was brief; later they were allowed a ten-minute meeting in a cell packed with observers, and she left dazed. ‘We who had never had enough time to say what we wanted to each other found that in that last ten minutes we couldn’t talk at all.’45 The soldier attending them left his own version. ‘I brought the priest and the girl into the prison and when I took her out she was quite cheerful like, and she looked around and said, “This isn’t such a gloomy place as I thought it was.” She was a cool one.’ 46 Overall, a dignified and philosophical acceptance of their fate, ‘carefully choreographed by their leaders, exerted a greater emotional charge than the six days of scrappy fighting that preceded it’.47 The focus accordingly shifted to the manner in which the authorities had reacted; and they would play their pre-ordained part with militaristic obtuseness and heavy-handed coercion. Both sides colluded in the making of martyrs.

After being held, often in makeshift conditions that were appallingly basic and insanitary, a good many ex-combatants were released – especially teenaged boys and women, seen as particularly troublesome prisoners. Incarceration together at Richmond Barracks enabled the leaders to keep up their esprit de corps. Apart from the signatories of the ‘Proclamation’, who seem generally to have accepted that they were doomed to the penalty for treason, several hoped that internment would enable them to regroup and fight another day, as would indeed be the case. Political imprisonment had a long and respected history in Ireland, and traditionally formed the foundation of many political careers. Given the pressures attendant upon prosecution procedures, internment was often adopted as an easier option; the legal proceedings that did take place often followed an uncertain course and were ridiculed by those on trial. Behind the scenes, Redmond, Dillon and other Irish MPs argued desperately for leniency towards the rebels, anticipating the consequences of creating martyrs. While some death sentences were handed down to secondary leaders such as Harry Boland, they were often commuted to imprisonment. For Eoin MacNeill and Arthur Griffith, arrest, trial and imprisonment came as a serendipitous chance of reintegration into advanced-nationalist circles. But MacNeill, whose defence at his trial rested on his strong repudiation of armed insurrection, remained an object of hatred for many who had fought.48

For the signatories of the ‘Proclamation’ and other prominent leaders, the result of their trials for fomenting insurrection with foreign aid at a time of war was a foregone conclusion, and the sentences of death were not commuted. They were tried, rather questionably, under the wartime Defence of the Realm Regulations by field courts martial. The executions between 3 and 12 May of Patrick and Willie Pearse, James Connolly, Thomas MacDonagh, Joseph Plunkett, Éamonn Ceannt, Seán MacDermott, Tom Clarke, Ned Daly, John MacBride, Michael Mallin, Seán Heuston, Con Colbert, Michael O’Hanrahan and Thomas Kent were followed by the hanging of Roger Casement at Pentonville on 3 August. Most of the leaders, while they pleaded not guilty, did so because they denied that they owed allegiance to the government and were not, therefore, committing treason. A few argued against the evidence produced, and Mallin tried to claim that he was under Markievicz’s command, rather than the other way round. Markievicz herself escaped execution, as did de Valera, Ashe and Mulcahy, despite their prominent combatant roles; by 9 May, according to Maxwell, the government was leaning heavily towards moderating death sentences.49

Over the summer, a powerful campaign had got under way arguing clemency for Casement and a commutation of the death sentence; this was opposed behind the scenes by circulation of extracts from his sexually explicit diaries, which had been seized from his London lodgings. Casement, like several other revolutionary leaders, used his trial to produce a stirring testament firmly rooted in the established convention of a nationalist conversion-narrative, and dismissing the claim that his activities in Germany should be considered treasonable. He returned to the question of the Ulster Volunteer Force, its defiance of the law, and the answering gesture of the Irish Volunteers. ‘The difference between us was that the Unionist champions chose a path they felt would lead to the woolsack [F. E. Smith had become Lord Chancellor]; while I went a road I knew must lead to the dock. And the event proves we were both right.’ As for his companions in the revolutionary movement, their actions showed the irrelevance of Home Rule compared with true independence. ‘If we are to be indicted as criminals, to be shot as murderers, to be imprisoned as convicts because our offence is that we love Ireland more than we value our lives, then I know not what virtue resides in any offer of self-government held out to brave men on such terms.’ Privately, he was less controlled, and a late letter to his sister conveys something of his state of mind:

If I could only tell you the whole story, but that too is part of my punishment – of the strange inscrutable fate that has come to me – that I am not only being put to death in the body but that I am dead before I die – and have to be silent and silent just as if I were already dead – when a few words might save my life – and would certainly change men’s view of my actions. Long ago, years ago, I wrote these lines of another – but they are my own – my epitaph on my own fate perhaps more than on that of the man I penned them of: ‘In the mystery of transgression is a cloud that shadows Day, For the night to turn to Fire – showing Death’s redeeming way.’50

Pearse’s statement at his trial was unequivocally dramatic and effective.

When I was a child of ten I went down on my bare knees by my bedside one night and promised God that I should devote my life to an effort to free my country. I have kept that promise. As a boy and man I have worked for Irish freedom, first among all earthly things. I have helped to organise, to arm, to train and to discipline my fellow countrymen to the sole end that, when the time came, they might fight for Irish freedom. The time, as it seemed to me, did come, and we went into the fight. I am glad we did. We seem to have lost. We have not lost. To refuse to fight would have been to lose; to fight is to win. We have kept faith with the past, and handed on a tradition to the future.51

Others, such as MacDonagh, had equally high-flown speeches posthumously invented for them. Many testaments were left behind, ostensibly as letters to wife and family, but also aimed at a wider audience. Seán MacDermott’s last letter to his siblings was characteristically insouciant (‘just a wee note’) but ended: ‘I feel a happiness the like of which I never experienced in my life before, and a feeling that I could not describe. Surely when you know my state of mind none of you will worry or lament my fate . . . I die that the Irish nation may live.’52

These testaments reflect a genuine state of exaltation, but were also part of the revolutionary strategy, and would prove infinitely more potent weapons in the cause of separatist nationalism than Howth Mausers or Larkfield billy-can bombs. They tapped into the long tradition of speeches from the dock enshrining national martyrology, endorsed by Catholic traditions of holy dying and sacrificial blood. James Connolly received Communion before his death and enjoined his wife to adopt Catholicism. Roger Casement similarly converted, as did Constance Markievicz. The socialist activist Michael Mallin, in a passionate and harrowing last letter, asked his wife not to remarry and called for his children to become priests and nuns. Very rapidly, the language of mystical Catholicism fused with national purism in a new – or ancient – revolutionary rhetoric. The Catholic Bulletin quickly adopted the rebel cause, collecting evidence of such miraculous interventions as Cathal Brugha curing his gunshot wounds by the application of holy water from Lourdes. As early as 17 May, at a memorial Mass in San Francisco, the Reverend F. A. Barrett specifically identified Pearse, Clarke and the rest with the ‘saints and martyrs’ of the Catholic Church; in a ‘brilliant triumph’ they had redeemed Ireland from the stain of those ‘thousands of Anglicized degenerates [who] have died for the heretical power that slew their fathers and persecuted their Faith; at the magic words “Faith and Fatherland” the chivalrous sword of truth leapt from her scabbard . . . The insurrection has safeguarded our Faith. Before the war we were daily approximating to England, our Catholic ideals were disappearing, the process of Anglicization went forward apace. That fatal process is arrested.’53

The implications for a Home Rule policy, now irredeemably associated with British imperialism, were all too clear. Though Redmond and his colleagues launched a desperate last effort to get Home Rule implemented, Partition was now an inevitable part of the deal. In any case, the revolutionary leaders’ entry into Valhalla meant that negotiation – or ‘give and take’ – no longer stood much of a chance, as Yeats declared in one of the troubled poems inspired by the Rising, and released slowly to the public over the next months.

You say that we should still the land

Till Germany’s overcome;

But who is there to argue that

Now Pearse is deaf and dumb?

And is their logic to outweigh

MacDonagh’s bony thumb?

How could you dream they’d listen

That have an ear alone

For those new comrades they have found,

Lord Edward and Wolfe Tone,

Or meddle with our give and take

That converse bone to bone?

Home Rule, and an unpartitioned Ireland, were not the only futures now receding from the realms of possibility. As with the patriarchal attitudes demonstrated within the GPO and elsewhere, the promulgation of traditionalist attitudes to faith and fatherland shifted the emphasis from the broader forms of liberation variously hoped for by people such as the Sheehy-Skeffingtons, the MacDonaghs, Bulmer Hobson, Patrick McCartan, Kathleen Lynn, Louie Bennett, the Gifford sisters, P. S. O’Hegarty, Rosamond Jacob, Mabel FitzGerald, Kevin O’Shiel, Cesca and Margot Trench. Feminism, socialism, secularism and various forms of pluralism were now discounted.

Cesca Trench, so ecstatic at the time of the Howth gun-running, and given to much self-congratulatory Anglophobic ranting, found herself appalled at the carnage of the Rising. Just before the end of hostilities she wrote:

This mad affair has done irreparable damage to the cause of Irish freedom which it is meant to serve, as it can only succeed by a miracle which isn’t likely to occur. God help us, I think it will break all our hearts . . . It was done against the leaders of the Irish Volunteers & all the sensible men among them, but there are many who will suffer innocently. Séumas [James] Connolly is a man whose chief merit is his desire to see his country free, but he has no other qualifications for an affair of this kind. Most of the others are high-minded but utterly lacking in judgement, poets, or they wouldn’t have run us into such idiocy.54

In this she may have been influenced by her fiancé, Diarmuid Coffey, who had maintained his scathing analysis of the revolutionary element among the Volunteers and the threat they represented to Home Rule. But the executions swayed Cesca’s opinions in favour of the rebels, and in this she reflected a much wider mood.

Another nationalist from a Protestant background, Rosamond Jacob, found herself deeply affected by the eerie atmosphere after the dust had settled. The news had filtered through to Waterford the day after the rebellion began, and as usual she found herself arguing with her friends, particularly Ben Farrington, who, though a Sinn Féin supporter, was ‘just as I expected – what good would this do, and the country didn’t sympathize with it etc., etc.’ Jacob herself felt deeply disturbed and excited, and her sense of living on the margins was unbearably accentuated. She spent much time with her nationalist friends the Powers at the Metropole Hotel in the town, where many of the revolutionary leaders (including Pearse) had stayed in the past. The news of the executions struck a knell; Kitty Power said that she ‘never would have thought she could hate England more than before’. They consoled each other by reading Pearse’s writings in back numbers of Irish Freedom and the Irish Review. Jacob, who had met Pearse in the past and been disappointed by his unattractively plump appearance and flabby handshake, now revised her opinion drastically; as soon as she could get to Dublin she made a pilgrimage to St Enda’s, tried to buy copies of Pearse’s last pamphlets, and eventually managed to pay her respects to his mother and sister, sitting reverently in their drawing-room and looking at relics of the dead brothers. Above all, she was ‘all the time suffering from envy & jealous of the people I met who had been out in the Rising; it seems as if I was destined to be an outsider & a looker-on all my life; never to be in it.’55

Everywhere there were changes. Jacob visited the smoking ruins of the GPO, and learnt that her friend Madeleine ffrench-Mullen and her brother Douglas were in gaol, having served respectively in the College of Surgeons garrison, and with Ceannt in the South Dublin Union. Another radical friend, Elizabeth Somers, had been arrested and interned, while her mother and brother had lost their jobs. Jacob’s friend Hanna Sheehy-Skeffington, steely despite her traumatic widowhood, was refusing to see her brother, who was in the British Army, and at daggers drawn with her father-in-law, who wanted to take his grandson Owen from her. (Nonetheless Jacob rather censoriously judged that ‘she seems to see Owen somewhat as a burden – only for him she could easily have got herself killed at Easter, and she’d rather he was a girl anyway.’) Hanna was in the process of becoming a powerful and influential voice for Irish republican claims and a witness to the horrors of British military rule; she would make a successful tour of America in 1917, to the irritation of conservative Irish-Americans, one of whom damningly described her as ‘a suffragist, pacifist, vegetarian, prohibitionist, anti-tobaccoist and professional writer, and looks all these things’.56

Jacob found her liberal Quaker relations in Rathgar, the Webbs, surprisingly sympathetic towards the rebels, while regarding the enterprise as mad (‘not knowing anything about their expectation of German help, or MacNeill’s goings on’).57 She heard accounts of other survivors whom she had met in pre-revolutionary days, such as the Gifford sisters, Muriel MacDonagh and Grace Plunkett, both now the unhappy widows of two signatories. Muriel would drown while swimming the next year, while Grace had retreated to the Larkfield commune, where, as we have seen, she suffered the miscarriage or abortion allegedly witnessed by her new sister-in-law Geraldine. She subsequently spent much time trying to extract money from the unsympathetic Plunkett parents, and producing her trademark caustic cartoons for the republican cause.

For the Ryan sisters and their friends, who had been at the storm-centre, life after the Rising was also dramatically turned upside down. The eldest sister, Nell, who had been at home in Wexford throughout, was interned ‘on the ground that she is of hostile associations and is reasonably suspected of having favoured, promoted or assisted an armed insurrection against His Majesty’.58 Mary Kate was also arrested, probably because of the suspicious company she kept (the regular attendants at her Ranelagh Road flat, O’Kelly, MacDermott, Liam Ó Briain and Seán Forde had all taken a prominent part in the Rising). She was soon released but Nell was passed through several gaols – Kilmainham, Mountjoy, Lewes, and finally Aylesbury, along with Helena Molony, Marie Perolz and Constance Markievicz. She remained in exile until October, studying Russian and Persian in prison and receiving gifts from admiring local suffragettes, as well as eggs, butter, onions and honey from the bounty of Tomcoole.59

Min and Phyllis, though they had played an active part in the GPO and as couriers, were not arrested, but their brother James was imprisoned in Stafford, and later in the celebrated internment camp at Frongoch, where so many revolutionaries ended up. The comradely atmosphere there made it a memorable experience, and he later wrote to his imprisoned sister Nell, only half in jest: ‘I always keep telling people that you don’t mind in the least being away, and I know from experience that it is quite true. You would hardly believe how sorry I feel sometimes that the whole thing is over. Indeed if it were not for the pleasure it seems to give others I don’t see any advantage at all in being out.’60

James returned, along with many others, in the summer of 1916, finding Dublin changed and lonely, with the searing loss of old friends. ‘But new ones are ready to take their places, that’s as far as opinions etc. go . . . The people are regenerated right enough, so there it ends.’61 Richard Mulcahy, another friend (and future husband of Min Ryan), was imprisoned in Knutsford and Frongoch, retaining vivid memories of the initial privations of solitary confinement and constant hunger. However, thanks in part to pressure brought by Redmond and his colleagues in official quarters, the Irish prisoners were subsequently put under conditions of internment instead, an open-door policy which allowed them ‘the run of the place and complete association with one another’.

. . . our minds were quite relaxed and unconcerned and waiting with a cheerful outlook for changes in the situation. There was nothing we could do about anything. We were all quite satisfied that something important had happened. We were all satisfied that there was a sufficient number of us in the position of prisoners to have a strength that could afford to feel quite peaceful, and there was a tremendous development of a feeling of satisfactory comradeship.62

Seán T. O’Kelly, faithful follower of the Ryan sisters, remained in prison (Wandsworth, Woking, Frongoch and Reading) until December. The following year he would be transferred under internment conditions to Oxford and Gloucestershire. Throughout, he kept in touch with the girls as they accustomed themselves to an altered world. Min was haunted by her last visit to MacDermott (who had become her ‘matrimonial aspirant’ by the end of 191563), a poignant event she remembered vividly for the rest of her life.

It was ridiculous in a way because there was no sign of mourning. We [her sister Phyllis and herself] had to hold up, of course, when he held up, and so we showed no sign of sorrow while we discussed things . . . He had five good cigarettes and a few ‘Wild Woodbines’ that the soldiers had given him, and he was arranging to smoke them so that they would last him almost up to the end. When we left him at 3 o’clock he had two cigarettes still to smoke, and he was to be shot at a quarter to four. He spoke with much affection of several young men and women he used to meet with us, and the most pathetic scene was where he tried to produce keepsakes for different girlfriends of his we mentioned. He sat down at the table and tried to scratch his name and the date on the few coins he had left and on the buttons which he cut from his clothes with the penknife somewhat reluctantly provided by the young officer who stood by . . . When the priest appeared at three o’clock . . . we stood up promptly and felt a great jerk, I’m sure all three of us, to say good-bye. I was the last to say good-bye to him and he said, just said: ‘We never thought that it would end like this, that this would be the end.’ Yes, that’s all he said, although he knew himself, long before that, what the end would be for him.64

After her brief imprisonment Mary Kate continued with her UCD duties, enduring accusations from the President, Dr Coffey, that she preached subversive politics to her students.65 The whole family frequently returned to the farmhouse at Tomcoole, and their letters to the imprisoned members of the family describe the routines of the farming year, the dairy, the turkeys and hens, the horses, the sale of stock, the flower-garden by the house coming into its own in the early summer, the state of the grass in the meadow, the saving of the hay. But they also measure the unmistakable shifting of attitudes, the increasing sympathy of neighbours towards a known republican family, the decline of the old Home Rule order in its heartland of Wexford town. In June a local priest had written to Mary Kate, still in Mountjoy Gaol, of the change of spirit in the county. ‘Even facial expressions have changed for the better. Remorse has set in. And many are struggling to swallow their words and whitewash their works. But lime cannot be had for the asking nowadays.’66

That August saw a double wedding at Taghmon Church, of Chris Ryan to Michael O’Malley and Agnes to Denis McCullough, released from Frongoch only just in time. A large and reverent crowd assembled; the wedding car was driven by an ex-employee of White’s Hotel, Wexford, of whom the Ryans approved because he had been dismissed for republican activities. With Nell in prison and so many friends recently dead, it was a subdued affair; several guests wore sombre clothes and as a mark of respect there was no dancing. The brides wore Irish poplin, and the service was in Irish.67 O’Kelly wrote disconsolately to Mary Kate from prison of his wish to be there: ‘I am drawing mental pictures of all garbed in fine new finery . . . You will I hope permit me to think of myself as being somewhere near you on that day in particular whispering a word or two in your ear as occasion offers and being treated now and then to a smile in return.’