|  |

Matthew Holness

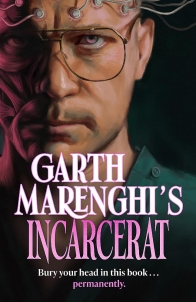

(Coronet, October 2023)

Review by Donna Scott

FOLLOWING ON FROM the success of the first TerrorTome book, both in print and for its theatrical run, Garth Marenghi is back with Incarcerat, the second volume. Marenghi made up that titular word, which he is keen for you to know so you’ll think he’s like Shakespeare, contributing to the expansion of the English language, rather than just not bothering to look up the proper word in the dictionary.

We are in familiar format territory to TerrorTome as Holness’s alter-ego has brought back the same protagonist, Nick Steen, along with his long-suffering editor, Roz Bloom, who must deal with all the dreadful things that Steen’s imagination has wrought upon the world, but mainly upon his hometown of Stalkford. This time there is also a map of Stalkford to demonstrate how Nick’s brainleak from the previous book has affected the environment. It is a thing of joyous hilarity, replete with all the horror tropes you would expect, such as wyrms, deconsecrated churches, scary science corporations, haunted houses, unclassified roads, and nearby restaurants.

Just as with the first book, Incarcerat is broadly divided into three intertwining stories: the lead story “Incarcerat”, which provides the narrative framework for the rest of the book, plus “Arabella Mathers”, and “Randyman”. On this occasion, each story involves Marenghi’s attempts at exploring different aspects of horror via his protagonist Steen, layering bad writer characters within bad writer characters once again.

“Incarcerat” is a mishmash of Final Destination meets Horror Hospital. Nick Steen has become a part-time pilot, deliberately crashing planes to be the sole survivor, much like one of his own horror novel protagonists, in a strange and frankly inexplicable attempt to rid himself of the curse of his psychic abilities. He must be stopped! The only thing that can deter his course of action is to be kidnapped, lured under the pretext of going to accept a literary award to the mysterious Nulltec Corporation who imprison him, making him the “incarcerat”. Can Steen be persuaded to develop his psychic abilities, so they work, and then use them for good, and rescue a plane with his editor in it? As you can imagine, Steen is torn by this dilemma. The relationship between writers and their editors is ripe for literary in-jokes.

In “Arabella Mathers”, editor Roz unearths a manuscript written by Steen in which his protagonist Nicholas Stein is a horror writer who goes with his daughter Gwendolyn to stay in a creepy house once owned by another writer, the obscure master of gothic horror, Anton Mathers, who lived there with his daughter Arabella. The superstitious villagers present Stein with a doll, which of course is possessed by Arabella. Can Stein escape the haunted mansion, and will he remember to take his daughter with him? There are clear nods to The Conjuring series of films, as well as elements of folk horror.

“Randyman” is a reworking of the Clive Barker story, “The Forbidden”, which has been made into numerous films entitled Candyman. The toilet wall graffiti that tells of the Randyman brings to life the murdered and vengeful toilet attendant Randy Streak, yet another character from Steen’s depraved oeuvre, depicted as a stereotypical pervert in dirty mac and trilby. This time editor Roz must appeal to the foul creation, telling him she was the one to suggest providing him with a sympathetic backstory. This would seem to be a dig at the way in which villains can be redefined as misunderstood in films such as Joker.

Unfortunately, this time I was unable to catch the live show, in which Holness, as Marenghi, keeps in character throughout a hilarious reading and Q&A as the pompous, surly, and just plain bad writer, Garth Marenghi. I had mentioned in my review of TerrorTome, just how much seeing the show had added an extra dimension of hilarity and increased my enjoyment of the book. Certainly, I think a performed reading, or audio version of this book, too, may increase the impact of some of the jokes. For example, when author Nick Steen thinks the words “Randyman” in his head, they become the chant that calls forth the dream demon. In the film Candyman, of course, the victims were compelled to say that name three times to conjure him. But as the Randyman has come from Steen’s powerful literary imagination, the required chant equals the number of Randyman books he has written, i.e. seventeen. The eyes can skim over the word “Randyman” written seventeen times and not notice the ridiculousness, whereas if you were waiting for a character to get to the end of such a chant, that’s very funny indeed.

Much of the humour in Incarcerat comes from laughing at the bad writer, but Holness has recognised that although TerrorTome had a winning formula, an exact carbon copy might prove dull. We have the bad writing, the digs at editors and writers alike, the silly footnotes, and the ludicrous layering of characters written by a character written by a character written by a character written by Holness. Marenghi’s horror is grotesque, puerile, and absurd, and Holness knows exactly what he is doing. This is very funny indeed.