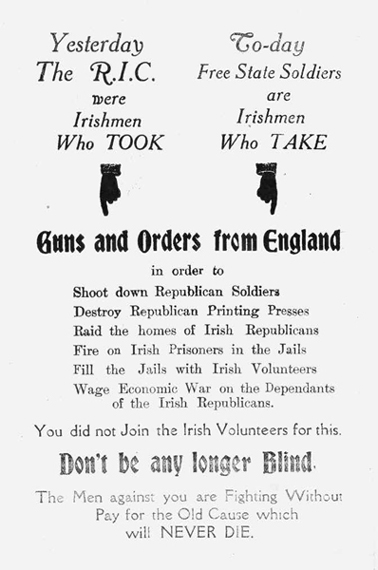

A republican poster makes the case that the Free State represents a restoration of the ancien régime.

The hide was being flayed off the still living body of the Revolution so that a new age could slip into it; as for the red, bloody meat, the steaming innards – they were being thrown on to the scrapheap. The new age needed only the hide of the revolution – and this was being flayed off people who were still alive. Those who then slipped into it spoke the language of the Revolution and mimicked its gestures, but their brains, lungs, livers and eyes were utterly different.

– Vasily Grossman, Life and Fate (2006)1

I

Between the Easter Rising and the end of the world war, the face of Irish politics had changed, and the surviving revolutionaries had taken charge; but they did not present a united front. Nor was the future fixed. In the aftermath of the Rising, Seán T. O’Kelly was outraged at the efforts made by the Plunketts to emerge as a kind of First Family of republican politics, with the elderly Count pushed hard as a leader of a ‘Liberty League’ intended to take over the reconstructed Sinn Féin movement. O’Kelly believed that he was being manipulated by the influential Sinn Féin cleric Father Michael O’Flanagan, who wanted to become ‘boss and political dictator’ of Ireland, using Plunkett as his instrument and exploiting the martyred Joseph Plunkett’s reputation. Though O’Flanagan was reconstructing himself as quickly as anybody else in these bewildering times, his unsupportive attitude in 1916 was held against him (he had allegedly referred to the GPO garrison as ‘murderers’ who should be allowed to burn to death). ‘And whoever heard tell of Countess Plunkett as a political leader?’2 The one thing that united the revolutionaries was the need, as O’Kelly put it, to ‘rid the country of the Party incubus’. Mary MacSwiney similarly feared the revival of a Home Rule agenda, on the basis of agreeing to Partition, and dreaded the thought of Redmond emerging at a post-war peace conference as Prime Minister of Ireland. ‘Better martial law and General Maxwell.’3 As ever, the one thing that the comrades could agree upon was that the real enemy was the Irish Parliamentary Party.

To their relief the Redmondites’ fate was sealed by the failure of the British government (now headed by Lloyd George) to impose a form of Home Rule after the Rising. This abortive effort was compounded by the looming prospect of introducing conscription for Ireland, and the inept coercion measures introduced from Dublin Castle at the behest of the bone-headed military commander, Field Marshal Lord French (who would be appointed Lord Lieutenant in May 1918), enthusiastically rounding up respectable supporters of the Irish Parliamentary Party along with supposed radicals. As early as June 1916, the change in the public mood was noted by no less an authority than General Maxwell himself:

There is a growing feeling that out of rebellion more has been got than by constitutional methods, hence Mr Redmond’s power is on the wane, therefore this desire to curry favour with the people on the part of M.P.s by agitating for the release of Sinn Féiners.

It is becoming increasingly difficult to differentiate between a Nationalist and a Sinn Féiner.

Mourning badges, Sinn Féin flags, demonstrations at requiem masses, the resolutions of public bodies are all signs of the growth of Sinn Féin.

Recruiting in Ireland has practically ceased . . .

If there was a General election very few, if any, of existing nationalist M.P.s would be re-elected so there is a danger that Mr Redmond’s party would be replaced by others perhaps less amenable to reason.4

From a different perspective, others also sensed that the wind was changing. Down in Cork, Liam de Róiste, attuned as ever to the zeitgeist, noted excitedly: ‘We live in a new era.’5

For the revolutionaries, the post-Rising fallout, and the large-scale imprisonment and deportation of leaders, initially led to a certain vacuum of power, with efforts made to fill the gap by short-lived organizations such as Kevin O’Shiel’s Irish Nation League. Nationalist journalism, despite censorship restrictions, was as effective as ever; even in internment and gaol, the revolutionaries kept their hands in by publishing free-sheet periodicals with titles like Barbed Wire, unhampered by the prison authorities. Outside prison walls, the Catholic Bulletin, edited by J. J. O’Kelly, continued to be the repository for the celebration of the cult of nationalist martyrs. Significantly two newspapers supporting the doomed Irish Parliamentary Party, the Evening Telegraph and the Freeman’s Journal, went into liquidation in September 1919, and when the Freeman revived under a new owner it took a line far more tolerant of Sinn Féin. This was yet another sign that the party, now reconstructed as a republican movement, was claiming the future.

Backed by the groundswell of prisoners’ aid societies, dispersing lavish funds raised from Irish communities worldwide, organized by local clubs, adhering to a new ideology and energized by the revolutionary indoctrination and esprit de corps infused through prison and internment experiences, the revolutionaries took over Sinn Féin and swept the country. One surprising result was the re-emergence of Arthur Griffith as a key player, rehabilitated by imprisonment, and benefiting from the fact that what was essentially a new organization still retained the old name of Sinn Féin. From gaol he had issued influential memoranda, blueprints for action and manifestoes to the faithful.6 Released, he revived his influential paper Nationality, preaching the need to ‘scotch the old snake’ of the Irish Parliamentary Party and to make Ireland’s claims felt at the Versailles Peace Conference. As with Father O’Flanagan, some did not forget his chequered past history; Michael Collins privately referred to him as ‘pretty rotten’ on the separatist issue, and reassured Thomas Ashe (in Lewes Gaol) that ‘Master A. G. is not going to turn us all into eighty-two-ites.’7 In other words, any arrangement under the British crown resembling Grattan’s Parliament of 1782 was out of the question. Griffith accordingly had the political nous to concede the presidency of Sinn Féin to a new-minted hero of the Rising, Éamon de Valera.

Though he rapidly became the acknowledged leader of the revolutionary movement and would dominate Irish political life for much of the century, de Valera had come to prominence suddenly, and from a position of some obscurity. Thirty-three years old at the time of the Rising, to observers like Rosamond Jacob he was an unknown quantity: the subject of rumour and speculation, and sometimes described as a mysterious ‘Spaniard’. In fact, though born in America to an Irish immigrant mother and her short-lived Basque husband, he had grown up in rural County Limerick among his mother’s family. His career as a teacher had not brought him into the circles of Mary Kate Ryan’s Ranelagh salon, or Griffith’s watering-holes, or the newspaper offices of the radical press. He himself was conscious that he was at an angle to this universe, remarking to Mary MacSwiney in 1922, ‘every instinct of mine would indicate that I was meant to be a dyed-in-the-wool Tory, or even a bishop, rather than the leader of a revolution.’8 It is significant that he saw his destiny as bishop rather than simply priest. He had elevated himself from an impoverished background through brains and hard work, attending one elite boarding-school and teaching mathematics and physics at another. Radicalism had played little part in his life until he took up the Irish language around 1908, and his politics seem to have been Home Ruler rather than republican until he joined the Volunteers in 1913. Even then, though he went with the dissidents in 1914, he was not in the inner circles of the IRB, and left the movement after 1916. But through membership of the 3rd Battalion of the Irish Volunteers he had become closely associated with the charismatic Thomas MacDonagh, and this was the first step on the road to his command at Boland’s Mill.

De Valera was narrowly spared execution, not so much because of his American birth as because Maxwell was assured that he was an unimportant figure. His rapid prominence owed much to his status as a surviving commander of a 1916 garrison, as well as his age, his imposing presence (he was extremely tall), his schoolmasterly authority and his self-belief; he also had a gift for inspiring admiration and affection in many of his comrades, though this was a far from universal reaction. His taste for power was helped by his ability to project a kind of aloof charisma, though, on a 1919 fundraising tour in America, Patrick McCartan also noted his colleague’s growing distaste for contradiction and even discussion. These tendencies were accentuated by his long experiences of religious institutions; he told his election supporters in 1917 that he had been associated with priests all his life, ‘and the priests know me and are behind me.’ In October 1917 he became President both of Sinn Féin and of the Irish Volunteers. But to many of the people who had been immersed in revolutionary organizations before the insurrection, he was a new and slightly surprising figure, whose unexpected dominance was not entirely welcome.

From 1917, especially after the serendipitously timed release of the prisoners, the movement entrenched itself in Irish political life. The process was accompanied by a flow of post-Rising propaganda which, though crisply described as ‘bilious, turgid and maudlin’ by a later historian of the organization, caught the mood.9 Less pietistically, local elements began to make threatening moves towards an aggressive land agitation policy. ‘Cattle drives’ carried out by landless men against the bitterly resented grazier farmers in the West had already flared up in 1907–8, and were revived in the winter of 1917/18, encouraged by elements of Sinn Féin. Even de Valera briefly lent his support to the vague concept of ‘even land division’, and fields were occupied ‘in the name of the Irish Republic’, to the alarm of more conservative leaders. Acute social conflict was only narrowly averted in some instances.10 The remnants of the Citizen Army, as well as representatives of the trade unions movement, were also swept up into Sinn Féin. Their belief that a new Ireland could be socialist as well as republican was uncomfortably received by their more cautious colleagues, though for the moment the cause of Sinn Féin and freedom from British rule could be invoked as a unifying mantra. Griffithites, nonetheless, stressed more easily negotiable themes such as over-taxation, and the need for representation in settlement negotiations after the world war ended. More military-minded radicals (including, rather ambivalently, de Valera) talked of guns, drilling, reviving the spirit of Volunteering and fighting for the republic. ‘Soldiers’ and ‘politicians’ were already regarding each other suspiciously, and the implicit tension between moderate and extremist elements stretched to other issues besides that of separation from British rule. Radicals like Máire Comerford would later come to see the division as prophetic.

But, as 1918 dawned, the British government yet again offered unintended succour to the revolutionaries, by moving towards compulsory conscription of Irishmen into the British Army. Even before Irish opinion had turned conclusively against the war effort, compulsory drafting of Irish civilians had been deemed unacceptable; to introduce the idea at this stage was incomprehensibly obtuse. A general sense of outrage enabled a powerful opposing coalition across Irish life, allowing senior clerics to appear on platforms with Sinn Féin ex-prisoners, while British policies of ineffective coercion and random internment on trumped-up charges (notably an outlandishly conceived ‘German Plot’ in May 1918) played even more generously into the nationalists’ hands. W. B. Yeats, observing Irish politics as closely as ever, wrote imploringly to the Liberal politician Lord Haldane after a visit to Dublin:

I have met nobody in close contact with the people who believes that conscription can be imposed without the killing of men, and perhaps of women . . . there is in this country an extravagance of emotion which few Englishmen, accustomed to more objective habits of thought, can understand. There is something oriental in the people, and it is impossible to say how great a tragedy may lie before us. The British Government, it seems to me, is rushing into this business in a strangely trivial frame of mind. I hear of all manner of opinions being taken except the opinion of those who have some knowledge of the popular psychology . . . it seems to me a strangely wanton thing that England, for the sake of fifty thousand Irish soldiers, is prepared to hollow another trench between the countries and fill it with blood. If that is done England will only suffer in reputation, but Ireland will suffer in her character, and all the work of my life-time and that of my fellow-workers, all our effort to clarify and sweeten the popular mind, will be destroyed and Ireland, for another hundred years, will live in the sterility of her bitterness.11

But his words fell on deaf ears; and Yeats’s own opinions were, by now, moving towards support of the Sinn Féin programme, precipitated by despair at the destructiveness of British policy.

This process was facilitated, for him and for others, by the fact that Sinn Féin remained an apparently broad church. To the fury of many members, even Eoin MacNeill – of all people – now reappeared as a prominent figure, astutely defended by de Valera and others. Those ‘out’ in 1916, even if not very notable as combatants, were nonetheless in the ascendant. Seán T. O’Kelly, returned from his comfortable internment, emerged as Sinn Féin’s Director of Organization. But the reins of power increasingly were assumed by new people, notably Michael Collins and his dashing friend Harry Boland, who exerted a decisive influence in nominating Sinn Féin candidates at elections (only three candidates at the post-war general election had not been gaoled or interned). Their efforts culminated in a dramatic landslide success at the polls in December 1918, effectively eradicating the Irish Parliamentary Party. The 69 Sinn Féin victors, representing 73 seats (since some were elected twice over), included Liam de Róiste, James Ryan, Desmond FitzGerald, Robert Barton, Richard Mulcahy, Terence MacSwiney, Piaras Béaslaí, Patrick McCartan, Seán Etchingham and several other familiar names from the pre-revolutionary era. Constance Markievicz was also returned: one of only two women candidates, despite the new franchise, and the prominence of women in the revolutionary movement before 1916. The anomaly was angrily noted by Rosamond Jacob and other activists, who despaired of making headway against entrenched male attitudes ‘outside Dublin’.12

II

The elected members constituted a legislative assembly which, following the original Griffithite line, boycotted Westminster and withdrew to Dublin to set up their own parliament, Dáil Éireann (‘Assembly of Ireland’). Twenty-eight Sinn Féin deputies assembled in Dublin’s Mansion House on 21 January 1919 (the remainder being in gaol or otherwise engaged), accompanied by enthusiastic supporters, and found themselves almost incredulously faced with the opportunity to make their dreams and theories come true. Máire Comerford remembered it long afterwards:

No day that ever dawned in Ireland had been waited for, worked for, suffered for like that January Tuesday.

People waiting asked one another, ‘Did you ever think you and I would live to see this day?’

I was with a Wexford contingent.

Never was the past so near, or the present so brave, or the future so full of hope.

We filed into the Round Room and pressed round till every inch of standing room was full.

I don’t believe I even saw the seating arrangements that first day, the crowd was so great.

We did see Cathal Brugha presiding and we repeated the words of the Declaration after him, and felt we had burnt our boats now. There was no going back.13

Comerford was there as a Sinn Féin member, not as an elected representative (Teachta Dála, or ‘TD’, meaning member of the assembly). However, women were more prominent in the national organization of Sinn Féin, where Kathleen Lynn was Vice-President, Hanna Sheehy-Skeffington Director of Organization and Áine Ceannt (widow of the 1916 signatory Éamonn) Director of Communications. After the election, the party had been defined as ‘a large legislative assembly, a small executive and an intermediary body which helped bridge the gap between them . . . democratic almost to excess’; the mass membership may have reached about 130,000.14 A complex party structure was created, from local clubs up to the ard-comhairle (governing body). It boasted an ambitious agenda, which included not only alternative governmental institutions at home but the development of consular representation abroad. (This created social opportunities much relished by upwardly mobile sophisticates such as Art Ó Briain and the O’Kellys.) The Dáil’s publicity department under Robert Brennan produced an efficient and influential news-sheet, the Irish Bulletin, edited by Desmond FitzGerald and contributed to by Erskine Childers and Frank Gallagher; the staff moved its production process around various safe locations, including the Irish Farm and Produce shop in Baggot Street (where it had moved when its Henry Street premises were destroyed in 1916), Robert Brennan’s basement in Belgrave Square and Diarmuid Coffey’s mother’s drawing-room. Much power was vested in the Dáil’s Standing Committee, and in its President, de Valera. The Dáil laid down the blueprint for a shadowy secessionist government, republican in form. Its relationship to, and authority over, the remnants of the paramilitary Volunteers was declared, but remained questionable. Nonetheless the revived Volunteering movement, now openly organized by the IRB, was increasingly called the Army of the Irish Republic, or the IRA.

In early 1919, the drift to guerrilla war against government authorities was not yet inevitable. Many Sinn Féiners saw their new-found position as public representatives primarily as enabling them to present their case at the Versailles Peace Conference, where Seán T. O’Kelly and Mary Kate found themselves in February. They settled into the Grand Hotel, headquarters of the Sinn Féin delegation; letters to the other Ryan sisters were grandly headed ‘Gouvernement provisoire de la République irlandaise’.15 Seán would remain in Paris and later Rome for much of the next two violent years – a fortunate circumstance for himself, later bitterly noted by his enemies. Ill for some weeks, he was nursed in the Irish College at Rome, and cemented an important relationship with several influential Vatican figures. The experience reinforced his already devout Catholicism, which would characterize his later political career. Through the efforts of envoys like O’Kelly, a large amount of the money raised by the Dáil was earmarked for the purpose of pressing the Sinn Féin case on generally uninterested foreign representatives.16

Hopes of official American support for the Dáil’s initiative remained high, but were unfulfilled. Trying another tack, Patrick McCartan made enterprising overtures to the new Russian government. Early contact had been established with Bolshevik envoys in New York, sending imaginative blandishments (‘the Republic of Ireland is, as you know, working directly and consciously towards an economic basis of government: that is, towards an application of the Soviet principle’).17 The irrepressible McCartan travelled to Russia in early 1921, confident that he could persuade Foreign Minister Litvinov to recognize the nascent Republic of Ireland. Unfortunately the diplomatic weather had turned, and the Russians were now hoping for an agreement affording formal recognition from Britain (which would indeed be signed, ironically, the following St Patrick’s Day). McCartan’s carefully constructed arguments that perfidious Albion was an implacable enemy both to the Russian and to the Irish revolutionary regimes fell on barren ground. He tried to persuade his sceptical Bolshevik acquaintances that the Irish were essentially pro-communist, while also suggesting under the heads of a draft Irish–Soviet Treaty that the Republic of Ireland would protect the interests of the Catholic Church in Russia.18 But his hopes were finally dashed when his chief contact was suddenly spirited away to a ‘sanatorium’ for a ‘rest’; unsurprisingly, McCartan never heard from him again. All that was left for him was to compile a long and perceptive report on conditions in Russia, and to make his difficult way home. He had discovered, as Casement had in Washington and Berlin and O’Kelly at Versailles, that the international diplomatic influence wielded by Irish revolutionaries was necessarily limited.19

Simultaneously, and more to the point, raids were beginning to be carried out on police barracks in rural Ireland by the IRA, and the Anglo-Irish War was sputtering into life. Assassinations of policemen, though denounced by several influential clerics, were becoming the real currency of revolt. This escalation of violence had much more to do with local initiatives than Dáil policies; the soldier–civilian divide was now openly evident.20 The reconstituted Volunteer newspaper An tÓglách, now edited by Piaras Béaslaí, printed injunctions to revolutionary violence which echoed the language of paramilitarism elsewhere in Europe. An article called ‘Ruthless Warfare’, anonymously contributed by Ernest Blythe, declared that anyone supporting conscription ‘merits no more consideration than a wild beast and should be killed without mercy or hesitation as opportunity affords’.21

The ‘glory days’ of democratic Sinn Féin were over, and the locus of decision-making was shifting elsewhere. Irish ‘experts’ in London, such as the acute British civil servant Lionel Curtis, judged that at this point control passed ‘from the intellectuals to leaders of a different type’:

With such forces at their disposal, the leaders would probably have ventured on open rebellion if matters had come to an issue before the war. But in 1919, realizing the terrific power of modern artillery against troops in the open field, they resorted to the weapons with which centuries of agrarian oppression had familiarized Ireland. As formerly the landlords and their agents, so now officers of Government became marks for the bullets of assassins.22

The Dáil continued to sit secretly, and to represent a cross-section of the revolutionary movement. Early on, a ‘Democratic Programme’ had been articulated, drawn up largely by the labour leader Tom Johnston, aided by the ubiquitous O’Kelly and Mary Kate, and read aloud to the assembly by their friend and brother-in-law Richard Mulcahy.23 In a formulation lifted bodily from Pearse’s pamphlet The Sovereign People, the ‘Democratic Programme’ vested national sovereignty in the whole nation, along with ‘the soil and its resources and all the wealth producing processes’; private property rights were to be subordinate to ‘the public welfare’ and guarantees of comfortable subsistence and free education issued to all the nation’s children. Radicals like Máire Comerford would remember its promises sadly in the distant future.24

The ‘Democratic Programme’ may have been drawn up with an eye to the contemporaneous International Socialist Congress in Switzerland, where Irish labour was claiming the right of representation. This was yet another initiative of Griffith’s, his belief in the value of international publicity outweighing his dislike of socialism. The language of social – even socialist – egalitarianism continued to be yoked to that of nationalist struggle, notably in a speech of de Róiste’s at the 1920 Trade Union Congress in Cork.

The workingmen of Ireland during the past five or six years had shown that they were the only democracy in Europe that understood thoroughly what democracy was . . . They were animated by the three greatest forces on earth – the spirit of democracy, the spirit of nationality, and the spirit of true religion . . . these three forces were combined in Ireland, and they were invincible and unconquerable . . . If democratic forces did not win the alternative was the old system of militarism and capitalism, crushing the workers in all countries.25

But the language of workers’ democracy faded fast, while the third element of de Róiste’s triumvirate came into stronger and stronger relief; observers were already noting the ‘sombre bodyguard of priests’ surrounding de Valera as he ascended political platforms, and Rosamond Jacob was characteristically alert to the growing identification of Catholicism with nationalist identity. The transformation of the Anglo-Irish Tory grandee Lord Midleton’s sister, the Hon. Albinia Brodrick, who rechristened herself Gobnait ní Bruadair and became a dedicated Sinn Féiner, should have pleased Jacob. But ní Bruadair’s declaration of love for ‘her beloved people and their religion’ was a step too far. ‘I’m in a fright now for fear she may turn Catholic herself, like Casement and Madame de Markievicz. I do dislike to have things look as if no one could be a Sinn Féiner without being a Catholic.’26

III

With the failure of the Versailles initiative, the Irish revolution continued to lurch into a more militaristic mode. The IRA was organized into an elaborate structure of brigades, battalions and commands, though it proceeded ‘by instinct rather than theory’; pre-war training and drilling in the Volunteers could only count for so much.27 As Chief-of-Staff, Richard Mulcahy threw himself into its organization, maintaining a huge correspondence with comrades in the provinces and responding to an enormous variety of inquiries, preserved meticulously in carbon copy. Despite his military success in 1916, he would henceforth fight his battles from behind an administrative desk, which may have better suited his austere and shy character. The threat of anarchy loomed in certain parts of the country where the police authority was compromised or routed by the increasingly daring and effective ventures of IRA flying columns. The Royal Irish Constabulary’s pleas to be released from its paramilitary role fell on deaf official ears. Its possession of weapons attracted more and more expropriatory raids from the IRA, and its relationship to local communities, always equivocal, became impossible to sustain. In the year from January 1920 to January 1921, the number of police stations in County Mayo was exactly halved – a pattern repeated in other areas where guerrilla activity was rife.

Simultaneously the ‘virtual’ government of the Dáil asserted its own authority over aspects of local government, police and litigation – scoring a considerable propaganda victory with the last, since the Sinn Féin courts actually worked effectively and were sometimes patronized by the most unlikely clients. This success owed much to the conservative nature of many of the judgments passed down, and to the involvement of priests; Sinn Féin ideologues such as Darrell Figgis argued strongly against the nascent revolution falling into ‘the snare of class war’. The much mythologized ‘Limerick Soviet’, which ran the city for twelve days in April 1919, in defiance of crown authorities, did not contradict this. (Far from a Soviet-style takeover, it was a general strike against the government’s security policy; though thirteen creameries were also claimed to be under workers’ control, this was a rhetorical rather than an ideological gesture.) Other arms of the state, such as the Post Office, were exploited as networks of communication, heavily infiltrated by republican sympathizers. As with the rebel occupation of Dublin in 1916, the longer Sinn Féin’s rudimentary alternative state lasted, the more credibility it accrued.

But the survival of this ostensibly pacific strategy, as with the Land War boycott forty years before, depended upon the sanction of violence as well as on the support of the community; the scorched ruins of country barracks stood behind the decorously convened Sinn Féin courts. So did the money raised by local levies, and the enterprising loan schemes pioneered and administered by Michael Collins. Above all, terror and counter-terror marked the course of events in certain areas of the country where support for the IRA was shored up by its growing powers of intimidation.28 With the opening of the bloody year of 1920, as authority leached away from the forces of the crown, Lloyd George’s coalition government embarked on the draconian and disastrous policy of drafting in hastily recruited military police, soon to be dubbed ‘the Black and Tans’. Their record of undisciplined operations against the civilian population, and their random ‘reprisals’, gave the revolutionaries both an identifiable enemy in the classic mould of the vicious oppressor and another invaluable propaganda victory.

By May 1920 a government report written by Warren Fisher provided a devastating picture of British rule in Ireland: ‘woodenly stupid’, completely out of touch with any opinion outside Ascendancy circles, and incapable of realizing that ‘two-thirds of the Irish people and over 70 of their MPs are Sinn Féin and that the murder etc. gang are a few hundreds’. This exasperation was echoed in a significant Cabinet report a couple of months later, recognizing that the majority of the Irish population outside Ulster, including unionists, ‘were embracing, however reluctantly, the new ideas, and were not unwilling to make use of the Sinn Féin courts; in the circumstances, it was necessary that the Government should review its policy, and the length it could go to in offering concessions.’29

The same Cabinet minute recognized that, with the passing of the Government of Ireland Act earlier that year, ‘Ireland’ as traditionally conceived was no more. The island was now formally partitioned. The separation of the north-east had long been inevitable – a policy floated behind the scenes in government circles since the stand-off of 1911–12, and implicitly but silently acquiesced in by more nationalists than liked to admit it. Southern unionists had long forecast their eventual abandonment (as they saw it) with considerable foreboding. The unionist lawyer James Campbell had presciently told the government in May 1916 that partitioning Ireland would be ‘a desperate and dangerous gamble’, which, even if successful, would ‘permanently divide the Irish nation into two hostile sections, each bearing the statutory brand of a distinctive religious sentiment’. As to the promises made to nationalists and unionists alike by British politicians, ‘one side or the other is going to be deceived in this matter with the inevitable consequences of bitter recrimination and renewed agitation.’30

Sinn Féin revolutionaries felt no differently, but since the facing down of the government by the UVF in 1912, Partition was always on the cards. Friends of Ulster unionism, entrenched at the centre of Lloyd George’s government, saw to it that the revived Home Rule Bill – which came into being as the Government of Ireland Act (1920) – would underwrite the new six-county statelet in the North, whereas the Act’s stipulations for the remaining twenty-six counties were a dead letter from the start. The all-Ireland dreams, fantasies and wishful thinking of Ulster nationalists such as Bulmer Hobson, Alice Milligan, Patrick McCartan, Denis McCullough, Roger Casement and F. J. Bigger were equally moribund. Bigger would retreat into regretful antiquarian seclusion at Ardrigh, removing himself from the vanguard of cultural nationalism, while Hobson, McCartan and McCullough made their lives in Dublin. Alice Milligan would eventually and unhappily return to the North, and a very different world from the revived Gaelicist order which she had so enthusiastically evangelized before the revolution.

The creation and maintenance of Northern Ireland, however, claimed little of the revolutionaries’ attention, as the war prosecuted by the IRA in the rest of the island proceeded to escalate. The derring-do and bravado of IRA flying-column actions in the mountains of the south-west was counterpointed with gangland-style assassinations by Parabellum automatic pistols. The bloody month of November 1920 saw an ambush at Ballinalee, County Longford, led by the legendary IRA leader Seán MacEoin, in which as many as twenty crown forces died; the killing of fourteen British officers in their Dublin hotel bedrooms; the shootings of two republican prisoners in crown custody for ‘trying to escape’; the firing into a Dublin football crowd by Black and Tans with thirteen fatalities; and the savage Kilmichael ambush by Tom Barry’s flying column in west Cork which killed eighteen Auxiliary policemen, in circumstances that are still controversial. Martial law was subsequently declared in Munster, though assassinations and ‘executions’ continued unabated on both sides. But the greatest republican victory of the year was Terence MacSwiney’s death by hunger-strike in Brixton Gaol on 25 October 1920.

MacSwiney had agonized since Easter 1916 about his need to expiate the failure of Cork to rise in a sacrificial rebellion alongside Dublin, and his own irresolution in subsequently handing over Volunteers weaponry to the authorities; guilt and self-recrimination were expressed to friends and poured out in introspective poetry.31 Internment in Frongoch after the Rising had helped to rehabilitate him, as so many others inactive at Easter. He subsequently threw himself into Sinn Féin organization, was elected TD for Cork while still in gaol and entered local politics along with his companions Liam de Róiste and Tomás MacCurtain. When the latter was murdered by police in disguise, MacSwiney succeeded him as Lord Mayor of Cork, proposed by de Róiste. He was simultaneously Commandant of the IRA’s Cork No. 1 Brigade, in which capacity he horrified P. S. O’Hegarty by outlining ‘fiendish and indefensible’ assassination projects.32 Constantly cautioned and arrested, MacSwiney was heavily involved in raising finance through a Dáil loan organized by Collins; here and elsewhere his punctilio and pomposity annoyed many colleagues, including de Róiste (Collins was particularly irritated by MacSwiney’s insistence on translating every document laboriously into Irish33). Finally, the troublesome Lord Mayor was arrested in August 1920 for possession of a police cipher, refused to recognize the court and commenced a hunger-strike.

He had embraced this tactic during a previous incarceration, a tactic which was not supported by his colleagues and was strongly opposed by his wife, Muriel Murphy, whom he had married in June 1917. The wedding was the culmination of a long campaign on her part, beginning when she arranged a meeting through friends in 1915, overcoming his reluctance ‘because of the horrible imperialist family I was born into’; she pursued their relationship through her indefatigable prison-visiting.34 ‘Remember your department belongs in the next world,’ she had written prophetically to him during a manic period of sleeplessness in their early marriage; ‘I have charge of this.’35 Twelve years younger, attractive, independently well-off, strong-minded and erratic, Muriel, as well as their baby, would feature strongly in the publicity campaign which gathered momentum as MacSwiney’s hunger-strike in Brixton Gaol inexorably continued for weeks on end. But her feelings were against it, and she recorded later that she always knew it would end with his death.

All told it lasted an astonishing seventy-four days and attracted worldwide attention. MacSwiney’s status as elected Lord Mayor and member of the Dáil was emphasized for propaganda purposes, rather than his role as IRA Commandant; so were his ostentatious devoutness and commitment to self-sacrifice. He was attended throughout by priests, Sinn Féin comrades, his sisters Mary and Annie, and his wife. A parade of visitors came across the Irish Sea, including his old friend Liam de Róiste, who, in late August, was surprised to find MacSwiney still looking strong and Muriel ‘exceptionally bright and cheerful’, though ‘kept up by excitement; I think the others are a bit nervous of her. No wonder.’ De Róiste himself felt that ‘her apparent unconcern is only her way of keeping up before people; there is not the least sign of her recent “illness”.’ But he, and everyone else, was aware that MacSwiney was on a course set for death.

Meetings were held every day in Art Ó Briain’s London office, to deal with the avalanche of inquiries and the extraordinary international interest. In the intervals between giving interviews to the Dutch and Greek press and dealing with an appeal from Brazilian Catholics to the Pope, de Róiste became weary of ‘half-cracked’ people turning up to express support, expecting ‘the people in the office to be as “cracked” as themselves’.36 Colleagues such as Collins and Béaslaí privately disapproved of MacSwiney’s strategy; his sisters violently endorsed it; his wife found it difficult to support. But in this heroic martyrdom, MacSwiney found the role he had been seeking since his ambitious and frustrated youth. His laborious writings found a new audience, at an undreamt-of level; even his five-act play The Revolutionist was rapidly (and cannily) mounted by the Abbey Theatre in Dublin. ‘I think the last pages would greatly move the audience,’ Yeats judged, ‘who will see the Mayor in the [play’s] hero.’37

The martyr’s sisters would guard the sacred flame of his memory all their lives; the restive Muriel would eventually follow a more rebellious and iconoclastic path. But in the autumn of 1920 an enormous public followed his slow road to a terrible death. The Church expressed a surprisingly unequivocal degree of support, with MacSwiney receiving daily Communion and declaring that his strength was being sustained by divine intercession. He clearly saw the eleven republican hunger-strikers simultaneously engaged in Cork as his disciples, and, in a prayer which he composed on the fifty-seventh day of his strike, he offered his suffering and death to God ‘for Ireland’s resurrection’. Pleas for intervention from all sides (including the King’s private secretary) met a stony government response – possibly because Arthur Balfour, with a long record of obduracy towards Ireland, was deputizing for his coalition colleague Lloyd George. When the end came, on 25 October, the public reaction was immense: 30,000 people filed past the bier in St George’s, the Catholic cathedral in Southwark, and – for all the government’s efforts – the vast funeral in Cork claimed worldwide attention. As for MacSwiney, he was seen – like the rebels executed at Easter – to have been at last assumed into Valhalla. Father Dominic O’Connor, the priest who had attended him in Brixton Prison throughout, remarked that a new martyr had gone to join ‘Tomás [MacCurtain], Eoghan Roe [O’Sullivan], and Joan of Arc’.38 Rosamond Jacob, who had visited the MacSwiney household in Cork long before and found the siblings unsympathetic, felt torn when she listened to Min Ryan’s account of the funeral. ‘It was plainer still how she had enjoyed that. Hanna and I agreed that such things are a kind of emotional orgy. I know I am capable of such enjoyment myself and it is revolting to think of.’39

IV

Mary MacSwiney later declared that one of her brother’s last remarks to her was ‘Thank God, there will be no more compromises now.’40 By the end of 1920 the initiative seemed to have left what Collins contemptuously called ‘the forces of moderation’. Gunmen like Ernie O’Malley remembered long afterwards that, bivouacked out on the hillsides, they thought they were witnessing a new Ireland coming into being.

Gone was the country of the soft brogue or blarney, the foxhunting days and the pleasant parties or tennis tournaments. Instead was a hard, steady Ireland, cool, assertive. It had pitted its strength against the Empire and the latter was beginning to waver. The mentality of the island seemed to have changed; the political type with his flow of eloquence and his mouthings, his bland assurances, his ability to ‘pull wires’, and his gymnastic feats of conscience seemed to have disappeared. There was no room for oratory. The nation was at war . . . Simple country boys, simple in that they were not sophisticated, had found they possessed organizing and administrative ability. They had made themselves respected by their own people and, more difficult still, by those of their own class.41

But this was an idealized retrospection, written much later with knowledge of what was to come. The elections for the second Dáil in May 1921, tightly controlled by Collins and Boland, were significant. Out of 125 candidates, 47 were in gaol and 52 ‘on the run’. Several knew nothing of their candidacy till elected. The tiny remnant of the Irish Parliamentary Party abstained, as did Labour; all constituencies in the new twenty-six-county Ireland were uncontested. By contrast, every seat in the new unit of Northern Ireland was fought, returning 40 unionists, 6 nationalists and 6 Sinn Féiners (all of the last living in the South). The new Dáil represented the IRA rather than the Sinn Féin movement at large. Some sitting deputies who were not representative of O’Malley’s hard new Ireland, and felt the time had come for peace, found themselves the objects of hostility from the leadership. They included that seasoned armchair revolutionary Liam de Róiste, now less inclined towards the whole-hearted blood sacrifice which he had theoretically endorsed back in 1914. His long experience in the Cork Young Ireland Society, the Celtic Literary Society, the Cork Dramatic Society, Cumann na nGaedheal and all the rest had paved the way for a political career in the new dispensation. Re-elected as a Dáil TD, he was now an experienced Chairman and member of economic committees, as well as an Alderman of Cork Corporation, chairing its Law and Finance Committee, and a member of the Cork Harbour Board. A well-disposed English writer on a fact-finding tour in April 1921 thought him ‘a typical Republican of the Cork school . . . He too is an “intellectual” but a humorous glint behind spectacles and an occasional droop at the corners of the mouth seem to betray less sternness and a warmer humanity [than his colleague Barry Egan].’ De Róiste defended the idea of a republic to his visitor, but ‘preferred not to dogmatize about it while the matter is under consideration by the parties concerned . . . all our economic interests, all our future in fact, is bound up with you.’42 Behind the scenes, elements of the IRB leadership were similarly recognizing that the time was coming to make terms, and the British government, with Ulster removed from the equation, were already extending feelers in that direction. The ‘simple country boys’ conjured up by O’Malley, however, would be less inclined to negotiation.

With the calling of a truce in July 1921, various lines of communication were established with British politicians and civil servants. Official opinion, both in Dublin Castle and in Whitehall, had long accepted that Dominion Home Rule was the least that could be offered to nationalist Ireland – a far more viable option now that the aggressively unionist element of Ulster had been mollified. But the irredentists among the revolutionaries wanted much more, and there were already ominous signs of impending dissension. In fact, the antagonisms that would flare up into civil war six months later had long been evident. In Father O’Flanagan’s bitter words, Sinn Féin after 1917 had been built upon an uneasy compromise between hard-line republicans and moderates, ‘and the so-called Treaty [in 1921] was the wedge that burst the sections asunder.’43 The patterns of division were not always clear; de Valera’s and Collins’s respective attitudes to ending hostilities, for instance, exactly contradicted the line that each would subsequently take. While negotiations proceeded in London, back in Dublin de Valera was clearly swayed by Brugha, an extremist Anglophobe even by IRA standards, and Stack, whose administrative incompetence made him frankly long for the simplicities of open warfare. By the same token, those who eventually went to London to negotiate the Treaty with the British government were not representative of the more irreconcilable wing of the revolutionary movement.

Whether this was a deliberate decision on de Valera’s part is impossible to ascertain. But the pivotal role was played by Arthur Griffith, whose dual-monarchy ideas on Anglo-Irish relations had – a decade or so before – been so heavily criticized by radical nationalists. Since 1916 he had apparently reconstructed himself into a republican, and by 1919 his newspaper Nationality was declaring that ‘nothing short of an Independent Irish republic will satisfy the aspirations of the people of Ireland.’44 But this may have been aimed at Versailles rather than at Whitehall, and he travelled to London in late 1921 on the understanding that the time had come to treat with the enemy, and therefore compromises would have to be made. This may have been a general (if implicit) view, but Griffith took it further than many expected. By privately committing himself to Lloyd George’s seductive proposals for an oath of fidelity to the crown, and agreeing to leave the fate of Northern Ireland to a boundary commission to be assembled at some future date, he brought the rest of the Irish delegation to agree to the Treaty – which was very far from establishing ‘the republic’. The Platonic shape of that revolutionary ideal had been conjured up over the last two years by revolutionary zealots in the meeting-rooms of the Dáil and on the hillsides of Munster. In an earlier era it had been debated in student societies, over meals at the Vegetarian Restaurant, on long nights in Gaelic League summer-schools, and in the clusters of radical households at Ranelagh or on the South Circular Road. But it would remain a chimera.

Hard-headed people like Collins, anxious to get their hands on the levers of power and realistic about the limited long-term prospects of guerrilla war, felt that the dominion status offered by the Treaty would enable the eventual achievement of republican ‘freedom’. For them, in Ernest Blythe’s words, republicanism was ‘not a national principle but a political preference . . . a means to an end, not an end in itself’.45 De Valera suddenly and unpredictably repudiated this approach – though, according to General Jan Smuts, who brought his own experience as an ex-freedom-fighter to bear on the negotiations, the Sinn Féin leader had privately endorsed a dominion-style settlement the previous July. Patrick McCartan similarly recalled a conversation with de Valera just before the negotiations, when he explained he was ramping up the ‘republic’ campaign in order to make Lloyd George realize he had to take this into account. ‘In plain English he virtually said that if we talked too much republic we might not get dominion status accepted. He was in a sort of confidential mood and said that the voting would be rather interesting as the real men would be for peace and those of the Dáil who did nothing would be immutable. He believed association with the British Empire would be best for Ireland.’ As for McCartan himself, ‘I voted for the damned Treaty because I thought it was in danger – and it was, until Burgess [Cathal Brugha] made his silly attack on Collins and Griffith took advice and did not overstate his case. The longer I listened to our leaders the more I became convinced that we got much more than we deserved and that if we did not accept it England could afford to leave the rest of the fight to ourselves.’46 Internecine warfare was indeed the outcome. Almost at once the revolutionary movement began to split, and long-simmering antagonisms and resentments boiled to the surface.

The Dáil ratified the Treaty establishing the Irish Free State by seven votes in January 1922, but a large rump followed de Valera in rejecting the decision and abiding by the allegedly superior authority of the rapidly mythologized ‘second Dáil’. Power shifted from the ministers of the Dáil to the Provisional government headed by Collins and Griffith pending an election, but the constitutional position remained murky.47 An attempt was made to evade open hostilities by rigging the election under Treaty conditions, with guaranteed proportions for the two opposing sides, but Collins – who had rapidly emerged as the supremo of the new order – eventually reneged on it. Public opinion in any case was overwhelmingly in favour of the Treaty, as even its opponents gloomily admitted. This did not stop them taking up arms against it. The IRA split into two factions, and the new army of the Irish Free State under Mulcahy found itself at war with old comrades, who kept the name of ‘IRA’ and declared that their objective was ‘to guard the honour and maintain the independence of the Irish Republic’. Kevin O’Higgins, one of the most uncompromising members of the new government, referred to the dissidents more crisply as ‘a combination of degenerate Apaches’ and to de Valera as ‘a crooked Spanish bastard’. His Free State colleagues did not escape his tongue either (Collins was branded ‘a pasty-faced blasphemous fucker from Cork’).48 Mutual recrimination became the order of the day.

From the other side, young republicans such as Todd Andrews were shattered by the Treaty Debates. ‘For years I had lived on a plane of emotional idealism, believing that we were being led by great men into a new Ireland. Now I had seen these “great men” in action to find that they were mostly very average in stature, some below average, some malevolent and vicious.’49 What Mulcahy called the ‘wonderful brotherhood’ of the revolutionary Volunteers was painfully fractured. As a prominent defender of the Treaty, he himself was the target for painful attacks. ‘No matter what good things are in the Treaty, are they worth all this unhappiness, Dick?’ wrote Mary MacSwiney in a savage letter. ‘Do you not realize that we hold the Republic as a living faith – a spiritual reality stronger than any material benefits you can offer – cannot give it up. It is not we who have changed it is you.’50

When hostilities broke out between the ex-comrades in Dublin that July, with the Free State forces shelling rebel strongholds on Sackville Street while their opponents loopholed their way out of the surrounding buildings, the conditions of 1916 were re-created with a brutal irony. In another gruesome echo, assassinations on one side were met by summary executions on the other: Mulcahy deliberately used the term ‘reprisals’ in an official announcement. The violence, trauma and body-count of the Civil War, which ended in the dissidents dumping their arms in the summer of 1923, took over from the preceding hostilities against the forces of the crown. Between 1919 and 1921 about 1,500 were killed, besides the 220 fatalities of communal violence in the North; 1922–3 brought the total to more than 4,000, while the Northern toll reached 500. Arguably it burnt a deeper mark into Irish historical memory: certainly a more painful one. ‘I knew that it was the actions of the Irregular-republicans which killed idealism in my own soul; idealism that is, in connection with this country and its people,’ de Róiste recorded in his diary a year later. ‘And I know they killed it in many others as well.’51

The nature of the violence also laid bare latent divisions among the revolutionaries, and unpalatable truths about the nature of revolution, already spelt out in the intimidation, score-settling and sectarian episodes which had characterized some IRA actions during the previous campaign. Threats were made, inter alia, to exterminate ‘every male member’ of certain family connections, arousing ancient echoes of communal conflict. There was a marked exodus of frightened Protestants from some areas of the new Free State, especially during and after the Civil War. The roots of that conflict lay, on one level, in the powers claimed by people who had experienced a certain liberation from authority, while remaining conditioned by authoritarian backgrounds; their life as guerrilla comrades had given them a taste for power as well as a cavalier attitude towards democratic decisions. Less obviously, the impetus to civil war owed much to the purist hopes and dreams nurtured by Pearsean arguments for separatism. However, high-souled patriotism was not much evident in the violent and demoralizing recriminations that broke out.52 The official journal of the new Free State referred to the republican irreconcilables as ‘conscienceless, rotten and petty tyrants’ who deserved no mercy.53 The spectres of untrammelled warlordism and communal conflict were kept at a distance, especially when the contemporary upheavals in Central and Eastern Europe are borne in mind, but sometimes hovered disconcertingly near.

The more abstract issues that divided the two sides were not to do with the reality of sundered republican brethren in the north-east (whom Collins was covertly arming, before his own untimely death in an ambush by anti-Treaty forces in August 1920 – ten days after Griffith’s sudden death from a cerebral haemorrhage). Forms of words, flags and emblems, and ancient hatreds seemed to mean more, as did the idea of fealty to the crown, even in the diluted and formalized way prescribed by the Treaty. It should be remembered that the republican schoolteacher Thomas Ashe, now a canonized martyr since his death on hunger-strike, used to encourage his classes to walk over the Union Jack, and declared his own wish to urinate on it.54 For a generation preoccupied with the materialism, decadence and impurity of Englishness, salvation could be ensured only by separation. Muriel MacSwiney, appalled by the Treaty, could not bring herself to blame anyone Irish for it. She wrote, some time later (from the Pension International, Wiesbaden), to Richard Mulcahy, who had been best man at her wedding to Terence in 1917. Mulcahy, one of the Treaty’s most fervent supporters, was by now a hate-figure for irredentist republicans, but Muriel wanted to make clear that she did not blame him personally. ‘I don’t feel anything against anybody but England for what has happened . . . Although I think this treaty is by a long way the greatest infamy that the enemy has ever perpetrated on us & I will always oppose it or anything like it I feel nothing against any Irishman; the whole weight of my venom is directed against the English people . . . I shall spend my life not, as up to this, working for the complete independence of Ireland’s Republic but also working for the destruction & downfall of England & of every single English person I come across. The English people are to me now a plague of moral lepers.’55

Others, such as Máire Comerford, decided early on that those who supported the Treaty were engaged in a deliberate project of counter-revolution against the social radicalism of the ‘real’ revolution. For Liam Mellows, the Irish future was necessarily anti-materialist – echoing Pearse, who had preached in 1913 that it would be better that ‘Dublin should be laid in ruins’ than that the existing condition of contentment within the British Empire should continue. ‘We do not seek to make this country a materially great country at the expense of its honour,’ declared Mellows; ‘we would rather have this country poor and indigent, we would rather have the people of Ireland eking out a poor existence on the soil, as long as they possessed their souls, their minds, their honour.’56 This represented Gaelic League values in ruthlessly concrete form, and ‘the Irish people’ may be forgiven for not finding them universally attractive. From the other side, the ex-revolutionaries who founded the new state saw their role as necessarily ruthless in a different cause, and sometimes gloried in it. Richard Mulcahy, who had found his métier as a military organizer and would hold a number of ministerial posts in the new regime, emerged as a noted pragmatist, accepting full responsibility for the execution of ex-comrades (including Rory O’Connor and Liam Mellows) who had taken the Irregular side. More than three times as many executions were carried out by the Free State government as by the British during the previous war. Long afterwards, Mulcahy was clear in his own mind about this traumatic time. ‘The fundamental and traditional character of the people stood fast and constructive in spite of the drama, the indiscipline that drama makes up, and the chancers who are nurtured in its atmosphere, and whose operations disintegrate the natural solid foundations of a people.’57 The Free Staters represented the true values of Irishness, guarding the revolution from ‘chancers’.

Less tangible issues than life and death, still hotly debated, concerned the relationship between ‘republicanism’ and ‘democracy’; and the pursuit of the ideal by a diminishing band of idealists (or fanatics) against the overwhelming endorsement by their countrymen of a compromise Treaty that might – and did – lead to more. In some ways, the lines along which the revolution divided had been clearly anticipated by contemporary observers, and the fissure pointed up separations and tensions that had always been there. In some of the confrontations one can discern the forces of Catholic piety and social conservatism asserting themselves against the more anarchic brio of certain members of the revolutionary generation (including several women). From one angle, the Civil War pitted the ‘new men’ of the IRA, often the younger sons of farmers and those without ‘a stake in the country’, against an elite in the making who saw their time had come. Statements from Kevin O’Higgins and others in the latter camp suggest a distinct class bias; O’Higgins, like W. T. Cosgrave, represented a new, managerial and potentially conservative element within the movement. But the activities of the Irregulars were not purely grounded in disagreements over the interpretation of the Treaty. Operations also reflected the paying off of old scores, the settling of long-standing resentments, and antipathy towards people perceived as aliens, outsiders or sympathetic to British rule.58 The war was traumatic in many ways. And in several instances the separation cut through family lines and sundered old comrades and brothers-in-arms, most famously Michael Collins and Harry Boland.

Married couples were also split. Mabel and Desmond FitzGerald came near separation over his endorsement of the Treaty, she – as ever – taking a more radical line. Several women who had been married or closely related to key revolutionary leaders repudiated the Treaty in the name of the dead; they included Áine Ceannt, Mary MacSwiney, Kathleen Clarke, Margaret Pearse and Maud Gonne MacBride (as she was now generally known). For the Ryan girls, the Treaty was intensely and intimately traumatic. Min, who had married Richard Mulcahy in 1919, became with him a linchpin of the new regime – though it is a fair bet that her first love, Seán MacDermott, would not have endorsed the Treaty, had he lived to see it. Agnes and Denis McCullough also supported the Treaty and the political party – Cumann na nGaedheal, later Fine Gael – that grew out of it. But their sisters Phyllis, Chris and Nell, their brother James and above all the dominating and charismatic figure of Mary Kate set themselves firmly against it. Mary Kate and Seán T. O’Kelly would – like James – be consistent supporters of de Valera and founder members of Fianna Fáil, the ‘slightly constitutional’ party which he founded in 1926 on the basis of opposing the Treaty, and which propelled him to supreme political power in Ireland for decades from the early 1930s. The rift between Seán T and Denis McCullough, his closest friend as well as his brother-in-law, was particularly searing.59 Phyllis at one point instructed Min – unsuccessfully – to leave her husband over his support of the Free State. The Ryan family and their spouses tried to preserve some vestiges of that powerful bond, forged in the heady days of student radicalism before the war, and during the astonishing years of the revolution; there were gatherings at the farm at Tomcoole in the summer, where the children holidayed with their cousins and politics were not spoken of. But the wounds went deep, and Phyllis did not speak to her pro-Treaty siblings for some years. Many of those brought together in the fervour of their youth must have silently echoed the words of the anti-Treaty IRA leader Liam Lynch, dying after a shootout with Free State forces in the Knockmealdown Mountains on 10 April 1923: ‘It should never have happened.’60

As the dust settled and the new Free State came into being, with it came an inheritance of antagonism and the creation of a new political class. From his vantage as a recently appointed Senator, W. B. Yeats observed the ministers of the new government:

They had destroyed a system of election and established another, made terrible decisions, the ablest had signed the death-warrant of his dearest friend. They seemed men of skill and mother-wit, men who had survived hatred. But their minds knew no play that my mind could play at; I felt that I could never know them. One of the most notable said he had long wanted to meet me. We met, but my conversation shocked and embarrassed him . . . Yet their descendants, if they grow rich enough for the travel and leisure that make a finished man, will constitute our ruling class, and date their origin from the Post Office as American families date theirs from the Mayflower.61

Even among these victors, there were powerful dislikes and ancient feuds. After the sudden deaths of Collins and Griffith in 1922, the successor strong-men of the regime were W. T. Cosgrave and Kevin O’Higgins, who were not representative figures from the pre-revolutionary era; O’Higgins himself admitted to his fiancée that he ‘had no pre-’16 record – the little good that’s in [me] dates from that’. In fact his family background was that of the old Parliamentary elite, since, being a nephew of T. M. Healy, he was closely related to the powerful O’Sullivan nexus from Cork. He was also the son of a local JP, had been educated at Clongowes, and had spent a frivolous UCD career as a lackadaisical law student. Cosgrave also came from the solid and moneyed Catholic middle class, and emerged into politics through the Volunteers and the reconstructed Sinn Féin of 1917. Such men represented a new wave of activists, detached from the visionary republicanism and cultural excitements of the pre-revolutionary era. Michael Hayes, who had been formed in that older tradition, noted that O’Higgins ‘didn’t understand to the same extent what [the revolution] was all about . . . he reduced it to the notion of the Irish people getting a parliament.’62 To some, this looked uncomfortably close to Home Rule.

When this is taken with the fact that by the time of his death by assassination in 1927 O’Higgins was privately preoccupied by the project of a reunited Ireland coming back under a dual-monarchy, it can be seen why some of the disgruntled revolutionaries saw the ghosts of the Irish Parliamentary Party all around them. Hayes’s friend Mulcahy, though serving (rather uncomfortably) in office alongside O’Higgins and Cosgrave, looked back to that pre-revolutionary era too, and retained a fidelity to the old IRB. (The punctilious Mulcahy was equally uncomfortable with the freewheeling approach of Collins’s ex-squadristi, still influential in the upper echelons of the Free State Army, and his suspicions would be vindicated when they threatened a mutiny in 1924.) But the more influential figures in the new Free State were sceptical about much that had gone before, in the carefree days before 1916. Their priority was to build a new regime that would be stable, conservative and fiscally solvent. Given the challenge of the Civil War, with the Irregulars ordering the assassination of pro-Treaty ministers, TDs and even newspaper editors on sight, a ruthless pragmatism was understandable. But it also announced an end to the dreams of a new Ireland nurtured by many of their older colleagues.