EVERYONE AROUND ME screamed. A few days before Christmas 1973, my mother, Jean-Pierre, and I were on our way from Lima to Huancayo, a medium-sized city in Peru’s central highlands. Our overstuffed train was winding along the highest tracks in the world, hugging the side of a mountain on the western slopes of the Andes, when it hit a boulder. It jumped the tracks, stuttered wildly, and then came to a screeching halt, barely avoiding a long, disastrous tumble down the mountain.

In those terrifying seconds after the impact, all my eight-year-old brain could think of was the order of French fries I had just placed. I screeched, “Ay caramba, mis papas fritas!” and our whole car burst into laughter.

During the chilly hours that we patiently waited by the side of the tracks for another train to come, my mother and I struck up a conversation with Angelica, a teenage girl with thick, long, braided black hair. She was maybe sixteen, and said she came from Jauja, the first capital of Spanish Peru and the cultural capital of the central highlands. A small town of mostly Indian inhabitants, it was only a short bus ride from Huancayo, and Angelica made us promise to visit her and her family.

Now that her Spanish was passable, my mother’s plan was to try to get a job teaching sociology at the Universidad Nacional del Centro in Huancayo once the semester started in April. That way, she hoped, she could embed herself in the community and get involved in local political struggles. But that was still months away, and so we decided to visit Jauja. Before boarding the bus we shopped at Huancayo’s Sunday market. My mother bought me a beautiful white, brown, and black alpaca sweater, and Jean-Pierre bought me a wood flute and a little pouch as a good-bye gift. He would be returning to Lima. My mother had lost interest in him, perhaps because he was ultimately more into taking photos than talking politics. I would miss Jean-Pierre and his fancy Nikon, especially since we didn’t have a camera of our own, though I would not miss having him in the room with my mother and me at night.

Once again I had my mother all to myself, at least for the time being. Things were less complicated when it was only the two of us. She didn’t ask me what I thought about Jean-Pierre or his leaving—she never asked me about any of the boyfriends who came and went—but maybe she could sense that I liked it best when we were taking care of each other on our own.

In Jauja, nestled in Peru’s Mantaro Valley almost two miles above sea level, all the buildings wore red-tile roofs and most were made of adobe. Only part of the town had electricity, and even there the current was unstable. Banners in the streets decried the electricity problem. Cultivated hills, some dotted with crumbling Inca ruins, surrounded the town.

We checked into a small hotel close to the town plaza and were given a narrow room with one small bed. The hotel had no heat or hot water, but our room was clean and cheap. It was the day before Christmas. I spent hours playing soccer in front of the hotel with other neighborhood kids, and at night lit firecrackers with the hotel owner’s son. Most of the kids were friendly enough, except for the bully who teased me and called me gringa because of my long hair. My mother was still refusing to let me cut it.

On Christmas Day, drunken men, young and old, were dancing in the streets. They reminded me of Rosa’s husband, Mauricio, back on the farm in Chile. I hoped he and Rosa and the family were safe. And I couldn’t help thinking of my own, assuredly sober father, so far away, who was no doubt having a very different kind of Christmas celebration. I imagined he would want me there with him, acting out his dream of the happy family.

Angelica’s home turned out to be only a few blocks from our hotel, above a little restaurant her family owned on Junin Street. There were only maybe half a dozen small tables, and the mostly male customers seemed to come to drink Pilsen as much as to order food. My mother and I introduced ourselves to her family the day after Christmas and then came back every day thereafter. We ate all our meals there, usually the daily soup with garlic, potatoes, and rice. There was no menu; one simply ate whatever Angelica’s mother, Emma, cooked that day.

I quickly became friends with Angelica and enjoyed hanging out at the restaurant. A week later, my mother and I moved in with Angelica’s family; it was cheaper than staying at the hotel, and they had plenty of room for us. Hildo, Angelica’s older brother, had just left to join the army, so we rented his room, its large windows looking over neighboring rooftops. Pigs, chickens, and rabbits lived in the muddy backyard. We had a table and an electric lamp, so my mother had a place to write in her diary or type away on her little manual Olivetti. My mother paid the family seven hundred soles a week for room and board. We still had some of the savings she had brought with us from Berkeley over a year earlier, but we were apparently close to broke, though she never shared her money concerns with me.

While we lived with Angelica and her family, my mother tried to work with me on my reading and writing, but I stubbornly resisted and was easily distracted by all of the people coming and going from the restaurant. I joined the neighborhood kids in water-balloon fights on the streets, trips to the outdoor market, and of course kicking a soccer ball around. I learned to pester foreign tourists, hoping to earn some spare change; I would offer to translate for them when bartering with vendors. Jauja became my playground, a world with no real rules or parental oversight. As my mother jotted down in one of her diary entries from January of 1974, “Peter drove by in a truck with a bunch of strangers. What’s he up to?! Wonder if we’re going to a party tonight?”

As I made friends across town, though, my focus was always on Angelica. I missed Pedro on the farm in Chile, but in Jauja, Angelica was my world. I was devoted to her, despite the fact that she had a boyfriend, Daniel. She, in turn, was happy to play big sister, something I’d never had. Angelica adored me and I adored her. She saved some of her most radiant smiles for me. She took me everywhere with her and had more luck than my mother did getting me to work on reading and writing lessons.

Angelica even managed to cure me of sarna. I had not been able to stop itching. My mother called it “the itch” because at first we had no idea what it was. I had blisters, redness, and intense itching on my fingers, with the webbed areas between my fingers oozing a clear pus. Turns out I had become a breeding ground for tiny mites. The local doctor told us I had something called sarna and gave us a white powder to put on it. We looked up sarna in our Spanish-English dictionary: scabies, otherwise known as mange. It was contagious, but my mother somehow managed not to get it from me. The mites were completely attached to me as their host. I was miserable. We tried new lotions and soaps. “The itch” still wouldn’t go away. Then Angelica rubbed chili peppers into the soft skin between my fingers. That did the trick, and I was finally cured.

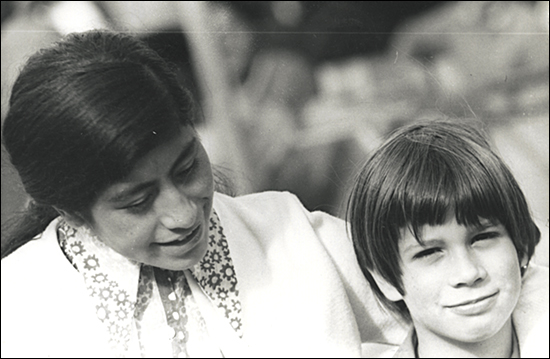

With Angelica in Jauja, January 1974

Angelica always took me with her to the movies on the weekend, but that was mostly an excuse to meet up with Daniel. There was only one movie theater in town, on the corner of the town’s central plaza, and there was little logic to what it played—an old Western, a kung fu flick, a sappy romance. I didn’t care. When Angelica was grounded for sneaking out to see Daniel, I chose to stay home with her and skip the shows. When Daniel tried to visit Angelica, her father kicked him and screamed at him and chased him away from the house. He didn’t want any man near his daughter. Daniel, tall, muscular, and handsome, was twice the size of Angelica’s pudgy and potbellied middle-aged father, but he always respectfully backed off. Sometimes Angelica gave me a love note to secretly pass on to Daniel, and it made me feel important that she trusted me to be their accomplice. I’d smuggle the note out the front door past Angelica’s oblivious father, dart around the corner and hand it to Daniel waiting a block away, and then bring a note back to Angelica, who would give me a warm thank-you kiss on my forehead before disappearing to her room to read it. When she then reappeared with a new note, I’d slip back off to Daniel. Angelica’s father never caught on.

One afternoon, Angelica took me to the church and cemetery for a funeral. When I came back, I ran to my mother, promising her that when she died I would keep fresh flowers on her grave. “Mommy, you should have seen all those graves with all those flowers. You like flowers, so I’ll make sure to put flowers on your grave, too.”

My mother paused, startled. “Oh, Peter, I appreciate the sentiment, but hopefully that won’t be for a while yet. Besides, I want my body to be cremated—you know, burned to ashes—so I won’t need to have a grave at all.”

“But then where will I put the flowers?” I asked, disappointed.

My mother laughed. “Let’s not worry about that right now. But in the meantime you can give me flowers whenever you want.”

Ever since my mother was missing for those weeks after the military coup in Chile, I’d been worried that she was going to get herself killed. “Sometimes you have to die for a good cause,” my mother had said to me when explaining Allende’s death, which didn’t help. Seeing my alarm, she continued: “Oh, don’t worry, I’m not going to die like Allende anytime soon. It’s possible, I suppose, but I’m not planning on it.” Perhaps she never realized how terrified I was that she would suffer a violent death, but this was just one more example of her parenting philosophy. My mother never really treated me or spoke to me like a child. I liked that equality, that responsibility, that respect, even as I craved reassurance. And we did take care of each other, especially when sick, though she got sick a lot more than I did. One Jauja diary entry read, “Sick in bed today with diarrhea like I’ve never had before. . . . Peter is bringing me things I need and even dumped my shit pan, with a hanky tied to his nose.”

By the middle of January, the town was gearing up for the annual Tunantada festival, when they celebrated the patron saints San Sebastián and San Fabian. Caught up in the excitement, my mother and I watched as the crowds gathered. Prominent men from the community, called chutos, began to clear the streets of people to make way for the bands. The chutos wore small rounded black hats with brightly colored cloth strips around the base, white shirts with matching scarves, elaborately embroidered vests, and knee-length pants. But most distinctive were their painted masks of animal skin and fur. I was captivated by their masked faces. The chutos were not smiling; they never smiled. There was something solemn and serious about them even as they danced about. They danced in high leather boots, almost bouncing along the ground, for hours, only stopping for the occasional drink of chicha or beer at one of the many street stalls set up for the occasion.

Among those who joined the festivities were dozens of men dressed in elegant dark-colored Spanish-colonial costumes, wearing masks of paper with painted-blue eyes. Half were dressed up as women. At first this confused me—I thought they really were women and didn’t entirely believe my mother when she insisted they were actually men. How weird, I thought, that men would impersonate women. When I asked her why these were not real women, she explained that women were not allowed and that this showed how sexist the society was.