|  |

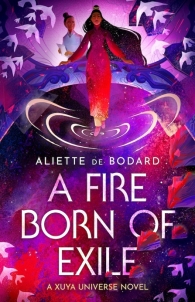

Aliette de Bodard

(Gollancz, 2023)

Reviewed by Nick Hubble

THERE IS A SELECT TRADITION of SF novels drawing inspiration from The Count of Monte Christo by Alexandre Dumas, which includes Alfred Bester’s The Stars My Destination and Gwyneth Jones’s Spirit, or the Princess of Bois Dormant. To these may now be added Aliette de Bodard’s A Fire Born of Exile, a subtle combination of the original revenge plot with engineering problems and sapphic romance. The novel, like its Clarke-shortlisted predecessor The Red Scholar’s Wake, is set in the Xuya universe; specifically in the Scattered Pearls Belt, a remote string of habitats remaining under tight military control following an unsuccessful revolution ten years previously. This self-contained society is disrupted by the appearance of a mysterious stranger, a woman of indeterminate age with jet-black hair and a way of carrying herself ‘as though the entire world was an egg that needed to be broken open to release the hatchling within’. Hiding her family and lineage by describing herself with the literary name of the Alchemist of Streams and Hills, it quickly becomes clear that Quýnh has both many talents and a hidden past.

We first encounter her when she saves Minh, the daughter of the ruling Prefect, from a kidnap attempt. But the character whose life Quýnh most impacts is Hoà, who runs a bot repair shop with her younger sister, Thiên Dung.

Hoà makes regular visits to the grave of her older sister, Thiên Hanh, who was killed by a mob due to her association with her student, Dã Lan, who had herself been executed for her involvement in the revolution. On one of these visits, she encounters Quýnh paying respects at her sister’s grave, which swiftly leads to friendship and more. Hoà has also been employed by Minh and her friend, the mindship Heart’s Sorrow, to repair another older mindship, Flowers at the Gates of the Lords, who is floating damaged in space. As the novel progresses, the fates of these characters are drawn closer together and become increasingly intertwined with the apparent corruption of the mothers of Minh and Heart’s Sorrow, respectively the Prefect, Đức, and the military commander, General Tuyết, as Quýnh’s revenge plot tightens relentlessly. The tension in the novel is further heightened by both the slow disclosure of what actually happened in the past and the more immediate drama of whether either or both Minh or Hoà will be sacrificed to Quýnh’s quest for vengeance. Indeed, Hoà realises Quýnh’s nature at their very first meeting, telling her, ‘You’re a shark, a tiger, and we’re just rice fish’, but this doesn’t lessen the attraction she feels, nor indeed that felt by the reader. All of which makes for an intricate and very satisfying romance, in the broader sense of the term.

It is interesting to see Gollancz use the current buzzword ‘heartwarming’ to describe the novel amongst all the other keywords that de Bodard’s capacity to interweave complex themes and plot strands requires them to name check: love, revenge, power, corruption. It’s not an inappropriate term—enjoyers of romance, such as myself, who expect a satisfying resolution will not be disappointed—but it does perhaps slightly undersell both the political force and the literary sophistication of this complex and nuanced work. In common with Ann Leckie (also referenced by the marketing team in time-honoured ‘perfect for the fans of’ style), what characterises de Bodard’s work is not just the mastery of mannered exchanges underpinned by steely edges, but also her ability to use genre forms to demonstrate the possibility of progressive social change. In particular, drawing on her own work background, de Bodard is adept at integrating engineering concerns into human relationships; she writes about people as the cyborgs we are, effectively co-dependent on technology. As a consequence, she is able to portray a twenty-first century morality not rooted in traditional precepts or universal judgements, but something more malleable and nuanced, drawing on our changing understanding of identity. In A Fire Born of Exile, hope for a better future is not related to a specific political or social structure—the revolution, after all, has failed—but to the possibility of living individual lives in good faith in relation to a culture of consent, which is not characterised by choice theft. While that is a genuinely heart-warming prospect, it also holds out the possibility of something more: a new sensibility and way of living that is a radical step beyond the way things have hitherto been.